No Quiet Qingming

Published

10 months agoon

Dear Reader,

It’s been a tumultuous news week, with discussions and trending topics on Chinese social media going from international events like the Myanmar earthquake or the impeachment of South Korean (former) President Yoon Suk Yeol to major discussions on the safety and abuse of the autopilot feature on electric vehicles, the US trade war, and new military exercises around Taiwan.

🧹 With so much going on, this year’s Qingming Festival (清明节) felt especially welcome. Also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day, Qingming fell on April 4 this year. It is a special time to reflect, pause, and honor family ancestors by visiting graves, making offerings, and burning spirit money.

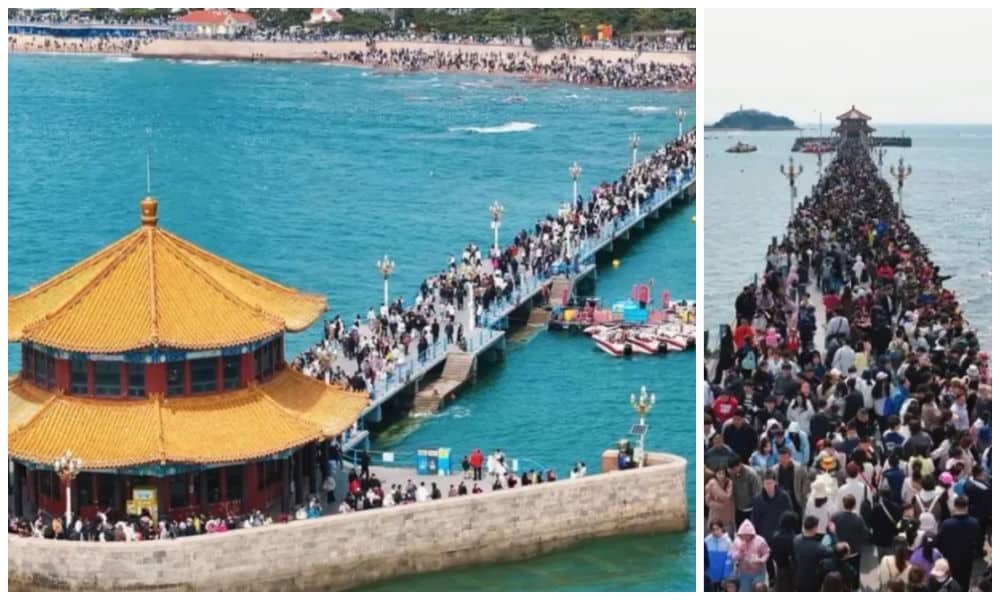

🧳 It’s also a public holiday and a popular time for travel. And so, instead of a quiet time, many popular tourist spots across China turned into a sea of people. One example is Qingdao, where the famous Zhanqiao Pier (栈桥) — the one featured on the Tsingtao Beer label — became more people than pier. That crowded hotspot scene sparked the trending hashtag “#人人人人栈桥人人人人#”: People-People-People-People-Zhanqiao-People-People-People-People.

More people than pier in Qingdao, images via Qingdao Daily 青岛日报

On Chinese social media, it has become somewhat of a tradition to post about just how busy it is at China’s various sightseeing spots. This is often done using the hashtags “人人人人[place]人人人人” or “人人人人[me]人人人人.” The character 人 (rén) means person or human; “人人” (rénrén) means “everyone,” and the more “人人人” (rén rén rén) are used, the more it playfully emphasizes the crowds of people.

Since it was also very crowded this weekend at Hangzhou West Lake, Mount Qingcheng, the Longmen Grottoes, the Hubei Provincial Museum (people lining up to see the Sword of Gouijan), and many other places, there were similar hashtags for various places going around Weibo.

📰 Qingming Festival is also a busy time for state media, as the holiday ties into broader narratives about the nation and remembering those who defended the homeland. State media-initiated hashtags like “Forever Remember [for] the Homeland, Salute to Our Heroes” (#家国永念致敬英雄#) are used in posts about key commemorations — such as the China Coast Guard observing a moment of silence facing the sea and scattering flowers in honor of China’s martyrs.

CCTV poster 家国永念, Always Remember the Homeland.

One especially notable grave visit covered by the media this weekend was that of Mao Xinyu (毛新宇), the only surviving grandson of Mao Zedong. He returned to Mao’s birthplace, Shaoshan, with his family to pay tribute to his grandfather. At the statue of Mao, great-granddaughter Mao Tianyi (毛甜懿) also spoke a few words, wishing her great-grandfather peace and expressing hope that she could live up to his expectations (see video).

💸 For China’s paper offering businesses, the period around Qingming Festival is anything but quiet. Over the past years—and especially in the age of booming e-commerce—the ancient ritual of paper offerings has undergone major transformations and become increasingly extravagant. By burning ritual paper gifts, it’s believed that these offerings are sent to the afterlife.

To please the ancestors—and perhaps sometimes to impress the neighbors, too—people now burn all kinds of things, from paper liquor to cardboard Rolex watches.

Some take it a step further, creating entire paper replicas of two-story villas or palaces to honor their ancestors. Chinese media reported that one vendor in Jiangsu’s Nantong was selling a 200 m² paper villa, complete with rooms, for 15,000 yuan ($2,060)—it even had a car in the driveway (video)! Another video showed neighbors gathering to watch such a paper mansion go up in flames.

This year, one item that particularly caught attention on WeChat and Xiaohongshu was a paper version of the Xiaomi SU7 EV. A video showing these offerings strapped to the back of a delivery scooter went viral—apparently, Xiaomi is more popular than BMW this year (read last year’s article about Burning BMWs here).

🪦 At least for the people visiting their family’s graves and bringing offerings, Qingming should be a relaxing time, right? Not exactly — or at least, not for everyone. This year, the Qingming Festival ancestral worship activities of the “South China F3” (华南F3, referring to Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan) have sparked widespread discussion for just how dramatic and hardcore they can get.

Many people in these southern provinces, especially in rural and mountainous areas, have become known for going all out when it comes to ancestral worship during Qingming. Climbing mountains, entering caves, wading through rivers — some ancestral graves are so hidden that tomb-sweeping day feels more like a wilderness survival challenge for the families trying to reach them.

On Friday, Toutiao News reported that new technologies are now helping people pay respects when graves are located in remote, hard-to-access areas. Since 2021, one entrepreneur from Guangxi has been using drones to deliver offerings into the mountains. GPS apps help track routes to ancestral tombs, and robotic dogs are even being used to carry food and offerings up steep paths.

So while technology is making ancestral rites more efficient, it’s also adding new layers of intensity to rituals that perhaps were never meant to be fast-paced in the first place.

📱🐼 IShowSpeed and the Seven China Streams

Robots, drones, flying cars — they are not just becoming part of China’s old traditions, they’re also a major part of China’s new narratives, and this was particularly clear this week in the many hours of livestreaming by the famous American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Jason Watkins Jr.).

After Shanghai, Beijing, and the Shaolin Temple in Henan, IShowSpeed continued to livestream from Chengdu, Chongqing, Hong Kong, and Shenzhen. His seven China streams together make up over 43 hours of footage, and I’ll admit that I’ve seen the great majority of it.

Last week, I already did a deep dive into the significance of IShowSpeed’s China tour, and how his streams have been used by Chinese official channels and state media as part of the strategy to tell China’s story well, and also to spread China’s message effectively — preferably through genuine and engaging stories. (In case you missed it, read the analysis here).

This week’s streams showed that both IShowSpeed’s team and the Chinese coordinators behind the scenes were even better prepared for the livestreamed visits and the enormous spectacle it brings to the places he goes. Some Chinese state media even started livestreaming his streams as well.

In just ten days, Watkins has become a mega-celebrity in China, where he wasn’t that famous before — and he’s been trending on social media practically every day since March 24. Outside of China, his influence is also growing. During his Hong Kong stream, he reached a personal record of 38 million YouTube subscribers.

IShowSpeed is no longer just an American personality — he’s a marketing platform. Chinese authorities, state media, companies, brands, e-commerce channels, and influencers are all jumping in on the hype to benefit from his popularity.

From the top-down narrative perspective, his China tour has been a huge success. Kung fu performances, traditional opera, pandas, Chinese dance and music, local cuisine highlights, the Great Wall, traditional medicine and yin-yang, futuristic cities alongside ancient culture, high-speed rail, noodles, dancing aunties, and Shaolin monks — his streams became an ultimate representation of the Chinese cultural promotion playbook, and were reported on as such. China’s national broadcaster CCTV aired an entire 8-minute segment on his China tour, covering his adventures.

When Watkins’ livestreams started to include aerial drone footage with spectacular views — and especially when dancing with robots was added to the list of activities — I couldn’t help but see a resemblance between his 5+ hour stream and the famous Spring Festival Gala: a tightly programmed spectacle featuring Chinese opera, kung fu, and traditional cultural highlights mixed with cutting-edge technology.

Watkins’ latest visit to Shenzhen especially became a celebration of Chinese tech. Not only did he do the robot dance and purchase three Huawei Mate X3 tri-fold phones (he also got futuristic BYD Yangwang U9 in Chongqing), the city had also organized a spectacular dragon drone show.

Watkins also took a ride in a “flying car” — the EH216-S by tech company EHang (亿航). Just last week, EHang received official approval to operate the aircraft in China. While these flying vehicles will mainly be used for tourism and sightseeing at first, they’re expected to be part of low-altitude urban commuting in the future. Starting later this year, you’ll be able to try it out yourself in Hefei, where public tourism flights will begin.

No wonder the EHang team was thrilled with the exposure. Besides a cultural ambassador to China, IShowSpeed’s been the best brand ambassador they could’ve hoped for.

At the same time, Watkins is anything but quiet, and his chaotic streams haven’t exactly brought moments of reflection during this year’s Qingming Festival. Today is a free day for him, offering some peace and quiet — for him, his team, and the entire circus surrounding the tour.

Wishing you a calm Sunday! Check out the rest of the newsletter below. Special thanks to Miranda Barnes for contributing to this week’s issue. As always, thank you for your support — and don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions or suggestions📨.

Best,

Manya (@manyapan)

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactios to Trump’s Tariffs

Featured

“China’s countermeasures are here” (#中方反制措施来了#). This hashtag, launched by Party newspaper People’s Daily, went top trending on Chinese social media on Friday, April 4, after President Trump announced steep new tariffs on Wednesday, including a universal 10 percent “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods and especially targeting China with an additional 34% reciprocal tariff as part of so-called “liberation day.”

Trump’s tariffs, and Chinese countermeasures, have sparked all kinds of reactions on Chinese social media. Much of the popular online conversation has focused on concrete examples of what kinds of things might get more expensive for Chinese consumers in their everyday lives, and how the people should change crisis into opportunity by “smart buying” Chinese brands and products: “This moment is the time to reflect on our unity. If we can choose domestic alternatives, we should.”

What Else Has Been Trending?

Roundup of curated top trends and noteworthy discussions

💄Nanjing Mall Fake Gucci Lipstick Controversy

It’s just a small product, but it sparked a big controversy this week: a fake Gucci lipstick went viral after a female netizen named Miao (苗) shared with her followers how a Gucci sales associate sold her a counterfeit item. Her post quickly drew hundreds of reactions, and she was then targeted with a wave of nasty comments, seemingly from Gucci staff using burner accounts. Not getting the help she expected, Miao initiated a quality control check of the lipstick herself, which confirmed the Gucci lipstick was indeed not authentic.

So why did this incident blow up? The lipstick was sold by an official Gucci beauty counter at Nanjing’s Deji Plaza (德基广场), which is one of the city’s largest and most high-end shopping malls, featuring luxury brands like Louis Vuitton, Cartier, Dior, and Hermes. It wasn’t just the fake product that sparked outrage, but also Gucci and Deji Plaza’s poor PR response. At the heart of the backlash is a deeper concern: if consumers can’t even trust the products sold at Gucci’s own counter in a place like Deji Plaza, how can they have any confidence in the authenticity of luxury goods at all?

This story is definitely getting a follow-up.

💥 Fatal Xiaomi SU7 Crash

The Xiaomi SU7 has been trending in China all week following a tragic accident in Anhui that killed three people. The incident occurred on March 29 on the Zongyang Expressway, where the electric vehicle reportedly hit the guardrails and caught fire. According to Xiaomi’s own records, the vehicle had been in smart driving mode for about fifteen minutes before the crash. At 22:44:24, the system alerted the driver to an obstacle ahead. The driver then took over, but the collision occurred just two to four seconds later (report in Chinese).

Beyond the smart driving function, scrutiny has also turned to the car’s battery system and the automatic emergency braking (AEB) feature. Xiaomi has stated it is cooperating with the official investigation.

Adding further fuel to public debate over the safety of semi-autonomous EVs is a separate incident that went viral this week in Zhejiang. A video (see here) shows a Xiaomi car owner fast asleep at the wheel, with both hands off the steering wheel. While Xiaomi trended – a related hashtag received over 150 million views on Weibo (#网友曝小米汽车车主驾驶中睡着#) – some popular commenters argued that the real issue wasn’t the car, but a reckless driver whose license should be revoked.

Seeing all of these discussions on Chinese social media about the dangers of relying on autopilot features in EVs, it’s no wonder that another recent viral video showing a parent asleep behind the wheel of a moving car, with a child sleeping in the backseat, is sparking angry reactions—like: ‘Not only should their license be revoked, they should also temporarily lose custody and be required to take a parenting exam’ (see video here)

🏛️ Yoon Suk Yeol Removed as South Korea’s President

On April 4, the name Yoon Suk Yeol (尹锡悦) began trending on Chinese social media. That Friday morning, South Korea’s Constitutional Court unanimously voted to uphold the impeachment of the (former) president for violating the constitution and abusing presidential powers when he declared martial law in December. With Yoon’s removal from office, a new presidential election must be held within 60 days.

On Weibo, some of the most popular comments described his impeachment as “to the satisfaction of everyone” (dà kuài rén xīn 大快人心) and “as expected” (yì liào zhī zhōng 意料之中). Others focused on the historical significance of Yoon’s impeachment: following Park Geun-hye in 2017, Yoon is now the second South Korean president to be removed from office. Ironically, it was Yoon himself—then a lead prosecutor—who played a key role in the investigation that sent Park Geun-hye to jail. Yoon also becomes the shortest-serving president in South Korea’s democratic history.

What’s Noteworthy

Small News with Big Impact

After visiting Shanghai, Beijing, and the Shaolin Temple in Henan, popular American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins) livestreamed from Chengdu on March 31.

During his stream, he visited a Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioner, tried acupuncture, had some extremely spicy hotpot, and continued doing the kinds of activities that have defined his China tour so far – from kung fu to the Forbidden City.

But not everything has gone smoothly. In Chengdu, with as many as 4 million viewers watching the livestream on Douyin, one moment in particular sparked controversy online. Just before Watkins entered a car, a girl in cosplay attire approached him and said something truly bizarre. Read more below.

This is the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here.

You are receiving this email because you opted in via our website. Don’t want to receive these emails? Unsubscribe .

Copyright (C) 2025 What’s on Weibo. All rights reserved.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Society

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

From 5,000 people crashing a rural pig feast in Chongqing to the collective effort to save Yanran Angel hospital.

Published

6 days agoon

January 22, 2026

🔥 China Trend Watch (1.22.26)

Part of Eye on Digital China by Manya Koetse, China Trend Watch is an overview of what’s trending and being discussed on Chinese social media. The previous newsletter was a deep dive into the Dead Yet? app phenomenon. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Not a day goes by these days when Trump isn’t trending. Whether it’s about Venezuela and Greenland, ICE, or his recent speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, his name keeps popping up in the hot lists.

However, there are dozens of other topics being discussed on Chinese social media that actually aren’t about the US or the shifting geopolitical landscape. From football to pig-slaughter feasts, from a Henan grandpa in Paris to the latest birth rates, there is an entire world of topics out there that’s blissfully unconnected to anything happening in Washington or Davos — with many of these discussions signaling bigger social stories unfolding in China today. Let’s dive in.

Quick Scroll

- 🐶 “Eat more dog meat,” a local Community Health Service Center in Ya’an advised in a seasonal health text, suggesting it would help people stay healthy & warm during cold weather. The message sparked controversy among dog lovers online. The center later apologized and issued a corrected version, replacing dog meat with lamb, beef, and chestnuts.

- ⚽ Chinese goalkeeper Li Hao (李昊) is the man of the moment after China’s under-23 national football team beat Vietnam (0-3) and advanced to the final of the AFC U23 Asian Cup. It marks the first time since 2004 that any Chinese men’s national team (at any level) has reached the final of a continental tournament. In the final, China will face Japan.

- 👶 China’s latest birth data for 2025 are in, showing yet another record low. The birth rate fell to 5.63 per 1,000 people, with 7.92 million babies born last year — a 17% year-on-year decline.

- 💸 An “underground” private tutoring operation in Beijing has been hit with a staggering fine of more than 67 million yuan (US$9.6 million) for offering after-school classes without official approval. It’s the highest fine so far under China’s “Double Reduction” policy, introduced in 2021 to curb private tutoring and ease academic pressure on students.

- 🕯️ He Jiaolong (贺娇龙), a Xinjiang local official who was at the forefront of Chinese officials livestreaming & promoting their regions in creative online ways, died this week after a fatal fall from a horse during work-related filming. She was 47 years old.

- 🎭 Another death that trended this week was that of renowned Chinese comedian Yang Zhenhua (杨振华, b. 1936), a crosstalk (相声) artist remembered for his classic performances and widely regarded as a cultural icon.

- 🏛️ A child abuse case that has haunted Chinese netizens for the past two years has come to a close. Xu Jinhua (许金花), the stepmother who tortured and starved her 12-year-old stepdaughter, known as “Qiqi,” to death, was executed on January 20. Xu was sentenced to death in April 2025, and her appeal was rejected last November.

What Really Stood Out This Week

1. Mass Shutdowns of Local Chinese Pig-Slaughter Feasts

Annual pig feasts are traditionally meant to be a source of community bonding and ritual exchange. But for many towns and districts, páozhūyàn (刨猪宴), traditional pig-slaughter feasts, have now become a source of concern, leading to shutdowns of local events across multiple provinces.

The story begins on January 9, when a farmer’s daughter nicknamed Daidai (呆呆) from Hezhou in Chongqing posted a lighthearted message on Douyin asking whether people could help with her family’s pig slaughter, saying her old dad would not be able to hold down the two pigs. In return, she promised to treat helpers to “pork soup and rice,” adding: “To be honest, I just want the road in front of my house to be packed with cars, even more than at a wedding. I want to finally prove myself in the village!”

Two days later, on January 11, when the pig feast took place, Daidai got more than she had asked for. Not only was the road in front of her home packed with cars — the entire village was completely blocked as over 1,000 cars and some 5,000 visitors arrived. With two pigs nowhere near enough, five pigs ended up being slaughtered. Livestreamers flooded the scene, Daidai’s name was quickly trademarked, and before she knew it, she had entered internet history — including her own Baidu page — as the girl who turned a local gathering into a national feast.

Daidai (middle) hadn’t expected her call for help with slaughtering two pigs would end up in 5000 people coming to her town.

By now, the incident has spiraled into a much bigger issue, as others in the Sichuan–Chongqing region want to replicate the viral success of Hechuan, creating chaos and sometimes unsafe situations by turning neighborhood moments into tourist activities. This has led to a series of events being canceled or shut down.

On January 14, a planned páozhūyàn, initiated by local influencer Jia Laolian (假老练) in Longquanyi District in Chengdu, had to be canceled at the last minute after thousands of people registered to attend. On January 17, an online influencer in Caijiagang Subdistrict, Chongqing, also held a free pig-slaughter feast that quickly led to potentially dangerous overcrowding. Police shut it down. Another event took place in Ziyang, where 8,000 people had registered to attend while there were only 200 parking spaces available. There were more.

The current hype surrounding these pig-slaughter events reflects a sense of urban–rural nostalgia for local traditions and human connections, but probably says more about how viral tourism in China has worked since the frenzy surrounding Zibo: at lightning speed, influencers and local tourism bureaus jump onto fast-moving trends, hoping to get their own viral moment and, quite literally, piggyback on it.

While these moments can create a moment of hype, the downsides are clear: a lack of oversight, weak crowd management, intrusion to local communities, and lives being suddenly disrupted. For now, ‘Daidai’ has gained about two million users on her social media account. She says she hopes to do “something meaningful” with her online influence and has become an organic ambassador for Hechuan. At the same time, she also wants some calm after the storm, saying:“The Zhaozhu Yan in Heichuan has concluded successfully. I hope everyone can return to their normal lives. I also hope my parents can go back to their previous life—I don’t want them dragged into the internet world.”

2. How a Hospital Crisis Won China’s Trust

Usually, when news emerges about Chinese celebrities facing debts or court papers, it signals a serious blow to their reputation. But in a case that trended over the past week involving Chinese actor/businessman Li Yapeng (李亚鹏) and singer/pop icon Faye Wong (Wang Fei 王菲), the opposite is true.

Li and Wong were previously married and are parents to a daughter born with a cleft lip and palate. Their experiences in getting treatment and surgery for their daughter led them to become deeply involved with the efforts to help other children. In 2006, they founded the Yanran Angel Foundation (嫣然天使基金). A few years later, they established the Yanran Angel Children’s Hospital (嫣然天使儿童医院), China’s first privately-operated non-profit children’s hospital, providing surgeries, orthodontics, speech therapy, and other support to thousands of children—many of them at no cost for underprivileged families.

For the first ten years that Li and his team leased the hospital location, the landlord provided them with heavily discounted rent as a sign of his goodwill. In 2019, that agreement ended, and the rent doubled to market value at 11 million yuan per year (over US$1.5 million). But then Covid hit, and while the hospital still had all of its staffing and lease costs, surgeries were postponed.

On January 14 this year, Li Yapeng posted a lengthy video on his Douyin account titled “The Final Confrontation” (最后的面对), in which he explains how they fell behind on their rent since 2022, now finding themselves in a debt of 26 million yuan (over US$1.5 million) and facing a court judgement that leaves them with little choice but to vacate the premises and shut the hospital down.

Something that struck a chord with netizens is how Li, who bears joint liability for the unpaid rent, made no excuses and openly acknowledged his legal obligations, while at the same time emphasizing his personal sense of responsibility to ensure that children waiting for surgery would still receive the help that had been promised to them.

Public perception of Li Yapeng, who was previously seen as a failed businessman, transformed overnight. He was suddenly hailed as a hero who had quietly devoted himself to charity all this time, while accumulating personal debts.

Donations started flooding in. Within two days, over 180,000 people had donated a total of 9 million yuan (US$1.3 million), and by January 19 this had grown to more than 310,000 people supporting the hospital with nearly 20 million yuan (US$2.8 million). Beyond direct donations, netizens also supported Li Yapeng by tuning into his e-commerce livestreams. One businessman from Jiangsu even offered 30,000 square meters of free space for the hospital to relocate.

Meanwhile, netizens began wondering why Faye Wong, Li’s ex-wife with whom he had founded the foundation and hospital, was staying quiet. Just as some started to label her a diva who no longer cared about the cause, a 2023 audit report revealed that since divorcing Li Yapeng in 2013, she had been anonymously donating to the fund every year for a decade, totaling more than 32.6 million yuan (US$4.6 million) to cover rent and staff salaries.

There are many aspects to this story that have caused it to go viral, and that make it particularly noteworthy. It is not just the turnaround in public sentiment regarding Li and Faye Wong, but also the fact that people are more willing to donate to a cause they genuinely believe in. Although Li and Wong’s foundation technically falls under the Red Cross system, that organization has faced significant criticism and public distrust in China over the years.

What also helps are the personal stories shared on social media by those who have had direct experience with the hospital, or who know people working there. These include deeply moving accounts from families who saw all their savings depleted while trying to get proper care for their three-year-old child born with a cleft lip, then traveling for days from Gansu to Beijing with little more than a sliver of hope—only to learn that their child would not only receive surgery for free, but that the hospital would also help cover temporary lodging and travel costs. Many feel that causes like this are rare, and deserve to continue.

After years of stories about celebrities evading taxes, good causes misspending money, and corruption getting mixed up with charity, this is a story that restores trust — showing that some celebrities truly care, that some charities do turn every penny into help for those in need, and that netizens can genuinely make a difference. “This is the most heartwarming news at the start of the year,” one Weibo commenter wrote.

For now, it remains unclear whether the hospital can remain at its current location, but operations continue, and negotiations are ongoing. Fundraising has been paused for the time being, as annual donation targets have already been exceeded.

3. The Sudden Death of a 32-Year-Old Programmer and the Renewed Debate Over China’s Tech Overtime Culture

The sudden death of a 32-year-old programmer who worked at a tech company in Guangzhou is sparking discussion these days, as his death is being linked to the extreme overtime work culture in China’s tech sector.

The story is attracting online attention mainly because his wife, using the nickname “Widow” (遗孀), has been documenting her grieving journey on social media, sharing stories about how she misses her late husband and the things she wishes had gone differently. He was always working late, and she often asked him to come home when he still hadn’t returned by 10:00, 11:00 p.m., or even midnight.

Gao Guanghui (高广辉) worked as a software engineer and department manager. Despite his “seriously overloaded” working schedule, his now-widowed wife describes their life together as “very happy.”

On Saturday, November 29, 2025, the day of his passing, Gao mentioned that although he was feeling unwell, he still had work matters with approaching deadlines to handle. Browser records show that he accessed the company’s internal system at least five times that morning before fainting and experiencing sudden urinary incontinence.

While preparing to go to the hospital, Gao reportedly urged his wife to bring his laptop with them so that he could finish his tasks. However, he collapsed before the two had even gotten into the car. Despite an ambulance arriving at 9:14 a.m. and efforts to save him, he passed away two hours later. He died of cardiac arrest, and hospital records note his high-pressure, long-hour work schedule.

Even in the final moments of his life, work continued to intrude. Gao was added to a work WeChat group at 10:48 a.m., while hospital staff were still attempting to resuscitate him. Hours after his death was declared, colleagues continued to send him work messages, including one at 9:09 p.m. asking him to urgently fix an issue.

Making matters worse, Gao’s widow says that in the second week after his death, his company had already processed his resignation and disposed of his belongings. The items that were sent to her were crushed and poorly packed. To this day, she says she has received no apology, no compensation, no replacement items, and none of her husband’s missing belongings.

Visuals dedicated to Gao, shared on Xiaohongshu.

On social media, people are angry. Reading about Gao’s life story — and how he was always a hard worker, sometimes working two jobs at a time — many comments indicate that it is often the most dedicated ones who get pressured the most. They see him as a victim of tech companies like CVTE that go against official guidelines and perpetuate a work culture where working overtime becomes the norm, only leading to more workload.

This is not the first time such a story has gone viral. In 2021, the death of an employee who worked at Pinduoduo triggered similar discussions about strenuous “996” schedules (working 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days per week).

Similar deaths include the 2011 case of 25-year-old PwC auditor Pan Jie, whose story went viral on Sina Weibo after doctors concluded that overwork may have played a crucial role in her death. Likewise, the at-desk death of a 24-year-old Ogilvy employee in Beijing and the 2016 death of Jin Bo, deputy editor-in-chief of one of China’s leading online forums, also prompted calls for greater public awareness of the risks of overwork — especially among young professionals.

On the Feed

“Paris Without the Filter”

“Filter-Free Paris,” or “Paris without a filter” (素颜巴黎), unexpectedly went viral after a grandpa from China’s Henan province, traveling with a senior tour group, shared his unfiltered and casual photos of rainy Paris. In an age when European travel photos are often heavily filtered and glamorized on Chinese social media, many found the grandpa’s grey, plain images of the “City of Romance” not only amusing but also refreshingly honest.

Seen Elsewhere

• A Chinese state media editorial framed the Greenland dispute as a “wake-up call” for Europe to reduce its reliance on the US. (CHINA DAILY)

• Why Western “Chinamaxxing” and “very Chinese time” memes say more about a “decay of the American dream” than about China itself. (WIRED)

• WIRED seems to be at a “very Chinese time” itself, and also launched its China issue, introducing 23 ways you’re already living in the ‘Chinese Century.’ (WIRED)

Title/Image via Wired, Andria Lo

• As Trump sows division, China says it’s the calm, dependable leader the world needs. (CNN)

• Nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution has become one of the few legally viable means of resistance, according to Shijie Wang. (CHINATALK)

That’s a wrap! Thanks for reading.

If you happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

See you next edition!

— Manya

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo. Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. If you no longer wish to receive these newsletters, or are receiving duplicate editions, you can unsubscribe at any time.

China Digital

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

A virtual Viagra for a pressured generation? The real story behind China’s latest viral app.

Published

2 weeks agoon

January 14, 2026

From censored joke to state-friendly app, ‘Are You Dead Yet?’ has traveled a long road before reaching the top of China’s paid app charts this week. While marketed as a tool for those living alone to check in with emergency contacts, the app’s viral success actually isn’t all about its features.

It is undoubtedly the most unexpected app to go viral in 2026, and the year has only just started. “Are You Dead?” or “Dead Yet?” (死了么, Sǐleme) is the name of the daily check-in app that surged to the No. 1 spot on Apple’s paid app chart in China on January 10–11, quickly becoming a widely discussed topic on Chinese social media. It has since become a top-searched topic on the Q&A platform Zhihu and beyond, and by now, you may even have noticed it appearing on your local news website.

For many Chinese who first encountered the app, its name caused unease. In China, casually invoking words associated with death is generally considered taboo, seen as causing bad luck. It was therefore especially noteworthy to see state media outlets covering the trend. The fact that the name plays on China’s popular food delivery platform Ele.me (饿了么, “Hungry Yet?”), a household name, may also have softened the linguistic sensitivity.

Beyond the name, attention soon shifted to the broader social undercurrents and collective anxieties reflected in the app’s sudden popularity.

🔹 “A More Reassuring Solo Living Experience”

Are You Dead Yet? is a basic app designed as a safety tool for people living alone, allowing them to “check in” with loved ones. The Chinese app has been available on Apple’s App Store since 2025 and currently costs 8 yuan (US$1.15) to download.

The app is very straightforward and does not require registration or login. Users simply enter their name and an emergency contact’s email address. Each day, they tap a button to virtually “check in.”

If a user fails to check in for two consecutive days, the system automatically sends an email notification to the designated emergency contact the following day, prompting them to check on the user’s safety.

The app was created by Guo Mengchu (郭孟初) and two of his Gen Z friends from Zhengzhou, all born after 1995. Together, they founded the company Moonlight Technology (月境技术服务有限公司) in March 2025, with a registered capital of 100,000 yuan (US$14,300). The app was reportedly developed in just a few weeks at a cost of approximately 1,000 yuan (around US$143).

In the text introducing the Dead Yet? app, the makers write that the app is specifically intended to “build seamless security protection for a more reassuring solo living experience” (“构建无感化安全防护,让独处生活更安心”).

🔹 The Rise of China’s Solo-Living Households

The number of solo households in China has skyrocketed over the past three decades. In the mid-1990s, only 5.9% of households in China were one-person households. By 2011, that number had nearly tripled from 19 million to 59 million, accounting for nearly 15% of China’s households.1,2 By now, the number is bigger than ever: single-person households account for over 25% of all family households.3

These roughly 125 million single-person households are partly the result of China’s rapidly aging society, along with its one-child policy. With longer life expectancies and record-low birth rates, more elderly people, especially widowed women, are living alone without their (grand)children.

China’s massive urban-rural migration, along with housing reforms that have adapted to solo-living preferences, has also contributed to the fact that China is now seeing more one-person households than ever before. By 2030, the number may exceed 150 million.

But other demographic shifts play an increasingly important role: Chinese adults are postponing marriage or not getting married at all, while divorce rates are rising. Over the past few years, Chinese authorities have introduced various measures to encourage marriage and childbirth, from relaxed registration rules to offering benefits, yet a definitive solution to combat China’s declining birth rates remains elusive.

🔹 A “Lonely Death”: Kodokushi in China

Especially for China’s post-90s generation, remaining unmarried and childless is often a personal choice. On apps like Xiaohongshu, you’ll find hundreds of posts about single lifestyles, embracing solitude (享受孤独感), and “anti-marriage ideology” (不婚主义). (A few years back, feminist online movements promoting such lifestyles actually saw a major crackdown.)

Although there are clear advantages to solo living—for both younger people and the elderly—there are also definite downsides. Chinese adults who live alone are more likely to feel lonely and less satisfied with their lives 4, especially in a social context that strongly prioritizes family.

Closely tied to this loneliness are concerns about dying alone.

In Japan, where this issue has drawn attention since the 1990s, there is a term for it: kodokushi (孤独死), pronounced in Chinese as gūdúsǐ. Over the years, several cases of people dying alone in their apartments have triggered broader social anxiety around this idea of a “lonely death.”

One case that received major attention in 2024 involved a 33-year-old woman from a small village in Ningxia who died alone in her studio apartment in Xianyang. She had been studying for civil service exams and relied on family support for rent and food. Her body was not discovered for a long time, and by the time it was found, it had decomposed to the point of being unrecognizable.

Another case occurred in Shanghai in 2025. When a 46-year-old woman who lived alone passed away, the neighborhood committee was unable to locate any heirs or anyone to handle her posthumous affairs. The story prompted media coverage on how such situations are dealt with, but it drew particular attention because cases like this had previously been rare, stirring a sense of broader social unease.

🔹 The Sensitive Origins of “Dead Yet?”

Knowing all this, is there actually a practical need for an app like Dead Yet? in China? Not really.

China has a thriving online environment, and its most popular social media apps are used daily by people of all ages and backgrounds, across urban and rural areas alike. There are already countless ways to stay in touch. WeChat alone has 1.37 billion monthly active users. In theory (even for seniors) sending a simple thumbs-up emoji to an emergency contact would be just as easy as clocking in to the Dead Yet? app.

The app’s viral success, then, is not really about its functionality. Nor is it primarily about elderly people fearing a lonesome death. Instead, it speaks to the dark humor of younger adults who feel overwhelmed by pressure, social anxiety, and a pervasive sense of being unseen—so much so that they half-jokingly wonder whether anyone would even notice if they collapsed amid demanding work cultures and family expectations.

And this idea is not new.

After some online digging, I found that the app’s name had already gone viral more than two years earlier.

That earlier viral moment began with a Zhihu post titled “If you don’t get married and don’t have children, what happens if you die at home in old age?” (“不结婚不生孩子,老后死在家中怎么办”). Among the 1,595 replies, the top commenter, Xue Wen Feng Luo (雪吻枫落), whose response received 8,007 likes, wrote:

💬 “You could develop an app called “Dead Yet?” (死了么). One click to have someone come collect the body and handle the funeral arrangements.”

The original post that started it all. That humorous comment was the initial play on words linked to food delivery app Eleme (饿了么).

Two days later, on October 8, 2023, comedy creator Li Songyu (李松宇, @摆货小天才), also part of the post-90s generation, released a video responding to the comment.

In it, he presented a mock version of the app on his phone: its logo a small ghost vaguely resembling the Ele.me icon, and its interface showing some similarities to ride-hailing apps like Uber or Didi.

In the video, Li says:

🗯️ “Are You Dead Yet?’ I’ve already designed the app for you. (…) The app is linked to your smart bracelet. Once it fails to detect the user’s pulse, someone will immediately come to collect the body. Humanized service. You can choose your preferred helper for your final crossing, personalize the background music for cremation and burial, and even set the furnace temperature so you can enter the oven with peace of mind. Big-data matching is used to connect people who might have known each other in life, followed by AI-assisted cemetery matching for the afterlife traffic ecosystem—you’ll never feel alone again. After burial, all content on your phone is automatically formatted to protect user privacy and eliminate worries about what comes after. There’s a seven-day no-reason refund, almost zero negative reviews, and even an ‘Afterlife Package’ with installment payments. Invite friends to visit the grave and have them help repay the debt. And if not everything turns to ashes properly, or if you’re dissatisfied with the shape of the remains, you can invite friends to burn them again and get the second headstone at half price! How about that? Tempted?”

The original “Sileme” or “Dead Yet” app idea, October 2023.

The video went viral, drew media coverage (one report called the concept and design of the “Are You Dead?” app “unprecedented”), and sparked widespread discussion. Although viewers clearly understood that the idea—one click and someone arrives to collect the body and arrange the funeral—was a joke, it nevertheless struck a chord.

Many saw the video as a glimpse into China’s future, arguing that with extremely low birth rates and a rapidly aging society, such business ideas might one day become feasible. Some people pointed to Japan’s growing problem of elderly people dying alone, suggesting that China may come to face similar challenges. At the same time, it also sparked concerns about increasing social isolation.

Despite its popularity, both the video and the trending hashtag “Dead Yet App” (#死了么APP#) were taken offline. A comedy podcast episode discussing the concept—“Did Someone Really Create the ‘Dead Yet’ App?” (真的有人做出了“死了么”APP?), released on October 10, 2023 by host Liuliu (主播六六)—was also removed.

According to Li Songyu himself, the video went offline within 48 hours “for reasons beyond one’s control” (“出于不可抗因素”), a phrase often used to avoid explicitly referring to top-down decisions or censorship.

It is not hard to guess why the darkly humorous Dead Yet? concept disappeared. And it wasn’t only because of crude jokes or the sensitivities surrounding death.

The video appeared less than a year after the end of China’s stringent zero-Covid policies, which had been preceded by protests. In both early and late 2023, Covid infections were widespread and hospitals were overcrowded. It was therefore a particularly sensitive moment to joke about bodies, afterlife logistics, and people being “taken away.”

Moreover, 2023 was a year in which state media strongly emphasized “positive energy,” promoting stories of heroism, self-sacrifice, and resilience in the face of hardship. It was not a time to dwell on death, and certainly not through humor.

🔹 Why a Censored Idea Became a ‘State-Friendly’ App

In 2025, things looked very different. Just weeks after the current Dead Yet? app was developed, it was released on the App Store on June 10, 2025. Not only was its name identical to the app “introduced” by Li in 2023, but its logo was also a clear lookalike.

The 2023 logo and 2025 “Dead Yet?” logo’s.

Although Li Songyu published a video this week explaining that he and his team were the original creators of the Dead Yet? concept and that they had planned to develop a real app before the idea was censored (without ever registering the trademark), app creator Guo Mengchu has simply stated that the inspiration for their app came “from the internet.”

In the same interview, Guo also emphasized that the app’s sudden rise was entirely organic, with the whole process of “going viral,” from ordinary users to content creators to mainstream media, taking about a day and a half.5

However, the app’s actual track record suggests a much bumpier journey.6 Since its launch, it has been taken down once and was reportedly removed from the App Store rankings three times. Such removals commonly occur due to suspected artificial download inflation, ranking manipulation, or other compliance-related issues.

After the most recent delisting on December 15, 2025, the app returned to the App Store on December 25—and only then did it finally have its breakthrough moment.

📌 Looking at how online discussions unfolded around the app, it becomes clear that, just as in 2023, the idea of relying on technology to ensure someone will notice if you die strongly resonates with people. Many users also seem to have downloaded it simply as a quirky app to try out. Once curiosity set in, the snowball quickly started rolling.

📌 But Chinese state media have also played a significant role in amplifying the story. Outlets ranging from Xinhua (新华) and China Daily (中国日报) to Global Times (环球时报) have all reported on the app’s rise and subsequent developments.

🔎 Why was Li Songyu’s Dead Yet? app idea not allowed to remain online, while Guo’s version has been able to thrive? The difference lies not only in timing, but also in tone. Li’s original concept leaned more clearly toward implicit social critique & satire. Guo’s app, by contrast, has been framed — and received — with far less overt sarcasm. While many netizens may still interpret it as dark humor, within official narratives it aligns more neatly with the family-focused social discourse, and perhaps even functions as an implicit warning: if you end up alone, you may literally need an app to ensure you do not die unnoticed.

In this way, the young creators of the new app are, perhaps inadvertently, contributing to an ongoing official effort in media discourse and local initiatives to encourage Chinese single adults to settle down and start a family. For them, however, it is a business opportunity: more than sixty investors have already expressed interest in the app.

Funnily enough, many single men and women actually hope to use the app to support their lifestyle. When, during the upcoming Chinese New Year, parents start nagging about when they will settle down, and warn that they might otherwise die alone, they can now reply that they’ve already got an app for that.

🔹 What’s in a Name?

Over the past few days, much of the discussion has centered on the app’s name, which is what drew attention to it in the first place. As interest in the app surged, fueled by international media coverage, criticism of the name also grew. Some found it too blunt, while public commentators such as Hu Xijin openly suggested that it be changed.

Considering that the mention of death itself carries online sensitivities in China, it’s possible that there’s been some criticism from internet regulators, and the Ele.me platform also might not be too pleased with the name’s resemblance.

Whatever the exact reasons, the app’s creators announced on January 13 that they would abandon the original name and rebrand the app as its international name ‘Demumu’ (De derived from death, the rest intentionally sounds like ‘Labubu’).

This marked a notable shift in stance: just two days earlier, one of the app’s creators had stated that they had not received any formal requests from authorities to change the name and had shown no apparent intention of doing so.

Most commenters felt that without the original name, the app doesn’t make sense. “As young people, we don’t care so much about taboo words,” one commenter wrote: “Without this name, the app’s hype will be over.”

On January 14, the creators then made another U-turn and invited app users to think of a new name themselves, rewarding the first user who proposes the chosen name with a 666 yuan reward ($95).

The naming hurdles suggest the makers are quite overwhelmed by all the attention. At the same time, dozens of competing apps have already appeared. One of them, launched just a day after Are You Dead Yet? went viral, is “Are You Still Alive?” (活了么), which offers similar basic functions but is free.

This new wave of similar apps has also led more people to wonder how effective these tools really are once the quirkiness wears off. One Weibo blogger wrote:

💬 “I really don’t understand why this app went viral. You can only check in daily, and you need to miss two consecutive check-in days for the emergency contact to be alerted. That means, if something actually happens, someone will only come after three days!! You’ll be rotting away in your home!!”

Others also suggested that it is clear the app was designed by younger people—the elderly users who might need it most would likely forget to check in on a daily basis.

🔹 Why “Dead Yet?” Is Like Viagra for a Pressured Generation

Amid the flood of Chinese media coverage, one commentary by the Chinese media platform Yicai7 stands out for pinpointing what truly lies behind the app’s popularity.

The author of the piece “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Dead Yet’ App” (in Chinese) argues that the app did not win users over because of its practical utility. Its main users are young people for whom premature death is an extremely low-probability event. They are clearly not downloading the app because they genuinely fear that “no one would know if they died,” nor are they likely to check in daily for such a tiny risk.

Since the app is clearly being embraced by users that do not belong to the actual target group, it must be providing some unexpected value.

💊 The author compares this unplanned function of the app to how Viagra was originally developed to treat heart disease. In this case, app users say that interacting with Dead Yet? feels like a lighthearted joke shared between close friends, offering a sense of social empathy and emotional release in a way that does not feel pressured.

Because the pressure—that’s the problem. Yicai describes just how multidimensional the pressures facing many young adults in China today can be: there is the economic challenge of the never-ending rat race dubbed “involution” along with uncertainty in the job market; there’s the “996” extreme work culture across various industries, leaving little room for private life; traditional family expectations that clash with housing and childcare costs that many find unattainable; and the world of WeChat and other social media, which can further intensify peer pressure and anxiety.

Of course, a lot has been written about these issues through the years. But do people really get it?

According to Yicai, there’s not enough understanding or support for the kinds of challenges young people face in China today. Even worse, older generations’ own past experiences often impose additional burdens on younger people, who keep running up against traditional notions while receiving inadequate support in areas such as education, employment, housing, marriage, family life, and even healthcare.

The author describes the unexpected viral success of Dead Yet? as a mirror with a message:

💬 “The viral popularity of ‘Are You Dead?’ seems like a darkly humorous social metaphor, reminding us to pay attention to the living conditions and inner worlds of today’s youth. For the young people downloading the app, what they need clearly isn’t a functional safety application, it’s a signal that what they really need is to be seen and to be understood—a warm embrace from society.”

Will the Dead Yet? app survive its name change? Is there a future for Demumu, or whatever it will end up being called? As it is now—the basic app with check-in and email or SMS functions—it might not keep thriving beyond the hype. If it doesn’t, it has at least already fulfilled an important function: showing us that in a highly digitalized, stressful, and often isolating society where AI and social media play an increasingly major role, many people yearn for the simple reassurance of being noticed, mixed with a shared delight in dark humor. Just a little light to shine on us, to remind us that we’re not dead yet.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Thanks to Ruixin Zhang & Miranda Barnes for additional research

1 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2013. “Living Alone in China: Historical Trends, Spatial Distribution, and Determinants.”

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Living-Alone-in-China-%3A-Historical-trend-%2C-Spatial-Yeung-Cheung/8df22ddeb54258d893ad4702124066b241bbdf8d.

2 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2015. “Temporal-Spatial Patterns of One-Person Households in China, 1982–2005.” Demographic Research 32: 1103–1134.

3 Li Jinlei (李金磊). 2022. “China’s One-Person Households Exceed 125 Million: Why Are More People Living Alone?”[中国新观察|中国一人户数量超1.25亿!独居者为何越来越多?]. China News Service (中国新闻网), January 14, 2022. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cj/2022/01-14/9652147.shtml (accessed January 13, 2026).

4 Danan Gu, Qiushi Feng, and Wei-Jun Jean Yeung. 2019. “Reciprocal Dynamics of Solo Living and Health Among Older Adults in Contemporary China.”

The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 74 (8): 1441–1452. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby140.

5 Wang Fang (王方). 2026. “‘How We Went Viral: The Founder of the ‘Dead Yet?’ App Speaks Out’” [‘死了么’创始人亲述:我们是如何爆红的]. Pencil Way (铅笔道), interview with Guo (郭先生), published via 36Kr (36氪), January 13, 2026. https://www.36kr.com/p/3637294130922754 (accessed January 13, 2026).

6 Lü Qian (吕倩). 2026. “‘Am I Dead?’ App Price Raised from 1 Yuan to 8 Yuan, Previously Removed from Apple App Store Rankings Multiple Times”

[‘死了么从一元涨至八元,曾被苹果AppStore多次清榜’]. Diyi Caijing (第一财经), January 11, 2026. https://www.yicai.com/news/102997938.html (accessed January 14, 2026).

7 First Financial/Yicai (第一财经). 2026. “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Am I Dead?’ App: Young People Need a Hug” [‘死了么爆火背后,年轻人需要一个拥抱’]. Official account article, January 12, 2026. https://www.toutiao.com/article/7594671238464569899/ (accessed January 14, 2026).

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment6 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment6 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West