Newsletter

Weibo Watch: Of Floods and Fragility

From devastating floods to an unexpected hit song, here’s a closer look at the top stories on Chinese social media.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #10

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Of floods and fragility

◼︎ 2. What’s Trending – A closer look at the top stories

◼︎ 3. What to Know – Highlighting 8 hot topics

◼︎ 4. What Lies Behind – Extreme weather and eco-anxiety in China

◼︎ 5. What’s Noteworthy – Hangzhou bear goes viral for looking too human

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Chaotic, expensive, anticipated: TFBoys concert

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Looking back: the Henan floods

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – “Love brain”

Dear Reader,

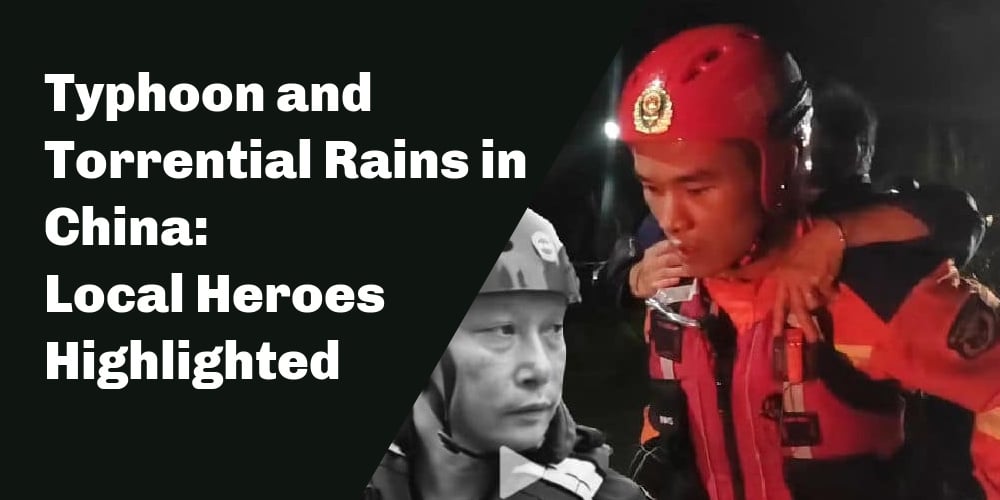

A young boy is rescued from electrocution in floodwaters by a bystander, a shepherd desperately guides his flock to safety as water levels surge, a small business owner scoops up his daughter as floodwater bursts into his shop – these are just a few instances of the surreal scenes that unfolded across various regions of China affected by the recent typhoon, heavy rainfall, and floods over the past week.

Chinese social media are inundated with hundreds of these videos capturing moments before and after the extreme weather and its impact on people and their surroundings throughout China. “In the eye of the storm, we are so fragile,” one person commented on a video depicting numerous wrecked cars stranded in a river.

The concept of life’s fragility has become a recurring theme in public discussions concerning the extreme weather in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, compounded by a 5.5 magnitude earthquake in Shandong. In light of these natural disasters, both official media and public online discourse in China sees some clear patterns in people’s responses and the types of narratives that gain traction.

Initially, social media platforms, particularly Weibo and WeChat, serve as avenues for individuals to seek and provide assistance. Swiftly, people establish groups, hashtags, and online communities to extend support to those requiring evacuation or other forms of rescue. Subsequently, a wealth of information circulates about self-protection measures, obtaining timely updates, and practical advice for critical situations. In the aftermath, narratives emerge about local heroes and rescue teams who willingly jeopardize their own safety to save the lives of others.

Emphasizing tales of unity and commending those “swimming against the tide” (逆行者) has become a recurring motif in Chinese state media’s response to disasters, whether it’s the Henan floods or the Chongqing fires. This pattern is an integral facet of the propaganda apparatus, and a recent article by The Economist—perhaps justifiably—criticized official media outlets for “dwelling on the heroics of soldiers, officials, and rescue teams.”

Nevertheless, these stories of local heroes also resonate with ordinary social media users. Consider the young man who uses his front-end loader to navigate treacherous river currents and rescue a family of three (plus their dog) in Beijing (see video). He is among those “everyday heroes” who risk their well-being to aid others during torrential rainfall and floods.

Propaganda aside, it is comprehensible that during moments of such fragility — when we recognize that it only takes a storm to change a life, a family, a village – it is precisely these topics centered around seizing control amidst chaos and extending help when circumstances appear hopeless that resonate most with people. We already know that we are fragile; it’s the incredible stories of resilience against adversity that provide hope and help bring a more positive outlook to a terrible situation.

This week’s newsletter features insightful contributions from What’s on Weibo news editor Miranda Barnes and contributor Zilan Qian.

As most of you know, there was a brief lull on the site as I traveled around China. We’ve since resumed our regular work routine. In the upcoming weeks, I hope to share more about my travels in What’s on Weibo articles by connecting online trends with offline realities. One of the destinations I visited was Zibo, a city that gained significant online attention earlier this year for its lively ambiance and BBQ dinners. I aimed to witness the aftermath of the social media frenzy, a topic I’ll delve into later (by the way, I greatly enjoyed the BBQ dinners and vibrant atmosphere!). If you’re planning a trip to China in the near future and have a question, or if you have seen a hot topic you’d like to know more about, please don’t hesitate to reach out — I’m always happy to connect.

Best,

Manya (@manyapan)

What’s Trending

1: Heroes in the Storm | In the face of powerlessness in the storm, it is the stories of people bravely taking control that offer a ray of light during darker times. The devastating rain that caused havoc in Fujian, Beijing, Hebei, Tianjin, and beyond this week has been trending all over Chinese social media. Amid all the reports, it is the stories of those emergency workers and local residents risking their own safety to rescue others are highlighted by media outlets and are collectively shared by social media users.

2: Ethnic-Themed Photo Trend | Patriotic, problematic, or purely photogenic? The trend of ethnic photoshoots has recently sprouted across Chinese social media platforms. What looks like a professional photoshoot in a fashion magazine, is actually a local photo service found in one of China’s many popular tourist destinations. Dressing up as various ethnic minorities is not just a souvenir for domestic Chinese travelers; it presents a chance to indulge in a glamorous fantasy. Read all about the ‘ethnic photoshoot’ trend in our feature article here:

3: A Sea of Books | Zhuozhou in Baoding, Hebei, is an important chain in China’s publishing industry, closely linked to the heart of the industry in Beijing. As devastating rainfall and flooding in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei left a trail of destruction across various sectors, Zhuozhou bore a heavy brunt of the impact. Some publishers saw their 8000 square book depots completely submerged, destroying 3.6 million books in a single warehouse alone. With millions of books and publications underwater, some booksellers will need to start from scratch, and some valuable out-of-print books will be lost forever. Most importantly: the staff members were all safely evacuated.

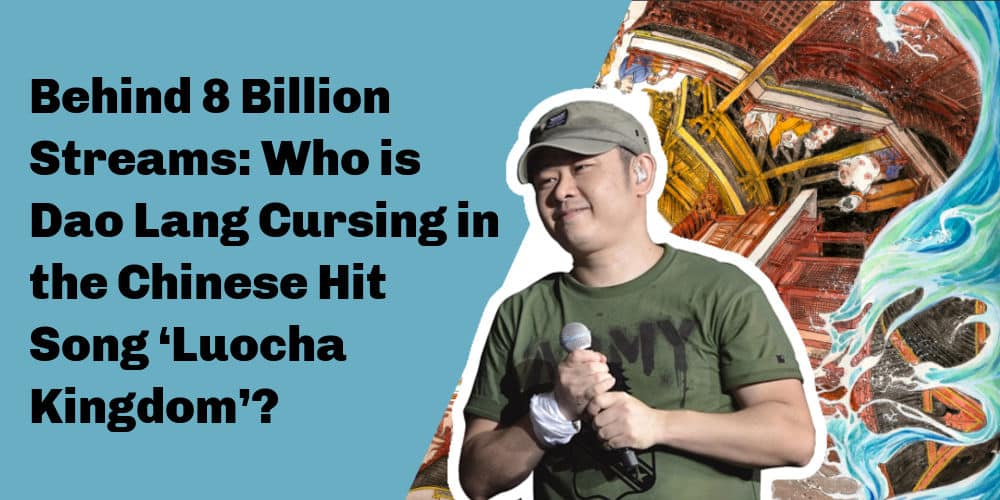

4: Eight Billion Streams | “Who is being mocked and cursed in this song?” This question has ignited a wildfire of speculation across the Chinese internet, as a recently released folk song by singer Dao Lang (刀郎) unexpectedly amassed a staggering 8 billion streams. The sudden surge in popularity of a song created by a low-profile singer, who has not participated in any major shows or held performances for the last few decades, has raised numerous questions: Who is the singer? What is in the song? And why has it become viral in China? We’ll answer some of these questions for you here.

What to Know

A “Barbenheimer” meme shared on Weibo by @娱乐时尚教父.

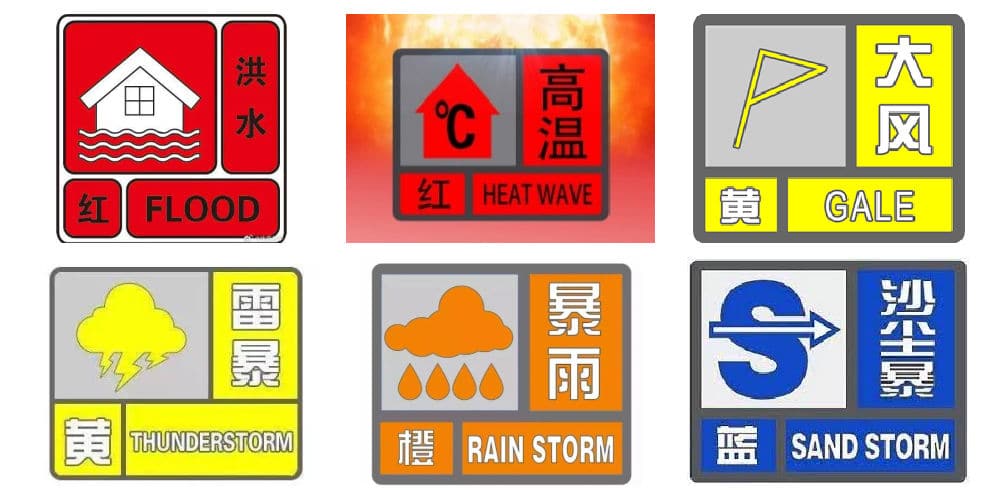

◼︎ 1. Typhoon and Floods in China. China was among the nations most severely impacted by Typhoon Doksuri and heavy rainfall this week, with Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei province region experiencing the most extreme weather. In Beijing alone, the past week’s rainfall shattered a 140-year-old record. The resulting floods continue to disrupt daily life in some Chinese regions, and this weekend witnessed large-scale evacuations in Shulan and Harbin. According to the latest reports, 22 individuals have lost their lives in Beijing, while Baoding saw a death toll of at least 10, and Shulan experienced six casualties (Many related trending hashtags on Weibo, one of them being ‘Doksuri’s Route’ #杜苏芮路径#, 2.3 billion views).

◼︎ 2. Earthquake in Shandong. This weekend, Weibo was overflowing with videos showing security footage of people responding to a 5.5 magnitude earthquake that hit Pingyuan county in eastern China’s Shandong province early on early Sunday morning at 2:33 am, injuring 21 people. The earthquake could even be felt in Beijing, about 220 miles away. The earthquake destroyed at least 126 houses. (Weibo hashtag “Shandong Earthquake” #山东地震#, 1.7 billion clicks in one day)

◼︎ 3. Anti Spionage Efforts. This week, China took further steps to enhance its counter-espionage efforts, with the Ministry of State Security releasing an online article titled “Mobilizing the Entire Society for Countering Espionage” (“反间防谍需要全社会动员”). This publication follows closely after the recent enactment of China’s new “Counter-Espionage Law” on July 1st. The article emphasizes that China’s ability to ensure robust national security against espionage relies on the comprehensive implementation of effective counter-espionage security measures across all levels of Chinese organizations, coupled with proper education of personnel within these organizations on how to prevent and thwart espionage activities. (Hashtag “Countering Espionage Requires Mobilization of the Whole Society” #反间防谍需要全社会动员#, 4.4 million views).

◼︎ 4. China Introduces Export Controls on Drones. Earlier this week, Chinese authorities unveiled new export controls affecting a wide range of drone types and associated equipment. Exporting these items will now require explicit export licenses, a measure allegedly introduced to uphold national security and interests. Consumer-grade drones meeting certain criteria will also be subject to these regulations. The controls will take effect on September 1 and are projected to remain in force for at least two years. According to foreign news media, the move could impact the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, where drones have become increasingly significant. (Hashtag: “Temporary Export Control Imposed on Certain Drones.” #对部分无人机实施临时出口管制#, 14+ million views)

◼︎ 5. Chengdu’s FISU World University Games. This week was the start of the 31st FISU World University Games in Chengdu, with President Xi Jinping presiding over the opening ceremony. Some social media highlights include China’s win over Japan for the women’s volleyball gold medal, as well as for the basketball, and Qin Haiyang breaking records and grabbing another gold medal with the 50-metre breaststroke. Eileen Gu also garnered online attention for being at the Games. The Games were originally scheduled to take place in 2021 but were postponed due to the pandemic. (Various related hashtags, including “Universiade” #大运会#, 150 million views in a single day.)

◼︎ 6. “Barbenheimer.” The release of the American films “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” has triggered a global “Barbenheimer” trend, and these movies continue to stir discussions in China. “Barbie” dominates China’s trending topics due to its international box office success and the emergence of numerous memes, fueling a shopping frenzy as various stores (including Miniso) launch special Barbie-themed product lines. While “Oppenheimer” is yet to hit Chinese screens, online conversations center around Japanese reactions to the film, which revolves around physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s involvement in developing the atomic bomb. In Japan, the movie has faced criticism for not adequately addressing the Hiroshima/Nagasaki tragedy, and the “Barbenheimer” memes linking Barbie and Oppenheimer are viewed as insensitive to the victims of the atomic bombings. Despite the gravity of the subject, numerous netizens find humor in the “Barbenheimer” (芭比海默) trend and its backlash in Japan. Given Japan’s historical denials of its own war crimes, some just don’t feel sympathetic towards the country’s sensitivities. (Hashtag “Barbie Boycotted by Japanese” #芭比被日本大规模抵制#, 530 million clicks).

◼︎ 7. LK-99 Superconductor.Chinese social media has been buzzing with discussions about room-temperature superconductivity since Wuhan University students claimed success in replicating the LK-99 superconductor crystal, previously created by a South Korean team. They posted a video online showcasing the crystal’s partial magnetic resistance, which garnered millions of views. However, skepticism persists within the scientific community as other research groups from China and India also reported successful experiments. While mainstream physicists remain cautious, they appreciate the public’s increased enthusiasm for scientific topics and room-temperature superconductivity in particular. (Hashtag: “Room Temperature Superconductor” #室温超导#, 120 million views)

◼︎ 8. Qin Gang Discussions. The abrupt dismissal of Qin Gang from his position as China’s foreign minister and the events leading up to it have garnered significant international media attention in recent weeks. Previously, Qin Gang’s noticeable absence from public discourse hardly stirred discussions on Chinese social media due to prevailing censorship and control. However, in the past week, we’ve observed a surge in Weibo posts featuring images and videos of Qin Gang, who previously held the role of China’s Ambassador to the United States (2021-2023). People are sharing archived interviews with Qin and sharing videos of him waving, almost as a farewell gesture. A prominent blogger, boasting over a million followers, recently uploaded a photo purportedly showing Qin Gang’s portrait hanging on a wall inside the US Embassy, commenting: “This portrait should be taken down; it’s now part of history.” Other bloggers are highlighting that, according to the official website of the Central People’s Government, Qin Gang still holds the position of State Councilor. Amidst these discussions, many netizens are speculating about his health and personal matters. “I’m not sure about his private actions, but there was nothing wrong with his public speeches,” one commenter wrote. (Weibo hashtag “Qin Gang Dismissed as Foreign Minister” #秦刚外长职务被免去#, “content not displayed according to relevant laws, regulations, and policies.”)

What’s Behind the Headlines

Extreme Weather and Eco-Anxiety in China

In the Western world, discussions about extreme weather are often accompanied by contemplations on the urgent implications of climate change and global warming caused by human activities. This trend continued this week as China experiences extreme weather conditions, prompting concerns and reflections on the repercussions of shifting climate patterns.

Interestingly, the phenomenon of “eco-anxiety” doesn’t resonate in the same manner on Chinese social media as it does in Western discourse, despite notable events like recording historically high temperatures in July, the impact of Typhoon Doksuri, and devastating floods. The disparity in online discussions concerning extreme weather and climate change raises questions about the factors influencing these differences.

Government authorities and mainstream media play a significant role in shaping these discussions. In contrast to the West, Chinese media doesn’t necessarily connect global warming to the nation’s manufacturing practices. A recent article published by The Economist discussed official and public discussions being “inward-looking” and avoiding direct engagement with climate change debates. However, additional factors contribute to the distinct responses of Chinese netizens, particularly regarding personal consumption and how individual behavior is connected to climate change.

During our upbringing in China, we were instilled with values of reducing waste in daily life, whether it’s water, food, or energy. Individuals believed they could contribute personally to “environmental conservation” by actions like turning off the shower while washing hair or setting the air-conditioning at 26°C instead of 24°C. Many Chinese people were, and still are, also constrained by limited resources due to income disparities: we literally couldn’t afford to waste resources. This reality likely contributes to the considerable discrepancy in public discourse, especially among older generations, when compared to Western perspectives. Under the topic of “extreme weather” (“极端天气”) on Chinese social media, discussions center around loss prevention, self-rescue strategies, and considerations for insurance. The primary focus is on personal safety and individual responses, rather than the collective responsibility of humanity for causing climate change.

It is interesting to point out that a recent Douyin hashtag “Refusing to Equally Share the Guilt” (“拒绝罪恶平摊论”), which emerged as a response to a viral eco-commercial depicting polar bears losing their ice habitat due to global warming, gained traction. It resonated with netizens and the responses were quite telling. Numerous popular comments highlighted the disproportionate emissions from wealthy minorities. The most-liked comment read: “I can’t even afford my own place or keep my air-conditioning on, yet I’m blamed for global warming. Who’s making this polar bear homeless? Who’s making me struggle? If I don’t share in their wealth, why should I share in the blame?”

What’s Noteworthy

Hangzhou Bear Goes Viral for Looking Too Human | A 4-year-old Malaysian sun bear from Hangzhou Zoo named Angela has captured international attention this week, sparking debates about its true identity – a bear or a human in a bear suit. The skepticism arose when a video recorded on July 27 at the zoo went viral, portraying the bear engaging with visitors and even standing upright like a human, causing its fur to crease in a fabric-like manner at the back. This peculiar trend quickly caught the eye of global media giants, including CNN, BBC, The Guardian, The New York Times, Washington Post, and Al Jazeera. The ripple effect extended to Chinese social media, where the endearing Hangzhou bear’s journey to American evening news delighted netizens.

The Hangzhou Zoo has firmly refuted all claims suggesting that the bear in question might not be a genuine bear. The zoo management emphasized that the ongoing scorching weather, with temperatures reaching 40 degrees Celsius, is already a challenge for the actual bears, let alone for humans donning fur costumes. Furthermore, the ability to stand upright is not unique to humans, as demonstrated by bears like Angela. In their natural habitat, bears often stand on their hind legs to gain a better view of their surroundings and to detect scents. This bear-or-human incident harks back to 2013 when another Chinese zoo raised eyebrows by attempting to pass off a furry dog as a lion. The enclosure at Luohe Zoo, labeled as the “African Lion,” housed a Tibetan mastiff dog instead. Additionally, in 2017, an unconventional “zoo” in Yulin captured attention as visitors flocked to see “penguins,” which turned out to be inflatable ones.

For Hangzhou Zoo, the incident has not harmed their reputation. On the contrary, it has only brought in more visitors wanting to see the now-famous human-like bear.

What’s Popular

2 Million Yuan for a TFBoys Concert Ticket?! | The TFBoys have been trending a lot this week as thousands of fans were highly anticipating the boy group’s August 6 concert. It is a very special date for the pop group, as they debuted on August 6, 2013, with their first single album “Start of Love” at the young ages of 12 and 13 years old. Now, ten years later, members Karry Wang (王俊凯), Roy Wang (王源), and Jackson Yee (易烊千玺) have become Chinese super-celebrities. Besides TFBoys’ success, the three have also been able to build their own individual careers as award-winning musicians and actors.

Celebrating a decade of the super popular TFBoys, ticket prices for their two-hour Xi’an concert became a hot topic on social media, with some prime front-row spot prices allegedly rising to a staggering – and somewhat ridiculous – 2 million yuan apiece (US$279K). Back in July, over four million fans were scrambling to try to get one of the 33,055 tickets that went on sale online. According to Shanghai Daily, it’s not just the ticket-sellers who are making an enormous profit out of the ten-year-anniversary concert; hotels in the area completely sold out and raised their room prices after the ticket sales went live. For all those who did not succeed in getting an actual ticket, they could still attend the concert via livestream for a maximum of 99 yuan (US$13.80).

On Sunday night, photos and social media videos depicted a chaotic scene at the beginning of the concert. Impatient fans swarmed the venue in large crowds, overwhelming security guards’ efforts to manage the crowd flow. The situation escalated to the point where some individuals fainted amidst the commotion.

What’s Memorable

The Henan Floods of 2021 | The extreme weather, heavy rainfall, and floods that occurred across China this week have brought back memories of the devastating floods that happened in China in 2021. The social media trends during China’s heavy rainfall and floods in July of 2021 showed the multidimensionality of online communication in times of disaster. Facing the devastating downpours, Weibo became a site for participation, propaganda, and some controversial profiting. For this week’s pick from the archive, we’ve selected our 2021 article highlighting these dynamics, as similar trends and topics have come up on Chinese social media over the past week.

Weibo Word of the Week, by Zilan

“Love-struck Brain” | Our Weibo Word of the Week is 恋爱脑 (liàn’ài nǎo), “love brain” or “brain of love,” referring to a love-struck or romance-focused brain.

‘Love brain’ is a term used to describe someone who prioritizes love and dating above all else and devotes their entire life to their partner once they fall in love. The term has increasingly taken on a negative connotation due to the Chinese younger generation’s increasing reluctance to embrace marriage and parenthood. Adopting a “love-struck mind” mentality is sometimes perceived as being irrational and misleading, implying a lack of drive in both personal life and career endeavors.

The recently premiered Chinese TV drama “Fireworks of My Heart” (“你是我的人间烟火”) has played a significant role in popularizing the concept of the ‘love brain’ (恋爱脑). The show’s female protagonist, a highly educated emergency department doctor hailing from an exceedingly affluent family, is cherished and pampered by her family. Nonetheless, despite her privileged background and demanding profession, she becomes utterly smitten with the male lead—a humble firefighter. She interprets even the most trivial of his gestures towards her, such as preparing a bowl of plain porridge or asking about her day, as profound expressions of his affection.

On Chinese social media platforms, numerous viewers express their displeasure with a female lead whose thoughts are consumed by romantic ideals. At a time when young people are facing numerous challenges, a plot that prioritizes love above all, to the extent that it compels a highly intelligent female doctor to place love at the forefront of her priorities, fails to strike a chord with the audience. What may have initially intended to be endearing now falls flat; viewers are eager for more substantial female characters beyond those who merely become absorbed in butterflies with their ‘love brain.’

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

You may like

Dear Reader

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

A look back at the three major phases of China’s social media — and why What’s on Weibo is evolving into Eye on Digital China.

Published

2 weeks agoon

November 12, 2025

This edition of the Eye on Digital China newsletter by Manya Koetse was sent to premium subscribers. Subscribe now to receive future issues in your inbox.

“Do you still remember going to the internet cafe, paying 2 yuan ($0.30) per hour during the day or 7 yuan ($1) for an all-nighter? Staying up playing games and surfing around?”

It’s the kind of content you’ll often see today on platforms like Douyin or Bilibili — nostalgic videos showing smoky internet cafes (wangba 网吧) from the early 2000s, where people chatted on QQ or played World of Warcraft on old Windows PCs while eating instant noodles. These clips trigger waves of nostalgia, even among internet users too young to remember that era themselves.

Internetcafe in 2005, image via 021zhaopin.com

The current nostalgia wave you see on Chinese social media is indicative of how China’s digital world has evolved over the past 25 years, shifting from one era to the next.

As I welcome a new name for this newsletter and say goodbye to ‘Weibo Watch’— and, in the longer run, to the ‘What’s on Weibo’ title, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic myself. It seems like a good moment to look back at the three major stages of Chinese social media, and at the reason I started What’s on Weibo in the first place.

1. The Blogging Boom (2002–2009): The Early Rise of Chinese Social Media

When I first came to China and became particularly interested in its online environment, it was the final phase of the early era of Chinese social media — a period that followed soon after the country had laid the foundations for its internet revolution. By 1999, the first generation of Chinese internet giants — Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Sina — had already been founded.

China’s blogging era began with the 2002 launch of the platform BlogChina.com (博客中国), followed by a wave of new platforms and online communities, among them Baidu Tieba and Renren. By around 2005, there were roughly 111 million internet users and 16 million bloggers, and the social impact was undeniable. 2005 was even dubbed China’s “year of blogging.” 1

Chinese writer Han Han (韩寒, born 1982), a high-school-dropout-turned–rally car racer, became one of the most-read figures on the Chinese internet with his sharp and witty blogs. He was just one among many who rose to fame during the blog era, becoming the voice of China’s post-1980s youth.

The rebel of China’s blog era, Han Han, became of voice of his generation.

When I moved to Beijing in 2008, I had a friend who was always out of money and practically lived in an internet cafe in the city’s Wudaokou district, not far from where I studied. We would visit him there as if it were his living room — the wangba was a local hangout for many of us.

Not only online forums and blogging sites were flourishing at the time, but there was also instant messaging through QQ (腾讯QQ), online news reading, and gaming. Platforms like the YouTube equivalents Tudou (土豆) and Youku (优酷) were launched, and soon Chinese companies began developing more successful products inspired by American digital platforms, such as Fanfou (饭否), Zuosa (做啥), Jiwai (叽歪), and Taotao (滔滔), creating an online space that was increasingly, and uniquely, Chinese.

That trajectory only accelerated after 2009, when popular Western internet services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, became inaccessible from within mainland China.

⚡ The launch of Sina Weibo in 2009 came at a crossroads for China’s social media landscape: it was not only a time when many foreign platforms exited China, but also when internet cafes faced major crackdowns.

As a foreigner, I don’t think I ever visited internet bars in Beijing anymore by that point — internet use had largely shifted to home connections. Laptop ownership was rising, and we all had (pre-smartphone) mobile phones, which we used to text each other constantly, since texting was cheaper than calling.

Some of the mobile phones in China’s 2009 top 10 lists.

Weibo came at just the right time. It filled the vacuum left by the online crackdowns across China’s internet while still benefiting from the popularity of blogging. Weibo (微博), after all, literally means “micro-blog” — micro because the number of characters was limited, just like Twitter, making short-form posts the main way of communication.

Weibo quickly became hugely successful, for many more reasons than just timing. Its impact on society was so palpable that its trending discussions often seeped into everyday conversations I had with friends in China.

In English-language media, I kept reading about what was being censored on the Chinese internet, but that wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to know — I also wanted to know what was on Weibo, so I could keep up with my social circles.

That question planted the seed for What’s on Weibo: the simple curiosity of “What are people talking about?” What TV series are popular? What jokes and controversies are everyone discussing (but that I never fully grasped)? I wanted to get a sense of an online world that was, in many ways, intangible to outsiders — including myself. As I had moved back to Europe by then, it was also a way for me to stay connected to those everyday conversations unfolding online in China.

With scissors, glue, and some paper, I started sketching out what a future website might look like.

Papercrafting the idea for a website named ‘What’s on Weibo’ in 2012.

And in March 2013, after doing my best to piece it together, I launched What’s on Weibo and began writing — about all kinds of trends, like the milk powder crisis, about China’s many unmarried “leftover men” (shengnan 剩男), and about the word of the moment, “Green Tea Bitch” (lǜchá biǎo 绿茶婊) — a term used to stereotype ambitious women who act sweet and innocent while being seen as calculating or cunning.

2. From Weibo to the Taobao Moment: China’s Mobile Social Era: (2010–2019)

Around 2014–2015, people started saying Weibo was dead. In fact, it hadn’t died at all — some of its most vibrant years were still ahead. It had simply stumbled into the mobile era, along with China’s entire social media landscape.

As mobile internet became more widespread and everyone started using WeChat (launched in 2011), new mobile-first platforms began to emerge.2 In 2012–2013, for example, apps like Toutiao and Xiaohongshu (小红书, RED) were launched as mobile community platforms. With the rapid rise of China’s new tech giants — Bytedance, Meituan, and Didi — a new mobile era was blossoming, leaving the PC-based social media world far behind.

Spending another summer in Beijing in 2014, I called it the “Taobao Moment” — Taobao being China’s most successful online marketplace, a platform for buying and selling practically everything from clothes and furniture to insurance and even Bitcoins. At the time, I thought Taobao captured everything Beijing was at that moment: a world of opportunities, quick decisions, and endless ways to earn and spend money.

On weekends, some of my friends would head to the markets near the Beijing Zoo to buy the latest dresses, purses, jeans, or shoes. They’d buy stock on Saturday, do a photo shoot on Sunday, and sell the goods online by Monday. You could often spot young people on the streets of Beijing staging their own fashion shoots for Taobao — friends posing as models, Canon cameras in hand.

During that period, What’s on Weibo gradually found its audience, as more people became curious about what was happening on Chinese social media.

Around 2016, Weibo entered another prime era as the “celebrity economy” took off and a wave of “super influencers” (超级红人) emerged on the platform. Papi Jiang stood out among them — her humorous videos on everyday social issues made her one of China’s most recognizable online personalities, helping to drive Weibo’s renewed popularity.

Witty Papi Jiang was a breath of fresh air on Weibo in 2016.

People were hooked on social media. Between 2015 and 2018, China entered the age of algorithm- & interest-driven multimedia platforms. The popularity of Kuaishou’s livestreaming and Bytedance’s Douyin signaled the start of an entirely new era.

3. The New Social Era of AI-fication and Diversification (2020–Current)

China’s social media shifts over the past 25 years go hand in hand with broader technological, social, and geopolitical changes. Although this holds true elsewhere too, it’s especially the case in China, where central leadership is deeply involved in how social media should be managed and which direction the country’s digital development should take.

Since the late 2010s, China’s focus on AI has permeated every layer of society. AI-driven recommendation systems have fundamentally changed how Chinese users consume information. Far more than Weibo, platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu have become popular for using machine-learning algorithms to tailor feeds based on user behavior.

China’s social media boom has put pressure on traditional media outlets, which are now increasingly weaving themselves into social media infrastructure to broaden their impact. This has blurred the line between social media and state media, creating a complex online media ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s not just AI and media convergence that are reshaping China’s online landscape — social relationships now dominate both information flows and influence flows. 3 Not everyone is reading the same headlines anymore; people spend more time within their own interest-based niches. It’s no longer about microblogging but about micro-communities.

China now has 1.12 billion internet users. Among new users, young people (aged 10–19) and the elderly (60+) account for 49% and nearly 21%, respectively. The country’s digital environment has never been more lively, and social media has never been more booming.

As a bit of a dinosaur in China’s social media world, Weibo still stands tall — and its trending topics still matter. But the community that was once at the heart of the Chinese internet has dispersed across other apps, where people now engage in more diverse ways than ever.

In China, I notice this shift: where I once saw the rise of Weibo, the Taobao boom, or the Douyin craze, I now see online and offline media increasingly converging. Social media shapes real-life experiences and vice versa, and AI has become integrated into nearly every part of the media ecosystem — changing how content is made, distributed, consumed, and controlled.

In this changing landscape, the mission of What’s on Weibo — to explain China’s digital culture, media, and social trends, and to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online spaces — has stayed the same. But the name no longer fits that mission.

Over the past few years, my work has naturally evolved from Weibo-focused coverage to exploring China’s digital culture through a broader lens. The analysis and trend updates will continue, but under a new name that better reflects a time when Weibo is no longer at the center of China’s social media world: Eye on Digital China.

For you as a subscriber (subscribe here), this means you can expect more newsletter-based coverage: shorter China Trend Watch editions to keep you up to date with the latest trends, along with other thematic features and ‘Chapter’ deep dives that explore the depth behind fleeting moments.

For now, the main website will remain What’s on Weibo, but it will gradually transition into Eye on Digital China. I’ll keep the full archive alive — more than twelve years of coverage that helps trace the digital patterns we’re still seeing today. After all, the story of China’s past online moments often tells us more about the future than the trends of the day.

Thank you for following along on this new journey.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 Liu, Fengshu. 2011. Urban Youth in China: Modernity, the Internet and the Self. New York: Routledge, 50.

2 Mao Lin (Michael). 2020. “中国互联网25年变迁:两次跃迁,四次浪潮,一次赌未来” [25 Years of China’s Internet: Two Leaps, Four Waves, and a Gamble on the Future]. 人人都是产品经理 (Everyone Is a Product Manager), January 3. https://www.woshipm.com/it/3282708.html.

3 Yang, Shaoli (杨绍丽). 2025. “研判2025!中国社交媒体行业发展历程、重点企业分析及未来前景展望:随着移动互联网兴起,社交媒体开始向移动端转移 [Outlook for 2025! The Development History, Key Enterprises, and Future Prospects of China’s Social Media Industry: With the Rise of Mobile Internet, Social Media Has Shifted to Mobile Platforms].” Zhiyan Consulting (智研咨询), February 7. https://www.chyxx.com/industry/1211618.html.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in the comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient — we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo.

Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. Both feature the same new content — so you can subscribe or read wherever you prefer. If you’re already subscribed on one platform and would like to move your subscription over, just let me know and I’ll help you get set up.

© 2025 Manya Koetse. All rights reserved.

China Media

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Published

8 months agoon

March 30, 2025

“This man is doing God’s work. In just six hours, he eliminated all Western media propaganda about China,” Chinese influencer Li Sanjin (李三金) said in one of his videos this week. The man he referred to, allegedly doing ‘God’s work,’ is the American YouTuber and online streamer Darren Watkins, better known as IShowSpeed or Speed, who visited China this week and livestreamed from various locations.

With 37 million followers on his YouTube account, Watkins’ visit hasn’t exactly flown under the radar. His streams from China have already accumulated over 17.5 million views on YouTube alone, and he also became the talk of the week on Chinese social media.

In China, the 20-year-old IShowSpeed is known as Jiǎkànggē (甲亢哥), or “Hyper Bro,” since the immensely popular YouTube star is known for being highly energetic.

Although IShowSpeed is originally known for soccer and gaming-related content, he’s been streaming live from various countries over the past year, from Ecuador to Bolivia, from Australia to Indonesia, from Romania to Japan, and also from the Netherlands, where a mob of fans harassed the YouTuber to such an extent that the influencer fled and panicked, until the police intervened and asked him to shut down the livestream for safety reasons — which he did not comply with.

It was not the only time IShowSpeed’s visit got chaotic. He also got into trouble during livestreams from other countries. While streaming from Norway, he injured his ankle and was swarmed by a crowd while trying to get out. In Greece and Indonesia, he had to ask for police support as well. In Thailand, he crashed a tuk-tuk into a temple wall.

In China, IShowSpeed’s livestreams went far more smoothly, and netizens, state media, and other official channels raved about his visit and its favorable portrayal of the country and its culture.

🔹 Symbol of Cultural Exchange & Positive Diplomacy

“Jiǎkànggē” became one of the viral terms of the week, on Weibo, Kuaishou, Douyin, and Toutiao. During his China trip, the livestreamer hit several YouTube milestones — not only breaking the 37 million subscriber mark while on stream, but also surpassing the magic number of 10 million views in total.

Watkins, also known for being (sometimes aggressively) loud and chaotic, suddenly emerged as a symbol of cultural exchange and positive diplomacy. The past week saw hashtags such as:

#️⃣”IShowSpeed gives young foreigners a full-window view into China” (#甲亢哥给国外年轻人开了全景天窗#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed’s Shanghai livestream breaks Western filter on China” (#甲亢哥上海直播打破西方对中国滤镜#)

#️⃣”American influencer IShowSpeed amazed by stable wifi on China’s high-speed train” (#美国网红甲亢哥被高铁稳定网络震惊#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed praised deep tried tripe for being incredibly delicious” (#甲亢哥赞爆肚太好吃了#), or

#️⃣ “IShowSpeed bridges the cultural divide” (#甲亢哥弥合文化鸿沟#).

While in Chinese media, Watkins was lauded for shining a positive light on China, this message was also promoted on English-language social media, where he was praised by the Chinese embassy in the US (#驻美大使馆称赞甲亢哥中国行#), writing:

Post by Chinese Embassy in the US on X, March 26.

“This 20-year-old American internet star is bridging cultural gaps through digital means and creating new channels for foreign audiences to better understand China.”

So what exactly did IShowSpeed do while in China?

On March 24, Watkins livestreamed from Shanghai. He wandered around the city center, visited a KFC, danced with fellow streamers, stopped by a marriage market, ate noodles, played ping-pong, had hotpot, joined a dragon dance group and got acquainted with some traditional Chinese opera performance, and walked along the Bund.

On March 26, he streamed from Beijing, starting in Donghuamen before briefly entering the Forbidden City—dressed in a Dongbei-style floral suit. He later took a stroll around Nanluoguxiang and the scenic Houhai lake, rode a train, and finally visited the Great Wall, where he did backflips.

In his stream on March 28, Watkins traveled to Henan to visit the famous Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng, hoping to find a master to teach him kung fu. He trained with Shaolin monks—footage that quickly went viral.

Lastly, on March 29, he opened his own Weibo account and published his first post. On Douyin, he shared a video of his visit to Fuxi Mountain in Zhengzhou, featuring the popular “Stairway to Heaven” tourist spot.

On social media, many viewers were captivated by the content. One major talking point was the remarkably strong internet connection that allowed him to livestream for six-hour stretches without losing signal in Shanghai. (Though his Beijing stream started off patchier, the drop was minor.) For many, it symbolized the quality of China’s 5G services.

Foreign viewers also praised how safe, friendly, and clean the country appeared, and how his streams highlighted various aspects of Chinese culture—from everyday people to traditional arts and local cuisine.

🔹 Telling & Spreading China’s Stories Well

It is no wonder the success of the Jiǎkànggē livestreams is celebrated by Chinese official media in an age where China’s foreign communication aims to increase China’s international discourse power, shaping how the world views China and making that image more credible, more respectable, and more lovable.

That’s not just an observation — it’s an official strategy. Introduced by Xi Jinping in 2013, “Telling China’s Story Well” (“讲好中国故事”) is a political slogan that has become a key propaganda strategy for China and continues to be a priority in finding different ways of promoting Chinese culture — new ways of telling China’s story in the social media age – while countering Western dominant narratives about China.

In increasingly digitalized times, it is not just about telling China’s story well, but also spreading China’s message effectively — preferably through genuine and engaging stories (Cai 2013; Qiushi 2021).

Especially young, non-official ‘storytellers’ can make China’s image more relatable and dynamic. One major example, highlighted in a 2022 case study by Zeng Dan (曾丹), is Chinese influencer Li Ziqi (李子柒). You’ve probably heard of her, or seen snippets of her videos: she creates soothing, cinematic content depicting China’s countryside lifestyle, focused on cooking, crafts, and gardening. With 26 million followers on YouTube, Li Ziqi became a viral sensation who successfully communicated an authentic and appealing ‘China story’ to a broad global audience.

Li Ziqi in one of her YouTube videos.

Although the calm and composed Li Ziqi and the loud, chaotic IShowSpeed couldn’t be more different, they have some things in common: both have large international fanbases, including their millions of YouTube subscribers; they offer perspectives that differ from Chinese state media or official channels; and they have the capacity not just to tell China’s story well, but to spread it effectively through videos and livestreams.

🔹 Spontaneous Stream or Scripted Propaganda?

IShowSpeed’s China streams have triggered a wave of responses from fans and viewers, sparking discussions across international social media and even making newspaper headlines.

In English-language online media spheres, there appear to be a range of perspectives on Watkins’ China trip:

📌 One prominent view—also echoed by various foreign influencers on YouTube and other platforms—is that IShowSpeed’s visit counters “Western media lies” about China and has successfully shown the “real China” through his livestreams. The Shanghai-based media outlet Radii claimed that “IShowSpeed’s China Tour is doing more for Chinese Soft Power than most diplomats ever could.”

📌 Others challenge this narrative, questioning which dominant Western portrayals of China IShowSpeed has actually disproven. Some argue that the idea of China being a “bleak place with nothing to do where people live in misery” is itself a false narrative, and that presenting IShowSpeed’s livestreams as a counter to that is its own form of propaganda (see: Chopsticks and Trains).

📌 There are also those who see Watkins’ trip as a form of scripted propaganda. To what extent were his livestreams planned or orchestrated? That question has become one of the central points of debate surrounding the hype around his visit.

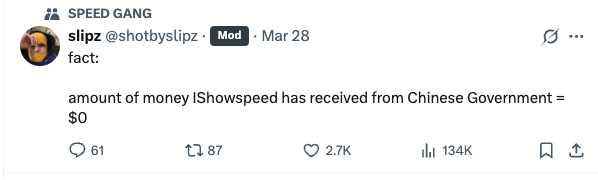

These rumors have been addressed by cameraman Slipz (@shotbyslipz), who took to X on March 28, 2025. Slipz posted that the team is “(..) not making political content, not any documentary and no journalism,” and later added: “Fact: amount of money IShowSpeed has received from Chinese Government = $0.”

But does the fact that IShowSpeed did not receive money from the Chinese government mean that it wasn’t also a form of China promotion?

➡️ Organized — it definitely was. Any media trip in China has to be. IShowSpeed would have needed a visa, he had translators with him, and throughout the streams it’s evident that local guards and public security officers were present, walking alongside and helping to keep things under control, especially in crowded areas and at major tourist spots — from Nanjing Road in Shanghai to an entire group of guards seemingly accompanying the entourage in the Forbidden City.

One logistical “advantage” to his visit was the fact that YouTube is blocked in China. While some Chinese fans do bypass the Great Firewall to access the platform, IShowSpeed remains far less known in China than in many other countries — a factor that likely contributed to how smoothly the streams went and helped prevent chaos. The team also launched a Douyin account during the trip, where he now has over two million followers. (To stream directly to their 37 million followers on YouTube, Watkins’ team either needed a VPN to access WiFi or had arranged roaming SIM cards to stay connected.)

➡️ Was it staged? Many parts clearly weren’t: casual public conversations, spontaneous barber visits in both Shanghai and Beijing (with barbers looking unsure of how to handle the situation), and wholesome fan encounters. There was even a moment when Watkins walked into a public restroom and forgot to mute the sound.

But other parts of the trip were undeniably staged — or at least framed to appear spontaneous. When visiting a marriage market in Shanghai, for instance, two actors appeared, including one woman with a sign stating she was looking for someone “capable of doing backflips.”

When Watkins took a “random” ride in what was described as the fastest car in China — the Xiaomi SU7 Ultra — the vehicle appeared to be conveniently parked and ready.

Similarly, when the streamer “ran into” Chinese-American TikTok influencer Miles Moretti (李美越) in Beijing, it turned out to be the person who would give him the now-iconic bright Dongbei flower suit and accompany him on his journey.

The ping-pong, the kung fu, the Peking opera, the hotpot, the Forbidden City tour — it all plays into the kinds of experiences that official channels also like to highlight. While likely planned by Watkins’ team in coordination with local partners, it was all far more orderly and tourism-focused than, for example, Watkins’ chaotic visit to the Netherlands.

Watkins and his entourage were also well-informed about the local dos and don’ts. At one point, Watkins even mentions “following the rules,” and when Moretti tells him mid-stream that “somebody very important lives on our left,” Watkins asks “Who?” — but the camera zooms out and the question goes unanswered, suggesting they may have been reminded that certain names or topics were off-limits (judge the moment for yourself here).

The livestream didn’t always go exactly the way Watkins wanted, either. When he attempted to take more random walks around the city, the crew appeared to be informed that some areas were off-limits, and he was asked to return to the car to continue the trip (clips here and here).

🔹 The “Nàge” Song

One major talking point surrounding IShowSpeed’s China livestreams was “the N-word.” No, not that N-word — but the Chinese filler word “nàge” or “nèige” (那个). Like “uhm” in English or “eto” in Japanese, “nàge” is a hesitation marker commonly used in everyday Mandarin conversation. It also functions as a demonstrative pronoun meaning “that.”

The word has previously stirred controversy because of its phonetic resemblance to a racial slur in English. In 2020, an American professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business was even temporarily suspended after using the word during an online communications class — some students misunderstood its context and took offense.

The word — and the song “Sunshine, Rainbow, White Pony” (阳光彩虹小白马) by Chinese singer Wowkie Zhang (大张伟), which repeatedly features the word nàge in its chorus — popped up multiple times during Watkins’ trip. The catchy tune essentially became the theme song of his visit.

The first nàge moment actually already appeared within the first five minutes of Watkins’ Shanghai stream, when a Chinese comedian approached him on the street, trying to recall a joke. “What?!” Watkins reacted, with laughter in the background. “That’s not a joke, you said n**! It’s my first five minutes in China!” he exclaimed, before patting the man’s back in a friendly gesture, clearly not offended.

🔄 It resurfaced again within the first hour when Watkins visited a marriage market and one of the performers sang the Wowkie Zhang song. Watkins initially acted shocked, then demanded they sing it again — only to burst out laughing and start singing along.

🔄 Later, he sang the song again with a street saxophonist and encouraged others to join in.

🔄 At other moments, he played up the drama again, feigning anger when a crowd broke into the chorus, and it became a recurring gag throughout the streams.

These incidents all seem staged. One of the main reasons Watkins is known to many netizens in China is because of an older video clip showing his exaggerated reaction to the nàge song — dating back to at least 2022. So while it may have looked spontaneous, Watkins was already familiar with the word and the viral song long before his China trip.The attention given to the nàge ‘controversy’ was likely amplified for views and engagement.

While Watkins was clearly in on this part of the show — as with others — he also seemed genuinely, and at times amusingly, unaware of many things in China. He repeatedly referred to RMB as “dollars,” mistook elderly women for retired YouTube streamers, and even assumed that a woman livestreaming near the Forbidden City was reading his chat and trying to collaborate with him — although she seemed totally uninterested and was just minding her own business.

🔹 A Win-Win Situation

In the end, IShowSpeed’s visit highlighted two sides effectively doing their job. Watkins and his team successfully arranged a YouTube trip that generated high ad revenue, attracted millions of new subscribers, and boosted his brand and global fame.

On the Chinese side, there was clearly coordination behind the scenes to ensure the trip went smoothly: avoiding controversy, ensuring safety, and showcasing positive aspects of Chinese culture. From traditional opera and kung fu to ping pong, IShowSpeed’s content gave center stage to the kinds of cultural highlights that align closely with China’s official narratives and tourism goals. Even if the government didn’t pay the YouTuber directly, as his team has emphasized (and there’s no reason to doubt them), the trip still fit seamlessly into China’s soft power strategy.

IShowSpeed’s China visit has created a unique media moment that resonates for several reasons: it’s the encounter of a young modern American with old traditional China; it is a streamer known for chaos visiting a nation known for control. And it brings different benefits to both sides: clicks and ad revenue for IShowSpeed, and free foreign-facing publicity for China.

No, IShowSpeed didn’t undo years of critical Western media coverage on China. But what his visit shows is that we’ve entered a phase where China is becoming more skilled at letting others help tell its story — in ways that resonate with a global, young, online audience. He didn’t do “God’s work.” He simply did what he always does: stream. And with China’s help, he streamed China very well.

There’s so much more I want to share with you this week — from Chinese reactions to the devastating Myanmar earthquake, to a recent podcast I joined with Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf (link in Dutch, for those interested). But it also happens to be my birthday today, and I’m really hoping to still grab some birthday hotpot — so I’ll wrap this up here. I’ll keep you informed on the other trends in the next newsletter.📨.

Best,

Manya

(@manyapan)

References:

Cai, Mingzhao 蔡名照. 2013. “Telling China’s Stories Well and Spreading China’s Voice: Thoroughly Studying and Implementing the Spirit of Comrade Xi Jinping’s Important Speech at the National Conference on Propaganda and Ideological Work [讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音——深入学习贯彻习近平同志在全国宣传思想工作会议上的重要讲话精神].” People’s Daily 人民日报, October 10. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1010/c1001-23144775.html. Accessed March 29.

Qiushi 求是网. 2021. “Xi Jinping: Telling China’s Story Well, Spread China’s Voice Well [习近平:讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音].” Qs Theory, June 6. http://www.qstheory.cn/zhuanqu/2021-06/02/c_1127522386.htm. Accessed March 29.

Zeng Dan 曾丹. 2022. “How to Tell China’s Story Well: Taking Li Ziqi as an Example [如何讲好中国故事——以李子柒为例].” Progress in Social Sciences 社会科学进展 4 (1): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.35534/pss.0401002.

What’s Featured

Quite terrifying and interesting, as this trending story touched upon so many different issues.

What started as a single snarky comment on Weibo spiraled into an online witch hunt, exposing not just some dark sides of online Kpop fandom but also, most importantly, the vulnerabilities in China’s digital privacy.

Read the story, the latest by Ruixin Zhang 👀

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral4 months ago

China Memes & Viral4 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained