China Arts & Entertainment

Kawaii Dolls & Digital Tools: How The Forbidden City Caters to Modern Audiences

The century-old Forbidden City is finding new ways to cater to younger, tech-savvy audiences. From its online ‘kawaii’ dolls to interactive apps, Beijing’s Palace Museum is using e-commerce and digital tools to keep up with China’s fast-moving trends while preserving its traditional culture.

Published

9 years agoon

By

Diandian Guo

The century-old Forbidden City is finding new ways to cater to younger, tech-savvy audiences. From its online ‘kawaii’ dolls to interactive apps, Beijing’s Palace Museum is using e-commerce and digital tools to keep up with China’s fast-moving trends while preserving its traditional culture.

Over the recent years, the 6 century-old Forbidden City, that houses the Palace Museum, has started to make the traditional trendy again by focusing on e-commerce, creative design, and tech tools.

The Forbidden City, the former Chinese imperial palace in the center of Beijing, was constructed from 1402 to 1420. It was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987 for its grand architecture and embodiment of traditional Chinese culture.

In the modern age of internet and technology, the Forbidden City faces the same challenges as many museums around the world: how to close the gap between the distant history and tradition of the museum, and the modern, tech-savvy people visiting it?

The Forbidden City’s answer to this challenge lies in its use of digital tools and creative products. Especially the Forbidden City museum products, promoted on Chinese e-commerce platform Taobao or Apple’s app store, have become popular amongst a younger audience.

The core idea of these creative products is to “root in traditional culture and bind with popular culture”. By the end of 2015, the Forbidden City had already developed over 8600 different trendy products.

‘Taobao Forbidden City’

In 2010, the Palace museum opened an online shop on China’s biggest e-commerce site Taobao. Called Taobao Forbidden City (故宫淘宝), the e-commerce shop goes beyond the traditional museum souvenir shop and offers a wide variety of innovative products. The online museum shop annually sells thousands of items and is given a good rating by 99.51% of the buyers.

Key to the success of the online museum shop is how it combines popular design and modern functionality in its products.

One of the most popular items of the shop is the Forbidden City Doll (故宫娃娃). The dolls represent Chinese historical figures, with a ‘kawaii’ design. This concept of ‘cuteness’ comes from Japanese pop culture and has also become popular in China.

With big round heads, chubby rosy cheeks and small beady eyes, these dolls are supposed to typify former residents of the Forbidden City during the Qing Dynasty. They are emperors, empresses , guards, officers and soldiers – wearing the traditional clothing of their time.

Dolls sold at the Taobao Forbidden City e-shop.

Apart from just being decorative, the cute figures also have useful functions. They can, for example, serve as phone holders or picture clippers.

The items sold on the Palace Museum’s Taobao shop are all daily products with a touch of Chinese traditional culture. Other popular items sold at the online museum shop include stationary tape decorated with emperor Qian Long’s handwriting or historical figure keychains.

The shop also plays around with the concept of Chinese online memes by photoshopping traditional paintings, such as that of Emperor Yongzheng, making these historical figures smile or adding popular hand gestures (see image below of the Taobao shop of the Forbidden City).

Besides selling creative products on their online shop, the Forbidden City is also going digital in other ways.

Forbidden City on the App Store

The Forbidden City (aka Palace Museum) has launched a series of apps on the on the Apple App Store since 2013. Some of these apps digitize the museum’s collections.

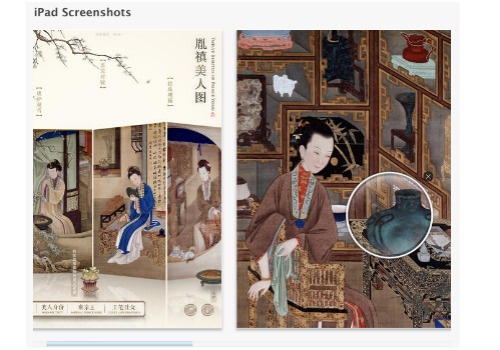

The Twelve Beauties App, the first app developed by the museum’s app development team, revolves around the screen painting set ‘The Twelve Beauties’ by Emperor Yongzheng, so that users can view them in detail on their mobile devices. The app received recognition as an outstanding app by “App Store 2013”.

Image: from the Forbidden City app Twelve Beauties by Emperor Yongzheng.

A newer app, the Palace Museum Ceramic App (故宫陶瓷馆), allows users to see the museum’s ceramic vase collection from their iPhone or iPad. The 2016 app ‘Everyday Palace’ (每日故宫) highlights a different item from the museum collection every day and explains its history and details to the app users.

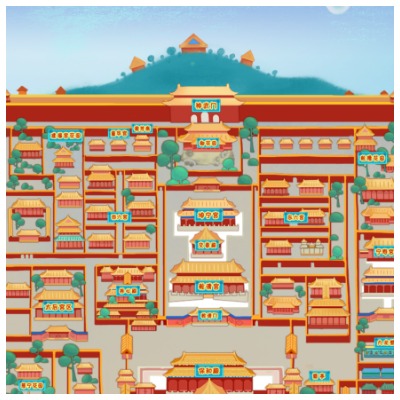

The Palace Museum official apps have generally been well received, with average App Store ratings between 4.5 and 5 stars. Especially the app developed for children receives high ratings. In ‘One Day in the Life of an Emperor’ (皇帝的一天), children learn all about the Forbidden City by playing various games around the digitalized city.

Users can play games while learning about the Palace Museum in this app.

The Forbidden City also uses technology in another way to enhance visitor experience – also for those who cannot come to the actual museum.

As early as 2003, it published its first virtual reality DVD, titled “Forbidden City: Palace of the Son of Heaven (紫禁城-天子的宫殿)”, that allowed people to virtually explore the Taihe Palace (太和殿), the very first palace at the entrance of Forbidden city, from every perspective.

This September, the Forbidden City and Fenghuang TV signed a strategic contract to use augmented reality (AR) in presenting its collections. AR technology makes it possible for audiences to experience artworks multidimensionally. It can, for example, bring paintings to life via a smartphone camera, or it can show 3D holograms that can answer questions from visitors to make museums more interactive.

One important project incorporated in the contract is a lively presentation of Along the River During the Qingming Festival (清明上河图), a 5-metre long painting that depicts urban life in the capital of North Song Dynasty (960-1127).

600-Year-Old ‘Grandpa’ Catches up with Time

The attempts of the 600-year-old Forbidden City to catch up with time seems to be paying off. According to Xinhuanet, the museum’s creative products earned a staggering 1 billion RMB (±150 M US$) revenue for the Palace Museum in 2015.

Chinese netizens seem to appreciate the efforts of the Palace Museum to become more modern. A much talked-about topic on Chinese social media, the Palace Museum has become a new “internet celebrity” (网红 – an online hit). Under Taobao Forbidden City’s Sina Weibo account, netizens lovingly address the Forbidden City with the cute nickname “gong gong” (from Chinese word “宫”, gong, meaning palace).The official Weibo account of the Palace Museum now has over 2.1 million followers (@故宫博物院).

The Palace Museum is not the only museum or historical tourist site that is exploring new technologies to promote its collection and appeal to modern audiences. The Longquan Temple (龙泉寺) in Beijing, for example, made headlines earlier this year with the launch of its robot monk Xian’er, a chubby boy monk that can answer questions about Buddhism to tourists who visit the temple.

Through its recent uses of digital tools and trendy design, the Forbidden City is transforming its distant and serious image to one that is more approachable and new-fashioned.

“Now I feel like I really know the Forbidden City”, one netizen writes.

-By Diandian Guo, edited by Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Diandian Guo is a China-born Master student of transdisciplinary and global society, politics & culture at the University of Groningen with a special interest for new media in China. She has a BA in International Relations from Beijing Foreign Language University, and is specialized in China's cultural memory.

China Arts & Entertainment

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

From China’s first soap opera Yearnings to the rise of AI-fueled nostalgia.

Published

3 days agoon

July 2, 2025

The year is 1990, and the streets of Beijing’s Fangshan District are eerily quiet. You can almost hear a pin drop in the petrochemical town, as tens of thousands of workers and their families huddle around their televisions, all tuned to the same channel for something groundbreaking: China’s very first soap opera, Yearnings (渴望 Kěwàng).

Yearnings tells the story of Liu Huifang (刘慧芳), a female factory worker from a traditional working-class family in Beijing, and her unlikely marriage to university graduate Wang Husheng (王沪生), who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Liu finds an abandoned baby girl, she adopts her and raises her as her own, against her husband’s wishes.

The couple is unaware that the foundling is actually the illegitimate child of Wang’s snobbish sister, Yaru. After Liu and Wang have a biological son, the marriage comes under further pressure, eventually leading to divorce. Liu is left as a single mother, raising two children on her own.

Still from Yearnings, via OurChinaStory.

Drawing inspiration from foreign dubbed television shows, Yearnings was produced as China’s first truly domestic, long-form indoor television drama. Spanning 50 episodes, the series traces a timeline from the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s through to the late 1980s—one of the most turbulent periods in modern Chinese history.

Before the series aired nationally on CCTV and achieved record viewership, the first station to air Yearnings in the Beijing region was the Yanshan Petrochemical TV Station (燕山石化电视台), China’s first major factory TV station (厂办电视台) located in Fangshan District.

Here, in this town of over 100,000, Yearnings garnered an astonishing and unprecedented 98% audience share. The series was truly groundbreaking and became a national sensation—not just because it was China’s first long-form television drama, or because it was a locally produced drama that challenged the long-standing monopoly of state broadcaster CCTV, but because Yearnings marked a major shift in television storytelling.

Until then, Chinese TV stories had always revolved around communist propaganda, or featured great heroes of the revolution. Yearnings, on the other hand, was devoid of political content and focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary people and their everyday struggles—love, desire, marital tension, single motherhood—topics that had never before been so openly portrayed on Chinese television.

The show’s creators had perfectly tapped into what was changing: the Communist Party was slowly withdrawing from private life, and people were beginning to see themselves less defined by their work unit and more by their home life—as consumers, as partners and parents, as citizens of a new China filled with aspirations for the future. Yearnings’ storyline was a reflection of that.

Chinese-Style “Nostalgia Core”

Yearnings marked a cultural turning point, coinciding with the rapid spread of TV sets in Chinese households. In 1992, economic reforms triggered a new era in which Chinese media became increasingly commercialized and thriving, before the arrival of the internet, social media, and AI tools once again changed everything.

Today, Yearnings still is a topic that often comes up in Chinese online media. On apps like Douyin, old scenes from Yearnings are reposted and receive thousands of shares.

📌 It’s emblematic of a broader trend in which more netizens are turning to “nostalgia-core.” In Chinese, this trend is known as “中式梦核” (Zhōngshì Mènghé), which literally means “Chinese-style dreamcore.”

Dreamcore is an internet aesthetic and visual style—popular in online communities like Tumblr and Reddit—that blends elements of nostalgia, surrealism, and subconscious imagery. Mixing retro images with fantasy, it evokes a sense of familiarity, yet often feels unsettling and deserted.

The Chinese-style dreamcore (中式梦核), which has become increasingly popular on platforms like Bilibili since 2023-2024, is different from its Western counterpart in how it incorporates distinctly Chinese elements and specifically evokes the childhood experiences of the millennial generation. Content tagged as “Chinese-style dreamcore” on Chinese social media is often also labeled with terms like “nostalgia” (怀旧), “childhood memories” (童年回忆), “when we were little” (小时候), and “Millennial Dream” (千禧梦).

According to the blogging account Yatong Local Life Observer (娅桐本地生活观察), the focus on the millennial childhood can be explained because the formative years of this generation coincided with a decade of rapid social change in China —leaving little in today’s modern cities that still evokes that era.

🌀 Of course, millennials in the West also frequently look back at their childhood and teenage years, particularly the 1980s and 1990s—a trend also embraced by Gen Z, who romanticize these years through media and fashion. In China, however, Gen Z is at the forefront of the “nostalgia-core” trend, reflecting on the 1990s and early 2000s as a distant, almost dreamlike past. This sense of distance is heightened by China’s staggering pace of transformation, modernization, and digitalization over the past decades, which has made even the recent past feel remote and irretrievable.

🌀 Another factor contributing to the trend is that China’s younger generations are caught in a rat race of academic and professional competition, often feeling overwhelmed by the fast pace of life and the weight of societal expectations. In this high-pressure environment—captured by the concept of “involution” (内卷)—young people develop various coping mechanisms, and digital escapism, including nostalgia-core, is one of them. It’s like a cyber-utopia (赛博乌托邦).

🌀 Due to the rise of AI tools available to the general public, Chinese-style nostalgia core has hit the mainstream because it’s now possible for all social media users to create their own nostalgic videos and images—bringing back the 1990s and early 2000s through AI-generated tools, either by making real videos appear more nostalgic or by creating entirely fictional videos or images that recreate scenes from those days.

So what are we seeing? There are images and videos of stickers kids used to love, visuals showing old classrooms, furniture, and children playing outside, accompanied by captions such as “we’re already so far apart from our childhood years” (example).

Images displayed in Chinese Dreamcore.

And notably, there are videos and images showing family and friends gathering around those old big TVs as a cultural, ritualized activity (see some examples here).

Stills from ‘nostalgia core’ videos.

These kinds of AI-generated videos depict a pre-mobile-era family life, where families and communities would gather around the TV—both inside and outside—from classrooms to family homes. The wind blows through the windows, neighbors crack sunflower seeds, and children play on the ground. Ironically, it’s AI that is bringing back the memories of a society that was not yet digitalized.

Nowadays, with dozens of short video apps, streaming platforms, and livestream culture fully mainstream in China—and AI algorithms personalizing feeds to the extreme—it sometimes feels like everyone’s on a different channel, quite literally.

In times like these, people long for an era when life seemed less complicated—when, instead of everyone staring at their own screens, families and neighbors gathered around one screen together.

There’s not just irony in the fact that it took AI for netizens to visualize their longing for a bygone era; there’s also a deeper irony in how Yearnings once represented a time when people were looking forward to the future—only to find that the future is now looking back, yearning for the days of Yearnings.

It seems we’re always looking back, reminiscing about the years behind us with a touch of nostalgia. We’re more digitalized than ever, yet somehow less connected. We yearn for a time when everyone was watching the same screen, at the same time, together, just like in 1990. Perhaps it’s time for another Yearnings.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Sources (other sources included in hyperlinks)

Koetse, Manya. 2016. “From Woman Warrior to Good Wife – Confucian Influences on the Portrayal of Women in China’s Television Drama.” In Stefania Travagnin (ed), Religion and Media in China. New York: Routledge.

Rofel, Lisa B. 1994. Yearnings: Televisual Love and Melodramatic Politics in Contemporary China. American Ethnologist 21(4):700-722.

Wang, Dan (汪丹). 2018. “《渴望》的艺术价值” [The Artistic Value of Yearnings].” Originally published in Beijing Daily (北京日报), October 12, 2018. Reprinted in Digest News (文摘报), October 20, 06 edition. Also see Sohu: 当年红遍大江南北的《渴望》.

Wang Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, a Chinese television soap opera with a message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Zhuge Kanwu. 2021. “重温1990《渴望》:苦得“刘慧芳”希望被导演写“死” [Revisiting 1990’s Yearnings: The Suffering Liu Huifang Hoped to Be Written Off by the Director]. Zhuge Dushu Wu (诸葛读书屋), January 22. https://wapbaike.baidu.com/tashuo/browse/content?id=b699ee532cf79f862bfa14ad.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Celebs

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Published

1 week agoon

June 27, 2025

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China this week. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Chinese beauty influencer and livestreamer Du Meizhu (都美竹) is facing online backlash this week after a former female fan filed a police report accusing her of scamming her out of nearly 200,000 yuan (approx. US$27,800).

The fan, known online as Sister Bing (Weibo handle @冰点人a冰点), has come forward with detailed allegations, claiming Du began swindling her in 2022.

Du Meizhu rose to national prominence in 2021 when she was 19 years old and became the first person to publicly accuse Chinese-Canadian pop star Kris Wu (吴亦凡) of rape and sexual misconduct. After at least 24 more victims also came forward, Wu was formally arrested on suspicion of rape in mid-August 2021 and was later sentenced to 13 years in prison.

It was around this time that ‘Sister Bing,’ whose real name is Ms. Zhu (朱, born 1979), started following Du Meizhu on social media. As a hard-working single mother of a daughter, she said she sympathized with Du and wanted to show her some support. In a Weibo post published in 2024, she detailed how Du Meizhu began noticing Zhu’s online interactions in early 2022 and added her as a friend on WeChat.

In private conversations, Du shared complaints about her difficult life, and as the two talked more and more, Zhu began transferring small amounts of money to help. Over time, Du said she needed money for various things—from financial support for school to legal disputes and expensive medical treatments for family members. Between 2022 and 2023, Zhu claims she transferred nearly 200,000 yuan in total.

At the end of 2023, Zhu–who works as a taxi driver–urgently needed money due to a family crisis. She reached out to Du to ask if she could repay the money. According to Zhu, she only returned 30,000 yuan (US$4,180) and refused to pay more, even though at the same time, Du was allegedly flaunting luxury brand purchases and had plans to buy a villa.

On June 25, 2025, Zhu posted an update on her Weibo account, saying she had traveled to Ulanhot City in Inner Mongolia – Du’s hometown – to seek justice and report the case to local authorities.

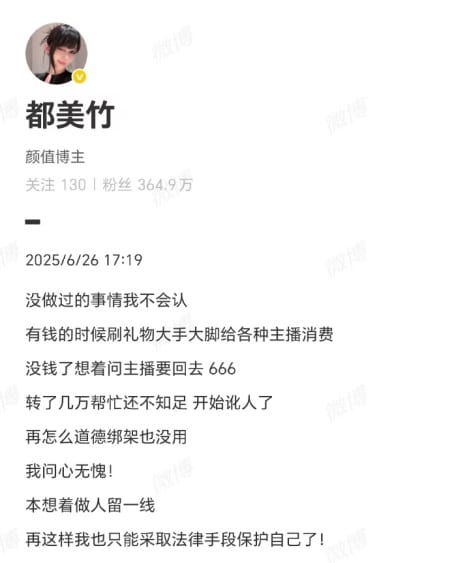

Du Meizhu has responded to the allegations on social media, writing that she “won’t admit to things I haven’t done.” She does not deny that Zhu gave her money.

She writes: “When she had money, she was lavishly spending it on gifts in all kinds of livestreams. Now that she’s broke, she wants it back from the streamers? After I transferred her thousands of yuan, she’s still not satisfied and is now starting to extort me. No amount of moral pressure will work. I have a clear conscience!”

The post by Du Meizhu

The case has blown up online. One post by Ms. Zhu has already received over 133,000 likes and is still gaining traction.

But the developments surrounding the case are puzzling to some. Du Meizhu has long maintained a social media image of wealth, showcasing a lifestyle filled with Dubai travel, horseback riding, luxury food, and fashion. Why would she need to take money from a single mum? Du is being criticized not only for faking her wealth, but also for accepting so much money from a woman who clearly needed the money for her own family.

Du Meizhu social media photos.

Although the story is attracting a lot of attention online because it exposes private conversations between Du and the woman – and, frankly, many netizens just enjoy the drama, – it also says a lot about China’s thriving livestreaming industry and just how close online followers can feel to the influencers they follow. In these kinds of online communities, it is common for fans and followers to send livestreamers money or ‘virtual gifts’.

In the case of Ms. Zhu, some netizens doubt that she can prove in court that she loaned Du the money instead of gifting it to her. People also criticize Zhu: why did she spend so much money on an online influencer instead of on her own daughter?

Either way, many Chinese netizens feel that it was not right of Du Meizhu to take advantage of a single mum like that. Even if she’s not legally wrong, they feel she lacks moral integrity.

Du’s most recent social media post—featuring her in so-called “old money fashion” outfits—has only added fuel to the fire. Dozens of commenters flooded the post with demands that she repay Ms. Zhu. Though Du seemingly tried to delete the negative comments, they kept pouring in. “At this rate, there won’t be any comments left,” one user wrote.

Whether or not Du Meizhu ultimately faces legal consequences, the backlash is already taking a toll. She might escape the courtroom, but won’t be able to escape the court of public opinion.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Jiehun Huazhai (结婚化债): Getting Married to Pay Off Debts

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Lured with “Free Trip”: 8 Taiwanese Tourists Trafficked to Myanmar Scam Centers

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Media12 months ago

China Media12 months agoA Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoThe “City bu City” (City不City) Meme Takes Chinese Internet by Storm

-

China Society9 months ago

China Society9 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media