China Insight

100 Terms the Communist Party Wants You to Know for the 19th National Congress

100 “must-know” terms for the 19th National Congress, propagated by People’s Daily.

Published

8 years agoon

These are the 100 terms to know for the 19th CPC National Congress – propagated by People’s Daily, the mouthpiece of China’s ruling Communist Party, on Weibo.

It is the week of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), better known as the “19th Party Congress.” This meeting, that takes place from October 18 to October 24, is a major event that takes place every five years.

On Chinese social media, Communist Party newspaper People’s Daily (@人民日报) presented a vocabulary list for people to know before the huge political event.

During the 19th Party Congress approximately 2280 delegates from across the nation officially come together to select the party’s top leadership for the next five years. The event is also called a “celebration of decisions that have already been taken,” as the key points of the meeting have mostly already been settled behind closed doors.

It is these key decisions for China that will be discussed during the CPC National Congress and then officially announced, representing “new governance concepts, thoughts and strategies proposed by the CPC Central Committee with Xi Jinping at its core” (Xinhua).

In a recent report by APCO Worldwide, Gary Li summarizes what to look out for during the 19th National Congress, writing that it is likely for President Xi Jinping to “consolidate his power further by making changes to the party apparatus,” influencing regulators in various sectors from finance to trade and cybersecurity.

Posting the 9-page list of a total of 100 terms on Weibo, People’s Daily (@人民日报) writes:

“Study time! We want to teach you the translation of 100 hot terms for the 19th CPC National Congress (..) Do you know how to say these things in English? This is how to avoid using Chinglish and to express [these terms] in a more authentic way. They are all useful for CET-4 & CET-6 [national English level tests in China] and other exams. Let’s learn these!”

By October 18, the list was shared 19000 times on Weibo and received many comments.

One netizen said: “With these 100 words you can understand a new China.” Others complained that they still think the English translation of these Chinese terms “sounds like Chinglish.”

Relevant Words: Policy Trends & Digital Focus

The vocabulary list, which was selected from China Daily‘s “Little Red Book of Hot Words” (热词红宝书), is an interesting combination of terms that says a lot about the focal points of the National Congress and the trends that are emphasized for the coming five years.

In the recent APCO report, Gary Li mentions Ideological Tightening as a crucial policy trend. This promotion of “Chinese values” is clearly visible in the vocabularly list, that includes terms such as “the Chinese Dream” (中国梦), “Stay true to the mission” (不忘初心), and “cultural confidence” (文化自信).

Another important policy trend on the government agenda is Anti-Corruption, which is represented by the term “anti-corruption TV series” (反腐剧).

The list also includes some Internet slang terms such as “give a like” (点赞) or “phubber”/”bowed head clan” (低头族), referring to people who constantly look down to their smartphone.

It also includes a catchphrase that became especially popular on Chinese social media in 2016 when it was used by Chinese swimming champion Fu Yuanhui during an interview about her winning medal during the Olympics – (“用了洪荒之力”), which can be translated as “I’ve used my primeval powers!”, basically meaning “to give one’s full play.”

Swimmer Fu Yuanhui went viral in 2016 when she introduced a new catchphrase that is still a hot online sentence.

The inclusion of some typical internet catchphrases is especially noteworthy because in 2014, Chinese state media published that programs and commercials should not use Internet language to preserve traditional expressions.

The entire list has a clear Digital Focus when it comes to different industries, including government, media, finance, and traveling, introducing words such as “in-flight Wifi services” (空中上网服务), “face scan payment” (扫脸支付), 5G era (5G时代), and taxi-hailing app (打车软件).

The Belt and Road initiative and China’s role in the world is an important point on this year’s agenda.

The list also includes words that emphasize the Belt and Road Initiative and China-centric Relations for Economy and Trade, such as the “New type of major-power relationship” (新型大国关系).

The List: 100 Hot Words for the 19th National Congress

This is the full list of the 100 terms as shared by the People’s Daily through screenshots, typed out by What’s on Weibo. The pinyin and tones are also provided by What’s on Weibo.

1. 中国梦

Zhōngguó mèng

China dream

2. 不忘初心

Bù wàng chūxīn

Stay true to the mission

3. 两个一百年

Liǎng gè yībǎi nián

Two centenary goals

4. 新常态

Xīn chángtài

New normal

5. 中国制造2025

Zhōngguó zhìzào 2025

Made in China 2025

6. “双一流”

Shuāng yīliú

Double First-Class initiative

7. 工匠精神

Gōngjiàng jīngshén

Craftsmanship spirit

8. 中国天眼:500米口径球面射电望远镜(FAST)

Zhōngguó tiānyǎn:500 Mǐ kǒujìng qiúmiàn shèdiàn wàngyuǎnjìng (FAST)

China’s Eye of Heaven: The 500-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope

9. 歼-20战斗机

Jiān-20 zhàndòujī

J-20 Stealth Fighter

10. 国产航母

Guóchǎn hángmǔ

Domestically built aircraft carrier

11. 国产客机

Guóchǎn kèjī

Homemade passenger jet

12. 可燃冰试采

Kěrán bīng shì cǎi

Sampling of combustible ice

13. 量子卫星”墨子号”

Liàngzǐ wèixīng “mò zi hào”

Quantum satellite “Micius”

14. 北斗卫星导航系统

Běidǒu wèixīng dǎoháng xìtǒng

Beidou navigation system

15. 风云四号A星卫星

Fēngyún sì hào A xīng wèixīng

Fengyun-4A satellite

16. 重型运载火箭

Zhòngxíng yùnzài huǒjiàn

Heavy-lift Carrier Rocket

17. 沪港通

Hù gǎng tōng

Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect

18. 深港通

Shēn gǎng tōng

Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect

19. 京津冀一体化

Jīng jīn jì yītǐ huà

Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei integration

20. 雄安新区

Xióng ān xīnqū

Xiong’an New Area

21. 自贸实验区

Zì mào shíyàn qū

Pilot Free Trade Zones

22. 医疗改革

Yīliáo gǎigé

Medical Reform

23. 供给侧改革

Gōngjǐ cè gǎigé

Supply-side reform

24. 扫脸支付

Sǎo liǎn zhīfù

Face scan payment

25. 二维码支付

Èr wéi mǎ zhīfù

Two-dimensional barcode payment

26. 人工智能

Réngōng zhìnéng

Artificial intelligence

27. 虚拟现实

Xūnǐ xiànshí

Virtual reality

28. 5G时代

5G shídài

5G era

29. 分享经济

Fēnxiǎng jīngjì

Sharing economy

30. 互联网金融

Hùliánwǎng jīnróng

Online finance

31. 亚投行

Yà tóuháng

Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank

32. 低碳城市

Dī tàn chéngshì

Low-carbon cities

33. 一小时通通勤圈

Yī xiǎoshí tōng tōngqín quān

One-hour commuting circle

34. 蓝色经济

Lán sè jīngjì

Blue economy

35. 纵向横向经济轴带

Zòngxiàng héngxiàng jīngjì zhóu dài

North-south and east-west intersecting economic belts

36. 众创、众包、众扶、众筹

Zhòng chuàng, zhòng bāo, zhòng fú, zhòng chóu

Crowd innovation, crowdsourcing,crowd support and crowdfunding.

37. 战略性新兴产业

Zhànlüè xìng xīnxīng chǎnyè

Emerging sectors of strategic importance

38. 香港回归祖国20周年

Xiānggǎng huíguī zǔguó 20 zhōunián

The 20th anniversary of Hong-Kong’s return to China

39. 点赞

Diǎn zàn

Give a like

40.自媒体

Zì méitǐ

We-Media

41. 实名认证

Shímíng rènzhèng

Real name authentication

42. 精准扶贫

Jīngzhǔn fúpín

Targeted poverty reduction

43. 精准医疗

Jīngzhǔn yīliáo

Precision medicine

44. 利益共同体

Lìyì gòngtóngtǐ

Community of shared interests

45. 轨道交通

Guǐdào jiāotōng

Rail traffic

46. 动车

Dòngchē

Bullet train

47. 城际列车

Chéng jì lièchē

Inter-city transport

48. “一带一路”倡议

“Yīdài yīlù”chàngyì

Belt and Road Initiative

49. “丝绸之路经济带”

“Sīchóu zhī lù jīngjì dài”

The Silk Road Economic Belt

50. 21世纪海上丝绸之路

21 Shìjì hǎishàng sīchóu zhī lù

21st- Century Maritime Silk Road

51. 古丝绸之路

Gǔ sīchóu zhī lù

The Ancient Silk Road

52. 互联互通

Hùlián hùtōng

Establish and Strengthen Partnerships/Connectivity

53. 文化自信

Wénhuà zìxìn

Cultural confidence

54. 新型大国关系

Xīnxíng dàguó guānxì

New type of major-power relationship

55. 可替代能源汽车

Kě tìdài néngyuán qìchē

Alternative energy vehicle

56. 可载人无人机

Kě zài rén wú rén jī

Passenger-carrying drone

57. 空中上网服务

Kōngzhōng shàngwǎng fúwù

In-flight Wifi services

58. 海外购外

Hǎiwài gòu wài

Overseas shopping representative

59. 海淘

Hǎi táo

Cross-border online shopping

60. 多次往返签证

Duō cì wǎngfǎn qiānzhèng

Multiple entry visa

61. 散客

Sǎn kè

Individual traveler

62. 自由行

Zìyóu xíng

Independent travel

63. 跟团游

Gēn tuán yóu

Package tour

64.深度游

Shēndù yóu

In-depth travel

65. 自驾游

Zìjià yóu

Self-driving tours

66. 免税店

Miǎnshuì diàn

Duty-free store

67. 无现金支付

Wú xiànjīn zhīfù

Cashless payment

68. 旺季

Wàngjì

Peak season

69. 淡季

Dànjì

Offseason

70. 反腐剧

Fǎnfǔ jù

Anti-corruption TV series

71. 合拍片

Hépāi piàn

Co-production

72. 打车软件

Dǎchē ruǎnjiàn

Taxi-hailing app

73. 代驾服务业

Dài jià fúwù yè

Designated driver business

74. 单双号银行

Dān shuāng hào yínháng

Traffic restrictions based on even- and odd-numbered license plates

75. 共享汽车

Gòngxiǎng qìchē

Car-sharing

76. 绿色金融改革新试验区

Lǜsè jīnróng gǎigé xīn shìyàn qū

Pilot zones for green finance reform and innovations

77. 超国民待遇

Chāo guómín dàiyù

Super-national treatment

78. 现代医院管理制度

Xiàndài yīyuàn guǎnlǐ zhìdù

Modern hospital management system

79. 机遇之城

Jīyù zhī chéng

Cities of opportunities

80.直播经济

Zhíbò jīngjì

Live stream economy

81. 互联网+政府服务

Hùliánwǎng +zhèngfǔ fúwù

Internet Plus government services

82. 创新型政府

Chuàngxīn xíng zhèngfǔ

Pro-innovation government

83. 无人机紧急救援队

Wú rén jī jǐnjí jiùyuán duì

UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) emergency rescue team

84. 二孩经济

Èr hái jīngjì

Second-child economy

85.父亲假;陪产假

Fùqīn jià; péi chǎnjià

Paternity leave

86. 带薪休假

Dài xīn xiūjià

Paid leave

87. 低头族

Dītóu zú

Phubber

88. 副中心

Fù zhōngxīn

Subcenter

89. 用了洪荒之力

Yòngle hónghuāng zhī lì

Give one’s full play

90. 营改增

Yíng gǎi zēng

Replace business tax with value-add tax (VAT)

91. 创新型人才

Chuàngxīn xíng réncái

Innovative talent

92. 积分落户制度

Jīfēn luòhù zhìdù

Points-based hukou system

93. 混合所有制改革

Hùnhé suǒyǒuzhì gǎigé

Mixed-ownership reform

94. 税收减免

Shuìshōu jiǎnmiǎn

Tax reduction and exemption

95. 生态保护红线

Shēngtài bǎohù hóngxiàn

Ecological wealth

96. 网约车

Wǎng yuē chē

Online car-hailing

97. 宜居城市

Yí jū chéngshì

Habitable city

98. 移动支付

Yídòng zhīfù

Mobile payment

99. 电子竞技

Diànzǐ jìngjì

E-sports

100. 双创人才

Shuāng chuàng réncái

Innovative and entrepreneutrial talent

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform resurfaces in Africa, a new winter hotspot, why Chinese elites ‘run’ to Tokyo, and more.

Published

2 months agoon

November 21, 2025

🌊 Signals — Week 47 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China, Signals highlights slower trends and online currents behind the daily scroll. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Different from the China Trend Watch (check the latest one here if you missed it), this edition, part of the new Signals series, is about the slower side of China’s social media: the recurring themes and underlying shifts that signal broader trends beyond the quick daily headlines. Together with the deeper dives, the three combined aim to give you clear updates and a fuller overview of what’s happening in China’s online conversations & digital spaces.

For the coming two weeks, I’ll be traveling from Beijing to Chongqing and beyond (more on that soon) so please bear with me if my posting frequency dips a little. I’ll be sure to pick it up again soon and will do my best to keep you updated along the way. In the meantime, if you know of a must-try hotpot in Chongqing, please do let me know.

In this newsletter: Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform in Angola, a new winter hotspot, discussions on what happens to your Wechat after you die, why Chinese elites rùn to Tokyo, and more. Let’s dive in.

- 💰 The richest woman in China, according to the latest list by Hurun Research Institute, is the “queen of pharmaceuticals” Zhong Huijuan (钟慧娟) who has accumulated 141 billion yuan (over 19 billion USD). Women account for over 22% of Chinese billionaires (those with more than 5 billion RMB), underscoring China’s globally leading position in producing wealthy female entrepreneurs.

- 🧩 What happens to your WeChat after you die? A user who registered for NetEase Music with a newly reassigned phone number unexpectedly gained access to the late singer Coco Lee’s (李玟) account, as the number had originally belonged to her. The incident has reignited debate over how digital accounts should be handled after death, prompting platforms like NetEase and Tencent to reconsider policies on long-inactive accounts and take stronger measures to protect them.

- 📱 Although millions of viewers swoon over micro-dramas with fantasy storylines where rich, powerful men win over the “girl next door” through money and status, Chinese regulators are now stepping in to curb exaggerated plots featuring the so-called “dominant CEO” (霸道总裁) archetype, signaling stricter oversight for the booming short drama market.

- ☕ A popular Beijing coffee chain calling itself “People’s Cafe” (人民咖啡馆), with its style and logo evoking nationalist visual nostalgia, has changed its name after facing criticism for building its brand – including pricey coffee and merchandise – on Mao era and state-media political connotations. The cafe is now ‘Yachao People’s Cafe’ (要潮人民咖啡馆).

- 👀 Parents were recently shocked to see erotic ads appear on the Chinese nursery rhymes and children’s learning app BabyBus (宝宝巴士), which is meant for kids ages 0–8. BabyBus has since apologized, but the incident has sparked discussions about how to keep children safe from such content.

- 🧧The 2026 holiday schedule has continued to be a big topic of conversation as it includes a 9-day long Spring Festival break (from February 15 to February 23), making it the longest Lunar New Year holiday on record. The move not only gives people more time for family reunions, but also gives a huge boost to the domestic travel industry.

Hasan Piker’s Chinese Tour & The US–China Content Honeymoon

Livestreamer Hasan Piker during his visit to Tiananmen Square flag-rising ceremony.

It’s not time for the end-of-year overviews just yet – but I’ll already say that 2025 was the US–China ‘honeymoon’ year for content creation. It’s when China became “cool,” appealing, and eye-grabbing for young Western social media users, particularly Americans. The recent China trip of the prominent American online streamer Hasan Piker fits into that context.

This left-wing political commentator also known as ‘HasanAbi’ (3 million followers on Twitch, recently profiled by the New York Times) arrived in China for a two-week trip on November 11.

Piker screenshot from the interview with CGTN, published on CGTN.

His visit has been controversial on English-language social media, especially because Piker, known for his criticism of America (which he calls imperialist), has been overly praising China: calling himself “full Chinese,” waving the Chinese flag, joining state media outlet CGTN for an interview on China and the US, and gloating over a first-edition copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao (the Little Red Book). He portrays China as heavily misrepresented in the West and as a country the United States should learn from.

Hasan Piker did an interview with CGTN, posing with Li Jingjing 李菁菁.

During his livestreaming tour, Hasan, who is nicknamed “lemonbro” (柠檬哥) by Chinese netizens, also joined Chinese platforms Bilibili and Xiaohongshu.

But despite all the talk about Piker in the American online media sphere, online conversations, clicks, and views within China are underwhelming. As of now, he has around 24,000 followers on Bilibili, and he’s barely a topic of conversation on mainstream feeds.

Piker’s visit stands in stark contrast to that of American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins), who toured China in March. With lengthy livestreams from Beijing to Chongqing, his popularity exploded in China, where he came to be seen by many as a representative of cultural diplomacy.

IShowspeed in China, March 2025.

IShowSpeed’s success followed another peak moment in online US–China cultural exchange. In January 2025, waves of foreign TikTok users and popular creators migrated to the Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu amid the looming TikTok ban.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against Trump and US policies. In a playful act of political defiance, they downloaded Xiaohongshu to show they weren’t scared of government warnings about Chinese data collection. (For clarity: while TikTok is a made-in-China app, it is not accessible inside mainland China, where Douyin is the domestic version run by the same parent company).

The influx of foreigners — who were quickly nicknamed “TikTok refugees” — soon turned into a moment of cultural celebration. As American creators introduced themselves, Chinese users welcomed them warmly, eager to practice English and teach newcomers how to navigate the app. Discussions about language, culture, and societal differences flourished. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor. It was a rare moment of social media doing what we hope it can do: connect people, build bridges, and replace prejudice with curiosity.

Some of that same enthusiasm was also visible during IShowSpeed’s China tour. Despite the tour inevitably getting entangled with political and commercial interests, much of it was simply about an American boy swept up in the high energy of China’s vibrant cities and everything they offer.

Different from IShowSpeed, who is known for his meme-worthy online presence, Piker is primarily known for his radical political views. His China enthusiasm feels driven less by cultural curiosity and more by his critique of America.

Because of his stances — such as describing the US as a police state — it’s easy for Western critics to accuse him of hypocrisy in praising China, especially after a brief run-in with security police while livestreaming at Tiananmen Square.

