Featured

Op-Ed: Your Use of “Netizen” Hurts Responsible China Coverage

It’s not innocent jargon. Not anymore.

Published

8 years agoon

Far from innocent jargon, the word ‘netizen’ has political implications in its use today and should not be casually tossed around, says Beijing-based journalist Dave Yin. In this op-ed contribution, Yin responds to our recent article “Netizens or Not?“

It’s unlikely that when internet theorist and author Michael F. Hauben coined the word “netizen” more than thirty years ago, he would have imagined that, one day, on the other side of the world, a few handfuls of Western reporters and media critics covering China would be divided: in one camp applauding and in the other cursing his creation. It’s equally unlikely he’d recognize at first glance what his word has come to mean in 2018 – and to whom.

Common thought is that whether or not “netizen” should be used, and what it means, are at the heart of this debate, which by now spans publications both big and small, free and censored. It hasn’t gotten us anywhere.

But in view of China’s escalation of online policing and digital surveillance, the concept of “netizen” is evolving, as must its coverage in Western media. Far from innocent jargon, the word today has political implications and a growing potential for harm, one Western media must recognize if it is to conduct responsible reporting.

A Western interpretation

When considering the word “netizen,” it helps to know what one is talking about. Namely, pick a definition, and stick with it.

Scenario A)

One clear-cut definition offered by the Atlantic designates a unique identity; young, wealthy, educated Chinese urbanites and/or politically active individuals in online communities adept at skirting censorship.

Here, simple protocol applies. Writers using “netizen” must first make sure the subjects of their story actually match this description. Then, they must assess whether these complex socioeconomic and political elements are evident in this word. Hint: they’re not. Inevitably, writers should be explaining these elements to accompany the use of this term in each article it appears in. Anything short of this is incomplete reporting.

Scenario B)

If broadly defined to be a synonym to “Chinese internet users,” as is more often the case, then several questions emerge: Why do Chinese internet users need a special label in the first place? Why is “Chinese internet user” inadequate when this type of terminology works for everyone else? If research (paywall) suggests the online habits of Chinese are similar to the rest of us, what are we trying to accomplish by othering them?

Self-applied labels

In advocacy reporting, we try to respect a person’s self-applied labels, such as with race or sexual orientation, so I appreciate the irony when I say that just because Chinese people call themselves “netizens” doesn’t necessarily mean we should.

Be it when describing race, sexual orientation, disability, etc. there is a general effort to use terminology that centers the person, and not the circumstance, which is often complex. “Person with impaired vision,” “a cisgender gay man,” “the woman, who identifies as a second-generation Filipino immigrant,” “individuals claiming to be members of the Anonymous collective” are infinitely better than “the blind,” “the gay,” “the Filipino,” “Anonymous.” In pieces where nuance and individuals matter, these words do more than fill up space.

“Netizen,” as it is currently used, erases both.

What’s more, these often political labels emerged in societies with freedom of association where one makes a statement simply by publicly identifying. By contrast, what does it mean to label yourself with something as vague and abstract as “netizen” in a society that doesn’t allow such freedom, and what effect does it have when Western media take up this cause?

A Chinese strategy

The self-applied label argument is also unsound when you consider that “netizen” is actually a mistranslation of the word “wǎngmín” (网民).

In wǎngmín 人民 (people), nóngmín 农民 (farmer), jūmín 居民 (resident), yímín 移民 (migrant), yúmín 渔民 (fisherman), and míngē 民歌 (folk song), “mín” 民 simply means “people,” without any “citizen” connotation, and therefore “wǎngmín” 网民 really just means “internet people/people on the internet.”

In other words, “netizen” and “wǎngmín” are faux amis. It’s a mistake that Western media has allowed to proliferate and one that we must now contend with.

While the use of the English word by ordinary Chinese and private Chinese media could boil down to guileless ignorance towards English nuance, by contrast, “wǎngmín,” when applied by the Chinese government and its mouthpieces, is part of deliberate national policy. As described by Manya Koetse in her analysis, the Chinese term is an official category of Chinese nationals on which the CCP imposes severe restrictions.

What ramifications are there for Western media in not consciously decoupling these wildly different interpretations by different actors? By casually tossing the word around, do we not run the risk of normalizing Chinese internet policy?

While we, working in the Far East, may feel at times that our work is isolated, it should be noted that people are, in fact, reading, for better or worse.

“[‘Netizen’] has been used when reporting on China for a decade+ [sic] in order to relieve journalists of understanding what they’re reporting on,” one Reddit user (Western netizen?) writes. “Today it is a lazy way to assume all internet users in China think the same way by f*cking lazy journalists.”

“Netizen” may well stick around. China’s emerging digital policies have all but ensured it. But we owe it to our readers and the people we cover to get with the program, to evolve our terminology and critical judgment at the same pace as the subject matter.

We need to understand that the benefits of its selective, judicious use, as a result of explicit purpose, come from highlighting and decoding China’s socioeconomic and political situation, not from generalizing 772 million individuals, and least of all from othering them or normalizing their constraints. It may help everyone’s understanding of this country, including our own.

By Dave Yin

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

Spring Festival Trend Watch: Gala Highlights, Small-City Travel, and the Mazu Ritual Controversy

Some stories going viral during the holiday season seem to exist in a recurring social cycle of their own.

Published

5 days agoon

February 22, 2026

🔥 China Trend Watch (week 8 | 2026) Part of Eye on Digital China by Manya Koetse, China Trend Watch is an overview of what’s trending and being discussed on Chinese social media. The previous newsletter was a chapter dive into the story of China’s latest hospital scandal. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

One Shanghai woman was so disappointed by what her boyfriend’s parents served for Chinese New Year that she ended the relationship over it.

The 26-year-old, who described her own family background as “pretty good,” shared her experience on social media. She said she had already known that her new handsome boyfriend came from a lower-income family. But after traveling to his hometown in Jiangxi for the Spring Festival and seeing what his mother had prepared for the New Year’s dinner, she was so shaken that she immediately booked a train ticket back to Shanghai.

Here is a screenshot of her post and the picture of the dinner she posted:

This is actually a story that exploded on Chinese social media back in 2016, and its virality is quite typical of the period surrounding Chinese New Year — it is always a very special time when it comes to the kinds of trends that unfold.

It often feels as though stories simmering in the background suddenly boil over during the holiday season. Digital shifts become more visible, cultural traditions take on new meanings, consumer hypes mushroom across the country, and seemingly insignificant social topics can grow enormous: a road rage incident, a noteworthy TV moment, or that one family’s New Year’s dinner.

What’s perhaps most striking is that the story of that Shanghai woman (who really did break up with her boyfriend after that dinner) could have easily been a trending topic during this year’s Spring Festival, and she would likely face the same backlash today (people found her disrespectful and snobbish). In fact, some stories that went viral during the holiday season years ago still resurface today, as if they exist in a recurring social cycle of their own.

Take the nagging questions from family and nosy neighbors about why the single sons & daughters returning to their hometowns for the New Year are still not married, for example; it’s a topic that somehow comes up every Spring Festival. The pressure caused by these “interrogations” have led some single people to rent a boyfriend or girlfriend to bring home to meet the parents — a story covered by the media for years.

People still “rent a partner” to avoid another year of awkward questions about their (non-existent) love life. What has changed is the price. Ten years ago, one could rent a boyfriend or girlfriend for about 500 yuan (around $75). This week, social media reports suggested that these so-called “life actors” (生活演员) — who rent out their services as a pretend partners — now charge up to 3,000 yuan per day (about $435) (#深圳除夕当天租男友3000元一天#).

All of this unfolds because so much happens around Chinese New Year (春节 Chūnjié) at once. While China is transforming rapidly, some things remain remarkably consistent. The holiday is not just a peak moment for consumer culture and travel, it is also the year’s major moment for the box office and for China’s largest live televised event, the Spring Festival Gala, which reflects what matters not only to commercial sponsors but especially to the Communist Party. At the same time, it is a period of family reunions and homecomings for those who may not have other chances during the year to visit their hometowns.

From living rooms to long train rides, from fear-of-missing-out to social media memes, from pressures and expectations to fun and traditions, this period offers a concentrated snapshot of China’s current momentum, revealing social anxieties, political priorities, and pop culture obsessions all at once.

Let’s dive into some of the other trends that have been especially noteworthy during this year’s Spring Festival.

Quick Scroll

-

- 🧊 China’s short track speed skating, historically one of China’s strongest Olympic teams, has exited the 2026 Milan Olympics with what’s called “the worst results in 28 years.”

- 🥇 Meanwhile, the gold medals for Xu Mengtao (徐梦桃) & Wang Xindi (王心迪) in freestyle ski aerials, Su Yiming (苏翊鸣) in snowboard slopestyle, and Ning Zhongyan (宁忠岩) in 1500m speed skating were widely celebrated online.

- 🇺🇸 The much-discussed Trump–Xi meeting has been confirmed for late March, scheduled from March 31 to April 2. Trump’s planned trip will mark the first U.S. presidential visit to China since his own 2017 visit.

- 🍿 China’s 2026 Spring Festival box office has surpassed the 4 billion yuan (US$550 million) mark. The February 15–23 holiday window — one of the most important periods for the Chinese film market — saw racing comedy Pegasus 3 (飞驰人生3) top the charts this year.

- 🎬 One article called it the “hell yeah!” movie of the year. Blades of the Guardians (镖人) by Xu Xianzhe (许先哲) is the hardcore martial arts film that outperformed its opening-day numbers and became an audience favorite.

- 🏮 Beijing’s Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace) has become a viral hit for its 4.6 km illuminated route with thousands of lanterns lighting up at 17:30 each evening.

- 🌕 Less popular: yellow lanterns used for New Year decorations in various cities triggered criticism online for looking “unfestive” or even representing “mourning colors,” leading local authorities to order a swap back to traditional red after the backlash.

- 🕯️ Two explosions in Jiangsu and Hubei brought the total number of deaths from fireworks-related incidents for the first week of the 2026 Spring Festival holiday to at least 20.

What Really Stood Out This Week

The Highlights of the 2026 Spring Festival Gala

Earlier this week, the 44th edition of the China Media Group Spring Festival Gala took place (see our liveblog of the entire show here). At its peak, an estimated 400 million people were simultaneously watching the 4.5-hour show, which, as usual, contained a variety of performances ranging from dance and song to comedy and acrobatics.

So, what was different this year?

In case you’re not an avid watcher of the Gala—which I fully get—let’s get one thing straight first: the show overall is highly predictable and follows comparable year-on-year patterns. There is always a performance featuring different ethnicities; besides the mainland entertainment elite, there must be a variety of older and younger singers from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macao; there is a military song; there is a traditional opera element; and there is always a comic skit that everyone finds cringeworthy. In these respects, 2026 was right on track with previous years.

However, there were definitely some noteworthy aspects to this year’s Gala. Some are significant because they mark a subtle, broader shift, while others are more obvious.

✦ First, the theme. The show was titled “Galloping Steeds, Unstoppable Force” (骐骥驰骋 势不可挡). Every year has a theme, often nodding to the zodiac sign and usually focusing on messaging such as “a thriving nation,” “reunion,” or, as in 2020, “Together Realizing the Moderately Prosperous Dream.” This year’s theme felt less modest, aligning with a larger narrative about China’s role on the world stage today as an “unstoppable force.”

✦ The role of the director. The influence of the show’s director seems to have been somewhat overlooked in coverage of the Gala. Yu Lei (于蕾, b. 1979) is not only the first female director in the show’s 44-year history but also the first to lead the production for four consecutive years. As chief director, Yu Lei has established a very identifiable aesthetic framework, perfecting a style of show that merges Chinese tradition with high technology. Outstanding examples of this include the beautiful and innovative 2024 “Koi Carp” (锦鲤) dance, and the 2022 “painting” dance “Only This Green” (只此青绿) inspired by a famous Chinese handscroll.

This year featured even more segments blending traditional inspiration with state-of-the-art technology, from the creative “Celebrating the Flower Goddess” (贺花神, watch here) to the Xinjiang Dance Troupe’s “Silk Road Ancient Rhymes” (丝路古韵, watch) and dancer Zhang Han’s beautiful performance of “Chasing Shadows” (追影) (link).

These performances align with the broader Guochao (国潮) trend—literally “national trend”—and the promotion of traditional culture seen over the past years. Under Yu Lei’s guidance, this cultural pride is fused with technological innovation to create a new kind of Chinese aesthetic that is indeed “unstoppable.” If we don’t recognize this as the trend of today, it will certainly be the new normal of tomorrow.

✦ Then the global outreach. This is the first time I’ve seen the show so deliberately cater to foreign audiences. A promo added to the YouTube livestream explicitly stated: “This is where it gets cool, this is where the future meets timeless Eastern aesthetics. This is where we feel warmth, where everyone belongs. When the CMG Spring Festival Gala begins, you are coming home.”

This past year was a turning point where China became “cool” among younger Western audiences (see my piece on Becoming Chinese) — this soft-power effect is being fully embraced by Chinese state media, and the Gala is part of this. Beijing is increasingly positioning the event as a global celebration rather than just a national one, which explains the inclusion of more foreign performers—from Lionel Richie and John Legend to Hélène Rollès, Westlife, the Hungarian National Folk Ensemble, Spanish dancer Jesús Carmona, and the Austrian acrobatic troupe Jonglissimo.

✦ Lastly, AI and robotics. Perhaps the most obvious shift was the heavy use of AI and robotics, which became a major talking point on X and in foreign media. While the Gala has already incorporated robots for two decades (!), this year marked the first time they participated across almost every genre, from dance and comedy sketches to martial arts and short films.

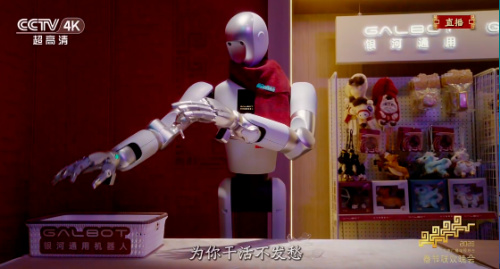

The abundance of robots was driven by a historical first: four domestic humanoid robot companies—Unitree Robotics (宇树科技), Noetix Robotics (松延动力), MagicLab (魔法原子), and Galbot (银河通用)—all appeared as official corporate partners. We also saw the world’s first martial arts performance by a fully autonomous humanoid robot cluster.

Although the robots were a highlight, they were also a point of online critique for being a bit “overdone.” Judging by social media comments, many viewers still preferred the classic, iconic performers—like pop superstar Faye Wong (王菲) or the legendary comedian Cai Ming (蔡明), who has performed at the Gala for decades.

So despite all the new technological developments and the clear look into the future, audiences still seemed to love the performances that leaned toward the past, highlighting a bit of a ‘battle’ between innovation and nostalgia.

The Travel Trends to Know

There are two moments in the year that are the major travel periods for China, reflecting the current trends of the tourism industry: the National Day holiday and the Spring Festival holiday. These periods usually reveal trends that were either simmering and have now expanded, or upcoming trends surfacing for the first time.

Some things don’t really change, such as cities like Beijing, Chengdu, Chongqing, and Shanghai being among the most popular domestic destinations. (As for international locations, Seoul, Bangkok, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Ho Chi Minh City, and Bali top those lists).

These are some noticeable trends for this moment:

✦ A big love for small cities has been noticeable among China’s younger travelers recently. This is a different trend from what used to be the post-Covid “special forces travel” (特种兵), which was the kind of tourism where travelers would do as much as possible within a short time and limited budget, almost like crossing destinations off a bingo card.

Now, travelers are turning more to “hidden gems” or what have been called “dark horse destinations” in Chinese media (黑马目的地). The goal is not just to cross them off a list, but to slow down and experience local culture. Folk culture, markets, and arts & crafts have seen a rise in popularity.

Some examples are Jieyang and Chaozhou which, together with Shantou, lie in eastern Guangdong. Some of these places are seeing the fastest tourism growth rates in the entire country, thanks to strong local folk customs and food culture, with people preferring homestays or Airbnb-style holiday rentals for an authentic, local experience.

Cities like Jingdezhen, Kaifeng, Quanzhou, and Zigong—all previously not particularly known as top destinations—are also new “breakout” cities this season.

Another example is Chongzuo in Guangxi, located along the China–Vietnam border, with its Zhuang ethnic minority culture, karst mountains, rivers, and rural scenery.

All of this represents a big shift in China’s domestic tourism industry, offering new experiences to Chinese travelers while also boosting the local economies of these places.

While these new destinations all sound lovely and peaceful, posts on Xiaohongshu show that the viral nature of these “hidden gems” have also caused them to be exceptionally busy during this season.

✦ Reverse Spring Festival (反向过年) has been a trend for several years, but it has been especially prominent this year. It is the trend where, instead of children traveling from big cities to visit parents in their hometowns, the parents are coming to celebrate the New Year with their kids in medium-sized or larger cities. This has also led to the rising popularity of Guangzhou as a Spring Festival destination.

What you also see are families all traveling together to a third location outside of both their hometowns and work-based cities.

✦ “Going the opposite way” is also a popular travel trend that has particularly emerged this year, with people from China’s south traveling to the north and people from the north traveling to the south—one group seeking an experience of ice and snow, while the other wants warmth and sunshine.

The locations that stand out for this are Harbin in the north, with its Harbin Ice and Snow World (哈尔滨冰雪大世界) holding a spot in the national top-ten scenic spots (although, unfortunately, Harbin has seen rising temperatures this winter, leading to melting snowmen).

The tourists from the south who come to visit Habrin are nicknamed “Little Southern Potatoes” (南方小土豆) for being all bundled up in brand-new puffy coats.

In the south, Yunnan’s Kunming has seen a surge in popularity, along with Lijiang, Xishuangbanna, and Dali, which all saw a drastic increase in bookings.

Especially Noteworthy Online Discussions

Door-to-door Pet Sitting as Emerging Business Model

✦ During China’s 2026 Spring Festival travel rush, a specific phenomenon gained traction on Chinese social media in this pet-loving era: “door-to-door pet-sitting” (上门喂宠). This emerged as one of the holiday’s most surprisingly profitable side gigs after Shanghai pet sitter Huan Cong (桓聪) told Jiupai News (九派新闻) that his five-person team would complete some 2,000 jobs within the twenty-day holiday period, with an expected revenue of 160,000 yuan ($22,120).

Huan is not the only one profiting from this lucrative business—pet sitters across the country are cashing in during the Spring Festival. This trending story reflects the massive scale of China’s pet economy, an industry growing year-on-year as those born in the post-90s and post-00s now comprise the majority of pet owners.

At the same time, digging a bit deeper reveals the reality behind the trend. While relatively lucrative, the work is tiresome; Huan sometimes visits 55 households in a single day to ensure he and his team can feed all their customers’ dogs and cats. It might be good business, but it’s certainly not easy.

An Unusually Bad Karma Story

✦ One story that has been especially noteworthy this week involves a religious ceremony dedicated to honoring the Chinese sea goddess Mazu (妈祖). A protector of fishermen and sailors, Mazu has millions of worshippers in eastern and southeastern parts of the Chinese mainland and Taiwan; regions where people have traditionally relied on the ocean for their livelihoods.

On February 18, the second day of the Chinese New Year, something unusual happened during the annual Mazu procession in Shishi Village (拾石村) in Zhanjiang, Guangdong province.

A unique local tradition involves the divine selection of a Mazu “messenger,” a child believed to serve as a vessel for the goddess’s spirit during the procession. This is decided through the ritual of shèngbēi (圣杯) throws or “divination cup” tosses: children throw crescent-shaped wooden blocks, and based on how they land, the child believed to have the closest connection to Mazu is selected to take the place of the statue during the parade.

For the past eight years, the same girl, now 14 years old, had reportedly been selected as the spirit medium through this sacred ritual.

However, this year, a wealthy businessman surnamed Xu (许)—the financial sponsor of the procession—suddenly replaced the chosen girl with his own son. That is where things started going wrong.

According to local reports, the boy seemed unfamiliar with ceremony protocols. He misaligned offerings on the ritual table, stood in the wrong position at the start of the procession, and accidentally stepped on a ritual spot reserved for divine generals, which living participants are forbidden from entering.

Most importantly, the shèngbēi ritual, in which the boy had to seek Mazu’s approval through the blocks, kept giving the same negative result (nùbēi 怒杯) for no less than eight consecutive times. There are three possible outcomes, and the statistical chance of throwing the same negative result eight times in a row was seen as a sign of extreme divine disapproval. People were eventually too afraid to let the boy try a ninth time.

As a result, with no “green light” from Mazu, the bearers of the sedan chair needed for the procession refused to lift it, and the entire ritual halted.

Seeing no other choice, organizers got the girl to come back. Upon her first shèngbēi throw, a valid result was immediately obtained and the sedan chair was reportedly lifted without any difficulties. The procession then proceeded with both children riding the sedan chair together (which also prompted criticism from locals for being a further deviation from tradition). After the procession concluded, the girl was visibly distressed.

As this story has gone viral, many see it as a sign that wealth cannot buy a way into a sacred ritual—the gods simply do not agree, and money cannot buy everything.

Consequently, Mazu and the shèngbēi ritual have unexpectedly become hot topics.

The actress Liu Tao (刘涛), who once played Mazu in a popular television drama, has resurfaced as a “lucky meme” during this holiday. Liu Tao’s relationship to Mazu goes beyond just her role in the series. During the filming, she allegedly also went to the temple and performed the traditional divination ritual and got three positive throws in a row, which was seen as a positive omen for her taking the role.

She’s become a celebrity ambassador for Mazu culture, something that is now highlighted by netizens as the Shishi Village story trends. People have begun using Liu Tao’s image as Mazu as an auspicious phone wallpaper.

The irony, of course, is that the Xu family spent a fortune trying to force Mazu’s blessing, while millions of ordinary netizens are now getting their “lucky fix” for free through their Liu Tao meme. How very “Spring Festival” is that? 🏮

—That’s a wrap. Many thanks to Ruixin Zhang and Miranda Barnes for their input on this newsletter, and for managing to watch the full 4.5 hours of the Spring Festival Gala together with me!

I’m taking a few days off now for some travel, but expect to be back with a new trend newsletter for you next weekend.

See you next edition.

Best,

Manya

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo. Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. If you no longer wish to receive these newsletters, or are receiving duplicate editions, you can unsubscribe at any time.

Chinese New Year

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

Watch the CGM Spring Festival Gala with us. It’s that special annual evening show that captures millions of viewers on the night of the Chinese New Year. Loved by many, hated by some, it always generates social media buzz.

Published

2 weeks agoon

February 16, 2026

Watch the CGM Spring Festival Gala with us. It’s that special annual evening show that captures millions of viewers on the night of the Chinese New Year. Loved by many, hated by some, it always generates social media buzz. We’ll bring you the ins & outs of the 2026 Gala and its social media frenzy, with updates before, during, and after the show.

It is time again for the China Media Group Spring Festival gala – better known as the ‘Chunwan’ (春晚) – one of China’s most significant televised cultural events of the year, organized and produced by the state-run CCTV since 1983 and broadcast across dozens of channels, watched by millions.

What can we expect a typical Chunwan to look like? The programme usually runs for about four hours, from 20:00 China Standard Time to a little past midnight, and features around 30 acts: acrobatics, singing, dance, comic sketches (xiaopin 小品), crosstalk (xiangsheng 相声), magic, Peking Opera, public service segments, and tributes to national heroes. This year, however, some things will be different — more on that soon.

Liveblogging the show has become something of a personal tradition. You can explore more of my Gala coverage on the website here, spanning the past ten years, during which I liveblogged eight editions.

Tonight, I’m watching the Gala together with Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang, so follow along in the liveblog below. Keep the page open and you should hear a ping when new updates arrive.

Update: This liveblog is now closed. You can still read all updates below, sorted from oldest to newest.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 19:06

About an hour to go — about the final version of the program

As we’re waiting for the event to kick off, a little bit about the show’s background. Because it’s not just the Gala night itself that has become a tradition, both online and offline, but also the discussions and buzz surrounding it.

As every year, the final version of the programme is only released quite last-minute, even though the full show — behind the scenes — has already gone through multiple rehearsals and generated plenty of anticipation.

There is likely some risk calculation behind this, as things can still change at the last minute. But the element of surprise in the final performance lineup also adds to the excitement and helps boost viewership, with discussions over who will perform what continuing well into the evening as the show begins.

The full program is typically distributed by China Media Group (CMG) as an extremely long, scrollable image designed for phone viewing, which also makes it a bit harder to copy and paste (though easier in the AI era).

By the way, CMG, the main organizer of the Gala, is an umbrella media powerhouse that includes the national television broadcaster China Central Television (CCTV), the national radio network China National Radio (CNR), and international broadcaster China Radio International (CRI).

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 19:35

What can we expect to stand out at this 2026 CMG Gala?

Half an hour to go. There are a few things that already stand out about this year’s Gala — the 44th edition — even before it has begun. Three short observations:

1– Especially AI & Tech-focused

The Gala has traditionally been a blend of culture, commerce, and politics, with Party-state ideology woven into popular entertainment, from aesthetics to messaging, including through skits. Over the past decade, the Gala has increasingly focused on showcasing China’s technological power. I often think back to that iconic 2016 performance featuring 540 dancing robots, which helped set the stage for the Gala as an annual showcase of robotics and other state-backed media technology.

This year, with China’s AI stronger than ever and ByteDance’s Seedance 2.0 among the major talking points, we will likely see technology everywhere. There will be AI-generated imagery responding to stage elements in real time, hyper-realistic digital humans, and more.

Robots are also still very present. The Gala reportedly features its largest robot lineup to date, including dancing humanoid robots from Unitree Robotics (宇树科技) and other companies. Some martial arts segments are also expected to feature robot participation.

2– Foreign-focused

Following the Year of the Snake (2025) — when China became “cool” (see my piece on Becoming Chinese) — this soft-power effect is being fully embraced by Chinese state media. The Gala is now promoted internationally, including on YouTube, with messaging such as: “This is where it gets cool, this is where the future meets timeless Eastern aesthetics. This is where we feel warmth, where everyone belongs. When the CMG Spring Festival Gala begins, you are coming home.”

This outward-facing promotion also aligns with the Spring Festival being added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list in late 2024. Beijing is increasingly positioning the event as a global celebration rather than only a national one.

The participation of Lionel Richie is particularly noteworthy. Together with John Legend, Jackie Chan, and others, he will perform in what is expected to be the most international segment of the night, highlighting China’s global cultural appeal. The performance will be staged from Yiwu, China’s wholesale capital, which produces an estimated 60–80% of the world’s Christmas decorations, among many other goods.

Other international performers appearing tonight include John Legend, Hélène Rollès, Westlife, the Hungarian National Folk Ensemble, Spanish dancer Jesús Carmona, and Austrian acrobatic troupe Jonglissimo.

3 – Taiwan

Lastly, Taiwan-related performances will inevitably carry political significance, especially given current cross-strait tensions. There is a strong sense of cultural nostalgia in the programme, emphasizing connection and shared heritage. For example, in the song “Treasure Island Love Song” (宝岛恋歌), with “Treasure Island” being an affectionate term for Taiwan may become the clearest expression of this theme. Will let you know when it comes up!

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 20:02

Instant Magic

Ok, we’re kicking off with instant magic. That’s the name of this opening song in English, but its Chinese name is 马上有奇迹, which means “there will immediately be a miracle”, but since “immediately” also means “on horseback” there’s a double meaning (“On the horse, there are miracles.”) There are a lot of word jokes this Year of the Horse, and they’re all meant to be both funny and lucky at the same time.

A little more context for tonight’s show: it is clearly horse-themed as we welcome the Year of the Horse, and carries the title “Galloping Steeds, Unstoppable Momentum” (骐骥驰骋 势不可挡). The title itself feels meaningful. In previous years, themes were often more closely tied to tradition, family, fulfilling dreams, and cherishing reunion, while the emphasis on speed this year seems to signal China’s rapid rise and growing global influence — at least, that’s how I read the idea of “unstoppable momentum.”

The show is directed by Yu Lei (于蕾), who has long been associated with the Gala and is now directing it for a fourth consecutive year, that’s a first in the Gala’s 44-year history.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 20:08

Different venues

We’re now seeing a showcase of all the different venues participating tonight. The main show is broadcast from Beijing, but there are always multiple venues outside of Beijing. This year:

• Harbin (ice-themed stage)

• Yiwu (Global Digital Trade Center, international performers)

• Hefei

• Yibin (“First City on the Yangtze” skyline)

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 20:10

Start of Spring

We’re watching the “Start of Spring”: the gala’s first major song-and-dance stage, featuring an all-female ensemble with AR technology enhancing the theme of the start of the Chinese New Year.

The performers come from mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, combining some more famous older faces with newer mainland performers.

A little note: this Gala is broadcast on all kinds of channels and platforms, including on BiliBili – which is where the youth is. The Gala has lost a lot of younger viewers, so this is one way to try and reach the audiences who are less used to watching traditional tv. This will be the second year Bilibili and the Chunwan are cooperating for the live broadcast, also allowing for “bullet comments” that appear in the screen.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 20:18

Grandma’s Favorite

This is the first comedy sketch of the night, featuring Cai Ming (蔡明), the beloved 64-year-old comedy veteran.

This sketch is much-awaited! Not only because of Cai Ming herself, but also because of the theme. In 1996, the famous actress also did a sketch featuring a robot (机器人趣话)- or actually, it was she herself who played a robot wife.

Now, after 30 years, she again returned, and this time not just meeting robots in the new AI era, there is also another robot version of herself.

The robots are by the Beijing-based humanoid robotics startup Songyan Power (松延动力/Noetix Robotics), and in this sketch, they are portrayed as taking care of the elderly – washing her clothes and doing other chores, while also keeping her company – because her own grandchild won’t visit her.

The sketch is a comedy one, obviously, but (as every year), there are always young people on social media who struggle to find it particularly funny.

Regardless, the sketch touches upon some important social issues in a rapidly aging China, perhaps seeing a future where more elderly will use tech and AI.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 20:29

武BOT — Martial Arts Robots

Quite amazing, this performance featuring robots by the Hangzhou-based humanoid robotics company Unitree Technology (宇树科技) doing actual martial arts together with students from the Henan Tagou Martial Arts School.

Turning this into a robot vs human battle, it’s really quite Bruce Lee goes 2026, and an excellent showcase for Unitree Tech and China’s AI robot development at large.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 20:34

Made in China

Made in China, created in China – a song is about futuristic made-in-China inventions that are now in people’s daily lives.

The English name of this song is “Smart Creation of the Future” (智造未来), featuring many popular male singers: Jordan Chan/Chen Xiaochun (陈小春), Jerry Yan/Yan Chengxu (言承旭), Luo Jiahao (罗嘉豪), Jackson Yee/Yi Yangqianxi (易烊千玺), performing together wih Magic Atom (魔法原子, another Chinese robotics company. (One of the four companies, if I’m correct, that is participating in this year’s Gala).

🕒 Feb 16, 20:38

Celebrating the Flower Goddess

Lovely segment featuring many special technologies and showing that Chinese traditional culture and modern technologies can blend together. This is in line with show elements that we’ve seen over the past few years, especially in the Gala’s directed by Yu Lei.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 20:44

Dazzle and Move

This segment, featuring Aaron Kwok/Guo Fucheng (郭富城, born 1965) and Wang Yibo (王一博, born 1997), has been among some of the songs that have been highly anticipated online, mostly due to the millions of fans these super popular singers/popstars have among both older and younger audiences.

Wang Yibo’s outfit (a Saiid Kobeisy 2026 spring/summer couture feather-embroidered jacket) leaked hours before broadcast and immediately went viral. Netizens are framing it as a “passing of the torch” moment between two generations of Chinese stage performers.

🕒 Feb 16, 20:49

Once a viral word hits the Gala, it’s officially “washed”

The gala always features internet hit words and slang that people have forgotten about throughout the year. But because they use the slang awkwardly, according to many young viewers, it gives off the impression of a traditional show trying too hard to fit into to online life.

One meme posted shows the ““The Life Cycle of an Internet Meme/Slang””: a new meme appears, it’s fresh and funny, then it suddenly goes viral, and then when your co-workers and parents start using it, it’s basically dead.

However, when it then finally appears in the Gala, it’s officially over, and the meme is “washed.”

Some netizens are counting the number of “slang words” used by the Gala that can now (tongue-in-cheek) be removed from the popular online lexicon.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 20:55

Whose Dish?

We’ve arrived at the stand-up segment, which is interesting — traditionally, xiangsheng (相声) acts on the Gala tend to come from the north, while these two performers have a strong southern (Hunan) accent.

The Gala’s comedy shows have long been criticized for being too northern China–centric, with many viewers in the south, especially in Cantonese-speaking regions, feeling less connected to them. This shift may reflect an effort to strike a better balance between northern and southern comedy traditions.

By the way, the performers are Xu Haolun (徐浩伦) and Tan Xiangwen (谭湘文).

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 21:18

Sorry for some tech problems > Back now

Back online! Had some tech problems, so missed the last performance, but we’re back. Watching “Lucky Steed” (吉量), featuring singer Zhou Shen (周深). The kids come from Guizhou, doing a fashion show featuring their local traditional costumes.

They’re part of the ‘Village T-stage’ (村T) of Southeast Guizhou, which is a grassroots fashion troupe. You could spot traditional attire of the Miao, Dong, Buyi, Sui, and Yao peoples. The Gala has always placed a heavy focus on ethnic and regional representation (emphasizing national unity and ethnic solidarity), and there will be more songs later on showing this.

What did we miss?

1. There was one segment shown from Yibin (宜宾) one of the four venues besides Beijing for the 2026 Gala, chosen to showcase Sichuan’s cultural identity. Here, you could also spot Li Ziqi, the influencer who had great success in popularizing Chinese traditional culture abroad.

2. The other spectacular dance afterward featured the Xinjiang Arts Theater Song and Dance Troupe, transporting viewers onto the ancient Silk Road through Dunhuang-inspired visual design. More about that later.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 21:28

“You’ll Like This for Sure”

After a song about the “Autumn Harvest” (来晒秋) featuring the massively popular Phoenix Legend pop duo together with the Ningxia Zhongning County Farmer Choir, we’re now arriving at the “comedy short drama.”

This is called “You’ll like this for sure” (喜剧短剧).

Interestingly, you see that the Spring Gala is choosing to cast faces from different talent pools, and many more are coming from China’s short drama industry. This is a gradual shift, where the directors are really aiming at younger audiences, mixing the older faces with young talent.

This whole sketch is about the addictive attraction of algorithm-driven content feeds on Chinese platforms like Douyin or Kuaishou. And although a lot of it is meant to be funny, there’s always a more serious undertone. In this case, reflecting on a generation of netizens who can’t even have dinner without watching short videos. This sketch seems to be quite well-received.

🕒 Feb 16, 21:32

Human Resonance — Li Jian

This song was released a few days before the Gala.

This song also marks Li Jian’s first return to Chunwan for the first time in 13 years, something many fans seemed happy about.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 21:40

The Yiwu Stage

The Yiwu stage – pay attention! This segment fetures Lionel Richie next to Jackie Chan, which is a very deliberate meeting of the stars, a meeting of East-West kind of narrative.

Why Yiwu? Yiwu is practically a factory of the world, and aso called China’s most cosmopolitan small city, since it’s a place where people from all over the world come together – you can hear Arabic, Spanish, and Uyghur on the same street.

Well here’s Lionel! Singing “We are the World” with Jackie Chan. I somehow envisioned him to be THERE in Yiwu, but it’s a studio recording and does not appear to be live, which, I’ll admit is a bit of a disappointment.

🕒 Feb 16, 21:46

Galloping Sea-Bay Horse

This is a song by Wurina and Aruna together with grassland performance group Wulanmuqi.

Here we see the beautiful AI-generated horses in the background, which I had been reading about before the Gala.

Apparently, the horses sometimes galloped too quickly or too slowly, so it was a challenge to integrate the AI visuals with what was happening on stage.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 22:03

Too much tech?

After a VERY high-energy song about “Fortune at your fingertips” (手到福来), featuring Hong Kong film legend Tony Leung Ka-fai (梁家辉) and mainland actress Liu Tao (刘涛), we’ve arrived at the next comedy sketch.

Meanwhile, online, there are people complaining about the lack of funny jokes in the show (it’s a complaint every year) and the abundance of robots. Some even suggest that many of the songs sound like they were written by AI.

Noteworthy is not just how much AI & robots appear in this show, but the sponsors of the Gala are also overwhelmingly from the tech environment. Out of nine announced sponsors, only two were traditional liquor brands.

The companies behind the robots reportedly invested around 100 million yuan (14 million usd) to get their robots on stage. This is the first time we’re not just seeing dancing robots, they’re also in the martial arts sketches, and even in the comedy skits. For many, it’s just too much. Another problem: they lack comical skills.

Another unexpected effect of this robotization of the Gala is that while many viewers are usually watching to see if any of the singers or actors make mistakes, they’re now waiting for a robot to do something wrong.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 22:14

Tears for Mum

The “jellyfish dance” with the beautiful colors is called “Joyful Rain” (喜雨) featuring lead dancer Meng Qingyang (孟庆旸) together with the Zhejiang Conservatory of Music – these are the kinds of dances Miranda and I always love the most,

The song with the tearful audiences is called “Mom Has a Cinema” (妈妈有座电), and was made with guidance of the famous Zhang Yimou.The singer was Deng Chao (邓超), and I’m not sure if the lady on stage was their actual mother. Correction: it’s the actress Chi Peng (迟蓬).

The song showed the milestones of a child’s growth and the unbreakable connection between mother and child.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 22:22

Faye Wong and Taiwan Nostalgia

Here we have arrived at Faye Wong’s performance, which was one of the songs that people looked forward to the most, mainly just because she is such a beloved singer. It’s titled “The Moment We Experienced Together” (你我经历的一刻)

Before Faye Wong: the song “Treasure Island Love Song”, the song invoking the most Taiwan Nostalgia of the night, although there was less political visual messaging than I expected.

This performance also included the Taipei-born Ouyang Nana, alongside a stacked cast of Taiwan-born artists.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 22:31

Meanwhile on Douyin & Bilibili

The platform Bilibili just posted about the most frequently sent bullet comment (danmu) during their Spring Festival Gala livestream. It is not “great”, “wonderful”, or “spectacular,” but: “Ah?” / “Huh?” The peak moment was apparently during one of the sketches, leaving viewers a bit confused rather than humored, apparently.

Also, meanwhile, some netizens are noting that Douyin users are complaining that criticising the Gala is apparently not allowed on the platform. On On Weibo, criticism of the Gala seems to have already been restricted for several years.

This censorship and control of the narrative surrounding the Gala makes it extra noteworthy that Bilbili has opened up its on-screen commenting for the Gala – although it does take some time for the comments to show up on screen (they are filtered, as well).

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 22:50

From Harbin to “Let Me Be Young Again”

Harbin is one of the sub-venues this year, and in its Gala segment, the city was portrayed as a cold place with an unexpectedly warm heart. It has become very popular in recent years during the Spring Festival travel season for its snow attractions and famously friendly locals. (Unfortunately, it’s also been quite literally warm — just this weekend, an 18-meter-high snowman had to be demolished after temperatures rose above 0°C, creating the risk that the entire sculpture might collapse.)

The mother-and-child duet featured a song from the 2024 feminist film Her Story (好东西), which is noteworthy. The film faced considerable backlash from some men online, and the actors were subjected to waves of slander. Its inclusion in the Gala feels meaningful.

“Let Me Be Young Again” (许我再少年), performed by Wei Chen (魏晨) and Liu Yuning (刘宇宁), is a Gala-commissioned original song, meaning it was written specifically for the 2026 Spring Festival Gala and kept fully unreleased before the broadcast. Its placement is deliberate. Appearing in the later segment of the program, close to 11 PM, the song is an hour before midnight in the “emo-core” of the Gala, a moment typically reserved for more reflective and sentimental songs.

Following this song is the Gala’s annual xiqu (戏曲, traditional Chinese opera) showcase segment. According to reports released before the show, the segment brings together excerpts from multiple major regional opera forms, specifically Jingju/Beijing opera (京剧), Pingju (评剧), Yueju/Shaoxing opera (越剧), Yueju/Cantonese opera (粤剧), and Yuju/Henan opera (豫剧), fused into 1 single creative medley.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 22:54

We just noticed..

Those who have followed the Gala for many years may recall that performers from Taiwan, Macau, or Hong Kong were typically always introduced with on-screen credits noting where they were from. It is unclear whether this is the first year that practice has been dropped, but it appears to have changed and they no longer do that. The shift may reflect a subtle move in emphasis from highlighting “two systems” toward a stronger focus on the idea of “one China.”

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 23:03

A little joke when watching the magic segment. This post said, “When you show your tongue piercing to your relatives.”

Another general sentiment was also that the magic tricks were more funny that the skits, which were meant to be comical.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 23:11

The night is suddenly going so fast! We’ve seen a so-called “micro-musical”, titled “Every Ray of Light” (每道光), which is meant as a tribute to all the workers. That’s why you saw delivery guys, factory workers – many of them actually also really doing these jobs and thus mixing the celebrities with the real-life workers.

The song afterwards (小家年年) mixed some elements of singing art from Suzhou with pop song format.

The short movie or “micro movie” was introduced a few years back as a recurring part of the Gala. This one, titled “My Most Unforgettable Tonight”, features China’s most famous comic duo Shen Teng (沈腾) and Ma Li (马丽). In the “behind-the-scenes” movie, they’re joined by robots from Galaxy Universal, one of the four major companies sponsoring the Gala this year.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 23:17

How serious is criticizing the Gala, really?

Since we’re seeing quite a lot of people criticizing the Gala, often in soft ways, it raises the question of how restricted criticism really is. As is often the case with China’s online dynamics, it’s not entirely black and white. Still, posting a strongly critical video on Douyin does not seem very feasible this year. Even a video by well-known Chinese comedy star Papi Jiang, posted before the Gala, was taken down. In a humorous tone, she had made some predictions about how the Gala might feel less creative or a bit cringe this year. Apparently, that was a step too far. (Link to video: https://youtu.be/zF9R5ry-gVY?si=ub7UFKA4ax21eRUV)

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 23:26

Poking fun at lazy local authorities

The sketch “Here Again” (又来了) is described as rather “brave” by some viewers. It pokes at local authorities doing fake “field visits” yet not solving any substantial issues for the people.

This strikes a chord with people who can recognize this as a real issue of different departments trying to avoid their own responsibilities, and trying to leave it to others. Some viewers appreciate a sketch like this pointing at real frustrations in society.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 23:34

Hefei is in the spotlight

This is the first time for Hefei to be featured as a sub-venue during the Chunwan. As for every city featured in the mega show, it’s an important moment for city marketing.

The venue featured is Luogang Park (骆岗公园), a repurposed former airport transformed into what is described as the world’s largest urban park.

Hefei, capital of Anhui, has a booming drone industry, which is also why you see so many drones in this segment.

At the same time, Anhui is one of China’s most invisible provinces online. Many people don’t know that the University of Science and Technology of China is in Hefei; they all think it’s in Beijing. So a bit more publicity for Hefei definitely can’t hurt.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 23:38

“Bottom of the Dream” (梦底)

We just saw “Bottom of the Dream” (梦底), featuring singer Hai Lai Amu (海来阿木) in his third consecutive Spring Festival Gala appearance. As a result, some commenters joked that he was “treating the Gala like his regular workplace” (把春晚当工位了).

Some people are joking about the dancer in the performance, because she seemed to overshadow the singer.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 23:48

Stamping the Rhythm

We just saw an unlikely combination of performers, which is pretty cool: the Minzu University of China together with the Hungarian National Folk Ensemble and the Jesús Carmona Spanish Dance Company,

Then it’s time for a more childlike and playful song: “Happy Little Horse” (快乐小马).

The next performance is titled “Painting the New Spring” (绘新春) and it’s quite spectacular, featured performers from Austria together with the Henan Provincial Acrobatic Troupe.

🕒 Updated: Feb 16, 23:56

The only military song of the night

Every Gala usually features one military song (军歌). This is “My Post, My Watch” (战位有我在), the only PLA-dedicated song at the Gala this year. The performers are from the PLA Cultural Arts Center, which was established in April 2018 through the merger of the former August First Film Studio, the PLA Song and Dance Troupe, Drama Troupe, Opera Troupe, and Military Band under the Central Military Commission Political Work Department.

This segment appears to mostly emphasize duty, vigilance, and each soldier’s personal commitment to their post, highlighting different roles across the military.

🕒 Updated: Feb 17, 0:00

Positive energy

So far, ethnic minorities, farmers, and traditional opera have all been featured as unmissable elements of every Gala night. The song “Searching for Dreams Across Mountains and Seas” (山海寻梦), is described by Chinese media as a tribute to all Chinese people who strive, persevere, and dedicate themselves welcoming a new spring where “hearts find joy and careers find success” (心有所悦、业有所成).

A classic Gala genre of inspirational zhengnengliang (“positive energy”) songs that usually appear just before the finale, which is where we are now!

🕒 Updated: Feb 17, 0:02

It’s midnight! Happy Year of the Horse!

🕒 Updated: Feb 17, 0:13

It’s not over yet

As it’s past midnight, we’ve reached the final stretch of the show, though there’s still a bit to go.

After a cheerful song about visiting family (“A Guide to Visiting Relatives,” 串门指南), we now see the beautiful performance “Riding the Wind” (驭风歌) featuring Jason Zhang.

Meanwhile, online criticism of this year’s Gala also seems to be growing. Is it really this year’s show, or is this simply the usual annual debate? Perhaps it’s both, as a common saying goes: “There’s never a worst, only worse than last year,” (中央春晚,没有最烂,只有更烂.) Much of the criticism right now is directed at the heavy use of robots. Among the different sub-venues, Yiwu is also drawing critique for highlighting the city’s commercial/capitalist side while choosing the song “We Are the World” which is meant to emphasize collective goodwill and charity and is one of the most famous charity songs ever made.

🕒 Updated: Feb 17, 0:18

Guaranteed Satisfaction

This is the final comedy sketch of the night, titled “Guaranteed Satisfaction” (包你满意). (There used to be many more of these, but with greater focus on song, dance, and tech, there is now less room for sketches, which are also often less popular among younger viewers.)

You might notice a format called “three-and-a-half sentences” (三句半), which sometimes appears in sketch comedy and crosstalk (including in the opening lines here). The first three lines are rhythmic or rhymed, while the fourth is only half a sentence — usually a short, punchy, rhyming tag. This is one of the most common opening formats in language-based performances on the Gala, a style that traces its origins to Beijing.

This particular sketch is described as a grassroots comedy centered on everyday consumer disputes, featuring Sha Yi, one of China’s veteran comic actors.

🕒 Updated: Feb 17, 0:22

The most meme-worthy moment of the night

It seems the Gala moment many people are joking about most is the Cai Ming sketch, in which she plays a little grandma employing robots in her home for all kinds of tasks. Funnily enough, many netizens, tired of being asked when they will finally settle down, have found an unlikely hero in Cai Ming, sharing:

“My parents: If you don’t have children in the future, who will take care of you when you’re old?”

“Me:”

🕒 Updated: Feb 17, 0:40

Brother Legend

Unlike Lionel, John Legend is present at the Gala itself. In Chinese, he is called 传奇哥: “Brother Legend.” This “Love Medley” also features Hélène Rollès (France) and Westlife (Ireland).

Westlife the band is still very popular in China. In 2024 they even allowed a Chinese AI platform to use their voices for singing.

🕒 Updated: Feb 17, 0:43

“Chasing Shadows” (追影)

Still want to briefly return to the act we saw before the street dance number “Sounds of Spring” (新春之声), which is “Chasing Shadows” (追影).

A truly beautiful piece, led by dancer Zhang Han (张翰) from Hubei. Zhang is best known for his role as the male lead Xi Meng in the dance-drama “Only This Green” (只此青绿), inspired by the Song dynasty painting A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains (千里江山图). The production was adapted into a film in 2024 starring Zhang.

The 2022 Gala actually also included a dance that was inspired by the painting which was stunning.

The other song that followed, Gongxi Facai (恭喜发财), can be seen as the Chinese New Year version of “All I Want for Christmas Is You”: every New Year season, it’s the song you hear everywhere, from the streets to the supermarkets, and it has become a meme in much the same way.

Meanwhile, there have also been some online comparisons between the robot shows in 2025 versus 2026, showing just how fast development is going. At this speed, wonder what the Gala will look like in 2027 and beyond!

🕒 Updated: Feb 17, 0:45

A different “Unforgettable Tonight”

Legendary singer Li Guyi (李谷一), who first performed “Unforgettable Tonight” (难忘今宵) in 1984 as the Gala’s signature closing song, has confirmed she will miss the show again due to health issues, marking her fourth consecutive absence since 2023.

Instead, we are seeing a different kind of “Unforgettable Tonight” (难忘今宵). The Gala appears to be shaping a new closing tradition without Li Guyi, this time featuring children and performers with disabilities, incorporating sign language and creating a more inclusive, human ending to an otherwise highly “robotic” show.

Performers include the Beijing Philharmonic Choir (北京爱乐合唱团), the Galaxy Youth TV Art Troupe (银河少年电视艺术团), and the China Disabled People’s Performing Art Troupe (中国残疾人艺术团).

Thank you for reading along, and I wish you a very happy and healthy Year of the Horse!

If you appreciate what we do and would like to receive the next newsletter on the latest Spring Festival trends, please don’t forget to subscribe. Signing off now, and thanks to Miranda and Ruixin for staying glued to the screen with me tonight. Until next time!

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Spring Festival Trend Watch: Gala Highlights, Small-City Travel, and the Mazu Ritual Controversy

Inside Chunwan 2026: China’s Spring Festival Gala

The Fake Patients of Xiangyang: Hospital Scandal Shakes Welfare System Trust

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West