China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Top 10 Most Popular Smartphones in China (Fall/Winter 2020)

From OPPO to iPhone, these are the most popular smartphones in China at the moment.

Published

5 years agoon

These are the most popular smartphone brands and devices in China right now. An overview by What’s on Weibo.

It’s been a while since What’s on Weibo last did a top 10 of most popular / top-rated smartphones in China (link). Because the latest smartphone models have been attracting a lot of attention on Chinese social media recently, it is high time for another update.

Apple’s iPhone 12 series, Huawei’s Mate 40, and Samsung’s Note 20 series are among the most discussed smartphones this season, but there are so many more devices gaining popularity over the past few weeks and months.

In previous years, there was a strong focus on bezel-less screens, trendy designs, and selfie camera quality. Now, there’s a shifting focus on 5G, (8K) video and multiple cameras, fast charging technology, and overall fast performance. All models in this list are 5G ready.

For this list, we loosely follow the popularity rankings of Zol, a leading IT portal website in China that compiles its lists based on the data provided by its own Internet Consumer Research Center (ZDC 互联网消费调研中心).

Since its top ten rankings are changing every day, we also take into account how much views and clicks these latest models are receiving on social media site Weibo. If multiple models of the same series occur in different places in the official rankings, we’ve put them under one ranking together (e.g. the OPPO Reno 4 SE and the OPPO Reno 4 Pro, or the Huawei Nova 7 Pro and Huawei Mate 40).

China’s most popular smartphone brands at this moment are OPPO, Vivo, Huawei, Apple, and Honor.

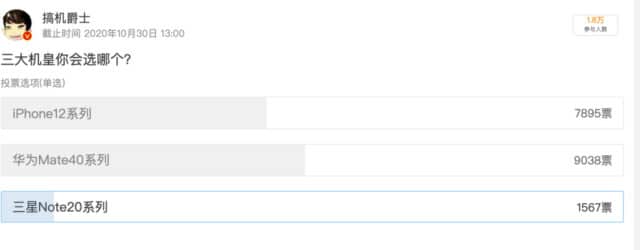

When popular Weibo blogger Gǎojī Juéshì (@搞机爵士,2.1 million fans) recently asked his followers which flagship phone of the moment they would choose – Apple’s iPhone 12, Huawei’s Mate 40, or Samsung’s Note 20 – a majority of 49% of respondents voted for the Huawei brand. 43% voted Apple, and 8% voted Samsung.

Although the number one of this list, the OPPO Reno4, has consistently been holding the number one spot in last week’s ranking, the other models are shifting places in the top rankings, so this is not an ‘official’ top ranking list, just one that is compiled by us following the latest trends.

1. OPPO RENO4 SE & PRO (8GB/128GB/5G)

OPPO is a Guangdong-based brand officially launched in 2004. It is mainly known for targeting China’s young consumers with trendy designs and smart marketing. Its product quality combined with successful online marketing has made the brand super popular throughout the years.

For the Reno4, TF Boys member Wang Junkai (@王俊凯, aka Karry Wang) who has nearly 79 million fans on Weibo, is the OPPO brand ambassador promoting this model. One Weibo post by Wang promoting the Reno4 SE received over 735,000 comments and one million likes.

The OPPO Reno4 SE was officially launched in China in late September of 2020 and is not yet available for the international market.

The Reno4 SE has a 6.43-inch AMOLED display (1080 x 2400 pixels) and comes with a triple rear camera setup (48MP, 8MP, 2MP). Noteworthy is its 32MP (!) selfie camera.

It comes with 8GB of RAM and 128GB storage (no expandable storage). Some of the Reno4 SE’s other highlights include the 65W fast charging and 5G connectivity support. The smartphone runs Android 10 OS, topped with OPPO’s own ColorOS 7.2.

On Weibo, the OPPO Reno4 SE hashtag (#OPPO小光芒Reno4 SE#) has 710 million views at the time of writing.

The Oppo Reno 4 Pro is also listed in Zol’s top ranking list, ranking 8 at the time of writing. This model is slightly bigger, with a Super AMOLED display and extra memory card slot. It also has NFC and a more high-end camera. It is priced around ¥3799 ($566).

The OPPO Reno4 SE is priced at ¥2499 ($373) at JD.com and Tmall, and is one of the cheaper devices in this list – its price is nowhere near that of the Samsung Note 20 Ultra or the iPhone 12, making it much more affordable to many. The Reno4 SE smartphone comes in three color options: Super Flash Black, Super Flash Blue, and Super Flash White.

2. VIVO X50 PRO (8GB/128GB/5G)

At time of writing, not only does the Vivo x50 Pro hold the number two spot in the top popular smartphone rankings, but Vivo is also ranking as the second most popular smartphone brand in China at this moment (OPPO being number one).

Like OPPO, Vivo is another Chinese domestic brand that has gained worldwide success, first entering the market in 2009. Its headquarters are based in Dongguan, Guangdong.

When it comes to marketing its smartphones, Vivo has really focused on camera quality over the past years. Its earlier Vivo x27 device was launched as a “night photo wonder tool,” and for the Vivo x50 Pro, there is again this focus on “redefined photography,” camera light sensitivity and stabilization.

The main camera is a 48MP “Gimbal” main camera, accompanied by a 13MP, 50 mm prime portrait camera, a wide-angle lens, and 60 x optical zoom camera.

Collaborating with state media outlet CCTV, there recently was a Golden Week social media promotion of the device showing beautiful night photos from the Summer Palace.

The Vivo x50 Pro was launched in June of 2020. The slim device has a 6.56 inch AMOLED display, 1080 x 2376 pixels. Due to its powerful processor, 90 Hz high refresh & 180 Hz touch sampling rate, and gaming-centric features, the Vivo x50 Pro will also be appreciated by gamers.

By now, the Weibo hashtag associated with the Vivo x50 series (#vivo X50系列 超感光微云台#) has gained over 1.7 billion views.

Many people on social media also share their own photos shot with their Vivo x50 Pro.

The Vivo x50 Pro 5G is priced at ¥3998 ($596) at e-commerce sites such as JD.com. It comes in Dark Blue and Light Blue colors.

3. Huawei Nova 7 Pro (8GB/128GB/5G) and Huawei Mate 40 (8B/128GB/5G)

Both the Huawei Nova 7 Pro and Huawei Mate 40 are in the top ranking lists of this moment. Huawei also ranks number three in official top-ranking smartphone brand lists of this moment, coming in before Apple in popularity.

The Huawei Nova 7 was released in April of 2020, and the Huawei Mate 40 series was released in China on October 30 with the Mate 40, Mate 40 Pro, and Mate 40 Pro+ (we’ll update this when more news comes out). The Mate 40 and Mate 40 Pro were previously on pre-order sale, and reportedly sold out within 30 seconds. The Mate 40, which ranks highest in popularity at this time, is an ‘entry-level’ device within the Mate 40 series.

The Huawei Mate 40 comes with a 6.76-inch Flex OLED display with a 2722 x 1344 pixels screen resolution, a 90Hz refresh rate, and a 240Hz touch sampling rate. There’s been a lot of hype surrounding the Huawei Mate 40 since it was said it would come with “a feature” that was still to be disclosed – which turned out to be the digital yuan wallet feature.

The older Huawei Nova7 Pro is a dual-sim device. It has a 6.57-inch display (1080 x 2340) and a 64MP + 8MP + 8MP + 2MP rear camera, the front camera being 32MP + 8MP.

The Weibo hashtag for the Huawei Nova 7 series (#华为nova7#) has nearly 2 billion views on Weibo at time of writing, with the Huawei Mate 40 garnering 1.2 billion views on its hashtag page (#华为Mate40#).

The Nova 7 pro is priced at ¥3699 ($550). The Nova 7 Pro was released in the colors Midnight Black, Silver, Forest Green, Midsummer Purple, and Honey Red. The Mate40 is ¥4999 ($745).

4. Samsung Galaxy Note 20 Ultra (12GB/256GB/5G)

Together with Apple, Samsung currently is among the most popular smartphone brands in the PRC that is not made-in-China. The brand seems to have been able to win back consumer’s trust after previous problems with overheating and exploding batteries.

The Galaxy Note 20 and Note 20 Ultra were launched in summer 2020. Both are top-notch devices, with a Snapdragon 865 Plus processor and a 10-megapixel selfie camera, and of course, the Note’s landmark ‘S Pen’ including new gestures.

What makes the ‘Ultra’ device different from the Galaxy Note 20 is its Gorilla Glass Victus back (which is more durable and has better drop resistance), its AMOLED screen, 108-megapixel camera, and its microSD card slot – making it possible to expand the 256GB storage with a Micro-SD of up to 1TB. Despite the price difference, the aforementioned features make it understandable that the ‘Ultra’ is a more popular choice over the Samsung Note 20 device.

The Galaxy Note 20 Ultra shoots 8K video, the highest-resolution video recording available. It is also the first Note with a 120 Hz refresh rate display. For reference: a standard smartphone display usually refreshes at 60 times per second, or at 60 Hz. This high refresh rate means you get smoother animations and navigation. The device also has a 240Hz touch sampling rate (the frequency at which the display polls for touches on the display).

With its 6.9 inch (1440 x 3088) display, the Note 20 Ultra is the biggest phone on this list. It weighs 208 grams.

On Weibo, the hashtag “Samsung Note 20” (#三星note20#) has over 330 million views. The Samsung Note 5G Ultra is available in bronze, white, and black, and is available from ¥9199 ($1370), making it the most expensive phone on this list. Although many people on Weibo say they do like this phone, the high price is an obstacle, with some saying: “The price just kills me.”

5. OnePlus 8Pro and 8T (8GB/128 GB/5G)

“Never settle” is the slogan used by OnePlus, a Shenzhen-based Chinese smartphone manufacturer founded by Pete Lau and Carl Pei in December 2013.

Both the OnePlus8Pro and the cheaper 8T models are ranking high in current top listings. The 8T was released in October of this year, while the Pro version came out earlier in April.

Both phones come with Dual-SIM, AMOLED display (120 Hz refresh rate), Gorilla Glass 5 front and back, 4K video, stereo speakers, NFC, and 48MP main cameras.

The Pro is the bigger phone – with its 6.79 inch screen and 199 grams, it comes quite close to the Samsung Note 20 Ultra. It also has a slightly more advanced quad camera.

The OnePlus 8 series hashtag (#一加8#) currently has some 1,3 billion views on Weibo.

The OnePlus 8 Pro received quite some attention on social media earlier this year, when it turned out that its ‘Photochrom’ color filter, using infrared sensors, could see through some materials, such as plastic.

The OnePlus 8 Pro 5G is priced at ¥5399 ($805), the OnePlus 8T model is priced at ¥3399 ($507).

6. iQOO 5 (12GB/128GB/5G)

The iQOO is not well-known outside of China, but it is actually a sub-brand of Vivo. iQOO is owned by the BKK Group (步步高), which also owns OPPO, OnePlus, and RealMe.

The iQOO 5 was released in August of this year. Its AMOLED display is about the same size as the OnePlus8T (6.56 inch), they both have 120Hz refresh rate screen, dual SIM, and the two phones actually seem to be competitors in multiple ways, although the iQOO is the pricier option.

The iQOO has a 16-megapixel selfie camera, its rear camera is a 50MP, along with a 13MP ultra-wide angle and 13MP depth sensor. It has 8K video recording.

On social media, the iQOO is mainly marketed as a ‘fast phone’ – and in doing so (#iQOO 5 超能竞速#) it has reached 370 million views on its hashtag page at time of writing.

The iQOO 5 is priced at ¥4298 ($640) and comes in blue or grey.

7. OPPO FIND X2 PRO (12GB/256GB/5G)

The OPPO Find X2 Pro was already launched in March of 2020 and yet it still is one of the most popular phones of the moment in China – even though it is also one of the more expensive devices in this list.

With its 6.7 inch display, it is just as big as the Apple iPhone 12 Pro Max, and in some ways it could be argued that it is a real competitor. With its 48 MP/13MP/48MP main camera and 32MP selfie camera, and, among others, stereo speakers and fast-charging features, it’s a fancy device.

Some reviewers argue the design is better than the Apple iPhone Pro, and that its display is more impressive.

The OPPO Find X2 series hashtag page (#OPPO Find X2#) has over 1.8 billion views on Weibo.

Priced at ¥5999 ($895), the OPPO Find x2 Pro comes in Black, Orange, Light Grey, Green, Lamborghini Edition, with the orange/grey/green editions all made from (vegan) leather instead of glass or plastic.

8. IPHONE 12 (4GB/128GB/5G) & IPHONE 12 PRO MAX (6GB/128GB/5G)

Despite its relatively high price, the iPhone 12 is still very popular in China – but at time of writing, still lags behind a bit in the top-ranking lists, and does not come up in the top five lists (yet).

The Apple iPhone 12 and the Pro Max were both announced on October 13, with the iPhone 12 launched later in October, along with the Apple iPhone 12 Pro. The Apple iPhone 12 Mini, like the Pro Max, is yet to be released.

The iPhone 12 is the smallest and lightest model of the 12 / 12 Pro / 12 Pro Max trio. It has a 6.1 inch (1170 x 2532) Super Retina XDR display, which is also among the smaller device displays in this list. The phone is also marketed as “the world’s smallest, thinnest, lightest 5G phone” with the “best iPhone display ever.” It comes with a dual 12-megapixel camera on the rear and a 12-megapixel selfie camera on the front.

It’s actually hard to track the views on the iPhone 12 series on Weibo since there are so many different hashtags relating to iPhone12 news – this in itself gives an idea of how popular this phone is. The most used “iPhone 12” hashtag (#iphone12#) has a staggering 9 billion views.

The iPhone 12 comes in the Black, White, Red, Green, Blue colors, and is currently priced at ¥6299 ($940) in China. The 12 Pro Max, with a giant 6.7-inch display and fancier camera, is priced at ¥9299 ($1387) – making it the most expensive phone on this list.

9. HONOR X10 & HONOR 30 (6GB/128GB/5G)

Together with the super popular OPPO’s Reno 4 SE, the Honor X10 and Honor 30 are among the more affordable devices on this list, with the X10 being slightly more popular than the more expensive Honor 30.

Honor is perhaps not as well-known outside of China as other Chinese smartphone brands are. Honor (荣耀), established in 2013, is the budget-friendly sister of the Huawei brand. The company’s sub-brand has been doing very well over the past years. Honor focuses on great value for money, and in doing so, targets younger consumers, not just with its relatively low prices, but also with its trendy designs.

The Honor X10 5G was released in May of this year, the Honor30 was released a month earlier. Size-wise, display-wise, price-wise, these Honor devices could compete with the newer OPPO Reno 4 device, with many of their specs being similar. Both devices support expandable memory.

The Honor 30 is slightly better than the X10 when it comes to pixel density and CPU speed, but this model also has a better camera setup (40+8+8+2 MP versus 40+8+2 MP).

The X10, however, has a stronger battery (4300mAh) and a bigger screen (6.63 inches).

Honor30 hashtag (#荣耀30#) has garnered 3,5 billion views on Weibo thus far; the X10 is also popular on social media (#荣耀x10#) with 1,1 billion clicks.).

The Honor X10 is priced at ¥2199 ($328). The Honor 30 is ¥2699 ($402).

10. XIAOMI 10 (8GB/128GB)

Since the launch of its first smartphone in 2011, Beijing-brand Xiaomi has become one of the world’s largest smartphone makers.

The Xiaomi 10, released in May 2020, is a dual SIM device that comes with a 6.67-inch (2340 x 1080) AMOLED display with a 90 Hz refresh rate, a strong 4780 mAh battery, and 108+13+2+2 MP rear camera. It also supports 5G and has quick charging, so it’s a very 2020 device. According to Gadgets Now, the Xiaomi 10 “lives up to the hype.”

With over 3,2 billion views on the Xiaomi 10 hashtag page on Weibo (#小米10#), the Xiaomi brand also succeeded to create an online hype earlier this year. Discussions were mostly focused on the model’s camera performance and its screen.

The Xiaomi 10 is priced around ¥3499 ($521), with cheaper deals available. It comes in black, grey, green, and pink.

For clarification, we’ll list the aforementioned devices again, based on pricing, with the most expensive devices coming first. Note that these are the approximate prices for the Chinese market, which might be (very) different outside of China:

1. iPhone 12 Pro Max / ¥9299 ($1387)

2. Samsung Note 20 5G Ultra / ¥9199 ($1370)

3. iPhone 12 / ¥6299 ($940)

4. OPPO Find x2 Pro / ¥5999 ($895)

5. OnePlus 8 Pro 5G / ¥5399 ($805)

6. iQOO 5 / ¥4298 ($640)

7. Vivo x50 Pro 5G / ¥3998 ($596)

8. OPPO Reno4 Pro / ¥3799 ($565)

8. Huawei Nova 7 Pro 5G / ¥3699 ($550)

9. Xiaomi 10 / ¥3499 ($521)

10. OnePlus 8T / ¥3399 ($507)

11. Honor30 / ¥2699 ($402)

12. OPPO Reno4 SE / ¥2499 ($373)

13. Honor x10 / ¥2199 ($328)

By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

NB: This post is not a sponsored post in any way. This article may, however, include affiliate links that at absolutely no additional cost whatsoever to you allows this site to receive a small percentage in case you purchase something after you click.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2020 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform resurfaces in Africa, a new winter hotspot, why Chinese elites ‘run’ to Tokyo, and more.

Published

2 months agoon

November 21, 2025

🌊 Signals — Week 47 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China, Signals highlights slower trends and online currents behind the daily scroll. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Different from the China Trend Watch (check the latest one here if you missed it), this edition, part of the new Signals series, is about the slower side of China’s social media: the recurring themes and underlying shifts that signal broader trends beyond the quick daily headlines. Together with the deeper dives, the three combined aim to give you clear updates and a fuller overview of what’s happening in China’s online conversations & digital spaces.

For the coming two weeks, I’ll be traveling from Beijing to Chongqing and beyond (more on that soon) so please bear with me if my posting frequency dips a little. I’ll be sure to pick it up again soon and will do my best to keep you updated along the way. In the meantime, if you know of a must-try hotpot in Chongqing, please do let me know.

In this newsletter: Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform in Angola, a new winter hotspot, discussions on what happens to your Wechat after you die, why Chinese elites rùn to Tokyo, and more. Let’s dive in.

- 💰 The richest woman in China, according to the latest list by Hurun Research Institute, is the “queen of pharmaceuticals” Zhong Huijuan (钟慧娟) who has accumulated 141 billion yuan (over 19 billion USD). Women account for over 22% of Chinese billionaires (those with more than 5 billion RMB), underscoring China’s globally leading position in producing wealthy female entrepreneurs.

- 🧩 What happens to your WeChat after you die? A user who registered for NetEase Music with a newly reassigned phone number unexpectedly gained access to the late singer Coco Lee’s (李玟) account, as the number had originally belonged to her. The incident has reignited debate over how digital accounts should be handled after death, prompting platforms like NetEase and Tencent to reconsider policies on long-inactive accounts and take stronger measures to protect them.

- 📱 Although millions of viewers swoon over micro-dramas with fantasy storylines where rich, powerful men win over the “girl next door” through money and status, Chinese regulators are now stepping in to curb exaggerated plots featuring the so-called “dominant CEO” (霸道总裁) archetype, signaling stricter oversight for the booming short drama market.

- ☕ A popular Beijing coffee chain calling itself “People’s Cafe” (人民咖啡馆), with its style and logo evoking nationalist visual nostalgia, has changed its name after facing criticism for building its brand – including pricey coffee and merchandise – on Mao era and state-media political connotations. The cafe is now ‘Yachao People’s Cafe’ (要潮人民咖啡馆).

- 👀 Parents were recently shocked to see erotic ads appear on the Chinese nursery rhymes and children’s learning app BabyBus (宝宝巴士), which is meant for kids ages 0–8. BabyBus has since apologized, but the incident has sparked discussions about how to keep children safe from such content.

- 🧧The 2026 holiday schedule has continued to be a big topic of conversation as it includes a 9-day long Spring Festival break (from February 15 to February 23), making it the longest Lunar New Year holiday on record. The move not only gives people more time for family reunions, but also gives a huge boost to the domestic travel industry.

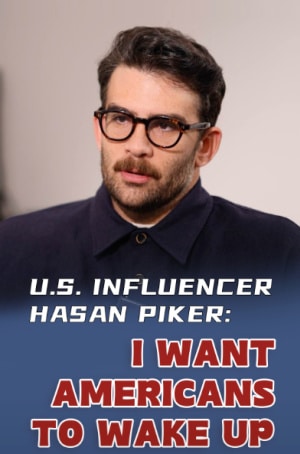

Hasan Piker’s Chinese Tour & The US–China Content Honeymoon

Livestreamer Hasan Piker during his visit to Tiananmen Square flag-rising ceremony.

It’s not time for the end-of-year overviews just yet – but I’ll already say that 2025 was the US–China ‘honeymoon’ year for content creation. It’s when China became “cool,” appealing, and eye-grabbing for young Western social media users, particularly Americans. The recent China trip of the prominent American online streamer Hasan Piker fits into that context.

This left-wing political commentator also known as ‘HasanAbi’ (3 million followers on Twitch, recently profiled by the New York Times) arrived in China for a two-week trip on November 11.

Piker screenshot from the interview with CGTN, published on CGTN.

His visit has been controversial on English-language social media, especially because Piker, known for his criticism of America (which he calls imperialist), has been overly praising China: calling himself “full Chinese,” waving the Chinese flag, joining state media outlet CGTN for an interview on China and the US, and gloating over a first-edition copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao (the Little Red Book). He portrays China as heavily misrepresented in the West and as a country the United States should learn from.

Hasan Piker did an interview with CGTN, posing with Li Jingjing 李菁菁.

During his livestreaming tour, Hasan, who is nicknamed “lemonbro” (柠檬哥) by Chinese netizens, also joined Chinese platforms Bilibili and Xiaohongshu.

But despite all the talk about Piker in the American online media sphere, online conversations, clicks, and views within China are underwhelming. As of now, he has around 24,000 followers on Bilibili, and he’s barely a topic of conversation on mainstream feeds.

Piker’s visit stands in stark contrast to that of American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins), who toured China in March. With lengthy livestreams from Beijing to Chongqing, his popularity exploded in China, where he came to be seen by many as a representative of cultural diplomacy.

IShowspeed in China, March 2025.

IShowSpeed’s success followed another peak moment in online US–China cultural exchange. In January 2025, waves of foreign TikTok users and popular creators migrated to the Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu amid the looming TikTok ban.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against Trump and US policies. In a playful act of political defiance, they downloaded Xiaohongshu to show they weren’t scared of government warnings about Chinese data collection. (For clarity: while TikTok is a made-in-China app, it is not accessible inside mainland China, where Douyin is the domestic version run by the same parent company).

The influx of foreigners — who were quickly nicknamed “TikTok refugees” — soon turned into a moment of cultural celebration. As American creators introduced themselves, Chinese users welcomed them warmly, eager to practice English and teach newcomers how to navigate the app. Discussions about language, culture, and societal differences flourished. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor. It was a rare moment of social media doing what we hope it can do: connect people, build bridges, and replace prejudice with curiosity.

Some of that same enthusiasm was also visible during IShowSpeed’s China tour. Despite the tour inevitably getting entangled with political and commercial interests, much of it was simply about an American boy swept up in the high energy of China’s vibrant cities and everything they offer.

Different from IShowSpeed, who is known for his meme-worthy online presence, Piker is primarily known for his radical political views. His China enthusiasm feels driven less by cultural curiosity and more by his critique of America.

Because of his stances — such as describing the US as a police state — it’s easy for Western critics to accuse him of hypocrisy in praising China, especially after a brief run-in with security police while livestreaming at Tiananmen Square.

Seen in broader context, Piker’s China trip reflects a shift in how China is used in American online discourse.

Before, it was Chinese ‘public intellectuals’ (公知) who praised the US as a ‘lighthouse country’ (灯塔国), a beacon of democracy, to indirectly critique China and promote a Western modernization model. Later, Chinese online influencers showcased their lives abroad to emphasize how much ‘brighter the moon’ was outside China.

In the post-Covid years, the current reversed: Western content creators, from TikTok influencers to political commentators, increasingly use China to make arguments that are fundamentally about America.

Between these cycles, authentic cultural curiosity gets pushed to the sidelines. The TikTok-refugee moment in early January may have been the closest we’ve come in years: a brief window where Chinese and American users met each other with curiosity, camaraderie, and creativity.

Hasan’s tour, in contrast, reflects a newer phase, one where China is increasingly used as a stage for Western political identity rather than a complex and diverse country to understand on its own terms. I think the honeymoon phase is over.

“Liu Sihan, Your School Uniform Ended Up in Angola”: China’s Second-Hand Clothing in Africa

A Chinese school uniform went viral after a Chinese social media user spotted it in Angola.

“Liu Sihan, your schooluniform is hot in Africa” (刘思涵你的校服在非洲火了) is a sentence that unexpectedly trended after a Chinese blogger named Xiao Le (小乐) shared a video of a schoolkid in Angola wearing a Chinese second-hand uniform from Qingdao Xushuilu Primary School, that had the nametag Liu Sihan on it.

The topic sparked discussions about what actually happens to clothing after it’s donated, and many people were surprised to learn how widely Chinese discarded clothing circulates in parts of Africa.

Liu Sihan’s mother, whose daughter is now a 9th grader in Qingdao, had previously donated the uniform to a community clothing donation box (社区旧衣回收箱) after Liu outgrew it. She intended it to help someone in need, never imagining it to travel all the way to Africa.

In light of this story, one netizen shared a video showing a local African market selling all kinds of Chinese school items, including backpacks, and people wearing clothing once belonging to workers for Chinese delivery platforms. “In Africa, you can see school uniforms from all parts of China, and even Meituan and Eleme outfits,” one blogger wrote.

When it comes to second-hand clothing trade, we know much more about Europe–Africa and US–Africa flows than about Chinese exports, and it seems there haven’t been many studies on this specific topic yet. Still, alongside China’s rapid economic transformations, the rise of fast fashion, and the fact that China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of textiles, the country now has an enormous abundance of second-hand clothing.

According to a 2023 study by Wu et al. (link), China still has a long way to go in sustainable clothing disposal. Around 40% of Chinese consumers either keep unwanted clothes at home or throw them away.

But there may be a shift underway. Donation options are expanding quickly, from government bins to brand programs, and from second-hand stores to online platforms that offer at-home pickup.

Chinese social media users posting images of school/work uniforms from China worn by Africans.

As awareness grows around the benefits of donating clothing (reducing waste, supporting sustainability, and the emotional satisfaction of giving), donation rates may rise significantly. The story of Liu Sihan’s uniform, which many found amusing, might even encourage more people to donate. And if that happens, scenes of African children (and adults) wearing Chinese-donated clothes may become much more common than they now are.

Laojunshan: New Hotspot in Cold Winter

Images from Xiaohongshu, 背包里的星子, 旅行定制师小漾

Go to Zibo for BBQ, go to Tianshui for malatang, go to Harbin for the Ice Festival, cycle to Kaifeng for soup dumplings, or head to Dunhuang to ride a camel — over recent years, a number of Chinese domestic destinations have turned into viral hotspots, boosted by online marketing initiatives and Xiaohongshu influencers.

This year, Laojunshan is among the places climbing the trending lists as a must-visit spot for its spectacular snow-covered landscapes that remind many of classical Chinese paintings. Laojunshan (老君山), a scenic mountain in Henan Province, is attracting more domestic tourists for winter excursions.

Xiaohongshu is filled with travel tips: how to get there from Luoyang station (by bus), and the best times of day to catch the snow in perfect light (7–9 AM or around 6–6:30 PM).

With Laojunshan, we see a familiar pattern: local tourism bureaus, state media, and influencers collectively driving new waves of visitors to the area, bringing crucial revenue to local industries during what would otherwise be slower winter months.

WeChat New Features & Hong Kong Police on Douyin

🟦 WeChat has been gradually rolling out a new feature that allows users to recall a batch of messages all at once, which saves you the frantic effort of deleting each message individually after realizing you sent them to the wrong group (or just regret a late-night rant). Many users are welcoming the update, along with another feature that lets you delete a contact without wiping the entire chat history. This is useful for anyone who wants to preserve evidence of what happened before cutting ties.

🟦The Hong Kong Police Force recently celebrated its two-year anniversary on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), having accumulated nearly 5 million followers during that time. To mark the occasion, they invited actor Simon Yam to record a commemorative video for their channel (@香港警察). The presence of the Hong Kong Police on the Chinese app — and the approachable, meme-friendly way they’ve chosen to engage with younger mainland audiences — is yet another signal of Hong Kong institutions’ strategic alignment with mainland China’s digital infrastructure, a shift that has been gradually taking place. The anniversary video proved popular on Douyin, attracting thousands of likes and comments.

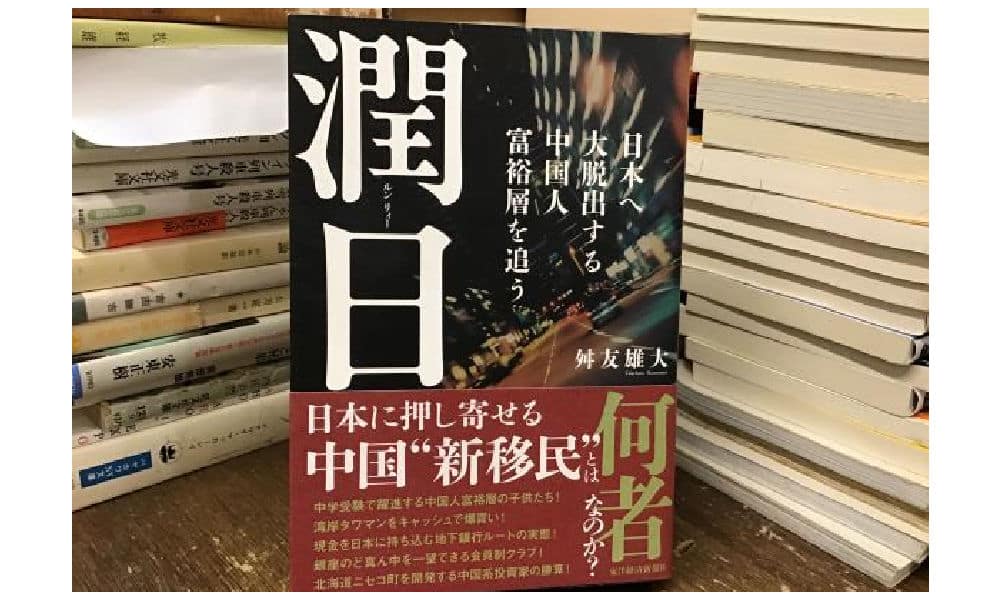

Why Chinese Elite Rùn to Japan (by ChinaTalk)

Over the past week, Japan has been trending every single day on Chinese social media in light of escalating bilateral tensions after Japanese PM Takaichi made remarks about Taiwan that China views as a direct military threat. The diplomatic freeze is triggering all kinds of trends, from rising anti-Japanese sentiment online and a ban on Japanese seafood imports to Chinese authorities warning citizens not to travel to Japan.

You’d think Chinese people would want to be anywhere but Japan right now — but the reality is far more nuanced.

In a recent feature in ChinaTalk, Jordan Schneider interviewed Japanese journalist & researcher Takehiro Masutomo (舛友雄大) who has just published a book about Japan’s new Chinese diaspora, explaining what draws Chinese dissidents, intellectuals, billionaires, and middle-class families to Tokyo.

The book is titled Run Ri: 潤日 Following the Footsteps of Elite Chinese Escaping to Japan (only available in Japanese and Traditional Chinese for now). (The word Rùn 润/潤, by the way, is Chinese online slang and meme expresses the desire to escape the country.)

A very interesting read on how Chinese communities are settling in Japan, a place they see as freer than Hong Kong and safer than the U.S., and one they’re surprisingly optimistic about — even more so than the Japanese themselves.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China Signals. For fast-moving trends and deeper dives, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you just so happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

A small housekeeping note:

This Eye on Digital China newsletter is co-published for subscribers on both Substack and the main site. If you’re registered on both platforms, you’ll receive duplicate emails — so if that bothers you, please pick your preferred platform and unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

House of Wahaha: Zong Fuli Resigns

In the year following her father’s death, Zong Fuli dealt with controversy after controversy as the head of Chinese food & beverage giant Wahaha.

Published

4 months agoon

October 14, 2025

It’s a bit like a Succession-style corporate drama 🍿.

Over the past few years, we’ve covered stories surrounding Chinese beverage giant Wahaha (娃哈哈) several times — and with good reason.

Since the passing of its much-beloved founder Zong Qinghou (宗庆后) in March 2024, the company has been caught in waves of internal turmoil.

Some context: Wahaha is regarded as a patriotic brand in China — not only because it’s the country’s equivalent of Coca-Cola or PepsiCo (they even launched their own cola in 1998 called “Future Cola” 非常可乐, with the slogan “The future will be better” 未来会更好), but also because its iconic drinks are tied to the childhood memories of millions.

Future Cola by Wahaha via Wikipedia.

There’s also the famous 2006 story when Zong Qinghou refused a buyout offer from Danone. Although the details of that deal are complex, the rejection was widely seen as Zong’s defense of a Chinese brand against foreign takeover, contributing to his status as a national business hero.

After the death of Zong, his daughter Zong Fuli, also known as Kelly Zong (宗馥莉), took over.

🔹 But Zong Fuli soon faced controversy after controversy, including revelations that Wahaha had outsourced production of some bottled water lines to cheaper contractors (link).

🔹 There was also a high-profile family inheritance dispute involving three illegitimate children of Zong Qinghou, now living in the US, who sued Zong Fuli in Hong Kong courts, claiming they were each entitled to multi-million-dollar trust funds and assets.

🔹 More legal trouble arrived when regulators and other shareholders objected to Zong Fuli using the “Wahaha” mark through subsidiaries and for new products outside officially approved channels (the company has 46% state ownership).

⚡️ The trending news of the moment is that Zong Fuli has officially resigned from all positions at Wahaha Group as chairman, legal representative, and director. She reportedly resigned on September 12, after which she started her own brand named “Wa Xiao Zong” (娃小宗). One related hashtag received over 320 million views on Weibo (#宗馥莉已经辞职#). Wahaha’s board confirmed the move on October 10, appointing Xu Simin (许思敏) as the new General Manager. Zong remains Wahaha’s second-largest shareholder.

🔹 To complicate matters further, Zong’s uncle, Zong Wei (宗伟), has now launched a rival brand — Hu Xiao Wa (沪小娃) — with product lines and distribution networks nearly identical to Wahaha’s.

As explained by Weibo blogger Tusiji (兔撕鸡大老爷), under Zong Qinghou, Wahaha relied on a family-run “feudal” system with various family-controlled factories. Zong Fuli allegedly tried to dismantle this system to centralize power, fracturing the Wahaha brand and angering both relatives and state investors.

Others also claim that Zong had already been engaged in a major “De-Wahaha-ization” (去娃哈哈化) campaign long before her resignation.

In August of this year, Zong gave an exclusive interview to Caijing (财经) magazine where she addressed leadership challenges and public controversies. In the interview, Zong spoke more about her views on running Wahaha, advocating long-term strategic growth over short-term results, and sharing her determination to not let controversy distract her from business operations. That plan seems to have failed.

While Chinese netizens are watching this family brand war unfold, many are rooting for Zong after everything she has gone through – they feel her father left her in a complicated mess after his death.

At the same time, others believe she tried to run Wahaha in a modern “Western” way and blame her for that.

For the brand image of Wahaha, the whole ordeal is a huge blow. Many people are now vowing not to buy the brand again.

As for Zong’s new brand, we’ll have to wait for the next episode in this family company drama to see how it unfolds.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment7 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West