China Digital

Privacy or Convenience? Forced Deletion of WeChat Contacts Generates Surprising Reaction from Chinese Netizens

The story of an aggrieved employee forced to delete his WeChat contacts by his boss has brought more applause than outrage on the Chinese Internet.

Published

7 years agoon

By

Gabi Verberg

The case of an employer, abusing her power to make one of her employees delete all his colleagues from WeChat, became a hot topic on Chinese social media earlier this week. As the news hit over 350 million views, few netizens worried about the employees’ deprivation of privacy and more discuss the advantages of being forced to clean up your WeChat contacts.

On November 18, the hashtag “Prior to Resignation, Employee Is Required to Delete Colleagues from WeChat” (#辞职先删同事微信#) went viral on Chinese social media, racking over 350 millions views.

On July 26, a Ping’an Life Insurance Company (平安人寿保险公司) employee, surname Wang, handed in his letter of resignation. To complete the resignation process, his employer, surname Kou, demanded he delete all the contacts of Ping’an co-workers from his WeChat. Wang complied and moved without a fuss, but not for long.

Unable to ignore his unease at the way he had been treated, Wang inquired the HR department of Ping’an on the resignation procedure, only to find that deletion of one’s co-workers’ WeChat contacts is in no way obligatory.

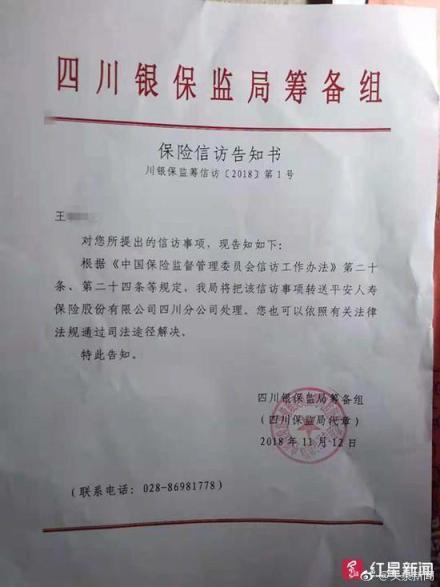

Feeling aggrieved at having had his privacy infringed upon, Wang repeatedly tried to get an apology from his former employer, even turning in a letter of complaint to the Sichuan Bank and Insurance Regulation Bureau (四川银保监局). However, the apology never arrived –that is, until the matter caught the attention of Chinese netizens.

Red Star News (红星新闻) was the first media outlet to obtain a statement from Kou on the incident.

Though she did not deny asking Wang to delete his contacts, she denied having forced him to do so: “He is 1.80 meters tall, and I am only a little taller than 1.50 meter. If he hadn’t agreed to cooperate, I would never have been able to force him,” observed Kou.

She went on to explain that the decision was for the benefit of the company. With competing insurance companies constantly snapping up each other’s employees, Kou believed Wang’s possible defection to one of Ping’an’s rivals would have a demoralizing effect on her team.

“Wang was employed with us for three years,” said Kou: “I brought him into this industry, taught him how to seal the deal and keep a good relationship with customers. To educate somebody in this industry is not an easy job.”

“WeChat “friends” are anything but friends.“

Fortunately for Kou, many netizens construed the incident as a disguised cure for a perpetual problem all WeChat users face – WeChat “friends” that are anything but friends.

“If your relationship with a colleague is good, add him back. If the relationship is not good, then don’t. It will only clean up your phone,” one netizen commented.

Another Weibo user, ignoring Wang’s grievances, observed: “This is perfect, now you don’t need a reason to finally delete those people you don’t like.”

Granted, there were some who criticized Kou’s handling of the situation, viewing the incident as an indictment of the at times sketchy insurance industry. However, many showed empathy towards Kou’s predicament, one netizen asserting that “Kou is just scared [Wang] will take other colleagues to his new company.”

In any case, the general consensus is not in Wang’s favor; netizens mostly agree that it is not unreasonable for companies to demand employees who just resigned to withdraw from any “work group chats.”

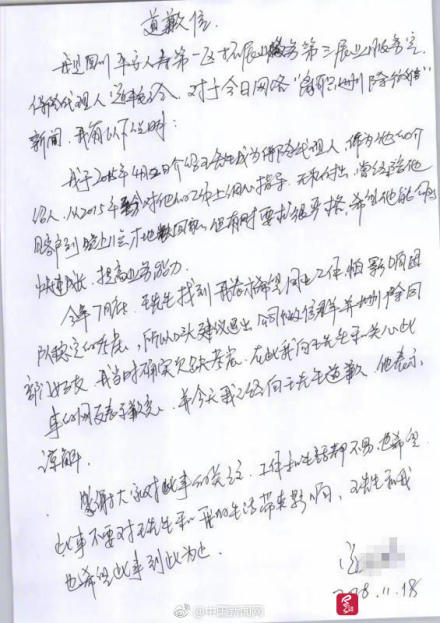

On November 19, the day after the news went viral, Ping’an issued a letter of clarification saying they regretted the situation was handled, followed a hand-written letter of apology from Kou, who acknowledged her lack of consideration.

Apology letter by Kou.

This was enough to satisfy Wang it seems, as both letters mention that all parties had now settled the issue.

By Gabi Verberg, edited by Eduardo Baptista.

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Gabi Verberg is a Business graduate from the University of Amsterdam who has worked and studied in Shanghai and Beijing. She now lives in Amsterdam and works as a part-time translator, with a particular interest in Chinese modern culture and politics.

China Digital

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

From digital stress to “dangerous Japan,” here are the trends that stood out this week on Chinese social media.

Published

3 days agoon

February 12, 2026

🔥 China Trend Watch (week 6/7 | 2026) Part of Eye on Digital China by Manya Koetse, China Trend Watch is an overview of what’s trending and being discussed on Chinese social media. The previous newsletter was a chapter dive into the Becoming Chinese and Kill Line phenomena. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

In the first weeks of 2026, our news feeds have felt unusually heavy. From war, protests, and heightening geopolitical tensions, to the Epstein files and the sentencing of Jimmy Lai, there is so much competing for scroll space on our phones these days. The Winter Olympics and the start of the Chinese New Year travel season bring some light to otherwise darker feeds, but still add to the endless stream of TikTok trends and Temu/Tmall temptations that quickly move beneath our thumbs just before we switch off the screen and dim the nightlight for sleep.

It is hardly surprising that the mental health of many internet users is increasingly affected by media overload, closely tied to today’s never-ending news delivery & social media ecosystems accompanying us in busy lives, where our minds are also occupied with our own daily worries and pressures.

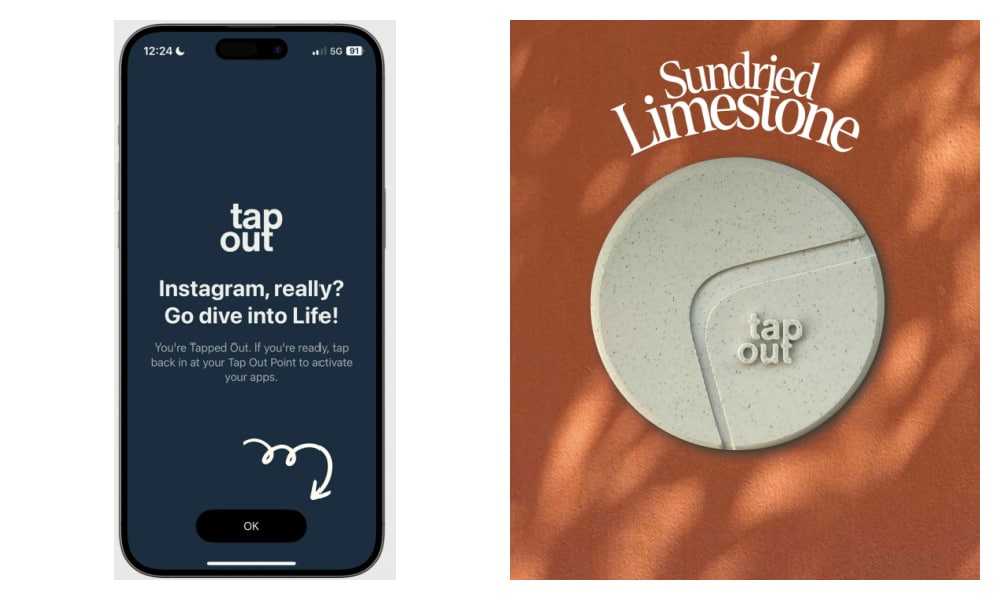

Lately, this became a topic of discussion in a digital group chat I share with my friends in Amsterdam. They found a practical way to distance themselves from the feeds on their phones: the Tap Out, an app blocker designed by two Dutch guys that only lets them access distracting apps by physically tapping a small “Tap Out Point,” a compact NFC-enabled puck available in different colors with fancy names like Sundried Limestone and Marbled Moon. By placing the puck in another room, or even leaving it at home while at work, a physical barrier prevents them from getting trapped in mindless doomscrolling and addictive swiping habits.

I found the sudden popularity of the tool somewhat bewildering, and vowed not to let anyone talk me into such a nonsensical hype. It made me uneasy that we have apparently reached a stage where we would pay $60 for a device to control something we should be able to control ourselves. We’re turning to a quick technological fix for a deeper problem created by technology, we’re buying a digital product to live less digitally, and we’re paying to escape social media through a device sold to us via targeted advertising on the very platforms we are trying to escape.

In China, superapps combine payment, utility, social, news, and e-commerce functions under one umbrella, making the Dutch “Tap Out” a product that would make little sense for the Chinese market — blocking yourself from WeChat would effectively mean locking yourself out of your phone and your wallet. Yet so-called temporary “mobile self-control tools” (手机自律神器) are still quite popular on Taobao these days, typically in the form of phone lockboxes with time-lock codes, mostly to help teenagers and students focus on their studies.

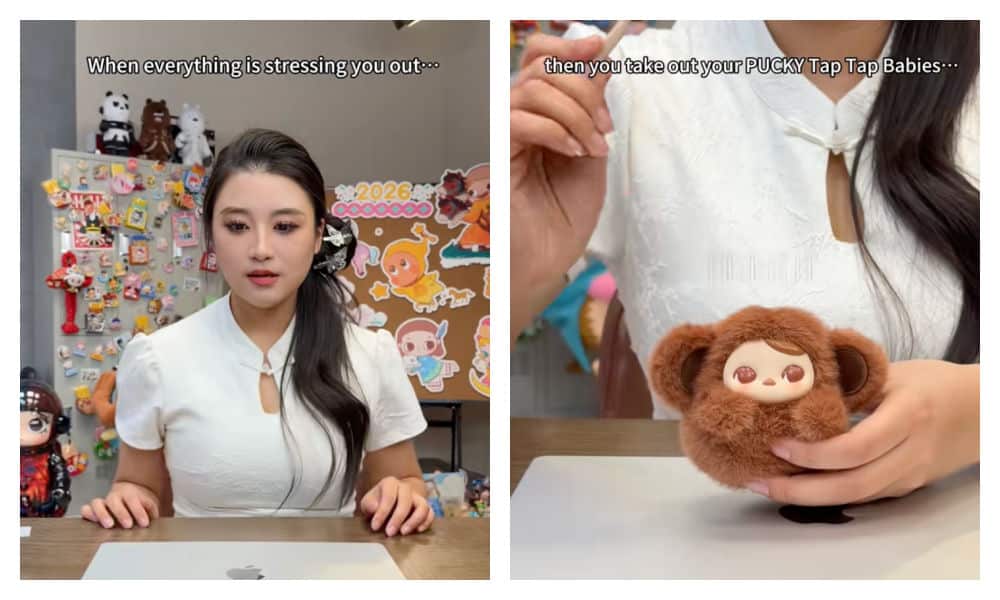

My friends in Beijing, however, were not discussing those tools. Earlier this month, instead, a photo of a fluffy toy with a cute face appeared in our WeChat group. Now that the success of Labubu is cooling down, the Pop Mart company has introduced another collectible blind-box toy: the “Pucky Tap Tap” series (PUCKY敲敲系列), also dubbed diànzǐ mùyú (电子木鱼), literally meaning “electronic wooden fish.”

A toy within the Pucky Tap Tap series.

The toy has nothing to do with actual fish, nor is it made from wood. A mùyú (木鱼) is a traditional percussion instrument, often carved from a single piece of wood and shaped like a fish. It is used in Buddhism during chanting, sutra recitation, or meditation to maintain rhythm, stay focused, and calm the mind.

The traditional muyu sold on Taobao and Amazon.

Although the Pucky Tap Tap series is inspired by the mùyú, it is essentially a battery-powered plush keychain that makes a soothing sound when you tap its head. The Pucky Tap Tap has become hugely popular as a stress-relief tool among young Chinese consumers who believe the sound can quickly ease anxiety.

On apps like Xiaohongshu, videos show people frantically tapping the toy’s head, while an official Pop Mart ad features a young woman whispering a small prayer before tapping for good luck. Another video shows a girl shutting her laptop to take a breather and tap her toy.

Video promoting the Pucky Tap Tap on Tiktok by Popmart US shop.

Some consider the toy tacky, but by now the keychain has become so wanted that resellers are asking more than double the original price, even helping to lift Pop Mart’s stock.

Another nonsensical hype, perhaps — tempting consumers to buy things they do not need by creating the illusion that peace of mind and happiness are products you can buy. A peaceful mind cannot be bought, though. It comes from within, and will not be attained through a $60 limestone “Tap Out,” nor a $25 Pop Mart “Pucky Tap Tap.” Since when did we all become so silly?

The only reason I ended up purchasing the Pucky Tap Tap is simple: it looks cute. And I am researching these trends for my work, am I not? Don’t mind me if I occasionally tap its head — just for fun. Or perhaps because it feels good to tap something other than a screen. And who knows, while I’m at it, it might bring me some good luck too. It is very different from “tapping out,” right?

Right?

Let’s dive into some of the other trends that have been especially noteworthy.

Quick Scroll

-

- 🚧 A road construction project in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, has been halted after workers uncovered ruins dating back approximately 6000-7000 years. These are now the oldest known archaeological remains in the lower Yangtze region. The discovery rewrites the entire timeline of prehistoric civilization in the region, pushing it back by more than a 1000 years.

- 👶 “Is it worth spending the best 20 years of your life raising kids?” This ad on the back of a Shenzhen bus, part of a district-level campaign on marriage and child-rearing, raised eyebrows online. While it was likely meant to spark honest reflection on parenthood, it offered a rare contrast to the messaging typically seen in Chinese official communication encouraging people to have (more) children.

- 🚗 China is set to end the era of hidden door handles. Cars with concealed handles are popular in China, where EV makers have followed design trends popularized by Tesla. But amid growing safety concerns, including cases in which car doors couldn’t be opened in emergencies, China will now become the world’s first country to mandate mechanical backup systems for car door handles and ban fully hidden ones. The new standard will take effect on January 1, 2027.

- 🐆 The snow leopard in northwest China that recently mauled a tourist who approached it for a photo has now been captured, after it entered a local herder’s sheep pen and killed 35 sheep. The animal is now held at a wildlife rescue center and is expected to be released back into the wild once the weather warms and a scientific assessment is completed.

- 🎬 After 46 years, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining made its debut on the Chinese mainland. Its first-ever theatrical release in China came just before the busy Spring Festival movie season, showing that old Hollywood classics can still draw new audiences (although not in their fully original form, as some scenes were still censored for violence).

- 🐍 Former Zhejiang Party Secretary Yi Lianhong (易炼红) is under investigation for suspected “serious violations of discipline and law.” This news comes about 2 weeks after probes into Zhang Youxia (张又侠) and Liu Zhenli (刘振立). Different roles (top military leadership vs. provincial governance), but together they point to an unusually aggressive purge cycle ahead of the 21st Party Congress. Some are calling Yi “the last tiger of the Snake Year.”

- x🎮 Time to start looking forward to Black Myth: Zhongkui (黑神话:钟馗), the sequel to Black Myth: Wukong (黑神话:悟空), the game that became a global sensation in 2024. Game Science, the Hangzhou-based studio behind the game, has just released a Chinese New Year trailer (link), offering a peek at the stunning visuals, colors, music, and narrative elements rooted in Chinese folklore.

What Really Stood Out This Week

Takaichi’s Win Seen from China: “A More Dangerous Japan”

Cartoon “Japan’s right wing on the rise” by Jin Ding 金鼎, China Daily. Feb 10, 2026.

After winning the Liberal Democratic Party leadership election in October, conservative politician and Shinzo Abe protégé Sanae Takaichi (高市早苗, in Chinese: Gāoshì Zǎomiáo) went on to secure a decisive victory in Japan’s lower house elections on Sunday, winning more than two-thirds of the seats in the snap election she called in January.

Sino-Japanese relations were a central theme in the campaign, as Takaichi’s leadership since October has already triggered one of the sharpest deteriorations in bilateral ties in recent years. This is not only due to her hardline stance on sensitive issues such as wartime history, but also because of her remarks in November on the possibility of military intervention in Taiwan-related matters. Those comments have had far-reaching consequences, ranging from import bans to Japanese performers seeing their China shows canceled.

Rather than weakening Takaichi, China’s pressure campaign appears to have boosted her popularity at home. She is not only the country’s first female prime minister, but it is also the first time the LDP — or any party in Japan, for that matter — has won such a large majority of the vote.

In China, the official response stressed that “the election is Japan’s internal affair” (“日本内政”), but reactions in state media and on social media told a different story. One general view on Takaichi’s win on Chinese social media is that it aligns with an overall decline of the center-left and a growing populism in Western societies.

Takaichi’s victory has been widely framed as a risky gamble, and her post-election comments about a possible visit to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine, where Japan’s war dead (including Class-A war criminals) are honored, further fueled online discussions portraying her not only as a threat to Sino-Japanese relations but also as a danger to Japan itself.

A political cartoon published by China Daily, in both its Chinese and international editions, depicts Takaichi rising above a field of graves belonging to war criminals, emphasizing how important wartime memory is in China’s official framing of her election win (see featured image).

From China’s perspective, Japan is a country that has never really reflected on its wartime aggressions, and Takaichi is viewed as particularly problematic in this regard for her previous remarks not just on Yasukuni, but also on other war-related topics, including denial of the comfort women issue and skepticism regarding the death toll of the Nanjing Massacre.

According to Niu Tanqin (牛弹琴), a Chinese veteran media commentator who posted on Zhihu, there are multiple risks associated with Takaichi’s win. Niu writes:

“Japan is no longer the Japan of the past. With an absolute two-thirds majority in the lower house, Takaichi has crossed the threshold required for constitutional revision. It cannot be ruled out that she may push to amend the pacifist constitution, transform the Self-Defense Forces into a “national defense army,” and accelerate Japan’s so-called “national normalization.””

“There are hidden dangers behind this path towards “normalization” for a country that has not fully reckoned with its history. Large-scale military expansion, sharply increased defense spending, and pursuit of offensive weapons may follow. It cannot be ruled out that Japan could abandon its “Three Non-Nuclear Principles” and seek to acquire nuclear weapons. On the Taiwan issue, Japan may become more provocative, and China–Japan relations will become more turbulent. What we face is a more dangerous (凶险) Japan.”

An Unfortunate Olympic Bump Between a Dutch and Chinese Athlete

The Winter Olympics have been a major topic of discussion this week, with many emotional moments being highlighted in the Chinese media.

One notable example that resonated with netizens is the interview given by the 32-year-old Chinese short track speed skater Fan Kexin (范可新). Coming from an impoverished background and dedicating years of her life to succeed in skating, now competing in her fourth Winter Olympics, Fan had an breakdown moment during an interview that suggested the end of two decades of competition when she tearfully said: “Everyone can see my hair is turning white, I’ve endured until the very end” (“大家看到我的头发已经白了,我已经熬到头了”).

Fan Kexin in her tearful interview with CCTV.

Another emotional incident specifically stood out. It was the dramatic moment during Wednesday’s men’s 1000 meter involving Dutch skater Joep Wennemars and China’s Lian Ziwen (廉子文). During the final lane change, Lian tangled with Wennemars even though the Dutch athlete, coming from the outside lane, had right of way during the exchange. The collision effectively ruined Wennemars’ medal chances. After reviewing the incident, officials disqualified the Chinese skater. Wennemars was given a re-skate thirty minutes later, but the fatigued and frustrated skater only recorded the ninth fastest time.

Lian Ziwen apologized to Joep Wennemars after the incident, according to his coach Jan Bos, who spoke to the Dutch press. Ziwen was reportedly devastated after his mistake and, according to Bos, “just cried” following his disqualification.

The topic became a major subject of discussion on Chinese social media and ranked number one on Kuaishou’s trending lists. What stands out in Chinese online reactions is that, although almost everyone seems to agree there was no intent involved, opinions clearly fall into three camps.

The first camp (most dominant) defends Lian and focuses mainly on the actions of an angry Wennemars after the finish, as the Dutch skater could be seen shouting at Lian and lashing out in his direction. In these reactions, Wennemars is insulted as an “uncivilized Dutch milk cow” or a “white pig” (or “Dutch pig”, which also means “guinea pig” in Chinese), and his reaction is framed as “anti-Chinese,” with the Nexperia affair being frequently mentioned. In these discussions, the Olympic moment takes on a clear nationalist tone and becomes symbolic of Dutch-Chinese relations at large.

The second camp views the situation primarily from an Olympic and sporting perspective and shows more understanding for Wennemars’ intense emotions. They consider Lian’s apology logical and Joep’s anger understandable. Some Douyin commenters wrote: “If you do something wrong, you should apologize. That the other person does not forgive you is perfectly normal,” and: “Whether intentional or not, four years of preparation were destroyed in an instant.” Some draw comparisons to a well-known Olympic incident in 1992, when Chinese skater Ye Qiaobo (叶乔波) also missed out on gold after being hindered by a Soviet skater during a lane change.

The third camp, a smaller but notable group, uses the discussion as a moment of reflection on Chinese social media itself, particularly on cyber-nationalism and the double standards of some internet users. As one Douyin comment put it: “When a foreigner commits a foul, people immediately start cursing. But when our own athlete makes a mistake, the foreigner gets blamed instead. That is how distorted it can be.”

An interesting detail: on Weibo, comment sections under some news posts about this incident appear to be heavily filtered. Possibly, too much geopolitics was beginning to overshadow the Olympic mood.

On the Feed

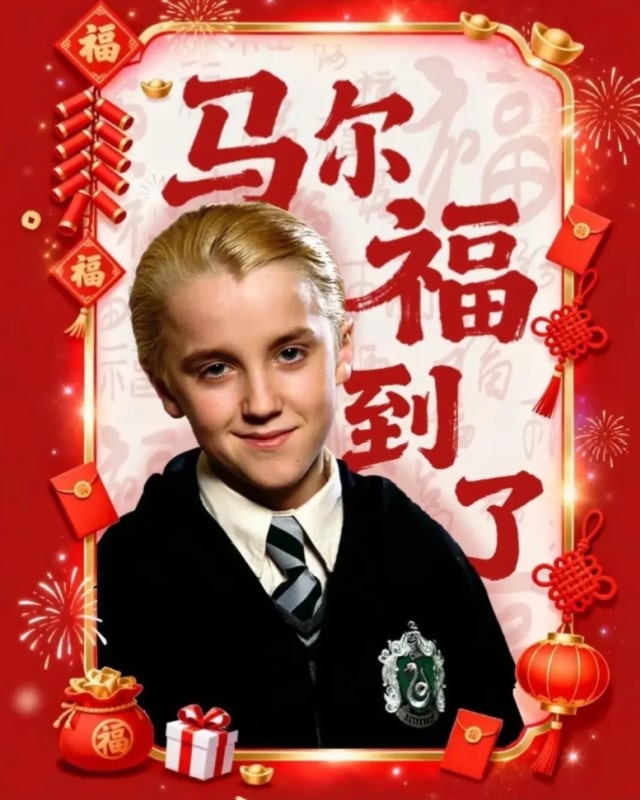

Draco Malfoy as the Lucky Chinese New Year Charm

The Year of the Horse is almost here, and celebrating the new year comes with a lot of red, a lot of ornaments, and a lot of lucky language. This year, it all came together in some surprising Spring Festival celebratory decorations focused on Draco Malfoy, the fictional villainous character from the Harry Potter series, which is also popular in China.

Malfoy in Chinese is phonetically rendered as Mǎ’ěrfú (马尔福), containing the characters 马 meaning “horse” and 福 meaning “luck” or “good fortune.” With Malfoy’s name thus associated with good luck in the new year, decorations featuring his face have shown up on front door banners and fridge magnets.

By now, the original lucky decorations have been picked up by international media, and Tom Felton, the actor who plays Malfoy in the movies, is now also more than aware that he became the most unexpected mascot of the Chinese New Year , as he himself reposted an image that highlighted his new status.

Seen Elsewhere

• In a China where pursuing an abundant career and life in the city has become increasingly competitive and stressful, embracing “ugly things” sparks empathy, humor, and nostalgia for simpler times. (BAIGUAN)

• Anti-Chinese sentiments are on the rise in South Korea. What makes the current wave of Sinophobia in South Korea different is not just its intensity, but the social media infrastructure through which it circulates. (THE DIPLOMAT)

• One year ago, an American couple discovered a peculiar typewriter in boxes cleared out from an Arizona basement. They later discovered that it was the long-lost prototype of the MingKwai typewriter, an invention that fundamentally redefined the logic of typing Chinese characters. (SIXTH TONE)

• Their most intimate moments had been captured by a camera hidden in their Chinese hotel room, and then “Eric” found out that the footage was made available to thousands of strangers when he logged in to watch p*rnography on the very same channel he was exposed in. (BBC)

—That’s a wrap. Keep an eye on the next newsletter, which will be all about the Chinese New Year!

See you next edition.

Best,

Manya

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo. Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. If you no longer wish to receive these newsletters, or are receiving duplicate editions, you can unsubscribe at any time.

Chapter Dive

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

A virtual Viagra for a pressured generation? The real story behind China’s latest viral app.

Published

1 month agoon

January 14, 2026

From censored joke to state-friendly app, ‘Are You Dead Yet?’ has traveled a long road before reaching the top of China’s paid app charts this week. While marketed as a tool for those living alone to check in with emergency contacts, the app’s viral success actually isn’t all about its features.

It is undoubtedly the most unexpected app to go viral in 2026, and the year has only just started. “Are You Dead?” or “Dead Yet?” (死了么, Sǐleme) is the name of the daily check-in app that surged to the No. 1 spot on Apple’s paid app chart in China on January 10–11, quickly becoming a widely discussed topic on Chinese social media. It has since become a top-searched topic on the Q&A platform Zhihu and beyond, and by now, you may even have noticed it appearing on your local news website.

For many Chinese who first encountered the app, its name caused unease. In China, casually invoking words associated with death is generally considered taboo, seen as causing bad luck. It was therefore especially noteworthy to see state media outlets covering the trend. The fact that the name plays on China’s popular food delivery platform Ele.me (饿了么, “Hungry Yet?”), a household name, may also have softened the linguistic sensitivity.

Beyond the name, attention soon shifted to the broader social undercurrents and collective anxieties reflected in the app’s sudden popularity.

🔹 “A More Reassuring Solo Living Experience”

Are You Dead Yet? is a basic app designed as a safety tool for people living alone, allowing them to “check in” with loved ones. The Chinese app has been available on Apple’s App Store since 2025 and currently costs 8 yuan (US$1.15) to download.

The app is very straightforward and does not require registration or login. Users simply enter their name and an emergency contact’s email address. Each day, they tap a button to virtually “check in.”

If a user fails to check in for two consecutive days, the system automatically sends an email notification to the designated emergency contact the following day, prompting them to check on the user’s safety.

The app was created by Guo Mengchu (郭孟初) and two of his Gen Z friends from Zhengzhou, all born after 1995. Together, they founded the company Moonlight Technology (月境技术服务有限公司) in March 2025, with a registered capital of 100,000 yuan (US$14,300). The app was reportedly developed in just a few weeks at a cost of approximately 1,000 yuan (around US$143).

In the text introducing the Dead Yet? app, the makers write that the app is specifically intended to “build seamless security protection for a more reassuring solo living experience” (“构建无感化安全防护,让独处生活更安心”).

🔹 The Rise of China’s Solo-Living Households

The number of solo households in China has skyrocketed over the past three decades. In the mid-1990s, only 5.9% of households in China were one-person households. By 2011, that number had nearly tripled from 19 million to 59 million, accounting for nearly 15% of China’s households.1,2 By now, the number is bigger than ever: single-person households account for over 25% of all family households.3

These roughly 125 million single-person households are partly the result of China’s rapidly aging society, along with its one-child policy. With longer life expectancies and record-low birth rates, more elderly people, especially widowed women, are living alone without their (grand)children.

China’s massive urban-rural migration, along with housing reforms that have adapted to solo-living preferences, has also contributed to the fact that China is now seeing more one-person households than ever before. By 2030, the number may exceed 150 million.

But other demographic shifts play an increasingly important role: Chinese adults are postponing marriage or not getting married at all, while divorce rates are rising. Over the past few years, Chinese authorities have introduced various measures to encourage marriage and childbirth, from relaxed registration rules to offering benefits, yet a definitive solution to combat China’s declining birth rates remains elusive.

🔹 A “Lonely Death”: Kodokushi in China

Especially for China’s post-90s generation, remaining unmarried and childless is often a personal choice. On apps like Xiaohongshu, you’ll find hundreds of posts about single lifestyles, embracing solitude (享受孤独感), and “anti-marriage ideology” (不婚主义). (A few years back, feminist online movements promoting such lifestyles actually saw a major crackdown.)

Although there are clear advantages to solo living—for both younger people and the elderly—there are also definite downsides. Chinese adults who live alone are more likely to feel lonely and less satisfied with their lives 4, especially in a social context that strongly prioritizes family.

Closely tied to this loneliness are concerns about dying alone.

In Japan, where this issue has drawn attention since the 1990s, there is a term for it: kodokushi (孤独死), pronounced in Chinese as gūdúsǐ. Over the years, several cases of people dying alone in their apartments have triggered broader social anxiety around this idea of a “lonely death.”

One case that received major attention in 2024 involved a 33-year-old woman from a small village in Ningxia who died alone in her studio apartment in Xianyang. She had been studying for civil service exams and relied on family support for rent and food. Her body was not discovered for a long time, and by the time it was found, it had decomposed to the point of being unrecognizable.

Another case occurred in Shanghai in 2025. When a 46-year-old woman who lived alone passed away, the neighborhood committee was unable to locate any heirs or anyone to handle her posthumous affairs. The story prompted media coverage on how such situations are dealt with, but it drew particular attention because cases like this had previously been rare, stirring a sense of broader social unease.

🔹 The Sensitive Origins of “Dead Yet?”

Knowing all this, is there actually a practical need for an app like Dead Yet? in China? Not really.

China has a thriving online environment, and its most popular social media apps are used daily by people of all ages and backgrounds, across urban and rural areas alike. There are already countless ways to stay in touch. WeChat alone has 1.37 billion monthly active users. In theory (even for seniors) sending a simple thumbs-up emoji to an emergency contact would be just as easy as clocking in to the Dead Yet? app.

The app’s viral success, then, is not really about its functionality. Nor is it primarily about elderly people fearing a lonesome death. Instead, it speaks to the dark humor of younger adults who feel overwhelmed by pressure, social anxiety, and a pervasive sense of being unseen—so much so that they half-jokingly wonder whether anyone would even notice if they collapsed amid demanding work cultures and family expectations.

And this idea is not new.

After some online digging, I found that the app’s name had already gone viral more than two years earlier.

That earlier viral moment began with a Zhihu post titled “If you don’t get married and don’t have children, what happens if you die at home in old age?” (“不结婚不生孩子,老后死在家中怎么办”). Among the 1,595 replies, the top commenter, Xue Wen Feng Luo (雪吻枫落), whose response received 8,007 likes, wrote:

💬 “You could develop an app called “Dead Yet?” (死了么). One click to have someone come collect the body and handle the funeral arrangements.”

The original post that started it all. That humorous comment was the initial play on words linked to food delivery app Eleme (饿了么).

Two days later, on October 8, 2023, comedy creator Li Songyu (李松宇, @摆货小天才), also part of the post-90s generation, released a video responding to the comment.

In it, he presented a mock version of the app on his phone: its logo a small ghost vaguely resembling the Ele.me icon, and its interface showing some similarities to ride-hailing apps like Uber or Didi.

In the video, Li says:

🗯️ “Are You Dead Yet?’ I’ve already designed the app for you. (…) The app is linked to your smart bracelet. Once it fails to detect the user’s pulse, someone will immediately come to collect the body. Humanized service. You can choose your preferred helper for your final crossing, personalize the background music for cremation and burial, and even set the furnace temperature so you can enter the oven with peace of mind. Big-data matching is used to connect people who might have known each other in life, followed by AI-assisted cemetery matching for the afterlife traffic ecosystem—you’ll never feel alone again. After burial, all content on your phone is automatically formatted to protect user privacy and eliminate worries about what comes after. There’s a seven-day no-reason refund, almost zero negative reviews, and even an ‘Afterlife Package’ with installment payments. Invite friends to visit the grave and have them help repay the debt. And if not everything turns to ashes properly, or if you’re dissatisfied with the shape of the remains, you can invite friends to burn them again and get the second headstone at half price! How about that? Tempted?”

The original “Sileme” or “Dead Yet” app idea, October 2023.

The video went viral, drew media coverage (one report called the concept and design of the “Are You Dead?” app “unprecedented”), and sparked widespread discussion. Although viewers clearly understood that the idea—one click and someone arrives to collect the body and arrange the funeral—was a joke, it nevertheless struck a chord.

Many saw the video as a glimpse into China’s future, arguing that with extremely low birth rates and a rapidly aging society, such business ideas might one day become feasible. Some people pointed to Japan’s growing problem of elderly people dying alone, suggesting that China may come to face similar challenges. At the same time, it also sparked concerns about increasing social isolation.

Despite its popularity, both the video and the trending hashtag “Dead Yet App” (#死了么APP#) were taken offline. A comedy podcast episode discussing the concept—“Did Someone Really Create the ‘Dead Yet’ App?” (真的有人做出了“死了么”APP?), released on October 10, 2023 by host Liuliu (主播六六)—was also removed.

According to Li Songyu himself, the video went offline within 48 hours “for reasons beyond one’s control” (“出于不可抗因素”), a phrase often used to avoid explicitly referring to top-down decisions or censorship.

It is not hard to guess why the darkly humorous Dead Yet? concept disappeared. And it wasn’t only because of crude jokes or the sensitivities surrounding death.

The video appeared less than a year after the end of China’s stringent zero-Covid policies, which had been preceded by protests. In both early and late 2023, Covid infections were widespread and hospitals were overcrowded. It was therefore a particularly sensitive moment to joke about bodies, afterlife logistics, and people being “taken away.”

Moreover, 2023 was a year in which state media strongly emphasized “positive energy,” promoting stories of heroism, self-sacrifice, and resilience in the face of hardship. It was not a time to dwell on death, and certainly not through humor.

🔹 Why a Censored Idea Became a ‘State-Friendly’ App

In 2025, things looked very different. Just weeks after the current Dead Yet? app was developed, it was released on the App Store on June 10, 2025. Not only was its name identical to the app “introduced” by Li in 2023, but its logo was also a clear lookalike.

The 2023 logo and 2025 “Dead Yet?” logo’s.

Although Li Songyu published a video this week explaining that he and his team were the original creators of the Dead Yet? concept and that they had planned to develop a real app before the idea was censored (without ever registering the trademark), app creator Guo Mengchu has simply stated that the inspiration for their app came “from the internet.”

In the same interview, Guo also emphasized that the app’s sudden rise was entirely organic, with the whole process of “going viral,” from ordinary users to content creators to mainstream media, taking about a day and a half.5

However, the app’s actual track record suggests a much bumpier journey.6 Since its launch, it has been taken down once and was reportedly removed from the App Store rankings three times. Such removals commonly occur due to suspected artificial download inflation, ranking manipulation, or other compliance-related issues.

After the most recent delisting on December 15, 2025, the app returned to the App Store on December 25—and only then did it finally have its breakthrough moment.

📌 Looking at how online discussions unfolded around the app, it becomes clear that, just as in 2023, the idea of relying on technology to ensure someone will notice if you die strongly resonates with people. Many users also seem to have downloaded it simply as a quirky app to try out. Once curiosity set in, the snowball quickly started rolling.

📌 But Chinese state media have also played a significant role in amplifying the story. Outlets ranging from Xinhua (新华) and China Daily (中国日报) to Global Times (环球时报) have all reported on the app’s rise and subsequent developments.

🔎 Why was Li Songyu’s Dead Yet? app idea not allowed to remain online, while Guo’s version has been able to thrive? The difference lies not only in timing, but also in tone. Li’s original concept leaned more clearly toward implicit social critique & satire. Guo’s app, by contrast, has been framed — and received — with far less overt sarcasm. While many netizens may still interpret it as dark humor, within official narratives it aligns more neatly with the family-focused social discourse, and perhaps even functions as an implicit warning: if you end up alone, you may literally need an app to ensure you do not die unnoticed.

In this way, the young creators of the new app are, perhaps inadvertently, contributing to an ongoing official effort in media discourse and local initiatives to encourage Chinese single adults to settle down and start a family. For them, however, it is a business opportunity: more than sixty investors have already expressed interest in the app.

Funnily enough, many single men and women actually hope to use the app to support their lifestyle. When, during the upcoming Chinese New Year, parents start nagging about when they will settle down, and warn that they might otherwise die alone, they can now reply that they’ve already got an app for that.

🔹 What’s in a Name?

Over the past few days, much of the discussion has centered on the app’s name, which is what drew attention to it in the first place. As interest in the app surged, fueled by international media coverage, criticism of the name also grew. Some found it too blunt, while public commentators such as Hu Xijin openly suggested that it be changed.

Considering that the mention of death itself carries online sensitivities in China, it’s possible that there’s been some criticism from internet regulators, and the Ele.me platform also might not be too pleased with the name’s resemblance.

Whatever the exact reasons, the app’s creators announced on January 13 that they would abandon the original name and rebrand the app as its international name ‘Demumu’ (De derived from death, the rest intentionally sounds like ‘Labubu’).

This marked a notable shift in stance: just two days earlier, one of the app’s creators had stated that they had not received any formal requests from authorities to change the name and had shown no apparent intention of doing so.

Most commenters felt that without the original name, the app doesn’t make sense. “As young people, we don’t care so much about taboo words,” one commenter wrote: “Without this name, the app’s hype will be over.”

On January 14, the creators then made another U-turn and invited app users to think of a new name themselves, rewarding the first user who proposes the chosen name with a 666 yuan reward ($95).

The naming hurdles suggest the makers are quite overwhelmed by all the attention. At the same time, dozens of competing apps have already appeared. One of them, launched just a day after Are You Dead Yet? went viral, is “Are You Still Alive?” (活了么), which offers similar basic functions but is free.

This new wave of similar apps has also led more people to wonder how effective these tools really are once the quirkiness wears off. One Weibo blogger wrote:

💬 “I really don’t understand why this app went viral. You can only check in daily, and you need to miss two consecutive check-in days for the emergency contact to be alerted. That means, if something actually happens, someone will only come after three days!! You’ll be rotting away in your home!!”

Others also suggested that it is clear the app was designed by younger people—the elderly users who might need it most would likely forget to check in on a daily basis.

🔹 Why “Dead Yet?” Is Like Viagra for a Pressured Generation

Amid the flood of Chinese media coverage, one commentary by the Chinese media platform Yicai7 stands out for pinpointing what truly lies behind the app’s popularity.

The author of the piece “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Dead Yet’ App” (in Chinese) argues that the app did not win users over because of its practical utility. Its main users are young people for whom premature death is an extremely low-probability event. They are clearly not downloading the app because they genuinely fear that “no one would know if they died,” nor are they likely to check in daily for such a tiny risk.

Since the app is clearly being embraced by users that do not belong to the actual target group, it must be providing some unexpected value.

💊 The author compares this unplanned function of the app to how Viagra was originally developed to treat heart disease. In this case, app users say that interacting with Dead Yet? feels like a lighthearted joke shared between close friends, offering a sense of social empathy and emotional release in a way that does not feel pressured.

Because the pressure—that’s the problem. Yicai describes just how multidimensional the pressures facing many young adults in China today can be: there is the economic challenge of the never-ending rat race dubbed “involution” along with uncertainty in the job market; there’s the “996” extreme work culture across various industries, leaving little room for private life; traditional family expectations that clash with housing and childcare costs that many find unattainable; and the world of WeChat and other social media, which can further intensify peer pressure and anxiety.

Of course, a lot has been written about these issues through the years. But do people really get it?

According to Yicai, there’s not enough understanding or support for the kinds of challenges young people face in China today. Even worse, older generations’ own past experiences often impose additional burdens on younger people, who keep running up against traditional notions while receiving inadequate support in areas such as education, employment, housing, marriage, family life, and even healthcare.

The author describes the unexpected viral success of Dead Yet? as a mirror with a message:

💬 “The viral popularity of ‘Are You Dead?’ seems like a darkly humorous social metaphor, reminding us to pay attention to the living conditions and inner worlds of today’s youth. For the young people downloading the app, what they need clearly isn’t a functional safety application, it’s a signal that what they really need is to be seen and to be understood—a warm embrace from society.”

Will the Dead Yet? app survive its name change? Is there a future for Demumu, or whatever it will end up being called? As it is now—the basic app with check-in and email or SMS functions—it might not keep thriving beyond the hype. If it doesn’t, it has at least already fulfilled an important function: showing us that in a highly digitalized, stressful, and often isolating society where AI and social media play an increasingly major role, many people yearn for the simple reassurance of being noticed, mixed with a shared delight in dark humor. Just a little light to shine on us, to remind us that we’re not dead yet.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Thanks to Ruixin Zhang & Miranda Barnes for additional research

1 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2013. “Living Alone in China: Historical Trends, Spatial Distribution, and Determinants.”

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Living-Alone-in-China-%3A-Historical-trend-%2C-Spatial-Yeung-Cheung/8df22ddeb54258d893ad4702124066b241bbdf8d.

2 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2015. “Temporal-Spatial Patterns of One-Person Households in China, 1982–2005.” Demographic Research 32: 1103–1134.

3 Li Jinlei (李金磊). 2022. “China’s One-Person Households Exceed 125 Million: Why Are More People Living Alone?”[中国新观察|中国一人户数量超1.25亿!独居者为何越来越多?]. China News Service (中国新闻网), January 14, 2022. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cj/2022/01-14/9652147.shtml (accessed January 13, 2026).

4 Danan Gu, Qiushi Feng, and Wei-Jun Jean Yeung. 2019. “Reciprocal Dynamics of Solo Living and Health Among Older Adults in Contemporary China.”

The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 74 (8): 1441–1452. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby140.

5 Wang Fang (王方). 2026. “‘How We Went Viral: The Founder of the ‘Dead Yet?’ App Speaks Out’” [‘死了么’创始人亲述:我们是如何爆红的]. Pencil Way (铅笔道), interview with Guo (郭先生), published via 36Kr (36氪), January 13, 2026. https://www.36kr.com/p/3637294130922754 (accessed January 13, 2026).

6 Lü Qian (吕倩). 2026. “‘Am I Dead?’ App Price Raised from 1 Yuan to 8 Yuan, Previously Removed from Apple App Store Rankings Multiple Times”

[‘死了么从一元涨至八元,曾被苹果AppStore多次清榜’]. Diyi Caijing (第一财经), January 11, 2026. https://www.yicai.com/news/102997938.html (accessed January 14, 2026).

7 First Financial/Yicai (第一财经). 2026. “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Am I Dead?’ App: Young People Need a Hug” [‘死了么爆火背后,年轻人需要一个拥抱’]. Official account article, January 12, 2026. https://www.toutiao.com/article/7594671238464569899/ (accessed January 14, 2026).

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West