China Digital

The Lanjisu Fire That Changed China’s ‘Wangba’ Era

The tragic Lanjisu fire led to a nationwide crackdown on internet cafes in China.

Published

7 years agoon

A Beijing internet cafe fire that killed 25 young people in 2002 has become part of China’s collective memory: it was a shift in China’s internet cafe era. June 16 marks the anniversary of this tragic event.

On June 16, 2002, at 2:40 a.m., a devastating fire broke out at a second-story Internet cafe (wangba 网吧) in Beijing’s Haidian, the city’s university district.

News of the tragic fire shocked the entire nation. The fire had instantly killed twenty people and severely injured 17, of whom five later died in the hospital.

All of the dead and injured people were students; 12 of them were from the prep school of the Beijing University of Science and Technology (Wang 2009, 86).

Lanjisu fire, June 16 2002.

Although it did not take long for firefighters to arrive that night, the fire at the Lanjisu (蓝极速, ‘Blue speed’) internet cafe was mainly so disastrous because windows were firmly secured with iron burglar-proof bars, leaving no option for people to escape. The only door was locked; it happened more often that wangba owners would (illegally) operate overnight behind locked doors (Qiu 2009, 33).

Investigators later ruled arson as cause of the fire at the cafe, which was located at Xueyuan Road 20. Traces of gasoline were discovered at the scene, and two teenage male suspects (13-year-old Zhang and 14-year-old Song) were arrested two days later.

The teenage boys were middle school students who used to play games at the internet cafe, but had gotten into a quarrel with other visitors and were not allowed to come in. To take ‘revenge’, they had purchased 1.8 liter of gasoline at a nearby gas station just 3-4 hours before they committed arson.

One of the suspects in 2002 (people.com.cn).

It was later revealed that the two boys both came from poor and shattered families, involving drugs and crime (Lifeweek 2003; Qiu 2015).

In August of 2002, a Beijing court sentenced the 14-year-old boy (Song X.) to life imprisonment, while the 13-year-old was sent to a juvenile re-education center as he was under the age of 14.

A third person, a 17-year-old female also named Zhang, was sentenced to 12 years in prison for being an accomplice; she gave the boys money to buy the petroleum, and knew what they were up to. A fourth minor, a 14-year-old boy by the name of Liu, was sentenced to 18 years in prison for being part of the arson plan. The internet cafe owner was sentenced to 3 years in prison for breaching business and safety rules. The gas station was fined 50,000 yuan for selling gasoline to two minors (Lifeweek 2003; Sina 2008).

A turning point in the wangba boom

The Haidian Lanjisu fire had a big impact on China’s booming internet cafe culture. Internet cafes had been mushrooming in China since the mid and late 1990s. It was the time of Tencent’s highly popular instant messaging software OICQ and multiplayer online games. By 2002 there were thousands of wangba across Chinese cities, many of them unlicensed and illegal, with no fire control equipment.

Internet cafe in 1990s (new.qq.com).

The Lanjisu fire made the problem of China’s wangba a national concern. Not just the unsafe conditions were a reason for worry, but also the impact the internet cafes had on China’s youth, with students spending days on end playing online games in these smoky rooms, leading to a rise in school absence and internet addiction. Beijing’s vice mayor Liu Zhihua condemned internet cafes as “opium dens” for the country’s youth.

The fire led to a huge crackdown on illegal internet cafes. The Beijing authorities launched a campaign that would stop the development of new internet cafes and that would screen all existing wangba one by one, and to close all unlicensed businesses immediately and to confiscate their operational tools (Wang 2009, 87). Across the country, approximately 400,000 internet cafes were closed (Sina 2008).

Second hand confiscated wangba computers (http://www.hkcd.com/).

It also led to the implementation of new rules, such as that there could no longer be internet cafes within a 200-meter radius of schools, that minors were not allowed to enter, and that they had to be closed between midnight and 8 am (Venkatesh 2006, 55)

Since 2005, the remnants of the Lansiju internet cafe have been on display at the Haidian Safety Museum.

Image via People.cn.