Seen in broader context, Piker’s China trip reflects a shift in how China is used in American online discourse.

Before, it was Chinese ‘public intellectuals’ (公知) who praised the US as a ‘lighthouse country’ (灯塔国), a beacon of democracy, to indirectly critique China and promote a Western modernization model. Later, Chinese online influencers showcased their lives abroad to emphasize how much ‘brighter the moon’ was outside China.

In the post-Covid years, the current reversed: Western content creators, from TikTok influencers to political commentators, increasingly use China to make arguments that are fundamentally about America.

Between these cycles, authentic cultural curiosity gets pushed to the sidelines. The TikTok-refugee moment in early January may have been the closest we’ve come in years: a brief window where Chinese and American users met each other with curiosity, camaraderie, and creativity.

Hasan’s tour, in contrast, reflects a newer phase, one where China is increasingly used as a stage for Western political identity rather than a complex and diverse country to understand on its own terms. I think the honeymoon phase is over.

“Liu Sihan, Your School Uniform Ended Up in Angola”: China’s Second-Hand Clothing in Africa

A Chinese school uniform went viral after a Chinese social media user spotted it in Angola.

“Liu Sihan, your schooluniform is hot in Africa” (刘思涵你的校服在非洲火了) is a sentence that unexpectedly trended after a Chinese blogger named Xiao Le (小乐) shared a video of a schoolkid in Angola wearing a Chinese second-hand uniform from Qingdao Xushuilu Primary School, that had the nametag Liu Sihan on it.

The topic sparked discussions about what actually happens to clothing after it’s donated, and many people were surprised to learn how widely Chinese discarded clothing circulates in parts of Africa.

Liu Sihan’s mother, whose daughter is now a 9th grader in Qingdao, had previously donated the uniform to a community clothing donation box (社区旧衣回收箱) after Liu outgrew it. She intended it to help someone in need, never imagining it to travel all the way to Africa.

In light of this story, one netizen shared a video showing a local African market selling all kinds of Chinese school items, including backpacks, and people wearing clothing once belonging to workers for Chinese delivery platforms. “In Africa, you can see school uniforms from all parts of China, and even Meituan and Eleme outfits,” one blogger wrote.

When it comes to second-hand clothing trade, we know much more about Europe–Africa and US–Africa flows than about Chinese exports, and it seems there haven’t been many studies on this specific topic yet. Still, alongside China’s rapid economic transformations, the rise of fast fashion, and the fact that China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of textiles, the country now has an enormous abundance of second-hand clothing.

According to a 2023 study by Wu et al. (link), China still has a long way to go in sustainable clothing disposal. Around 40% of Chinese consumers either keep unwanted clothes at home or throw them away.

But there may be a shift underway. Donation options are expanding quickly, from government bins to brand programs, and from second-hand stores to online platforms that offer at-home pickup.

Chinese social media users posting images of school/work uniforms from China worn by Africans.

As awareness grows around the benefits of donating clothing (reducing waste, supporting sustainability, and the emotional satisfaction of giving), donation rates may rise significantly. The story of Liu Sihan’s uniform, which many found amusing, might even encourage more people to donate. And if that happens, scenes of African children (and adults) wearing Chinese-donated clothes may become much more common than they now are.

Laojunshan: New Hotspot in Cold Winter

Images from Xiaohongshu, 背包里的星子, 旅行定制师小漾

Go to Zibo for BBQ, go to Tianshui for malatang, go to Harbin for the Ice Festival, cycle to Kaifeng for soup dumplings, or head to Dunhuang to ride a camel — over recent years, a number of Chinese domestic destinations have turned into viral hotspots, boosted by online marketing initiatives and Xiaohongshu influencers.

This year, Laojunshan is among the places climbing the trending lists as a must-visit spot for its spectacular snow-covered landscapes that remind many of classical Chinese paintings. Laojunshan (老君山), a scenic mountain in Henan Province, is attracting more domestic tourists for winter excursions.

Xiaohongshu is filled with travel tips: how to get there from Luoyang station (by bus), and the best times of day to catch the snow in perfect light (7–9 AM or around 6–6:30 PM).

With Laojunshan, we see a familiar pattern: local tourism bureaus, state media, and influencers collectively driving new waves of visitors to the area, bringing crucial revenue to local industries during what would otherwise be slower winter months.

WeChat New Features & Hong Kong Police on Douyin

🟦 WeChat has been gradually rolling out a new feature that allows users to recall a batch of messages all at once, which saves you the frantic effort of deleting each message individually after realizing you sent them to the wrong group (or just regret a late-night rant). Many users are welcoming the update, along with another feature that lets you delete a contact without wiping the entire chat history. This is useful for anyone who wants to preserve evidence of what happened before cutting ties.

🟦The Hong Kong Police Force recently celebrated its two-year anniversary on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), having accumulated nearly 5 million followers during that time. To mark the occasion, they invited actor Simon Yam to record a commemorative video for their channel (@香港警察). The presence of the Hong Kong Police on the Chinese app — and the approachable, meme-friendly way they’ve chosen to engage with younger mainland audiences — is yet another signal of Hong Kong institutions’ strategic alignment with mainland China’s digital infrastructure, a shift that has been gradually taking place. The anniversary video proved popular on Douyin, attracting thousands of likes and comments.

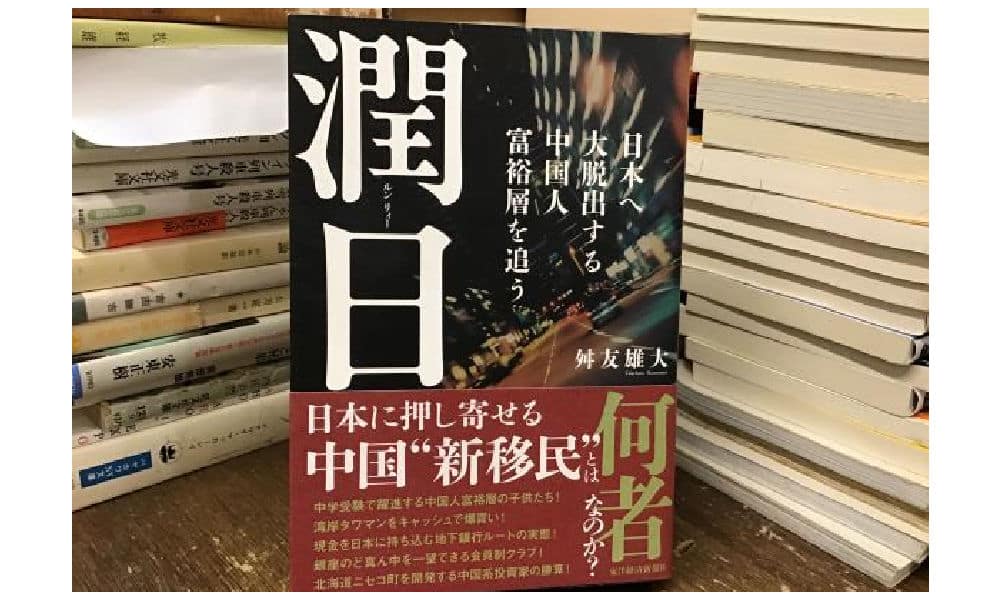

Why Chinese Elite Rùn to Japan (by ChinaTalk)

Over the past week, Japan has been trending every single day on Chinese social media in light of escalating bilateral tensions after Japanese PM Takaichi made remarks about Taiwan that China views as a direct military threat. The diplomatic freeze is triggering all kinds of trends, from rising anti-Japanese sentiment online and a ban on Japanese seafood imports to Chinese authorities warning citizens not to travel to Japan.

You’d think Chinese people would want to be anywhere but Japan right now — but the reality is far more nuanced.

In a recent feature in ChinaTalk, Jordan Schneider interviewed Japanese journalist & researcher Takehiro Masutomo (舛友雄大) who has just published a book about Japan’s new Chinese diaspora, explaining what draws Chinese dissidents, intellectuals, billionaires, and middle-class families to Tokyo.

The book is titled Run Ri: 潤日 Following the Footsteps of Elite Chinese Escaping to Japan (only available in Japanese and Traditional Chinese for now). (The word Rùn 润/潤, by the way, is Chinese online slang and meme expresses the desire to escape the country.)

A very interesting read on how Chinese communities are settling in Japan, a place they see as freer than Hong Kong and safer than the U.S., and one they’re surprisingly optimistic about — even more so than the Japanese themselves.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China Signals. For fast-moving trends and deeper dives, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you just so happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

A small housekeeping note:

This Eye on Digital China newsletter is co-published for subscribers on both Substack and the main site. If you’re registered on both platforms, you’ll receive duplicate emails — so if that bothers you, please pick your preferred platform and unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Insight

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

“You think we’re scared of you? It’s not like we haven’t been to jail before.”

Published

6 months agoon

August 6, 2025

These days have been filled with tension and anger in the city of Jiangyou (江油市), Sichuan, after a rare, large-scale protest broke out following public outrage over a severe bullying incident and how it was handled.

The bullying incident at the center of this story happened outside school premises in Mianyang on the afternoon of July 22. Footage of the assault, recorded by bystanders at the scene, began circulating widely online on August 2, sparking widespread outrage among concerned netizens, many of them worried parents.

The violent altercation involved three girls between the ages of 13 and 15 who ganged up on another minor, a 14-year-old girl named Lai (赖).

After Lai and a 15-year-old girl named Liu (刘) reportedly had a dispute, Liu gathered two of her friends—the 13-year-old also named Liu (刘) and a 14-year-old named Peng (彭)—to gang up on Lai.

The three underage girls lured Lai to an abandoned building, where they subjected her to hours of verbal and physical violence. The footage showed how they took turns in kicking, slapping, and pushing her.

At one point, after Lai said she would call the police, one of the bullies yelled: “You think we’re scared of you? It’s not like we haven’t been to jail before. I’ve been in more than ten times—it doesn’t even take 20 minutes to get out” (“你以为我们会怕你吗?又不是没进去过,我都进去十多次了,没二十分钟就出来了”).

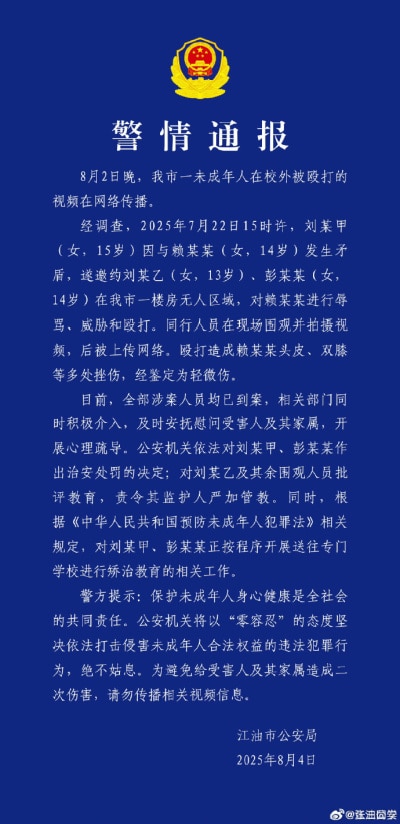

That same night, the incident was reported to police. It took authorities until August 2 to bring in all involved parties for questioning, and a police report was issued on the morning of Monday, August 4.

Police report by Jiangyou Public Security Bureau, confirming the details of the incident and the (legal) consequences for the attackers.

Two of the girls (the 15- and 14-year-old) were given administrative penalties and will be sent to a specialized correctional school. The younger Liu and other bystanders were formally reprimanded.

“Parents Speak Out for the Bullied Girl”

The way the incident was handled—not just the relatively late official report, but mostly the perceived lenient punishment—triggered anger online.

Many people who had seen the video responded emotionally and felt that the underage girls should be stripped of their rights to take their exams, and that the bullying incident should forever haunt them in the same way it will undoubtedly haunt their victim.

Especially the phrase “It’s not like I haven’t been taken in [to jail] before” struck a chord, as it showed just how calculated the bullies were—and how, by counting on the leniency of the Chinese judicial system for minors, they made the system complicit in their determination to turn those hours into a living hell for Lai.

China has been dealing with an epidemic of school violence for years. In 2016, Chinese netizens were already urging authorities to address the problem of extreme bullying in schools, partly because minors under the age of 16 rarely face criminal punishment for their actions.

Since 2021, children between the ages of 12 and 14 can be held criminally responsible for extreme and cruel cases resulting in death or disability—but their legal prosecution must first be approved by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP).

It has not done much to stop the violence.

Discussions around extreme bullying like this have repeatedly flared up over the years, such as in 2020, when a 15-year-old schoolboy named Yuan (袁) in Shaanxi was fatally beaten and buried by a group of minors.

Last year, a young boy named Wang Ziyao (王子耀) was killed by three classmates after suffering years of bullying. His body was found in a greenhouse just 100 meters from the home of one of the suspects, and the case shocked and enraged local residents.

But the problem is widespread among girls, too.

In 2016, we already reported on how so-called ‘campus violence videos’ (校园暴力视频) had become a concerning trend. In these kinds of videos—often showing multiple bullies beating up a single victim on camera—it’s not uncommon to see girls as the aggressors.

Girls often form cliques to gang up on a victim to show that they are in control or to gain popularity. They also tend to be more inclined than boys to make cruel jokes or stage pranks meant to embarrass or humiliate their target. This may partly explain why there seem to be more campus violence videos on Chinese social media showing girls bullying girls than boys bullying boys.

In the case of Lai, she appears to have been particularly vulnerable. One of her relatives posted online that her mother is deaf and mute, and her father allegedly is disabled. This fact may have contributed to why Lai was repeatedly targeted and bullied by the same group of girls, who reportedly took away her phone and socially isolated her at school.

In response to the incident, netizens started posting the hashtag “Parents Speak Up for the Bullied Girl” (“#家长们为被霸凌女孩发声#), not only to support Lai and her family, but to demand harsher punishments for school bullies and for stricter crackdown on this nationwide problem.

From Online Anger to Offline Protest

While many people spoke out for Lai online, hundreds also wanted to show up for her in person.

On August 4, dozens of people gathered in front of the Jiangyou Municipal Government building (江油市人民政府) to demand justice and support Lai’s parents, who had come to express their grievances to the authorities—at one point even bowing to the ground in a plea for justice to be served for their daughter.

Footage and images circulating on social media showing the parents of Lai, the victim, bowing on the ground to demand justice from authorities.

As the crowd grew larger, tensions escalated, eventually leading to clashes between protesters and police.

The arrests at the scene did little to ease the situation. As night fell, the mood grew increasingly grim, and some protesters began throwing objects at the police.

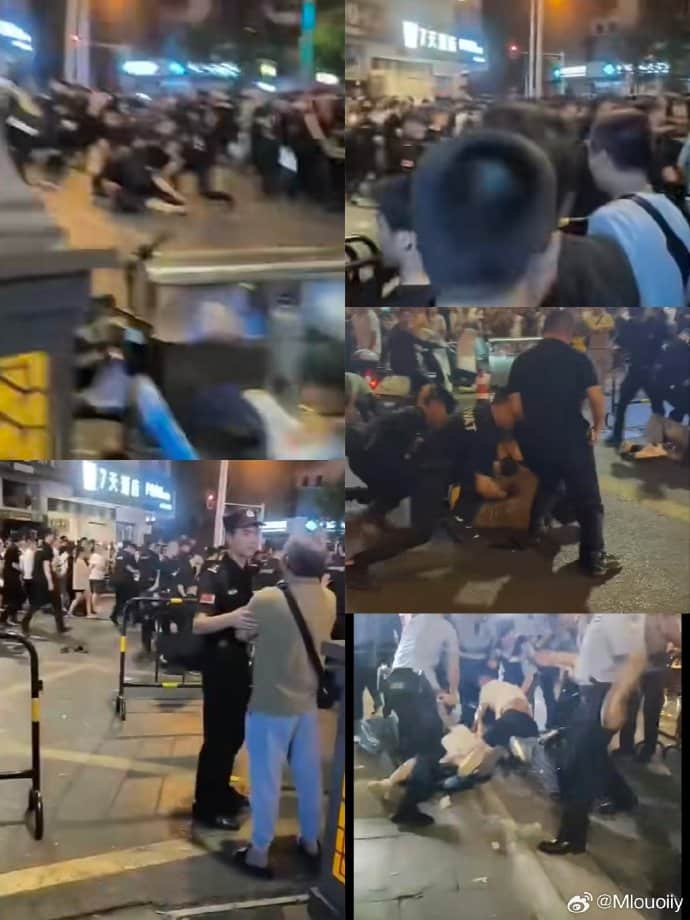

Images of the protest, posted on Weibo.

Near the east section of Shixian Road (诗仙路东段), more people gathered. Hundreds of individuals filming and livestreaming captured footage of the police crackdown—officers beating protesters, dragging them away, and deploying pepper spray.

Netizens’ digital artwork about the bullying incident, the parents’ grievances, and the public protest and its crackdown in Jiangyou. Shared by 程Clarence.

Although the protests briefly gained traction on social media and became a trending topic on Weibo, the search term was soon removed from the platform’s trending list.

Lasting Mental Scars

On Tuesday, August 5, several topics related to the Jiangyou bullying incident began trending again on Chinese social media.

On the short video app Kuaishou, a collective demand for justice surged to the number one spot, under the tag “A large number of Jiangyou parents demand justice for the victim” (江油大批家长为受害学生讨公道).

As of now, none of the perpetrators’ families have come forward to apologize.

As for Lai—according to the latest reports, she did not suffer serious physical injuries from the bullying incident, but according to her own parents, the mental scars will last. She will need continued mental health support and counseling going forward.

Although many posts about the incident and the ensuing protests have been taken offline, ‘Jiangyou’s Bullying Incident’ has already become one more case in the growing list of brutal school bullying incidents that have surfaced on Chinese social media in recent years. The heat of local anger may fade over time, but the rising number of such cases continues to fuel public frustration nationwide—especially if local authorities fail to do more to address and prevent school bullying.

“Not being able to protect our children, that’s a disgrace to our schools and the police,” one commenter wrote: “I want to thank all those mothers who have raised their voices for the bullied child. Each of us must say no to bullies, and we must do all we can to stop them. I hope the lawmakers agree.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment7 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West