China Society

Chinese Netizens Voice Concerns over Molly the Elephant, Call for Animal Performance Boycott

Molly the elephant has become a powerful symbol for hundreds of other performing elephants in China.

Published

4 years agoon

The fate of Molly, an elephant born in the Kunming Zoo and separated from its mother at the age of 2, has become a topic of public debate in China. As viral photos show the elephant being forced to perform tricks, calls for an animal performance ban in China are growing louder.

A little elephant named Molly is a big topic of discussion on Chinese social media this week. There are various hashtags about Molly on Weibo, where the elephant also has several fan forums (‘supertopics’) dedicated to her.

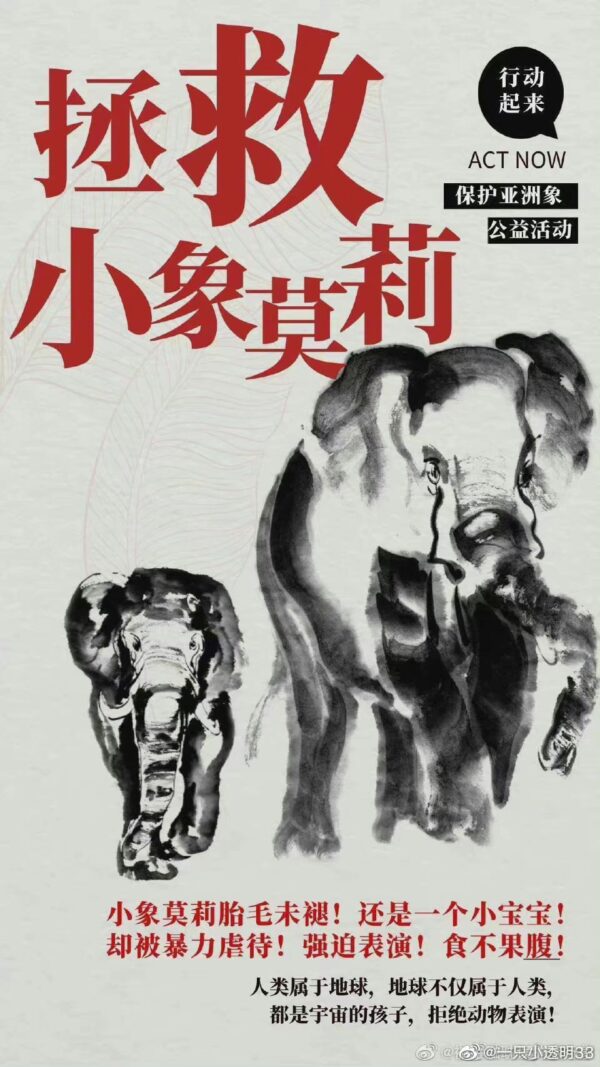

There are Molly artworks, Molly videos, Molly gifs, Molly cartoons, but most of all, there are the calls from netizens to ‘rescue Molly the little elephant’ (#救救小象莫莉#).

Molly’s Chinese name is Mòlì (莫莉), an Asian elephant born on March 20 in 2016 in the Kunming Zoo in Yunnan. The baby elephant was initially nicknamed “Little Princess” (小公主). When she turned one year old, the Kunming Zoo invited the public to help come up with a name for her.

On her first birthday, the popular ‘Little Princess’ received her official name and a special big elephant birthday cake. The celebration was covered by local media at the time.

Although Kunming Zoo initially seemed to take pride in their baby Molly, they separated her from her mother at the age of two in April of 2018. Molly was then transferred from Kunming Zoo to Qinyang, Jiaozuo, in Henan in exchange for another elephant.

Over the past few years, Molly the elephant has allegedly been trained to do tricks and performances and to carry around tourists on her back at the Qinyang Swan Lake Ecological Garden (沁阳天鹅湖生态园), the Qinyang Hesheng Forest Zoo (沁阳和生森林动物园), the Jiaozuo Forestry Zoo (焦作森林动物园), and the Zhoukou Safari Park (周口野生动物世界).

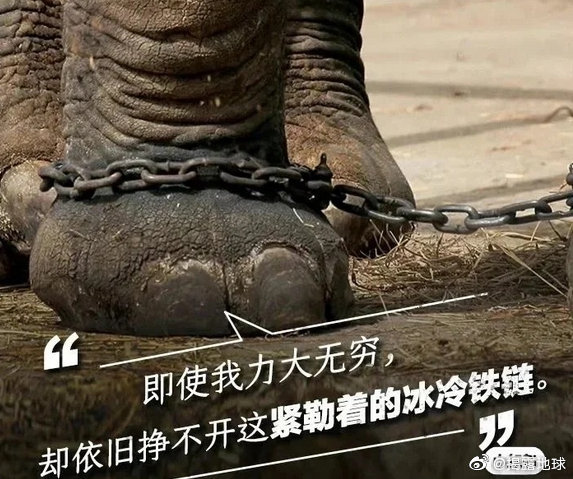

Netizens started raising the alarm about Molly’s welfare when they spotted her chained up and seemingly unhappy, forced to do handstands or play harmonica, with Molly’s handlers using iron hooks to coerce her into performing.

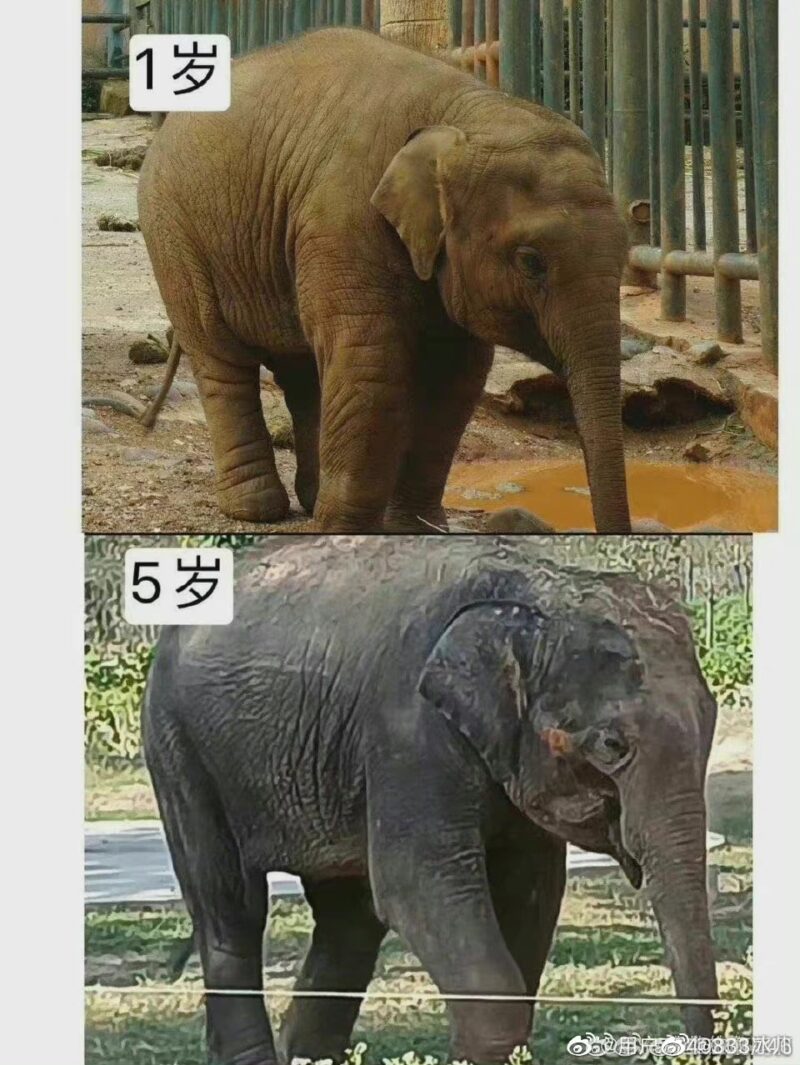

Posts about Molly being abused started to gain more online attention in the summer of 2021, and photos showing the stark difference between Molly at the age of one and at the age of five years old circulated online.

After so many netizens expressed concerns about the elephant’s mistreatment, the local zoo and authorities issued a statement in September of 2021 saying Molly was not being maltreated. But because no further clarification was given, netizens kept pushing for the elephant to be rescued and reunited with its mother in Kunming.

One of the reasons why Molly became a big topic on social media again this week is because her case was pushed forward on the social media platform Xiaohongshu, after which it also gained renewed attention on Weibo due to various big accounts posting about ‘Save Molly’ and calling for an elephant performance ban in China.

One of these influentiual people expressing concerns over the elephant is Taiwanese actress Chen Qiao’en (陈乔恩), who posted about Molly on Weibo on April 24, using the #SaveMollytheElephant hashtag:

“It’s heartbreaking to see Molly covered in wounds. She shouldn’t be treated like this. Please reject animal performances, please don’t abuse animals, please save Molly the elephant.”

Chen’s post received over 90,000 likes and a lot of attention, leading to more netizens voicing their concerns about the elephant and joining online groups about Molly’s case.

As voices speaking up for Molly grew louder, some of the groups and hashtags related to the ‘Save Molly’ movement were taken offline by Weibo censors.

“There are many ‘Molly’s’ in this world, the more you try to silence us, the louder we will get,” one Weibo commenter wrote.

A Maze of Conflicting Regulations

Beyond Molly’s situation, there is a somewhat confusing web of laws, regulations, and standards about wildlife protection and animal performances in China.

China’s Wildlife Protection Law (WPL), the national legislation for animal protection, was enacted in 1989. Throughout the decades, the law was widely criticized for not doing enough to actually protect animals and promoting the use of wildlife for human benefit. Although the law was revised in 2015, it still facilitated the commercial use of wildlife and there is no anti-cruelty legislation that might penalize cruelty to animals in zoos, wildlife parks, or other venues where wild animals are kept in captivity (Li 2021, p. 227).

When it comes to China’s zoos and safari parks, there are two regulatory bodies that play an important role: China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (住房城乡建设部, MHURD), and the Chinese State Forestry and Grassland Administration (国家林业和草原局, SFGA).

The Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MHURD) is the relevant organ overseeing Chinese zoos, which are usually owned and managed by municipal or regional governments. The MHURD also hosts the Chinese Association of Zoological Gardens (中国动物园协会, CAZG), which is an organization that most of China’s larger zoos are members of.

China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development banned animal performances in China over a decade ago in 2011, although the rule excluded performances at aquariums and did not specify penalties (China Daily 2012). In 2013, the MHURD also issued the “National Zoo Development Outline” (“全国动物园发展纲要“) which strictly prohibited all animal performances in zoos.

Nevertheless, many zoos and wildlife parks have still continued shows featuring cycling bears, jumping tigers, and dancing elephants since then – and not necessarily illegally.

One of the reasons why there are conflicting regulatory regimes is because “zoos” and “wild animal parks” fall under different jurisdictions in China.

The MHURD 2011 administrative national ban on animal performance was unable to stop animal performances at China’s privately-owned wild animal parks, safari parks, or circuses, since they are administered by the Chinese State Forestry and Grassland Administration (SFGA), which also regulates the holding of all exotic species, including those in city zoos. The SFGA, however, does not consider the welfare of these animals its responsibility (see Arcus Foundation 2021, p. 99; Li 2021, p. 227).

City zoos can theoretically still subcontract animal performances to private companies within special areas of the zoo as long as their contract was signed before 2011, and can also still sell or trade animals with these parks. Dozens of zoos with performance programs have therefore continued animal performances, sometimes also in violation of policies in place (Arcus Foundation 2021, p. 99; Li 2021, p. 19).

In line with the WPL, the SFGA is able to provide permits that allow animal parks to hold animal “exhibition and performances.” The Qinyang Swan Lake Ecological Garden, where Molly is, also has a permit to “showcase wildlife” (展演野生动物), basically giving them a green light to put on performances.

Beyond Molly

On April 27, the Kunming Zoo responded to the online storm over Molly, claiming that the elephant is in good condition and that the zoo in question has since long stopped animal performances.

Chinese media outlet Phoenix News also published an article about Molly on April 30, aimed to uncover the truth about the conditions in which Molly is currently being kept at the Qinyang Hesheng Forest Zoo.

The report concluded that Molly was kept in good living conditions, and that the elephants at the park were not participating in any (circus) performances. The person in charge of the Qinyang Hesheng Forest Zoo, Shi Baodong (史保东) reportedly claims the park has stopped all animal performance activities as of April 2019, with Shi denying all claims of animal abuse taking place.

Staff members also said that some of the footage and images circulating online in relation to the Molly incident are not of Molly at all, instead showing elephant training in Thailand, India and other countries.

But many Chinese netizens believe the zoo is not speaking the truth, since social media users said they still saw Molly performing and carrying zoo visitors on her back in 2021. Even if Molly is not performing at this moment, many still think that media reports and statements cover up the truth of how the elephant is really doing.

For others, the ‘Save Molly’ hashtag is not just about Molly anymore, as the elephant has come to represent hundreds of other elephants who are living in captivity in China and are forced to perform. They hope the government can prohibit elephant performances entirely and introduce better laws and regulations to prohibit animal performances and mistreatment.

“One person doesn’t have a lot of power, but as a group we have more power,” the description for one Molly supertopic on Weibo says (小吉象莫莉).

Underneath one of the Weibo threads about Molly’s current situation, a top commenter replies: “This is not just about Molly anymore, we want to protect all of the ‘Molly’s’ out there.”

“Reject animal performances, don’t turn suffering into entertainment.”

This is not the first time netizens come into action to get justice for zoo animals that are suffering. In 2017, visitor photos of a mouth-foaming, lethargic-looking panda at Lanzhou Zoo also caused outrage on Weibo. In 2016, netizens also jumped to the aid of a polar bear by the name of Pizza after he was found living in deplorable conditions at an aquarium in the Grandview Mall in Guangzhou. He was later removed from the mall.

UPDATE MAY 17 2022: MOLLY RETURNS TO KUNMING ZOO

To follow more updates regarding Molly, check out Twitter user ‘Diving Paddler’ here. We thank them for their contributions to this article.

To read more about zoos and wildlife parks causing online commotion in China, check our articles here.

By Manya Koetse

References (other sources linked to within text)

Arcus Foundation (Ed.). 2021. State of the Apes: Killing, Capture, Trade and Ape Conservation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

China Daily. 2012. “Animal Rights Groups Seek Performance Ban.” China Daily, April 16 http://www.china.org.cn/environment/2012-04/16/content_25152066.htm [Accessed May 1 2022].

Li, Peter J. 2021. Animal Welfare in China: Culture, Politics and Crisis. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our weekly newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Society

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

From 5,000 people crashing a rural pig feast in Chongqing to the collective effort to save Yanran Angel hospital.

Published

1 month agoon

January 22, 2026

🔥 China Trend Watch (1.22.26)

Part of Eye on Digital China by Manya Koetse, China Trend Watch is an overview of what’s trending and being discussed on Chinese social media. The previous newsletter was a deep dive into the Dead Yet? app phenomenon. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Not a day goes by these days when Trump isn’t trending. Whether it’s about Venezuela and Greenland, ICE, or his recent speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, his name keeps popping up in the hot lists.

However, there are dozens of other topics being discussed on Chinese social media that actually aren’t about the US or the shifting geopolitical landscape. From football to pig-slaughter feasts, from a Henan grandpa in Paris to the latest birth rates, there is an entire world of topics out there that’s blissfully unconnected to anything happening in Washington or Davos — with many of these discussions signaling bigger social stories unfolding in China today. Let’s dive in.

Quick Scroll

- 🐶 “Eat more dog meat,” a local Community Health Service Center in Ya’an advised in a seasonal health text, suggesting it would help people stay healthy & warm during cold weather. The message sparked controversy among dog lovers online. The center later apologized and issued a corrected version, replacing dog meat with lamb, beef, and chestnuts.

- ⚽ Chinese goalkeeper Li Hao (李昊) is the man of the moment after China’s under-23 national football team beat Vietnam (0-3) and advanced to the final of the AFC U23 Asian Cup. It marks the first time since 2004 that any Chinese men’s national team (at any level) has reached the final of a continental tournament. In the final, China will face Japan.

- 👶 China’s latest birth data for 2025 are in, showing yet another record low. The birth rate fell to 5.63 per 1,000 people, with 7.92 million babies born last year — a 17% year-on-year decline.

- 💸 An “underground” private tutoring operation in Beijing has been hit with a staggering fine of more than 67 million yuan (US$9.6 million) for offering after-school classes without official approval. It’s the highest fine so far under China’s “Double Reduction” policy, introduced in 2021 to curb private tutoring and ease academic pressure on students.

- 🕯️ He Jiaolong (贺娇龙), a Xinjiang local official who was at the forefront of Chinese officials livestreaming & promoting their regions in creative online ways, died this week after a fatal fall from a horse during work-related filming. She was 47 years old.

- 🎭 Another death that trended this week was that of renowned Chinese comedian Yang Zhenhua (杨振华, b. 1936), a crosstalk (相声) artist remembered for his classic performances and widely regarded as a cultural icon.

- 🏛️ A child abuse case that has haunted Chinese netizens for the past two years has come to a close. Xu Jinhua (许金花), the stepmother who tortured and starved her 12-year-old stepdaughter, known as “Qiqi,” to death, was executed on January 20. Xu was sentenced to death in April 2025, and her appeal was rejected last November.

What Really Stood Out This Week

1. Mass Shutdowns of Local Chinese Pig-Slaughter Feasts

Annual pig feasts are traditionally meant to be a source of community bonding and ritual exchange. But for many towns and districts, páozhūyàn (刨猪宴), traditional pig-slaughter feasts, have now become a source of concern, leading to shutdowns of local events across multiple provinces.

The story begins on January 9, when a farmer’s daughter nicknamed Daidai (呆呆) from Hezhou in Chongqing posted a lighthearted message on Douyin asking whether people could help with her family’s pig slaughter, saying her old dad would not be able to hold down the two pigs. In return, she promised to treat helpers to “pork soup and rice,” adding: “To be honest, I just want the road in front of my house to be packed with cars, even more than at a wedding. I want to finally prove myself in the village!”

Two days later, on January 11, when the pig feast took place, Daidai got more than she had asked for. Not only was the road in front of her home packed with cars — the entire village was completely blocked as over 1,000 cars and some 5,000 visitors arrived. With two pigs nowhere near enough, five pigs ended up being slaughtered. Livestreamers flooded the scene, Daidai’s name was quickly trademarked, and before she knew it, she had entered internet history — including her own Baidu page — as the girl who turned a local gathering into a national feast.

Daidai (middle) hadn’t expected her call for help with slaughtering two pigs would end up in 5000 people coming to her town.

By now, the incident has spiraled into a much bigger issue, as others in the Sichuan–Chongqing region want to replicate the viral success of Hechuan, creating chaos and sometimes unsafe situations by turning neighborhood moments into tourist activities. This has led to a series of events being canceled or shut down.

On January 14, a planned páozhūyàn, initiated by local influencer Jia Laolian (假老练) in Longquanyi District in Chengdu, had to be canceled at the last minute after thousands of people registered to attend. On January 17, an online influencer in Caijiagang Subdistrict, Chongqing, also held a free pig-slaughter feast that quickly led to potentially dangerous overcrowding. Police shut it down. Another event took place in Ziyang, where 8,000 people had registered to attend while there were only 200 parking spaces available. There were more.

The current hype surrounding these pig-slaughter events reflects a sense of urban–rural nostalgia for local traditions and human connections, but probably says more about how viral tourism in China has worked since the frenzy surrounding Zibo: at lightning speed, influencers and local tourism bureaus jump onto fast-moving trends, hoping to get their own viral moment and, quite literally, piggyback on it.

While these moments can create a moment of hype, the downsides are clear: a lack of oversight, weak crowd management, intrusion to local communities, and lives being suddenly disrupted. For now, ‘Daidai’ has gained about two million users on her social media account. She says she hopes to do “something meaningful” with her online influence and has become an organic ambassador for Hechuan. At the same time, she also wants some calm after the storm, saying:“The Zhaozhu Yan in Heichuan has concluded successfully. I hope everyone can return to their normal lives. I also hope my parents can go back to their previous life—I don’t want them dragged into the internet world.”

2. How a Hospital Crisis Won China’s Trust

Usually, when news emerges about Chinese celebrities facing debts or court papers, it signals a serious blow to their reputation. But in a case that trended over the past week involving Chinese actor/businessman Li Yapeng (李亚鹏) and singer/pop icon Faye Wong (Wang Fei 王菲), the opposite is true.

Li and Wong were previously married and are parents to a daughter born with a cleft lip and palate. Their experiences in getting treatment and surgery for their daughter led them to become deeply involved with the efforts to help other children. In 2006, they founded the Yanran Angel Foundation (嫣然天使基金). A few years later, they established the Yanran Angel Children’s Hospital (嫣然天使儿童医院), China’s first privately-operated non-profit children’s hospital, providing surgeries, orthodontics, speech therapy, and other support to thousands of children—many of them at no cost for underprivileged families.

For the first ten years that Li and his team leased the hospital location, the landlord provided them with heavily discounted rent as a sign of his goodwill. In 2019, that agreement ended, and the rent doubled to market value at 11 million yuan per year (over US$1.5 million). But then Covid hit, and while the hospital still had all of its staffing and lease costs, surgeries were postponed.

On January 14 this year, Li Yapeng posted a lengthy video on his Douyin account titled “The Final Confrontation” (最后的面对), in which he explains how they fell behind on their rent since 2022, now finding themselves in a debt of 26 million yuan (over US$1.5 million) and facing a court judgement that leaves them with little choice but to vacate the premises and shut the hospital down.

Something that struck a chord with netizens is how Li, who bears joint liability for the unpaid rent, made no excuses and openly acknowledged his legal obligations, while at the same time emphasizing his personal sense of responsibility to ensure that children waiting for surgery would still receive the help that had been promised to them.

Public perception of Li Yapeng, who was previously seen as a failed businessman, transformed overnight. He was suddenly hailed as a hero who had quietly devoted himself to charity all this time, while accumulating personal debts.

Donations started flooding in. Within two days, over 180,000 people had donated a total of 9 million yuan (US$1.3 million), and by January 19 this had grown to more than 310,000 people supporting the hospital with nearly 20 million yuan (US$2.8 million). Beyond direct donations, netizens also supported Li Yapeng by tuning into his e-commerce livestreams. One businessman from Jiangsu even offered 30,000 square meters of free space for the hospital to relocate.

Meanwhile, netizens began wondering why Faye Wong, Li’s ex-wife with whom he had founded the foundation and hospital, was staying quiet. Just as some started to label her a diva who no longer cared about the cause, a 2023 audit report revealed that since divorcing Li Yapeng in 2013, she had been anonymously donating to the fund every year for a decade, totaling more than 32.6 million yuan (US$4.6 million) to cover rent and staff salaries.

There are many aspects to this story that have caused it to go viral, and that make it particularly noteworthy. It is not just the turnaround in public sentiment regarding Li and Faye Wong, but also the fact that people are more willing to donate to a cause they genuinely believe in. Although Li and Wong’s foundation technically falls under the Red Cross system, that organization has faced significant criticism and public distrust in China over the years.

What also helps are the personal stories shared on social media by those who have had direct experience with the hospital, or who know people working there. These include deeply moving accounts from families who saw all their savings depleted while trying to get proper care for their three-year-old child born with a cleft lip, then traveling for days from Gansu to Beijing with little more than a sliver of hope—only to learn that their child would not only receive surgery for free, but that the hospital would also help cover temporary lodging and travel costs. Many feel that causes like this are rare, and deserve to continue.

After years of stories about celebrities evading taxes, good causes misspending money, and corruption getting mixed up with charity, this is a story that restores trust — showing that some celebrities truly care, that some charities do turn every penny into help for those in need, and that netizens can genuinely make a difference. “This is the most heartwarming news at the start of the year,” one Weibo commenter wrote.

For now, it remains unclear whether the hospital can remain at its current location, but operations continue, and negotiations are ongoing. Fundraising has been paused for the time being, as annual donation targets have already been exceeded.

3. The Sudden Death of a 32-Year-Old Programmer and the Renewed Debate Over China’s Tech Overtime Culture

The sudden death of a 32-year-old programmer who worked at a tech company in Guangzhou is sparking discussion these days, as his death is being linked to the extreme overtime work culture in China’s tech sector.

The story is attracting online attention mainly because his wife, using the nickname “Widow” (遗孀), has been documenting her grieving journey on social media, sharing stories about how she misses her late husband and the things she wishes had gone differently. He was always working late, and she often asked him to come home when he still hadn’t returned by 10:00, 11:00 p.m., or even midnight.

Gao Guanghui (高广辉) worked as a software engineer and department manager. Despite his “seriously overloaded” working schedule, his now-widowed wife describes their life together as “very happy.”

On Saturday, November 29, 2025, the day of his passing, Gao mentioned that although he was feeling unwell, he still had work matters with approaching deadlines to handle. Browser records show that he accessed the company’s internal system at least five times that morning before fainting and experiencing sudden urinary incontinence.

While preparing to go to the hospital, Gao reportedly urged his wife to bring his laptop with them so that he could finish his tasks. However, he collapsed before the two had even gotten into the car. Despite an ambulance arriving at 9:14 a.m. and efforts to save him, he passed away two hours later. He died of cardiac arrest, and hospital records note his high-pressure, long-hour work schedule.

Even in the final moments of his life, work continued to intrude. Gao was added to a work WeChat group at 10:48 a.m., while hospital staff were still attempting to resuscitate him. Hours after his death was declared, colleagues continued to send him work messages, including one at 9:09 p.m. asking him to urgently fix an issue.

Making matters worse, Gao’s widow says that in the second week after his death, his company had already processed his resignation and disposed of his belongings. The items that were sent to her were crushed and poorly packed. To this day, she says she has received no apology, no compensation, no replacement items, and none of her husband’s missing belongings.

Visuals dedicated to Gao, shared on Xiaohongshu.

On social media, people are angry. Reading about Gao’s life story — and how he was always a hard worker, sometimes working two jobs at a time — many comments indicate that it is often the most dedicated ones who get pressured the most. They see him as a victim of tech companies like CVTE that go against official guidelines and perpetuate a work culture where working overtime becomes the norm, only leading to more workload.

This is not the first time such a story has gone viral. In 2021, the death of an employee who worked at Pinduoduo triggered similar discussions about strenuous “996” schedules (working 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days per week).

Similar deaths include the 2011 case of 25-year-old PwC auditor Pan Jie, whose story went viral on Sina Weibo after doctors concluded that overwork may have played a crucial role in her death. Likewise, the at-desk death of a 24-year-old Ogilvy employee in Beijing and the 2016 death of Jin Bo, deputy editor-in-chief of one of China’s leading online forums, also prompted calls for greater public awareness of the risks of overwork — especially among young professionals.

On the Feed

“Paris Without the Filter”

“Filter-Free Paris,” or “Paris without a filter” (素颜巴黎), unexpectedly went viral after a grandpa from China’s Henan province, traveling with a senior tour group, shared his unfiltered and casual photos of rainy Paris. In an age when European travel photos are often heavily filtered and glamorized on Chinese social media, many found the grandpa’s grey, plain images of the “City of Romance” not only amusing but also refreshingly honest.

Seen Elsewhere

• A Chinese state media editorial framed the Greenland dispute as a “wake-up call” for Europe to reduce its reliance on the US. (CHINA DAILY)

• Why Western “Chinamaxxing” and “very Chinese time” memes say more about a “decay of the American dream” than about China itself. (WIRED)

• WIRED seems to be at a “very Chinese time” itself, and also launched its China issue, introducing 23 ways you’re already living in the ‘Chinese Century.’ (WIRED)

Title/Image via Wired, Andria Lo

• As Trump sows division, China says it’s the calm, dependable leader the world needs. (CNN)

• Nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution has become one of the few legally viable means of resistance, according to Shijie Wang. (CHINATALK)

That’s a wrap! Thanks for reading.

If you happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

See you next edition!

— Manya

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo. Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. If you no longer wish to receive these newsletters, or are receiving duplicate editions, you can unsubscribe at any time.

Chapter Dive

Why Were 100,000 Pregnant Women’s Blood Samples Smuggled Out of China?

How and why fetal sex testing became a national security story

Published

2 months agoon

December 25, 2025

A noteworthy story in Chinese media recently, which also made it to the top trending lists on Kuaishou and Weibo, concerns the uncovering of a widespread criminal network that smuggled blood samples from over 100,000 pregnant women across the border, exposing a black-market chain active across all provinces of China. In this deeper dive, I look at what received far less attention: why so many pregnant women were willing to provide their blood in the first place.

The case was part of a major operation by Guangzhou’s anti-smuggling authorities following a year-long investigation and the mobilization of 265 officers. As part of the operation, two professional criminal groups specializing in the smuggling of pregnant women’s blood samples were dismantled, and a total of 26 people were arrested.

The groups earned a staggering 30 million yuan (US$4.2 million) from their blood-smuggling activities.

So far, the story reads almost like a vampire novel, especially with Chinese media detailing how the blood was smuggled: smugglers reportedly strapped tubes of blood to their bodies to cross the border. Others hid them in specially modified suitcases with concealed compartments.

Some commenters framed the story as the smuggling of “life samples carrying the genetic code of Chinese citizens,” and as the “poaching of ethnic genetic resources,” arguing that the data security implications could be serious if the blood were to be used for research by those with ulterior motives.

Other netizens suggested that “insiders within medical institutions must be involved,” possibly even through broader “cross-border project collaborations.” These suspicions were fueled by official reporting. Overall, the online media discourse surrounding the case focused on the risks these practices pose to national biosecurity, with fears that foreign entities could appropriate China’s human genetic information.

In reality, however, this story is about the widespread demand in China for prenatal blood testing for fetal sex determination.

The groups uncovered by Guangzhou authorities received blood from some 100,000 pregnant women because the women provided it themselves. The groups (illegally) advertised on social media that they offered non-invasive fetal sex identification and genetic disease screening, with clients paying fees of 2,000–3,000 yuan (US$285–US$426) for these blood tests.

According to Guancha.cn, the blood would be drawn by “acquaintances” or through online medical platforms, after which the samples would be mailed by courier to a designated address, where they were collected, concealed by smugglers, and delivered to overseas laboratories for testing.

Smuggled blood as seen in CCTV feature

Although none of the Chinese news reports on this case disclose where these “overseas labs” are actually located, the reports mention cooperation between authorities in Guangzhou, Foshan, and Shenzhen, and the details provided make it highly probable that the case concerns the mainland–Hong Kong border.

In a recent CCTV feature on the news, Zheng Zhong (郑重), Deputy Director of the Investigation Division of the Guangzhou Customs Anti-Smuggling Bureau, said:

“China has explicitly prohibited the determination of fetal sex for non-medical needs, which is a protection of the fetus’s right to life. It is also to maintain a healthy population ratio. Blood sample smuggling poses a high potential risk to public interests and national biosecurity.”

Fetal sex determination has been illegal in China since the first regulation in 1989, with later laws specifically outlawing the use of ultrasound imaging or other techniques to identify fetal sex.

Why Fetal Sex Determination Still Matters

Why did Zheng mention the prohibition of fetal sex determination tests in China to “maintain a healthy population ratio”?

Although abortion has generally been permitted in China—which has one of the most lenient abortion regimes in the world—strict controls on sex-selective abortions have been in place since the early 1990s.

One of the unintended effects of China’s one-child policy since 1979 has been the widespread occurrence of sex-selective pregnancy terminations, linked to traditional son preference. Fetal sex identification has been a precursor to these abortions, contributing to severe distortions in the country’s sex ratio. Non-medical fetal sex identification and sex-selective abortion came to be known as the “two illegitimates.”[1]

Now that China is entering its first decade since the end of the one-child policy, you might expect that these “two illegitimates” have become less pressing issues. After all, with couples now allowed to have more than one child (even three children or more), why would sex determination still be so relevant that 100,000 women would continue to submit blood samples despite the practice officially being illegal?

🔎 In reality, research suggests that the end of China’s one-child policy has not been the turning point it was perhaps expected to be. Although it has reduced pressures, its impact on son preference and sex-selective practices has been somewhat underwhelming.[2]

Since 2016, there has indeed been a rise in daughter preference and gender indifference, as well as a decline in male-to-female sex ratios at birth, but significant regional differences remain and son preference persists, alongside sex-selective abortion.[3] As a result, the sex ratio at birth remains skewed in certain provinces, especially for first births.[4]

👉 So what does this mean in practice? It means that, despite laws and regulations, expecting parents are still eager to find ways to identify fetal sex by whatever means possible (blood-based tests, ultrasound scans), and that agencies able to profit from this desire have been widespread for years.

In provinces like Jiangxi, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hubei, and Hunan, which together with Hainan accounted for more than a third of all births in China in 2020, there is still a deeply rooted familism culture and an abnormally high number of male births.[5]

Even though Chinese authorities introduced specific measures more than a decade ago to ban the mailing of blood samples overseas for fetal sex identification, underground networks smuggling fetal blood samples to Hong Kong for gender testing have been rampant—and this goes well beyond 100,000 samples.

Framing Pregnant Women’s Blood Smuggling in Chinese State Media

It is noteworthy that Chinese coverage of this case leaves out issues related to fetal sex selection, the persistence of sex-selective practices in post–one-child China, and parents’ willingness to learn the sex of their fetus to such an extent that they are prepared to pay large sums of money for this information.

In the 8-minute CCTV feature on this case, as well as in other reports, the core narrative centers on how an organized criminal network that endangered national biological security by illegally smuggling pregnant women’s blood samples was successfully dismantled by Chinese authorities through state surveillance and coordinated law enforcement.

China has, in fact, strict laws on the protection of human genetic resources. Since 2019, regulations have specifically prohibited foreign entities from collecting genetic material within China and restricted the transfer of genetic material and related data out of China. Any research involving Chinese human genetic resources must be conducted through approved collaboration with a qualified Chinese institution (see China Law Translate).

In the CCTV report, fetal sex identification is mentioned only briefly: first, in describing how the criminal group attracted customers online, and second, by Zhong, to emphasize that the practice is illegal. This framing places the entire issue within the domains of legality, regulation, and security, while the ethical, socio-cultural, and gender dimensions that lie at the root of the practice are entirely ignored.

Word cloud generated with the assistance of AI, based on the fully transcribed and translated text of the main CCTV investigative report on the blood-smuggling case.

Instead, the case is narrated using dominant language such as “blood smuggling,” “genetic resources,” and “security.” This framing has led to some confusion online. One of the most popular search queries related to the story on Weibo was: “What is the purpose of smuggling pregnant women’s blood samples abroad?” (孕妇血液样本走私境外目的是什么).

On Xiaohongshu, some commenters similarly asked: “I just don’t understand what pregnant women’s blood is used for.” Another user replied: “They can extract genetic codes, create a virus, and kill us with it.”

There are, however, many commenters who directly connect the case to its underlying issue. One woman on Xiaohongshu asked: “Isn’t it possible to tell [the fetus’s sex] just by doing a B-ultrasound? Why would they spend so much money to draw blood?” Another commenter replied: “It takes several months before you can do an ultrasound. A blood test is faster, and you can know the result before the abortion deadline.” (In some regions of China, non-medical abortions are not permitted after 14 weeks of pregnancy.)

Demographic Anxiety and Shifts in Narratives

Chinese headlines about the uncovering of the blood-smuggling operations appeared in the same week when netizens discussed unofficial reports about China’s 2025 estimated birth rates, suggesting that the country’s fertility rate will hit another historic low and fall to second-lowest in the world (higher only than South Korea), with a total fertility rate of about 1.09.

“Let people with money have kids,” some commenters suggested. “Right now, it’s hard for young people to get a job. When you can’t even find a job, who would think of having kids?”

Another person on Weibo wrote: “I’m part of the elite social class with a PhD degree, and yet I’m miserable. I’m pessimistic and disappointed about the future. I won’t have kids, won’t buy [a house], and won’t get married.”

Over the past years, and especially recently, Chinese authorities have introduced numerous measures in attempts to boost the country’s birth rates, from child-rearing subsidies to taxes on contraceptives.

In this light, tackling illegal practices involving fetal sex identification is more relevant than ever—and pushing such news to the top of China’s trending lists, together with frightening narratives about blood thieves and biosecurity risks, serves as a warning as much to smugglers as to expecting mothers not to engage in such practices. In this context, expecting parents would not only be crossing legal red lines by testing the sex of their unborn child, but would also be framed as handing over China’s national DNA to potential foreign enemies.

🔴 In doing so, Chinese official narratives shift, yet also fall back into old habits: at a time when fertility is dramatically dropping and confidence among young people in love & marriage is eroding, the state does more than regulate or guide ideas about family planning and fetal sex determination; it changes the meanings attached to it.

But there’s also a side effect to these stories. Because official news coverage presents the case as one of potential risks of Chinese genetic data being stolen, while largely leaving out the relevant social context, some ordinary Chinese netizens have begun to worry about what happens to their blood samples at hospitals once they leave their check-up appointments.

“Can they profit from it?” some wonder, while others worry about unintentionally contributing to future biological warfare.

Ultimately, the story of “blood smuggling” is not just about smugglers or overseas laboratories. It is about how, in an era of increasing demographic anxiety, reproductive behavior is increasingly reframed through the language of security.

Luckily, many genuinely don’t see what all the fuss is about: “People would really smuggle pregnant women’s blood abroad for what? Is it really so important to know whether you’re having a boy or a girl?”🔚

📌🎬 Although I also published last week, I didn’t send that article as a newsletter. So, in case you missed it, here’s a short recap: the past year has been a tumultuous one for China’s entertainment industry, and especially for renowned director Wong Kar-wai. After the success of the TV drama Shanghai Blossoms, a former screenwriter accused Wong and his team of discrediting, exploiting, and abusing him.

The case was already explosive, but it became even more sensitive when audio recordings were leaked in which Wong criticised the Party. Almost any other celebrity would likely have been blacklisted for such remarks, yet Wong seems to have escaped that fate. Why? You can explore the case in this in-depth article by Ruixin Zhang. It’s worth the read.

👉 This piece is part of Chapters, the format I use for deeper, more analytical pieces. Alongside Chapters, I also publish Signals, which tracks slower-moving shifts in Chinese online culture and digital life, and China Trend Watch, which offers a regular overview of what has been trending across China’s digital platforms. Keep an eye on the upcoming editions to follow the thread.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

[1] Ruby Lai Yuen Shan, “The Transformation of Abortion Law in China,” in Research Handbook on International Abortion Law, edited by Mary Ziegler (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023), 172–73.

[2] Xinyi Zhang, “Estimating the Effect on the Sex Ratio of the Two-Child Policy: Evidence from China,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies 9 (2023): 1–8.

[3] Li Mei and Quanbao Jiang, “Sex-Selective Abortions over the Past Four Decades in China,” Population Health Metrics 23, no. 6 (2025): 1–16.

[4] Mengjun Tang and Jiawei Hou, “Changes of Sex Ratio at Birth and Son Preferences in China: A Mixed Method Study,” China Population and Development Studies 8 (2024): 1–27.

[5] Tang and Hou, “Changes of Sex Ratio at Birth,” 4–5.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Spring Festival Trend Watch: Gala Highlights, Small-City Travel, and the Mazu Ritual Controversy

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West