China Media

Ministry of Education Bans the Idolization of China’s Top Gaokao Scorers

Stories of the top achievers of China’s national exams can no longer be propagated by state media; the emphasis should shift to the average, harmonious student.

Published

7 years agoon

The countdown has started for China’s national exams, the gaokao. Although the top scorers of these decisive exams are usually praised as champions, the Ministry of Education now warns against their idolization and orders schools and media to use ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ as their guide.

China’s Ministry of Education has issued an official announcement this week that it is no longer allowed to idolize the top scorers of China’s upcoming National Higher Education Entrance Examinations, usually abbreviated to gaokao (高考, ‘high exams’).

The notice was issued after a top-level conference on May 8, which focused on the enrollment process for China’s national graduation exams.

The gaokao will take place in June and always attract nationwide attention – both offline and online – in the weeks before they start. The exams are the most important moment of the year for those taking part; they are a prerequisite for entering China’s higher education institutions and are usually taken by students in their last year of senior high school.

“It is strictly prohibited to give publicity to gaokao top scorers.”

“It is strictly prohibited to give publicity to gaokao top scorers,” the head of the Ministry of Education, Chen Baosheng (陈宝生), was quoted saying by various state media outlets on Weibo, adding that “those who do so anyway will be dealt with accordingly.”

In the Ministry of Education’s announcement, it further said that education departments all over China should use Xi Jinping’s socialist ideology with Chinese characteristics as a guide to their work relating to the college national entrance exams this year.

The exams, that take place during a period of 2 days, are so important because scoring high grades for this exam can give high school students access to a better college, which enlarges their chances of obtaining a good job after graduation. Because the exam results are potentially life-changing, the gaokao period is generally a highly stressful time for students and their parents.

Those who succeed in becoming the number one scorers in their field and area, also known as the gāokǎo zhuàngyuán (高考状元, ‘gaokao champions’), are usually widely praised by Chinese media and educational institutions.

Year on year, the scores, names, photos, and stories of those students excelling in the humanities (文理状元) and science (理科状元) are publicized by national, provincial, and local newspapers.

Changing Propaganda: From Top Achievers to Harmonious Students

The announcement by the Chinese Ministry of Education to ban the promotion of the top scorers in the university entrance exams became a much-discussed topic on Chinese social media today.

In their report of the ban, Party newspaper People’s Daily published pictures showing how students and schools are preparing for the upcoming exams.

The photos are full of socialist-style propaganda-like slogans (e.g. “trials and hardships strengthen determination”), encouraging students to work and study hard and to repay their parents for the efforts they put into them.

Various pictures show how, to prepare for the decisive exams next month, students in Hengshui, Hebei, bring in meals for the class and then eat together from the same bowl in order to not waste valuable study time.

Instead of promoting and propagating the stories of China’s top scorers, Chinese state media now seem to shift their focus to students’ hard work and collaborate efforts to prepare for the exam.

In line with Xi Jinping’s socialist thought, which also promotes equality in education and the nurturing of “a new generation of capable young people who (..) are well-prepared to join the socialist cause”, the official focus has now apparently changed from top achievers to the average, harmonious and social student.

China’s higher education is extremely competitive, and so is the battle for the high gaokao scores; although as much as 9.75 million senior high school students are going to take part in the 2018 University Entrance Exams, only less than 100 of them will have the opportunity to become an actual gāokǎo zhuàngyuán or ‘top-score champion.’

Inequality behind the ‘zhuàngyuán’?

The gaokao top-score achievers are not just the minority when it comes to statistics, they are also the ‘elites’ of the supposed socialist society.

After claiming the title of 2017 Beijing University Entrance Exam top scorer, the 2017 zhuàngyuán Xiong Xuan’an was interviewed by Chinese media outlet The Paper and addressed some controversial issues on becoming one of the top scorers.

Xiong, during the interview, said that for students coming from rural areas, it is much harder to get into good universities, saying: “People like me are from middle-class families. We do not have to worry about food or clothes. Our parents are educated.”

He added: “We were born in large cities like Beijing. We simply got better education resources than the rest. Students from other places and rural areas are not able to get these benefits.”

“The top scorers nowadays are, generally speaking, coming from prestigious families.”

Over the past years, Chinese parents are increasingly spending huge amounts of money towards their children’s education, varying from extravagant summer programs to hiring ‘gaokao nannies‘ to support children taking the exams. Spending money on high-quality private schools and tutoring starts as early as kindergarten.

But not all families can afford top-notch schools for their children. Official statistics show that in 2017, dispensable income per capita in China is approximately 25,974 yuan (±US$4072).

Xiong told reporters that his parents are diplomats, saying: “It made my learning path easier. And the top scorers nowadays are, generally speaking, coming from prestigious families and are good at studying.”

Perhaps the general promotion of top-score achievers used to be an efficient way for state media to promote hard-working attitudes and the ‘Chinese dream‘, but the emergence of the more elite zhuàngyuán now has come to show how differences in educational resources have created inequality in educational opportunities.

Weibo Discussions

The recent ban on stories about the 2018 gaokao top scorers is an indication that the Chinese Ministry of Education now wants to de-emphasize worsening disparities within society, but not all commenters on Weibo agree with this shift.

“Why can’t we give publicity to the top scorers?”, author Tan Yantong (@谭延桐) asks on Weibo: “There is so much rotten entertainment news (..) and bullsh*t news, unbearable news, ruining our value system – why don’t you ban that sort of news?”

“What’s the use for me to become a number one scorer now?”

“Then you might as well ban the top scorers in sports,” others say: “That’s also highly competitive.”

“Now what’s the use for me to become a number one scorer anyway?” another commenter jokingly says.

But there are also supporters of the new guideline. “This is a good start,” one other Weibo user writes: “Elementary education is general education – not elite education. How to provide efficient and equal education is something the Ministry of Education needs to figure out through new strategies.”

By Chauncey Jung and Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Chauncey Jung is a China internet specialist who who previously worked for various Chinese internet companies in Beijing. Jung completed his BA and MA education in Canada (Univ. of Toronto & Queen's), and has a strong interest in Chinese trends, technology, economic developments and social issues.

China Arts & Entertainment

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

From China’s first soap opera Yearnings to the rise of AI-fueled nostalgia.

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 2, 2025

The year is 1990, and the streets of Beijing’s Fangshan District are eerily quiet. You can almost hear a pin drop in the petrochemical town, as tens of thousands of workers and their families huddle around their televisions, all tuned to the same channel for something groundbreaking: China’s very first soap opera, Yearnings (渴望 Kěwàng).

Yearnings tells the story of Liu Huifang (刘慧芳), a female factory worker from a traditional working-class family in Beijing, and her unlikely marriage to university graduate Wang Husheng (王沪生), who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Liu finds an abandoned baby girl, she adopts her and raises her as her own, against her husband’s wishes.

The couple is unaware that the foundling is actually the illegitimate child of Wang’s snobbish sister, Yaru. After Liu and Wang have a biological son, the marriage comes under further pressure, eventually leading to divorce. Liu is left as a single mother, raising two children on her own.

Still from Yearnings, via OurChinaStory.

Drawing inspiration from foreign dubbed television shows, Yearnings was produced as China’s first truly domestic, long-form indoor television drama. Spanning 50 episodes, the series traces a timeline from the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s through to the late 1980s—one of the most turbulent periods in modern Chinese history.

Before the series aired nationally on CCTV and achieved record viewership, the first station to air Yearnings in the Beijing region was the Yanshan Petrochemical TV Station (燕山石化电视台), China’s first major factory TV station (厂办电视台) located in Fangshan District.

Here, in this town of over 100,000, Yearnings garnered an astonishing and unprecedented 98% audience share. The series was truly groundbreaking and became a national sensation—not just because it was China’s first long-form television drama, or because it was a locally produced drama that challenged the long-standing monopoly of state broadcaster CCTV, but because Yearnings marked a major shift in television storytelling.

Until then, Chinese TV stories had always revolved around communist propaganda, or featured great heroes of the revolution. Yearnings, on the other hand, was devoid of political content and focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary people and their everyday struggles—love, desire, marital tension, single motherhood—topics that had never before been so openly portrayed on Chinese television.

The show’s creators had perfectly tapped into what was changing: the Communist Party was slowly withdrawing from private life, and people were beginning to see themselves less defined by their work unit and more by their home life—as consumers, as partners and parents, as citizens of a new China filled with aspirations for the future. Yearnings’ storyline was a reflection of that.

Chinese-Style “Nostalgia Core”

Yearnings marked a cultural turning point, coinciding with the rapid spread of TV sets in Chinese households. In 1992, economic reforms triggered a new era in which Chinese media became increasingly commercialized and thriving, before the arrival of the internet, social media, and AI tools once again changed everything.

Today, Yearnings still is a topic that often comes up in Chinese online media. On apps like Douyin, old scenes from Yearnings are reposted and receive thousands of shares.

📌 It’s emblematic of a broader trend in which more netizens are turning to “nostalgia-core.” In Chinese, this trend is known as “中式梦核” (Zhōngshì Mènghé), which literally means “Chinese-style dreamcore.”

Dreamcore is an internet aesthetic and visual style—popular in online communities like Tumblr and Reddit—that blends elements of nostalgia, surrealism, and subconscious imagery. Mixing retro images with fantasy, it evokes a sense of familiarity, yet often feels unsettling and deserted.

The Chinese-style dreamcore (中式梦核), which has become increasingly popular on platforms like Bilibili since 2023-2024, is different from its Western counterpart in how it incorporates distinctly Chinese elements and specifically evokes the childhood experiences of the millennial generation. Content tagged as “Chinese-style dreamcore” on Chinese social media is often also labeled with terms like “nostalgia” (怀旧), “childhood memories” (童年回忆), “when we were little” (小时候), and “Millennial Dream” (千禧梦).

According to the blogging account Yatong Local Life Observer (娅桐本地生活观察), the focus on the millennial childhood can be explained because the formative years of this generation coincided with a decade of rapid social change in China —leaving little in today’s modern cities that still evokes that era.

🌀 Of course, millennials in the West also frequently look back at their childhood and teenage years, particularly the 1980s and 1990s—a trend also embraced by Gen Z, who romanticize these years through media and fashion. In China, however, Gen Z is at the forefront of the “nostalgia-core” trend, reflecting on the 1990s and early 2000s as a distant, almost dreamlike past. This sense of distance is heightened by China’s staggering pace of transformation, modernization, and digitalization over the past decades, which has made even the recent past feel remote and irretrievable.

🌀 Another factor contributing to the trend is that China’s younger generations are caught in a rat race of academic and professional competition, often feeling overwhelmed by the fast pace of life and the weight of societal expectations. In this high-pressure environment—captured by the concept of “involution” (内卷)—young people develop various coping mechanisms, and digital escapism, including nostalgia-core, is one of them. It’s like a cyber-utopia (赛博乌托邦).

🌀 Due to the rise of AI tools available to the general public, Chinese-style nostalgia core has hit the mainstream because it’s now possible for all social media users to create their own nostalgic videos and images—bringing back the 1990s and early 2000s through AI-generated tools, either by making real videos appear more nostalgic or by creating entirely fictional videos or images that recreate scenes from those days.

So what are we seeing? There are images and videos of stickers kids used to love, visuals showing old classrooms, furniture, and children playing outside, accompanied by captions such as “we’re already so far apart from our childhood years” (example).

Images displayed in Chinese Dreamcore.

And notably, there are videos and images showing family and friends gathering around those old big TVs as a cultural, ritualized activity (see some examples here).

Stills from ‘nostalgia core’ videos.

These kinds of AI-generated videos depict a pre-mobile-era family life, where families and communities would gather around the TV—both inside and outside—from classrooms to family homes. The wind blows through the windows, neighbors crack sunflower seeds, and children play on the ground. Ironically, it’s AI that is bringing back the memories of a society that was not yet digitalized.

Nowadays, with dozens of short video apps, streaming platforms, and livestream culture fully mainstream in China—and AI algorithms personalizing feeds to the extreme—it sometimes feels like everyone’s on a different channel, quite literally.

In times like these, people long for an era when life seemed less complicated—when, instead of everyone staring at their own screens, families and neighbors gathered around one screen together.

There’s not just irony in the fact that it took AI for netizens to visualize their longing for a bygone era; there’s also a deeper irony in how Yearnings once represented a time when people were looking forward to the future—only to find that the future is now looking back, yearning for the days of Yearnings.

It seems we’re always looking back, reminiscing about the years behind us with a touch of nostalgia. We’re more digitalized than ever, yet somehow less connected. We yearn for a time when everyone was watching the same screen, at the same time, together, just like in 1990. Perhaps it’s time for another Yearnings.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Sources (other sources included in hyperlinks)

Koetse, Manya. 2016. “From Woman Warrior to Good Wife – Confucian Influences on the Portrayal of Women in China’s Television Drama.” In Stefania Travagnin (ed), Religion and Media in China. New York: Routledge.

Rofel, Lisa B. 1994. Yearnings: Televisual Love and Melodramatic Politics in Contemporary China. American Ethnologist 21(4):700-722.

Wang, Dan (汪丹). 2018. “《渴望》的艺术价值” [The Artistic Value of Yearnings].” Originally published in Beijing Daily (北京日报), October 12, 2018. Reprinted in Digest News (文摘报), October 20, 06 edition. Also see Sohu: 当年红遍大江南北的《渴望》.

Wang Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, a Chinese television soap opera with a message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Zhuge Kanwu. 2021. “重温1990《渴望》:苦得“刘慧芳”希望被导演写“死” [Revisiting 1990’s Yearnings: The Suffering Liu Huifang Hoped to Be Written Off by the Director]. Zhuge Dushu Wu (诸葛读书屋), January 22. https://wapbaike.baidu.com/tashuo/browse/content?id=b699ee532cf79f862bfa14ad.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

From historic speeches to trending slogans, this is China’s official media response to the US tariff escalation.

Published

3 months agoon

April 13, 2025

What do Mao’s 1953 Korean War speech and Yang Jiechi’s 2021 Alaska Summit remarks have to do with the escalating US–China trade war? In Chinese official media responses, history and emotionally charged rhetoric are used to clearly signal China’s stance and boost national confidence. Here, we explore three dominant narratives.

As you probably know by now, April 9 marked “D-Day” for Trump’s rollout of steep tariffs. On Chinese social media, the escalating trade war between China and the US dominated conversation, especially on that “D-Day Wednesday,” when nearly all of Weibo’s top 10 most-viewed hashtags were related to Trump’s tariffs and China’s retaliation.

Since developments are unfolding rapidly, here’s a quick recap:

- 🇺🇸💥 On Wednesday, April 2, President Trump announced steep new tariffs, including a universal 10% “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods, and an additional 34% reciprocal tariff specifically targeting China as part of the so-called “Liberation Day,” set to begin on April 9. Combined with pre-existing tariffs, this would bring the total tariff rate on Chinese goods entering the United States to over 54%.

- 🇨🇳⚔️On Friday, April 4, China’s State Council Customs Tariff Commission Office issued an announcement stating that, starting April 10, an additional 34% tariff would be levied on all imported goods originating from the United States, on top of existing tariff rates.

- 🇺🇸⚔️On Tuesday, April 8, Trump vowed to increase tariffs on Chinese exports by an additional 50% if Beijing would not withdraw its 34% counter-tariffs.

- 🇨🇳💥On Wednesday, April 9, China’s finance ministry announced it would further raise tariffs on US goods to 84% starting the following day, in retaliation for the newly imposed 104% tariff on Chinese goods.

- 🇺🇸💣On Wednesday, April 9, Trump then did a U-turn and halted the new steep tariffs for dozens of countries for 90 days, except for China, followed by yet another threat of an additional 21%, bringing those import taxes to 125%.

- 🇺🇸🚨On Thursday, April 10, it was clarified by the White House that tariffs on China would actually total 145%, combining the previously announced 125% with a 20% import tax levied for fentanyl smuggling.

- 🇨🇳💣On Friday, April 11, Chinese official channels reported that China would adjust its tariff measures on important goods from the US starting April 12, raising the rate from 84% to 125%. A related hashtag became no 1 trending topic on Weibo, where it received over 500 million views by Friday night (#对美所有进口商品加征125%关税#).

- 🇺🇸⬅️ On Friday, April 11, Trump’s administration announced that it will exempt smartphones, computers and some other electronic devices from the new tariffs, including the 125% levies imposed on Chinese imports (#特朗普政府再度退缩#; #美国免除智能手机电脑对等关税#).

There are hundreds of hashtags and trending topics circulating across Chinese platforms — from Weibo to Toutiao, from Kuaishou to Douyin — related to the latest developments in the US–China trade war. The topic is super popular, but censored comment sections and removed images also reveal just how sensitive it can be at times.

The biggest hashtags and slogans are those initiated and amplified by official channels. From press conferences to hashtags and visual propaganda, you can see a clear strategic media narrative that draws on history, national pride, and patriotism to frame recent developments, mobilize public sentiment domestically, and show China’s resilience to the rest of the world.

Here, I’ll highlight three hashtags that have recently become top trending, each representing a different kind of official narrative or rhetoric in response to the ongoing developments.

1. China Won’t Back Down

(China will see it through to the end #美方一意孤行中方必将奉陪到底#)

The message that China will not be intimidated by the US is one that echoes across Chinese social media these days, reinforced by official channels.

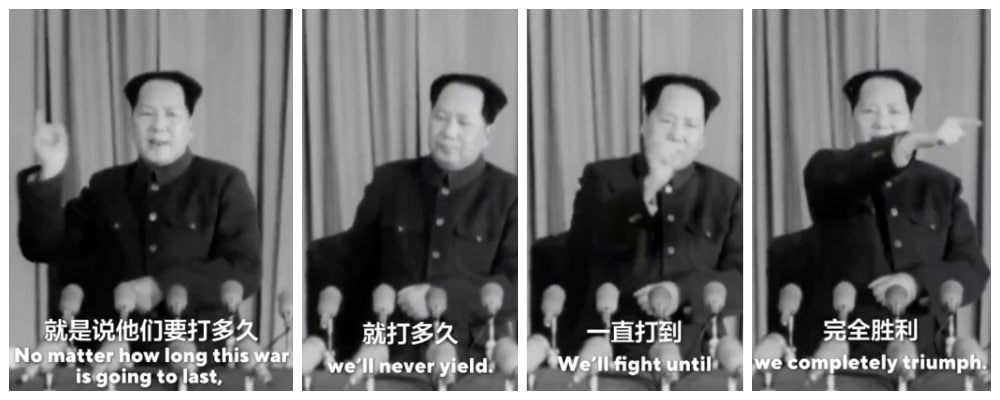

On April 9, the Weibo account of Chinese media outlet Guancha (@观察者网) and the state-run New Era China Foreign Affairs Think Tank (@新时代中国外交思想库) posted a video showing part of a speech given by Mao Zedong on February 7, 1953, during the final stages of the Korean War at the 4th Session of the 1st National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).

In the short fragment, Mao Zedong says:

🇨🇳📢 “As to how long this war will last, we are not the ones who can decide. It used to depend on President Truman, and it will depend on President Eisenhower, or whoever becomes the next US President. It’s up to them. No matter how long this war is going to last, we’ll never yield. We’ll fight until we completely triumph.”

The 1953 speech by Mao was also posted on the US social media platform X by Mao Ning (@毛宁), spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The video was then also spread by blogging accounts and regular netizens. History blogger Zijin Gongzi (@紫禁公子), who has over 435k fans on Weibo, reposted the video, writing:

💬 “Our forefathers never bowed their heads to strong enemies. How could we easily accept defeat? (..) We must not lose this spirit, we must let everyone know that we have a strong backbone and will never bow down.”

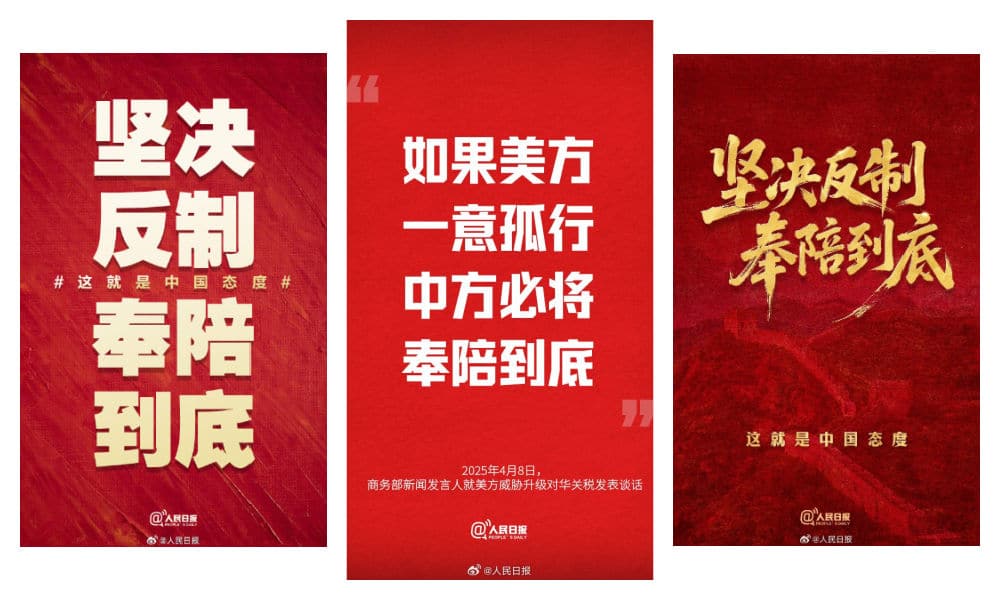

Together with the Mao video, the hashtag used by the Think Tank and many other Chinese media accounts, such as People’s Daily (@人民日报), is “If the US obstinately clings to its course, China will fight to the end [lit. accompany them to the end]” (#美方一意孤行中方必将奉陪到底#) and “fight to the end” (#我们奉陪到底#).

These phrases in part come from a press conference given by Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) on April 8. Here, he said:

🇨🇳📢 “I want to emphasize once again that there are no winners in trade wars and tariff wars, and protectionism is no way forward. The Chinese people do not provoke trouble, but they are also not afraid. Pressure, threats, and blackmail are not the proper ways to deal with China. China will inevitably take necessary measures and resolutely safeguard its legitimate rights and interests. If the American side disregards the interests of both countries and the international community and insists on waging a tariff war and trade war, China will fight to the end [lit. inevitably accompany them to the end 中方必将奉陪到底].”

The next day, these words had been turned into digital propaganda posters, with some slight variations in the phrases used. One People’s Daily graphic underlined: “We resolutely take countermeasures, and follow through until the end (坚决反制 奉陪到底),” accompanied by the line: “This is China’s attitude,” which was also turned into a hashtag (#这就是中国态度#).

2. This Is No Way to Deal with China

(Chinese people aren’t buying it #中国人从来不吃这一套#)

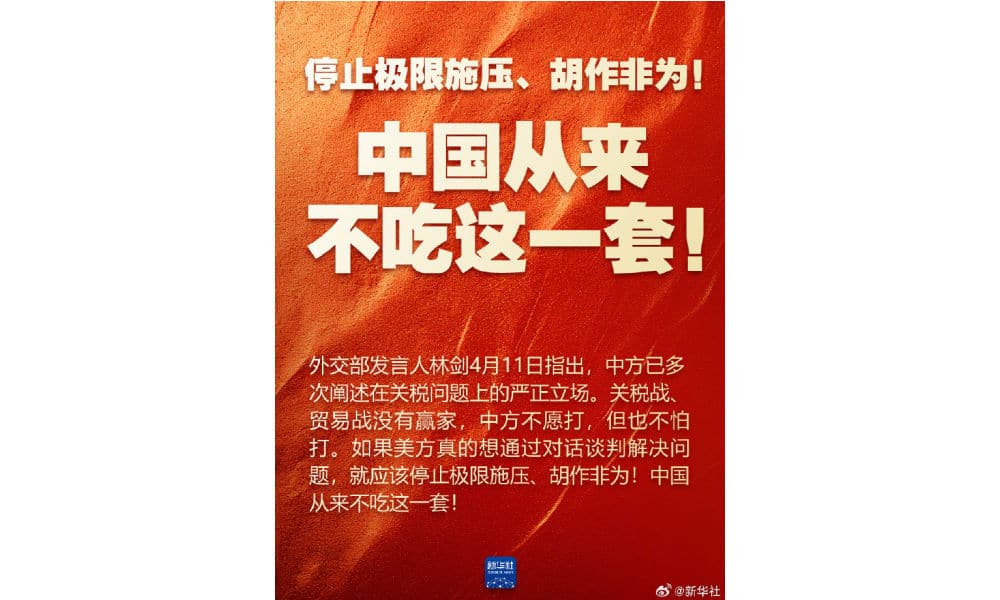

Another related yet somewhat different sentiment that dominates Chinese social media—led by official channels—is that China is not only rejecting the trade games played by the US, but is also distancing itself from the American playbook. The message is: this is no way to deal with China. This narrative, and the hashtag surrounding it, emerged slightly later than the first. While the earlier phrase about China not backing down trended as China matched the US in its tariff measures, this one took off with China’s final blow—raising the rate on US imports from 84% to 125% in response to the latest US tariff hikes.

The April 11 statement on the Ministry of Finance website (财政部网站), also posted on Weibo by Xinhua News (@新华社), announced that China would adjust its additional tariff measures on imports originating from the United States effective April 12. It also stated that China strongly condemns the US imposition of excessively high tariffs and will no longer engage in further tariff escalations:

🇨🇳📢 “Given that, at the current tariff level, US goods entering China effectively have no market viability, if the US continues to raise tariffs on Chinese exports to the US, China will no longer respond.”

The main hashtag used by Xinhua and many other media channels is “中国从来不吃这一套” (Zhōngguó cónglái bù chī zhè yī tào), which can be translated as: “The Chinese people have never accepted this,” or more colloquially, “We’re not buying it.”

The phrase initially became popular in 2021, after it was used by China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi (杨洁篪) during the first major strategic talks of the Biden administration, held in Anchorage on March 19. Due to the occasionally heated exchanges between the two delegations, some called the Alaska talks a “diplomatic clash.”

Yang Jiechi during the Alaska Summit

At the time, Yang delivered a lengthy statement to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, stressing that Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang are “inseparable parts of China,” and that China strongly opposes US interference in its internal affairs. Suggesting the US should focus more on its own human rights issues and racial problems instead of lecturing China, he added the now-famous line: “The US is not qualified to speak to China from a position of strength. The Chinese people don’t buy that” (美国没有资格居高临下同中国说话,中国人不吃这一套).

The phrase quickly went viral—boosted by state media, celebrated by netizens, and turned into a marketing slogan. It now appears on t-shirts, teacups, phone cases, and other patriotic merchandise.

The translation of the phrase still triggers discussions. While merchandise typically translates it as “Stop interfering in China’s internal affairs,” that’s not an accurate translation. During the Alaska Summit, interpreter Zhang Jing (张京) (who gained viral fame at the time) translated it in real-time as “This is not the way to deal with the Chinese people.” However, some commentators and professional translators argued this was a missed opportunity to take a tougher stance, as the Chinese phrase is much sharper and could be loosely translated as: “We Chinese people don’t swallow this crap.”

In Alaska, Yang emphasized that dealing with China requires mutual respect, and that history will prove that trying to strangle China’s rise would ultimately hurt the US itself (“与中国打交道,就要在相互尊重的基础上进行。历史会证明,对中国采取卡脖子的办法,最后受损的是自己。”)

Similar sentiments now dominate online media discourse in China. The slogan has evolved from “The Chinese people don’t buy this” (中国人不吃这一套) to the more authoritative “China has never bought this” (#中国从来不吃这一套#)

Adding fuel to this message are hashtags like “America’s repeated imposition of excessively high tariffs on China has become a joke” (#美方对华轮番加征畸高关税已沦为笑话#).

Ridiculing America (especially Trump) has become a popular pastime on Chinese social media this past week, with a flood of Chinese and international memes circulating widely.

Especially popular are memes mocking the idea of America as a future “Made-in-America” manufacturing hub, the irony of iconic American products (like MAGA hats) being made in China, and how everyday essentials such as eggs have reached historic price highs in the US (a crisis partly caused by bird flu but now worsened by the tariffs).

On April 13, the hashtag “The 145% tariff makes one panda plush toy cost 80 dollars” (#145%关税让1只熊猫玩偶卖80美元#) also went trending, sparking jokes about how even the most trivial things could suddenly become luxuries in the US.

3. China is the Most Stabile Superpower

(Countering America’s madness with China’s stability #以中国稳应对美国疯#)

A third stance that has been dominant in Chinese official online discourse is that China’s development does not rely on anyone’s favors (#中国发展从不靠谁的恩赐#, derived from a quote by Xi Jinping), and that despite the US’s measures, China’s rise on the world stage cannot be stopped. In fact, the narrative suggests that these actions by the US are only accelerating China’s ascent.

A commentary piece published by state broadcaster CCTV (@央视新闻) on April 11 quoted Professor Li Haidong (李海东) of China Foreign Affairs University, who stated that the US’s increasingly aggressive behavior reinforces the notion that it is using tariffs as a tool of extreme pressure; as a weapon to serve its own interests. According to Li, this reflects America’s hegemonic mindset, aiming to assert superiority by intentionally creating crises.

But rather than strengthening the US, the commentary argues, these recent measures are backfiring and are damaging the US’s domestic economy and undermining its global credibility.

In contrast to the US’s presumed recklessness and “hysterical approach,” China is depicted as a “responsible world leader,” bringing certainty to an uncertain world by “responding with its own stability” and proving to be, supposedly, a more reliable engine of global growth. The commentary states:

🇨🇳📢 “As the tariff storm strikes, China is using its own ‘stability’ to resist the trials and tribulations, by upholding rules, defending justice, and steering the big ship of globalization through treacherous countercurrents, toward the right path of openness and cooperation.”

To promote the piece on social media, CCTV used the hashtag “Responding to America’s madness with China’s stability” (#以中国稳应对美国疯#).

This sentiment was echoed by nationalist bloggers, such as Tangzhe Tongxue (@唐哲同学), who posted on April 13:

💬 “In this world, besides China, the rest are all just a poorly equipped small-town theater troupe (草台班子).”

The phrase “草台班子” (cǎotái bānzi) literally refers to a makeshift opera troupe performing on a shabby rural stage, and is used to describe an incompetent group of amateurs.

The blogger’s comment indirectly responds to comments made by US Vice President JD Vance, who defended Trump’s tariffs in a Fox News interview by saying: “To make it a little more crystal clear, we borrow money from Chinese peasants to buy the things those Chinese peasants manufacture.”

That remark sparked controversy online, with many netizens calling it ignorant. Some pointed out that Chinese people were already wearing fine silks when Westerners were still wrapped in animal skins fishing in the sea, and flipping the narrative to portray Americans as the real “country bumpkins.”

Meme shared online.

This sentiment was reinforced by another hashtag trending on Weibo on April 13: “You think we’re scared, but we actually don’t care” (#你以为我们scared其实我们不care#).

That line comes from a Channel 4 interview with Gao Zhikai (Victor Gao/高志凯), Vice President of the Center for China & Globalization (CCG), who stated:

🇨🇳📢 “China is fully prepared to fight to the very end. Because the world is big enough that the United States is not the totality of the market in the world. So if the United States wants to go in that direction of completely shutting itself out of the Chinese market, be my guest. [Interviewer: Yes and China will lose the US market..] We don’t care. We don’t care. China has been here for 5000 years, and for most of the time there was no United States and we survived. If the United States wants to bully China, we will deal with the situation without the United States. And we except to survive for another 5000 years.”

While this reflects the official position and is widely echoed across social media, others stress the importance of remembering history; particularly China’s “Century of Humiliation” (百年国耻), which was marked by war, aggression, and unequal treaties imposed by foreign powers. Just like other historical anniversaries, some bloggers argue that Trump’s tariff “D-Day,” April 9, should not be forgotten (“今天是每个中国人难以释怀的日子”) and that it marks another reason for China’s renewed rise.

In a video posted by CCTV’s short video platform Xiaoyang Shipin (小央视频) on April 13 (link), the narrator states:

🇨🇳📢 “The so-called global “beacon” now puts “America first.” It slaps allies in the face, treats the world with predatory practices, and makes other countries pay for MAGA, pushing the fragile word economy over the edge, and pitching itself against the whole world. With China here, the sky won’t fall. With around 5% economic growth, China adds the output of a mid-sized European economy every year. China has hundreds of millions of skilled workers. The Chinese people are well known for their strong work ethic. China’s development over the past seven decades is a result of self-reliance and hard work, not favors from others, (..) Global businesses believe the next China is still China and the best is yet to come (..) Markets need to restore faith. Between the pond of closed markets, and the ocean of economic interconnectivity, which one would you choose?”

Overall, packaged across different media — from hashtags to short videos, from press conferences to news reports, and from digital slogan posters to Ministry of Foreign Affairs tweets — China’s strategic political media messaging is clear and quite powerful, despite the fragile and censored environment it operates in: China is not afraid to strike back, China will lead with calm, and eventually, China will emerge as the winner. Whatever happens next remains to be seen, but when it comes to turning crisis into opportunity, China’s official media channels have already done just that.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: “THE US-CHINA TARIFF WAR ON CHINESE SOCIAL MEDIA“

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

Jiehun Huazhai (结婚化债): Getting Married to Pay Off Debts

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

Behind the Mysterious Death of Chinese Internet Celebrity Cat Wukong

Do You Know Who Li Gang Is? Anti-Corruption Official Arrested for Corruption

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Society10 months ago

China Society10 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoTeam China’s 10 Most Meme-Worthy Moments at the 2024 Paris Olympics

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoAbout Wang Chuqin’s Broken Paddle at Paris 2024

winona

May 13, 2018 at 8:15 pm

honestly, i like this. there’s so much pressure in chinese culture to exceed in studies (resulting in depression, anxiety and even suicide). academia isn’t for everyone. this is de-stigmatising average test scores and opens up the conversation for different careers. im very surprised and quite proud of china’s education department for promoting this campaign. i wish for china to keep moving towards progressive and open minded societal attitudes.