Newsletter

Weibo Watch: Christmas in China Is Everywhere and Nowhere

Christmas is an interesting time in China: here are some must-knows about this merry and military time of the year.

Published

1 year agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #41

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Christmas in China: everywhere and nowhere

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Noteworthy – ‘It’s My Party’ book launch

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Goodbye, my lover

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Santa Bao

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – Scaring myself

Dear Reader,

Even before December arrived, malls, shops, and hotel lobbies across Chinese cities were already busy putting up Christmas decorations, ensuring that Christmas trees, snowmen, and reindeer would spread joy and festive season vibes.

Christmas seems to be everywhere in China-but nowhere at the same time. Throughout the years, Christmas has become more popular in China, but as a predominantly atheist country with a small proportion of Christians, the festival is far more about the commercial aspects of the holiday season—including shopping, promotions, decorations, and entertainment—than it is about the birth of Jesus Christ.

Christmas in China is generally perceived as a “foreign” or “Western” festival, and there have been ongoing concerns and social media discussions about whether the festivities associated with Christmas clash with traditional Chinese culture.

These dynamics make it clear that Christmas is an interesting time in China, so I’ll take this occasion to highlight some must-knows about Christmas in China.

1: In China, It’s Not Merry Christmas, but Military Christmas

Now that Christmas time is here, a different kind of message is emerging on Chinese social media, countering the festive spirit. Some recurring comments include:

•”It’s not Santa Claus who brings you a silent night—it’s Chinese soldiers! Salute to them!” (“给你带来平安的不是圣诞老人,而是中国军人! 致敬!”)

•”December 24 isn’t Silent Night; it’s the night of victory at the Chosin Reservoir.” (“12月24日不是平安夜,是长津湖战役胜利之夜。”)

•”China doesn’t celebrate Christmas! On our ‘Silent Night,’ we wrapped the U.S. military like dumplings!” (“中国人不过圣诞节!中国人的平安夜,包美军的饺子。”)

These statements reflect China’s complicated relationship with Christmas. Especially in recent years, Chinese state media and influential social media accounts have been promoting an alternative Christmas narrative, emphasizing that the peace and safety enjoyed in China today is not thanks to a Western “Father Christmas,” but rather the sacrifices and strength of China’s military forces.

The main argument propagated is that this time of year in China should not focus on Christmas or Santa Claus, but instead on commemorating the end of the Korean War and honoring the country’s soldiers.

In the context of the Korean War (1950-1953), December 24 marks the conclusion of the Second Phase Offensive (1950), which was launched by the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army against the United Nations Command forces–primarily U.S. and South Korean troops. The Chinese divisions’ surprise attack countered the ‘Home-by-Christmas’ campaign. This name stemmed from the UN forces’ belief that they would soon prevail, end the conflict, and be home well in time to celebrate Christmas. Instead, they were forced into retreat and the Chinese reclaimed most of North Korea by December 24, 1950.

Especially in recent years and in light of the launch of success of the blockbuster movie Battle at Lake Changjin and its sequel, there has been increased attention on the Chinese offensive at Chosin Reservoir. This battle has been framed as a decisive and glorious victory, turning the tide of the Korean War and reinforcing the military strength of the People’s Republic of China as a new global force to be reckoned with.

Various online posters posted on Weibo by various channels, reinforcing the message that China’s ‘Christmas’ should be about remembering the victory at the Chosin Reservoir.

This growing official narrative highlights the importance of this military history for Chinese national identity, offering a stark contrast to the traditionally Western themes of December 24. It underscores the message that this time in China should be about honoring the military, not celebrating imported festivities.

2: When Mao Canceled Christmas

A true communist wouldn’t celebrate Christmas, would they? To solve China’s ‘Christmas problem,’ all Christmas celebrations were canceled during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) under Mao Zedong as part of the fight against foreign influence and the complete abolishment of all religion and religious customs.

As described in Gerry Bowler’s book Christmas in the Crosshairs (2017), after Mao’s death in 1976 and the subsequent economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping, attitudes changed. A new consumer culture emerged and China began to open up to global influences, which included Western holidays like Christmas.

As Christmas slowly gained popularity in China, it took on a primarily secular and commercial identity. It first found its way into society in larger cities, such as Shanghai and Beijing, as businesses began incorporating a commercial Christmas theme into their winter promotions and activities. Foreign communities in China also contributed to the holiday’s visibility by organizing parties and events.

Foreign chains like Pizza Hut and Starbucks further added to the festive season. Many restaurants in larger cities began offering Christmas-themed menus featuring foods like cheese, baked bread, and chocolate. It soon became a tradition to see Christmas trees, Santa, and his reindeer at malls and shops.

Christmas in China is commercial and non-religious: shopping, food, and entertainment. Images posted on Weibo and Xiaohongshu.

But not everyone is happy about the growing popularity of this foreign holiday. Over the past ten to fifteen years, resistance to the further popularization of Christmas in China has increased.

For example, in December 2015, a group of Hunan high school students dressed in traditional Chinese clothing (hanfu) protested by holding red placards reading, “Boycott Christmas—don’t celebrate foreign festivals.”

In 2017, the city of Hengyang stirred controversy by ordering government officials and their families not to celebrate Christmas, calling it “spiritual opium.” Local authorities further warned Party members and officials they would face heavy fines for making or selling artificial snow.

At the time, Chinese state media suggested that although this was a local policy, it was part of a wider campaign against Christmas as people in other cities, including students and workers, had received a similar notices. Several media reported that some universities across China, including one in Shenyang, banned their students from celebrating Christmas.

This year, similar stories are emerging. One company in Dongying, Shandong, issued a notice this week strictly prohibiting employees from participating in Christmas-related activities. The notice reportedly stated that Christmas decorations were not allowed and that employees should not share any content related to “foreign holidays” on their social media (#山东一公司禁止员工过圣诞节#).

In this way, it seems that Mao’s ban on Christmas still resonates nearly five decades later.

3: China as the World’s Christmas Factory

There is some irony in the efforts to replace Christmas narratives with stories of China’s military victories, or in the broader resistance to the presence of Christmas in China—both in its religious and commercial forms.

Why? Because China, in fact, is the home of Christmas as we know it today. Whether it’s the decorations on your tree, the toys underneath it, or the stockings by the fireplace, chances are they’re all “Made in China.”

In the Organizing Christmas (2024), author Philip Hancock highlights China’s critical role in the global Christmas economy. In particular, the town of Yiwu, in eastern Zhejiang Province, produces about 60% of the world’s Christmas decorations. It’s essentially Santa’s workshop brought to life.

With Christmas being serious business for around 600 local factories operating year-round, Yiwu has become known as the “Christmas Capital of the World.” While countries with Christian traditions focus on the spiritual aspects of the holiday, China handles the industrial and logistical side of Christmas.

Hancock also notes that beyond China’s position as the preeminent global manufacturer and exporter of Christmas-related goods and ornaments, the festival has gained increasing entertainment appeal among Chinese consumers.

In an effort to capitalize on the popularity of Finland’s Santa Park among Chinese tourists, the city of Chengdu once planned to build the world’s largest Santa-themed park—a 13-square-kilometer attraction dedicated to Santa Claus and his workshops. However, due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors, the plans were never realized. Still, as Hancock concludes, “the very fact that the project came so far attests to the popularity of Christmas in the country.”

Christmas may officially have no place in China, but in reality, it’s everywhere.

Lastly, in case you’re wondering: is it okay to sing Jingle Bells in China? Yes—but you might want to tweak the lyrics:

“Jī gōng bāo, jī gōng bāo, jīng guò wǒ de wèi”

(鸡公煲,鸡公煲,经过我的胃)

(“Chicken hot pot, chicken hot pot, passing through my stomach.”)

Sing it out loud and you’ll find it fits the tune perfectly and captures the fun (food-loving) spirit of Chinese Christmas! 😂

For those celebrating, I wish you a Merry Christmas. And for everyone, I hope these winter days bring you warmth and joy.🎄✨🌟🎄

I would like to thank Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang for their contributions to this newsletter.

Warm greetings,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

What’s New

The Disappearance of an MA Graduate | In this article, we explore the story that recently took Chinese social media by storm: the case of Ms. Bu, a once-promising Master’s graduate in Engineering, who was missing for 13.5 years. Her unexpected return brought an end to her family’s long and painful search but sparked the beginning of an online movement. Chinese netizens are not only demanding answers about how she could have remained missing for so long but are also seeking clarity regarding the puzzling inconsistencies in her story. Read on:

Her name is Bu Xiaohua | In this article, we delve deeper into the remarkable story Ms. Bu Xiaohua. Her case is more than just a mystery—it exposes systemic failures and sheds light on the vulnerabilities faced by women in rural China. Read more to unpack the key aspects of her story.

HPV case silenced | This case, also a major topic recently, has some connections to the Bu Xiaohua story. A 12-year-old girl from Shandong was diagnosed with HPV at a local hospital. When a doctor attempted to report the case, she faced resistance. Weibo users are now criticizing how the incident was handled.

What’s Trending

💥 What to Know about the Shenzhen Bay Explosion

The devastating explosion that occurred in a residential building in Shenzhen’s Nanshan District on December 11 has become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media this month. The incident took place just after 14:30 on the 28th floor of Building 1 of Shenzhen Bay Yuefu Phase II (深圳湾悦府二期), affecting multiple surrounding floors. Shortly after the explosion and subsequent fire, videos and images of the scene began flooding Weibo. Some were particularly harrowing—one video showed a woman sitting on the window frame with flames raging behind her. Tragically, she fell to her death. By late afternoon, the fire was fully extinguished. The explosion is suspected to have been caused by a gas leak, as some neighbors reported smelling gas prior to the incident.

Much of the online discussion surrounding the explosion has focused on the lack of safety measures and the inadequate enforcement of fire safety regulations during construction. The fire occurred in a building located in an affluent area, known for its luxury apartments with sky-high prices—some of the larger units reportedly sold for over 59 million yuan (more than $8 million USD). Moreover, the building is relatively new, having been completed between 2015 and 2018. If such a high-end residential complex is not safe, then what is?

The company behind the construction, Huarun Real Estate Management Company (华润物业公司), stated that they would fully cooperate with relevant government departments to handle the aftermath, provide assistance and care to the affected residents, and “overcome the difficulties together with them” (#华润物业回应深圳高层爆炸事故#). “It’s all a bunch of nonsense!” one netizen responded.

🛂 China Further Relaxing Visa Policies

China is further relaxing its visa-free policies. Last Tuesday, official channels announced that eligible foreign travelers from 54 countries, including Russia, Brazil, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada, who transit through China en route to a third country or region are now allowed to stay in China allowed stay in China for up to 240 hours, or 10 days, instead of the previous 72 to 144 hours.

The move, intended to attract more international visitors, took effect immediately. China has continuously optimized its transit visa exemption policies since it first opened its doors to foreign travelers after its stringent Covid policies. Now, China has unilaterally exempted visa requirements for travelers from 38 countries, and they recently extended the visa-free stay duration from the current 15 days to 30 days, to remain in effect until December 31, 2025.

🗣️ Trump All Over

He hasn’t even moved into the White House yet, but Trump is already a trending topic on Weibo these days. Whether it’s about him saying he has “a warm spot for TikTok” after being asked about the potential ban on the app, claiming that “China and the United States can together solve all the problems of the world,” smilingly telling an audience that Musk will never become president, reigniting the debate over Greenland, or vowing that the US will only recognize two genders (#特朗普承诺美国将只承认两种性别#), Trump has once again become a favorite topic on Chinese social media. It almost feels like we’re back in 2016.

Although Trump is a laughingstock for some netizens, I’ve also noticed waves of support for him on Weibo, with some calling him “clear-headed,” “savage,” and praising his ability to always make a “surprising” move.

📚 Smut Writer Update

We wanted to provide some updates about the erotic content writers we discussed previously (read here), as their final sentencing results were announced recently.

One of the authors convicted is Yunjian (云间), one of the more prominent writers of these sexually explicit web novels. As reported by Lianhe Zaobao, she was sentenced to 4 years and 6 months in prison for profiting from illegal activities. Some authors who were unable to gather funds to return illicit gains faced even longer sentences. On Weibo, some people are outraged over the severity of the punishment, especially since Yunjian reportedly earned no more than 2 million RMB (~$275,000) over several years of publishing. However, there are also some who defend the state’s crackdown on online “obscenities,” arguing that distributing such explicit content is a serious crime.

One commenter on Weibo wrote:

“I don’t want to describe works filled with hope as ‘obscene materials’ (淫秽物品). I don’t want to define the hard-earned income from creative efforts as ‘illegal earnings’ (赃款). I don’t want to reduce the warm and joyful exchanges between readers and authors to the act of ‘distributing obscene materials’ (传播淫秽物品). This is the most degrading and evil form of humiliation.”

🇺🇸 New York Subway Incident

The shocking incident of the woman going up in flames in the New York subway while people passed by is being widely discussed on Weibo (#美国一男子在地铁把一女子点燃#, #纽约地铁一男子在睡觉女子身上纵火#, #美国男子向地铁车厢睡觉女子纵火#). Noteworthy enough, some of the top comments on the incident are more about (foreign) perceptions of China than about the US: “(…) If this happened in China, it would trend for a week,” “This level of apathy is truly terrifying,” and “If something like this happened in China, it would be criticized from multiple angles: the lack of subway security checks, gender issues, and the apathy of bystanders.”

In the past, there have been many incidents in China where horrific things happened without people stepping in—such as the 2011 Foshan toddler incident—leading to widespread reflection, especially in foreign media, on how China’s socio-cultural and historical circumstances contributed to such incredible social apathy. The New York incident, sadly, shows that the ‘bystander problem’ is universal. Perhaps this will become New York’s “Foshan moment,” reflecting on how society has gone this far, this cold.

What’s Noteworthy

Earlier this month, I attended the celebration for the publication of the book It’s My Party: Tat Ming Pair and the Postcolonial Politics of Popular Music in Hong Kong by Yiu Fai Chow, Jeroen de Kloet, and Leonie Schmidt. I’d like to share it with you because it offers a fascinating account of the legendary Cantopop electronic duo Tat Ming Pair (達明一派), one of the most influential and groundbreaking bands in Hong Kong’s 1980s music scene.

Over the past decade, the politically engaged duo—Anthony Wong Yiu Ming and Tats Lau Yee Tat—have faced increasing suppression of dissent in Hong Kong under Beijing’s growing influence. Anthony Wong, in particular, has been a vocal supporter of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movements and an advocate for LGBTQ rights. His song “Memory Is a Crime,” commemorating the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown, exemplifies his commitment to challenging government suppression. However, spaces for critical voices in Hong Kong have been steadily shrinking. In 2019, all of Tat Ming Pair’s music was removed from Apple Music and other streaming platforms in mainland China. By January 2022, they were blacklisted by Hong Kong’s government-funded broadcaster RTHK, and their name is now censored on platforms like Weibo.

The book situates their music within the historical context of Hong Kong’s transition from British to Chinese rule, exploring how popular music can serve as a medium for cultural memory, resistance, and community building during times of political upheaval. While the hard copy of the book is priced at EUR 109.99, the digital version is available for free download via Springer here.

What’s Popular

Are you familiar yet with See You Again (再见爱人, literally: “Goodbye, Lover”)? It’s the Chinese reality show that EVERYBODY is talking about right now—each episode is sparking massive online discussions. If you’re looking for something to binge-watch this Christmas holiday, it’s available on YouTube with English subtitles (see link below).

Now in its fourth season, the show is produced by Mango TV (芒果TV) and follows three celebrity couples who are teetering on the edge of divorce. Through the course of the show, they attempt to reconcile with their partners by embarking on an 18-day journey—both figuratively, through honest discussions, and literally, by RV travel. Interestingly, the creators of the show drew inspiration from the movie Nomadland.

During this journey, the couples confront the issues that have been haunting their relationships, giving viewers a glimpse into their personal struggles. For instance, Liu Jishou (留几手) and Ge Xi (葛夕) candidly discussed their three-year lack of intimacy, a topic that quickly became a trending topic online.

Beyond the couples’ emotional trials and tribulations, this season has also caught viewers’ attention for the impeccable fashion choices displayed in the “observation room.” Panelists like Papi Jiang (Papi酱) and Pattie Hou (侯佩岑) have stood out for their simple yet chic and practical styles, providing plenty of inspiration for everyday wear. Their outfits have also become a goldmine for Taobao sellers, who are now promoting accessories like earrings and hats “similar to what’s worn in See You Again.”

What’s Memorable

Let’s remember how on Christmas Day 2018, Sina Weibo introduced a new festive emoticon based on Lei Bao (雷豹), the iconic character from the 1990s comedy film Hail the Judge (九品芝麻官). Played by actor Xu Jinjiang (徐锦江), Lei Bao’s red costume, white beard, and bushy eyebrows bear a resemblance to Santa Claus.

Weibo Word of the Week

I Scare Myself | Our Weibo phrase of the week is 自己吓自己 (zì jǐ xià zì jǐ), which translates to ‘scaring oneself.’

This popular catchphrase originates from a line in the recently released animated film The Mermaid’s Summer (美人鱼的夏天). The movie tells the story of Xiao Ai, a mermaid who transforms into a human and embarks on a series of misadventures far more challenging than she ever imagined.

Created by independent filmmaker Shen Xiaoyang (沈晓阳) from Xiamen, the film took over seven years to complete. Its first trailer debuted online in 2022, and the film premiered last month.

Despite the extended production time and a marketing campaign that built up expectations, public reception was underwhelming at best. The movie faced widespread ridicule for its awkward pacing and peculiar voice acting. Some critics went so far as to call it the “biggest joke in domestic animation of the year.”

The phrase 自己吓自己 (zì jǐ xià zì jǐ) comes from an unintentionally comedic scene in the movie. In the scene, Xiao Ai walks by the water when a sudden gust of wind causes her to sense danger coming from nearby bushes. She nervously brushes it off, saying the now-iconic line, “啊呵呵呵自己吓自己” (“Ah-hehe~ hehe~ scaring myself”) in a lifeless tone—only to be ambushed moments later and thrown into the river by a mysterious man in black.

This moment became an instant hit on platforms like Douyin, Xiaohongshu, and Bilibili and catapulted the phrase into meme territory as a moment of abract humor, inspiring countless parodies and spin-offs. Even well-known influencers, such as the “City Bu City” guy Paul Mike Ashton, reenacted the scene on social media. To date, there are hundreds of reinterpretations, including dialect versions, pet reenactments, and everyday life parodies.

Parodies on Xiaohongshu.

‘I scared myself’ has gone beyond the animated movie scene, it’s now a funnily ‘non-dramatic dramatic’ way to react to unexpected events in your surroundings.

Amid the criticism surrounding the film, Shen Xiaoyang has reportedly withdrawn from all social media platforms. However, there’s a silver lining: the viral fame of the phrase has brought the flopped film renewed attention and modest box office gains.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

Dear Reader

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

A look back at the three major phases of China’s social media — and why What’s on Weibo is evolving into Eye on Digital China.

Published

3 months agoon

November 12, 2025

This edition of the Eye on Digital China newsletter by Manya Koetse was sent to premium subscribers. Subscribe now to receive future issues in your inbox.

“Do you still remember going to the internet cafe, paying 2 yuan ($0.30) per hour during the day or 7 yuan ($1) for an all-nighter? Staying up playing games and surfing around?”

It’s the kind of content you’ll often see today on platforms like Douyin or Bilibili — nostalgic videos showing smoky internet cafes (wangba 网吧) from the early 2000s, where people chatted on QQ or played World of Warcraft on old Windows PCs while eating instant noodles. These clips trigger waves of nostalgia, even among internet users too young to remember that era themselves.

Internetcafe in 2005, image via 021zhaopin.com

The current nostalgia wave you see on Chinese social media is indicative of how China’s digital world has evolved over the past 25 years, shifting from one era to the next.

As I welcome a new name for this newsletter and say goodbye to ‘Weibo Watch’— and, in the longer run, to the ‘What’s on Weibo’ title, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic myself. It seems like a good moment to look back at the three major stages of Chinese social media, and at the reason I started What’s on Weibo in the first place.

1. The Blogging Boom (2002–2009): The Early Rise of Chinese Social Media

When I first came to China and became particularly interested in its online environment, it was the final phase of the early era of Chinese social media — a period that followed soon after the country had laid the foundations for its internet revolution. By 1999, the first generation of Chinese internet giants — Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Sina — had already been founded.

China’s blogging era began with the 2002 launch of the platform BlogChina.com (博客中国), followed by a wave of new platforms and online communities, among them Baidu Tieba and Renren. By around 2005, there were roughly 111 million internet users and 16 million bloggers, and the social impact was undeniable. 2005 was even dubbed China’s “year of blogging.” 1

Chinese writer Han Han (韩寒, born 1982), a high-school-dropout-turned–rally car racer, became one of the most-read figures on the Chinese internet with his sharp and witty blogs. He was just one among many who rose to fame during the blog era, becoming the voice of China’s post-1980s youth.

The rebel of China’s blog era, Han Han, became of voice of his generation.

When I moved to Beijing in 2008, I had a friend who was always out of money and practically lived in an internet cafe in the city’s Wudaokou district, not far from where I studied. We would visit him there as if it were his living room — the wangba was a local hangout for many of us.

Not only online forums and blogging sites were flourishing at the time, but there was also instant messaging through QQ (腾讯QQ), online news reading, and gaming. Platforms like the YouTube equivalents Tudou (土豆) and Youku (优酷) were launched, and soon Chinese companies began developing more successful products inspired by American digital platforms, such as Fanfou (饭否), Zuosa (做啥), Jiwai (叽歪), and Taotao (滔滔), creating an online space that was increasingly, and uniquely, Chinese.

That trajectory only accelerated after 2009, when popular Western internet services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, became inaccessible from within mainland China.

⚡ The launch of Sina Weibo in 2009 came at a crossroads for China’s social media landscape: it was not only a time when many foreign platforms exited China, but also when internet cafes faced major crackdowns.

As a foreigner, I don’t think I ever visited internet bars in Beijing anymore by that point — internet use had largely shifted to home connections. Laptop ownership was rising, and we all had (pre-smartphone) mobile phones, which we used to text each other constantly, since texting was cheaper than calling.

Some of the mobile phones in China’s 2009 top 10 lists.

Weibo came at just the right time. It filled the vacuum left by the online crackdowns across China’s internet while still benefiting from the popularity of blogging. Weibo (微博), after all, literally means “micro-blog” — micro because the number of characters was limited, just like Twitter, making short-form posts the main way of communication.

Weibo quickly became hugely successful, for many more reasons than just timing. Its impact on society was so palpable that its trending discussions often seeped into everyday conversations I had with friends in China.

In English-language media, I kept reading about what was being censored on the Chinese internet, but that wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to know — I also wanted to know what was on Weibo, so I could keep up with my social circles.

That question planted the seed for What’s on Weibo: the simple curiosity of “What are people talking about?” What TV series are popular? What jokes and controversies are everyone discussing (but that I never fully grasped)? I wanted to get a sense of an online world that was, in many ways, intangible to outsiders — including myself. As I had moved back to Europe by then, it was also a way for me to stay connected to those everyday conversations unfolding online in China.

With scissors, glue, and some paper, I started sketching out what a future website might look like.

Papercrafting the idea for a website named ‘What’s on Weibo’ in 2012.

And in March 2013, after doing my best to piece it together, I launched What’s on Weibo and began writing — about all kinds of trends, like the milk powder crisis, about China’s many unmarried “leftover men” (shengnan 剩男), and about the word of the moment, “Green Tea Bitch” (lǜchá biǎo 绿茶婊) — a term used to stereotype ambitious women who act sweet and innocent while being seen as calculating or cunning.

2. From Weibo to the Taobao Moment: China’s Mobile Social Era: (2010–2019)

Around 2014–2015, people started saying Weibo was dead. In fact, it hadn’t died at all — some of its most vibrant years were still ahead. It had simply stumbled into the mobile era, along with China’s entire social media landscape.

As mobile internet became more widespread and everyone started using WeChat (launched in 2011), new mobile-first platforms began to emerge.2 In 2012–2013, for example, apps like Toutiao and Xiaohongshu (小红书, RED) were launched as mobile community platforms. With the rapid rise of China’s new tech giants — Bytedance, Meituan, and Didi — a new mobile era was blossoming, leaving the PC-based social media world far behind.

Spending another summer in Beijing in 2014, I called it the “Taobao Moment” — Taobao being China’s most successful online marketplace, a platform for buying and selling practically everything from clothes and furniture to insurance and even Bitcoins. At the time, I thought Taobao captured everything Beijing was at that moment: a world of opportunities, quick decisions, and endless ways to earn and spend money.

On weekends, some of my friends would head to the markets near the Beijing Zoo to buy the latest dresses, purses, jeans, or shoes. They’d buy stock on Saturday, do a photo shoot on Sunday, and sell the goods online by Monday. You could often spot young people on the streets of Beijing staging their own fashion shoots for Taobao — friends posing as models, Canon cameras in hand.

During that period, What’s on Weibo gradually found its audience, as more people became curious about what was happening on Chinese social media.

Around 2016, Weibo entered another prime era as the “celebrity economy” took off and a wave of “super influencers” (超级红人) emerged on the platform. Papi Jiang stood out among them — her humorous videos on everyday social issues made her one of China’s most recognizable online personalities, helping to drive Weibo’s renewed popularity.

Witty Papi Jiang was a breath of fresh air on Weibo in 2016.

People were hooked on social media. Between 2015 and 2018, China entered the age of algorithm- & interest-driven multimedia platforms. The popularity of Kuaishou’s livestreaming and Bytedance’s Douyin signaled the start of an entirely new era.

3. The New Social Era of AI-fication and Diversification (2020–Current)

China’s social media shifts over the past 25 years go hand in hand with broader technological, social, and geopolitical changes. Although this holds true elsewhere too, it’s especially the case in China, where central leadership is deeply involved in how social media should be managed and which direction the country’s digital development should take.

Since the late 2010s, China’s focus on AI has permeated every layer of society. AI-driven recommendation systems have fundamentally changed how Chinese users consume information. Far more than Weibo, platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu have become popular for using machine-learning algorithms to tailor feeds based on user behavior.

China’s social media boom has put pressure on traditional media outlets, which are now increasingly weaving themselves into social media infrastructure to broaden their impact. This has blurred the line between social media and state media, creating a complex online media ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s not just AI and media convergence that are reshaping China’s online landscape — social relationships now dominate both information flows and influence flows. 3 Not everyone is reading the same headlines anymore; people spend more time within their own interest-based niches. It’s no longer about microblogging but about micro-communities.

China now has 1.12 billion internet users. Among new users, young people (aged 10–19) and the elderly (60+) account for 49% and nearly 21%, respectively. The country’s digital environment has never been more lively, and social media has never been more booming.

As a bit of a dinosaur in China’s social media world, Weibo still stands tall — and its trending topics still matter. But the community that was once at the heart of the Chinese internet has dispersed across other apps, where people now engage in more diverse ways than ever.

In China, I notice this shift: where I once saw the rise of Weibo, the Taobao boom, or the Douyin craze, I now see online and offline media increasingly converging. Social media shapes real-life experiences and vice versa, and AI has become integrated into nearly every part of the media ecosystem — changing how content is made, distributed, consumed, and controlled.

In this changing landscape, the mission of What’s on Weibo — to explain China’s digital culture, media, and social trends, and to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online spaces — has stayed the same. But the name no longer fits that mission.

Over the past few years, my work has naturally evolved from Weibo-focused coverage to exploring China’s digital culture through a broader lens. The analysis and trend updates will continue, but under a new name that better reflects a time when Weibo is no longer at the center of China’s social media world: Eye on Digital China.

For you as a subscriber (subscribe here), this means you can expect more newsletter-based coverage: shorter China Trend Watch editions to keep you up to date with the latest trends, along with other thematic features and ‘Chapter’ deep dives that explore the depth behind fleeting moments.

For now, the main website will remain What’s on Weibo, but it will gradually transition into Eye on Digital China. I’ll keep the full archive alive — more than twelve years of coverage that helps trace the digital patterns we’re still seeing today. After all, the story of China’s past online moments often tells us more about the future than the trends of the day.

Thank you for following along on this new journey.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 Liu, Fengshu. 2011. Urban Youth in China: Modernity, the Internet and the Self. New York: Routledge, 50.

2 Mao Lin (Michael). 2020. “中国互联网25年变迁:两次跃迁,四次浪潮,一次赌未来” [25 Years of China’s Internet: Two Leaps, Four Waves, and a Gamble on the Future]. 人人都是产品经理 (Everyone Is a Product Manager), January 3. https://www.woshipm.com/it/3282708.html.

3 Yang, Shaoli (杨绍丽). 2025. “研判2025!中国社交媒体行业发展历程、重点企业分析及未来前景展望:随着移动互联网兴起,社交媒体开始向移动端转移 [Outlook for 2025! The Development History, Key Enterprises, and Future Prospects of China’s Social Media Industry: With the Rise of Mobile Internet, Social Media Has Shifted to Mobile Platforms].” Zhiyan Consulting (智研咨询), February 7. https://www.chyxx.com/industry/1211618.html.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in the comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient — we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo.

Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. Both feature the same new content — so you can subscribe or read wherever you prefer. If you’re already subscribed on one platform and would like to move your subscription over, just let me know and I’ll help you get set up.

© 2025 Manya Koetse. All rights reserved.

China Media

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Published

10 months agoon

March 30, 2025

“This man is doing God’s work. In just six hours, he eliminated all Western media propaganda about China,” Chinese influencer Li Sanjin (李三金) said in one of his videos this week. The man he referred to, allegedly doing ‘God’s work,’ is the American YouTuber and online streamer Darren Watkins, better known as IShowSpeed or Speed, who visited China this week and livestreamed from various locations.

With 37 million followers on his YouTube account, Watkins’ visit hasn’t exactly flown under the radar. His streams from China have already accumulated over 17.5 million views on YouTube alone, and he also became the talk of the week on Chinese social media.

In China, the 20-year-old IShowSpeed is known as Jiǎkànggē (甲亢哥), or “Hyper Bro,” since the immensely popular YouTube star is known for being highly energetic.

Although IShowSpeed is originally known for soccer and gaming-related content, he’s been streaming live from various countries over the past year, from Ecuador to Bolivia, from Australia to Indonesia, from Romania to Japan, and also from the Netherlands, where a mob of fans harassed the YouTuber to such an extent that the influencer fled and panicked, until the police intervened and asked him to shut down the livestream for safety reasons — which he did not comply with.

It was not the only time IShowSpeed’s visit got chaotic. He also got into trouble during livestreams from other countries. While streaming from Norway, he injured his ankle and was swarmed by a crowd while trying to get out. In Greece and Indonesia, he had to ask for police support as well. In Thailand, he crashed a tuk-tuk into a temple wall.

In China, IShowSpeed’s livestreams went far more smoothly, and netizens, state media, and other official channels raved about his visit and its favorable portrayal of the country and its culture.

🔹 Symbol of Cultural Exchange & Positive Diplomacy

“Jiǎkànggē” became one of the viral terms of the week, on Weibo, Kuaishou, Douyin, and Toutiao. During his China trip, the livestreamer hit several YouTube milestones — not only breaking the 37 million subscriber mark while on stream, but also surpassing the magic number of 10 million views in total.

Watkins, also known for being (sometimes aggressively) loud and chaotic, suddenly emerged as a symbol of cultural exchange and positive diplomacy. The past week saw hashtags such as:

#️⃣”IShowSpeed gives young foreigners a full-window view into China” (#甲亢哥给国外年轻人开了全景天窗#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed’s Shanghai livestream breaks Western filter on China” (#甲亢哥上海直播打破西方对中国滤镜#)

#️⃣”American influencer IShowSpeed amazed by stable wifi on China’s high-speed train” (#美国网红甲亢哥被高铁稳定网络震惊#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed praised deep tried tripe for being incredibly delicious” (#甲亢哥赞爆肚太好吃了#), or

#️⃣ “IShowSpeed bridges the cultural divide” (#甲亢哥弥合文化鸿沟#).

While in Chinese media, Watkins was lauded for shining a positive light on China, this message was also promoted on English-language social media, where he was praised by the Chinese embassy in the US (#驻美大使馆称赞甲亢哥中国行#), writing:

Post by Chinese Embassy in the US on X, March 26.

“This 20-year-old American internet star is bridging cultural gaps through digital means and creating new channels for foreign audiences to better understand China.”

So what exactly did IShowSpeed do while in China?

On March 24, Watkins livestreamed from Shanghai. He wandered around the city center, visited a KFC, danced with fellow streamers, stopped by a marriage market, ate noodles, played ping-pong, had hotpot, joined a dragon dance group and got acquainted with some traditional Chinese opera performance, and walked along the Bund.

On March 26, he streamed from Beijing, starting in Donghuamen before briefly entering the Forbidden City—dressed in a Dongbei-style floral suit. He later took a stroll around Nanluoguxiang and the scenic Houhai lake, rode a train, and finally visited the Great Wall, where he did backflips.

In his stream on March 28, Watkins traveled to Henan to visit the famous Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng, hoping to find a master to teach him kung fu. He trained with Shaolin monks—footage that quickly went viral.

Lastly, on March 29, he opened his own Weibo account and published his first post. On Douyin, he shared a video of his visit to Fuxi Mountain in Zhengzhou, featuring the popular “Stairway to Heaven” tourist spot.

On social media, many viewers were captivated by the content. One major talking point was the remarkably strong internet connection that allowed him to livestream for six-hour stretches without losing signal in Shanghai. (Though his Beijing stream started off patchier, the drop was minor.) For many, it symbolized the quality of China’s 5G services.

Foreign viewers also praised how safe, friendly, and clean the country appeared, and how his streams highlighted various aspects of Chinese culture—from everyday people to traditional arts and local cuisine.

🔹 Telling & Spreading China’s Stories Well

It is no wonder the success of the Jiǎkànggē livestreams is celebrated by Chinese official media in an age where China’s foreign communication aims to increase China’s international discourse power, shaping how the world views China and making that image more credible, more respectable, and more lovable.

That’s not just an observation — it’s an official strategy. Introduced by Xi Jinping in 2013, “Telling China’s Story Well” (“讲好中国故事”) is a political slogan that has become a key propaganda strategy for China and continues to be a priority in finding different ways of promoting Chinese culture — new ways of telling China’s story in the social media age – while countering Western dominant narratives about China.

In increasingly digitalized times, it is not just about telling China’s story well, but also spreading China’s message effectively — preferably through genuine and engaging stories (Cai 2013; Qiushi 2021).

Especially young, non-official ‘storytellers’ can make China’s image more relatable and dynamic. One major example, highlighted in a 2022 case study by Zeng Dan (曾丹), is Chinese influencer Li Ziqi (李子柒). You’ve probably heard of her, or seen snippets of her videos: she creates soothing, cinematic content depicting China’s countryside lifestyle, focused on cooking, crafts, and gardening. With 26 million followers on YouTube, Li Ziqi became a viral sensation who successfully communicated an authentic and appealing ‘China story’ to a broad global audience.

Li Ziqi in one of her YouTube videos.

Although the calm and composed Li Ziqi and the loud, chaotic IShowSpeed couldn’t be more different, they have some things in common: both have large international fanbases, including their millions of YouTube subscribers; they offer perspectives that differ from Chinese state media or official channels; and they have the capacity not just to tell China’s story well, but to spread it effectively through videos and livestreams.

🔹 Spontaneous Stream or Scripted Propaganda?

IShowSpeed’s China streams have triggered a wave of responses from fans and viewers, sparking discussions across international social media and even making newspaper headlines.

In English-language online media spheres, there appear to be a range of perspectives on Watkins’ China trip:

📌 One prominent view—also echoed by various foreign influencers on YouTube and other platforms—is that IShowSpeed’s visit counters “Western media lies” about China and has successfully shown the “real China” through his livestreams. The Shanghai-based media outlet Radii claimed that “IShowSpeed’s China Tour is doing more for Chinese Soft Power than most diplomats ever could.”

📌 Others challenge this narrative, questioning which dominant Western portrayals of China IShowSpeed has actually disproven. Some argue that the idea of China being a “bleak place with nothing to do where people live in misery” is itself a false narrative, and that presenting IShowSpeed’s livestreams as a counter to that is its own form of propaganda (see: Chopsticks and Trains).

📌 There are also those who see Watkins’ trip as a form of scripted propaganda. To what extent were his livestreams planned or orchestrated? That question has become one of the central points of debate surrounding the hype around his visit.

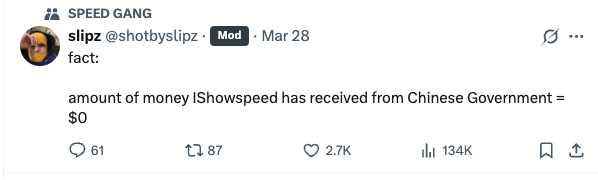

These rumors have been addressed by cameraman Slipz (@shotbyslipz), who took to X on March 28, 2025. Slipz posted that the team is “(..) not making political content, not any documentary and no journalism,” and later added: “Fact: amount of money IShowSpeed has received from Chinese Government = $0.”

But does the fact that IShowSpeed did not receive money from the Chinese government mean that it wasn’t also a form of China promotion?

➡️ Organized — it definitely was. Any media trip in China has to be. IShowSpeed would have needed a visa, he had translators with him, and throughout the streams it’s evident that local guards and public security officers were present, walking alongside and helping to keep things under control, especially in crowded areas and at major tourist spots — from Nanjing Road in Shanghai to an entire group of guards seemingly accompanying the entourage in the Forbidden City.

One logistical “advantage” to his visit was the fact that YouTube is blocked in China. While some Chinese fans do bypass the Great Firewall to access the platform, IShowSpeed remains far less known in China than in many other countries — a factor that likely contributed to how smoothly the streams went and helped prevent chaos. The team also launched a Douyin account during the trip, where he now has over two million followers. (To stream directly to their 37 million followers on YouTube, Watkins’ team either needed a VPN to access WiFi or had arranged roaming SIM cards to stay connected.)

➡️ Was it staged? Many parts clearly weren’t: casual public conversations, spontaneous barber visits in both Shanghai and Beijing (with barbers looking unsure of how to handle the situation), and wholesome fan encounters. There was even a moment when Watkins walked into a public restroom and forgot to mute the sound.

But other parts of the trip were undeniably staged — or at least framed to appear spontaneous. When visiting a marriage market in Shanghai, for instance, two actors appeared, including one woman with a sign stating she was looking for someone “capable of doing backflips.”

When Watkins took a “random” ride in what was described as the fastest car in China — the Xiaomi SU7 Ultra — the vehicle appeared to be conveniently parked and ready.

Similarly, when the streamer “ran into” Chinese-American TikTok influencer Miles Moretti (李美越) in Beijing, it turned out to be the person who would give him the now-iconic bright Dongbei flower suit and accompany him on his journey.

The ping-pong, the kung fu, the Peking opera, the hotpot, the Forbidden City tour — it all plays into the kinds of experiences that official channels also like to highlight. While likely planned by Watkins’ team in coordination with local partners, it was all far more orderly and tourism-focused than, for example, Watkins’ chaotic visit to the Netherlands.

Watkins and his entourage were also well-informed about the local dos and don’ts. At one point, Watkins even mentions “following the rules,” and when Moretti tells him mid-stream that “somebody very important lives on our left,” Watkins asks “Who?” — but the camera zooms out and the question goes unanswered, suggesting they may have been reminded that certain names or topics were off-limits (judge the moment for yourself here).

The livestream didn’t always go exactly the way Watkins wanted, either. When he attempted to take more random walks around the city, the crew appeared to be informed that some areas were off-limits, and he was asked to return to the car to continue the trip (clips here and here).

🔹 The “Nàge” Song

One major talking point surrounding IShowSpeed’s China livestreams was “the N-word.” No, not that N-word — but the Chinese filler word “nàge” or “nèige” (那个). Like “uhm” in English or “eto” in Japanese, “nàge” is a hesitation marker commonly used in everyday Mandarin conversation. It also functions as a demonstrative pronoun meaning “that.”

The word has previously stirred controversy because of its phonetic resemblance to a racial slur in English. In 2020, an American professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business was even temporarily suspended after using the word during an online communications class — some students misunderstood its context and took offense.

The word — and the song “Sunshine, Rainbow, White Pony” (阳光彩虹小白马) by Chinese singer Wowkie Zhang (大张伟), which repeatedly features the word nàge in its chorus — popped up multiple times during Watkins’ trip. The catchy tune essentially became the theme song of his visit.

The first nàge moment actually already appeared within the first five minutes of Watkins’ Shanghai stream, when a Chinese comedian approached him on the street, trying to recall a joke. “What?!” Watkins reacted, with laughter in the background. “That’s not a joke, you said n**! It’s my first five minutes in China!” he exclaimed, before patting the man’s back in a friendly gesture, clearly not offended.

🔄 It resurfaced again within the first hour when Watkins visited a marriage market and one of the performers sang the Wowkie Zhang song. Watkins initially acted shocked, then demanded they sing it again — only to burst out laughing and start singing along.

🔄 Later, he sang the song again with a street saxophonist and encouraged others to join in.

🔄 At other moments, he played up the drama again, feigning anger when a crowd broke into the chorus, and it became a recurring gag throughout the streams.

These incidents all seem staged. One of the main reasons Watkins is known to many netizens in China is because of an older video clip showing his exaggerated reaction to the nàge song — dating back to at least 2022. So while it may have looked spontaneous, Watkins was already familiar with the word and the viral song long before his China trip.The attention given to the nàge ‘controversy’ was likely amplified for views and engagement.

While Watkins was clearly in on this part of the show — as with others — he also seemed genuinely, and at times amusingly, unaware of many things in China. He repeatedly referred to RMB as “dollars,” mistook elderly women for retired YouTube streamers, and even assumed that a woman livestreaming near the Forbidden City was reading his chat and trying to collaborate with him — although she seemed totally uninterested and was just minding her own business.

🔹 A Win-Win Situation

In the end, IShowSpeed’s visit highlighted two sides effectively doing their job. Watkins and his team successfully arranged a YouTube trip that generated high ad revenue, attracted millions of new subscribers, and boosted his brand and global fame.

On the Chinese side, there was clearly coordination behind the scenes to ensure the trip went smoothly: avoiding controversy, ensuring safety, and showcasing positive aspects of Chinese culture. From traditional opera and kung fu to ping pong, IShowSpeed’s content gave center stage to the kinds of cultural highlights that align closely with China’s official narratives and tourism goals. Even if the government didn’t pay the YouTuber directly, as his team has emphasized (and there’s no reason to doubt them), the trip still fit seamlessly into China’s soft power strategy.

IShowSpeed’s China visit has created a unique media moment that resonates for several reasons: it’s the encounter of a young modern American with old traditional China; it is a streamer known for chaos visiting a nation known for control. And it brings different benefits to both sides: clicks and ad revenue for IShowSpeed, and free foreign-facing publicity for China.

No, IShowSpeed didn’t undo years of critical Western media coverage on China. But what his visit shows is that we’ve entered a phase where China is becoming more skilled at letting others help tell its story — in ways that resonate with a global, young, online audience. He didn’t do “God’s work.” He simply did what he always does: stream. And with China’s help, he streamed China very well.

There’s so much more I want to share with you this week — from Chinese reactions to the devastating Myanmar earthquake, to a recent podcast I joined with Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf (link in Dutch, for those interested). But it also happens to be my birthday today, and I’m really hoping to still grab some birthday hotpot — so I’ll wrap this up here. I’ll keep you informed on the other trends in the next newsletter.📨.

Best,

Manya

(@manyapan)

References:

Cai, Mingzhao 蔡名照. 2013. “Telling China’s Stories Well and Spreading China’s Voice: Thoroughly Studying and Implementing the Spirit of Comrade Xi Jinping’s Important Speech at the National Conference on Propaganda and Ideological Work [讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音——深入学习贯彻习近平同志在全国宣传思想工作会议上的重要讲话精神].” People’s Daily 人民日报, October 10. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1010/c1001-23144775.html. Accessed March 29.

Qiushi 求是网. 2021. “Xi Jinping: Telling China’s Story Well, Spread China’s Voice Well [习近平:讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音].” Qs Theory, June 6. http://www.qstheory.cn/zhuanqu/2021-06/02/c_1127522386.htm. Accessed March 29.

Zeng Dan 曾丹. 2022. “How to Tell China’s Story Well: Taking Li Ziqi as an Example [如何讲好中国故事——以李子柒为例].” Progress in Social Sciences 社会科学进展 4 (1): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.35534/pss.0401002.

What’s Featured

Quite terrifying and interesting, as this trending story touched upon so many different issues.

What started as a single snarky comment on Weibo spiraled into an online witch hunt, exposing not just some dark sides of online Kpop fandom but also, most importantly, the vulnerabilities in China’s digital privacy.

Read the story, the latest by Ruixin Zhang 👀

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment7 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West