China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Social Media in Times of China’s Flood Disaster: Participation, Profits, and Propaganda

Published

3 years agoon

The social media trends during China’s heavy rainfall and floods in July of 2021 show the multidimensionality of online communication in times of disaster. Facing the devastating downpours, Weibo became a site for participation, propaganda, and some controversial profiting.

This is the “WE…WEI…WHAT?” column by Manya Koetse, original publication in German by Goethe Institut China, visit Yi Magazin: WE…WEI…WHAT? Manya Koetse erklärt das chinesische Internet. Read this article in German here.

Starting on July 17, 2021, China’s Henan Province experienced extreme rain that led to record-breaking flooding and soon forced thousands of people to leave their homes, completely disrupting normal life.

Several places in the region saw unprecedented rainfall. From 8pm on July 19 to 8pm on July 20, the provincial capital Zhengzhou experienced 552.2 mm of rainfall, which is 3.5 times more rain than Germany saw during its heaviest rainfall in 75 years on July 14-15 of this year.

The death toll from the torrential rainfall has risen to at least 302 people, with many remaining missing.

As emergency situations occurred across the region, social media came to play an important role in the response to the natural disaster. Weibo, one of China’s biggest social media sites, was utilized as a communication tool during the floods by regular netizens, official channels, and companies.

While the extreme weather continued, the Henan flood disaster played out on social media in various ways. There were those helping, those profiting, and then there were those profiting from helping. We will highlight some of these dimensions within the social media responses to Henan’s catastrophic floods here.

People Helping People

There is one hashtag on Weibo that was breaking records in July: ‘Help Each Other During Henan Rainstorm’ (#河南暴雨互助#) received a staggering 16.9 billion clicks just a week after it was first launched.

By creating an online ‘Henan Help’ community, Weibo facilitated active public participation in providing immediate assistance to those affected by the extreme weather and flooding.

As described by Wendy Huang for What’s on Weibo (link), an enormous volume of messages starting pouring in on Chinese social media since the start of the heavy rainfall from people disseminating relevant information on available resources and from those seeking and providing assistance.

Rather than being a messy collection of individual posts, netizens collectively participated in verifying, summarizing, highlighting, and spreading the online help requests posted by people from different locations. In doing so, they helped in speeding up the rescue work.

This is not the first time for Weibo to play an important role during a crisis or emergency. When Sichuan Province was hit by a deadly earthquake in 2013, social media enabled a fast and free grass-roots response to the disaster. The Sina Weibo platform allowed for efficient, immediate crisis communication, leading to teams of volunteers – organized via Weibo – heading out to the disaster zone to deliver donated tents, blankets, water, etc. and provide other forms of assistance (Levin 2013).

During the early stages of the Wuhan COVID19 outbreak, social media platforms such as Weibo and WeChat were also used as practical communication tools for organizations and individuals to spread information or to ask for help. One example is how Weibo helped local volunteers organize teams to assist in taking care of people’s left-behind pets when they were unable to return to their homes due to quarantine or hospitalization.

As soon as the scale of the floods in Henan province became clear, social media users started donating money for flood relief efforts. By July 21st, while the videos of the devastating impact of the heavy rainfalls went viral, Weibo users had already contributed 20 million yuan ($3 million). That number soon rose significantly as more netizens, social influencers, and celebrities also started to donate and promote charity foundations.

Simply posting, replying, forwarding, and making comments itself was also a way of public participation during the Henan floods. While many news reports and social media posts were focused on what was going on in the provincial capital of Zhengzhou, the people in the more rural areas such as Weihui in Xinxiang started sounding the alarm by July 21st, pleading for netizens to pay more attention to their situation so that it would also enter the top trending lists. Sharing these posts to draw more attention to them also became a way of providing assistance.

By July 21st, half of Weibo’s top trending topics were related to the Henan floods.

Showing Support and Showing Off

Chinese netizens made a huge impact on how the Henan flood disaster was handled in the early stages, but companies in China also contributed to flooding relief efforts in many ways, while their actions simultaneously served PR goals.

On July 21st, one major company after the other announced its donation via social media. Tech giants Pinduoduo, Tencent, Meituan, Didi, and Bytedance all donated 100 million yuan ($15.4 million) each to help the rescue operations in Henan. Alibaba topped the list with a 150 million ($23 million) donation.

Besides donating 30 million yuan ($4.6 million), Chinese tech giant Huawei also sent a team of 187 engineers to provide assistance on the front line and 68 of their R&D experts worked on helping local operators in their network repair and maintenance work to ensure a smooth communication network in the disaster area.

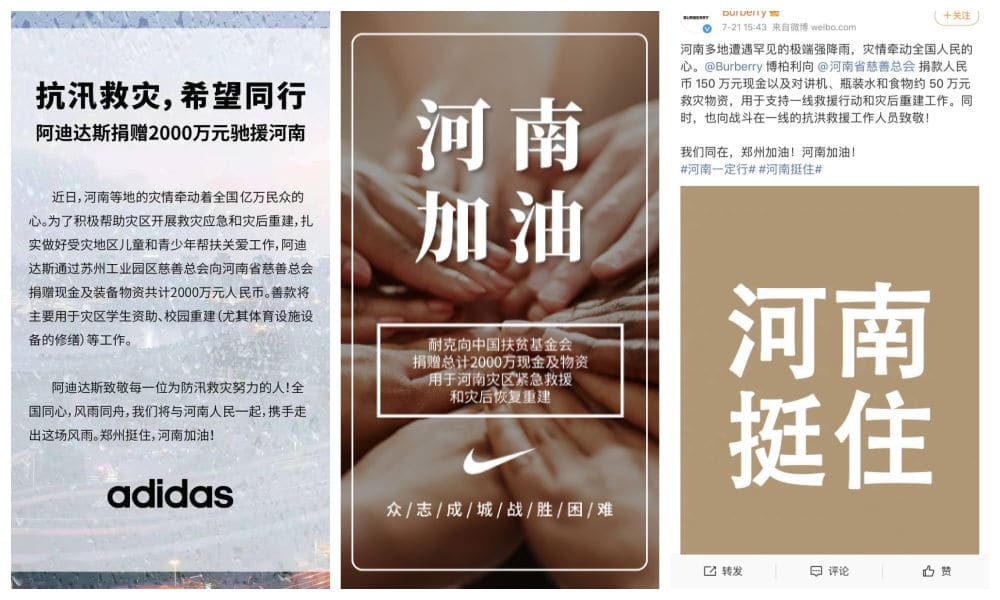

The Henan floods also provided an opportunity for Western brands in China to win back public favor. Many Western companies triggered outrage in China earlier this year over their ban on cotton from Xinjiang (link). In light of the Henan catastrophe, Nike and Adidas each contributed 20 million yuan ($3 million), Uniqlo 10 million ($1.5 million), PUMA 5 million ($773,000), Burberry 1.5 million yuan ($230,000), and Zara and H&M each donated 1 million ($155,000).

Adidas, Nike, and Burberry announcing their donations via social media.

Their contributions, however, did not seem to do much for their public image. The donations barely received media coverage, and some social media users who did know about them complained that Zara and H&M did not give enough money. There were also many netizens who praised Chinese sportswear brands for donating money and condemned Nike for giving “zero yuan,” even though the company had already announced donating 20 million yuan.

The company that really managed to win the public’s favor through their Henan donation is Erke (鸿星尔克 ), a relatively small and low-key Chinese sportswear company that seemingly was not doing too well over the past year facing great domestic competition.

When Erke donated 50 million yuan ($7.7 million) to the Henan flood relief efforts, it attracted major attention on Chinese social media. The sportswear brand donated an amount that was ten times higher than, for example, the donation made by major coffee company Starbucks.

Erke announcing its donation via social media (Weibo).

After people found out that the Erke brand donated such a high amount of money to help the people in Henan despite its own losses, its sales went through the roof – everyone wanted to support this generous ‘patriotic brand.’ While netizens rushed to the online shops selling Erke, the brand’s physical shops also ran out of products with so many people coming to buy their sportswear. Some sales assistants were moved to tears when the store suddenly filled up with customers.

People lining up at an Erke shop, photo via UDN.com.

The Erke hype even went so far that Chinese livestream sellers of Nike and Adidas notified their viewers that they actually supported the domestic Erke brand.

Adidas livestream sellers supporting Erke.

Erke profited from helping Henan, but there were also those companies that wanted to profit from the Henan floods without actually helping.

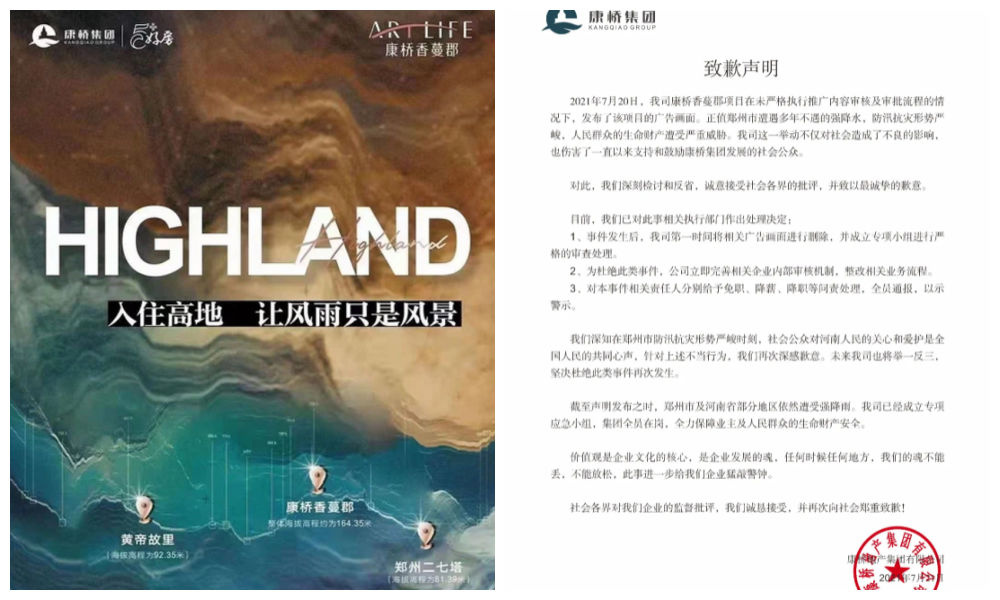

One ad by the local real estate company Kangqiao Real Estate promoting its ‘high lands’ properties led to online controversy. The Kangqiao Group poster highlighted the height advantage to its real estate locations, using the slogan: “Highland – live in the highland and only let the wind and rain be your scenery.”

The company apologized for its insensitive marketing campaign on July 21st, the hashtag (#康桥地产致歉#) received over 130 million views, but the damage to its reputation had already been done. In a similar fashion, two other companies also promoted their “safe” real estate and parking lots during the Henan floodings, with one company using a photo of a flooded car in Henan to suggest what could happen when not using their services. It led to online outrage that these companies would use such a disastrous time for their own marketing purposes.

Other examples of people using the floods for their own publicity also went trending on social media, such as a group of Chinese online influencers who came to affected areas to record themselves, making a show out of the floods (photos below).

On July 27, some online influencers even went one step further to promote their channels and boost viewership. They traveled to Weihui, one of the province’s worst affected areas, and shamelessly stole a rescue boat, and headed into the waters without actually helping anyone. The incident prevented actual aid workers from doing their job and delayed the rescue work by four hours. It caused controversy on Weibo (#网红为拍视频偷救生艇谎称去救人#), with many wondering why these people would want to profit from a situation that was still so critical.

There were also online discussions on situations in which it was less clear to what extent people were in it for ‘the show.’ Chinese celebrities Han Hong (韩红) and Wang Yibo (王一博) both traveled to the affected areas for their charity work, but they were then accused of using the disaster for their own PR benefits. Many did not agree, saying they were “moved by their patriotism.”

Official Media Promoting National Solidarity

Most hashtags, videos, and trending topics on Weibo from the early moments of the rainfall and floods were initiated by regular netizens. Many people in the affected regions posted photos and videos of the local scenes themselves.

When the cars of the Zhengzhou subway line 5 were submerged in water due to flash floods on July 20, over 500 passengers were trapped. Footage of people in the carriages standing in chest-deep water that was still rising circulated on social media as rescue efforts were underway. Some hours later, rescuers managed to get people out safely, but 14 people did not make it out alive.

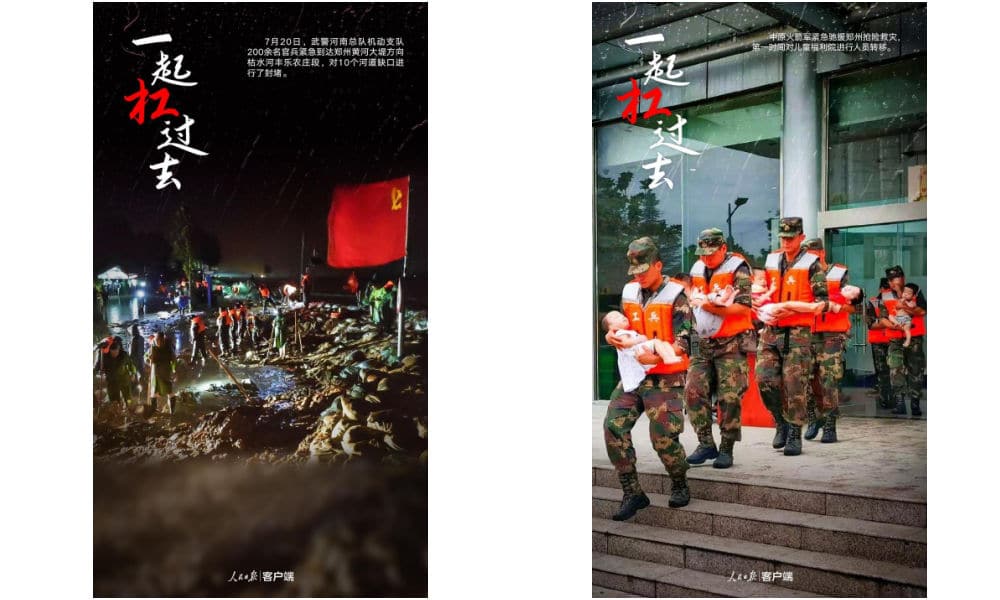

These kinds of unfolding events and tragedies were posted and reported on social media in real time by bloggers. Although official media channels and government accounts were also active in reporting incidents and releasing timely information, they soon focused on sending out a message of national unity and emphasized successful rescue operations and the competency of China’s relief efforts.

A similar approach to crisis communication on social media was seen during the outbreak of COVID19 and in other emergency situations – it is a route that has been taken for many years in the Party’s partnership with the media. In Media Politics in China (2017), author Maria Repnikova writes about the response to the Wenchuan earthquake (2008) when she points out how most official coverage concerning crisis management positively portrays the state’s rescue efforts and utilizes emotional projection of national unity and resilience, conveying an overall positive and people-centered narrative (118-121).

This patriotic discourse was also adopted in the social media coverage of the Henan floods by official channels. State media outlets were in unison in promoting hashtags such as “Stand Strong, Henan, We’re Coming” (#河南挺住我们来了#), “Zhengzhou, Hold On!” (#郑州挺住#), or “Shouldering Together with Henan” (#和河南一起扛#).

Online posters for the Henan Floods by CCTV, People’s Daily, and Xinhua.

In their news reporting, official media channels especially spotlighted people-centered stories. Some examples include the story of a 17-year-old boy who cried as he hugged the firefighter who rescued him, the news item on a 3-month old baby who was pulled from the ruins of a collapsed house in Xingyang, or the account of a Zhengzhou policeman who was so dedicated to his work that he hadn’t returned home in over 30 hours.

By July 21st, official Party newspaper People’s Daily had launched a hashtag titled “Touching Scenes of People Helping Each Other” (#河南暴雨中的感人互助画面#), which showed photos and videos of citizens working together in rescuing people from the water.

Another Weibo hashtag was titled “The Power of China during the Henan Rainstorms” (#河南暴雨中的中国力量#), which focused on the solidarity and compassion of the thousands of volunteers and rescue workers, stressing the idea that the people of China are able to get through difficulties together.

“We can get through this together,” online posters by People’s Daily.

The main message that is propagated by Chinese official media and government on social media is one that resonates with the general Weibo audience. Standing together with Henan and uniting in times of disaster is a sentiment that is strongly supported, not just by official channels, but by netizens, celebrities, and companies alike.

As the floods and relief efforts are still continuing in various parts of Henan Province, the messages of support and online assistance are ongoing. “Come on, Henan!” is the slogan that is sent out everywhere on Weibo, with people staying positive: “We can do this together. Everything is going to be alright.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

References:

Levin, Dan. 2013. “Social Media in China Fuel Citizen Response to Quake.” New York Times, May 11 https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/12/world/asia/quake-response.html [7.30.21].

Repnikova, Maria. 2017. Media Politics in China: Improvising Power under Authoritarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

This text was written for Goethe-Institut China under a CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE license (Creative Commons) as part of a monthly column in collaboration with What’s On Weibo.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

Published

2 months agoon

June 8, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

JD.com’s 618 shopping festival is driving down book prices to such an extent that it has prompted a boycott by Chinese publishers, who are concerned about the financial sustainability of their industry.

When June begins, promotional campaigns for China’s 618 Online Shopping Festival suddenly appear everywhere—it’s hard to ignore.

The 618 Festival is a product of China’s booming e-commerce culture. Taking place annually on June 18th, it is China’s largest mid-year shopping carnival. While Alibaba’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival has been taking place on November 11th since 2009, the 618 Festival was launched by another Chinese e-commerce giant, JD.com (京东), to celebrate the company’s anniversary, boost its sales, and increase its brand value.

By now, other e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Pinduoduo have joined the 618 Festival, and it has turned into another major nationwide shopping spree event.

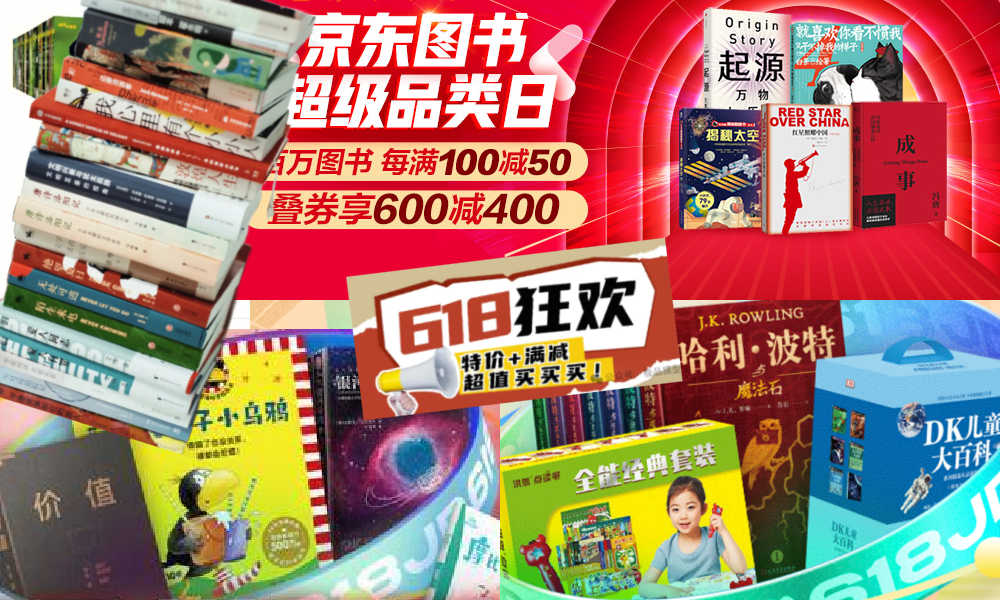

For many book lovers in China, 618 has become the perfect opportunity to stock up on books. In previous years, e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Dangdang (当当) would roll out tempting offers during the festival, such as “300 RMB ($41) off for every 500 RMB ($69) spent” or “50 RMB ($7) off for every 100 RMB ($13.8) spent.”

Starting in May, about a month before 618, the largest bookworm community group on the Douban platform, nicknamed “Buying Like Landsliding, Reading Like Silk Spinning” (买书如山倒,看书如抽丝), would start buzzing with activity, discussing book sales, comparing shopping lists, or sharing views about different issues.

Social media users share lists of which books to buy during the 618 shopping festivities.

This year, however, the mood within the group was different. Many members posted that before the 618 season began, books from various publishers were suddenly taken down from e-commerce platforms, disappearing from their online shopping carts. This unusual occurrence sparked discussions among book lovers, with speculations arising about a potential conflict between Chinese publishers and e-commerce platforms.

A joint statement posted in May provided clarity. According to Chinese media outlet The Paper (@澎湃新闻), eight publishers in Beijing and the Shanghai Publishing and Distribution Association, which represent 46 publishing units in Shanghai, issued a statement indicating they refuse to participate in this year’s 618 promotional campaign as proposed by JD.com.

The collective industry boycott has a clear motivation: during JD’s 618 promotional campaign, which offers all books at steep discounts (e.g., 60-70% off) for eight days, publishers lose money on each book sold. Meanwhile, JD.com continues to profit by forcing publishers to sell books at significantly reduced prices (e.g., 80% off). For many publishers, it is simply not sustainable to sell books at 20% of the original price.

One person who has openly spoken out against JD.com’s practices is Shen Haobo (沈浩波), founder and CEO of Chinese book publisher Motie Group (磨铁集团). Shen shared a post on WeChat Moments on May 31st, stating that Motie has completely stopped shipping to JD.com as it opposes the company’s low-price promotions. Shen said it felt like JD.com is “repeatedly rubbing our faces into the ground.”

Nevertheless, many netizens expressed confusion over the situation. Under the hashtag topic “Multiple Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Book Promotions” (#多家出版社抵制618图书大促#), people complained about the relatively high cost of physical books.

With a single legitimate copy often costing 50-60 RMB ($7-$8.3), and children’s books often costing much more, many Chinese readers can only afford to buy books during big sales. They question the justification for these rising prices, as books used to be much more affordable.

Book blogger TaoLangGe (@陶朗歌) argues that for ordinary readers in China, the removal of discounted books is not good news. As consumers, most people are not concerned with the “life and death of the publishing industry” and naturally prefer cheaper books.

However, industry insiders argue that a “price war” on books may not truly benefit buyers in the end, as it is actually driving up the prices as a forced response to the frequent discount promotions by e-commerce platforms.

China News (@中国新闻网) interviewed publisher San Shi (三石), who noted that people’s expectations of book prices can be easily influenced by promotional activities, leading to a subconscious belief that purchasing books at such low prices is normal. Publishers, therefore, feel compelled to reduce costs and adopt price competition to attract buyers. However, the space for cost reduction in paper and printing is limited.

Eventually, this pressure could affect the quality and layout of books, including their binding, design, and editing. In the long run, if a vicious cycle develops, it would be detrimental to the production and publication of high-quality books, ultimately disappointing book lovers who will struggle to find the books they want, in the format they prefer.

This debate temporarily resolved with JD.com’s compromise. According to The Paper, JD.com has started to abandon its previous strategy of offering extreme discounts across all book categories. Publishers now have a certain degree of autonomy, able to decide the types of books and discount rates for platform promotions.

While most previously delisted books have returned for sale, JD.com’s silence on their official social media channels leaves people worried about the future of China’s publishing industry in an era dominated by e-commerce platforms, especially at a time when online shops and livestreamers keep competing over who has the best book deals, hyping up promotional campaigns like ‘9.9 RMB ($1.4) per book with free shipping’ to ‘1 RMB ($0.15) books.’

This year’s developments surrounding the publishing industry and 618 has led to some discussions that have created more awareness among Chinese consumers about the true price of books. “I was planning to bulk buy books this year,” one commenter wrote: “But then I looked at my bookshelf and saw that some of last year’s books haven’t even been unwrapped yet.”

Another commenter wrote: “Although I’m just an ordinary reader, I still feel very sad about this situation. It’s reasonable to say that lower prices are good for readers, but what I see is an unfavorable outlook for publishers and the book market. If this continues, no one will want to work in this industry, and for readers who do not like e-books and only prefer physical books, this is definitely not a good thing at all!”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese Sun Protection Fashion: Move over Facekini, Here’s the Peek-a-Boo Polo

From facekini to no-face hoodie: China’s anti-tan fashion continues to evolve.

Published

2 months agoon

June 6, 2024

It has been ten years since the Chinese “facekini”—a head garment worn by Chinese ‘aunties’ at the beach or swimming pool to prevent sunburn—went international.

Although the facekini’s debut in French fashion magazines did not lead to an international craze, it did turn the term “facekini” (脸基尼), coined in 2012, into an internationally recognized word.

The facekini went viral in 2014.

In recent years, China has seen a rise in anti-tan, sun-protection garments. More than just preventing sunburn, these garments aim to prevent any tanning at all, helping Chinese women—and some men—maintain as pale a complexion as possible, as fair skin is deemed aesthetically ideal.

As temperatures are soaring across China, online fashion stores on Taobao and other platforms are offering all kinds of fashion solutions to prevent the skin, mainly the face, from being exposed to the sun.

One of these solutions is the reversed no-face sun protection hoodie, or the ‘peek-a-boo polo,’ a dress shirt with a reverse hoodie featuring eye holes and a zipper for the mouth area.

This sun-protective garment is available in various sizes and models, with some inspired by or made by the Japanese NOTHOMME brand. These garments can be worn in two ways—hoodie front or hoodie back. Prices range from 100 to 280 yuan ($13-$38) per shirt/jacket.

The no-face hoodie sun protection shirt is sold in various colors and variations on Chinese e-commerce sites.

Some shops on Taobao joke about the extreme sun-protective fashion, writing: “During the day, you don’t know which one is your wife. At night they’ll return to normal and you’ll see it’s your wife.”

On Xiaohongshu, fashion commenters note how Chinese sun protective clothing has become more extreme over the past few years, with “sunburn protection warriors” (防晒战士) thinking of all kinds of solutions to avoid a tan.

Although there are many jokes surrounding China’s “sun protection warriors,” some people believe they are taking it too far, even comparing them to Muslim women dressed in burqas.

Image shared on Weibo by @TA们叫我董小姐, comparing pretty girls before (left) and nowadays (right), also labeled “sunscreen terrorists.”

Some Xiaohongshu influencers argue that instead of wrapping themselves up like mummies, people should pay more attention to the UV index, suggesting that applying sunscreen and using a parasol or hat usually offers enough protection.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?