China Arts & Entertainment

A Joke Too Far: 3 Social Media Views on Chinese Comedian Li Haoshi Getting Canceled over PLA Pun

From Weibo to WeChat, from Douyin to Zhihu, Li Haoshi’s joke has sparked widespread conversations, and opinions vary.

Published

2 years agoon

There is a delicate balance between humor and controversy, and Chinese comedian Li Haoshi recently discovered the consequences of crossing that line. In a punchline that took aim at China’s People’s Liberation Army, Li found himself at the center of a significant controversy. Is Li deserving of his ensuing cancellation? On Chinese social media, opinions are divided.

A Chinese comedian’s politically incorrect joke is the topic that everyone has been talking about this week, even making international headlines.

Li Haoshi (李昊石), a comedian who performed under the stage name ‘House’ with the famous Chinese comedy company Xiao Guo company (笑果文化), recently faced accusations of making offensive remarks towards the Chinese army during one of his shows. As a result, he has been subjected to a ban on social media platforms and has also been prohibited from participating in future performances.

The show in question took place on May 13th and while the performance officially was not allowed to be filmed, some attendees recorded the particular joke that caused controversy and then exposed House on social media. According to a Zhihu user who claimed to have secretly recorded the entire show, the joke went as follows:

“Shanghai is an international metropolis where everything is aligned with international standards. After I moved to Shanghai, I adopted two stray dogs. Strictly speaking, they weren’t stray dogs. We found them on a nearby mountain, and they were wild dogs. We can’t really say we rescued them because they were at the top of the food chain in the mountains and didn’t need our help. We were more like a makeover show, experiencing city life. These two dogs were indeed the top predators on the mountain. When I first saw them, it felt like I was witnessing a wildlife documentary. The two dogs would chase a squirrel like a missile launched into the air. Normally, when you see dogs, you find them cute, and your heart melts. You think of these words. But when I saw these two dogs, only eight words flashed in my mind: ‘Good discipline, capable of winning battles’ (作风优良, 能打胜仗). They were truly exceptional. I walked proudly on the streets of Shanghai with these two dogs. The only problem was that they had so much energy. My physical fitness couldn’t keep up.”

The triggering aspect of this joke lies in the eight words “zuò fēng yōu liáng, néng dǎ shèng zhàng” (“作风优良, 能打胜仗”: “Good discipline, capable of winning battles”). This slogan has long been associated with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (中国人民解放军, PLA) as a standard used to describe and motivate the army. The lines, used by Xi Jinping in 2013, are used together with another phrase, namely that of “tīng dǎng zhǐhuī” (“听党指挥”), meaning “to obey the Party’s command” or “follow the Party’s leadership,” together encapsulating the principles of the Chinese military.

“Obeying the Party’s command – Capable of winning battles – positive work ethic” – these famous phrases were used in a comical context by Chinese comedian House. (Image source).

Using the army’s slogan to describe two wild dogs is considered offensive to the PLA’s “sacred and inviolable” image.

The joke was considered such a serious faux pas that Party newspaper People’s Daily posted about it on social media platform Weibo two days later, claiming that performers in talkshows should be cautious with their words and be careful to stay within appropriate boundaries.

They also suggested that there should be consensus within the industry on where the bottom line is on which jokes can and cannot be made. People’s Daily used the phrase “tuōkǒu mò tuōguǐ, wán gěng xū yǒu dù” (“脱口莫脱轨,玩梗须有度”), which can be translated as: “Do not deviate when speaking freely, and use jokes [memes/punch lines] with moderation.”

The word used for ‘talkshow’ is tuōkǒuxiù 脱口秀, a Chinese term that literally translates to “talk show” but actually mostly refers to stand-up comedy shows and a type of popular form of entertainment in which performers showcase their humorous storytelling skills in an engaging and often improvisational manner.

Li Haosi’s controversial joke garnered more significant attention from Chinese state media. After People’s Daily initial post, they made another Weibo post addressing the issue. The post began with the hashtag “There is a sense of security called the soldier sons of the people” (#有一种安全感叫人民子弟兵#), which is a widely used phrase to describe the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and highlight the close relationship between the military and the Chinese people.

A second post by People’s Daily about the Li Haoshi controversy paid tribute to China’s PLA soldiers.

