China Insight

Top 10 Buzzwords in Chinese Online Media 2019

From blockchain to hardcore, this is an overview of China’s media top buzzwords over the past year.

Published

6 years agoon

By

Jialing Xie

Some of the expressions and idioms that have been buzzing in Chinese media the past year. What’s on Weibo’s Jialing Xie explains.

Last year, we listed China’s “top ten buzzwords” for you (link), giving an overview of some noteworthy expressions on Chinese social media and in the media in 2018. Recently, the chief editor of the magazine Yǎowén Jiáozì (咬文嚼字) has again announced the “top ten buzzwords” in China of the past year.

Yǎowén Jiáozì, which literally means “to pay excessive attention to wording,” is a monthly publication focused on the Chinese language. Chinese (state) media have been widely propagating the magazine’s selection of the top words and terms of the past year in newspapers and on Chinese online media. The ten terms have also become a topic of discussion on Weibo over the past month, with the topic receiving 290 million views.

We’ve listed them for you here:

1. 文明互鉴 (wénmíng hùjiàn): “Mutual Learning”

- Literal Meaning: “Mutual learning,” “Exchanges and mutual learning among different cultures and civilizations.”

- Original context: This expression can be traced back to the era around and during the Warring States Period (475-221 BC), a time of division, bloody battles, and political chaos. The demands for solutions brought forth a broad range of philosophies and schools. During this time, Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism, Mohism and many others were developed leading to the phenomenon known as the “Contention of a Hundred Schools of Thought.”

- What does it mean now? In 2014, at the 4th summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), Chinese President Xi Jinping put forward a major initiative to convene a conference on dialogue between Asian countries followed by an introduction emphasizing how “diversity spurs interaction among civilizations, which promotes mutual learning.” This sentence and expression were later repeated in speeches during various major events. In May 2019, President Xi once again emphasized the idea during the CICA, making the term pop up across Chinese state media again.

2. 区块链 (qū kuài liàn): “Blockchain”

- Literal Meaning: Blockchain Technology

- Context: “Blockchain” is no longer a new concept since it was first introduced to the public around a decade ago. Development of the malleable blockchain technology has become an important trend in China’s tech market through the years.

- What does it mean now? Blockchain was all the buzz in China over the past year. In early 2019, the Cyberspace Administration of China released the Provisions on the Administration of Blockchain Information Services. In October, President Xi singled out blockchain technology as an important breaking point in developing China’s core innovative technology and emphasized the importance of investing and stepping up research on the standardization of blockchain to increase China’s influence and power in the global arena.

3. 硬核 (yìng hé): “Hardcore”

- Literal Meaning: “Hardcore” – 硬 = hard, 核 = core.

- Context: “Hardcore” is known as the abbreviation for Hardcore Punk, a punk rock music genre originated in Southern California during the late 1970s. The term was later used to reference things of a certain level of complexity, such as “hardcore games” (versus casual games). The term started to mean something along the lines of “terrific” (厉害) or “strict”/”rigid” (刚硬) and in Chinese, started being used in expressions such as “Tiger mom” (硬核妈妈) or “Hardcore game players” (硬核玩家).

- What does it mean now? As the Chinese science fiction blockbuster The Wandering Earth (流浪地球) was categorized as ‘hardcore science fiction’ (硬核科幻), the term ‘hardcore’ resurfaced as a popular word often popping up in (online) conversations.

4. 融梗 (róng gěng): “Mixing up ideas”

- Literal Meaning: “Integrating other people’s ideas into one’s own work” or “integrating punchlines,” “mixing up plots.”

- Context: Over the past two decades, many literary works, including a few by prestigious Chinese writers, have been suspected of plagiarism and triggered heated discussions online — when it comes to drawing inspiration from other art and literary creations, where is the boundary between artistic freedom and plagiarism?

- What does it mean now? Soon after the Chinese movie Better Days (少年的你) came out in October (read more here), the writer of the original novel was accused of plagiarizing parts of Japanese mystery writer Keigo Higashino’s work. Many netizens argued that in the field of online literature, borrowing ideas from others (融梗) is ubiquitous and does not necessarily equate plagiarism because the act (融梗) itself requires original work and creativity. From October to now, the term has become a recurring topic in Chinese media.

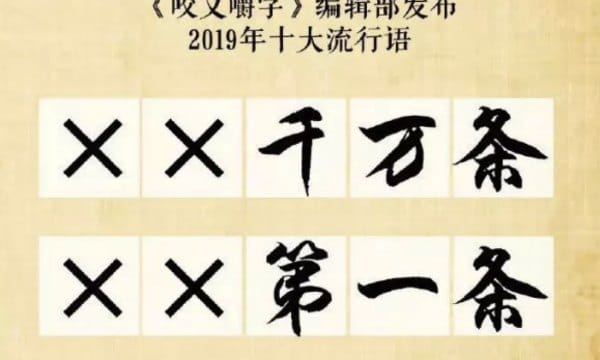

5. “XX 千万条,XX 第一条” (XX qiān wàn tiáo, XX dì yī tiáo): “Out of millions of things,..is the first one”

- Literal Meaning: “Out of ten million things,.. xxx comes first as the rule of thumb.”

- Context: List thinking is prevailing in China; from codes and regulations enacted by the government and laid down by companies, to the way teachers outline their lectures, the usage of “articles” (sometimes used as ‘rules’) or “items” (条) to organize ideas and outline objectives is commonly seen in daily life.

- What does it mean now? This phrase caught people’s attention after appearing in the aforementioned science fiction film The Wandering Earth, where a robot voice reminds a driver of traffic safety in a noteworthy way, saying something along the lines of: “There are thousands of road rules, but safety rules always come first. If you disregard safety, your loved ones will end up in tears.” Despite sounding like a sketch that rhymes poorly in Chinese, the lines stuck around and were later also used by Chinese traffic police across the country. The sentence structure is now also more often applied in various other contexts, for example: “There are thousands of things good for health, but sleep is the most important.”

6. 柠檬精 (níngméng jīng): “Lemon monster”

- Literal Meaning: “Lemon mythical spirit” or “Sour lemon goblin”

- Context: In ancient Chinese superstitions, it’s believed that animals and non-living objects may have the potential to grow into something with spiritual and immortal characteristics if meeting certain criteria. One of the criteria is to be around long enough, usually hundreds of years – if not thousands. For instance, in the classical work Journey to the West (西游记), the four main characters except Tang Sanzang are all spiritual beings derived from animal prototypes.

- What does it mean now? Lemon tastes sour (酸), which is often used to describe the feeling of envy or jealousy. When lemon becomes a spiritual being, it basically means the lemon has reached the ultimate stage of being a lemon and maximized its characteristics such as being terribly sour. The phrase is used to deride those who feel envious of others’ possession and achievement. Lately, the word is more often seen in a self deprecating humoristic context. For instance, when someone says “I’m a lemon jing now/I feel sour now( 我柠檬精了/我酸了)”, instead of expressing envy towards others, it’s more about acknowledging others more advantageous position compared to one’s own.

7. The 996 work schedule

- Literal Meaning: 996 working hour system

- Context: 996 is a work schedule commonly practiced by many companies in the internet and tech industry in China. With the 996 schedule, employees are required to work from 9 am to 9 pm, 6 days per week.

- What does it mean now? In April 2019, Jack Ma, the co-founder and former executive chairman of Alibaba Group, commented on 996 during an internal meeting with Alibaba employees. Ma’s comments seemed to justify how companies and employees can both benefit from the work schedule, however, the comments quickly triggered criticism after widely circulating online for allegedly violating of the Labour Law of the People’s Republic of China.

8. “我太难(南)了” (wǒ tài nán le): “Life is so hard for me”

- Literal Meaning: “I’m feeling uneasy” or “life is so hard for me”

- Context: The phrase originated from a 10-second video self-posted by a user on video-sharing site Kuaishou earlier in 2019. As the video begins, the user – an older Chinese guy – says to the camera: “I’m feeling uneasy…” followed by sad music. He then continues to say “Lao tie [bro/guys], (I) have been under a lot of stress lately.” The video, in which the man dramatically drops his head in his hands and seems to cry without tears, quickly went viral. The phrase “I’m feeling uneasy” was quickly adopted and applied in daily conversations.

- What does it mean now? The broad circulation of this phrase on the internet reflects that the uneasy feeling about life is relatable to many people. Acknowledging the stress in a self-deprecating humorous tone is in itself a way of relieving stress. To add a sense of humor to this phrase, many replace the initial character “难” (nán, adj. difficult) with “南” (nán, adj.& n. south), which is believed to be taken from the mahjong tile “南风”(south wind).

9. “我不要你觉得,我要我觉得” (wǒ bùyào nǐ juédé, wǒ yào wǒ juédé): “I don’t want to know what you think, I only care about what I think”

- Literal Meaning: “I don’t want to know what you think, I only care about what I think.”

- Context: The line was taken from Xiaoming Huang, one of the guests in the third season of the entertainment TV show “Chinese Restaurant”, which was broadcasted in the summer of 2019. In the show, Huang, who took the role as the manager of the restaurant, is self-centered, and often disregards the opinions of others in matters such as menu ideas or pricing, showing his blind self-confidence and arrogance. In addition to this line, Huang’s frequently used language includes “There is no need to discuss this matter”, “Listen to me, I have the final say” and so on, and it spread quickly on the internet.

- What does it mean now? The popularity of this line reflects people’s ridicule and resentment against arrogant and dominant personalities.

10. 霸凌主义 (bàlíng zhǔyì): “Bully-ism”

- Literal Meaning: “Bully-ism”

- Context: The word 霸凌 (bàlíng) comes from the English word “bully.” Here, it refers to bullying other countries in the face of conflicts between nations.

- What does it mean now? As the trade conflict between the US and China was ongoing in 2019, many believed that the current government administration of the United States has been handling international affairs in almost a bullying manner. The slogan “America First” is also often perceived as a declaration in front of the entire world that the interests of the United States come first. As a buzzword, “bullyism” has come to be used by Chinese media in the context of international affairs.

By Jialing Xie

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2020 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Jialing is a Baruch College Business School graduate and a former student at the Beijing University of Technology. She currently works in the US-China business development industry in the San Francisco Bay Area. With a passion for literature and humanity studies, Jialing aims to deepen the general understanding of developments in contemporary China.

You may like

China Insight

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

“You think we’re scared of you? It’s not like we haven’t been to jail before.”

Published

2 months agoon

August 6, 2025

These days have been filled with tension and anger in the city of Jiangyou (江油市), Sichuan, after a rare, large-scale protest broke out following public outrage over a severe bullying incident and how it was handled.

The bullying incident at the center of this story happened outside school premises in Mianyang on the afternoon of July 22. Footage of the assault, recorded by bystanders at the scene, began circulating widely online on August 2, sparking widespread outrage among concerned netizens, many of them worried parents.

The violent altercation involved three girls between the ages of 13 and 15 who ganged up on another minor, a 14-year-old girl named Lai (赖).

After Lai and a 15-year-old girl named Liu (刘) reportedly had a dispute, Liu gathered two of her friends—the 13-year-old also named Liu (刘) and a 14-year-old named Peng (彭)—to gang up on Lai.

The three underage girls lured Lai to an abandoned building, where they subjected her to hours of verbal and physical violence. The footage showed how they took turns in kicking, slapping, and pushing her.

At one point, after Lai said she would call the police, one of the bullies yelled: “You think we’re scared of you? It’s not like we haven’t been to jail before. I’ve been in more than ten times—it doesn’t even take 20 minutes to get out” (“你以为我们会怕你吗?又不是没进去过,我都进去十多次了,没二十分钟就出来了”).

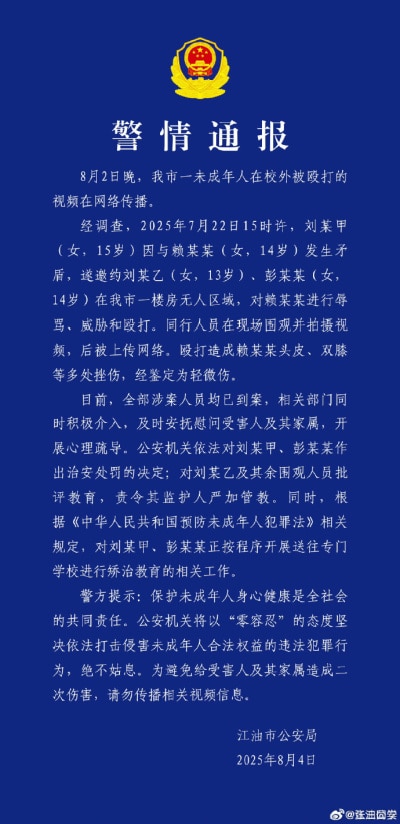

That same night, the incident was reported to police. It took authorities until August 2 to bring in all involved parties for questioning, and a police report was issued on the morning of Monday, August 4.

Police report by Jiangyou Public Security Bureau, confirming the details of the incident and the (legal) consequences for the attackers.

Two of the girls (the 15- and 14-year-old) were given administrative penalties and will be sent to a specialized correctional school. The younger Liu and other bystanders were formally reprimanded.

“Parents Speak Out for the Bullied Girl”

The way the incident was handled—not just the relatively late official report, but mostly the perceived lenient punishment—triggered anger online.

Many people who had seen the video responded emotionally and felt that the underage girls should be stripped of their rights to take their exams, and that the bullying incident should forever haunt them in the same way it will undoubtedly haunt their victim.

Especially the phrase “It’s not like I haven’t been taken in [to jail] before” struck a chord, as it showed just how calculated the bullies were—and how, by counting on the leniency of the Chinese judicial system for minors, they made the system complicit in their determination to turn those hours into a living hell for Lai.

China has been dealing with an epidemic of school violence for years. In 2016, Chinese netizens were already urging authorities to address the problem of extreme bullying in schools, partly because minors under the age of 16 rarely face criminal punishment for their actions.

Since 2021, children between the ages of 12 and 14 can be held criminally responsible for extreme and cruel cases resulting in death or disability—but their legal prosecution must first be approved by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP).

It has not done much to stop the violence.

Discussions around extreme bullying like this have repeatedly flared up over the years, such as in 2020, when a 15-year-old schoolboy named Yuan (袁) in Shaanxi was fatally beaten and buried by a group of minors.

Last year, a young boy named Wang Ziyao (王子耀) was killed by three classmates after suffering years of bullying. His body was found in a greenhouse just 100 meters from the home of one of the suspects, and the case shocked and enraged local residents.

But the problem is widespread among girls, too.

In 2016, we already reported on how so-called ‘campus violence videos’ (校园暴力视频) had become a concerning trend. In these kinds of videos—often showing multiple bullies beating up a single victim on camera—it’s not uncommon to see girls as the aggressors.

Girls often form cliques to gang up on a victim to show that they are in control or to gain popularity. They also tend to be more inclined than boys to make cruel jokes or stage pranks meant to embarrass or humiliate their target. This may partly explain why there seem to be more campus violence videos on Chinese social media showing girls bullying girls than boys bullying boys.

In the case of Lai, she appears to have been particularly vulnerable. One of her relatives posted online that her mother is deaf and mute, and her father allegedly is disabled. This fact may have contributed to why Lai was repeatedly targeted and bullied by the same group of girls, who reportedly took away her phone and socially isolated her at school.

In response to the incident, netizens started posting the hashtag “Parents Speak Up for the Bullied Girl” (“#家长们为被霸凌女孩发声#), not only to support Lai and her family, but to demand harsher punishments for school bullies and for stricter crackdown on this nationwide problem.

From Online Anger to Offline Protest

While many people spoke out for Lai online, hundreds also wanted to show up for her in person.

On August 4, dozens of people gathered in front of the Jiangyou Municipal Government building (江油市人民政府) to demand justice and support Lai’s parents, who had come to express their grievances to the authorities—at one point even bowing to the ground in a plea for justice to be served for their daughter.

Footage and images circulating on social media showing the parents of Lai, the victim, bowing on the ground to demand justice from authorities.

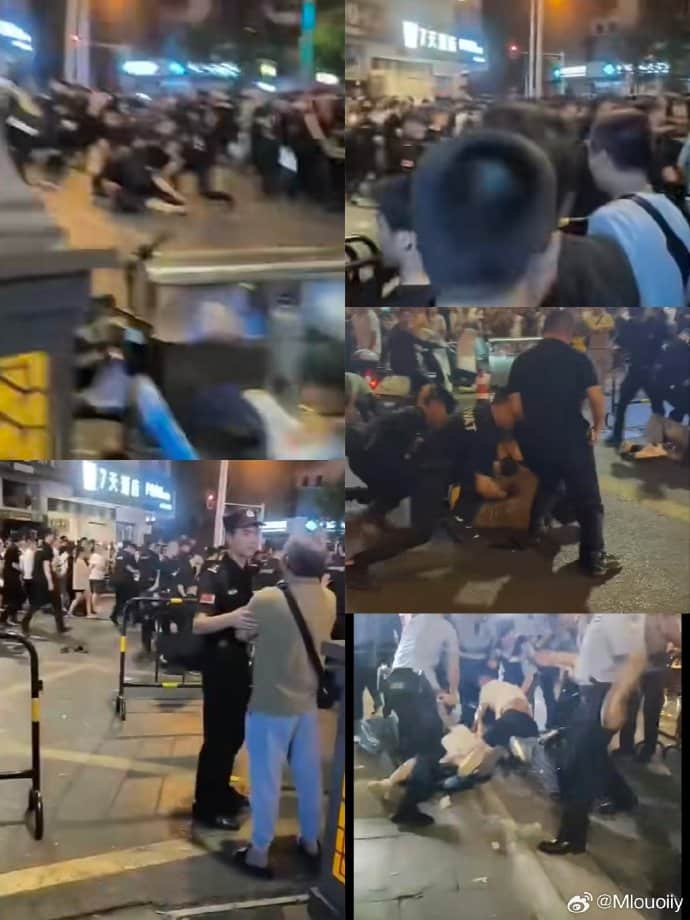

As the crowd grew larger, tensions escalated, eventually leading to clashes between protesters and police.

The arrests at the scene did little to ease the situation. As night fell, the mood grew increasingly grim, and some protesters began throwing objects at the police.

Images of the protest, posted on Weibo.

Near the east section of Shixian Road (诗仙路东段), more people gathered. Hundreds of individuals filming and livestreaming captured footage of the police crackdown—officers beating protesters, dragging them away, and deploying pepper spray.

Netizens’ digital artwork about the bullying incident, the parents’ grievances, and the public protest and its crackdown in Jiangyou. Shared by 程Clarence.

Although the protests briefly gained traction on social media and became a trending topic on Weibo, the search term was soon removed from the platform’s trending list.

Lasting Mental Scars

On Tuesday, August 5, several topics related to the Jiangyou bullying incident began trending again on Chinese social media.

On the short video app Kuaishou, a collective demand for justice surged to the number one spot, under the tag “A large number of Jiangyou parents demand justice for the victim” (江油大批家长为受害学生讨公道).

As of now, none of the perpetrators’ families have come forward to apologize.

As for Lai—according to the latest reports, she did not suffer serious physical injuries from the bullying incident, but according to her own parents, the mental scars will last. She will need continued mental health support and counseling going forward.

Although many posts about the incident and the ensuing protests have been taken offline, ‘Jiangyou’s Bullying Incident’ has already become one more case in the growing list of brutal school bullying incidents that have surfaced on Chinese social media in recent years. The heat of local anger may fade over time, but the rising number of such cases continues to fuel public frustration nationwide—especially if local authorities fail to do more to address and prevent school bullying.

“Not being able to protect our children, that’s a disgrace to our schools and the police,” one commenter wrote: “I want to thank all those mothers who have raised their voices for the bullied child. Each of us must say no to bullies, and we must do all we can to stop them. I hope the lawmakers agree.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

The Secret Life of Monks: Shi Yongxin’s Shaolin Scandal Casts a Shadow on Monastic Integrity

“To put it bluntly, temples have been places of deception, corruption, opportunism, and exploitation since ancient times.”

Published

2 months agoon

July 28, 2025

This week, news about a well-known Chinese monk going off the Buddhist path has triggered many discussions on Chinese social media.

The story revolves around Shi Yongxin (释永信), the head monk at China’s famous Shaolin Temple (少林寺) in Dengfeng, Henan. Shi is suspected of embezzlement of temple funds and illicit relationships, and is currently under investigation.

In recent days, wild rumors have been circulating online claiming that Shi fled to the United States after being exposed. On July 26, a supposed “police bulletin” began circulating, alleging that Shi Yongxin had attempted to leave the country with seven lovers, 21 children, and six temple staff. It also claimed he was stopped by authorities before exiting China, that he had secretly obtained U.S. citizenship a decade ago, and that he had misused donations and assumed fake identities.

Although that specific report has since been refuted by Chinese official media, it quickly became clear that there was real fire behind all that smoke.

The report that circulated online and was later confirmed to be fake

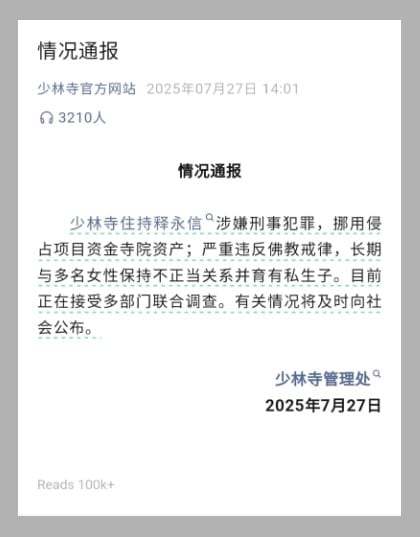

Because despite all the sensationalized gossip (some posts even claimed Shi had 174 illegitimate children!), what’s certain is that Shi Yongxin seriously crossed the line. On July 27, 2025, the Shaolin Temple Management Office (少林寺管理处) issued an official statement through its verified channels, including its WeChat account. The statement read:

The report that circulated online and was later confirmed to be fake.

Shi Yongxin, the Abbot of Shaolin Temple, is suspected of criminal offenses, including misappropriating and taking project funds and temple assets. He seriously violated Buddhist discipline, maintained improper relationships with multiple women over a long period and fathered illegitimate children. He is currently under joint investigation by multiple departments. Relevant information will be made public in due course.

Shaolin Temple Management Office

July 27, 2025

China’s Buddhist Association (中国佛教协会) also released a statement on July 28, in which it stated that, in coordination with the Henan Provincial Buddhist Association (河南省佛教协会), Shi Yongxin has been officially stripped of his monastic status.

Various Chinese media sources report that Shi Yongxin was taken away by police on Friday, July 25. Chinese media outlet Caixin suggests that it must not have come as a complete surprise, since Shi had allegedly already been restricted from leaving the country since around the Spring Festival period (late January 2025) (#释永信春节前后已被限制出境#).

About Shi Yongxin

Shi Yongxin is not just any abbot. He’s the abbot of the Shaolin Monastery (少林寺), which is one of the most famous Buddhist temples in the world and is known as the birthplace of Shaolin Kung Fu. The temple was founded in 495 CE. Besides being a Buddhist monastery, it also operates as a popular tourist attraction, a kung fu school, and a cultural brand.

Shi has been running the monastery for 38 years, a fact that also went trending on Weibo these days (#释永信已全面主持少林寺38年#, 140 million views by Monday).

Shi Yongxin is the monastic name of Liu Yingcheng (刘应成), born in Yinshang county in Fuyang, Anhui, in 1965. He came to Shaolin Temple in 1981 and became a disciple of abbot Shi Xingzheng (释行正), who passed away in 1987. Shi Yongxin then followed in his footsteps and managed the temple affairs. He formally became head monk in 1999.

Moreover, Shi Yongxin reportedly served as President of the Henan Provincial Buddhist Association since 1998 and as Vice President of the Buddhist Association of China since 2002.

Shi Yongxin, photos via Weibo.

Shi Yongxin was thus an incredibly powerful figure—not only because of the decades he spent overseeing temple affairs, but also due to his influence within public, institutional, and religious spheres.

Holding such a visible role, Shi Yongxin (释永信) also had (or has—though it’s unlikely he’ll ever post again) a Weibo account with over 882,000 followers (@释永信师父). His last post, made on July 24, was a Buddhist text about the ‘Pure Land’ (净土)—a realm said to make the path toward enlightenment easier.

That post has since attracted hundreds of replies. While some devoted followers express disbelief over the scandal, many others respond with cynicism, questioning whether anything about Buddhism remains truly ‘pure.’

One widely shared post shows an artist sitting in front of a painting of Shi Yongxin, writing, “Worked on this painting for six months, just finished late last night—feels like the sky’s collapsed.” The second picture, posted by someone else, says, “Just change it a bit.”

One aspect of the scandal fueling online discussions is the fact that Shi Yongxin had led the monastery for so long. Rumors about his “chaotic private life” and unethical behavior surfaced years ago, going back to at least 2015 (#释永信10年前就曾被举报私生活混乱#; #释永信曾被举报向弟子索要供养钱#). One of the questions now echoing across social media is: why wasn’t he held accountable sooner? “Who was protecting him?”

“The Tip of the Iceberg”

The Shi Yongxin scandal does not just hurt the reputation and cultural brand of the Shaolin Monastery; it also damages a certain image of Buddhist monks as a collective of people with true faith and integrity.

According to well-known knowledge blogger Pingyuan Gongzi Zhao Sheng (@平原公子赵胜), many people’s understanding of abbots or Buddhist masters (“方丈大师们”) is flawed, since it’s generally believed they attained their high positions within the monasteries due to their moral virtue or deep understanding of Buddhism. In reality, Zhao Sheng argues, these individuals often rise to power because they are skilled at earning money and gaining influence.

“To put it bluntly,” Zhao Sheng writes, “temples have been places of deception, corruption, opportunism, and exploitation since ancient times.”

The blogger argues that much of the influence and power of Buddhist masters was stripped away under Mao Zedong, but that some new famous monks rose in the 1980s, using their skills and connections to rebuild temples and turn them into thriving enterprises.

“If you want to find a few people in temples who truly have faith, who truly have personal integrity, and who are truly dedicated to saving all living things, it’s not that they don’t exist—but it’s rather difficult, like finding a needle in a haystack,” Zhao Sheng wrote.

Some commenters suggest that Shi Yongxin is just the tip of the iceberg (“冰山一角”). They believe that if someone as influential as him can be involved in such misconduct—despite whistleblowers having tried to expose him for over a decade—there must be many more cases of power abuse and corruption within China’s monasteries.

“I previously donated money to the temple,” one commenter on Xiaohongshu wrote: “Although it wasn’t much, it does make me a bit uncomfortable now.”

Another person posted that the Shi Yongxin scandal gave them a sense of despair.

Some older posts about the extravagant lifestyles of head monks — including their luxury cars — have also resurfaced online and are once again making the rounds, suggesting that netizens are actively revisiting other potential instances of misconduct within the monastic world.

Abbot Guangquan Fashi (光泉法师) with a Ferrari California T, Kaihao Fashi (开豪法师) with a Porsche Panamera, Shi Yongxin (释永信) linked to an Audi Q7, and Huiqing (慧庆) and a BMW 7 Series.

One image that resurfaced online shows Shi Yongxin—allegedly driving an Audi Q7—alongside other abbots, such as Guangquan Fashi (光泉法师), the head monk of Lingyin Temple (灵隐寺), who is associated with a Ferrari.

More images like these are now circulating, as people delve into the ‘secret lives of monks’ beyond the spiritual, shifting focus to their material lives instead.

Monks from major temples, including Qin Shangshi (钦尚师) of Famen Temple, E’erdeni (鄂尔德尼) of Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, Yin Le (印乐) of Baima Temple, and Huiqing (慧庆) of Baishou Temple, are rumored to be associated with high-end cars like BMWs, a Porsche Cayenne, and a Range Rover.

While the results of the investigation into Shi Yongxin are still pending, many netizens are already looking beyond him. One person writes: “Are you realizing now? It’s not just Shaolin Temple that has money, other temples aren’t exactly short on money either.”

Another person wonders: “Are the monks in today’s temples actually still truly devoted to spiritual practice at all?”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

Nanchang Crowd Confuses Fan for Knife — Man Kicked Down and Taken Away

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

China’s National Day Holiday Hit: Jingdezhen’s “Chicken Chop Bro”

Evil Unbound (731): How a Chinese Anti-Japanese War Film Backfired

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Rising Online Movement for Smoke-Free Public Spaces in China

China Trend Watch: Pagoda Fruit Backlash, Tiananmen Parade Drill & Alipay Outage (Aug 11–12)

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral3 months ago

China Memes & Viral3 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature11 months ago

China Books & Literature11 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral9 months ago

China Memes & Viral9 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained