Dear Reader

Waiting for Karma in the Maskpark Scandal

From Telegram to Shaolin Temple, the two scandals that rocked Chinese social media this week.

Published

5 months agoon

🔥 This column also appeared in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Earlier this month, a female Weibo user nicknamed “The Armpit-Haired Dude” (@腋毛大汉) posted an exposé on Weibo, revealing the existence of a large-scale anonymous Chinese-language sex exploitation and voyeuristic content community on the encrypted messaging app Telegram.

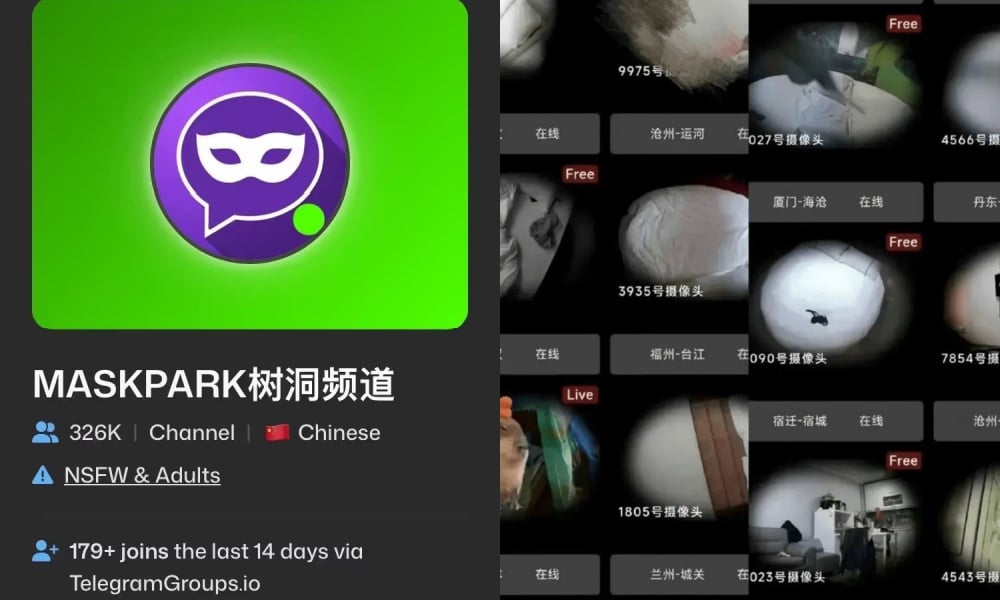

In this Telegram network, called “Maskpark Treehole Forum” (面具公园树洞论坛), participants shared hidden camera footage, non-consensual intimate videos, and fetishised depictions of thousands of women. (The word “treehole” or “tree hollow” 树洞 refers to a place of anonymous confessions.)

News of the community spread across social media like wildfire and set off a storm of outrage, as it soon became clear that what was happening within this network was deeply disturbing, and that the scale of the activities was enormous.

“Maskpark” had over 100,000 active members—mostly Chinese men—and dozens of sub-channels, each with tens of thousands of members sharing images and footage, impacting countless victims.

There were all kinds of victims whose images and videos were shared in these groups in dozens of ways.

Some girls were recorded with hidden pinhole cameras in public bathrooms; some women’s videos were taken through private home surveillance; some females were unknowingly recorded in hotels or even hospitals; some were simply taking the subway when unknowingly filmed up their skirts; some material was taken from private social media accounts.

Some of the women were the sharers’ own sisters, mothers, girlfriends, wives, colleagues, or even daughters—exposed to thousands of online strangers for sexual gratification.

The group even had a specific term for this practice of sharing women’s images and videos: “offering tributes” (shàng gòng, 上供).

Soon, netizens linked ‘Maskpark’ to a man named Mai Zihao (麦梓豪), known online as @麦Mako, who had previously operated a dating app also called Maskpark. On that platform, men had to be invited and pay to meet women online. The app ran for two years before it was taken offline in 2020 as an illegal mobile application. Among other issues, the platform routinely turned a blind eye to sex work and explicit transactions taking place on its network.

In response to the online accusations, Mai initially issued a brief statement denying any involvement with the Maskpark Telegram community, but then proceeded to wipe all his social media accounts across every platform, which only further fueled suspicions.

Meanwhile, the Maskpark Telegram group was switched to private, and is now no longer searchable on the app.

On Chinese social media, frustration has continued to grow as days — now weeks — have passed without a single word from Chinese authorities. So far, there have been no reports of any official investigations into the key individuals involved in the Telegram group.

Telegram, which was founded by Russian tech entrepreneurs Pavel and Nikolai Durov in 2013, is officially blocked in mainland China. The app company is headquartered in Dubai.

“It’s not China’s Nth Room”

The ‘Maskpark incident’ is now also widely referred to as the “Chinese Nth Room” (中国版N号房). The original Nth Room scandal made headlines in South Korea in August 2019, after the existence of a vast Telegram chat network involving blackmail, cybersex trafficking, and the distribution of sexually exploitative videos—run by South Korean men—was exposed.

But some argue that calling the Maskpark scandal the “Chinese Nth Room” oversimplifies the issue and obscures its broader scale.

“There isn’t just one Nth Room in China, there are many,” Weibo user Fanzhexi (@饭哲惜) wrote, compiling a list of digital sex scandals that have been labeled as “China’s Nth Room” in recent years.

Among them, the following incidents:

- 2019: Twitter users uncovered numerous Chinese-language accounts selling date-rape drugs. They launched a widespread campaign under the hashtag #ChinaWakeUp, hoping to draw attention from Chinese women and authorities. But these voices barely made it through China’s Great Firewall and eventually faded into silence.

- 2022: Weibo user Liangzhou (@梁州Zz) exposed an online child sexual exploitation forum with nearly 50000 members. This was a disturbingly active community sharing videos sexually exploiting underage girls, even with detailed tactics on how to lure victims using sweet words and small gifts.

- 2023: BBC Eye released a documentary titled Catching a Pervert: Sexual Assault for Sale, following a year-long investigation into a public molestation and hidden-camera sexual exploitation ring run by a group of young Chinese men living in Japan. The filmmakers even tracked down the ringleaders, whose identities were later published on Chinese social media platforms.

- 2024: Chinese netizens uncovered a paid website streaming live feeds from pinhole cameras. Rumors circulating on Weibo suggested the platform had as many as 140,000 members. The revelation sparked fierce online debate, yet no major media outlets covered the story—and once again, authorities remained silent.

And all of this is still only scratching the surface, leading to growing public questions about why those responsible haven’t been brought to justice.

This is also one of the reasons why some online commentators think that this digital sex scandal, as well as previous ones, shouldn’t be lumped under the “Chinese Nth Room” label.

After the scandal broke in South Korea, politicians and authorities swiftly acted to step up against these kinds of crimes. A special task force was set up, suspects were arrested, and stricter laws were introduced to crack down on secret filming and the distribution of exploitative videos.

In contrast, online commenters argue, recent years have shown that Chinese authorities have responded with less urgency and toughness to similar crimes, such as in the cases mentioned above.

“I was the one being secretly filmed”

Another major issue fueling the whirlwind of emotion and anger on Chinese social media is the censorship of articles, comments, hashtags, and posts related to ‘Maskpark Gate.’ The story is being kept off trending search lists, and searching #maskpark# or #麦梓豪# (Mai Zihao) on Weibo returns the message: “Sorry, this topic content cannot be displayed.”

Since awareness of the case has been driven by online sleuths, concerned netizens, and female victims, their goal is to amplify their voices so that authorities will take action.

But instead of being heard, they see their posts getting deleted—while seeing no progress in how the case is being handled.

“I’ve lost faith,” one user despairingly posted on Weibo “It feels like we’re stuck in a vicious cycle: anger, helplessness, forced forgetting, and then anger again. The harm has been done multiple times, but there’s been no progress.”

Others are beginning to feel a sense of apathy, questioning whether continuing to raise awareness even makes a difference. One Xiaohongshu user wrote: “We just endlessly pass along broken bits to those who already broke it into pieces. Eventually, there’s nothing left for us to break. Once it turns to dust, a gust of wind will blow it all away.”

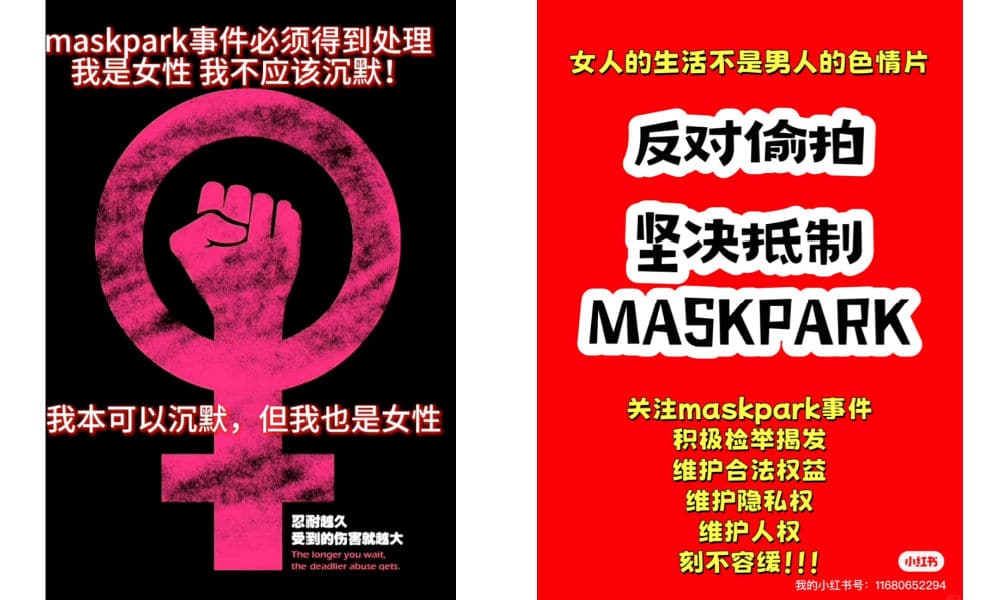

Some have turned to creating digital art and letting the images speak for them.

Digital art spread online. Right image by 菠萝菠萝咪, left image original creator unknown.

By now, the case feels like the elephant in the room across platforms like Weibo, Douyin, and Xiaohongshu, where many are left wondering: who is actually standing up against sexual exploitation and for women’s safety?

Examples of protest images and digital posters on Chinese social media.

One protest sign says: “Women’s lives are not a porn movie for men. Fight against secret filming. Stand up against Maskpark.”

Another protest phrase is “The one who was secretly recorded is me” (“被偷拍的就是我”), suggesting that every woman is potentially a victim of Maskpark. Those who haven’t been alerted have no way of knowing if they’re among the thousands of videos and images circulating within the community.

Others point out that this scandal reveals how advanced and precise hidden camera technologies have become, making this not just a women’s issue but a national problem.

Waiting for Karma

A major aspect of the Maskpark scandal is the shocking way thousands of Chinese men used their own female family members, friends, and colleagues as content to “offer tributes” to the Telegram group—exposing those they were meant to protect.

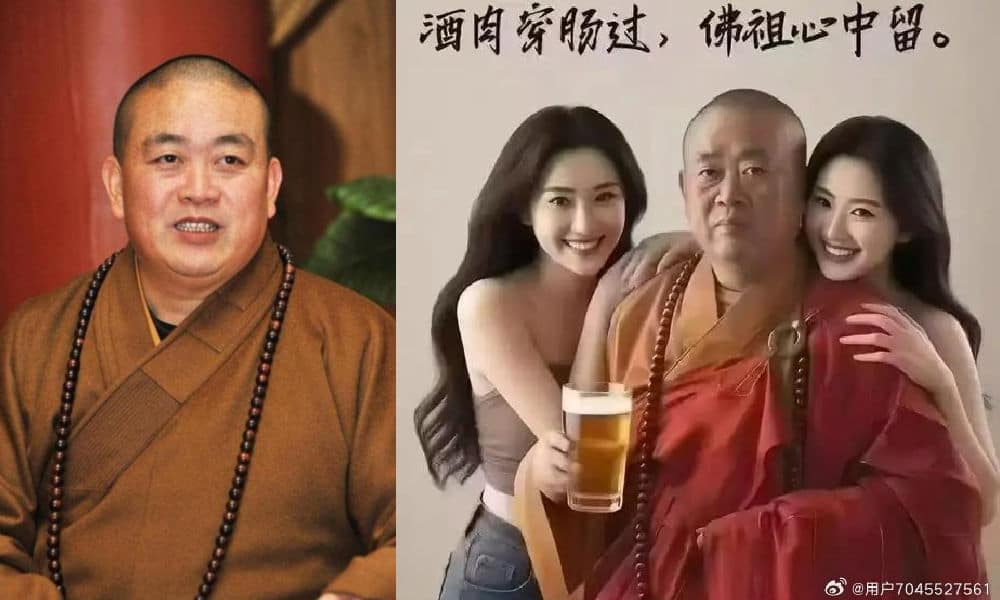

In another scandal dominating Chinese social media this week, one of the country’s well-known Buddhist monks—Shi Yongxin (释永信), the abbot of the world-famous Shaolin Temple—was revealed to be a money-grabbing playboy who embezzled temple funds, had multiple affairs, and fathered illegitimate children.

Shi Yongxin, who also was an active Weibo user sharing Buddhist wisdoms, had been at the Shaolin Temple since 1981. In our latest featured article, we explore how the controversy unfolded and what has happened since.

Left: image of Shaolin abbot Shi Yongxin. Right: AI/photoshopped image made by netizens saying: “Alcohol and meat goes through th stomach, Buddha remains in the heart.”

Though entirely different in nature, both the Maskpark and Shaolin scandals have been called just “the tip of the iceberg” (冰山一角) by netizens who believe these events represent far broader, systemic problems.

One part of the Shaolin scandal that has raised discussions is that one of Shi Yongxin’s disciples, Shi Yanlu (释延鲁), had already tried to raise the alarm about the abbot’s ethical, monastic, and financial misconduct ten years ago. Together with fellow monks, Shi Yanlu submitted a fifty-page formal complaint detailing the abbot’s fraudulent behavior and sexual misconduct in 2015.

However, the Henan provincial investigation concluded that the accusations lacked evidence, and no action was taken, allowing Shi Yongxin to continue a temple career marked by embezzlement and affairs for another decade.

People therefore feel that Shi Yongxin’s fall from his Buddhist throne is just one part of the story — there was a structure in place that kept him in power for many years, protected by those in various positions who turned a blind eye to his wrongdoings.

The Shi Yongxin scandal has negatively impacted public perception of monasteries and monks across China. If a monk in such a high and influential position could stray so far from the Buddhist path, what does that say about the rest? Where do temple donations go? Have Chinese temples become mere “chessboards for capital” (资本的棋盘), as one person wondered, where dirty games are played on the backs of believers?

Both the Maskpark incident and the Shaolin scandal reveal that nothing feels sacred anymore — not a woman’s privacy in a public bathroom, not a monk’s vows in a sacred temple.

If there’s one thing that remains, though, it’s karma.

In the case of Shi Yongxin, commenters wrote that karma has come for him (“如今他的因果报应终于来了”); he’s been stripped of his title, arrested, and is now awaiting the legal consequences of his misdeeds.

In the case of the key figures behind the Maskpark groups and all those men who “offered tributes,” netizens can only hope that karma will come for them, too.

– By Manya Koetse & Ruixin Zhang

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

Dear Reader

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

A look back at the three major phases of China’s social media — and why What’s on Weibo is evolving into Eye on Digital China.

Published

1 month agoon

November 12, 2025

This edition of the Eye on Digital China newsletter by Manya Koetse was sent to premium subscribers. Subscribe now to receive future issues in your inbox.

“Do you still remember going to the internet cafe, paying 2 yuan ($0.30) per hour during the day or 7 yuan ($1) for an all-nighter? Staying up playing games and surfing around?”

It’s the kind of content you’ll often see today on platforms like Douyin or Bilibili — nostalgic videos showing smoky internet cafes (wangba 网吧) from the early 2000s, where people chatted on QQ or played World of Warcraft on old Windows PCs while eating instant noodles. These clips trigger waves of nostalgia, even among internet users too young to remember that era themselves.

Internetcafe in 2005, image via 021zhaopin.com

The current nostalgia wave you see on Chinese social media is indicative of how China’s digital world has evolved over the past 25 years, shifting from one era to the next.

As I welcome a new name for this newsletter and say goodbye to ‘Weibo Watch’— and, in the longer run, to the ‘What’s on Weibo’ title, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic myself. It seems like a good moment to look back at the three major stages of Chinese social media, and at the reason I started What’s on Weibo in the first place.

1. The Blogging Boom (2002–2009): The Early Rise of Chinese Social Media

When I first came to China and became particularly interested in its online environment, it was the final phase of the early era of Chinese social media — a period that followed soon after the country had laid the foundations for its internet revolution. By 1999, the first generation of Chinese internet giants — Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Sina — had already been founded.

China’s blogging era began with the 2002 launch of the platform BlogChina.com (博客中国), followed by a wave of new platforms and online communities, among them Baidu Tieba and Renren. By around 2005, there were roughly 111 million internet users and 16 million bloggers, and the social impact was undeniable. 2005 was even dubbed China’s “year of blogging.” 1

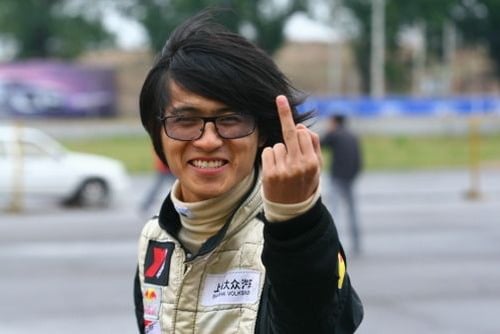

Chinese writer Han Han (韩寒, born 1982), a high-school-dropout-turned–rally car racer, became one of the most-read figures on the Chinese internet with his sharp and witty blogs. He was just one among many who rose to fame during the blog era, becoming the voice of China’s post-1980s youth.

The rebel of China’s blog era, Han Han, became of voice of his generation.

When I moved to Beijing in 2008, I had a friend who was always out of money and practically lived in an internet cafe in the city’s Wudaokou district, not far from where I studied. We would visit him there as if it were his living room — the wangba was a local hangout for many of us.

Not only online forums and blogging sites were flourishing at the time, but there was also instant messaging through QQ (腾讯QQ), online news reading, and gaming. Platforms like the YouTube equivalents Tudou (土豆) and Youku (优酷) were launched, and soon Chinese companies began developing more successful products inspired by American digital platforms, such as Fanfou (饭否), Zuosa (做啥), Jiwai (叽歪), and Taotao (滔滔), creating an online space that was increasingly, and uniquely, Chinese.

That trajectory only accelerated after 2009, when popular Western internet services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, became inaccessible from within mainland China.

⚡ The launch of Sina Weibo in 2009 came at a crossroads for China’s social media landscape: it was not only a time when many foreign platforms exited China, but also when internet cafes faced major crackdowns.

As a foreigner, I don’t think I ever visited internet bars in Beijing anymore by that point — internet use had largely shifted to home connections. Laptop ownership was rising, and we all had (pre-smartphone) mobile phones, which we used to text each other constantly, since texting was cheaper than calling.

Some of the mobile phones in China’s 2009 top 10 lists.

Weibo came at just the right time. It filled the vacuum left by the online crackdowns across China’s internet while still benefiting from the popularity of blogging. Weibo (微博), after all, literally means “micro-blog” — micro because the number of characters was limited, just like Twitter, making short-form posts the main way of communication.

Weibo quickly became hugely successful, for many more reasons than just timing. Its impact on society was so palpable that its trending discussions often seeped into everyday conversations I had with friends in China.

In English-language media, I kept reading about what was being censored on the Chinese internet, but that wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to know — I also wanted to know what was on Weibo, so I could keep up with my social circles.

That question planted the seed for What’s on Weibo: the simple curiosity of “What are people talking about?” What TV series are popular? What jokes and controversies are everyone discussing (but that I never fully grasped)? I wanted to get a sense of an online world that was, in many ways, intangible to outsiders — including myself. As I had moved back to Europe by then, it was also a way for me to stay connected to those everyday conversations unfolding online in China.

With scissors, glue, and some paper, I started sketching out what a future website might look like.

Papercrafting the idea for a website named ‘What’s on Weibo’ in 2012.

And in March 2013, after doing my best to piece it together, I launched What’s on Weibo and began writing — about all kinds of trends, like the milk powder crisis, about China’s many unmarried “leftover men” (shengnan 剩男), and about the word of the moment, “Green Tea Bitch” (lǜchá biǎo 绿茶婊) — a term used to stereotype ambitious women who act sweet and innocent while being seen as calculating or cunning.

2. From Weibo to the Taobao Moment: China’s Mobile Social Era: (2010–2019)

Around 2014–2015, people started saying Weibo was dead. In fact, it hadn’t died at all — some of its most vibrant years were still ahead. It had simply stumbled into the mobile era, along with China’s entire social media landscape.

As mobile internet became more widespread and everyone started using WeChat (launched in 2011), new mobile-first platforms began to emerge.2 In 2012–2013, for example, apps like Toutiao and Xiaohongshu (小红书, RED) were launched as mobile community platforms. With the rapid rise of China’s new tech giants — Bytedance, Meituan, and Didi — a new mobile era was blossoming, leaving the PC-based social media world far behind.

Spending another summer in Beijing in 2014, I called it the “Taobao Moment” — Taobao being China’s most successful online marketplace, a platform for buying and selling practically everything from clothes and furniture to insurance and even Bitcoins. At the time, I thought Taobao captured everything Beijing was at that moment: a world of opportunities, quick decisions, and endless ways to earn and spend money.

On weekends, some of my friends would head to the markets near the Beijing Zoo to buy the latest dresses, purses, jeans, or shoes. They’d buy stock on Saturday, do a photo shoot on Sunday, and sell the goods online by Monday. You could often spot young people on the streets of Beijing staging their own fashion shoots for Taobao — friends posing as models, Canon cameras in hand.

During that period, What’s on Weibo gradually found its audience, as more people became curious about what was happening on Chinese social media.

Around 2016, Weibo entered another prime era as the “celebrity economy” took off and a wave of “super influencers” (超级红人) emerged on the platform. Papi Jiang stood out among them — her humorous videos on everyday social issues made her one of China’s most recognizable online personalities, helping to drive Weibo’s renewed popularity.

Witty Papi Jiang was a breath of fresh air on Weibo in 2016.

People were hooked on social media. Between 2015 and 2018, China entered the age of algorithm- & interest-driven multimedia platforms. The popularity of Kuaishou’s livestreaming and Bytedance’s Douyin signaled the start of an entirely new era.

3. The New Social Era of AI-fication and Diversification (2020–Current)

China’s social media shifts over the past 25 years go hand in hand with broader technological, social, and geopolitical changes. Although this holds true elsewhere too, it’s especially the case in China, where central leadership is deeply involved in how social media should be managed and which direction the country’s digital development should take.

Since the late 2010s, China’s focus on AI has permeated every layer of society. AI-driven recommendation systems have fundamentally changed how Chinese users consume information. Far more than Weibo, platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu have become popular for using machine-learning algorithms to tailor feeds based on user behavior.

China’s social media boom has put pressure on traditional media outlets, which are now increasingly weaving themselves into social media infrastructure to broaden their impact. This has blurred the line between social media and state media, creating a complex online media ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s not just AI and media convergence that are reshaping China’s online landscape — social relationships now dominate both information flows and influence flows. 3 Not everyone is reading the same headlines anymore; people spend more time within their own interest-based niches. It’s no longer about microblogging but about micro-communities.

China now has 1.12 billion internet users. Among new users, young people (aged 10–19) and the elderly (60+) account for 49% and nearly 21%, respectively. The country’s digital environment has never been more lively, and social media has never been more booming.

As a bit of a dinosaur in China’s social media world, Weibo still stands tall — and its trending topics still matter. But the community that was once at the heart of the Chinese internet has dispersed across other apps, where people now engage in more diverse ways than ever.

In China, I notice this shift: where I once saw the rise of Weibo, the Taobao boom, or the Douyin craze, I now see online and offline media increasingly converging. Social media shapes real-life experiences and vice versa, and AI has become integrated into nearly every part of the media ecosystem — changing how content is made, distributed, consumed, and controlled.

In this changing landscape, the mission of What’s on Weibo — to explain China’s digital culture, media, and social trends, and to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online spaces — has stayed the same. But the name no longer fits that mission.

Over the past few years, my work has naturally evolved from Weibo-focused coverage to exploring China’s digital culture through a broader lens. The analysis and trend updates will continue, but under a new name that better reflects a time when Weibo is no longer at the center of China’s social media world: Eye on Digital China.

For you as a subscriber (subscribe here), this means you can expect more newsletter-based coverage: shorter China Trend Watch editions to keep you up to date with the latest trends, along with other thematic features and ‘Chapter’ deep dives that explore the depth behind fleeting moments.

For now, the main website will remain What’s on Weibo, but it will gradually transition into Eye on Digital China. I’ll keep the full archive alive — more than twelve years of coverage that helps trace the digital patterns we’re still seeing today. After all, the story of China’s past online moments often tells us more about the future than the trends of the day.

Thank you for following along on this new journey.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 Liu, Fengshu. 2011. Urban Youth in China: Modernity, the Internet and the Self. New York: Routledge, 50.

2 Mao Lin (Michael). 2020. “中国互联网25年变迁:两次跃迁,四次浪潮,一次赌未来” [25 Years of China’s Internet: Two Leaps, Four Waves, and a Gamble on the Future]. 人人都是产品经理 (Everyone Is a Product Manager), January 3. https://www.woshipm.com/it/3282708.html.

3 Yang, Shaoli (杨绍丽). 2025. “研判2025!中国社交媒体行业发展历程、重点企业分析及未来前景展望:随着移动互联网兴起,社交媒体开始向移动端转移 [Outlook for 2025! The Development History, Key Enterprises, and Future Prospects of China’s Social Media Industry: With the Rise of Mobile Internet, Social Media Has Shifted to Mobile Platforms].” Zhiyan Consulting (智研咨询), February 7. https://www.chyxx.com/industry/1211618.html.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in the comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient — we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo.

Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. Both feature the same new content — so you can subscribe or read wherever you prefer. If you’re already subscribed on one platform and would like to move your subscription over, just let me know and I’ll help you get set up.

© 2025 Manya Koetse. All rights reserved.

China Tech

How the “Nexperia Incident” Became a Mirror of China–Europe Tensions

From the Dutch invoking a Cold War–era law to Chinese narratives about Europe, this is what gives the Sino-Dutch “Nexperia incident” its extra weight.

Published

2 months agoon

October 14, 2025

🔥 This is premium content and also appeared in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

On the evening of October 12, while the Netherlands vs. Finland World Cup qualifier became a hot topic on Weibo (#荷兰4比0芬兰#), something else entirely made headlines — not about goals, but about chips.

Chinese company Wingtech Technology (闻泰科技) issued a statement saying that the Dutch government, citing national security concerns, had imposed global operational restrictions on Nexperia (安世半导体), a Dutch semiconductor company based in Nijmegen that has been wholly owned by the Chinese Wingtech conglomerate since 2019.

The Dutch government reportedly ordered a one-year freeze on strategic and governance changes across Nexperia on September 30, but the news only went trending on Chinese social media after Wingtech revealed the suspension (the topic became no 1 on Toutiao on Sunday).

Wingtech said that Nexperia’s Chinese CEO, Zhang Xuezheng (张学政), was also suspended, and that an independent, non-Chinese director was appointed who can legally represent the company.

That was ordered by a Dutch court following internal upheaval — Nexperia’s Dutch and German executives, including Legal Chief Ruben Lichtenberg, CFO Stefan Tilger, and COO Achim Kempe, filed a petition with the Dutch Enterprise Chamber requesting emergency measures to suspend Zhang and place the company’s shares under temporary court management. The court agreed (also see the Pekingnology newsletter by Zichen Wang, who was among the first to report on this issue).

The next day, on October 13, Dutch newspapers reported on the freeze, describing it as a rare move. NRC called it “an emergency measure intended to prevent chip-related intellectual property from leaving the country,” adding that, according to insiders, “there were indications that Nexperia was planning to transfer chip know-how to China.”

The Dutch government later clarified that the so-called Goods Availability Act (Wet Beschikbaarheid Goederen) was applied “following recent and acute signals of serious governance shortcomings and actions within Nexperia,” to protect Dutch and European economic security and safeguard crucial technological knowledge.

That specific law dates back to the Cold War era of 1952 and, according to Pim Jansen, professor of economic administrative law at Erasmus University Rotterdam, has never been invoked before. (Due to the unique situation, Jansen almost wanted to dub it the “Nexperia law.”)

🇳🇱 Nexperia (安世半导体) is a spin-off from chipmaker NXP, which in turn originated from Royal Philips. The company produces basic semiconductors that are used everywhere, from phones to cars. Since becoming independent in 2017, its headquarters in Nijmegen has expanded from about 150 to nearly 500 employees. Across its production sites in Germany, the UK, and Asia, Nexperia employs more than 10,000 people.

🇨🇳 Wingtech Technology (闻泰科技) is a major Chinese tech conglomerate listed on the A-share market and based in Jiaxing, combining two core businesses: semiconductors and electronics manufacturing. The company started in 2005 as a smartphone design and assembly firm (ODM) serving brands such as Xiaomi, Samsung, and Lenovo, and has since become one of the world’s largest mobile device manufacturers.

The recent developments are a big blow to Wingtech, as it basically means won’t be able to control day-to-day decisions at its most valuable subsidiary.

According to Wingtech, the suspension is politically motivated rather than fact-based and constitutes a serious violation of the market economy principles, fair competition, and international trade rules that the EU itself advocates.

The Wider Tech War Context

The Nexperia news is not an isolated case – it comes at a time when many things are happening at once.

🧩 On October 1, Dutch media reported that, due to tightening export rules announced by the United States, no American parts or software can be sold to Nexperia without a US license anymore because Nexperia’s Chinese parent company, Wingtech, is already on the American “Entity List,” and all of the company’s subsidiaries now also fall under the extended US export restrictions that took effect on September 29.

🧩 According to a Dutch media report on October 2, Nexperia said it strongly disagreed with the new export restrictions and was working on measures to limit their impact on its operations.

🧩 Barely two weeks prior, on September 18, China banned its tech companies from buying Nvidia AI chips from the American Nvidia, citing antitrust and national security reasons.

🧩 As of October, China also added several prominent Western companies to its Unreliable Entity List, including the Canadian-based research firm TechInsights.

🧩 And, as if that all wasn’t enough, China dramatically expanded its rare earth export controls on Thursday, expected to have a direct impact on the global semiconductor supply chain, while President Trump announced 100% tariffs on all Chinese imports and new export controls on “any and all critical software.”

👉 Regardless of how directly all these events are connected to what has happened in the Netherlands, one thing is clear: the global tech war is intensifying, with control over the semiconductor ecosystem now a top strategic priority.

And whatever the exact reasons or details behind the freeze of Nexperia’s strategic operations, on Chinese social media the move is being framed within a broader narrative — that of Western containment aimed at curbing China’s rapid rise as a global technological power.

Chinese Social Media Responses

On Chinese social media, commentators are denouncing the Netherlands.

One finance-focused Weibo blogger (@董指导挤出俩酒窝) wrote:

💬✍️ “By 2024, Nexperia contributed 14.7 billion RMB (2 billion U.S. dollars) in revenue and nearly 40% gross profit margin [to the Dutch economy]. According to Wingtech’s data, it also paid 130 million euros in corporate income tax to the Netherlands (..) This should have been a textbook case of mutual success – Chinese capital brought markets and vitality; the Netherlands benefited from taxes and employment; technology continued to grow in value within the global supply chain. Yet the Netherlands, showing its “pirate spirit”, destroyed this successful example with its own hands..”

That sentiment — that the Netherlands is treating China unfairly despite Chinese contributions to the Dutch economy and business — was echoed across social media. On the Q&A platform Zhihu, some users called it “a dramatic story”:

💬✍️ “Wingtech spent hundreds of billions of yuan to acquire a long-established European semiconductor company, thinking it had finally gained access to core global technology. But before long, others pulled the rug out from under them, right in front of the whole world.”

Commenter Yan Yaofei (晏耀飞) said:

💬✍️ “It’s like you bought a cow and keep it in someone else’s barn — you tell them how to feed and use it, and they have no right to interfere. Then suddenly, they lock you out of the barn entirely. It basically can be classified as robbery, openly and shamelessly.”

Another Weibo commenter (@就是赵老哥) wrote:

💬✍️ “It feels like the Netherlands is making a fuss. Back then, they sold us a loss-making company and now they’re backing out. This will have a big impact on the semiconductor sector. Foreign companies are unreliable, even when you buy their companies, they’re still unreliable. Domestic substitution is the only way forward.”

Alongside mistrust toward the West and perceptions that the Netherlands has treated China unfairly, even betraying it, many online discussions also frame the move as part of a broader political provocation. At the same time, a recurring theme on social media is the belief that China must strengthen its domestic semiconductor industry.

Finance blogger Tengteng’s Dad (@腾腾爸) wrote:

💬✍️ “The Dutch government’s freezing of the shares of Wingtech Technology’s Dutch subsidiary reminds me of the Ping An–Fortis incident years ago. Europe hasn’t changed, it’s still the same shameless Europe. It’s just that my fellow countrymen have thought too highly of them, thanks to all those “public intellectuals” who have spent years diligently promoting their Western masters. Now, more and more Chinese people are opening their eyes. In the future, all that Western talk about democracy, rule of law, and freedom will completely lose its appeal in China.”

Chinese Narratives of Europe

The online reactions to the Nexperia incident echo broader Chinese narratives about Europe that have been circulating in the digital sphere for the past decade.

Last Thursday, the topic of Chinese narratives of Europe happened to be the main theme of a panel I joined during the ReConnect China Conference in The Hague, hosted by the Clingendael China Centre (event page).

In preparation for this event, I focused mostly on the social media angle of these narratives. I looked at hundreds of trending topics related to Europe from different Chinese platforms—from Kuaishou to Weibo—with a dataset of nearly 100 pages filled with hashtags that went viral over the past twelve months (October 2024–October 2025), to see what themes dominate discussions about Europe in China’s online sphere.

Excluding sports-related topics (which account for about 35–40% of all high-ranking posts about Europe; sports apparently are the best diplomacy tools, after all), the top 250 non-sports topics reveal a clear image of how Europe is perceived in Chinese digital discourse today.

A brief overview:

🟧 1. Energy, Russia, Sanctions, War, Security (≈ 38%)

🔍 Main Focus: Russia–Ukraine war, Europe’s energy crisis, loss of autonomy, European geopolitical vulnerability and dependence on the United States

💡 Main Theme: Europe is often portrayed as lacking strategic autonomy and bearing the heavy costs of decisions driven by Washington’s agenda. It is viewed as vulnerable and “losing out” (吃亏), strategically outmaneuvered & excluded from major geopolitical decision-making.

🟧 2. Economy, Trade, Technology (≈ 21%)

🔍 Main Focus: ASML, tensions over electric vehicles (EVs) and protectionism, supply chains, trade deficits, and deindustrialization

💡 Main Theme: Europe’s trade frictions with China are portrayed as symptoms of Western decline and hypocrisy. The main story is that Europe’s economy is stagnating partly due to being overly protectionist and dependent on the US, while China emerges as a more dynamic and vital global player. Europe is losing competitiveness while China rises as a tech innovator.

🟧 3. EU Politics and Governance (≈ 13%)

🔍 Main Focus: Internal EU divisions, populism, leadership crises, and Europe’s political rightward shift (右倾)

💡 Main Theme: The EU is depicted as disunited and inefficient, struggling to respond to global challenges. The focus is on its inability to achieve strong, unified leadership amid political instability and ideological fragmentation.

🟧 4. Society, Migration, Crime (≈ 11%)

🔍 Main Focus: Social instability, migration, public safety, and racial or cultural tension

💡 Main Theme: Europe is seen as unsafe, chaotic, and socially divided. This is often contrasted with China’s image of order and security.

🟧 5. Culture, History, Sino-European Relations (≈ 10%)

🔍 Main Focus: Cultural comparisons, debates on values, and reflections on historical ties

💡 Main Theme: While Europe is respected for its rich cultural heritage and moral legacy, it is also mocked for its perceived sense of moral superiority. Europe stands for the past glory of civilization, not its future.

🟧 6. Lifestyle, Tourism, Memes (≈ 7%)

🔍 Main Focus: Chinese tourism in Europe, theft incidents, travel diaries, humorous cross-cultural comparisons, and the growing sentiment of being “suddenly disillusioned with Europe” (对欧洲祛魅了)

💡 Main Theme: Europe remains a popular travel destination, but the online tone has shifted from overwhelming admiration to a more pragmatic and critical perspective. The image of Europe is now more “de-romanticized,” with some even suggesting that “getting robbed is part of the experience” [of traveling in Europe] (I previously wrote about that here).

From Chips to Goals

So what does this all tell us?

Beyond the idea that Europe—caught between Washington and Moscow—lacks the agency to handle external crises while also struggling with internal division and decline, the dominant Chinese narrative about Europe is actually not about Europe at all.

‘Europe’ is all about China. Representations of Europe—from “democratic disillusion” to danger, disorder, and dependency—serve as both a mirror and a warning against which Chinese social, political, and national narratives are contrasted: chaos vs. order, fragmentation vs. unity, vulnerable dependency vs. strategic autonomy, decline vs. rise, etc. etc.

Something that the hashtags don’t tell us as much, but is still very much alive as well, is that Europe is also still seen as a major market of opportunities and a crucial soft power frontier for China.

Europe’s future, therefore (and for other reasons), matters to China—not as a model to follow, but as a stage for Chinese cultural and economic influence, where Chinese products, culture, and ideas can shape global appeal.

Perhaps that’s also what gives the Nexperia incident its extra weight: it ties together multiple narratives. Europe is seen as overly protectionist, biased against China, and driven by Washington’s agenda — and the fact that former Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, now NATO Secretary-General, once called US President Trump “daddy” fits into that perception. As some Weibo commenters joked: “Did their daddy make them do it?”

In the end, the takeaway for many commenters is that the incident serves as another “wake-up call for China”: a stark reminder of the need for technological self-reliance. And so, the discussion unfolds in such a way that, once again, it becomes more about China than about Europe — about China’s international strategies, its global rise, and the lessons to be learned, with the Netherlands as the current antagonist.

Thankfully, there was something to celebrate as well: the Netherlands won 4-0 in the popular match against Finland. Amidst all the talk about trade and tech, one popular sports blogger on Weibo vividly wrote about how the Dutch attack was in full force, about how all-time top scorer Memphis Depay led the offense brilliantly, how he helped the team secure a victory, and how the Netherlands “took control of their own destiny in the race to top the group.”

Whatever the future holds for Nexperia and the geopolitical drama surrounding it, at least we can count on the unifying power of football — where, even if only for 90 minutes, chips sit on the bench and netizens far apart in politics cheer for each other’s countries.

I’m not even an avid football fan, but suddenly, the 2026 World Cup (still months away) can’t come soon enough.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

When an Entertainment Scandal Gets Political: How Wong Kar-wai Survived a Nationalist Storm

China Trend Watch: Quiet Nationalism, Loud Statements, and Nanjing Memorial Day

He Qing, China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty”, Passes Away at 61

Why This Year’s Nanjing Memorial Day Felt Different

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral5 months ago

China Memes & Viral5 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital11 months ago

China Digital11 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

fred dijs

August 4, 2025 at 12:40 pm

best stuk weer… barstens vol informatie… en mooi open eind… ‘…hope that karma will come for them, too…’