In the post, People’s Daily expressed their support for the PLA and condemned any action or statement that might be seen as disrespectful or offensive towards the military and the soldiers who serve as the guardians of the Chinese people (“人民子弟兵不容冒犯”). They tagged their post with the hashtag “People’s Daily Discusses ‘House’ Offending the Soldiers Sons of the People” (#人民日报评House冒犯人民子弟兵#), which has since received over 670 million views on Weibo.

As the controversy surrounding Li Haoshi escalated, fuelled in part by Chinese state media, it has also became a prominent topic of discussion among the general social media userbase. From Weibo to WeChat, from Douyin to Zhihu, Li Haoshi’s joke has sparked widespread conversations. Within these online discussions, there are three prominent and recurring viewpoints that we will explore here.

1: TOLERANCE & MORE FREEDOM OF SPEECH

“You ‘wolf warriors’ and ‘little pinkies’ are only good at conducting witch hunts! It is actually you who should be canceled.”

The notion of talk shows being regarded as “an art of offense” (“一种冒犯的艺术”) is widely discussed on Chinese social media these days. Evaluating the boundaries between ‘acceptable humor’ and ‘crossing the boundaries’ continues to be a topic of discussion, with some advocating for performers’ artistic freedom of expression and speech, arguing that “there is no offensive art, but all kinds of genuine art can be offensive.”

In a since-deleted WeChat article, one Chinese blogging account expressed readers’ concerns regarding the Li Haoshi controversy. A major concern raised was not just about freedom of expression for performers, but about freedom of expression within this topic itself, suggesting that the online discourse surrounding the ‘House controversy’ allows very limited space for actual debate and offers no opportunity for people to discuss the different perspectives of the story.

On Weibo, some individuals express similar concerns about the lack of nuance in the discussion. Apart from censorship or top-down control, they worry about a general discussion environment that leaves no space for opposing opinions. One person commented: “You ‘wolf warriors’ and ‘little pinkies’ are only good at conducting witch hunts! It is actually you who should be canceled.”

“The more people comment, the more extreme they get,” another person wrote. Meanwhile, the comment sections of various popular posts discussing the issue were either disabled or heavily filtered, to the extent that none of the 244 listed comments were visible.

2: CROSSING A RED LINE

“It is very simple. Making jokes is not the same as malicious slander.”

Many people do not agree with those advocating for a more tolerant approach to the Li Haoshi controversy. A seeming majority of Weibo users argue that ‘talk shows’ should not serve as a sanctuary for “inappropriate speech.” They assert that public speeches have inherent “bottom lines” that cannot be crossed. Performers should be aware of these existing red lines, and should not use their profession as an excuse to express problematic statements.

One popular blogger (@胜利主义章北海) argued that comedians are already well aware that they have certain boundaries; offending their audience would rob them of their income, and they are also careful not to insult their boss or colleagues: “They would not dare to [offend them]. They are conscious of these boundaries. So why would they dare to offend the PLA?”

Many agree with this stance: “It is very simple. Making jokes is not the same as malicious slander.”

In these online discussions, the United States is often cited as an example due to its strong emphasis on free speech. Some Chinese netizens note that even in the U.S. and other Western countries, there are also topics or jokes that would be considered off-limits and could lead to consequences such as being canceled.

The Weibo account “Xu Ji Observation” (@徐记观察, previously recognized for positive online content and the promotion of the “mass line”) mentions how some people in America were condemned for even hinting at disrespecting the military. American quarterback Tom Brady was widely criticized in 2021 after comparing playing football to military deployment, and Pete Davidson was slammed for making fun of an American representative and war veteran who had lost one eye during his deployment in Afghanistan. Both Brady and Davidson had to apologize.

Although many people agree with Xu Ji’s observation, others argue that the comparison is not entirely fair, as the consequences faced by Chinese performers who get ‘canceled’ go beyond a simple apology. In China, as exemplified by Li Haoshi’s current situation, an apology alone is unlikely to resolve the matter (read more about China’s canceled celebrities here).

3: ALWAYS HONOR OUR SOLDIERS

“”We can do without talk show hosts or celebrities, but we cannot do without our soldier sons of the people!”

There is also a large group of netizens who argue that this discussion should not be about ‘freedom’ versus ‘boundaries’ at all, but instead should focus on the mere fact that the Chinese comedian deliberately insulted the “soldier sons of the people,” and in doing so, committing a crime according to the “Heroes and Martyrs Protection Law.”

Although Chinese state media have led narratives surrounding this controversy in which they stress the ‘sacredness’ of the PLA, its mission, and duties, there are many netizens who say they feel the same. House’s joke has triggered anger among Chinese social media users who emphasize the dedication of the PLA and condemn any jokes targeting them.

In many online posts, bloggers highlight the heroic actions of the PLA in the past and, using patriotic images of soldiers with national flags, remind people about how they selflessly rescued people during the Wenchuan Earthquake or persistently guarded the South China Sea.

One popular comment said: “We can do without talk show hosts or celebrities, but we cannot do without our soldier sons of the people!”

While online discussions surrounding the Li Haoshi controversy are ongoing, Chinese authorities have concluded that the joke constitutes a legal violation. As of May 18th, House’s social media account has been suspended, he has been boycotted by the China Association of Performing Arts, and the Beijing Police have announced their intention to investigate the case due to House’s alleged “severe insult to the People’s Liberation Army during his performance, causing a highly negative societal impact.”

Furthermore, Xiao Guo, the company representing House, has received an official warning and has had over 1.35 million yuan ($190,000) in “illegal gains” confiscated, along with a fine of 13.35 million yuan ($1.8 million) imposed by the police. In response to this penalty, the company has canceled all scheduled performances in China and terminated their contract with Li Haoshi.

Read more related articles:

◼︎ “Love the Motherland” – New Moral Guidelines for Chinese Performers Come Into Force

◼︎ Chinese Comedian Li Dan under Fire for Promoting Lingerie Brand with Sexist Slogan

◼︎ Female Comedian Yang Li and the Intel Controversy

◼︎ 25 ‘Tainted Celebrities’: What Happens When Chinese Entertainers Get Canceled?

By Zilan Qian and Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

China Celebs

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Published

5 days agoon

June 27, 2025

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China this week. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Chinese beauty influencer and livestreamer Du Meizhu (都美竹) is facing online backlash this week after a former female fan filed a police report accusing her of scamming her out of nearly 200,000 yuan (approx. US$27,800).

The fan, known online as Sister Bing (Weibo handle @冰点人a冰点), has come forward with detailed allegations, claiming Du began swindling her in 2022.

Du Meizhu rose to national prominence in 2021 when she was 19 years old and became the first person to publicly accuse Chinese-Canadian pop star Kris Wu (吴亦凡) of rape and sexual misconduct. After at least 24 more victims also came forward, Wu was formally arrested on suspicion of rape in mid-August 2021 and was later sentenced to 13 years in prison.

It was around this time that ‘Sister Bing,’ whose real name is Ms. Zhu (朱, born 1979), started following Du Meizhu on social media. As a hard-working single mother of a daughter, she said she sympathized with Du and wanted to show her some support. In a Weibo post published in 2024, she detailed how Du Meizhu began noticing Zhu’s online interactions in early 2022 and added her as a friend on WeChat.

In private conversations, Du shared complaints about her difficult life, and as the two talked more and more, Zhu began transferring small amounts of money to help. Over time, Du said she needed money for various things—from financial support for school to legal disputes and expensive medical treatments for family members. Between 2022 and 2023, Zhu claims she transferred nearly 200,000 yuan in total.

At the end of 2023, Zhu–who works as a taxi driver–urgently needed money due to a family crisis. She reached out to Du to ask if she could repay the money. According to Zhu, she only returned 30,000 yuan (US$4,180) and refused to pay more, even though at the same time, Du was allegedly flaunting luxury brand purchases and had plans to buy a villa.

On June 25, 2025, Zhu posted an update on her Weibo account, saying she had traveled to Ulanhot City in Inner Mongolia – Du’s hometown – to seek justice and report the case to local authorities.

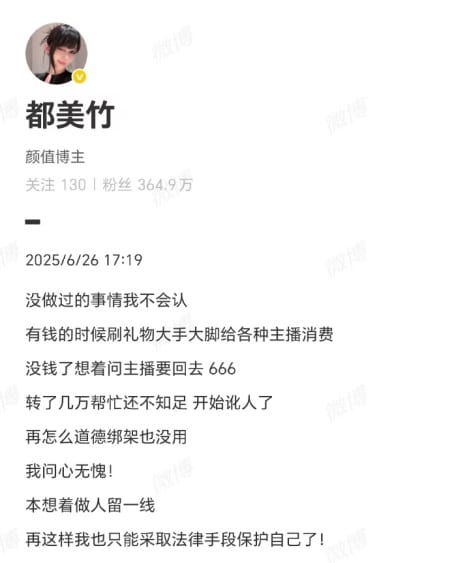

Du Meizhu has responded to the allegations on social media, writing that she “won’t admit to things I haven’t done.” She does not deny that Zhu gave her money.

She writes: “When she had money, she was lavishly spending it on gifts in all kinds of livestreams. Now that she’s broke, she wants it back from the streamers? After I transferred her thousands of yuan, she’s still not satisfied and is now starting to extort me. No amount of moral pressure will work. I have a clear conscience!”

The post by Du Meizhu

The case has blown up online. One post by Ms. Zhu has already received over 133,000 likes and is still gaining traction.

But the developments surrounding the case are puzzling to some. Du Meizhu has long maintained a social media image of wealth, showcasing a lifestyle filled with Dubai travel, horseback riding, luxury food, and fashion. Why would she need to take money from a single mum? Du is being criticized not only for faking her wealth, but also for accepting so much money from a woman who clearly needed the money for her own family.

Du Meizhu social media photos.

Although the story is attracting a lot of attention online because it exposes private conversations between Du and the woman – and, frankly, many netizens just enjoy the drama, – it also says a lot about China’s thriving livestreaming industry and just how close online followers can feel to the influencers they follow. In these kinds of online communities, it is common for fans and followers to send livestreamers money or ‘virtual gifts’.

In the case of Ms. Zhu, some netizens doubt that she can prove in court that she loaned Du the money instead of gifting it to her. People also criticize Zhu: why did she spend so much money on an online influencer instead of on her own daughter?

Either way, many Chinese netizens feel that it was not right of Du Meizhu to take advantage of a single mum like that. Even if she’s not legally wrong, they feel she lacks moral integrity.

Du’s most recent social media post—featuring her in so-called “old money fashion” outfits—has only added fuel to the fire. Dozens of commenters flooded the post with demands that she repay Ms. Zhu. Though Du seemingly tried to delete the negative comments, they kept pouring in. “At this rate, there won’t be any comments left,” one user wrote.

Whether or not Du Meizhu ultimately faces legal consequences, the backlash is already taking a toll. She might escape the courtroom, but won’t be able to escape the court of public opinion.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China ACG Culture

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Labubu is not ‘Chinese’ at all—and at the same time, it is very much a product of present-day China.

Published

3 weeks agoon

June 8, 2025

Labubu – the hottest toy of 2025 – is making headlines everywhere these days. The little creature is all over TikTok, and from New York to Bangkok and Dubai, people are lining up for hours to get their hands on the popular keyring doll.

In the UK, the Labubu hype has gone so far that its maker temporarily pulled the toys from all of its stores for “safety reasons,” following reports of customers fighting over them. In the Netherlands, the sole store where fans can buy the toys also had to hire extra security to manage the crowds, and Chinese customs authorities have intensified their efforts to prevent the dolls from being smuggled out of the country.

While the Labubu craze had slightly cooled in China compared to its initial peak, the character remains hugely popular and surged back into the top trending charts with the launch of POP MART’s Labubu 3.0 series in late April 2025 (which instantly sold out).

Following the global popularity of the Chinese game Black Myth: Wukong, state media are citing Labubu as another example of a successful Chinese cultural export—calling it ‘a benchmark for China’s pop culture’ and viewing its success as a sign of the globalization of Chinese designer toys.

But how ‘Chinese’ is Labubu, really? Here’s a closer look at its cultural identity and the story behind the trend.

The Journey to Labubu

In the perhaps unlikely case you have never heard of Labubu, I’ll explain: it’s a keyring toy with a naughty and, frankly, somewhat bizarre face and gremlin-like appearance that comes in various colors and variations. It’s mainly loved by young (Gen Z) women, who like to hang the toys on their bags or just keep them as collectibles.

The figurine is based on a character created by renowned Hong Kong-born artist Kasing Lung (龍家昇/龙家升, born 1972), whose work is inspired by Nordic legends of elves.

Kasung Lung, image via Bangkok Post.

Lung’s story is quite inspirational, and very international.

As a child, Lung immigrated to the Netherlands with his parents. Struggling to learn Dutch, young Kasing was given plenty of picture books. The picture books weren’t just a way to connect with his new environment, it also sparked a lifelong love for illustration.

Among Kasing’s favorite books were Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak and those by Edward Gorey — all full of fantasy, with some scary elements and artistic quality.

Later, as his Dutch improved, Kasing became an avid reader and turned into a true bookworm. The many fantasy novels and legendary tales he devoured planted the seed for creating his own world of elves and mythical creatures.

Kasing as a young boy on the right, and one of his children’s illustration books on the left.

After initially returning to Hong Kong in the 1990s, Lung later moved back to the Netherlands and eventually settled in Belgium.

Following a journey of many rejections and persistence, he began publishing his own illustrations and picture books for the European market.

Image via Sina.

In 2010, Hong Kong toy brand How2work’s Howard Lee reached out to Lung. One of How2work’s missions is cultivating creative talent and supporting the Hong Kong art scene. Lee invited Kasung to turn his illustrations into 3D, collectible figurines. Kasung, a collector of Playmobil figures since childhood, agreed to the collaboration for the sake of curiosity and creativity.

Lung’s partnership with How2work marked a transition to toy designer, although Lung also continued to stay active as an illustrator. Besides his own “Max is moe” (Max is tired) picture book, he also did illustrations for a series by renowned Belgian author Brigitte Minne (Lizzy leert zwemmen, Lizzy leert dansen).

A few years later, Lung introduced what would become known as The Monsters Trilogy: a fantasy universe populated by elf-like creatures. Much like The Smurfs, the Monsters formed a tribe of distinct characters, each with their own personalities and traits, led by a tribal leader named Zimomo.

With its quirky appearance, sharp teeth, and mischievous grin, Labubu stood out as one of the long-eared elves.

When Labubu Met POPMART

Although the Labubu character has been around since 2015, it took some time to gain fame. It wasn’t until Labubu became part of POP MART’s (泡泡玛特) toy lineup in 2019 that it began reaching a mass audience.

POP MART is a Chinese company specializing in artsy toys, figurines, and trendy, pop culture-inspired goods. Founded in 2010 by a then college student, the brand launched with a mission to “light up passion and bring joy,” with a particular focus on young female consumers (15-30 age group) (Wang 2023).

One of POP MART’s most iconic art toy characters—and its first major commercial success—is Molly, designed by Hong Kong artist Kenny Wong in collaboration with How2work.

Prices vary depending on the toy, but small figurines start as low as 34 RMB (about US$5), while collectibles can go as high as 5,999 yuan (US$835). Resellers often charge significantly more.

Pop Mart and its first major commercial success: Molly (source).

POP MART is more than just a store, it’s an operational platform that covers the entire chain of trendy toys, from product development to retail and marketing (Liu 2025).

Within a decade of opening it first store in Beijing, POP MART experienced explosive growth, expanded globally, and was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

The enormous success of POP MART has been the subject of countless marketing studies, drawing various conclusions about how the company managed to hit such a cultural and commercial sweet spot beyond its mere focus on female Gen Z consumers.

🎁 Gamifying consumption | One common conclusion about the success of POP MART, is that it offers more than just products—it offers an experience. At the heart of the brand is its signature blind box model, where customers purchase mystery boxes from specific product lines without knowing which item is inside. Those who are lucky enough will unpack a special ‘hidden edition.’ Originating in Japanese capsule toy culture, this element of surprise gamifies the shopping experience, makes it more shareable on social media, and fuels the desire to complete collections or hunt for rare figures through repeat purchases.

🌍 Creating a POP MART universe | Although POP MART has partnerships with major international brands such as Disney, Marvel, and Snoopy, it places a strong focus on developing its own intellectual property (IP) toys and figurines. In doing so, POP MART has created a universe of original characters, giving them a life beyond the store through things like collaborations, art shows and exhibitions, and even its own theme park in Beijing.

💖 Emotional consumption | What makes POP MART particularly irresistible to so many consumers is the emotional appeal of its toys and collectibles. It taps into nostalgia, cuteness, and aesthetic charm. The toys become companions, either as a desktop buddy or travel buddy. Much of the toys’ value lies in their role as social currency, driven by hype, emotional gratification, and a sense of social bonding and identity (Ge 2024).

The man behind POP MART and its strategy is founder and CEO Wang Ning (王宁), a former street dance champion (!) and passionate entrepreneur with a clear vision for the company. He consistently aims to discover the next iconic design, something that could actually rival Mickey Mouse or Hello Kitty.

In past interviews, Wang has discussed how consumer values are gradually shifting. The rise of niche toys into the mainstream, he says, reflects this transformation. Platforms like Douyin, China’s strong e-commerce infrastructure, and the digital era more broadly have all contributed to changing attitudes, where people are increasingly buying not for utility, but for the sake of happy moments.

While Wang Ning dreams of a more joyful world, he also knows how to make money (with a net worth of $20.3 billion USD, it was actually just announced that he’s Henan’s richest person now)—every new artist and toy design under POP MART is carefully researched and strategically evaluated before being signed.

Labubu’s journey before its POP MART partnership had already shown its appeal: Kasing Lung and How2Work had built a small but loyal fanbase pre-2019. But it was through the power of POP MART that Labubu really reached global fame.

Labubu: Most Wanted

Riding the wave of POP MART’s global expansion, Labubu became a breakout success, eventually evolving into a global phenomenon and cultural icon.

Now, celebrities around the world are flaunting their Labubus, further fueling the hype—from K-pop star Lisa Manobal to Thai Princess Sirivannavari and Barbadian singer Rihanna.

In China, one of the most-discussed topics on social media recently is the staggering resale price of the Labubu dolls.

Third edition of the beloved Labubu series titled “Big into energy” (Image via Pop Mart Hong Kong).

“The 99 yuan [$13.75] Labubu blind box is being hyped up to 2,600 yuan [$360]” (#99元Labubu隐藏款被炒至2600元#), Fengmian News recently reported.

Labubu collaborations and limited editions are even more expensive. Some, like the Labubu x Vans edition, originally retailed for 599 yuan ($83) and are now listed for as much as 14,800 yuan ($2,055).

Recently, Taiwanese singer and actor Jiro Wang (汪东城) posted a video venting his frustration over scalpers buying up all the Labubus and reselling them at outrageous prices. “It’s infuriating!” he said. “I can’t even buy one myself!” (#汪东城批Labubu黄牛是恶人#).

One Weibo hashtag asks: “Who is actually buying these expensive Labubus?” (#几千块的Labubu到底谁在买#).

Turns out—many people are.

Not only is Labubu adored and collected by millions, an entire subculture has emerged around the toy. Especially in China, where Labubu was famous before, the monster is now entering a new phase: playful customization. Fans are using the toy as a canvas to tell new stories and deepen their emotional connection, transforming Labubu from a collectible into a DIY project.

Labubu getting braces and net outfits – evolving from collectible to DIY project.

There’s a growing trend of dressing Labubu in designer couture or dynastic costumes (Taobao offers a wide array of outfits), but fans are going further—customizing flower headbands, adorning their dolls with tooth gems, or even giving them orthodontic braces for their famously crooked teeth (#labubu牙套#).

In online communities, some fans have gone as far as creating dedicated generative AI agents for Labubu, allowing others to generate images of the character in various outfits, environments, and scenarios.

Labubu AI by Mewpie.

It’s no longer just the POP MART universe—it’s the Labubu universe now.

“Culturally Odorless”

So, how ‘Chinese’ is Labubu really? Actually, Labubu is not ‘Chinese’ at all—and at the same time, it is very much a product of present-day China.

🌍 Not Chinese at all

Like other famous IP characters, from the Dutch Miffy to Japan’s Pikachu and Hello Kitty, Labubu is “culturally odorless,” a term used to refer to how cultural features of the country of invention are absent from the product itself.

The term was coined by Japanese scholar Koichi Iwabuchi to describe how Japanese media products—particularly in animation—are designed or marketed to minimize identifiable Japanese cultural traits. This erasure of “Japaneseness” helped anime (from Astro Boy to Super Mario and Pokémon) become a globally appealing and commercially successful cultural export, especially in post-WWII America and beyond.

Moreover, by avoiding culturally or nationally specific traits, these creations are placed in a kind of fantasy realm, detached from real-world identities. Somewhat ironically, it is precisely this neutrality that has made Japanese IPs so distinctively recognizable as “Japanese” (Du 2019, 15).

Many Labubu fans probably also don’t see the toy as “Chinese” at all—there are no obvious cultural references in its design. Its style and fantasy feel are arguably closer to Japanese anime than anything tied to Chinese identity.

When a Weibo blogger recently argued that Labubu’s international rise represents a more powerful example of soft power than DeepSeek, one popular reply asked: “But what’s Chinese about it?”

🇨🇳 Actually very Chinese

Yet, Labubu is undeniably a product of today’s China—not necessarily because of Kasing Lung (Hong Kong/Dutch/Belgian) or How2work (Hong Kong), but because of the Beijing-based POP MART.

Wang Ning’s POP MART is a true product of its time, inspired by and aligned with China’s new wave of digital startups. From Bytedance to Xiaohongshu and Bilibili, many of China’s most innovative companies move beyond horizontal product offerings or traditional service goals. Instead, they think vertically and break out of the box—evolving into entire ecosystems of their own. (Fun fact: the entrepreneurs behind these companies were all born in the 1980s, between 1983 and 1989).

In that sense, state media like People’s Daily calling Labubu “a benchmark of China’s pop culture” isn’t off the mark.

Still, some marketing critics argue there’s room for more ‘Chineseness’ in Labubu and POP MART’s brand-building strategies—particularly through collections inspired by Chinese heritage, which could further promote national culture on the global stage (Wang 2023).

Meanwhile, Chinese official channels have already begun positioning Labubu as a cultural ambassador. In the summer of 2024, a life-sized Labubu doll embarked on a four-day tour of Thailand to celebrate the 50th anniversary of China–Thailand diplomatic relations.

The life-sized mascot of a popular Chinese toy character, Labubu, visited Bangkok landmarks and was named “Amazing Thailand Experience Explorer” to boost Chinese tourism. Photo Credit: Facebook/Pop Mart, via TrvelWeekly Asia.

In the future, Labubu, just like Hello Kitty in Japan, is likely to become the face of more campaigns promoting tourism and cross-cultural exchange.

Whatever happens next, it’s undeniable that Labubu stands at the forefront of a breakthrough moment for Chinese designer toys in the global market, and, from that position, serves as a unique ambassador for a new wave of Chinese creative exports that resonate with international audiences.

For now, most Labubu fans, however, don’t care about all of that – they are still on the hunt for the next little monster, and that’s enough to keep the Labubu hype burning.🔥

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References (other sources included in hyperlinks)

• Du, Daisy Yan. 2019. Animated Encounters: Transnational Movements of Chinese Animation, 1940-1970s. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

• Ge, Tongyu. 2024. “The Role of Emotional Value of Goods in Guiding Consumer Behaviour: A Case Study Based on Pop Mart.” Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Education Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries. DOI: 10.54254/2753-7048/54/20241623.

• Liu, Enyong. 2025. “Analysis of Marketing Strategies of POP MART,” Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Financial Technology and Business Analysis DOI: 10.54254/2754-1169/149/2024.

• Wang, Zitao. 2023. “A Case Study of POP MART Marketing Strategy.” Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Management Research and Economic Development. DOI: 10.54254/2754-1169/20/

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Lured with “Free Trip”: 8 Taiwanese Tourists Trafficked to Myanmar Scam Centers

10 Viral Chinese Phrases You Didn’t Know Came From Video Games

Earring Gate: Huang Yangdiantian and the 2.3 Million RMB Emerald Earrings

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

Squat or Sit? China’s Great Toilet Debate and the Problem of Footprints on the Seat

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Media12 months ago

China Media12 months agoA Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

-

China Society9 months ago

China Society9 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoThe “City bu City” (City不City) Meme Takes Chinese Internet by Storm

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media