China Memes & Viral

The Benz Guy from Baoding and the Granny Xu Line-Cutting Controversy

While the public initially supported ‘Grandma Xu’ and criticized the Benz driver from Baoding, the narrative took an unexpected turn.

Published

2 years agoon

Following the rapid spread of a video capturing a man and woman involved in a road rage incident, Chinese netizens named and shamed them. But when the situation turned out to be different than it seemed, the focus of the story shifted, emphasizing the responsibility of the so-called ‘melon-eating masses’ actively participating in these kind of hyped-up incidents.

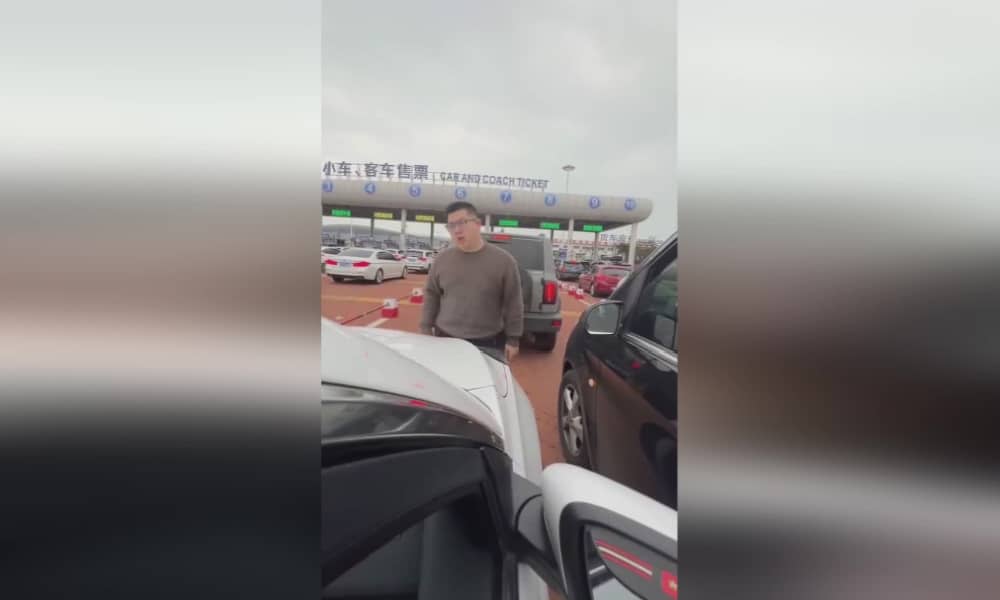

A Baoding license plate with the number 冀F8656Z briefly became China’s most talked-about car tag this week following a road rage incident that was captured on camera (see video). The incident involved the passenger of a black Mercedez-Benz, who went viral on Chinese social media for smashing the hood of another car at a ferry terminal in Zhanjiang. The altercation was triggered by a dispute over line-cutting.

The incident occurred on the afternoon of January 29 at Zhanjiang’s Xuwen Port, where vehicles were queuing up in the car and coach ticket lane. When a Mercedes-Benz Vito attempted to cut into the line, a white Chery car – with an older woman in the passenger seat – refused to yield. In response, the alleged Mercedes owner (male) and another passenger (female) angrily exited their vehicle and scolded the white car’s driver and passenger, as well as slamming their hood and seemingly causing damage to the car.

Meanwhile, the black Mercedes, apparently driven by a third individual, proceeded to cut in line and eventually drove off after the passengers got back in.

The 71-year-old lady in the white car who recorded the incident, Ms Xu or Granny Xu (徐老太), just so happened to have a relatively large social media following on a Douyin account run by her daughter (五莲徐八月). When she posted the video of the incident online, her 500,000 followers (now 800,000) came into action to name and shame the couple who insulted and intimidated her. As a result, the license plate, clearly visible in the footage, became a top trending search query.

This phenomenon, wherein netizens unite to research and expose information about individuals involved in controversial incidents, is also known as the “Human Flesh Search Engine” (人肉搜索) in Chinese (read more).

On January 30, the story started gaining massive attention on Chinese social media and online media sites. What mostly angered people was not just the arrogant and aggressive behavior of the Benz passengers, but also the fact that they acted so rude and entitled toward an elderly lady.

It came out that the aggressive man, the 40-year-old Mr. Wang, is a teacher at Hebei Agricultural University, and people started targeting their anger towards the Agricultural University, the city of Baoding, and even Hebei province as a whole.

The couple triggered China’s meme machine and popped up in various funny edited images.

“Do not cut in line” bumper stickers showing the Benz guy from Baoding.

They even appeared on some online merchandise, namely on bumper stickers warning others not to cut in line.

Another Point of View

While the public initially supported ‘Grandma Xu’ and criticized the Benz driver from Baoding, the narrative took an unexpected turn. Because in the midst of this controversy, dashcam footage from the Mercedes Benz also surfaced online, along with other images showing the scene from different angles.

This footage offered an alternative perspective, revealing that the Benz driver was attempting a zipper-style merge into the lane but was intentionally blocked by the white car, with the passenger filming the confrontation.

Later on, the surveillance video from the Xuwen Port was also released (video). That 7-minute video showed the entire conflict from the start, and although it showed that the Mercedes driver was at fault for cutting in line and damaging Xu’s car, it also showed that the Chery car was not without fault.

The new information caused a shift in public opinion as people started to think the Ms Xu purposely misrepresented the situation by omitting her role in the traffic altercation. It also became evident that, contrary to initial assumptions, Ms. Xu was not the driver of the white sedan at all; instead, a younger male was behind the wheel.

Bird’s eye view images of Xuwen Port also revealed that in lane 7, where the altercation occurred, all cars eventually merge in a zipper-style pattern.

As a result, both the Benz driver and the elderly lady now faced public condemnation – one for traffic misconduct, the other for distorting the truth on social media.

The Role of the Melon Eaters

As online discussions about the entire incident are still unfolding, there’s been a change in what people focus on regarding this story.

Initially, the rude and agressive Benz guy and his female companion, a meme-worthy couple, were the main topic of conversation. Then, as people started realizing the role played by the so-called ‘granny’ influencer – who edited and posted the footage in such a way that made her seem like the mere victim, – they were angry at her.

Ultimately, however, some commentators and bloggers noted that it is actually the so-called ‘melon eating masses’ who are responsible for making this story go viral and choosing sides without knowing all the facts. The Chinese term is chīguā qúnzhòng (吃瓜群众), translated as melon-eating masses or peanut gallery, referring to the netizens who are enjoying the spectacle as it unfolds, sharing details or opinions with limited knowledge.

While the story is still simmering online, the the Xuwen County Public Security Bureau has imposed a 10-day administrative detention and a fine of 500 yuan ($70) on Mr Wang for his actions of smashing the hood of the car. Ms Xu reportedly is getting her car fixed, renewing the entire hood of the dented sedan.

The original video that sparked all the controversy has since been removed from Ms Xu’s Douyin account.

In the end, the story has a negative impact on both Wang and Xu, which will probably haunt them for some time to come. The only one benefiting is the seller of ‘please don’t cut in line’ bumper stickers, which have since become a viral success.

Regardless of all disagreements regarding this incident, there’s one thing virtually everyone agrees with, especially during this busy Chinese New Year travel season: bad traffic etiquette and cutting in line is not cool, and resorting to aggression and vandalism is never the solution.

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Arts & Entertainment

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

With China’s box office relay tradition, every movie’s success becomes a win for Chinese cinema.

Published

3 days agoon

August 20, 2025

When one film breaks a record in China, the previous champion often celebrates with a playful and creative congratulatory poster. It’s a uniquely Chinese mix of solidarity, box-office success, and internet culture.

China’s 2025 summer box office season has been a success, surpassing 10 billion yuan (~US$1.4 billion), driven by record-breaking domestic films that have also made waves on Chinese social media.

Somewhat unexpectedly, the Chinese 2D animated feature Nobody (浪浪山小妖怪) has emerged as the season’s breakout hit.

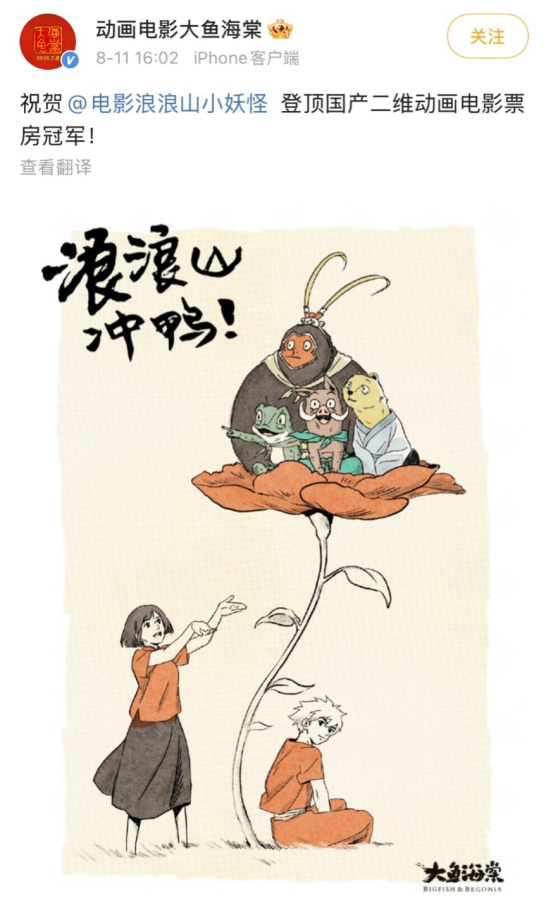

On August 11, Nobody overtook the total earnings of the 2016 hit Big Fish & Begonia (大鱼海棠), also a domestically produced animation, becoming the highest-grossing domestic 2D animated film in Chinese history.

In keeping with industry tradition, Big Fish & Begonia celebrated the milestone by releasing a congratulatory poster on its official Weibo account.

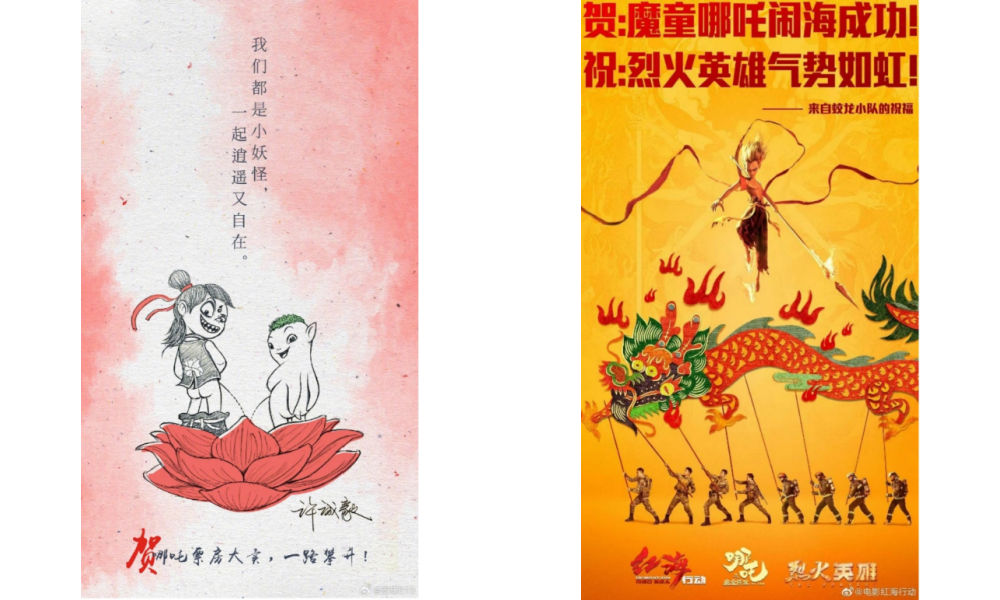

The poster shows the quirky characters of Nobody sitting on top of a giant red flower, while the protagonists of Big Fish & Begonia cheer them on from below. Written in bold calligraphy (“浪浪山冲鸭!”) is a playful phrase to cheer the movie on (translatable as: “Go, Langlang Mountain!” [Langlang Mountain is the original Chinese title.])