The fire is remembered in China as the “6.16 Wangba Big Fire” (6·16网吧大火), and is still being discussed on Chinese social media to this day.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

References

Qiu, Jack Linchuan. 2009. Working-Class Network Society

Communication Technology and the Information Have-Less in Urban China. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Qiu, Jack Linchuan. 2015 (2009). “Life and Death in the Chinese Informational City: The Challenges of Working-Class ICTs and the Information Have-less.” In: Living the Information Society in Asia, Erwin Alampay Alampay (ed), 130-157. ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute.

Sina. 2008. “北京蓝极速网吧老板今安在.” Sina News, 29 Dec http://news.sina.com.cn/s/2008-12-29/100416941011.shtml [16.6.18].

Venkatesh, P. 2006. “China on the I-way.” In: Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases, Hitt, Duane & Hoskisson (eds), chapter 2. Mason: Thomson Higher Education.

Wang, Xueqin. 2009. “Internet Cafes. What else can be done in addition to rectification?” In: Good governance in China–a way towards social harmony : case studies by China’s rising leaders, edited by Wang Mengkui, Lchapter 8. London & New York: Routledge.

Zhuang, Shan 庄山, Ke Li 柯立, Li Wei 李伟, Wu Ang 巫昂. 2003 (2002). “两个纵火少年和25条生命” [“Two Minor Arsonists and 25 Lives”]. LifeWeek 2002 (26), online April 8 2003 http://www.lifeweek.com.cn/2003/0408/1594.shtml [16.6.2018].

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

From China’s first soap opera Yearnings to the rise of AI-fueled nostalgia.

Published

4 months agoon

July 2, 2025

The year is 1990, and the streets of Beijing’s Fangshan District are eerily quiet. You can almost hear a pin drop in the petrochemical town, as tens of thousands of workers and their families huddle around their televisions, all tuned to the same channel for something groundbreaking: China’s very first soap opera, Yearnings (渴望 Kěwàng).

Yearnings tells the story of Liu Huifang (刘慧芳), a female factory worker from a traditional working-class family in Beijing, and her unlikely marriage to university graduate Wang Husheng (王沪生), who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Liu finds an abandoned baby girl, she adopts her and raises her as her own, against her husband’s wishes.

The couple is unaware that the foundling is actually the illegitimate child of Wang’s snobbish sister, Yaru. After Liu and Wang have a biological son, the marriage comes under further pressure, eventually leading to divorce. Liu is left as a single mother, raising two children on her own.

Still from Yearnings, via OurChinaStory.

Drawing inspiration from foreign dubbed television shows, Yearnings was produced as China’s first truly domestic, long-form indoor television drama. Spanning 50 episodes, the series traces a timeline from the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s through to the late 1980s—one of the most turbulent periods in modern Chinese history.

Before the series aired nationally on CCTV and achieved record viewership, the first station to air Yearnings in the Beijing region was the Yanshan Petrochemical TV Station (燕山石化电视台), China’s first major factory TV station (厂办电视台) located in Fangshan District.

Here, in this town of over 100,000, Yearnings garnered an astonishing and unprecedented 98% audience share. The series was truly groundbreaking and became a national sensation—not just because it was China’s first long-form television drama, or because it was a locally produced drama that challenged the long-standing monopoly of state broadcaster CCTV, but because Yearnings marked a major shift in television storytelling.

Until then, Chinese TV stories had always revolved around communist propaganda, or featured great heroes of the revolution. Yearnings, on the other hand, was devoid of political content and focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary people and their everyday struggles—love, desire, marital tension, single motherhood—topics that had never before been so openly portrayed on Chinese television.

The show’s creators had perfectly tapped into what was changing: the Communist Party was slowly withdrawing from private life, and people were beginning to see themselves less defined by their work unit and more by their home life—as consumers, as partners and parents, as citizens of a new China filled with aspirations for the future. Yearnings’ storyline was a reflection of that.

Chinese-Style “Nostalgia Core”

Yearnings marked a cultural turning point, coinciding with the rapid spread of TV sets in Chinese households. In 1992, economic reforms triggered a new era in which Chinese media became increasingly commercialized and thriving, before the arrival of the internet, social media, and AI tools once again changed everything.

Today, Yearnings still is a topic that often comes up in Chinese online media. On apps like Douyin, old scenes from Yearnings are reposted and receive thousands of shares.

📌 It’s emblematic of a broader trend in which more netizens are turning to “nostalgia-core.” In Chinese, this trend is known as “中式梦核” (Zhōngshì Mènghé), which literally means “Chinese-style dreamcore.”

Dreamcore is an internet aesthetic and visual style—popular in online communities like Tumblr and Reddit—that blends elements of nostalgia, surrealism, and subconscious imagery. Mixing retro images with fantasy, it evokes a sense of familiarity, yet often feels unsettling and deserted.

The Chinese-style dreamcore (中式梦核), which has become increasingly popular on platforms like Bilibili since 2023-2024, is different from its Western counterpart in how it incorporates distinctly Chinese elements and specifically evokes the childhood experiences of the millennial generation. Content tagged as “Chinese-style dreamcore” on Chinese social media is often also labeled with terms like “nostalgia” (怀旧), “childhood memories” (童年回忆), “when we were little” (小时候), and “Millennial Dream” (千禧梦).

According to the blogging account Yatong Local Life Observer (娅桐本地生活观察), the focus on the millennial childhood can be explained because the formative years of this generation coincided with a decade of rapid social change in China —leaving little in today’s modern cities that still evokes that era.

🌀 Of course, millennials in the West also frequently look back at their childhood and teenage years, particularly the 1980s and 1990s—a trend also embraced by Gen Z, who romanticize these years through media and fashion. In China, however, Gen Z is at the forefront of the “nostalgia-core” trend, reflecting on the 1990s and early 2000s as a distant, almost dreamlike past. This sense of distance is heightened by China’s staggering pace of transformation, modernization, and digitalization over the past decades, which has made even the recent past feel remote and irretrievable.

🌀 Another factor contributing to the trend is that China’s younger generations are caught in a rat race of academic and professional competition, often feeling overwhelmed by the fast pace of life and the weight of societal expectations. In this high-pressure environment—captured by the concept of “involution” (内卷)—young people develop various coping mechanisms, and digital escapism, including nostalgia-core, is one of them. It’s like a cyber-utopia (赛博乌托邦).

🌀 Due to the rise of AI tools available to the general public, Chinese-style nostalgia core has hit the mainstream because it’s now possible for all social media users to create their own nostalgic videos and images—bringing back the 1990s and early 2000s through AI-generated tools, either by making real videos appear more nostalgic or by creating entirely fictional videos or images that recreate scenes from those days.

So what are we seeing? There are images and videos of stickers kids used to love, visuals showing old classrooms, furniture, and children playing outside, accompanied by captions such as “we’re already so far apart from our childhood years” (example).

Images displayed in Chinese Dreamcore.

And notably, there are videos and images showing family and friends gathering around those old big TVs as a cultural, ritualized activity (see some examples here).

Stills from ‘nostalgia core’ videos.

These kinds of AI-generated videos depict a pre-mobile-era family life, where families and communities would gather around the TV—both inside and outside—from classrooms to family homes. The wind blows through the windows, neighbors crack sunflower seeds, and children play on the ground. Ironically, it’s AI that is bringing back the memories of a society that was not yet digitalized.

Nowadays, with dozens of short video apps, streaming platforms, and livestream culture fully mainstream in China—and AI algorithms personalizing feeds to the extreme—it sometimes feels like everyone’s on a different channel, quite literally.

In times like these, people long for an era when life seemed less complicated—when, instead of everyone staring at their own screens, families and neighbors gathered around one screen together.

There’s not just irony in the fact that it took AI for netizens to visualize their longing for a bygone era; there’s also a deeper irony in how Yearnings once represented a time when people were looking forward to the future—only to find that the future is now looking back, yearning for the days of Yearnings.

It seems we’re always looking back, reminiscing about the years behind us with a touch of nostalgia. We’re more digitalized than ever, yet somehow less connected. We yearn for a time when everyone was watching the same screen, at the same time, together, just like in 1990. Perhaps it’s time for another Yearnings.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Sources (other sources included in hyperlinks)

Koetse, Manya. 2016. “From Woman Warrior to Good Wife – Confucian Influences on the Portrayal of Women in China’s Television Drama.” In Stefania Travagnin (ed), Religion and Media in China. New York: Routledge.

Rofel, Lisa B. 1994. Yearnings: Televisual Love and Melodramatic Politics in Contemporary China. American Ethnologist 21(4):700-722.

Wang, Dan (汪丹). 2018. “《渴望》的艺术价值” [The Artistic Value of Yearnings].” Originally published in Beijing Daily (北京日报), October 12, 2018. Reprinted in Digest News (文摘报), October 20, 06 edition. Also see Sohu: 当年红遍大江南北的《渴望》.

Wang Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, a Chinese television soap opera with a message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Zhuge Kanwu. 2021. “重温1990《渴望》:苦得“刘慧芳”希望被导演写“死” [Revisiting 1990’s Yearnings: The Suffering Liu Huifang Hoped to Be Written Off by the Director]. Zhuge Dushu Wu (诸葛读书屋), January 22. https://wapbaike.baidu.com/tashuo/browse/content?id=b699ee532cf79f862bfa14ad.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

Consumers are profiting from the full-blown delivery war between JD.com and Meituan—but is it just the same game with a different name?

Published

6 months agoon

April 30, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

In April 2025, China’s food delivery sector witnessed a somewhat dramatic development, which attracted major attention online, when Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com publicly challenged food delivery leader Meituan.

On April 21, JD.com posted a noteworthy open letter titled “To All Fellow Food Delivery Rider Brothers” (各位外卖骑手兄弟们) on Weibo. In this letter, they accused Meituan (though not explicitly naming them) of monopolistic practices, after the company allegedly forced their delivery staff to stop accepting JD’s delivery orders. If riders chose to deliver for both companies anyway, they’d risk being blacklisted.

JD therefore accused Meituan of unethical behavior, neglecting their workers’ welfare, and pressuring part-time couriers to choose between platforms.

In their letter, JD vowed to support the freedom of Chinese delivery riders to accept orders from various platforms, and pledged to support those who were being blacklisted by offering them sufficient order volumes and full-time positions with benefits, including employment opportunities for their partners.

The bold move, dubbed the “421 Food Delivery Incident” by netizens, ignited widespread online debate.

“Underdog” JD vs. Meituan: The Start of a New Delivery War

JD.com is a household name in China’s e-commerce industry, best known for its electronics retail business. In recent years, it has expanded into fresh groceries, online supermarkets, and instant delivery services. Meanwhile, China’s food delivery market has long been dominated by Meituan (美团) and Ele.me (饿了么), the latter owned by Alibaba. Before a recent online controversy brought attention to it, many people weren’t even aware that JD had entered the food delivery space.

JD’s entry into China’s thriving food delivery market hasn’t been too long ago—the company officially only announced its JD Waimai (京东外卖) food delivery service back in February this year.

Before JD, other major tech companies like Tencent, Baidu, and ByteDance had all tried (and failed) to challenge the dominance of Meituan and Ele.me. But JD has a strong advantage: a massive logistics system with over 300,000 (!) delivery staff. Its Dada (达达) on-demand delivery and local logistics platform also has nearly 1.3 million active couriers, making JD a serious new competitor in China’s food delivery market. Not surprisingly, JD has already started hiring away talent from Meituan.

Amid JD’s growing presence, a post surfaced in April, reportedly from Meituan executive Wang Puzhong (王莆中), mocking JD’s food delivery ambitions as laughable. He used harsh language, calling JD a “cornered dog” making a desperate move (狗急跳墙). Then, on April 15, Meituan’s Flash Delivery service (美团闪送) released a video teasing JD’s supposedly slow delivery speeds (#美团闪购疑似嘲讽京东#). The video showed a dog with the caption: “Your Dongdong is still on the way” — a direct jab at JD, whose mascot is a dog and whose founder, Richard Liu (Liu Qiangdong), is nicknamed “Dongdong.”

JD swiftly hit back. On April 16, a video from an internal JD meeting was leaked, widely seen as a deliberate PR move. In the video, JD founder Richard Liu criticized the food delivery industry, claiming platforms were making excessive profits while restaurants struggled to survive. “Running a restaurant is already hard, yet platforms—just middlemen—are making a fortune,” he said. Liu added that JD would cap its profit margin at 5% and offer full social insurance to its full-time couriers—setting the tone for the official statement that followed.

Then came JD’s April 21 post, which launched a series of serious accusations against Meituan. JD claimed that Meituan had long restricted part-time couriers from working with other platforms and had failed to provide any social insurance to its full-time riders for over ten years. It also criticized Meituan’s working conditions, accusing the company of exploiting riders through algorithm-driven pressure while ignoring their safety. Additionally, JD accused Meituan of squeezing restaurants for profit, turning a blind eye to unhygienic “ghost kitchens,” and neglecting basic food safety standards. The tone of the post was sharply critical.

The attack prompted Meituan to respond publicly. That same evening, it issued a statement on its official WeChat account, denying that it had ever restricted riders from working with other platforms. Meituan also pushed back by accusing JD of mistreating its own couriers, pointing to heavy fines and unfair internal policies as the real issue.

However, Meituan’s response did little to improve its public image. On Weibo and short-video platforms, public sentiment largely turned against Meituan. That night, a netizen posted that JD CEO Richard Liu himself had delivered their JD order. Stories of Liu chatting with riders and restaurant owners quickly went viral, reinforcing his image as a down-to-earth, working-class hero—and earning JD another wave of goodwill.

At the moment, JD enjoys strong public support—not necessarily because it’s doing everything perfectly, but because it has timed its entry well, casting itself as the underdog taking on Meituan, the widely criticized corporate giant.

The Meituan Backlash

There’s no doubt that Meituan is a true giant. In 2024, the company generated a staggering RMB 300 billion (about $41 billion) in revenue. But this delivery empire has long faced ethical criticism—and JD’s recent accusations on Weibo highlight issues that many in the industry have raised before.

Meituan’s commission rates for restaurants are notoriously high, typically ranging from 15% to 25%. According to reports, around 60% of restaurants on the platform operate at a loss—even as Meituan continues to post multi-billion-yuan profits year after year. Many restaurant owners have voiced their frustration online, saying Meituan initially attracted them with generous onboarding incentives, only to gradually increase commissions, service fees, and so-called “tech support charges.” In the end, even strong sales often fail to translate into real profit. Yet with fierce competition and Meituan’s dominance in the food delivery market, many restaurants feel they have no choice but to stay.

For workers, complaints from Meituan couriers are nothing new. The faster they deliver, the more the algorithm shortens their future delivery windows, while slower deliveries result in fewer order assignments. This creates a vicious cycle, pressuring riders to break traffic rules just to meet deadlines. Unsurprisingly, their accident rate is reported to be three times higher than that of express couriers. To make matters worse, Meituan has historically provided no social insurance—neither for full-time nor part-time riders—leaving them on their own when accidents happen. As some couriers bitterly joke, “We’re not people—we’re just human batteries.”

For consumers, the concerns are just as serious. As I noted in an earlier article, Meituan’s platform increasingly hosts “ghost kitchens”—delivery-only outlets that often operate in unsanitary conditions, producing low-cost, low-quality meals to support Meituan’s Pinhaofan service and fuel ongoing price wars. It’s hard to believe Meituan isn’t aware of these practices; it simply appears to look the other way.

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to Meituan’s ethical challenges. But for many users, they’re reason enough to delete the app—especially now that JD has positioned itself as a credible alternative.

Of course, few believe Richard Liu is driven purely by social responsibility—he’s long been skilled at presenting himself as a “man of the people.” In JD’s early days, he famously delivered electronics himself in a three-wheeler. Still, as many netizens have put it: “Judge by actions, not intentions” (君子论迹不论心). Whatever JD’s true motives, its current words and actions seem to align with the interests of ordinary consumers and workers. But the question remains: is that enough?

Different name, same game?

For many consumers, the showdown between JD and Meituan has been surprisingly entertaining, and even financially rewarding. The more intense the rivalry, the bigger the discounts. Netizens have been sharing screenshots of good deals they’ve scored from both platforms in recent days. Some media outlets have even declared, “Richard Liu is saving food delivery and changing the industry for good!”

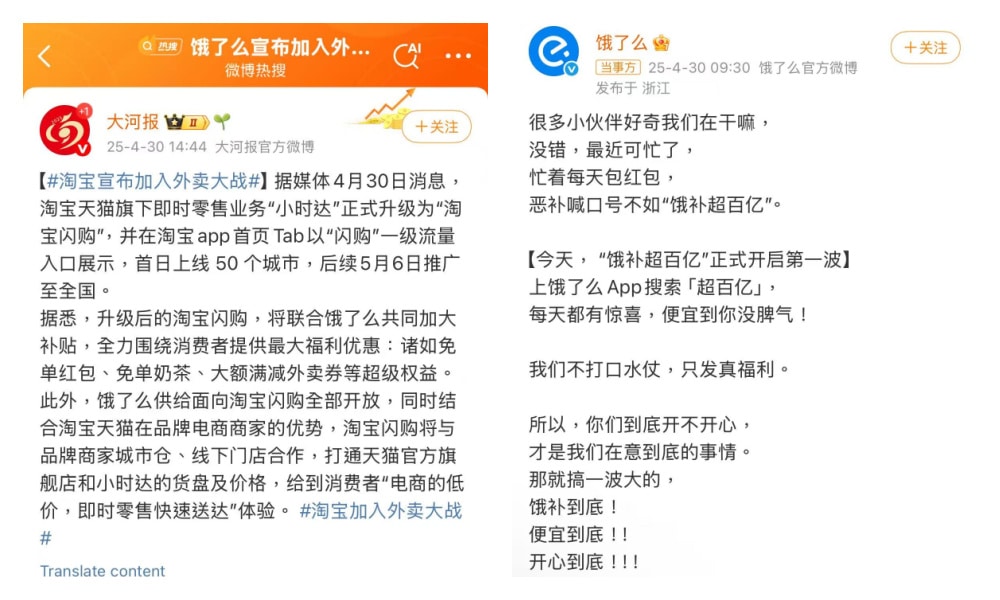

Meanwhile, Taobao and Ele.me have also announced that they’ll be joining the big JD–Meituan showdown by making themselves more competitive. “Taobao Flash Delivery” (淘宝闪购) will now be prominently featured on the main Taobao app, and Taobao and Ele.me will be more closely integrated under Alibaba to offer customers faster delivery times and the best prices. That means more offers—and good news for consumers.

Taobao and Ele.me also join the big battle

But offline, couriers are responding more cautiously. Rider welfare has quickly become a key issue in this corporate battle—and may even become a way for platforms to stand out in a crowded market. But big promises aren’t enough. Only real, visible improvements will earn riders’ trust.

Courier A Ping (阿平) has long been sharing food delivery vlogs online. He used to work for both Meituan and Ele.me. Since April 16, he’s started posting about JD’s delivery platform, and has raised many concerns: part-time riders apparently find it hard to get orders, the system is difficult to navigate, the dispatch logic is flawed, and the navigation is poor.

In the comments section, other couriers are joining the discussion, with many agreeing that JD’s current system only works for full-time employees. “If full-timers get the full benefits, insurance and everything, then it;s probably not that easy to become one,” one wrote. “JD looks promising now, with high pay and benefits, but give it time—it’ll end up the same as the others.”

Another rider, Yu (小于) isn’t too excited about the JD-Meituan feud either. “JD’s fine system is super strict,” he said. “At the end of the day, all these platforms are the same.” Whether JD is just using this moment for PR or genuinely stepping up to take on more social responsibility—only time will tell.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

“It’s in the Details” – The Xi-Trump ‘G2’ Meeting on Chinese Social Media

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

House of Wahaha: Zong Fuli Resigns

The Rising Online Movement for Smoke-Free Public Spaces in China

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

China Trend Watch: Pagoda Fruit Backlash, Tiananmen Parade Drill & Alipay Outage (Aug 11–12)

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral4 months ago

China Memes & Viral4 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral10 months ago

China Memes & Viral10 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained