China Food & Drinks

Dinner in Pyongyang – North Korea’s Government-Run Restaurant in Beijing

Pyongyang is a restaurant chain owned and operated by the North Korean government. Pyongyang Restaurants, all staff from the DPRK’s capital, offer a glimpse inside the world’s most secretive nation.

Published

10 years agoon

Pyongyang is a restaurant chain owned and operated by the North Korean government. The restaurants, all staff from the DPRK’s capital, offer a glimpse inside the world’s most secretive nation. What’s on Weibo went for a North Korean bite in the Beijing branch.

Three waitresses greet us with a short and stern smile when we walk into Beijing’s Pyongyang Restaurant (平壤馆). They all have pretty faces, and their clothes and make-up look impeccable. When we are seated and receive the menu, my friend asks our waitress in Korean: “Where are you from?” “Pyongyang,” she says (we could have guessed), and her smile is gone. She leaves the table before we can ask another question.

North Korea is one of the most secretive states in the world. The country made international headlines this week when its government announced it had succeeded in testing a hydrogen bomb. Even to China, North Korea’s closest economic and diplomatic ally, the country remains unpredictable, and many Chinese seem to find the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) an intriguing subject; ‘North Korea’ (朝鲜) has become a daily recurring topic on Chinese social media.

Since the 1990s, the North Korean government has opened Pyongyang Restaurants in several countries across Asia. Except for the restaurants in China near to the North Korean border and elsewhere (Beijing, Shanghai, Harbin, etc), there are also branches in Jakarta, Vientiane, Phnom Penh, Kuala Lumpur, and other cities. The branch in Cambodia’s Siem Reap is one of the oldest and biggest in Southeast Asia, and is very popular amongst locals and tourists. In 2012, a Dutch branch was opened in Amsterdam, but it was permanently closed in 2014.

An additional reason why restaurants are an interesting business venture for the DPRK leadership, Duncan writes, is that they offer a chance “to spy on South Korean business people and gain knowledge from them when they are drunk” (2014, 77). This claim is confirmed by the

Korea Joongang Daily, that reports how waitresses eavesdrop on their guests’ conversations to gather information on public opinion. They are ordered to keep the North Korean authorities posted on a daily basis. According to sources, there are surveillance cameras and wiretapping devices installed in some establishments.

In a way, Pyongyang Restaurants are extensions of the North Korean state, and are controlled just as strictly. Much has been written about the mysterious lives of the restaurant’s staff (see Xinhua, BBC, The Atlantic, The Guardian, etc.) Waitresses are carefully selected based on their (privileged) family background, looks and height.

Living in cosmopolitan cities does not bring North Korean waitresses a modern lifestyle; they do not have a phone, nor internet, and live highly regimented lives. They often live above or near the restaurant, and are not allowed to freely roam around the city. They are sent back to their homeland once their period of work abroad is finished. If they escape, their families in North Korea face punishment, DPRK expert Marcus Noland says.

“I drove two friends back to Beijing yesterday. When we got there it was already noon, and we decided to go to Beijing’s famous North Korean Pyongyang Restaurant,” one netizen writes: “The restaurant food is okay, better than most Korean places. The waitresses all come from North Korea, and apart from us, nobody seemed to speak Chinese. Although the waitresses were helpful, there was certainly some distance.”

“From the ink paintings on the wall, via the North Korean songs on their television, to the pretty North Korean waitresses; it all creates such a strange atmosphere”, another Weibo netizen writes.

We experience that same strange atmosphere upon our visit to Pyongyang Restaurant. The dining hall is brightly lit with fancy chandeliers, but the rest of the restaurant’s decor is surprisingly plain and grey. The North Korean landscape paintings on the wall give an extra Pyongyang feel to the restaurant. The television in the corner of the room shows a music programme on Korean Central Television.

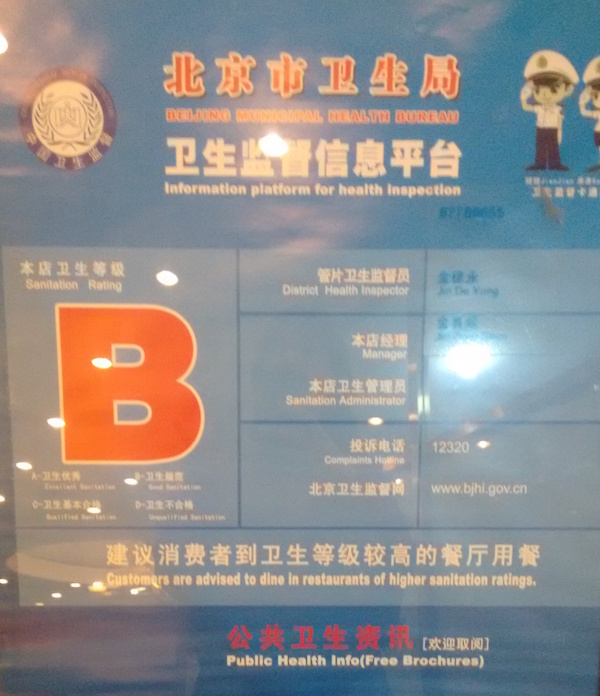

According to the outside sign of the Chinese health inspection, this restaurant is a ‘B’ – which means that it is advised to “dine in restaurants of higher sanitation ratings”. Although the restaurant looks fairly clean, its only toilet looks less immaculate.

It is a Sunday night, and only about 6 of the restaurant’s 16 tables are occupied. The restaurant’s guests are mostly South Korean and Chinese.

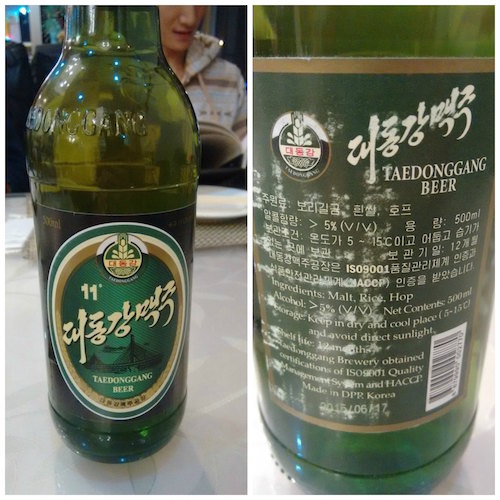

The menu offers a selection of different dishes, ranging from 20 RMB (3 US$) cold noodles, to 1080 RMB (164 US$) seafood soup. There are several fish dishes priced around 100 RMB (15 US$), or whole chickens of 198 RMB (30 US$). We start off with a cold made-in-DPKR Taedonggang beer, which tastes fresh and hoppy.

The waitresses do speak some Chinese, but with our broken Korean, we succeed in ordering some traditional dishes, such as Kimchi, mixed rice dish Bibimbap, blood sausage (a stew of Sundae), and a tofu soup (Sundubu jjigae).

After the performances, the staff’s uniforms and serious faces return, and the waitresses go back to their routine duties – clearing the tables and bringing the bill. The fake rose that they brought to our table during one of their performances is taken back; we are not allowed to keep it.

On Weibo, people seem amazed with the fact that all staff is from North Korea. Other aspects of the restaurant also surprises them: “I went to Pyongyang Restaurant with my friend the other day,” one netizen writes: “And as usual, I turn on my phone to connect to the wifi. To my surprise, I found none. ‘Why is there no wifi?’ I mumbled. ‘Because you’re in Pyongyang,’ my friend said.”

We are happy to step outside into the smoggy streets after dinner. It is interesting to be in Pyongyang for one night, but we prefer to be in Beijing.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Pyongyang Restaurant

78 Maizidian St, Chaoyang, Beijing

朝阳区麦子店街华康宾馆1层

References

Duncan, Simon. 2014. “North Korean Government-operated restaurants in Southeast Asia.” Second International Conference on Asian Studies, 75-77. Sri Lanka: International Center for Research and Development.

Images: Except for the two images of the waitresses at work (Weibo, BBC) all pictures are the author’s own.

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

[showad block=1]

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Animals

China Faces Unprecedented Donkey Shortage Crisis

“We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

Published

2 months agoon

October 5, 2025

China is facing a serious donkey shortage. China’s donkey population is far below market demand, and the prices of donkey-related products continue to rise.

Recently, this issue went trending on Weibo under hashtags such as “China Currently Faces a Donkey Crisis” (#我国正面临缺驴危机#).

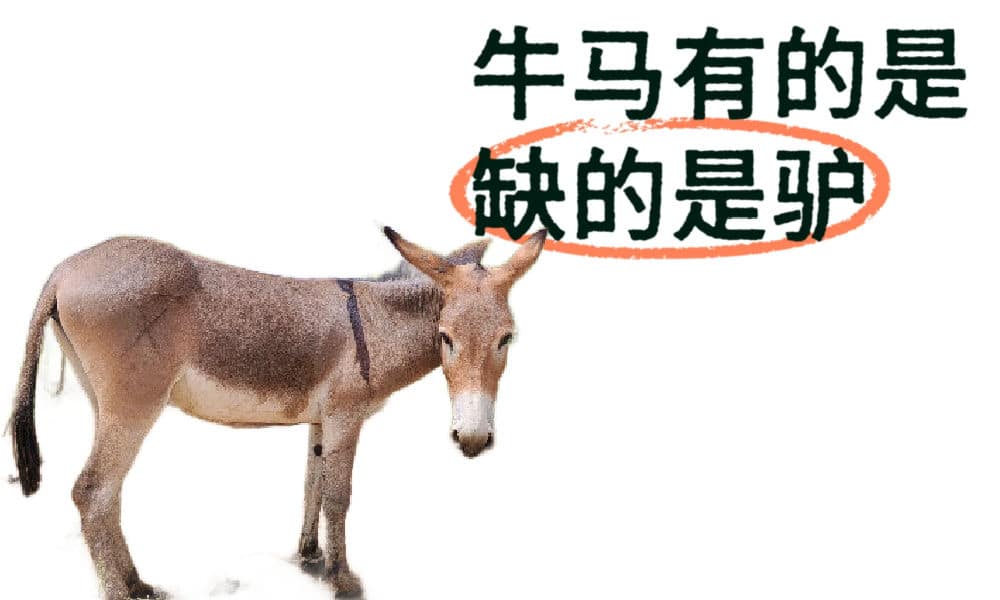

The Donkey Branch of China’s Livestock Association (中国畜牧业协会驴业分会) addressed this issue in Chinese media earlier last week, telling China News Weekly (中国新闻周刊): “We have plenty of cattle and horses in China now — just not enough donkeys” (“目前我国牛马都不缺,就缺驴”).

China’s donkey population has plummeted by nearly 90% over the past decades, from 11.2 million in 1990 to just 1.46 million in 2023.

The massive drop is related to the modernization of China’s agricultural industry, in which the traditional role of donkeys as farming helpers — “tractors” — has diminished. As agricultural machines took over, donkeys lost their role in Chinese villages and were “laid off.”

Donkeys also reproduce slowly, and breeding them is less profitable than pigs or sheep, partly due to their small body size.

Since 2008, Africa has surpassed Asia as the world’s largest donkey-producing region. Over the years, China has increasingly relied on imports to meet its demand for donkey products, with only about 20–30% of the donkey meat on the market coming from domestic sources.

China’s demand for donkeys mostly consists of meat and hides. As for the meat — donkey meat is both popular and culturally relevant in China, especially in northern provinces, where you’ll find many donkey meat dishes, from burgers to soups to donkey meat hotpot (驴肉火锅).

However, the main driver of donkey demand is the need for hides used to produce Ejiao (阿胶) — a traditional Chinese medicine made by stewing and concentrating donkey skin. Demand for Ejiao has surged in recent years, fueling a booming industry.

China’s dwindling donkey population has contributed to widespread overhunting and illegal killings across Africa. In response, the African Union imposed a 15-year ban on donkey skin exports in February 2023 to protect the continent’s remaining donkey population.

As a result of China’s ongoing “donkey crisis,” you’ll see increased prices for donkey hides and Ejiao products, and oh, those “donkey meat burgers” you order in China might actually be horse meat nowadays. Many vendors have switched — some secretly so (although that is officially illegal).

Efforts are underway to reverse the trend, including breeding incentives in Gansu and large-scale farms in Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang.

China is also cooperating with Pakistan, one of the world’s top donkey-producing nations, and will invest $37 million in donkey breeding.

However, experts say the shortage is unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

The quote that was featured by China News Weekly — “We have cows and horses, but no donkeys” (“牛马有的是,就缺驴”) — has sparked viral discussion online, not just because of the actual crisis but also due to some wordplay in Chinese, with “cows and horses” (“牛马”) often referring to hardworking, obedient workers, while “donkey” (“驴”) is used to describe more stubborn and less willing-to-comply individuals.

Not only is this quote making the shortage a metaphor for modern workplace dynamics in China, it also reflects on the state media editor who dared to feature this as the main header for the article. One Weibo user wrote: “It’s easy to be a cow or a horse. But being a donkey takes courage.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Food & Drinks

China’s Prefab Storm Explained: Luo Yonghao vs. Xibei & the Great Yùzhìcài Debate

A big debate over yùzhìcài — pre-made food — has boiled over on Chinese social media after a Xibei food review by Luo Yonghao pushed the issue into the spotlight.

Published

2 months agoon

September 20, 2025It started with a negative restaurant review on social media, triggered a nationwide discussion about pre-made food in restaurants, and ended with far-reaching consequences. The Xibei controversy, explained.

A major discussion that first broke out on Chinese social media two years ago is being picked up again this month – and it’s completely blown up.

It is all about “yùzhìcài” (预制菜), ‘pre-fabricated meals’ or ‘pre-made food.’

From School Cafeterias to Restaurants

Back in 2023, there was widespread discussion over prefab meals when the new school season started and parents discovered that their children’s school cafeterias had transitioned from freshly prepared meals to ready-made ones.

Although the shift to “yùzhìcài” is part of a broader trend in China that has gained more attention over recent years, there has also been significant resistance to this change due to concerns over the meals lacking nutrition, containing too many additives, and not being safe enough. These issues become especially relevant when it’s about the meals being served to kids, and many people called for more legislation on the issue.

Now, in 2025, the resurfaced prefab food discussion is more focused on the restaurant industry than campus cafeteria.

This ‘prefab storm’ started when well-known entrepreneur and influencer Luo Yonghao (罗永浩) went out for dinner on September 10 with some friends at Xibei (西贝), a major Chinese restaurant chain specializing in northwestern Chinese cuisine.

Example of Xibei dishes (not by Luo, but by a Xiaohongshu user).

On his Weibo account (@罗永浩的十字路口), he wrote about the disappointing experience:

His post immediately set off a nationwide storm of discussions.

What Is Yùzhìcài?

A large party of the online discussion was about what exactly counts as yùzhìcài.

After all, the entire process of making tofu, for example, from soybean to final product, is a form of pre-processing that’s been part of Chinese cuisine for centuries.

According to China’s State Administration for Market Regulation, the term “yùzhìcài” applies to food that’s been prepped in advance using large-scale methods such as marinating, stir-frying, steaming, and then packaged for transport and sale to consumers or use in restaurant service. They’re not ready to eat as-is and must be heated or cooked before serving.

Examples of yuzhicai, pre-made food.

Still, many netizens wonder: does using a central kitchen qualify as yùzhìcài? Do frozen ingredients or factory-processed foods fall into the same category?

Many people aren’t necessarily opposed to pre-made dishes — some even associate them with better hygiene, especially when produced in regulated facilities, compared to meals prepared in smaller restaurant kitchens. At the same time, however, many object to pre-made food, assuming it is less healthy, or even unhealthy.

The “Pre-made War”

Luo’s criticism also wasn’t mainly about pre-made food in general, but about the high price and lack of disclosure about what’s being served.

Like one comment said: “I don’t mind pre-made food, but I do mind when the price doesn’t match.”

What made Luo’s comments particularly explosive was his choice of words — calling it “truly disgusting.”

When Chinese media contacted Xibei for comment, a spokesperson denied their food was pre-made and stressed that stir-fried dishes are cooked on-site, noodles are hand-kneaded, and beef marrow bones are freshly boiled each morning (#西贝回应被吐槽是预制菜#).

In response, Luo jokingly wrote: “…and their plastic bags are freshly cut, the microwave freshly opened, their prepared scripts freshly read…”

Xibei chairman Jia Guolong (贾国龙) clearly was not amused.

Xibei’s founder, Jia Guolong, was emotional about the controversy, which deeply affected the Xibei brand.

On September 11, he made a statement, saying:

Jia not only announced plans to sue Luo Yonghao, he even promised to launch a special “Luo Yonghao Menu” (罗永浩菜单) in Xibei restaurants.

Again, Luo responded:

But he didn’t leave it at that — the “pre-made war” was on. Luo even offered a RMB 100,000 ($14,000) reward for proof that Xibei uses pre-made food (an offer he later admitted was “impulsive”).

He also livestreamed, highlighting how Xibei’s children’s meals used frozen broccoli with a shelf life of up to two years, questioning whether such ingredients can be considered fresh, and criticizing the practice of selling “pre-made” vegetables at fresh food prices.

Luo’s livestream.

He further showed images of packaged sea bass used in Xibei kitchens, noting that the ingredients list included food additives sodium tripolyphosphate and sodium hexametaphosphate, and that the fish had a shelf life of up to 18 months.

Xibei Apologizes

Xibei, meanwhile, experienced what they called the largest external crisis since the founding of their company, with daily revenues dropping dramatically.

Trying to win back consumer trust, Xibei announced that all stores nationwide would open their kitchens to customer visits, actually launched their “Luo Yonghao Menu,” and made a promise: “If it doesn’t taste good, you don’t pay.”

But so far, Xibei hasn’t been able to fully win back the public’s favor. After all, it turns out that Xibei does use a central kitchen where food is prepared (meat is cut, vegetables washed), but because Chinese regulations do not count central kitchens making semi-finished or finished dishes for their own restaurants as yùzhìcài, many feel Jia Guolong is making use of a loophole.

Most people don’t care about the legal definition of yùzhìcài. What they care about is that the food is free of additives, fairly priced, tasty, and above all — fresh. Some argue that central kitchens and factories that make prefab food follow almost identical processes in essence.

In hopes of calming the PR crisis, Xibei also issued a public apology on September 15 in which they expressed regret for not meeting customer expectations and announced some changes to their company, including ensuring that more meals — including children’s meals — would be fully made in-store.

The Xibei Controversy: Consequences & Takeaways

The heated confrontation between Luo and Xibei has far-reaching consequences.

▪️ Legal Consequences

One of those consequences is a legal one. Although already underway, the public attention on prefab food might have quickened the process of regulation.

On September 13, the National Health Commission announced a draft law of the National Food Safety Standard for Pre-Made Dishes (预制菜食品安全国家标准). Once finalized, China will have a unified definition of “prefab food,” and for the first time, restaurants will be required to disclose whether and how they use it.

Luo Yonghao applauded the move, and while cheering for the upcoming regulations, he also said that the Xibei matter could be put to rest for now — after all, he suggested that legal clarity was one of his main goals.

▪️ Industry-Wide Impact

Seeing the dramatic impact this controversy has had on Xibei, other Chinese restaurant brands have begun to anticipate the yùzhìcài issue.

The Green Tea Restaurant quietly removed its signs saying all of its food is freshly made.

The Chinese dining chain Green Tea Restaurant (绿茶餐厅), for example, apparently wanted to avoid a PR crisis of its own and quietly removed its storefront sign that read: “No pre-made food, all dishes freshly made.” On their delivery packaging, they also blacked out the “no pre-made food” sentence, according to some media.

Livestreaming from the kitchen as a way to build consumer trust.

The controversy is also being used to the advantage of some restaurants, which have now begun live broadcasting their kitchens to show dishes being prepared in real time (后厨现炒, 后厨直播) — something that many Chinese restaurants, like Haidilao (海底捞), already did previously, and which is now being promoted as another way to build consumer trust.

▪️ A Win for Consumers

For consumers, the controversy has brought much more awareness about food preparation processes, with more people demanding transparency about the food they are served.

“Prefab Food Transparency” (预制菜透明化) has become a buzzword of the week, along with “Freshly Cooked, Freshly Stir-Fried” (现制现炒) as a way to win over diners.

Notably, there is one Chinese restaurant chain that is not being scrutinized this week.

Saizeriya (萨莉亚), a popular Japanese chain selling “Italian” food, is known as the “king of pre-made food.”

The reason Saizeriya has avoided public backlash despite being known for its yùzhìcài is because it is very affordable, and it has never pretended to be a “freshly made” restaurant — what you see is what you get.

That transparency, in the end, is what consumers are looking for — preferring consistency, honesty, and affordability over a more high-end restaurant like Xibei that presents itself as fresh while secretly using frozen ingredients.

In the end, that’s perhaps the lesson that can be learned from this whole ordeal for other restaurant chains: don’t pretend to be freshly made if you’re not, don’t be vague about your use of yùzhìcài, don’t mess with children’s food, and remember that in China’s dining culture and online environment, consumer trust is hard-won, and easily lost.

By Manya Koetse

Thanks to Miranda Barnes

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral5 months ago

China Memes & Viral5 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

Olivier bourgault

August 8, 2016 at 6:45 pm

Um… your wrong. Please fact check before you write some more bs. There’s no such thing as north korean restaurants in south Korea. Why would north korean government send their citizens their when many defect and seek refuge in this country. Plus what the hell is south Korea thinking if they let pyongyang restaurants do business in their country. Makes no sense. Thirdly if you can’t find a better korean restaurant than that in Beijing you suck.

Manya Koetse

August 8, 2016 at 7:24 pm

Dear Olivier, thank you for your comment. We always fact-check and refer to our sources. You are not right in saying that there are no North Korean restaurants in South Korea (http://smileyjkl.blogspot.nl/2012/11/north-korean-restaurant-in-seoul.html – you might want to fact-check before writing 😉 ). You are, however, right in pointing out that they are probably not the same as that in Beijing and other cities. Thanks for this – we’ve adjusted it. Thirdly, nowhere did we write that there were no better Korean restaurants in Beijing than this particular one. You might want to check out other blogs if you were looking for restaurants recommendations. Regards, Manya (What’s on Weibo editor)

Olivier bourgault

August 9, 2016 at 5:42 am

Oops. I meant no such thing as state owned pyongyang restaurants in south Korea. 🙂 😛