Newsletter

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

The future is here, but it looks different than we expected. This Weibo Watch covers driverless taxis and other noteworthy, popular topics.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #33

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – The future is here

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Remarkable – A panicked mum goes to extremes

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – The passing of Cheng Peipei

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Virtual news anchors

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – Bye bye, Biden

Dear Reader,

The future is here, and it is all unfolding so much differently than we could have imagined.

Scrolling through Douyin and Weibo’s video feeds recently, there are hundreds of videos about China’s self-driving taxi revolution. The wonder and excitement over the unmanned cabs is not surprising – it is the biggest thing happening in China’s taxi industry since ride-hailing apps Didi, Kuaidi, and Uber first entered the Chinese market over a decade ago.

Luobo Kuaipao (萝卜快跑) by Baidu, called ‘Apollo Go’ in English, is the ‘robotaxi’ ride-hailing platform that is now generating the most attention online. The concept is simple: customers order the taxi via the app and enter their destination, it arrives at the meeting point, and via a panel on the side of the car, the customer inserts the last four digits of their phone number. The door then automatically opens, and they can get in the car, which will take them to where they want to go. The car is private, and the price is comparable to ride-sharing fees, but then cheaper.

There is an additional benefit: the cars are equipped with a “smart cockpit”, allowing passengers to start their journey by tapping the screen in front of them, selecting a podcast or their favorite music, controlling the air-conditioning, and watching the traffic while en route.

Currently, Luobo Kuaipao has some 500 robotaxis operating without safety drivers in Wuhan, now the world’s largest city for driverless taxis. Baidu plans to expand this fleet with an additional 1,000 robotaxis soon. Shanghai will also launch a public testing program for driverless taxi services by SAIC in the upcoming week.1

Across China, at least 16 cities are now testing self-driving vehicles, with at least 19 Chinese car manufacturers competing for global leadership. Nationwide, 20 provinces have already released policies and regulations for autonomous driving.23

In many bigger Chinese cities, smart autonomous vehicles are already part of daily life. For years now, autonomous cleaning cars have been a common sight in popular tourist spots. I remember seeing a cute little car working hard to clean the area around the Terracotta Warrior museum in Xi’an in 2019. There are also self-driving tourist shuttles, driverless trucks operating between Beijing and Tianjin, and AI-driven service carts that precisely know where crowds gather during lunch breaks, stop when people wave, and process mobile payments for hamburgers or chicken salads on the spot.

So far, so ‘futuristic.’

But it’s not all roses. Besides the many enthusiastic videos taken by Chinese riders posting their experiences of taking an unmanned, self-driving taxi for the very first time, the emergence and rising popularity of robotaxis is also leading to worries, complaints, and aggravation.

A commonly heard objection to the unmanned taxis is that they are taking away jobs in the taxi industry. Perhaps even more so than when ChatGPT first emerged, the question of AI replacing people rather than serving them is frequently popping up, with taxi drivers fearing they’ll lose their jobs as robotaxis spread throughout China. These worries can still be countered by the numbers. After all, Wuhan has more than 100,000 registered ride-hailing cars, and Luobo Kuaipao holds just around 0.40% of the market – an insignificant number. 4 But with the rise of the industry, including its competitive prices, that number is bound to change.

Another far more unexpected concern about the rise of China’s robotaxis is that they’re causing chaos in the streets by being ‘too polite.’ These autonomous taxis are trained to follow the traffic rules and act civilized in traffic – something that seems out of place in some areas, where not following the rules almost seems like a rule.

By staying in the right lane, stopping for red lights, and giving priority to other cars, pedestrians, and animals, Chinese robotaxis are causing road congestion and sometimes accidents. They often struggle with complex traffic situations; for example, a viral video showed two Luobo Kuaipao cars waiting for each other to move, holding up traffic. In Wuhan, where drivers are known for their aggressive driving style, these autonomous cars face additional challenges. They strictly follow traffic laws and are not accustomed to pushing their way into traffic, which can lead to long waits for simple turns or merges, causing delays for other drivers.

This behavior has earned them the nickname ‘Sháo Luóbo’ (勺萝卜, “silly radish”), suggesting they are sluggish, or dumb. Although Luobo Kuaipao translates to ‘Radish Runs Fast’ or ‘Carrot Run,’ implying speed and efficiency, the reality is quite different.

Also unexpected is how ‘driverless’ is not what you might have thought it is; because every car still has a “safety operator” who is remotely monitoring it from another location. One person can monitor 10 cars or even more, but they’re allegedly penalized if they close their eyes for more than three seconds.5 Videos and pictures from these robotaxi headquarters sometimes look like old-fashioned game halls or internet cafes.

Complaints about Luobo Kuaipao not being as modern as people hoped and not being as assertive as they thought ultimately boil down to a clash of cultures. Luobo Kuaipao is made in China, but it’s not programmed with the personality and ways of a Wuhan taxi driver. In the end, Wuhan drivers will need to learn from Luobo Kuaipao, and Luobo Kuaipao will need to learn from Wuhan traffic. One side will learn to become more ‘polite,’ while the other will need to add some ‘aggression’ in order to mix in with traffic.

As ‘silly’ as Luobo Kuaipao may seem now, let’s not forget that everything starts small – we all began in diapers. Nothing significant ever came without humble beginnings. The future is here, but what we consider truly ‘futuristic’ will perhaps always be a vision for the days to come.

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang have contributed to the compilation and interpretation of some topics featured in this week’s newsletter. As always, if you have any observations or ideas you’d like to share, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

References:

1 Wu Qingqing 吴青青. 2024. “The Luobo Kuaipao Versus Tesla War”[萝卜快跑,与特斯拉终有一战].” Auto Business Review (汽车商业评论), July 18 https://inabr.com/news/19693 [Accessed July 22, 2024].

2 Bradsher, Keith. 2014. “China Is Testing More Driverless Cars Than Any Other Country.” New York Times, June 14 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/business/china-driverless-cars.html [Accessed July 22, 2024].

3 Qi Xu 齐旭. 2024. “Which City is China’s First City for Autonomous Driving? [谁是中国自动驾驶“第一城”?]” China Electronics News 中国电子报, July 16 https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20240716A00W2N00?suid=&media_id= [Accessed July 22, 2024].

4 Wu Qingqing 吴青青. “The Luobo Kuaipao Versus Tesla War.”

5 Jones, Phil. 2014. “Behind Driverless Cars – The Safety Operators Who Can’t Close Their Eyes[无人驾驶车背后,是无法闭眼的安全员].” The Paper, July 19 https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_28124126 [Accessed July 22, 2024].

What’s New

“As smooth as a flying bullet” | The assassination attempt on former US President Trump at a Pennsylvania campaign event also became a major topic on Chinese social media, where Trump’s swift reaction and defiant gesture after the shooting have not only sparked discussions but also fueled the “Comrade Trump” meme machine.

Park with a view | “The ‘sea in Ditan Park’ is a perfect example of how Xiaohongshu netizens use their imagination to change the world,” a recent viral post on Weibo said. This seaview spot in the Beijing public park has become a new ‘check-in spot’ among Chinese Xiaohongshu users and influencers.

From Hollywood to Beijing | For the Dutch national broadcaster’s summer series ‘From Hollywood to Bollywood,’ I spoke about the Chinese blockbuster Battle at Lake Changjin (2021) this week. This spectacular war film depicts the story of Chinese troops during the massive Battle of the Chosin Reservoir in the Korean War, where they encircled and pushed back American forces. The film is an impressive visual spectacle, but it’s a landmark movie in other aspects as well. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, China is striving to become a global powerhouse in the film industry. At the same time, this film also helped shape new narratives of the Korean War that foster patriotism. Dutch readers can listen to or watch the entire conversation via the link. If you’re interested in learning more about this topic but not that good at understanding Dutch—nobody’s blaming you—check out this article on WoW from our archive.

What’s Trending

JULY 11

🛢️🍳 Cooking Oil Scandal | A major news topic that’s been fermenting over the past month is the revelation that some cooking oil transport trucks in China are also being used for transporting industrial oil. The issue went trending after a publication by Beijing News authored by investigative journalist Han Futao (韩福涛) on July 2, which detailed how the same tanks were used for transporting both edible oils like soybean oil and chemical oils like kerosene without any cleaning process. The food safety scandal sparked outrage online and led to people meticulously tracking the whereabouts of oil tankers and how they operate, while various tanker companies came forward to provide clarity on their procedures. The incident has raised significant awareness about the potential misuse of tankers and intensified concerns about food safety in China.

JULY 15

🚗 Trump Photo Copyrights | After the Trump rally shooting went viral across Chinese media, another trending hashtag emerged regarding the copyright of the iconic ‘raised fist photo,’ shot by award-winning photographer Evan Vucci. Chinese online sources attributed the photo’s rights to the photo agency “Visual China” (视觉中国), allegedly charging 2100 yuan ($288) per use on social media, with threats of lawsuits for unauthorized use. This sparked debates over copyright ownership, as Evan Vucci was not mentioned. In the past, the same company triggered controversy for claiming copyright for an image of the Chinese national flag. They were also sued by a Chinese photographer for claiming ownership of 173 of his photos. Visual China later clarified that they, as a partner of AP, only have distribution rights but do not own the Trump photo.

JULY 16

🌧️ Floods | Thousands of households across China have been affected by floods recently, from Sichuan to Hunan, from Henan to Shaanxi. The city of Xiangyang in Hubei is one such affected area, which experienced its strongest rainfall since the start of the flood season. Some areas nearby broke single day rainfall records, with cars in the streets being swept away by the water. In Henan, floods forced over 100,000 people to evacuate their homes, according to state media. The floods have been catastrophic, especially for farmers, leaving widespread devastation.

JULY 19

🏥 Wenzhou Doctor Killed | A vicious attack on a doctor at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University has gone viral this week, sending shockwaves across Chinese social media. The incident occurred on the afternoon of July 19, when a man suddenly attacked and stabbed Dr. Li Sheng (李晟), who was on duty in the hospital’s cardiology department. The attacker subsequently jumped off the building. Despite extensive rescue efforts, Li succumbed to his injuries that night. The incident has sparked outrage, particularly in light of several recent stabbing incidents and the ongoing issue of patient-doctor violence, leading many netizens to call for improved security measures in hospitals. Tributes to Dr. Li Sheng online describe him as a man fully dedicated to his work and patients. China’s National Health Commission condemned the attack, stating there is zero tolerance for any form of violence against medical personnel.

JULY 20

🌉 Collapsed Bridge | After heavy rain and flash floods, a highway bridge that had been in use for less than six years in Shangluo, Shaanxi Province, collapsed on July 19th, causing 25 vehicles to fall into the river. While rescue efforts were still underway, the incident has resulted in 12 known deaths and 31 missing. The past weekend, two missing vehicles were found downstream, 4 kilometers from the collapse site. More than 700 professionals from various emergency services, along with over 1,500 local officials and residents, have been mobilized for search and rescue operations.

JULY 17

🔥🚒 Shopping Mall Fire | Videos of a terrible fire at the 14-story Jiuding Department Store in Zigong, Sichuan, spread on Chinese social media on Wednesday night. Initially, the death toll stood at 8, but it later emerged that at least 16 people lost their lives in the flames despite extensive rescue efforts by firefighters. Thirty-nine people were hospitalized. The fire, now known as the “7·17 major fire accident” (“7·17重大火灾事故”), is suspected to be linked to ongoing construction work.

JULY 21

🏅🧳 Olympic Suitcase Fever | Just a few days before the start of the Olympic Games in Paris, and the Olympic fever is noticeable on Chinese social media. Chinese state media have issued phone wallpaper featuring Olympic athletes. However, what recently attracted the most attention are the suitcases used by Chinese athletes traveling to Paris. These suitcases, called “Ying Yong” (英俑), were designed exclusively for the Chinese sports delegation by a company in Hangzhou. The design is themed around the Terracotta Warriors, using red and black and featuring other details inspired by the Terracotta Army.

JULY 22

🏫 Professor Mi | A story about renowned Chinese professor Wang Guiyan (王贵元) has been blowing up on Chinese social media after he was accused of sexual misconduct by a former female doctoral student. She made these allegations through an online video against the professor, who also served as the Party Secretary and Vice Dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Renmin University of China. On July 22, the university responded to the allegations and stated that their investigations found them to be true. As a result, Wang has been expelled from the Party, his professorship has been revoked, his qualification as a graduate supervisor has been canceled, he has been removed from his teaching position at Renmin University, and his employment has been terminated.🔚

What’s Noteworthy

A mother who lost her child while shopping in a mall in Shiyan, Hubei, went to extreme measures to get her child back as soon as possible. On July 19, the panicked woman triggered the mall alarm by smashing the displays at a jewelry store with a fire extinguisher. This caused the mall to shut all its doors and prompted a police squad to arrive within minutes. A viral video of the incident showed the mother shouting for help as she broke glass displays. The child was soon located.

In the past, there have been various stories about children being kidnapped and having their appearances changed quickly, making it much more challenging to find them. One such story from 2018 showed the speed at which human traffickers work: a 5-year-old girl went missing from a local playground at 14:41, and it later became clear that the little girl, taken away in a minivan with a middle-aged woman and another child, departed her city by train just fifteen minutes later. She got off at a station some 60 miles away with changed clothes and a shaved head (read here).

Although the mother may have thought she did the right thing by smashing the displays to get help to locate her child as soon as possible, she is also receiving a lot of criticism online. Commenters argue that the woman should have never lost sight of her child in the first place, let alone vandalized mall property. The jewelry store also had nothing to do with the child going missing. The local police stated that the woman’s actions would be handled according to public security regulations, so she can expect to pay a fine and compensation to the store.

Meanwhile, there are also people who sympathize with the mother, as they don’t want to imagine what could have happened to the child if standard, slower procedures were followed. However, state media outlets warn others not to take the woman as an example.

What’s Popular

She was known as the heroine and villain of Wuxia movies, the queen of the swords, and a martial arts diva. Hong Kong actress Cheng Pei-pei (郑佩佩) trended all day on Chinese social media after news broke that she had died at the age of 78.

The Shanghai-born Cheng had a background in ballet and modern dance—skills she incorporated into the fight choreographies of the martial arts films she made for the Shaw Brothers in the 1960s and 70s. She later moved to the United States. Cheng gained international fame when she starred as Jade Fox in Ang Lee’s “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” in 2000. Cheng suffered from Corticobasal degeneration (CBD), which shares some similarities with Parkinson’s disease.

On social media, Cheng is remembered not only by other actors and celebrities but also by many regular netizens who see her passing as a major loss to the Chinese film industry. (To read more about the Shaw Brothers & Chinese cinema, check our article here.)

What’s Memorable

For this pick from the archive, and in the context of the future being here, we revisit a 2023 article about Chinese state media introducing a virtual news anchor. While the first virtual presenter was introduced in 2019, People’s Daily introduced Ren Xiaorong (任小融) as a virtual presenter/news anchor in 2023. Although virtual news presenters are not yet the norm, this is a trend that is still developing. For example, this week, China’s Military News Agency also launched their virtual anchor to improve communication efficiency.

Weibo Word of the Week

Bye Bye Biden | Our Weibo phrase of the week is Bye Bye Biden (bài bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登).

As news of Biden dropping out of the presidential race went viral on Weibo early Monday local time, it’s time to reflect on some of the popular nicknames and phrases given to US President Joe Biden on Chinese social media.

🔹 Biden in Chinese: Bàidēng 拜登

Biden in Chinese is generally written pronounced and written as Bàidēng 拜登. Although the character 拜 (bài) means “to pay respect, to worship” and 登 (dēng) means “to ascend, to climb,” they’re used here primarily for their phonetic similarity. The characters chosen are neutral to avoid any negative implications in the official translation of Biden’s name.

Why are non-Chinese names translated into Chinese at all? With English and Chinese being vastly different languages with entirely different phonetics and scripts, most Chinese people find it difficult to pronounce a foreign name written in English. Writing foreign names in Chinese not only standardizes them but also makes pronunciation and memorization easier for Chinese speakers.

🔹 Bye Biden: Bài Bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登

Because Biden is Bàidēng, and the Chinese for ‘bye bye’ is written as bài bài 拜拜, some netizens quickly created the wordplay “bài bài Bàidēng” 拜拜拜登 (“bye bye Biden”) upon hearing that Biden would not seek reelection. Try saying it out loud—it almost sounds like you’re stammering.

🔹 Old Joe: Lǎo Dēng Dēng 老登登

Another common farewell greeting to Biden seen online is “bài bài lǎo dēng dēng” 拜拜老登登, which sounds cute due to the repetition of sounds.

“Old Biden” or “lǎo dēng dēng” 老登登 is a common online nickname for Biden in Chinese. The reduplication of the 登 (dēng) makes it sound playful and affectionate, while the “old” prefix is commonly used when referring to someone older. It’s similar to calling someone “Old Joe” in English.

🔹 Biden Variations: 拜灯, 白等, 败蹬

Let’s look at some other ways Biden is nicknamed online:

Besides the official way of writing Biden with the 拜登 Bàidēng characters, there are also other variations:

拜灯: bài dēng

白等: bái děng

败蹬: bài dèng

These alternative ways of writing Biden’s name are not neutral. Although the first variation is not necessarily negative (using the formal Biden 拜 bài character but with ‘Light’ 灯 dēng instead of the other 登 ‘dēng’), the other two variations are usually used in more negative contexts.

In 白等 (bái děng), the first character 白 (bái) means “white,” which can evoke associations with old age due to white hair (白发). The character 等 (děng) means “to wait,” and the combination can imply being old and sluggish.

败蹬 (bài dèng) is typically used by netizens to reflect negative sentiments towards the American president. The characters separately mean 败 (bài): “to be defeated,” “to fail,” and 蹬 (dèng): “to step on,” “to kick.” This would never be used by official media and is also often used by netizens to circumvent censorship around a Biden-related topic.

🔹 Revive the Country Biden: Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华

Then there is 拜振华 Bài Zhènhuá: revive the country Biden

In recent years, Biden has come to be referred to with the Chinese nickname “Revive the Country Biden,” also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname has circulated online since 2020 and matches one previously given to former President Trump, namely “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国).

The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are seen as benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and dealing with China.

🔹 Sleepy King: Shuì wáng 睡王

Shuì wáng 睡王, Sleepy King, is another common nickname, similar to the English “Sleepy Joe.” During and after the 2020 American presidential elections, there were numerous discussions on Chinese social media about ‘Trump versus Biden.’ Many saw it as a contest between the ‘King of Knowing’ (懂王) and the ‘Sleepy King’ (睡王).

These nicknames were attributed to Trump, who frequently boasted about his unparalleled understanding of various matters, and Biden, who gained notoriety for being older and tired. Viral videos, some manipulated, showed him nodding off or seemingly disoriented. The name ‘Sleepy King’ then stuck.

🔹 Grandpa Biden: Bài Yéyé 拜爷爷

Throughout the years, Biden has also been nicknamed Bài yéyé 拜爷爷, “Grandpa Biden.” This is usually more affectionate, though it emphasizes his age—Trump is not much younger than Biden and is not nicknamed ‘Grandpa Trump.’

Another similar nickname is lǎo bái 老白, “Old White,” referring to Biden’s age and white hair. 白 (bái, white) can also be a surname in Chinese. This nickname makes it seem like Biden is an old, familiar friend.

On Weibo, many speculate that American Vice President Kamala Harris will be the new candidate for the Democrats, especially since she’s been endorsed by Biden. Many have little confidence that she can compete against Trump. Her Chinese name is Kǎmǎlā Hālǐsī 卡玛拉·哈里斯, commonly referred to as ‘Harris’ (Hālǐsī).

In light of the latest developments, some netizens jokingly write: “Bye bye Biden, Ha ha ha, Harris.” (Bài bài, Bàidēng. Hā hā hā, Hālǐsī 拜拜,拜登。 哈哈哈,哈里斯). With a new Democratic candidate entering the presidential race, we can expect a fresh batch of creative nicknames to join the mix on Chinese social media.

Want to read more? Also read: Why Trump has Two Different Names in Chinese.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chapter Dive

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

A look back at the three major phases of China’s social media — and why What’s on Weibo is evolving into Eye on Digital China.

Published

3 months agoon

November 12, 2025

This edition of the Eye on Digital China newsletter by Manya Koetse was sent to premium subscribers. Subscribe now to receive future issues in your inbox.

“Do you still remember going to the internet cafe, paying 2 yuan ($0.30) per hour during the day or 7 yuan ($1) for an all-nighter? Staying up playing games and surfing around?”

It’s the kind of content you’ll often see today on platforms like Douyin or Bilibili — nostalgic videos showing smoky internet cafes (wangba 网吧) from the early 2000s, where people chatted on QQ or played World of Warcraft on old Windows PCs while eating instant noodles. These clips trigger waves of nostalgia, even among internet users too young to remember that era themselves.

Internetcafe in 2005, image via 021zhaopin.com

The current nostalgia wave you see on Chinese social media is indicative of how China’s digital world has evolved over the past 25 years, shifting from one era to the next.

As I welcome a new name for this newsletter and say goodbye to ‘Weibo Watch’— and, in the longer run, to the ‘What’s on Weibo’ title, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic myself. It seems like a good moment to look back at the three major stages of Chinese social media, and at the reason I started What’s on Weibo in the first place.

1. The Blogging Boom (2002–2009): The Early Rise of Chinese Social Media

When I first came to China and became particularly interested in its online environment, it was the final phase of the early era of Chinese social media — a period that followed soon after the country had laid the foundations for its internet revolution. By 1999, the first generation of Chinese internet giants — Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Sina — had already been founded.

China’s blogging era began with the 2002 launch of the platform BlogChina.com (博客中国), followed by a wave of new platforms and online communities, among them Baidu Tieba and Renren. By around 2005, there were roughly 111 million internet users and 16 million bloggers, and the social impact was undeniable. 2005 was even dubbed China’s “year of blogging.” 1

Chinese writer Han Han (韩寒, born 1982), a high-school-dropout-turned–rally car racer, became one of the most-read figures on the Chinese internet with his sharp and witty blogs. He was just one among many who rose to fame during the blog era, becoming the voice of China’s post-1980s youth.

The rebel of China’s blog era, Han Han, became of voice of his generation.

When I moved to Beijing in 2008, I had a friend who was always out of money and practically lived in an internet cafe in the city’s Wudaokou district, not far from where I studied. We would visit him there as if it were his living room — the wangba was a local hangout for many of us.

Not only online forums and blogging sites were flourishing at the time, but there was also instant messaging through QQ (腾讯QQ), online news reading, and gaming. Platforms like the YouTube equivalents Tudou (土豆) and Youku (优酷) were launched, and soon Chinese companies began developing more successful products inspired by American digital platforms, such as Fanfou (饭否), Zuosa (做啥), Jiwai (叽歪), and Taotao (滔滔), creating an online space that was increasingly, and uniquely, Chinese.

That trajectory only accelerated after 2009, when popular Western internet services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, became inaccessible from within mainland China.

⚡ The launch of Sina Weibo in 2009 came at a crossroads for China’s social media landscape: it was not only a time when many foreign platforms exited China, but also when internet cafes faced major crackdowns.

As a foreigner, I don’t think I ever visited internet bars in Beijing anymore by that point — internet use had largely shifted to home connections. Laptop ownership was rising, and we all had (pre-smartphone) mobile phones, which we used to text each other constantly, since texting was cheaper than calling.

Some of the mobile phones in China’s 2009 top 10 lists.

Weibo came at just the right time. It filled the vacuum left by the online crackdowns across China’s internet while still benefiting from the popularity of blogging. Weibo (微博), after all, literally means “micro-blog” — micro because the number of characters was limited, just like Twitter, making short-form posts the main way of communication.

Weibo quickly became hugely successful, for many more reasons than just timing. Its impact on society was so palpable that its trending discussions often seeped into everyday conversations I had with friends in China.

In English-language media, I kept reading about what was being censored on the Chinese internet, but that wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to know — I also wanted to know what was on Weibo, so I could keep up with my social circles.

That question planted the seed for What’s on Weibo: the simple curiosity of “What are people talking about?” What TV series are popular? What jokes and controversies are everyone discussing (but that I never fully grasped)? I wanted to get a sense of an online world that was, in many ways, intangible to outsiders — including myself. As I had moved back to Europe by then, it was also a way for me to stay connected to those everyday conversations unfolding online in China.

With scissors, glue, and some paper, I started sketching out what a future website might look like.

Papercrafting the idea for a website named ‘What’s on Weibo’ in 2012.

And in March 2013, after doing my best to piece it together, I launched What’s on Weibo and began writing — about all kinds of trends, like the milk powder crisis, about China’s many unmarried “leftover men” (shengnan 剩男), and about the word of the moment, “Green Tea Bitch” (lǜchá biǎo 绿茶婊) — a term used to stereotype ambitious women who act sweet and innocent while being seen as calculating or cunning.

2. From Weibo to the Taobao Moment: China’s Mobile Social Era: (2010–2019)

Around 2014–2015, people started saying Weibo was dead. In fact, it hadn’t died at all — some of its most vibrant years were still ahead. It had simply stumbled into the mobile era, along with China’s entire social media landscape.

As mobile internet became more widespread and everyone started using WeChat (launched in 2011), new mobile-first platforms began to emerge.2 In 2012–2013, for example, apps like Toutiao and Xiaohongshu (小红书, RED) were launched as mobile community platforms. With the rapid rise of China’s new tech giants — Bytedance, Meituan, and Didi — a new mobile era was blossoming, leaving the PC-based social media world far behind.

Spending another summer in Beijing in 2014, I called it the “Taobao Moment” — Taobao being China’s most successful online marketplace, a platform for buying and selling practically everything from clothes and furniture to insurance and even Bitcoins. At the time, I thought Taobao captured everything Beijing was at that moment: a world of opportunities, quick decisions, and endless ways to earn and spend money.

On weekends, some of my friends would head to the markets near the Beijing Zoo to buy the latest dresses, purses, jeans, or shoes. They’d buy stock on Saturday, do a photo shoot on Sunday, and sell the goods online by Monday. You could often spot young people on the streets of Beijing staging their own fashion shoots for Taobao — friends posing as models, Canon cameras in hand.

During that period, What’s on Weibo gradually found its audience, as more people became curious about what was happening on Chinese social media.

Around 2016, Weibo entered another prime era as the “celebrity economy” took off and a wave of “super influencers” (超级红人) emerged on the platform. Papi Jiang stood out among them — her humorous videos on everyday social issues made her one of China’s most recognizable online personalities, helping to drive Weibo’s renewed popularity.

Witty Papi Jiang was a breath of fresh air on Weibo in 2016.

People were hooked on social media. Between 2015 and 2018, China entered the age of algorithm- & interest-driven multimedia platforms. The popularity of Kuaishou’s livestreaming and Bytedance’s Douyin signaled the start of an entirely new era.

3. The New Social Era of AI-fication and Diversification (2020–Current)

China’s social media shifts over the past 25 years go hand in hand with broader technological, social, and geopolitical changes. Although this holds true elsewhere too, it’s especially the case in China, where central leadership is deeply involved in how social media should be managed and which direction the country’s digital development should take.

Since the late 2010s, China’s focus on AI has permeated every layer of society. AI-driven recommendation systems have fundamentally changed how Chinese users consume information. Far more than Weibo, platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu have become popular for using machine-learning algorithms to tailor feeds based on user behavior.

China’s social media boom has put pressure on traditional media outlets, which are now increasingly weaving themselves into social media infrastructure to broaden their impact. This has blurred the line between social media and state media, creating a complex online media ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s not just AI and media convergence that are reshaping China’s online landscape — social relationships now dominate both information flows and influence flows. 3 Not everyone is reading the same headlines anymore; people spend more time within their own interest-based niches. It’s no longer about microblogging but about micro-communities.

China now has 1.12 billion internet users. Among new users, young people (aged 10–19) and the elderly (60+) account for 49% and nearly 21%, respectively. The country’s digital environment has never been more lively, and social media has never been more booming.

As a bit of a dinosaur in China’s social media world, Weibo still stands tall — and its trending topics still matter. But the community that was once at the heart of the Chinese internet has dispersed across other apps, where people now engage in more diverse ways than ever.

In China, I notice this shift: where I once saw the rise of Weibo, the Taobao boom, or the Douyin craze, I now see online and offline media increasingly converging. Social media shapes real-life experiences and vice versa, and AI has become integrated into nearly every part of the media ecosystem — changing how content is made, distributed, consumed, and controlled.

In this changing landscape, the mission of What’s on Weibo — to explain China’s digital culture, media, and social trends, and to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online spaces — has stayed the same. But the name no longer fits that mission.

Over the past few years, my work has naturally evolved from Weibo-focused coverage to exploring China’s digital culture through a broader lens. The analysis and trend updates will continue, but under a new name that better reflects a time when Weibo is no longer at the center of China’s social media world: Eye on Digital China.

For you as a subscriber (subscribe here), this means you can expect more newsletter-based coverage: shorter China Trend Watch editions to keep you up to date with the latest trends, along with other thematic features and ‘Chapter’ deep dives that explore the depth behind fleeting moments.

For now, the main website will remain What’s on Weibo, but it will gradually transition into Eye on Digital China. I’ll keep the full archive alive — more than twelve years of coverage that helps trace the digital patterns we’re still seeing today. After all, the story of China’s past online moments often tells us more about the future than the trends of the day.

Thank you for following along on this new journey.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 Liu, Fengshu. 2011. Urban Youth in China: Modernity, the Internet and the Self. New York: Routledge, 50.

2 Mao Lin (Michael). 2020. “中国互联网25年变迁:两次跃迁,四次浪潮,一次赌未来” [25 Years of China’s Internet: Two Leaps, Four Waves, and a Gamble on the Future]. 人人都是产品经理 (Everyone Is a Product Manager), January 3. https://www.woshipm.com/it/3282708.html.

3 Yang, Shaoli (杨绍丽). 2025. “研判2025!中国社交媒体行业发展历程、重点企业分析及未来前景展望:随着移动互联网兴起,社交媒体开始向移动端转移 [Outlook for 2025! The Development History, Key Enterprises, and Future Prospects of China’s Social Media Industry: With the Rise of Mobile Internet, Social Media Has Shifted to Mobile Platforms].” Zhiyan Consulting (智研咨询), February 7. https://www.chyxx.com/industry/1211618.html.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in the comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient — we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo.

Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. Both feature the same new content — so you can subscribe or read wherever you prefer. If you’re already subscribed on one platform and would like to move your subscription over, just let me know and I’ll help you get set up.

© 2025 Manya Koetse. All rights reserved.

China Media

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Published

11 months agoon

March 30, 2025

“This man is doing God’s work. In just six hours, he eliminated all Western media propaganda about China,” Chinese influencer Li Sanjin (李三金) said in one of his videos this week. The man he referred to, allegedly doing ‘God’s work,’ is the American YouTuber and online streamer Darren Watkins, better known as IShowSpeed or Speed, who visited China this week and livestreamed from various locations.

With 37 million followers on his YouTube account, Watkins’ visit hasn’t exactly flown under the radar. His streams from China have already accumulated over 17.5 million views on YouTube alone, and he also became the talk of the week on Chinese social media.

In China, the 20-year-old IShowSpeed is known as Jiǎkànggē (甲亢哥), or “Hyper Bro,” since the immensely popular YouTube star is known for being highly energetic.

Although IShowSpeed is originally known for soccer and gaming-related content, he’s been streaming live from various countries over the past year, from Ecuador to Bolivia, from Australia to Indonesia, from Romania to Japan, and also from the Netherlands, where a mob of fans harassed the YouTuber to such an extent that the influencer fled and panicked, until the police intervened and asked him to shut down the livestream for safety reasons — which he did not comply with.

It was not the only time IShowSpeed’s visit got chaotic. He also got into trouble during livestreams from other countries. While streaming from Norway, he injured his ankle and was swarmed by a crowd while trying to get out. In Greece and Indonesia, he had to ask for police support as well. In Thailand, he crashed a tuk-tuk into a temple wall.

In China, IShowSpeed’s livestreams went far more smoothly, and netizens, state media, and other official channels raved about his visit and its favorable portrayal of the country and its culture.

🔹 Symbol of Cultural Exchange & Positive Diplomacy

“Jiǎkànggē” became one of the viral terms of the week, on Weibo, Kuaishou, Douyin, and Toutiao. During his China trip, the livestreamer hit several YouTube milestones — not only breaking the 37 million subscriber mark while on stream, but also surpassing the magic number of 10 million views in total.

Watkins, also known for being (sometimes aggressively) loud and chaotic, suddenly emerged as a symbol of cultural exchange and positive diplomacy. The past week saw hashtags such as:

#️⃣”IShowSpeed gives young foreigners a full-window view into China” (#甲亢哥给国外年轻人开了全景天窗#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed’s Shanghai livestream breaks Western filter on China” (#甲亢哥上海直播打破西方对中国滤镜#)

#️⃣”American influencer IShowSpeed amazed by stable wifi on China’s high-speed train” (#美国网红甲亢哥被高铁稳定网络震惊#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed praised deep tried tripe for being incredibly delicious” (#甲亢哥赞爆肚太好吃了#), or

#️⃣ “IShowSpeed bridges the cultural divide” (#甲亢哥弥合文化鸿沟#).

While in Chinese media, Watkins was lauded for shining a positive light on China, this message was also promoted on English-language social media, where he was praised by the Chinese embassy in the US (#驻美大使馆称赞甲亢哥中国行#), writing:

Post by Chinese Embassy in the US on X, March 26.

“This 20-year-old American internet star is bridging cultural gaps through digital means and creating new channels for foreign audiences to better understand China.”

So what exactly did IShowSpeed do while in China?

On March 24, Watkins livestreamed from Shanghai. He wandered around the city center, visited a KFC, danced with fellow streamers, stopped by a marriage market, ate noodles, played ping-pong, had hotpot, joined a dragon dance group and got acquainted with some traditional Chinese opera performance, and walked along the Bund.

On March 26, he streamed from Beijing, starting in Donghuamen before briefly entering the Forbidden City—dressed in a Dongbei-style floral suit. He later took a stroll around Nanluoguxiang and the scenic Houhai lake, rode a train, and finally visited the Great Wall, where he did backflips.

In his stream on March 28, Watkins traveled to Henan to visit the famous Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng, hoping to find a master to teach him kung fu. He trained with Shaolin monks—footage that quickly went viral.

Lastly, on March 29, he opened his own Weibo account and published his first post. On Douyin, he shared a video of his visit to Fuxi Mountain in Zhengzhou, featuring the popular “Stairway to Heaven” tourist spot.

On social media, many viewers were captivated by the content. One major talking point was the remarkably strong internet connection that allowed him to livestream for six-hour stretches without losing signal in Shanghai. (Though his Beijing stream started off patchier, the drop was minor.) For many, it symbolized the quality of China’s 5G services.

Foreign viewers also praised how safe, friendly, and clean the country appeared, and how his streams highlighted various aspects of Chinese culture—from everyday people to traditional arts and local cuisine.

🔹 Telling & Spreading China’s Stories Well

It is no wonder the success of the Jiǎkànggē livestreams is celebrated by Chinese official media in an age where China’s foreign communication aims to increase China’s international discourse power, shaping how the world views China and making that image more credible, more respectable, and more lovable.

That’s not just an observation — it’s an official strategy. Introduced by Xi Jinping in 2013, “Telling China’s Story Well” (“讲好中国故事”) is a political slogan that has become a key propaganda strategy for China and continues to be a priority in finding different ways of promoting Chinese culture — new ways of telling China’s story in the social media age – while countering Western dominant narratives about China.

In increasingly digitalized times, it is not just about telling China’s story well, but also spreading China’s message effectively — preferably through genuine and engaging stories (Cai 2013; Qiushi 2021).

Especially young, non-official ‘storytellers’ can make China’s image more relatable and dynamic. One major example, highlighted in a 2022 case study by Zeng Dan (曾丹), is Chinese influencer Li Ziqi (李子柒). You’ve probably heard of her, or seen snippets of her videos: she creates soothing, cinematic content depicting China’s countryside lifestyle, focused on cooking, crafts, and gardening. With 26 million followers on YouTube, Li Ziqi became a viral sensation who successfully communicated an authentic and appealing ‘China story’ to a broad global audience.

Li Ziqi in one of her YouTube videos.

Although the calm and composed Li Ziqi and the loud, chaotic IShowSpeed couldn’t be more different, they have some things in common: both have large international fanbases, including their millions of YouTube subscribers; they offer perspectives that differ from Chinese state media or official channels; and they have the capacity not just to tell China’s story well, but to spread it effectively through videos and livestreams.

🔹 Spontaneous Stream or Scripted Propaganda?

IShowSpeed’s China streams have triggered a wave of responses from fans and viewers, sparking discussions across international social media and even making newspaper headlines.

In English-language online media spheres, there appear to be a range of perspectives on Watkins’ China trip:

📌 One prominent view—also echoed by various foreign influencers on YouTube and other platforms—is that IShowSpeed’s visit counters “Western media lies” about China and has successfully shown the “real China” through his livestreams. The Shanghai-based media outlet Radii claimed that “IShowSpeed’s China Tour is doing more for Chinese Soft Power than most diplomats ever could.”

📌 Others challenge this narrative, questioning which dominant Western portrayals of China IShowSpeed has actually disproven. Some argue that the idea of China being a “bleak place with nothing to do where people live in misery” is itself a false narrative, and that presenting IShowSpeed’s livestreams as a counter to that is its own form of propaganda (see: Chopsticks and Trains).

📌 There are also those who see Watkins’ trip as a form of scripted propaganda. To what extent were his livestreams planned or orchestrated? That question has become one of the central points of debate surrounding the hype around his visit.

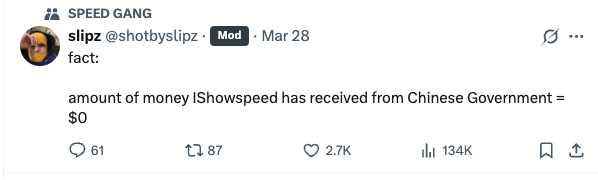

These rumors have been addressed by cameraman Slipz (@shotbyslipz), who took to X on March 28, 2025. Slipz posted that the team is “(..) not making political content, not any documentary and no journalism,” and later added: “Fact: amount of money IShowSpeed has received from Chinese Government = $0.”

But does the fact that IShowSpeed did not receive money from the Chinese government mean that it wasn’t also a form of China promotion?

➡️ Organized — it definitely was. Any media trip in China has to be. IShowSpeed would have needed a visa, he had translators with him, and throughout the streams it’s evident that local guards and public security officers were present, walking alongside and helping to keep things under control, especially in crowded areas and at major tourist spots — from Nanjing Road in Shanghai to an entire group of guards seemingly accompanying the entourage in the Forbidden City.

One logistical “advantage” to his visit was the fact that YouTube is blocked in China. While some Chinese fans do bypass the Great Firewall to access the platform, IShowSpeed remains far less known in China than in many other countries — a factor that likely contributed to how smoothly the streams went and helped prevent chaos. The team also launched a Douyin account during the trip, where he now has over two million followers. (To stream directly to their 37 million followers on YouTube, Watkins’ team either needed a VPN to access WiFi or had arranged roaming SIM cards to stay connected.)

➡️ Was it staged? Many parts clearly weren’t: casual public conversations, spontaneous barber visits in both Shanghai and Beijing (with barbers looking unsure of how to handle the situation), and wholesome fan encounters. There was even a moment when Watkins walked into a public restroom and forgot to mute the sound.

But other parts of the trip were undeniably staged — or at least framed to appear spontaneous. When visiting a marriage market in Shanghai, for instance, two actors appeared, including one woman with a sign stating she was looking for someone “capable of doing backflips.”

When Watkins took a “random” ride in what was described as the fastest car in China — the Xiaomi SU7 Ultra — the vehicle appeared to be conveniently parked and ready.

Similarly, when the streamer “ran into” Chinese-American TikTok influencer Miles Moretti (李美越) in Beijing, it turned out to be the person who would give him the now-iconic bright Dongbei flower suit and accompany him on his journey.

The ping-pong, the kung fu, the Peking opera, the hotpot, the Forbidden City tour — it all plays into the kinds of experiences that official channels also like to highlight. While likely planned by Watkins’ team in coordination with local partners, it was all far more orderly and tourism-focused than, for example, Watkins’ chaotic visit to the Netherlands.

Watkins and his entourage were also well-informed about the local dos and don’ts. At one point, Watkins even mentions “following the rules,” and when Moretti tells him mid-stream that “somebody very important lives on our left,” Watkins asks “Who?” — but the camera zooms out and the question goes unanswered, suggesting they may have been reminded that certain names or topics were off-limits (judge the moment for yourself here).

The livestream didn’t always go exactly the way Watkins wanted, either. When he attempted to take more random walks around the city, the crew appeared to be informed that some areas were off-limits, and he was asked to return to the car to continue the trip (clips here and here).

🔹 The “Nàge” Song

One major talking point surrounding IShowSpeed’s China livestreams was “the N-word.” No, not that N-word — but the Chinese filler word “nàge” or “nèige” (那个). Like “uhm” in English or “eto” in Japanese, “nàge” is a hesitation marker commonly used in everyday Mandarin conversation. It also functions as a demonstrative pronoun meaning “that.”

The word has previously stirred controversy because of its phonetic resemblance to a racial slur in English. In 2020, an American professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business was even temporarily suspended after using the word during an online communications class — some students misunderstood its context and took offense.

The word — and the song “Sunshine, Rainbow, White Pony” (阳光彩虹小白马) by Chinese singer Wowkie Zhang (大张伟), which repeatedly features the word nàge in its chorus — popped up multiple times during Watkins’ trip. The catchy tune essentially became the theme song of his visit.

The first nàge moment actually already appeared within the first five minutes of Watkins’ Shanghai stream, when a Chinese comedian approached him on the street, trying to recall a joke. “What?!” Watkins reacted, with laughter in the background. “That’s not a joke, you said n**! It’s my first five minutes in China!” he exclaimed, before patting the man’s back in a friendly gesture, clearly not offended.

🔄 It resurfaced again within the first hour when Watkins visited a marriage market and one of the performers sang the Wowkie Zhang song. Watkins initially acted shocked, then demanded they sing it again — only to burst out laughing and start singing along.

🔄 Later, he sang the song again with a street saxophonist and encouraged others to join in.

🔄 At other moments, he played up the drama again, feigning anger when a crowd broke into the chorus, and it became a recurring gag throughout the streams.

These incidents all seem staged. One of the main reasons Watkins is known to many netizens in China is because of an older video clip showing his exaggerated reaction to the nàge song — dating back to at least 2022. So while it may have looked spontaneous, Watkins was already familiar with the word and the viral song long before his China trip.The attention given to the nàge ‘controversy’ was likely amplified for views and engagement.

While Watkins was clearly in on this part of the show — as with others — he also seemed genuinely, and at times amusingly, unaware of many things in China. He repeatedly referred to RMB as “dollars,” mistook elderly women for retired YouTube streamers, and even assumed that a woman livestreaming near the Forbidden City was reading his chat and trying to collaborate with him — although she seemed totally uninterested and was just minding her own business.

🔹 A Win-Win Situation

In the end, IShowSpeed’s visit highlighted two sides effectively doing their job. Watkins and his team successfully arranged a YouTube trip that generated high ad revenue, attracted millions of new subscribers, and boosted his brand and global fame.

On the Chinese side, there was clearly coordination behind the scenes to ensure the trip went smoothly: avoiding controversy, ensuring safety, and showcasing positive aspects of Chinese culture. From traditional opera and kung fu to ping pong, IShowSpeed’s content gave center stage to the kinds of cultural highlights that align closely with China’s official narratives and tourism goals. Even if the government didn’t pay the YouTuber directly, as his team has emphasized (and there’s no reason to doubt them), the trip still fit seamlessly into China’s soft power strategy.

IShowSpeed’s China visit has created a unique media moment that resonates for several reasons: it’s the encounter of a young modern American with old traditional China; it is a streamer known for chaos visiting a nation known for control. And it brings different benefits to both sides: clicks and ad revenue for IShowSpeed, and free foreign-facing publicity for China.

No, IShowSpeed didn’t undo years of critical Western media coverage on China. But what his visit shows is that we’ve entered a phase where China is becoming more skilled at letting others help tell its story — in ways that resonate with a global, young, online audience. He didn’t do “God’s work.” He simply did what he always does: stream. And with China’s help, he streamed China very well.

There’s so much more I want to share with you this week — from Chinese reactions to the devastating Myanmar earthquake, to a recent podcast I joined with Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf (link in Dutch, for those interested). But it also happens to be my birthday today, and I’m really hoping to still grab some birthday hotpot — so I’ll wrap this up here. I’ll keep you informed on the other trends in the next newsletter.📨.

Best,

Manya

(@manyapan)

References:

Cai, Mingzhao 蔡名照. 2013. “Telling China’s Stories Well and Spreading China’s Voice: Thoroughly Studying and Implementing the Spirit of Comrade Xi Jinping’s Important Speech at the National Conference on Propaganda and Ideological Work [讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音——深入学习贯彻习近平同志在全国宣传思想工作会议上的重要讲话精神].” People’s Daily 人民日报, October 10. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1010/c1001-23144775.html. Accessed March 29.

Qiushi 求是网. 2021. “Xi Jinping: Telling China’s Story Well, Spread China’s Voice Well [习近平:讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音].” Qs Theory, June 6. http://www.qstheory.cn/zhuanqu/2021-06/02/c_1127522386.htm. Accessed March 29.

Zeng Dan 曾丹. 2022. “How to Tell China’s Story Well: Taking Li Ziqi as an Example [如何讲好中国故事——以李子柒为例].” Progress in Social Sciences 社会科学进展 4 (1): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.35534/pss.0401002.

What’s Featured

Quite terrifying and interesting, as this trending story touched upon so many different issues.

What started as a single snarky comment on Weibo spiraled into an online witch hunt, exposing not just some dark sides of online Kpop fandom but also, most importantly, the vulnerabilities in China’s digital privacy.

Read the story, the latest by Ruixin Zhang 👀

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West