China Memes & Viral

Our Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

From quirky potatoes to low-key vibes, we uncover 10 buzzwords that shaped China’s cultural and social landscape in 2024.

Published

11 months agoon

From ‘Chillax’ to ‘Digital Ibuprofen,’ this compilation of ten Chinese buzzwords and catchphrases by What’s on Weibo reflects social trends and the changing times in China in 2024.

At the end of each year, Chinese media outlets compile lists of the most impactful buzzwords that shaped public discourse. The most popular new words and expressions are generally listed by the Chinese linguistics magazine Yǎowén Jiáozì (咬文嚼字), which selects ten noteworthy buzzwords (十大流行语).

If you want to know more about the buzzwords that made it to Chinese official media’s lists this year, check out this post by Andrew Methven at RealTime Mandarin which is a top ten compilation of Chinese buzzwords of 2024 based on these lists.

Here, we’ve curated a different list: a special What’s on Weibo top 10 of buzzwords and catchphrases from 2024. Each term reflects a broader trend, which we’ll explore in this article. Many of these words were previously featured in our premium Weibo Watch newsletter, where we highlight a word of the week in every issue. (Subscribe to get our newsletter).

These words are not in order of popularity, but rather in order of appearance throughout the year.

#1: SOUTHERN LITTLE POTATOES

Nánfāng xiǎo tǔdòu (南方小土豆)

The term “Southern Little Potatoes” (南方小土豆) became all the rage in early 2024 in the context of the travel hype surrounding Harbin, which saw a huge influx of tourists from the warmer southern regions who came to the snow-blanketed city or other destinations in the Three Northeastern Provinces (东北三省: Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning).

The southern tourists were soon nicknamed “Southern Little Potatoes.” While visiting China’s cold northeast, they tend to stand out due to their smaller stature, light-colored down jackets, and brand-new winter hats. Their appearance not only contrasts with that of the typically taller and darker-dressed locals, but some people also think it makes them look like “little potatoes.” After the endearing term “Southern Little Potato” became popular due to a viral video, some southern tourists, especially women, also adopted this term to humorously describe themselves.

Very soon after it caught on, locals started using “Southern Little Potatoes” as a humorous marketing strategy to attract more southern visitors. Harbin street vendors began selling plush keychains of “Southern Little Potatoes,” and even local taxis invited the “baby potatoes” to get on board (“土豆宝宝请上车”).

Through jokes, memes, and media stories about these “potatoes,” a narrative came to life about the city of Harbin taking care of and pampering these “naive,” “little” visitors. Although the term is meant to be affectionate, some took offense, suggesting that since it predominantly refers to smaller women, it is actually sexist and reinforces stereotypical perceptions of southern Chinese women. While some critical bloggers argue that the term is harmful and derogatory, the majority of netizens continue to use it for light-hearted banter about the enthusiasm of southern visitors and the hospitality of the northerners welcoming them.

#2: SPRING MOUNTAIN STUDIES

Chūn Shān Xué (春山学)

“Spring Mountain Studies,” or “Chunshan Studies” (春山学), became a viral phenomenon on the Chinese internet following the CMG Spring Festival Gala earlier this year. It was the buzz of the show, capturing widespread attention and sparking heated debates. The phrase “Chunshan Studies” arose from the controversy surrounding the performance by Bai Jingting (白敬亭), Wei Chen (魏晨), and Wei Daxun (魏大勋).

Popular actor and singer Bai Jingting, alongside co-performers Wei Chen and Wei Daxun, performed the song “Going Up Spring Mountain” (上春山). While the song itself wasn’t particularly remarkable at first glance, it quickly became the center of attention due to the staging arrangement: the three singers were positioned on a tiered platform representing a mountain, with Bai standing on the highest pedestal.

Controversy arose when Bai remained on the top pedestal after his part, seemingly blocking Wei Daxun from taking the higher position. As a result, Wei performed from a lower step, creating choreographic asymmetry and apparent confusion on stage. Speculation grew that Bai may have intentionally stayed in the prominent position to draw more attention.

Adding to the rumors was Bai’s choice of attire—he wore all black, while Wei Chen and Wei Daxun were dressed in white. Netizens suggested this made him stand out even more. Rehearsal footage posted online fueled these suspicions. In one rehearsal video, Bai stepped down after his part as expected and wore white like the others. This led to accusations that he deliberately changed his outfit and position during the live performance to ensure he stayed at the center of attention.

The timing of these changes also raised eyebrows. Since the Spring Festival Gala is a live event, but typically runs a recorded dress rehearsal alongside the live broadcast for contingency purposes, any significant alterations to staging or wardrobe would prevent producers from seamlessly switching to the pre-recorded version. Critics argued that Bai’s supposed changes sabotaged this fallback option, leaving producers unable to correct the perceived imbalance.

The controversy ignited widespread criticism of Bai Jingting, with detractors accusing him of selfishness and poor character. Social media erupted with debates, and the term “Chunshan Studies” was coined humorously to describe the detailed analysis and theories surrounding the incident.

Online communities, particularly on platforms like Douyin and Bilibili, became hubs of “Chunshan Studies,” as netizens scrutinized every detail of the performance. Videos dissecting wardrobe choices, body language, and stage movements frame by frame went viral. What began as speculation about Bai’s intent turned into a pseudo-academic field, blending elements of popular culture analysis, media discourse, and social studies.

Some commentators argued that the discussion reflected deeper issues about equity and ethical behavior in the entertainment industry, elevating the controversy beyond a simple song performance. Who would have thought that a single performance of “Going Up Spring Mountain” could spark such an intellectual and cultural phenomenon?

#3: MELLOW PEOPLE

Dàn rén (淡人)

“Mellow People” (淡人) is a term that emerged in 2024 to describe the mental state of young people in China today. The word dàn 淡, which I’ve translated as ‘mellow’ in this context, carries a range of meanings in Chinese: it can imply lightness, calmness, indifference, paleness, or even triviality.

To be a dàn individual, a dànrén 淡人, has become a way for young people to express how they navigate life. They might want to quit their uninspiring job, but it pays the bills—so it’s okay. They endure hours of commuting every day because the rent is cheaper—so it’s okay. They’re pushed into blind dates by their parents, even though they’d rather not go, but they lack the energy to resist—so it’s okay.

Being ‘mellow’ or ‘unperturbed’ means remaining indifferent in a calm, lighthearted way. Similar to earlier Chinese popular expressions like “lying flat” (躺平) or being “Buddha-like” (佛系), it’s a way of coping with the pressures and challenges of modern life. However, it’s slightly more optimistic than outright passivity (like lying flat): it reflects a passive acceptance of life as it is, embracing the monotony of daily routines and competitive work environments without resistance.

The concept of being a dànrén has even developed into its own pseudo-discipline, referred to as 淡人学 dànrén xué, which might be translated as ‘Mellowism’ or, perhaps more aptly, ‘Unperturbabilism.’

#4: “BACK TO THE ROOT”

Dāngguī (当归)

The term dāngguī 当归, freely translated as “back to the root,” came up this year in the context of the propaganda campaign surrounding reunification with Taiwan. Since earlier in 2024, dāngguī is used by Chinese state media in the slogan “Táiwān dāngguī” (#台湾当归#), which means “Taiwan must return [to the motherland].” Separately, the two characters in dāngguī 当归 literally mean “should return.”

However, the slogan is a play on words, as the term dāngguī (当归) as a noun actually means Angelica Sinensis, the Chinese Angelica root or ‘female ginseng,’ a medicinal herb commonly used in traditional Chinese medicine, native to China and cultivated in various East Asian countries.

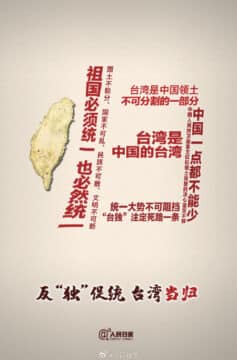

Poster by People’s Daily. ‘Taiwan’ on the left side resembles a piece of ‘female ginseng’.

This play on words is also evident in the poster disseminated by People’s Daily, where Taiwan is depicted on the left and resembles a piece of the yellowish ‘female ginseng’ root. It is part of the character “归” (guī, to return, go back to). The remainder of the character consists of various slogans commonly used by Chinese official media to emphasize that Taiwan is part of China.

Because of this context, where dāngguī 当归 both refers to the discourse of Taiwan returning to China and to the female ginseng root, a creative translation would be “back to the root.” If you want to be less creative, you could also say it’s the Taiwan “should return” campaign.

#5: CHILLAX

Sōngchígǎn (松弛感)

In recent years, the pursuit of a certain “relaxed feeling” has gained popularity across the Chinese internet. Sōngchígǎn is a combination of the word for “relaxed,” “loose” or “lax” (松弛) and the word for “feeling” (感). Initially used to describe a particular female aesthetic, the term evolved to represent a lifestyle where individuals strive to maintain a relaxed demeanor, especially in the face of stressful situations.

The concept gained traction online in mid-2022 when a Weibo user shared a story of a family remaining composed when their travel plans were unexpectedly disrupted due to passport issues. Their calm and collected response inspired the adoption of the “relaxed feeling” term (also read here). Central to embodying this sense of relaxation is being unfazed by others’ opinions and avoiding unnecessary stress or haste out of fear of judgment. Nowadays, Chinese cities aim to foster this sense of sōngchígǎn. Not too long ago, there were many hot topics suggesting that Chengdu is the most sōngchí 松弛, the most relaxed city in China. This sentiment was further reinforced in 2024 when ‘Chengdu Disney’ emerged as a quirky new hotspot (read here).

As for individuals, the most sōngchígǎn person of the year was undoubtedly Olympic athlete Quan Hongchan (全红婵). The young springboard diver from Guangdong became a multi-medalist at the Paris Olympics, going viral for her quirkiness and authenticity. Chinese netizens describe her as “being Guangdong-style relaxed” (“广式”松弛感), not just for her unique sense of style (she loves her “ugly fish slippers”), but for her ability to remain chill while dozens of cameras focus on her.

#6: STRONG STEALTH VIBE

Tōugǎn hěn zhòng (偷感很重)

It’s that moment when you see someone you know and pretend to be busy on your phone to avoid social interaction. Or when someone takes a group picture and you’re unsure how to pose. Or when all eyes are on you and you wish for an invisible cloak.

In 2024, the term “tōugǎn” (偷感) emerged on Chinese social media. Tōugǎn (偷感) literally translates to “stealth sense” or “secret feeling,” but we can interpret it as an overall vibe of being “under-the-radar.” The phrase “tōugǎn hěn zhòng” (偷感很重) means “the stealth sense is strong,” and can be used to describe someone as being “very under-the-radar” or having “a strong stealth vibe.”

The exact origin of this term is unclear, but it likely first appeared on Xiaohongshu in response to a videoclip by the South Korean girl group Le Sserafim for their single “Easy,” where they sing and dance effortlessly with some low-key dance moves.

Tōugǎn (偷感) is used by and resonates with China’s Gen Z to express a common feeling in their daily lives, where they prefer to go about things quietly and low-key, avoiding too much attention. They can still be smooth and effortless, but out of fear of embarrassment or judgment, they do so in a subtle and low-profile manner. They won’t flaunt their achievements, but wait for others to notice them. Unlike earlier internet buzzwords where young people mock themselves, tōugǎn is not negative – it’s a bit tongue-in-cheek and a way for people to connect over their inner worlds that aren’t visible to others.

#7: CITY BU CITY

City不City啊

The phrase ‘City bu City a’ (City不City啊), translated as “City or not?”, took the Chinese internet by storm in the summer of 2024. The phrase became popular thanks to American influencer Paul Mike Ashton, nicknamed “Bao Bao Xiong” (保保熊, Baby Bear), who runs a Chinese-language account on Douyin. On his channel, Ashton shares humorous snippets about his life in China, where he works as an entertainer and tour guide.

In one video from April this year, Ashton posted a clip in which he cycles through the city like a Shanghai ‘city girl’ who often mixes Chinese and English words, calling himself “very city” (“我是好city”). He says: “I’m so city, a city girl. It’s so cool, breezy. Life in the city is so good, I feel so free.” Ashton later began incorporating this phrase more frequently in his humorous videos, sometimes also involving his sister.

Walking on the Shanghai Bund, the brother and sister describe Shanghai as “so city” (“好city啊”). While walking on the Great Wall, Bao Bao asks his sister if it’s “city or not” (it’s not). In other videos in which the two are traveling throug China, Ashton repeatedly asks his younger sister if certain things are “city or not,” to which she usually responds humorously: “It’s very city.” In this context, “city” has evolved from a noun into a quirky adjective, describing something that embodies the essence of urban life; something that is ‘city’ is metropolitan, lively, and modern. It’s very tongue-in-cheek and also serves as a playful commentary on how young Chinese people often mix Chinese and English words to sound more sophisticated and trendy.

This phenomenon sparked the ‘city or not’ meme, which even reached the Foreign Ministry this week when spokesperson Mao Ning was asked about it. She responded that she had heard about the new use of the phrase and that it is a positive sign of foreigners enjoying life in China. Chinese authorities and state media have also jumped on this trend to promote tourism. The meme has been imitated and adapted by various local tourism departments. Ashton himself has encouraged foreigners to come and experience Chinese culture (and its very ‘city’ city life), further boosting its popularity. By now, the phrase has become ingrained in China’s digital culture.

#8: FAN CULTURED

Fànquānhuà (饭圈化)

Around the time of the Olympics and the skyrocketing popularity of Chinese table tennis players, the word ‘fan-cultured’ or ‘fandom-ization’ (fànquānhuà 饭圈化) became increasingly popular in 2024. While fànquān 饭圈 literally means “fan circle,” the suffix huà 化 is generally used to indicate a process of transformation or turning into something, similar to the “-ization” suffix in English.

The term fànquānhuà 饭圈化 refers to the recently much-discussed phenomenon where something—often outside the realms of entertainment—receives passionate support from people who begin to form online fan circles around it, changing the dynamics in ways that resemble the relationships between celebrity idols and their fans.

This year, it became clear how Chinese fans started to form extremely strong communities around China’s table tennis stars, defending them as if they were idols. This fan behavior was harshly criticized by Chinese authorities this year, as they see it as toxic fan culture that goes against the Olympic spirit (read more).

However, “fandom-ization” extends beyond sports. For instance, Chinese pandas have similarly strong fan club dynamics. Even inanimate objects can become “fan-cultured.” A notable example is the Little Forklift Truck (小叉车) that played a role in constructing the Huoshenshan emergency specialty field hospital during the early days of the Covid crisis.

The construction process was live-streamed, and millions of viewers found the hardworking little truck so cute and brave that it too became “fan-cultured.”

#9: RUSHING TO COUNTY-LEVEL TOWNS

Bèn xiàn (奔县)

The term “rushing to the county,” bèn xiàn (奔县), surged in Chinese media after the 2024 National Day holiday. This time, the peak travel period saw increased popularity for lesser-known county-level towns instead of large cities or famous tourist destinations. According to travel industry reports following the week-long holiday, bookings significantly increased compared to 2023, which was already a notably crowded year.

In 2024, 765 million trips were taken nationwide, marking a 10.2% increase compared to pre-pandemic 2019. In 2023, ‘domestic travel’ was the key trend, with the so-called “special forces travel” (tè zhǒng bīng lǚxíng 特种兵旅游) becoming popular among Chinese youth. That trend focused on visiting as many places as possible at the lowest cost within a limited time, often involving incredibly tight schedules and 12-hour travel days.

In 2024, the focus shifted to a more relaxed and cost-effective approach, turning county-level tourism (bèn xiàn yóu 奔县游) into a new trend. People are no longer just visiting county-level towns to see family; more young travelers from China’s major cities are exploring nearby smaller towns for “micro-holidays” (wēi dùjià 微度假).

County-level towns in China are smaller than major cities like Beijing or Shanghai but are still large enough to offer plenty to do, as they serve as important hubs for the surrounding rural areas. In these county-level destinations, the cost of hotels and meals tends to be much cheaper than in popular tourist hotspots. Staying closer to home also reduces travel time and expenses while offering the chance to visit lesser-known locations and avoid peak tourist crowds.

According to The Observer, during the 2024 National Holiday, places like Jiuzhaigou, Anji, Shangri-La, Pingtan, Dujiangyan, and Jinghong saw booking increases of 109%, 86%, 74%, 67%, 51%, and 50%, respectively.

#10: DIGITAL IBUPROFEN

Diànzǐ bùluòfēn (电子布洛芬)

The term “Digital Ibuprofen” or “Electronic Ibuprofen” came up this year when fans told Chinese actor and singer Tan Jianci (檀健次) that he is their “digital ibuprofen.” Tan, with a puzzled look, asked what that meant. A fan explained, “It means we feel better when we see you” (or, essentially, “our bodies feel no pain”). Since then, Tan Jianci has become associated with the term “digital ibuprofen.”

The term has been around for some time, gaining popularity in 2022-2023 among fans of entertainment shows. It refers to content that provides relief from stress or discomfort, much like how ibuprofen alleviates physical pain. For instance, the Hunan TV show Go for Happiness (快乐再出发) is often called “digital ibuprofen.”

The term saw a surge in popularity alongside the Japanese animated series Chiikawa, which became a viral hit among young people. The anime’s portrayal of its cute character staying optimistic despite life’s stresses earned Chiikawa the nickname “digital ibuprofen,” as fans found comfort in its stories (read more in this story by Sixth Tone).

“Digital ibuprofen” applies to more than just shows—it can be any content, such as videos, memes, or idols, that provides comfort, distraction, and relief to fans. In the same category, there’s also “digital pickled mustard” or “electronic pickled mustard” (电子榨菜, diànzǐ zhàcài), which refers to a binge-worthy or comforting show. *The term 电子 (diànzǐ) means “electronic” and is commonly used in modern Chinese terms, much like the English “e-” prefix in ebook (电子书) or email (电子邮件). It’s also used for digital transactions, like digital payments (电子支付) or digital wallets (电子钱包).

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Memes & Viral

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

The meeting between US President Donald Trump and new Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi became a popular topic on China social media, thanks to a stream of meme-worthy moments.

Published

2 weeks agoon

November 2, 2025

It was a pleasant autumn day in Tokyo on October 28, when Trump first met Japan’s newly-elected Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi (高市早苗).

Takaichi welcomed Trump at the State Guest House as her first foreign guest since taking office as Japan’s first-ever female leader, offering what Yomiuri Shimbun described as “Takaichi-style hospitality.”

During the visit, Trump and Takaichi held a bilateral summit during which Takaichi expressed desire to build a new “golden age” for the US-Japan alliance. Afterwards, they signed agreements and exchanged gifts — a golf bag for Trump, signed by Japanese golf star Hideki Matsuyama (with whom Trump has previously played), and “Japan is Back” baseball caps for Takaichi.

Following a lunch that featured Japanese vegetables and American steak, the two visited the US Navy’s Yokosuka base, where Trump remarked that he and Takaichi had “become very close friends all of a sudden.”

On Chinese social media, the meeting drew considerable attention.

There has been heightened focus in China on Sanae Takaichi beyond anti-Japanese sentiment and her recent appointment as Japan’s first female Prime Minister — as she is widely regarded as a far-right politician who denies, downplays, or glorifies historical facts related to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1931-1945).

Japan’s official narrative of its wartime past has long been a major obstacle to deeper reconciliation between China and Japan, and it is highly unlikely that Takaichi’s views of the war are going to bring China and Japan any closer. Among others, she is known for visiting Yasukuni Shrine, the Tokyo shrine that honors Japan’s war dead (including those who committed war crimes in China). She also claimed that Japan’s aggression following the Manchurian Incident, which led to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, was an act of “self-defense.”

In light of these tensions in Sino-Japanese relations, and because of the changing dynamics in the current US-China relationship, many details surrounding the Trump–Takaichi meeting became popular talking points.

🔴 Trump: Reaffirming US Dominance, Insensitive to Japan’s Wartime Past

Many netizens focused on moments they interpreted as Trump asserting dominance or showing disregard for Japan.

👉 One awkward moment showed how, during the welcoming ceremony, Takaichi failed to properly escort the US president. He walked ahead of her twice, and, despite the cues to salute the Japanese flag, Trump simply walked past it instead, leaving Takaichi looking visibly surprised (video).

While some saw it as a case of poor etiquette instructions behind the scenes, most reactions framed it as a sign of power dynamics in the US–Japan relationship, with some commenting: “Why would the master bow to his son?” (Hashtags: “Trump Skips the Japanese Flag” #特朗普略过日本国旗# and “Trump Ignores Takaichi Twice in a Minute” #特朗普1分钟内两次无视高市早苗#)

👉 Another widely discussed moment came at the Yokosuka base, where Trump invited Takaichi on stage and mentioned how their bond was based on WWII (“Born out of the ashes of a terrible war”) — a comment that seemed to catch Takaichi off guard (video). He quickly followed up with, “our bond has grown into the beautiful friendship that we have,” but not before her expression visibly changed.

Under the hashtag “Trump’s Remark Gave Takaichi a Scare” (#专家:#特朗普一句话吓了高市早苗一大跳#), Chinese media outlet Beijing Time (@北京时间) commented: “She was afraid that Trump might go on to say something she couldn’t respond to easily.”

Image by online creator.

👉 Later, at a reception at the US Embassy in Tokyo, Trump referred to the Pacific War as a “little conflict.” While the euphemism may have been aimed at promoting reconciliation (“We once had a little conflict with Japan — you may have heard about that — but after such a terrible event, our two nations have become the closest of friends and partners…” video), many Chinese netizens and outlets, including The Observer (观察者网) interpreted the remark as dismissive. This fueled hashtags like “Trump Calls the Pacific War a Small Conflict” (#特朗普将太平洋战争称作小冲突#) and “Trump Refers to Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombing as a Small Conflict” (#特朗普称轰炸广岛长崎只是小冲突#).

🔴 Takaichi: Smiles & Body Language Seen as Deferential to US

Alongside critiques of Trump’s behavior, much attention was also paid to Takaichi’s facial expressions and body language.

On Chinese social media, she was widely seen as overly eager to please — described as “fawning over Trump” (谄媚) in an “exaggerated” (夸张) way. Global Times highlighted how even Japanese netizens were criticizing her gestures as inappropriate for a prime minister (#日本网民怒批高市早苗谄媚#).

Some jokingly drew comparison to the famous movie about Hachiko, the loyal Japanese dog and his owner, played by American actor Richard Gere.

Some commenters described her behavior as that of an affectionate “pet” eager for approval.

Meme in which Takaichi was compared to Captain Jia (贾贵), known for his exaggerated flattery and traitorous behavior.

One meme compared Takaichi’s expressions toward Trump to those of Chinese actor Yan Guanying (颜冠英), who played the supporting role of Captain Jia (贾贵) in Underground Traffic Station (地下交通站), a satirical Chinese sitcom set during the Japanese occupation. The character was known for his exaggerated flattery and traitorous behavior.

🔴 Trump & Takaichi: A US-Japan Love Affair

But the most popular kind of meme surrounding the Takaichi-Trump meeting portrayed them as a newly smitten couple or even newlyweds. AI-generated images and playful commentary suggested a “love affair” dynamic. Watch an example of the videos here.

AI-generated images circulating on social media.

Some netizens linked this imagery to deeper historical dynamics — drawing distasteful parallels to American troops in postwar Japan and the women involved with them, including references to the reinstatement of the “sexual entertainment” industry once used to serve US forces.

For many, however, it was more about humor than history.

Some shared images showed just how much happier Trump seemed to be meeting with Sanae Takaichi than with her predecessor, Shigeru Ishiba, in 2024.

A considerably warmer meeting.

In the end, there are two sides to this peculiar “love affair” meme.

👉 On one hand, it plays on the affectionate behavior and newfound friendship between the two — Trump held Takaichi close to him multiple times, and she said she would nominate him for the Nobel Peace Prize. At the same time, the portrayal reduces Takaichi to a submissive romantic partner rather than a political equal, reinforcing gendered stereotypes — a dynamic that likely wouldn’t have emerged as strongly if she were a man.

This kind of “couple pairing” is quite ubiquitous in Chinese digital culture, especially involving people who are unlikely to have an actual relationship in real life. And although censorship would never allow this kind of pairing to thrive online if it involved Chinese politicians, the fact that it features Trump and Takaichi makes it less susceptible to online control.

A previous example of a noteworthy “love affair” meme was the one pairing US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi with Chinese political commentator Hu Xijin (see it here).

👉 Second, the Trump–Takaichi meeting is often placed in a Chinese context — showing the two getting married in a Chinese-style ceremony or inserting them into Chinese film scenes. While this may seem like light banter, it also reveals a deeper layer to the discussion: many believe that China plays a central role in the US–Japan relationship, interpreting the meeting through a Chinese lens in which US–China dynamics and the history of Sino-Japanese war are all interconnected.

Will they live happily ever after? Some may fantasize they will — but others think the weight of the past, both American and Chinese, will always cloud their sunny future. For now, most enjoy the banter and how “political news has turned into a romance variety show” (“政治新闻愣成了恋综了”).

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From a tragic “wild child” case in Yunnan to the farewell of Nobel laureate Yang Chen-Ning, here’s what’s trending on Weibo and beyond this week across Chinese social media.

Published

4 weeks agoon

October 19, 2025

🔥What’s Trending in China This Week (Week 42, 2025)? Stay updated with China Trend Watch by What’s on Weibo — your quick overview of what’s trending on Weibo and across other Chinese social media.

1. “Wild Child” from Yunnan Sparks Concern and Investigation

Screenshots circulating on Chinese social media showing the “wild child” in Yunnan.

A tragic and widely discussed story from Yunnan has been trending on Weibo this week, centering on a 3-year-old boy from Nanjian County who was spotted near a highway service area — naked, neglected, and walking on all fours. Online videos led Chinese netizens to dub him the “feral child.”

There have been conflicting media reports on the case over the past few days. From The First Scene (@第一现场) to Shanghai Reporter (上观新闻) some claimed the child’s parents are impoverished and jobless while others reported the father and mother are actually highly educated and do have resources, but that the choice to raise their child like this is related to lifestyle philosophy. The parents reportedly insisted that the child used to suffer from eczema and found clothes irritating and painful, so “he doesn’t like wearing clothes.”

One thing that local villagers quoted in these reports agree on is that the situation is “not normal.” The child, who never wears clothing, allegedly mimics animal behavior and refuses to eat from his hands — preferring to eat food off the ground. Locals previously already villagers reported the situation to the police.

Authorities in Nanjian County have announced the creation of a special task force to investigate this case. Officials said no signs of human trafficking were found, and that the parents are currently outside Yunnan Province. According to Beijing Youth Daily, The child and his parents are now under supervision, although it is not clear what this actually means – since other sources say the parents are not willing to cooperate. They also have another boy, who is currently one year old. Authorities have also investigating whether the parents’ behavior constitutes a crime.

Manya’s Take:

The “wild child” story brings back memories of the Xuzhou mother of eight. That heartbreaking case also gained national attention after netizens shared a video showing a woman chained up in a shed next to her family home. The chaotic media coverage of that case mirrors what we’re seeing now: media outlets are quick to jump on the story, while local authorities — feeling public anger and pressure — rush to investigate, resulting in conflicting reports, rumors, and fake news. Both situations involve rural counties that would otherwise hardly ever make headlines, with local authorities often unequipped to handle such crises quickly. Hopefully, there will be a clearer update on this story soon.

2. China Responds to Trump’s Remarks on Soybean Trade and Cooking Oil

Soybeans have been trending this week. As China is boycotting American soybeans – the fourth most sold agricultural product from the country – farmers in the US are facing uncertain times, as it’s harvesting season and the biggest purchaser of soybean exports is China.

On Tuesday, Trump wrote on Truth Social that China was “deliberately halting U.S. soybean imports,” calling it an “economically hostile act.” He also threatened to terminate business with China regarding cooking oil and other areas of trade as retribution.

On Chinese social media, people seemed unimpressed. The term TACO is also seen more often, a popular abbreviation for “Trump Always Chickens Out.” The Foreign Ministry dismissed Trump’s claims as “unfounded” and emphasized China’s commitment to normal trade relations. On Weibo, commentator Hu Xijin wrote: “Haha, so he [Trump] slaps tariffs on China and blocks chip exports and that’s not considered ‘hostile’? But when China doesn’t buy soybeans, suddenly it is? What kind of logic is that!”

Manya’s Take:

Chinese netizens are treating this latest trade exchange with irony rather than outrage, not only viewing it as a sign of US inconsistency on trade but also there’s some banter about the ‘cooking oil’ threat: when the US side talks about banning imports of “Chinese cooking oil” many assume they meant edible oil (食用油), while what the US actually imports from China is used cooking oil (UCO, 废食用油/地沟油) — waste oil that’s recycled to make biofuels. So the joke is that even Trump himself is seemingly mixing up cooking oil and used cooking oil, moreover threatening a ban that would hurt itself more than China, turning this trade spat into a moment of internet humor.

3. Nanjing Deji Plaza Faces Backlash Over VIP-Only Restrooms

The exclusive members-only restroom at Nanjing’s Deji Plaza.

Nanjing’s luxury shopping mall Deji Plaza (德基广场) has sparked controversy after introducing members-only restrooms accessible exclusively to VIP members (天象会员) who spend over 200,000 yuan ($28,000) annually. Access requires scanning a Deji membership QR code.

Beyond offering peace and privacy, the restrooms feature Tom Ford vanity sets, Jo Malone handwash, and Dyson hairdryers. One Xiaohongshu blogger (and VIP member) noted, “The maintenance cost here is ten times that of a regular restroom.”

After news of the VIP restrooms went viral, it fueled debate about turning ‘a basic human need’ into a ‘class privilege’ or “privatizing a public facility.” One user commented, “Now even restrooms have to reflect the wealth gap?”

Despite the criticism, curiosity grew — many users purchased “code-scanning services” on secondhand platforms to gain access, quickly undermining the restroom’s exclusivity. In response to the controversy, Deji Plaza stated that the members-only restrooms would soon be dismantled and converted into a regular public facility. Regardless, and despite the backlash, the initiative seems to have been fruitful in terms of brand name recognition, as it got everyone talking about Deji Plaza.

Manya’s Take:

There’s some irony in this story: there’s controversy over a mall toilet being “VIP,” yet at the same time, it’s the exclusivity that makes people want to try it. According to the latest posts on Xiaohongshu (XHS) by Deji Mall visitors, the VIP toilets are already gone, and people are back to complaining about the restrooms being too crowded and dirty. One XHS commenter (西蒙吴) had the best take on the issue: in a time when Chinese media are working to downplay the country’s wealth gap and ease public resentment, Deji Mall made the right move by dismantling the card-access VIP toilets — if not for the pressure of online public opinion, authorities might have stepped in themselves. It was an unwise move simply because it was all about a toilet: unlike VIP waiting areas or service counters, consumers don’t like restrooms being divided by class. A smarter approach would have been to create a VIP lounge that just happens to include a restroom.

4. Arc’teryx Responds to Tibet Fireworks Show Environmental Damage Investigation

The controversial fireworks show held in Tibet on September 19.

This is a topic that has sparked outrage and continued discussion in China over the past weeks. On September 19, a major fireworks event was held at an altitude of around 5,500 m or 18,000 feet in Tibet’s Himalayas, created by famous Chinese artist Cai Guoqiang (蔡国强) and sponsored by the outdoor brand Arc’teryx.

The 52-second show, titled “Ascending Dragon” (升龙) was supposed to impress people for its spectacular and colorful use of 1,050 fireworks, but it triggered outrage instead: critics blasted it as tone-deaf commercialization and ecological abuse of sacred and fragile land, and soon an investigation was launched.

Now, the outcome of that investigation has also become a major talking point as it revealed disturbance to local wildlife and caused significant environmental damage of over 30 hectares of grassland.

Cai Guoqiang and his studio will be held legally accountable for environmental damage, and Arc’teryx, as a sponsor of the event, will also bear legal responsibilities. Furthermore, the relevant county officials who had initially approved the show without going through the proper channels are also punished: Party Secretary Chen Hao (陈浩) has been dismissed, and nine other county officials received formal penalties ranging from removal to warnings.

Manya’s Take:

A lot has already been said and written about this controversy. What it comes down to, in the public perception in China, is that the high ambitions and personal goals of the artist and the Arc’teryx brand — which built its image around environmental responsibility and authentic outdoor culture — were pursued at the expense of Tibet’s fragile environment and marginalized communities. Their so-called “dreamlike” event left lasting scars for a fleeting 52-second spectacle. More than just serving as a warning for brands to ensure their actions align with their “eco-friendly” promises, this entire case will undoubtedly go down in history as a moment of awareness — a case study for future art events and large-scale performances in nature in China — on what not to do, and on how to balance spectacle with responsibility.

5. Nobel Laureate Yang Chen-ning Passes Away at 103

Yang Chen-ning passed at the age of 103.

The death of the renowned Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), also known internationally as Chen-Ning Yang, China’s first Nobel laureate in physics, has been trending across Weibo, Douyin, Zhihu, and Toutiao in recent days. Yang passed away in Beijing on October 18, 2025, at the age of 103, just weeks after celebrating his birthday on October 1.

On social media, Yang is remembered as a legendary physicist who devoted his life to science and truth. He shared the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physics with Li Zhengdao (李政道) for discovering parity violation in weak interactions, and co-developed the Yang–Mills theory with Robert Mills in 1954, a cornerstone of modern particle physics.

Many online tributes also recall Yang’s lifelong friendship with nuclear physicist Deng Jiaxian (邓稼先, 1924–1986). The two met in middle school and went on to become giants of Chinese science. Yang’s wife, Weng Fan (翁帆), has also become part of the online remembrances. Over 50 years his junior, she met Yang while she was a student; they married when she was 28 and he was 82. Her tribute to Yang, expressing gratitude for having shared his company for many years, has received over 140 million views on Weibo.

Manya’s Take:

There is certainly a strong sense of national pride in the accomplishments of Yang Chen-Ning, but on social media, much of the attention also centers on his relationship with his wife, who was 54 years younger. Many see Yang’s passing as a moment of reflection — was she there for the money and fame, or for love? Opinions are divided, but the fact remains that the two were married for over twenty years, and she stayed by his side throughout. Some argue that Yang was simply so extraordinary, in both mind and body, that he naturally connected with younger people — and they with him. Others say their love was “timeless,” that true soulmates (灵魂伴侣) do not see age. Either way, it’s clear that 2025 netizens aren’t all cynics — there are quite a few romantics out there.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

“It’s in the Details” – The Xi-Trump ‘G2’ Meeting on Chinese Social Media

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral4 months ago

China Memes & Viral4 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest