China ACG Culture

Rotten Girls: China’s Thriving Online Boys’ Love Culture

It is an online subculture that has been around for more than a decade, and it is not likely to die out any time soon.

Published

5 years agoon

They are mocked, hated, and misunderstood, yet China’s so-called ‘Rotten Girls’ are at the core of an online subculture that has been thriving for years.

This is the “WE…WEI…WHAT?” column by Manya Koetse, original publication in German by Goethe Institut China (forthcoming), see Goethe.de: WE…WEI…WHAT? Manya Koetse erklärt das chinesische Internet.

China’s ever-buzzing social media sphere sees trends, topics, and movements pop up every single day and then fade away quickly when their novelty is gone. But there are some trends that turn into something bigger, bringing forth communities and online subcultures that keep on thriving for years, with the participants building their own spaces in the online environment.

One such space belongs to those who, with some self-mockery, define as “Rotten Girls” (fǔnǚ 腐女), derived from the Japanese fujoshi. In the Chinese context, ‘Rotten Girls’ are young women with a passion for fictional stories, drama series, and manga (comic books) featuring gay male erotica and romantic relationships called ‘yaoi.’

‘Rotten girls’ do not just consume these stories, primarily written by and for women, they also create and share them with others to discuss.

In Chinese, the gay erotica known as yaoi is also called ‘danmei’ (耽美) or ‘BL’ (for ‘Boys’ Love’) – all umbrella terms for contents of male-male homoerotic fiction. The genre plays a major role in various corners of the Chinese internet. It is an online subculture that has been around for more than a decade, and it is not likely to die out any time soon.

Media and technology both play a big part in the sharing of fǔnǚ fantasies. These fantasies can range from boys holding hands to more pornographic ones, but the main point of the imaginary is love and intimacy (Galbraith 2011, 213).

Always Another BL Trend

There is always something different trending in the world of Rotten Girls. This summer, for example, the release of the Japanese 18+ games ‘Lkyt’ by BL game brand Parade received a lot of attention. A previous game by Parade, ‘Room No. 9,’ is also still popular among BL fans in China. The game revolves around two young men, long-time friends, who get locked inside a room where they are subjected to a behavioral analysis experiment. The two have to make some taunting decisions, including possibly being forced into sexual activity with each other, in order to make it out alive.

Another major topic that went trending within the Rotten Girls community some years ago, even attracting the attention of western news media, was the British crime drama Sherlock. Many Chinese viewers in the BL scenes were convinced that detective Sherlock Holmes (played by Benedict Cumberbatch) and his sidekick Watson (Martin Freeman) were not just professional partners, but a romantic couple. This practice of imagining a relationship between two characters is also known as ‘CP,’ an abbreviation for “coupling” or “character pairing.”

The ambiguous relationship between Holmes and Watson – and the very fact that they are not explicitly homosexual – suits the fantasies harbored by China’s fǔnǚ. There are countless examples of how BL fans photoshopped Sherlock images into homoerotic scenes, making up their own stories and endlessly discussing the relationship between Holmes and Watson.

Fanart: Holmes and Watson share a passionate kiss

BL fans are active in various online spaces. There are Rotten Girls communities on Chinese literature websites, discussion boards, and on ACG-focused platforms such as Bilibili (ACG is a popular abbreviation of “Anime, Comic and Games”). Boys’ Love is practically everywhere: short stories, web novels, manga, anime, games, and series are all actively created, consumed, and shared within the BL fandom.

The Chinese Jinjiang Literature City site (1998) is one of the earliest and most influential websites for the danmei genre, where some top channels receive millions of clicks. The Chinese web novel author ‘Priest’ is among one of the most successful authors (some translations in English can be found here).

But besides the special BL fiction forums, there are also many fǔnǚ accounts on the more mainstream social media platforms such as WeChat and Weibo. Under Weibo hashtags such as “Fǔnǚ Daily” (#腐女日常#), “BL Webtoons” (#bl条漫#), “BL Manga” (#bl漫画#), “Original Danmei” (#原创耽美#), and many more, Rotten Girls discuss their favorite danmei works and the latest news on a daily basis.

Although the Rotten Girls have been increasing their sphere of influence, it hasn’t been without controversy. Not only are they often looked down upon for their love for male homoeroticism, some LGBT people also criticize them for silencing the voices of actual gay men or erasing real-life gay experiences.

From Japanese Toy Boys to Chinese Danmei

Where did this all begin? China’s BL subculture finds it roots in Japan. The popularity of danmei came up with the growing influence of Japanese popular culture in China.

In the early 1990s, Japanese manga and anime titles started flooding the Chinese market, often as unauthorized (pirated) copies. With this wave of Japanese entertainment products hitting the Chinese market, there were also those belonging to the genre of BL.

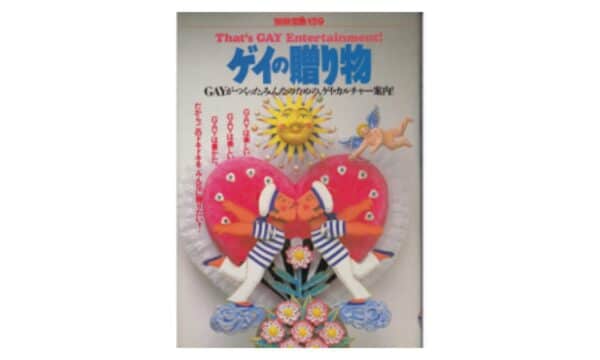

In Japanese fiction and manga, the theme of male-male romance intended for a female audience emerged as early as the 1970s but did not really rise to popularity until the early 1990s, when Japanese mainstream media saw a ‘gay boom’ and representations of male homosexuality became in vogue.

The year 1993 truly was a ‘gay year’ in the Japanese media and entertainment industry. In “Producing Gayness” (1997), Sho Ogawa describes how one Japanese magazine even offered readers a “Gay Toybox”: full color paper gay dolls to cut out, including matching clothes from jackets to sports uniforms and even leather bondage gear. Instructions that came with the paper dolls encouraged readers to play with them, “give them a lovely name” and “imagine a campus love affair” between them.

It was also in this same year of 1993 that many Chinese young women first discovered the genre of Japanese Boys’ Love, mainly through the dissemination of pirate manga, novels, and magazines in Chinese bookstores.

Throughout the years, the Chinese genre of danmei has become much more than just an imported entertainment genre from Japan, and it is also somewhat different from the subgenre of ‘slash fiction’ in the West.

Danmei literally means “to indulge in beauty,” and it has developed its own characteristics, taking a predominantly literary form while also strongly resonating with Japanese visual culture (Madill et al 2018, 5). Since the first Chinese BL-focused monthly magazine appeared in 1999, the genre has mixed with various local and other foreign media and celebrity cultures (e.g. that of South Korean and Thailand), and has become a truly Chinese fan culture phenomenon (Chen 2017, 7; Yang & Xu 2017, 3).

Safe, Subversive, and Pure Love

Those outside the danmei subculture often wonder what makes ‘Boys’ Love’ so appealing to so many young women. There are various explanations and interpretations of why female fans enjoy writing and reading about male homoeroticism.

Chen Xin, who studied the topic of Boys’ Love at the University of British Columbia, offers “safety” as one explanation for the popularity of danmei, as it gives its readers, mostly straight women, the freedom to fantasize in a way that is removed from their own romantic lives. This is also reiterated by other scholars, who argue that BL provides a safe fantasy where female fans can avoid the objectification of women while exploring the boundaries of their own sexuality.

The concept of ‘pure love’ is one of the funü’s greatest attraction to BL. According to them, it is the most romantic type of love because it transcends the boundaries of gender. The male protagonists in these stories do not identify as gay, but fall in love with other men nevertheless. “It doesn’t matter if you are male or female, I just love you” and “It’s not that I am gay, I just love a man” are classic sentences within Rotten Girls’ fiction (Dai 2013, 34).

Zhang Chunyu (2016) also highlights the genre as an outlet for female writers and readers to explore sexuality and pleasure in a “subversive” way. Rotten girls position males as the objects of female desire, and in doing so, they challenge traditional gender stereotypes and appreciate gender fluidity.

China’s Rotten Girls subculture is also ‘subversive’ in another way. Because of its focus on homosexuality and eroticism, danmei fandom is subject to online censorship. According to China’s cyberspace regulations, online content should adhere to the “correct political direction” and “strive to disseminate contemporary Chinese values.” Over the past few years, there have been various moments when displays of homosexuality were targeted by censors.

An anti-pornography campaign of 2014 resulted in the shutdown of hundreds of websites and social media accounts. Throughout the years, dozens of danmei authors have been arrested and many sites were closed or deleted for creating and distributing homoerotic content (Chen 2017, 9; Madill et al 2018, 6; Zhang 2016, 250).

Despite the strict internet control, fǔnǚ and BL content are still going strong. In order to circumvent censorship, the words and images used are often coded or nuanced enough not to get deleted – but BL fans will still understand and enjoy the subtext.

Over the past years, China’s Rotten Girls have grown from a niche community to a force to reckon with on the Chinese internet. They have become a phenomenon that is often discussed in the media and is even researched by many academics.

“We’ve become professionals now,” one ‘Rotten Girl’ joked on Weibo recently.

Another commenter replied that the rise and possible fall of the danmei community is, eventually, intrinsically linked to how much room is given by China’s internet regulators. Although the past decade has demonstrated that Rotten Girls are not easily scared away by censorship and shutdowns, their future eventually does depend on the online accessibility to BL media and forums.

“If there is no relaxed online environment, it doesn’t matter how professional we are,” one commenter writes: “We might come to a standstill.”

What the future will hold for China’s Rotten Girls remains to be seen. Whether met with controversy or censorship, for now it seems impossible to put the Rotten Girls back into the closet they came from.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

This text was written for Goethe-Institut China under a CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE license (Creative Commons) as part of a monthly column in collaboration with What’s On Weibo.

References

Chen, Xin. 2017. “Boys’ Love (Danmei) Fiction On The Chinese Internet: Wasabi Kun, The Bl Forum Young Nobleman Changpei, And The Development Of An Online Literary Phenomenon.” MA Thesis, University of British Colombia https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Boys%27-Love-(Danmei)-fiction-on-the-Chinese-internet-Chen/63e7b494653bc1d849461b7a8f3d57aad05be452 [Aug 30, 2020].

Cohane (阿扣-绝赞爬墙中). 2020. “第二章 中国内地BL文化发展历史整理 [Part Two: A History of Development of Mainland China BL Culture Development]” (In Chinese). Weibo Article, Aug 8, https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309404536531036799045 [Aug 26 2020].

Dai, Fei 戴非. 2013. “腐女心理 [Funu Psychology]” (In Chinese). 大众心里学 Popular Psychology (12): 34-35.

Galbraith, Patrick W. 2011. “Fujoshi: Fantasy Play and Transgressive Intimacy among “Rotten Girls” in Contemporary Japan.” Signs 37 (1): 211-232.

Larigakis, Sophia. 2017. “Boys’ Love: The Gay Erotica Taking China by Storm.” Sophialarigakis.com, Nov 6 https://www.sophialarigakis.com/writing/boys-love-china [Aug 29, 2020].

Madill, A., Zhao, Y. and Fan, L. 2018. “Male-male marriage in Sinophone and Anglophone Harry Potter Danmei and Slash.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 9 (5): 418-434.

Ogawa, Sho. 2017. “Producing Gayness: The 1990s “Gay Boom” in Japanese Media.” PhD Dissertation, University of Kansas.

Yang, Ling and Yanrui Xi. 2016. “Danmei, Xianqing, and the making of a queer online public sphere in China.” Communication and the Public 1 (2): 251-256.

Yang, Ling and Yanrui Xu. 2017. “Chinese Danmei Fandom and Cultural Globalization from Below.” In: Lavin, Maud, Ling Yang, and Jing Jamie Zhao (eds). 2017. Boys’ Love, Cosplay, and Androgynous Idols – Queer Fan Cultures in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, page 3-20.

Zhang, Chunyu. 2016. “Loving Boys Twice as Much: Chinese Women’s Paradoxical Fandom of “Boys’ Love” Fiction.” Women’s Studies In Communication 39 (3): 249–267.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China ACG Culture

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

Published

8 months agoon

July 6, 2025

In our last article, we’ve determined how Wakuku’s rise is not just about copying & following in Labubu’s footsteps and more about how China is setting the pace for global pop culture IPs. I now want to give you a small peek into the main characters in the field that are currently relevant.

Even if these dolls aren’t really your thing, you’ll inevitably run into them and everything happening around them.

Before diving into the top trending characters, a quick word on the challenges ahead for Labubu & co:

🚩 Bloomberg Opinion columnist Shuli Ren recently argued that Labubu’s biggest threat isn’t competition from Wakuku or knockoffs like “Lafufu,” but the fragility of its resale ecosystem — particularly how POP MART balances supply, scarcity, and reseller control.

Scarcity is part of what makes Labubu feel premium. But if too many dolls go to scalpers, it alienates real fans. If scalpers can’t profit, Labubu risks losing its luxury edge. Managing this dynamic may be POP MART’s greatest long-term challenge.

🚩 Chinese Gen Z consumers value authenticity — and that’s something money can’t manufacture. If China’s booming IP toy industry prioritizes speed and profit over soul, the hype may die out at a certain point.

🚩 The same goes for storytelling. Characters need a solid universe to grow in. Labubu had years to build out its fantasy universe. Cute alone isn’t enough — characterless toys don’t leave a lasting impression and don’t resonate with consumers.

Examples of popularity rankings of Chinese IP toys on Xiaohongshu.

With that in mind… let’s meet the main players.

On platforms like Xiaohongshu, Douyin, and Weibo, users regularly rank the hottest collectible IPs. Based on those rankings, here’s a quick who’s-who of China’s current trend toy universe:

1. Labubu (拉布布)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Kasing Lung

Year launched: 2015 (independent), 2019 with POP MART.

The undisputed icon of China’s trend toy world, Labubu is a mischievous Nordic forest troll with big eyes, nine pointy teeth, and bunny ears. Its quirky, ugly-cute design, endless possibilities of DIY costume changes, and viral celebrity endorsements have made it a must-have collectible and a global pop culture phenomenon.

2. Wakuku (哇库库)

Brand & Creator: Letsvan, backed by QuantaSing Group

Year launched: 2024 with first blind box

Wakuku, a “tribal jungle hunter” with a cheeky grin and unibrow, is seen as the rising star in China’s trend toy market. Wakuku’s rapid rise is fueled by celebrity marketing, pop-up launches, and its strong appeal among Gen Z, especially considering Wakuku is more affordable than Labubu.

3. Molly (茉莉)

Brand: POP MART

Designer: Kenny Wong (王信明)

Year launched: 2006 (creator concept); POP MART 2014, first blind boxes in 2016

Molly is a classic trend toy IP, one of POP MART’s favorites, with a massive fanbase and long-lasting popularity. The character was allegedly inspired by a chance encounter with a determined young kid at a charity fundraiser event, after which Kenny Wong created Molly as a blue-eyed girl with short hair, a bit of a temperament, and an iconic pouting expression that never leaves her face.

4. SKULLPANDA (骷髅熊猫)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Chinese designer Xiong Miao

Year launched: 2018 (creator concept); POP MART 2020

Skullpanda is one of POP MART’s flagship IPs —it’s a goth-inspired fantasy design. According to POP MART, SKULLPANDA journeys through different worlds, taking on various personas and living out myriad lives. On this grand adventure, it’s on a quest to find its truest self and break new ground all while contemplating the shape of infinity.

5. Baby Zoraa

Brand: TNT SPACE

Creator: Wang Zequn, CEO of TNT SPACE

Year launched: 2022, same year as company launch

Baby Zoraa is cute yet devlish fierce and is one of the most popular IPs under TNT SPACE. Baby Zoraa is the sister of Boy Rayan, another popular character under the same brand. Baby Zoraa’s first blind box edition reached #1 on Tmall’s trend toy sales charts and sold over 500,000 units.

6. Dora (大表姐)

Brand: TNT SPACE

Year Launched: 2023

Dora is a cool, rebellious “big sister” figure, instantly recognizable for her bold attitude and expressive style. She’s a Gen Z favorite for her gender-fluid, empowering persona, and became a breakout sucess under TNT when it launched its bigger blind boxes in 2023.

7. Twinkle Twinkle [Star Man] (星星人)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Illustrators Daxin and Ali

Year launched: In 2024 with POP MART

This character has recently skyrocketed in popularity as a “healing star character” inspired by how stars shine even in darkness. POP MART markets this character as being full of innocence and fantasy to provide some relaxation in this modern society full of busyness and pressure.

8. Hirono (小野)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Lang

Year launched: In 2024 with POP MART

This freckled, perpetually grumpy boy has a wild spirit combining introversion and playful defiance. Hirono highlights the subtle fluctuations of life, its ups and downs, incorporating joy, sadness, fear, and more – a personification of profound human emotions.

9. Crybaby (哭娃)

Brand: POP MART

Creator: Thai artist Molly Yllom (aka Nisa “Mod” Srikamdee)

Year launched: 2017 (creator concept), 2023 POP MART launch

Like Wakuku, Crybaby suddenly went from a niche IP to a new hot trend toy in 2025. Together with Wakuku, it is called the “next Labubu.” Thai artist Molly Yllom created the character after the loss of her beloved dog. Crybaby is a symbol of emotional expression, particularly the idea that it’s okay to cry and express feelings.

10. Pouka Pouka (波卡波卡)

Brand: 52TOYS

Creator: Ma Xiaoben

Year launched: 2025

With its round, chubby face, squirrel cheeks, playful smile, and soft, comforting appearance, Pouka Pouka aims to evoke feelings of warmth, healing, and emotional comfort.

Other characters to watch: CiciLu, Panda Roll (胖哒幼), NANCI (囡茜), FARMER BOB (农夫鲍勃), Rayan, Ozai (哦崽), Lulu the Piggy (LuLu猪), Pucky (毕奇).

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Chapter Dive

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

From ugly-cute rebellion to a new kind of ‘C-pop,’ the breakout success of Wakuku sheds light on Chinese consumer culture and the forces driving China’s trend toy industry.

Published

8 months agoon

July 6, 2025

Wakuku is the most talked-about newcomer in China’s trend toy market. Besides its mischievous grin, what’s perhaps most noteworthy is how closely Wakuku follows the marketing success of Labubu. As the strongest new designer toy of 2025, Wakuku says a lot about China’s current creative economy — from youth-led consumer trends to hybrid business models.

As it is becoming increasingly clear that Chinese designer toy Labubu has basically conquered the world, it’s already time for the next made-in-China collectible toy to start trending on Chinese social media.

Now, the name that’s trending is Wakuku, a Chinese trend toy created by the Shenzhen-based company Letsvan.

In March 2025, a new panda-inspired Wakuku debuted at Miniso Land in Beijing, immediately breaking records and boosting overall store revenue by over 90%. Wakuku also broke daily sales records on May 17 with the launch of its “Fox-and-Bunny” collab at Miniso flagship stores in Shanghai and Nanjing. At the opening of the Miniso Space in Nanjing on June 18, another Wakuku figure sold out within just two hours. Over the past week, Wakuku went trending on Chinese social media multiple times.

From left to right: the March, May, and June successful Wakuku series/figurines

Like Labubu, Wakuku is a collectible keychain doll with a soft vinyl face and a plush body. These designer toys are especially popular among Chinese Gen Z female consumers, who use them as fashion accessories (hanging them from bags) or as desk companions.

We previously wrote in depth about the birth of Labubu, its launch by the Chinese POP MART (founded 2010), and the recipe for its global popularity in this article, so if you’re new to this trend of Chinese designer toys, you’ll want to check it out first (link).

Labubu has been making international headlines for months now, with the hype reaching a new peak when a human-sized Labubu sold for a record 1.08 million RMB (US$150,700), followed by a special edition that was purchased for nearly 760,000 RMB (US$106,000).

Now, Wakuku is the new kid on the block, and while it took Labubu nine years to win over young Chinese consumers, it barely took Wakuku a year — the character was created in 2022–2023, made its retail debut in 2024, and went viral within months.

Its pricing is affordable (59–159 RMB, around $8.2-$22) and some netizens argue it’s more quality for money.

While Labubu is a Nordic forest elf, Wakuku is a tribal jungle warrior. It comes in various designs and colors depending on the series and is sold in blind boxes (盲盒), meaning buyers don’t know exactly which design they’re getting — which adds an element of surprise.

➡️ There’s a lot to say about Wakuku, but perhaps the most noteworthy aspect is how closely it mirrors the trajectory of POP MART’s Labubu.

Wakuku’s recent success in China highlights the growing appeal and rapid rise of Chinese IPs (beyond its legal “intellectual property” meaning, ‘IPs’ is used to refer to unique cultural brands, characters, or stories that can be developed into collectibles, merchandise, and broader pop culture phenomena).

Although many critics predict that the Labubu trend will blow over soon, the popularity of Wakuku and other Labubu-like newcomers shows that these toys are not just a fleeting craze, but a cultural phenomenon that reflects the mindset of young Chinese consumers, China’s cross-industry business dynamics, and the global rise of a new kind of ‘C-pop.’

Wakuku: A Cheeky Jungle Copycat

When I say that Wakuku follows POP MART’s path almost exactly, I’m not exaggerating. Wakuku may be portrayed as a wild jungle child, but it’s definitely also a copycat.

It uses the same materials as Labubu (soft vinyl + plush), the name follows the same ABB format (Labubu, Wakuku, and the panda-themed Wakuku Pangdada), and the character story is built on a similar fantasy universe.

In fact, Letsvan’s very existence is tied to POP MART’s rise — the company was only founded in 2020, the same year POP MART, then already a decade old, went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and became a dominant industry force.

In terms of marketing, Wakuku imitates POP MART’s strategy: blind boxes, well-timed viral drops, limited-edition tactics, and immersive retail environments.

It even follows a similar international expansion model as POP MART, turning Thailand into its first stop (出海首站) — not just because of its cultural proximity and flourishing Gen Z social media market, but also because Thailand was one of the first and most successful foreign markets for Labubu.

Its success is also deeply linked to celebrity endorsement. Just as Labubu gained global traction with icons like BLACKPINK’s Lisa and Rihanna seen holding the doll, Wakuku too leans heavily on celebrity visibility and entertainment culture.

Like Labubu, Wakuku even launched its own Wakuku theme song.

Since 2024, Letsvan has partnered with Yuehua Entertainment (乐华娱乐) — one of China’s leading talent agencies — to tap into its entertainment resources and celebrity network, powering the Wakuku marketing engine. Since stars like Esther Yu (虞书欣) were spotted wearing Wakuku as a jeans hanger, demand for the doll skyrocketed. Yuehua’s founder, Du Hua (杜华), even gifted a Wakuku to David Beckham as part of its celebrity strategy.

From Beckham to Esther Yu; celebrity endorsements play a big role in the viral marketing of Wakuku.

But what’s most important in Wakuku’s success — and how it builds on Labubu — is that it fully embraces the ugly-cute (丑萌 chǒu méng) aesthetic. Wakuku has a mischievous smile, expressive eyes, a slightly crooked face, a unibrow, and freckles — fitting perfectly with what many young Chinese consumers love: expressive, anti-perfectionist characters (反精致).

“Ugly-Cute” as an Aesthetic Rebellion

Letsvan is clearly riding the wave of “ugly trend toys” (丑萌潮玩) that POP MART spent years cultivating.

🔍 Why are Chinese youth so obsessed with things that look quirky or ugly?

A recent article by the Beijing Science Center (北京科学中心) highlights how “ugly-cute” toys like Labubu and Wakuku deviate from traditional Chinese aesthetics, and reflect a deeper generational pushback against perfection and societal expectations.

The pressure young people face — in education, at work, from family expectations, and information overload — is a red thread running through how China’s Gen Z behaves as a social media user and consumer (also see the last newsletter on nostalgia core).

To cope with daily stress, many turn to softer forms of resistance, such as the “lying flat” movement or the sluggish “rat lifestyle” in which people reject societal pressures to succeed, choosing instead to do the bare minimum and live simply.

This generational pushback also extends to traditional norms around marriage, gender roles, and ideals of beauty. Designer toys like Labubu and Wakuku are quirky, asymmetrical, gender-fluid, rebellious, and reflect a broader cultural shift: a playful rejection of conformity and a celebration of personal expression, authenticity, and self-acceptance.

Another popular designer toy is Crybaby, designed by Thai designer Molly, and described as follows: “Crybaby is not a boy or a girl, it is not even just human, it represents an emotion that comes from deep within. It can be anything and everything! Laughter isn’t the only way to make you feel better, crying can be healing too. If one day, a smile can’t alleviate your problems, baby, let’s cry together.”

But this isn’t just about rejecting tradition. It’s also about seeking happiness, comfort, and surprise: emotional value. And it’s usually not brand-focused but influencer-led. What matters is the story around it and who recommends it (unless the brand becomes the influencer itself — which is what’s ultimately happening with POP MART).

One of the unofficial ambassadors of the chǒu méng ugly-cute trend is Quan Hongchan (全红婵), the teenage diving champion and Olympic gold medallist from Guangdong. Quan is beloved not just for her talent, but also for her playful, down-to-earth personality.

During the Paris Olympics, she went viral for her backpack, which was overflowing with stuffed animals (some joked she was “carrying a zoo on her back”) — and for her animal-themed slippers, including a pair of ugly fish ones.

Quan Hongchan with her Wakuku, and her backpack and slippers during her Paris Olympics days.

It’s no surprise that Quan Hongchan is now also among the celebrities boosting the popularity of the quirky Wakuku.

From Factory to Fandom: A New Kind of “C-pop” in the Making

The success of Wakuku and other similar toys shows that they’re much more than Labubu 2.0; they’re all part of a broader trend tapping into the tastes and values of Chinese youth — which also speaks to a global audience.

And this trend is serious business. POP MART is one of the world’s fastest-growing consumer brands, with a current market value of approximately $43 billion, according to Morgan Stanley.

No wonder everyone wants a piece of the ‘Labubu pie,’ from small vendors to major companies.

It’s not just the resellers of authentic Labubu dolls who are profiting from the trend — so are the sellers of ‘Lafufu,’ a nickname for counterfeit Labubu dolls, that have become ubiquitous on e-commerce platforms and in toy markets (quite literally).

Wakuku’s rapid rise is also a story of calculated imitation. In this case, copying isn’t seen as a flaw but as smart market participation.

The founding team behind Letsvan already had a decade of experience in product design before setting out on their journey to become a major player in China’s popular designer toy and character merchandise market.

But their real breakthrough came in early 2025, when QuantaSing (量子之歌), a leading adult learning ed-tech company with no previous ties to toys, acquired a 61% stake in the company.

With QuantaSing’s financial backing, Yuehua Entertainment’s marketing power, and Miniso’s distribution reach, Wakuku took it to the next level.

The speed and precision with which Letsvan, QuantaSing, and Wakuku moved to monetize a subcultural trend — even before it fully peaked — shows just how advanced China’s trend toy industry has become.

This is no longer just about cute (or ugly-cute) designs; it’s about strategic ecosystems by ‘IP factories,’ from concept and design to manufacturing and distribution, blind-box scarcity tactics, immersive store experiences, and influencer-led viral campaigns — all part of a roadmap that POP MART refined and is now adopted by many others finding their way into this lucrative market. Their success is powered by the strength of China’s industrial & digital infrastructure, along with cross-industry collaboration.

The rise of Chinese designer toy companies reminds of the playbook of K-pop entertainment companies — with tight control over IP creation, strong visual branding, carefully engineered virality, and a deep understanding of fandom culture. (For more on this, see my earlier explanation of the K-pop success formula.)

If K-pop’s global impact is any indication, China’s designer toy IPs are only beginning to show their potential. The ecosystems forming around these products — from factory to fandom — signal that Labubu and Wakuku are just the first wave of a much larger movement.

– By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Spring Festival Trend Watch: Gala Highlights, Small-City Travel, and the Mazu Ritual Controversy

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive8 months ago

Chapter Dive8 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West