This is a unique “tradition” in China’s film industry: whenever a movie breaks a box-office record—no matter the category—the previous record-holder pays tribute by releasing a specially designed “congratulatory poster” in a gesture of camaraderie.

These posters are usually shared through the official Weibo accounts of the former champions, as it is common for Chinese film and TV drama productions to have their own accounts on Weibo.

Origins of the Poster Relay in China

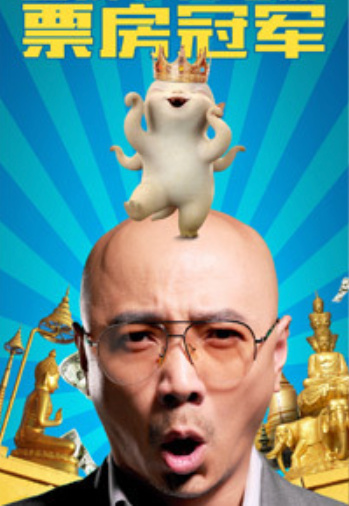

The tradition of the so-called “box-office champion poster relay” (票房冠军海报接力) in China dates back to 2015, when Xu Zheng’s hit Lost in Thailand (泰囧)—which had held the record for highest-grossing domestic film since 2012 with a box office of 1.267 billion yuan (~US$200M)—was overtaken by Monster Hunt (捉妖记), which went on to gross 2.44 billion yuan (~US$340M).

Director Xu Zheng, who also starred in Lost in Thailand, took the initiative to release a humorous congratulatory poster for Monster Hunt. In the image, the little monster Huba (胡巴) is shown dancing on Xu’s bald head, accompanied by the text: “Lost in Thailand congratulates Monster Hunt on topping the Chinese box office.”

The poster that started a tradition.

Then, in 2016, Stephen Chow’s The Mermaid (美人鱼) surpassed Monster Hunt with a box office take of over 2.44 billion yuan (~US$340M). In response, the Monster Hunt team also released a congratulatory poster showing its main character Huba transformed into a mermaid, gazing up at the tail of The Mermaid.

The text on the poster reads: “Xing Ye (星爷) reaches the top, and Huba comes to congratulate him” — Xing Ye being Stephen Chow’s well-known nickname in Chinese. The vertical text on the right quoted lyrics from The Mermaid’s theme song: “You ask if this mountain is the highest in the world — there are always mountains higher than the other.”

Monster Hunt had been congratulated for its own win; now it was its turn to congratulate The Mermaid.

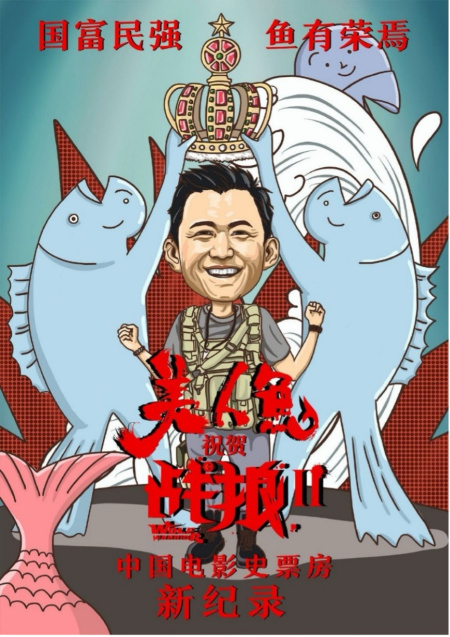

The relay continued in 2017 when Wolf Warrior 2 (战狼2) became the first Chinese film to cross the 5-billion-yuan mark (~US$700M), topping the chart. The Mermaid sent its congratulations with a poster featuring the Mermaid placing a crown on Wu Jing (吴京), the director and star of Wolf Warrior 2.

Caption: The Mermaid’s congratulatory poster for Wolf Warrior 2 in 2017. The text at the top reads: “When the nation is prosperous and the people are strong, the Mermaid shares in the honor.”

Beyond the Championship

Over time, the tradition expanded. Films that were overtaken in the rankings, even if it was not a change of the championship, also began releasing congratulatory posters.

In 2019, the animated sensation Ne Zha 1 (哪吒之魔童降世) surpassed a string of blockbusters, including Monster Hunt, Operation Red Sea (红海行动), and The Wandering Earth (流浪地球), to become the second-highest-grossing Chinese film at the time. Each of these films then sent their own tribute to “Little Nezha.”

A hand-drawn congratulatory poster by Xu Chengyi (许诚毅), the director of Monster Hunt, said: “We are all little monsters, free and easy together,” as a slight twist on Nezha’s classic line from the movie.

Congratulatory posters by Monster Hunt and Operation Red Sea to celebrate the success of Ne Zha in 2019.

The congratulatory poster by Operation Red Sea to Ne Zha 1 in 2019 also included a reference to The Bravest (烈火英雄), another film from the same producer, Bona Film Group, released at the same time as Ne Zha 1. In doing so, Bona used the popularity of Ne Zha 1 to promote its own new film at the same time.

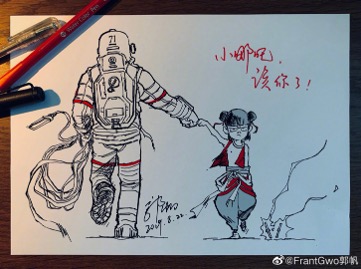

Congratulatory poster by Guo Fan(郭帆), director of The Wandering Earth.

In 2019, Guo Fan (郭帆), the director of The Wandering Earth (流浪地球), hand-drew a congratulatory poster for Ne Zha. The illustration featured playful artwork accompanied by the text: “Little Nezha, now it’s your turn!”

Ne Zha also set a milestone for Chinese animation in an international context, earning 1.834 billion yuan (~US$260M) within nine days and reclaiming the animated film box office record in China from Zootopia.

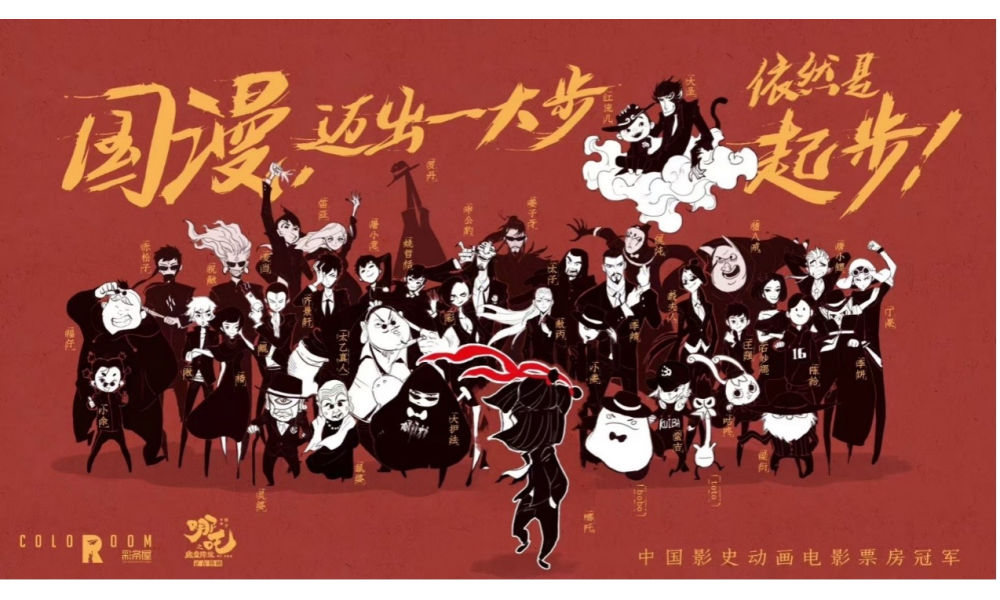

Coloroom Pictures, the producer of Ne Zha and other Chinese animated hits, marked the achievement with a poster that both celebrated the unity of China’s animation community and acknowledged the challenges that still lay ahead, writing: “Chinese animation has taken a big step forward, but it is still just starting out.”

The poster features dozens of Chinese anime characters in formal dress, with Little Nezha standing in front of them and looking back.

These kinds of online congratulatory wishes, resonating with netizens, continued in 2021 when Hi, Mom (你好,李焕英) climbed to second place in China’s all-time box office.

Ne Zha 1 then released a hand-drawn poster showing Nezha sitting on the back of his mother’s bicycle, vowing to make something of himself—a promise fulfilled four years later when Ne Zha 2 actually surpassed Hi, Mom in early 2025.

Ne Zha 1’s congratulatory poster to Hi, Mom in 2021. The poster depicted a scene in front of Chentangguan Cinema where Hi, Mom is being shown, with Nezha sitting on the back seat of his mother’s bicycle (a classic scene in Hi, Mom’s promotion poster), vowing, “Mom, I will surely make something of myself when I grow up.”

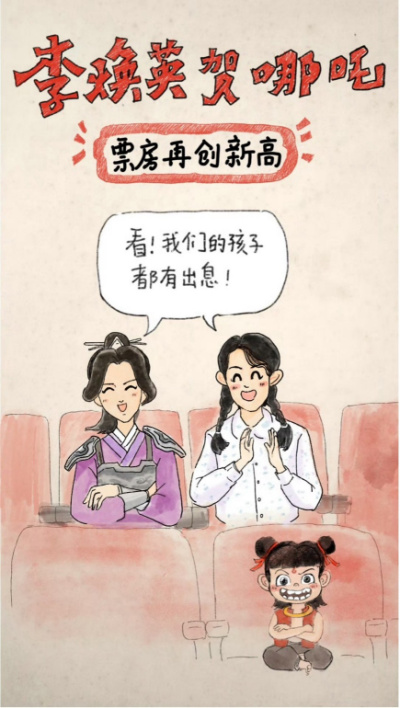

In return, Hi, Mom published a poster in a matching style to response Ne Zha’s congratulatory poster in 2021.

Hi, Mom’s congratulatory poster to Ne Zha 2 in 2025, in which Nezha’s mother and the mother from Hi, Mom sitting together and applauding for the success of Ne Zha 2, saying, “Look! Our children are all promising.”]

All these exchanges have created unexpected interactions between vastly different movie genres.

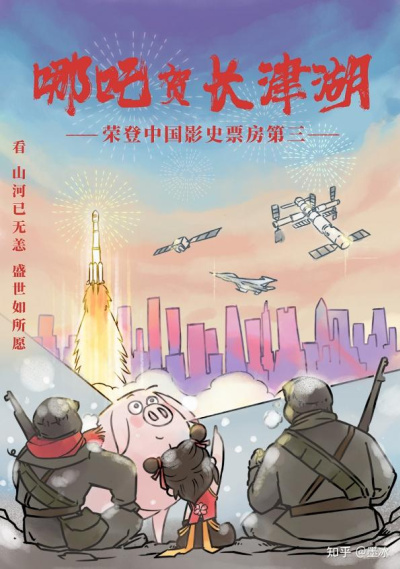

In November 2021, when the war epic The Battle at Lake Changjin (长津湖) surpassed Chinese animation feature Ne Zha 1, the congratulatory poster released by Ne Zha 1 depicted Nezha alongside volunteer army soldiers, gazing at rockets, fighter jets, and satellites.

Ne Zha 1’s congratulatory poster to The Battle at Lake Changjin in 2021.

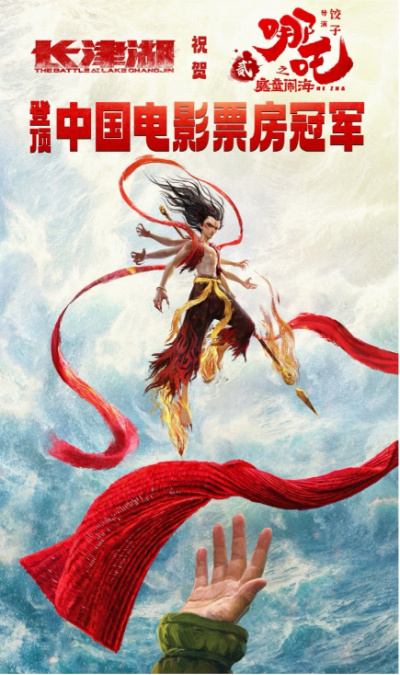

In 2025, when Ne Zha 2 seized the all-time box-office crown, The Battle at Lake Changjin also responded with a creative image.

The Battle at Lake Changjin’s congratulatory poster to Ne Zha 2 in 2025.

In that image, Nezha’s magical weapon the Hun Tian Ling (混天绫) was ingeniously linked to the red scarf thrown to soldiers in The Battle at Lake Changjin. At the bottom, a soldier’s large hand is shown in a lifting gesture, holding Nezha up.

The concept of such a serious war movie interacting with a humorous animated film sparked some excitement among Chinese netizens at the time. They saw the exchange as a dialogue between traditional mythology and modern history, and as a symbol of the continuity and success of China’s film industry.

A Unique Chinese Tradition?

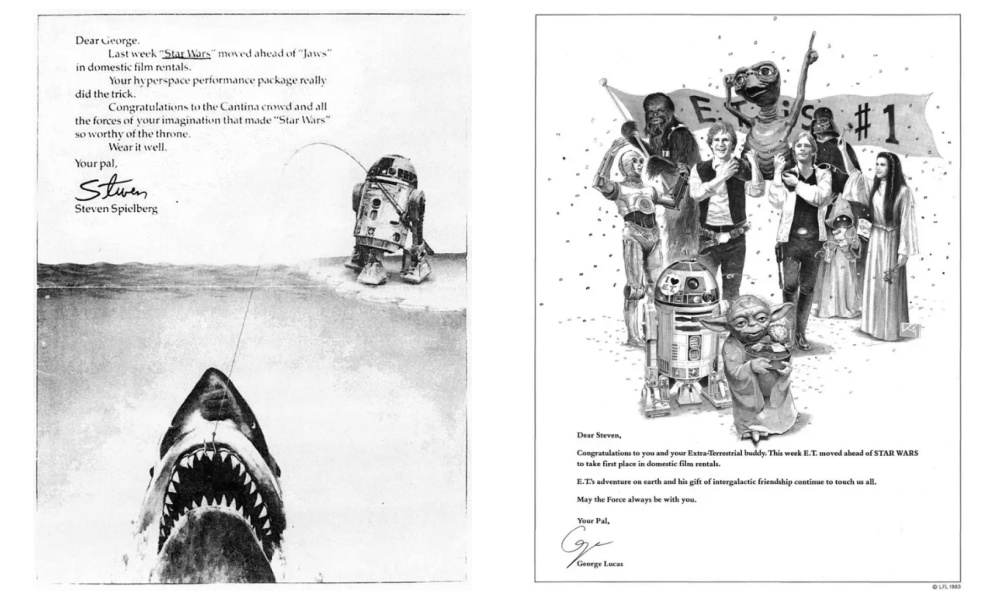

The custom of one film “passing on the torch” to the next hit film through a congratulatory message is not entirely unique to China. The practice can actually be traced back to Hollywood.

In 1977, when Star Wars dethroned Jaws at the North American box office, director Steven Spielberg congratulated George Lucas with a full-page ad in Variety, humorously depicting R2-D2 reeling in the great white shark.

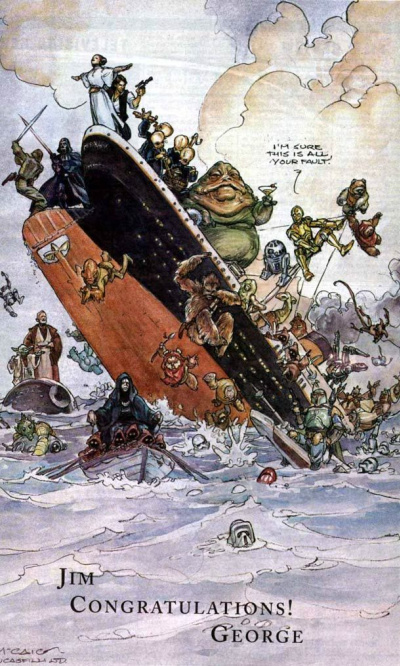

When Star Wars was dethroned by Titanic at the global box office in 1998, George Lucas sent a famous congratulatory message to James Cameron, again as a full-page ad in Variety.

Star Wars meets Titanic, famous congratulatory message to James Cameron .

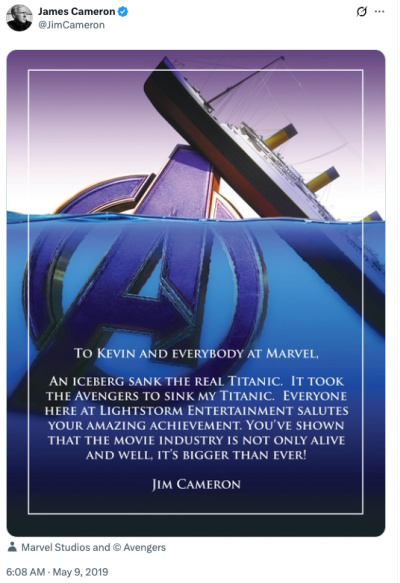

In May 2019, when Avengers: Endgame officially overtook Titanic’s worldwide box office total to become the second-highest-grossing film of all time (behind Avatar), James Cameron — director of both Titanic (1997) and Avatar (2009) — posted a congratulatory image to salute Marvel Studios.

James Cameron on Twitter in May 2019.

So, although the practice of “passing the torch” among box office record-holders is not uniquely Chinese, the way it has developed in China is very distinct:

🔹 In Hollywood, box-office champions often hold the crown for years, and the ‘changing of the guards’ is relatively rare. In China, however, the industry has flourished mainly in the past decade, and records are broken far more frequently.

🔹 Social media has become central to promotion and marketing. Virtually all major Chinese films run active official accounts that not only post promotional material but also engage in playful interactions with other productions.

🔹 In Hollywood, congratulatory notes tend to come from individual directors, who salute each other as “friendly competitors.” In China, the messages are sent from the films’ official accounts, presenting it more as team-to-team recognition.

🔹 In that sense, it’s not just “movie versus movie,” but rather the Chinese film industry collectively measuring itself against Hollywood and other foreign hits. Each congratulatory poster is therefore not only a celebration of a new record, but also a statement of pride in the broader success of Chinese cinema.

🔹 Participation is not limited to the very top box-office leaders; other productions often join in, creating a ripple effect of collective celebration.

In China, the frequent turnover of box-office leaders combined with the creativity of these posters has turned the practice into a beloved feature of both film culture and the social media landscape.

In an earlier online poll, a majority of respondents described the tradition as “encouraging, and a demonstration of solidarity in China’s film industry.” Others called it a form of “romantic etiquette” unique to Chinese cinema.

Most importantly, it simply feels good — a win-win for both older and newer productions. As one netizen wrote after seeing the congratulatory artwork from Big Fish & Begonia’s official account: “I was inspired and hope that these little monsters can give everyone the courage to set out on their journeys, as well as the strength and passion to pursue their dreams. I hope domestic animation will keep getting better and better!”

By Wendy Huang

Edited by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at

info@whatsonweibo.com

China Memes & Viral

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

Behind the hashtag about Nanjing’s cross-dressing ‘Sister Hong’: from legal implications to viral spectacle.

Published

1 month agoon

July 17, 2025

A 60-year-old man from Nanjing became the biggest trending topic on Weibo recently after news circulated that he had cross-dressed as a woman, lured 1,691 men into having sex with him, recorded the encounters, and then spread the videos online. It was suggested that he had exposed the men to HIV and infected at least eleven of them.

That particular story turned out to be inaccurate, but the real story behind the sensationalism was strange enough to pique the interest of countless netizens.

The actual case involves a much younger man: the 38-year-old Mr. Jiao who pretended to be a woman and arranged to hook up with many men, secretly recording the encounters and uploading the footage online.

Mr Jiao and screenshots of some of their videos.

The story first began circulating online in early July. It went viral across multiple Chinese social media platforms after local police arrested the man and publicly announced the case (likely also due to the rapid spread of sensationalized rumors).

This is what the police report of July 8 said:

Police notification

Recently, Jiangning police received reports from members of the public stating that their private videos had been disseminated online by others. Jiangning police immediately launched an investigation and, on July 5, arrested the suspect Jiao (焦) X.

Upon investigation, it was found that Jiao X. (male, 38 years old, person from outside the province) impersonated a woman, arranged to engage in sexual activities with multiple men, and secretly filmed the encounters to disseminate the videos online.

The widely spread online rumor that “a 60-year-old man in Nanjing dressed as a woman and had intimate relations with over a thousand people” is false.

On July 6, Jiao X. was criminally detained by Jiangning police in accordance with the law on suspicion of the crime of disseminating obscene materials. The case is currently under further investigation.

Jiangning Branch of the Nanjing Public Security Bureau

July 8, 2025

By now, the case has come to be known as the “Nanjing Old Guy Hong Incident” (南京红老头事件). In Chinese, “Hong” (红) means “red,” which is not only a color but also carries connotations of celebrity or notoriety in this context.

Jiao initially used the online nickname Ah Hong (阿红). This nickname soon evolved into “Nanjing Sister Hong” (南京红姐), but was later changed by netizens to “Nanjing Old Guy Hong” (南京红老头) after some argued it was inappropriate to refer to Jiao as a woman. Official media posts calling Jiao “Sister” received hundreds of angry reactions, with people demanding an end to the use of the female title.

Jiao had reportedly posed as a woman for a long time, using various social platforms—from WeChat and QQ to Momo—to find men to hook up with.

He wore women’s clothing, a long wig, used heavy white make-up, and also relied on beauty filters and voice-changing tools to appear and sound more feminine to the men he met online.

Since Jiao didn’t charge any money for these encounters, some of the men apparently thought it polite to bring gifts. Leaked footage shows visitors arriving at his apartment with small offerings—from fruit and milk to half-full bottles of cooking oil (how romantic).

Caption: “I’m dying of laughter — someone even brought half a jug of cooking oil from home. There were people bringing milk, fruits, even a pack of tissues — but the funniest thing is someone actually brought half a jug of cooking oil from their own kitchen! Hahaha. Tomorrow morning, when his wife cooks, she’s definitely going to wonder where the oil went.”

Jiao had secretly set up a hidden camera in the rooms to capture the sexual encounters, and later spread these online through online groups where participants had to pay a membership fee of 150 yuan (US$21) per person to join the group.

Some of Jiao’s victims reported him to the police after discovering that videos of their encounters were being circulated online—allegedly after they were recognized by others. By now, several men have been identified by people who know them, and one woman reportedly recognized her own husband in one of the videos.

The exact number of men Jiao met and filmed remains unknown. While authorities have dismissed the viral claim of over 1,600 men as exaggerated — a number reportedly mentioned by Jiao himself — they have not released an official count, and the investigation is still ongoing.

The videos have since spread widely online, showing Jiao engaging in various forms of sexual activity with different male partners, including oral and anal intercourse. While it’s unclear how many of the men initially believed he was a woman, it seems highly likely—if not inevitable—that many realized the truth at some point during the encounters.

Social media discussions around the case now touch on a range of issues, from privacy violations to gender identity and public health concerns.

🏛️ Legal Implications: From Violating Privacy to Endangering Public Health

First, the legal aspects of the case are drawing significant attention, with various lawyers and legal experts weighing in on what crimes Jiao may have committed. For now, he is under criminal detention for disseminating obscene materials—the production, distribution, and sale of sexually explicit content is illegal under Chinese law.

But Jiao also violated the privacy and portrait rights of others by sharing explicit videos that clearly show their faces without consent.

And what if Jiao is indeed HIV-positive and knowingly engaged in unprotected sex? According to Legal Daily (法治日报), he could then be charged with “endangering public safety through dangerous means” (“以危险方法危害公共安全罪”).

This offense carries a sentence of 3 to 10 years in prison if no serious harm occurs, but if it results in severe injury, death, or major damage, it could lead to life imprisonment or even the death penalty.

On the morning of July 8, a local CDC official confirmed that health authorities were now involved in the case. While Jiao’s health status is considered private, officials said they’ll share updates if and when it’s appropriate.

💥 Social Shock: Public Health and “Hole-Sexuals”

There has also been significant social shock over the story. The footage that’s been circulating online shows dozens of different men visiting Jiao — from student types and businessmen to men from all walks of life, including fitness trainers, married men, college athletes, and also young foreign men.

Many netizens expressed that the story changed the way they view the people around them. The men visiting Jiao were not some ‘basket of deplorables’ — they included wealthy older men, young and attractive guys, educated tech professionals. That realization unsettled many, shaking their worldview on multiple levels.

Although this triggered many jokes, it also raised uncomfortable questions not just about how little people may know their friends, neighbors, or even romantic partners—but also about public health. If Jiao did pose an HIV risk, it means these men—many of whom are married or have families—may have unknowingly brought that risk home with them after these unprotected encounters arranged online.

Chinese commentators and bloggers therefore tied the case to women’s sexual health, suggesting that a significant number of gynecological infections among married women are actually caused by their own husbands.

There were multiple online posts suggesting that the entire story reflected the sexual repression experienced by many Chinese men. Jiao, as a man himself, may have understood male psychology well — and was simply giving these men the emotional and physical attention they were lacking at a time when their sexual needs were not being met.

Some argued that such situations are a byproduct of the crackdown on KTV bars and massage parlors, hinting at the shrinking space for illegal prostitution in mainland China.

“Sometimes it really feels like heterosexuality is a joke,” blogger Chen Shishi (@陈折折) wrote: “These men are so filthy, and yet they go back and pretend to be good boyfriends, good husbands, good fathers, good men.”

She added: “As long as there’s a hole, they’re in.”

In doing so, Chen used the term 洞性恋 (dòngxìngliàn), a satirical play on the Chinese word for “homosexual” (同性恋, tóngxìngliàn, literally “same-sex love”).

By replacing the first character 同 (“same”) with 洞 (meaning “hole”), the term becomes “hole-sexual” instead of “homosexual,” mocking those men who sought out Jiao without caring what “she” looked like — or even whether she was secretly a man — as long as there was a “hole” to satisfy them. Recently, 洞性恋 (dòngxìngliàn) has been used a lot by Chinese netizens commenting on this case.

🛑 Politically Sensitive: Controlling the Narrative

Apart from the criminal charges Jiao may face, this story inevitably has some deeper layers that are politically sensitive and are therefore flattened and rewritten into safer territories.

Chinese well-known blogger Lu Shihan (@卢诗翰) recently commented on this issue on Weibo and Zhihu, critiquing how Chinese media and public discourse have framed this story. According to Lu, the narrative was intentionally shifted away from any discussion of a possibly trans, marginalized sex worker.

Lu suggests that censorship, social discomfort, and political sensitivity around class struggles and LGBTQ+ issues force both media and the public to stick to the safest possible framing.

That “safe narrative” is a comical and odd case about a ridiculous old man in a wig, crossdressing for his own fetish pleasure and spreading obscenity, scamming straight men into a sex scandal.

Acknowledging that many of the men may have known (or didn’t care) that “Nanjing Sister Hong” was biologically male would turn the incident into a conversation about queer identity and sexuality. And as Lu points out, that’s a no-go zone.

In his commentary on the issue, Lu Shihan mentions the story of another “Sister Hong” (红姐), an older street sex worker who became well-known in Shenzhen’s Sanhe district and even gained some online fame at a national level.

“Sanhe Sister Hong” came from a mountainous village and ran away as a teenager to work in the city. After being abused and abandoned, she fell into homelessness and eventually turned to sex work to survive in Sanhe, a place known for its lower-class young (post-1990) male day laborers who hop from job to job, self-precariously calling themselves the “great gods of Sanhe” (三和大神). In this environment, Sister Hong stood out not just as a sex worker but also as a vagabond woman, and she has almost reached cult-like status for some—she’s now known the legendary Sister Hong.

Sanhe Sister Hong.

“Nanjing Sister Hong” ultimately got that nickname because of the “Sanhe Sister Hong.”

Lu argues that around China, from Nanjing to Shenzhen to Guangdong, there are many “Sister Hongs,” and their vulnerable position, marginalization, and methods of income have to do with much deeper issues about gender and class struggles that go beyond some clueless straight men who just happen to stumble into their bedrooms.

On Chinese Q&A site Zhihu, some commenters are convinced that Jiao’s ‘customers’ were very well aware that he was not a woman — but that it is common to see men dressing up as women for a certain group of closeted men who feel more at ease in ambiguous, feminized encounters that don’t directly confront their own sexual identities. Also, for them, people like Sister Hong feel like safer territory.

🎭 Cultural Fascination: The Story of Shi Peipu

At the heart of this story also lies a deeper cultural fascination: the image of a male figure assuming a female persona to seduce other men — and the taboo topics that come with it. Cross-dressing has a long history in China, from traditional opera to contemporary media.

Some netizens — somewhat jokingly — compared “Sister Hong” (Jiao) to the case of Shi Peipu (时佩璞), a story that inspired the award-winning play M. Butterfly (1988) by David Hwang.

Shi Peipu (1938–2009) was a male Chinese opera singer who pretended to be a biological woman for over two decades. Shi Peipu worked for the Chinese secret service and was involved in what has been called one of the “strangest cases in international espionage.”

Shi Peipu

Shi Peipu was originally from Kunming and moved to Beijing in the 1960s. The then 26-year-old Shi met the French diplomat Bernard Bouriscot (布尔西, 1944) at a Christmas party in 1964, where Shi came dressed as a man.

Shi told Bouriscot that he was actually a female opera singer who had been forced by his father to present himself as a man because he desired a son so much. Bouriscot believed it, and their love affair took off — a romance that also continued when Bouriscot was stationed abroad.

For a period of twenty years, Shi pretended to be a woman during this ‘love relationship’ in order to gather intelligence information from Bouriscot.

Shi went to extreme measures to keep the Frenchman close to him, as ‘she’ even convinced Bouriscot that she had become pregnant with his child in 1965, just before the two would be apart for a long time. Shi adopted a boy from Xinjiang and presented him as their alleged child, which Bouriscot apparently believed.

Bouriscot and his son, who was actually adopted and not biologically his.

In 1982, Shi and Bouriscot moved to Paris, where they were both arrested a year later — Shi’s secret allegedly finally came to light when the CIA informed the French government that secret information from the French Embassy in China had leaked during the 1970s.

Even when the police burst into their home to arrest them, the Frenchman allegedly still believed Peipu was his wife and the mother of his child. It took a medical report for him to realize the truth.

Bouriscot attempted suicide when he discovered that Shi was actually a man. He was convicted of espionage — news that made it to the front pages in France — and both men were sentenced to six years in prison (although both got out earlier).

Front page of France Soir after Bouriscot and Shi Peipu were arrested on June 30, 1983, and later convicted.

Shi, who did not plead guilty to being a spy, passed away in Paris in 2009. About the affair, Bouriscot later said: “When I believed it, it was a beautiful story.”

Shi Peipu’s story has become one of those famous stories that is still discussed online and pops up every now and then — such as in the discussions talking about “Sister Hong.” Because the story is so bizarre, it is mostly discussed in certain frameworks that hardly challenge dominant ideas about gender and sexuality.

📌 So what’s the takeaway in the “Sister Hong” case? On the surface, it serves as a cautionary tale about meeting strangers online, and the potential nightmare of seeing yourself butt-naked on the internet.

But more deeply, the reason this case shook the Chinese internet is because it points to something much larger. It touches on issues that usually remain hidden beneath the surface. It reveals vulnerability on all sides.

The vulnerability of people like “Nanjing Sister Hong” — whether cross-dressing or identifying as transgender, they are operating outside the gender binary. As research by scholars like Eileen Yuk-ha Tsang shows, people in this position often face social stigma, family rejection, discrimination, severe depression, and abuse by their intimate partners (many of whom present as heterosexual men). While none of this excuses Jiao’s actions — secretly recording hundreds of men and exposing their faces and literal private parts online — it does shed light on some of the dynamics that may have pushed him into the darker corners of the internet.

There’s also the vulnerability of the men who were filmed — now watching their lives collapse as their identities are exposed to the public.

And then there’s the vulnerability of the wives and partners at home — not only discovering their partners’ infidelity in the most public way possible, but also having to face the emotional and physical consequences it may carry for their own lives and health.

For now, the “Nanjing Sister Hong” case is already one of the most talked-about topics on Chinese social media this year — the source of endless memes and AI-generated parodies. The story has grown so large that people are even joking that Trump was one of his secret visitors (see AI meme).

There are even memes about the “Sister Hong starter kit” and others mocking the man who brought half a bottle of cooking oil.

Some joked that “Sister Hong” bears an uncanny resemblance to well-known Chinese political commentator Hu Xijin.

These jokes probably won’t help anyone much, but they’re an inevitable product of China’s meme machine. Still, they shine a bit of light on a topic of which many sides will inevitably remain in the dark for a long time to come.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

PS I mentioned Eileen Yuk-ha Tsang here as one of the scholars focusing on Chinese transgender sex workers. Coincidentally, her new book Unlocking the Red Closet: Gay Male Sex Workers in China is coming out on July 29.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Online Debates About China’s Train Traditions: No More Instant Noodles or Cigarette Breaks?

China Trend Watch: From Lhasa to Labubu

Dialogues Across Time: Remembering War in a New China

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

The Rising Online Movement for Smoke-Free Public Spaces in China

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral1 month ago

China Memes & Viral1 month agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature10 months ago

China Books & Literature10 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Society11 months ago

China Society11 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China Insight4 months ago

China Insight4 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal