China Insight

100 Terms the Communist Party Wants You to Know for the 19th National Congress

100 “must-know” terms for the 19th National Congress, propagated by People’s Daily.

Published

7 years agoon

These are the 100 terms to know for the 19th CPC National Congress – propagated by People’s Daily, the mouthpiece of China’s ruling Communist Party, on Weibo.

It is the week of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), better known as the “19th Party Congress.” This meeting, that takes place from October 18 to October 24, is a major event that takes place every five years.

On Chinese social media, Communist Party newspaper People’s Daily (@人民日报) presented a vocabulary list for people to know before the huge political event.

During the 19th Party Congress approximately 2280 delegates from across the nation officially come together to select the party’s top leadership for the next five years. The event is also called a “celebration of decisions that have already been taken,” as the key points of the meeting have mostly already been settled behind closed doors.

It is these key decisions for China that will be discussed during the CPC National Congress and then officially announced, representing “new governance concepts, thoughts and strategies proposed by the CPC Central Committee with Xi Jinping at its core” (Xinhua).

In a recent report by APCO Worldwide, Gary Li summarizes what to look out for during the 19th National Congress, writing that it is likely for President Xi Jinping to “consolidate his power further by making changes to the party apparatus,” influencing regulators in various sectors from finance to trade and cybersecurity.

Posting the 9-page list of a total of 100 terms on Weibo, People’s Daily (@人民日报) writes:

“Study time! We want to teach you the translation of 100 hot terms for the 19th CPC National Congress (..) Do you know how to say these things in English? This is how to avoid using Chinglish and to express [these terms] in a more authentic way. They are all useful for CET-4 & CET-6 [national English level tests in China] and other exams. Let’s learn these!”

By October 18, the list was shared 19000 times on Weibo and received many comments.

One netizen said: “With these 100 words you can understand a new China.” Others complained that they still think the English translation of these Chinese terms “sounds like Chinglish.”

Relevant Words: Policy Trends & Digital Focus

The vocabulary list, which was selected from China Daily‘s “Little Red Book of Hot Words” (热词红宝书), is an interesting combination of terms that says a lot about the focal points of the National Congress and the trends that are emphasized for the coming five years.

In the recent APCO report, Gary Li mentions Ideological Tightening as a crucial policy trend. This promotion of “Chinese values” is clearly visible in the vocabularly list, that includes terms such as “the Chinese Dream” (中国梦), “Stay true to the mission” (不忘初心), and “cultural confidence” (文化自信).

Another important policy trend on the government agenda is Anti-Corruption, which is represented by the term “anti-corruption TV series” (反腐剧).

The list also includes some Internet slang terms such as “give a like” (点赞) or “phubber”/”bowed head clan” (低头族), referring to people who constantly look down to their smartphone.

It also includes a catchphrase that became especially popular on Chinese social media in 2016 when it was used by Chinese swimming champion Fu Yuanhui during an interview about her winning medal during the Olympics – (“用了洪荒之力”), which can be translated as “I’ve used my primeval powers!”, basically meaning “to give one’s full play.”

Swimmer Fu Yuanhui went viral in 2016 when she introduced a new catchphrase that is still a hot online sentence.

The inclusion of some typical internet catchphrases is especially noteworthy because in 2014, Chinese state media published that programs and commercials should not use Internet language to preserve traditional expressions.

The entire list has a clear Digital Focus when it comes to different industries, including government, media, finance, and traveling, introducing words such as “in-flight Wifi services” (空中上网服务), “face scan payment” (扫脸支付), 5G era (5G时代), and taxi-hailing app (打车软件).

The Belt and Road initiative and China’s role in the world is an important point on this year’s agenda.

The list also includes words that emphasize the Belt and Road Initiative and China-centric Relations for Economy and Trade, such as the “New type of major-power relationship” (新型大国关系).

The List: 100 Hot Words for the 19th National Congress

This is the full list of the 100 terms as shared by the People’s Daily through screenshots, typed out by What’s on Weibo. The pinyin and tones are also provided by What’s on Weibo.

1. 中国梦

Zhōngguó mèng

China dream

2. 不忘初心

Bù wàng chūxīn

Stay true to the mission

3. 两个一百年

Liǎng gè yībǎi nián

Two centenary goals

4. 新常态

Xīn chángtài

New normal

5. 中国制造2025

Zhōngguó zhìzào 2025

Made in China 2025

6. “双一流”

Shuāng yīliú

Double First-Class initiative

7. 工匠精神

Gōngjiàng jīngshén

Craftsmanship spirit

8. 中国天眼:500米口径球面射电望远镜(FAST)

Zhōngguó tiānyǎn:500 Mǐ kǒujìng qiúmiàn shèdiàn wàngyuǎnjìng (FAST)

China’s Eye of Heaven: The 500-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope

9. 歼-20战斗机

Jiān-20 zhàndòujī

J-20 Stealth Fighter

10. 国产航母

Guóchǎn hángmǔ

Domestically built aircraft carrier

11. 国产客机

Guóchǎn kèjī

Homemade passenger jet

12. 可燃冰试采

Kěrán bīng shì cǎi

Sampling of combustible ice

13. 量子卫星”墨子号”

Liàngzǐ wèixīng “mò zi hào”

Quantum satellite “Micius”

14. 北斗卫星导航系统

Běidǒu wèixīng dǎoháng xìtǒng

Beidou navigation system

15. 风云四号A星卫星

Fēngyún sì hào A xīng wèixīng

Fengyun-4A satellite

16. 重型运载火箭

Zhòngxíng yùnzài huǒjiàn

Heavy-lift Carrier Rocket

17. 沪港通

Hù gǎng tōng

Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect

18. 深港通

Shēn gǎng tōng

Shenzhen-Hong Kong Stock Connect

19. 京津冀一体化

Jīng jīn jì yītǐ huà

Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei integration

20. 雄安新区

Xióng ān xīnqū

Xiong’an New Area

21. 自贸实验区

Zì mào shíyàn qū

Pilot Free Trade Zones

22. 医疗改革

Yīliáo gǎigé

Medical Reform

23. 供给侧改革

Gōngjǐ cè gǎigé

Supply-side reform

24. 扫脸支付

Sǎo liǎn zhīfù

Face scan payment

25. 二维码支付

Èr wéi mǎ zhīfù

Two-dimensional barcode payment

26. 人工智能

Réngōng zhìnéng

Artificial intelligence

27. 虚拟现实

Xūnǐ xiànshí

Virtual reality

28. 5G时代

5G shídài

5G era

29. 分享经济

Fēnxiǎng jīngjì

Sharing economy

30. 互联网金融

Hùliánwǎng jīnróng

Online finance

31. 亚投行

Yà tóuháng

Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank

32. 低碳城市

Dī tàn chéngshì

Low-carbon cities

33. 一小时通通勤圈

Yī xiǎoshí tōng tōngqín quān

One-hour commuting circle

34. 蓝色经济

Lán sè jīngjì

Blue economy

35. 纵向横向经济轴带

Zòngxiàng héngxiàng jīngjì zhóu dài

North-south and east-west intersecting economic belts

36. 众创、众包、众扶、众筹

Zhòng chuàng, zhòng bāo, zhòng fú, zhòng chóu

Crowd innovation, crowdsourcing,crowd support and crowdfunding.

37. 战略性新兴产业

Zhànlüè xìng xīnxīng chǎnyè

Emerging sectors of strategic importance

38. 香港回归祖国20周年

Xiānggǎng huíguī zǔguó 20 zhōunián

The 20th anniversary of Hong-Kong’s return to China

39. 点赞

Diǎn zàn

Give a like

40.自媒体

Zì méitǐ

We-Media

41. 实名认证

Shímíng rènzhèng

Real name authentication

42. 精准扶贫

Jīngzhǔn fúpín

Targeted poverty reduction

43. 精准医疗

Jīngzhǔn yīliáo

Precision medicine

44. 利益共同体

Lìyì gòngtóngtǐ

Community of shared interests

45. 轨道交通

Guǐdào jiāotōng

Rail traffic

46. 动车

Dòngchē

Bullet train

47. 城际列车

Chéng jì lièchē

Inter-city transport

48. “一带一路”倡议

“Yīdài yīlù”chàngyì

Belt and Road Initiative

49. “丝绸之路经济带”

“Sīchóu zhī lù jīngjì dài”

The Silk Road Economic Belt

50. 21世纪海上丝绸之路

21 Shìjì hǎishàng sīchóu zhī lù

21st- Century Maritime Silk Road

51. 古丝绸之路

Gǔ sīchóu zhī lù

The Ancient Silk Road

52. 互联互通

Hùlián hùtōng

Establish and Strengthen Partnerships/Connectivity

53. 文化自信

Wénhuà zìxìn

Cultural confidence

54. 新型大国关系

Xīnxíng dàguó guānxì

New type of major-power relationship

55. 可替代能源汽车

Kě tìdài néngyuán qìchē

Alternative energy vehicle

56. 可载人无人机

Kě zài rén wú rén jī

Passenger-carrying drone

57. 空中上网服务

Kōngzhōng shàngwǎng fúwù

In-flight Wifi services

58. 海外购外

Hǎiwài gòu wài

Overseas shopping representative

59. 海淘

Hǎi táo

Cross-border online shopping

60. 多次往返签证

Duō cì wǎngfǎn qiānzhèng

Multiple entry visa

61. 散客

Sǎn kè

Individual traveler

62. 自由行

Zìyóu xíng

Independent travel

63. 跟团游

Gēn tuán yóu

Package tour

64.深度游

Shēndù yóu

In-depth travel

65. 自驾游

Zìjià yóu

Self-driving tours

66. 免税店

Miǎnshuì diàn

Duty-free store

67. 无现金支付

Wú xiànjīn zhīfù

Cashless payment

68. 旺季

Wàngjì

Peak season

69. 淡季

Dànjì

Offseason

70. 反腐剧

Fǎnfǔ jù

Anti-corruption TV series

71. 合拍片

Hépāi piàn

Co-production

72. 打车软件

Dǎchē ruǎnjiàn

Taxi-hailing app

73. 代驾服务业

Dài jià fúwù yè

Designated driver business

74. 单双号银行

Dān shuāng hào yínháng

Traffic restrictions based on even- and odd-numbered license plates

75. 共享汽车

Gòngxiǎng qìchē

Car-sharing

76. 绿色金融改革新试验区

Lǜsè jīnróng gǎigé xīn shìyàn qū

Pilot zones for green finance reform and innovations

77. 超国民待遇

Chāo guómín dàiyù

Super-national treatment

78. 现代医院管理制度

Xiàndài yīyuàn guǎnlǐ zhìdù

Modern hospital management system

79. 机遇之城

Jīyù zhī chéng

Cities of opportunities

80.直播经济

Zhíbò jīngjì

Live stream economy

81. 互联网+政府服务

Hùliánwǎng +zhèngfǔ fúwù

Internet Plus government services

82. 创新型政府

Chuàngxīn xíng zhèngfǔ

Pro-innovation government

83. 无人机紧急救援队

Wú rén jī jǐnjí jiùyuán duì

UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) emergency rescue team

84. 二孩经济

Èr hái jīngjì

Second-child economy

85.父亲假;陪产假

Fùqīn jià; péi chǎnjià

Paternity leave

86. 带薪休假

Dài xīn xiūjià

Paid leave

87. 低头族

Dītóu zú

Phubber

88. 副中心

Fù zhōngxīn

Subcenter

89. 用了洪荒之力

Yòngle hónghuāng zhī lì

Give one’s full play

90. 营改增

Yíng gǎi zēng

Replace business tax with value-add tax (VAT)

91. 创新型人才

Chuàngxīn xíng réncái

Innovative talent

92. 积分落户制度

Jīfēn luòhù zhìdù

Points-based hukou system

93. 混合所有制改革

Hùnhé suǒyǒuzhì gǎigé

Mixed-ownership reform

94. 税收减免

Shuìshōu jiǎnmiǎn

Tax reduction and exemption

95. 生态保护红线

Shēngtài bǎohù hóngxiàn

Ecological wealth

96. 网约车

Wǎng yuē chē

Online car-hailing

97. 宜居城市

Yí jū chéngshì

Habitable city

98. 移动支付

Yídòng zhīfù

Mobile payment

99. 电子竞技

Diànzǐ jìngjì

E-sports

100. 双创人才

Shuāng chuàng réncái

Innovative and entrepreneutrial talent

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Insight

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

The story of ‘Fat Cat’ has become a hot topic in China, sparking widespread sympathy and discussions online.

Published

3 months agoon

May 9, 2024

The tragic story behind the recent suicide of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ has become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media, touching upon broader societal issues from unfair gender dynamics to businesses taking advantage of grieving internet users.

The story of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer from Hunan who committed suicide has gone completely viral on Weibo and beyond this week, generating many discussions.

In late April of this year, the young man nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ (胖猫 Pàng Māo, literally fat or chubby cat), tragically ended his life by jumping into the river near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge (重庆长江大桥) following a breakup with his girlfriend. By now, the incident has come to be known as the “Fat Cat Jumping Into the River Incident” (胖猫跳江事件).

News of his suicide soon made its rounds on the internet, and some bloggers started looking into what was behind the story. The man’s sister also spoke out through online channels, and numerous chat records between the young man and his girlfriend emerged online.

One aspect of his story that gained traction in early May is the revelation that the man had invested all his resources into the relationship. Allegedly, he made significant financial sacrifices, giving his girlfriend over 510,000 RMB (approximately 71,000 USD) throughout their relationship, in a time frame of two years.

When his girlfriend ended the relationship, despite all of his efforts, he was devastated and took his own life.

The story was picked up by various Chinese media outlets, and prominent social and political commentator Hu Xijin also wrote a post about Fat Cat, stating the sad story had made him tear up.

As the news spread, it sparked a multitude of hashtags on Weibo, with thousands of netizens pouring out their thoughts and emotions in response to the story.

Playing Games for Love

The main part of this story that is triggering online discussions is how ‘Fat Cat,’ a young man who possessed virtually nothing, managed to provide his girlfriend, who was six years older, with such a significant amount of money – and why he was willing to sacrifice so much in order to do so.

The young man reportedly was able to make money by playing video games, specifically by being a so-called ‘booster’ by playing with others and helping them get to a higher level in multiplayer online battle games.

According to his sister, he started working as a ‘professional’ video gamer as a means of generating money to satisfy his girlfriend, who allegedly always demanded more.

He registered a total of 36 accounts to receive orders to play online games, making 20 yuan per game (about $2.80). Because this consumed all of his time, he barely went out anymore and his social life was dead.

In order to save more money, he tried to keep his own expenses as low as possible, and would only get takeout food for himself for no more than 10 yuan ($1,4). His online avatar was an image of a cat saying “I don’t want to eat vegetables, I want to eat McDonald’s.”

The woman in question who he made so many sacrifices for is named Tan Zhu (谭竹), and she soon became the topic of public scrutiny. In one screenshot of a chat conversation between Tan and her boyfriend that leaked online, she claimed she needed money for various things. The two had agreed to get married later in this year.

Despite of this, she still broke up with him, driving him to jump off the bridge after transferring his remaining 66,000 RMB (9135 USD) to Tan Zhu.

As the story fermented online, Tan Zhu also shared her side of the story. She claimed that she had met ‘Fat Cat’ over two years ago through online gaming and had started a long distance relationship with him. They had actually only met up twice before he moved to Chongqing. She emphasized that financial gain was never a motivating factor in their relationship.

Tan additionally asserted that she had previously repaid 130,000 RMB (18,000 USD) to him and that they had reached a settlement agreement shortly before his tragic death.

Ordering Take-Out to Mourn Fat Cat

– “I hope you rest in peace.”

– “Little fat cat, I hope you’ll be less foolish in your next life.”

– “In your next life, love yourself first.”

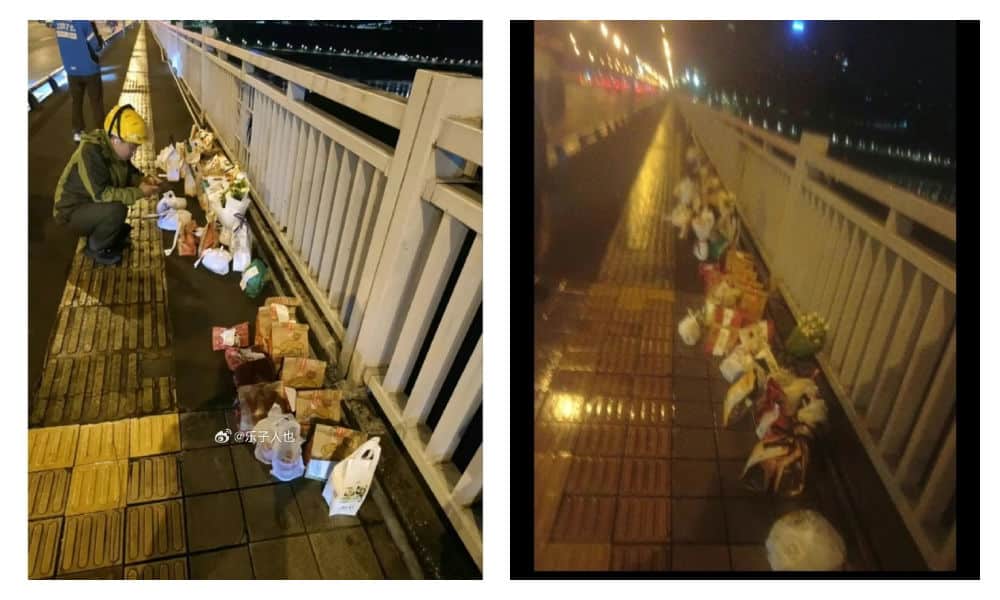

These are just a few of the messages left by netizens on notes attached to takeout food deliveries near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge.

AI-generated image spread on Chinese social media in connection to the event.

As Fat Cat’s story stirred up significant online discussion, with many expressing sympathy for the young man who rarely indulged in spending on food and drinks, some internet users took the step of ordering McDonalds and other food delivery services to the bridge, where he tragically jumped from, in his honor.

This soon snowballed into more people ordering food and drinks to the bridge, resulting in a constant flow of delivery staff and a pile-up of take-out bags.

Delivery food on the bridge, photo via Weibo.

However, as the food delivery efforts picked up pace, it came to light that some of the deliveries ordered and paid for were either empty or contained something different; certain restaurants, aware of the collective effort to honor the young man, deliberately left the food boxes empty or substituted sodas or tea with tap water.

At least five restaurants were caught not delivering the actual orders. Chinese bubble tea shop ChaPanda was exposed for substituting water for milk tea in their cups. On May 3rd, ChaPanda responded that they had fired the responsible employee.

Another store, the Zhu Xiaoxiao Luosifen (朱小小螺蛳粉), responded on that they had temporarily closed the shop in question to deal with the issue. Chinese fast food chain NewYobo (牛约堡) also acknowledged that at least twenty orders they received were incomplete.

Fast food company Wallace (华莱士) responded to the controversy by stating they had dismissed the employees involved. Mixue Ice Cream & Tea (蜜雪冰城) issued an apology and temporarily closed one of their stores implicated in delivering empty orders.

In the midst of all the controversy, Fat Cat’s sister asked internet users to refrain from ordering take-out food as a means of mourning and honoring her brother.

Nevertheless, take-out food and flowers continued to accumulate near the bridge, prompting local authorities to think of ways of how to deal with this unique method of honoring the deceased gamer.

Gamer Boy Meets Girl

On Chinese social media, this story has also become a topic of debate in the context of gender dynamics and social inequality.

There are some male bloggers who are angry with Tan Zhu, suggesting her behaviour is an example of everything that’s supposedly “wrong” with Chinese women in this day and age.

Others place blame on Fat Cat for believing that he could buy love and maintain a relationship through financial means. This irked some feminist bloggers, who see it as a chauvinistic attitude towards women.

A main, recurring idea in these discussions is that young Chinese men such as Fat Cat, who are at the low end of the social ladder, are actually particularly vulnerable in a fiercely competitive society. Here, a gender imbalance and surplus of unmarried men make it easier for women to potentially exploit those desperate for companionship.

The story of Fat Cat brings back memories of ‘Mo Cha Official,’ a not-so-famous blogger who gained posthumous fame in 2021 when details of his unhappy life surfaced online.

Likewise, the tragic tale of WePhone founder Su Xiangmao (苏享茂) resurfaces. In 2017, the 37-year-old IT entrepreneur from Beijing took his own life, leaving behind a note alleging blackmail by his 29-year-old ex-wife, who demanded 10 million RMB (±1.5 million USD) (read story).

Another aspect of this viral story that is mentioned by netizens is how it gained so much attention during the Chinese May holidays, coinciding with the tragic news of the southern China highway collapse in Guangdong. That major incident resulted in the deaths of at least 48 people, and triggered questions over road safety and flawed construction designs. Some speculate that the prominence given to the Fat Cat story on trending topic lists may have been a deliberate attempt to divert attention away from this incident.

‘Fat Cat’ was cremated. His family stated their intention to take necessary legal steps to recover the money from his former girlfriend, but Tan Zhu reportedly already reached an agreement with the father and settled the case. Nevertheless, the case continues to generate discussions online, with some people wondering: “Is it over yet? Can we talk about something different now?”

Fat Cat images projected in Times Square

However, given that images of the ‘Fat Cat’ avatar have even appeared in Times Square in New York by now (Chinese internet users projected it on one of the big LED screens), it’s likely that this story will be remembered and talked about for some time to come.

UPDATE MAY 25

On May 20, local authorities issued a lengthy report to clarify the timeline of events and details surrounding the death of “Fat Cat,” which had attracted significant attention across China.

The report concluded that there was no fraud involved and that “Fat Cat” and his girlfriend were in a genuine relationship. Tan did not deceive “Fat Cat” for money; the transfers were voluntary. Furthermore, Tan returned most of the money to his parents.

The gamer’s sister is reportedly still being investigated for potentially infringing on Tan’s privacy by disclosing numerous private details to the public.

In the end, one thing is clear in this gamer’s tragic story, which is that there are no winners.

By Manya Koetse

– With contributions by Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

3 months agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

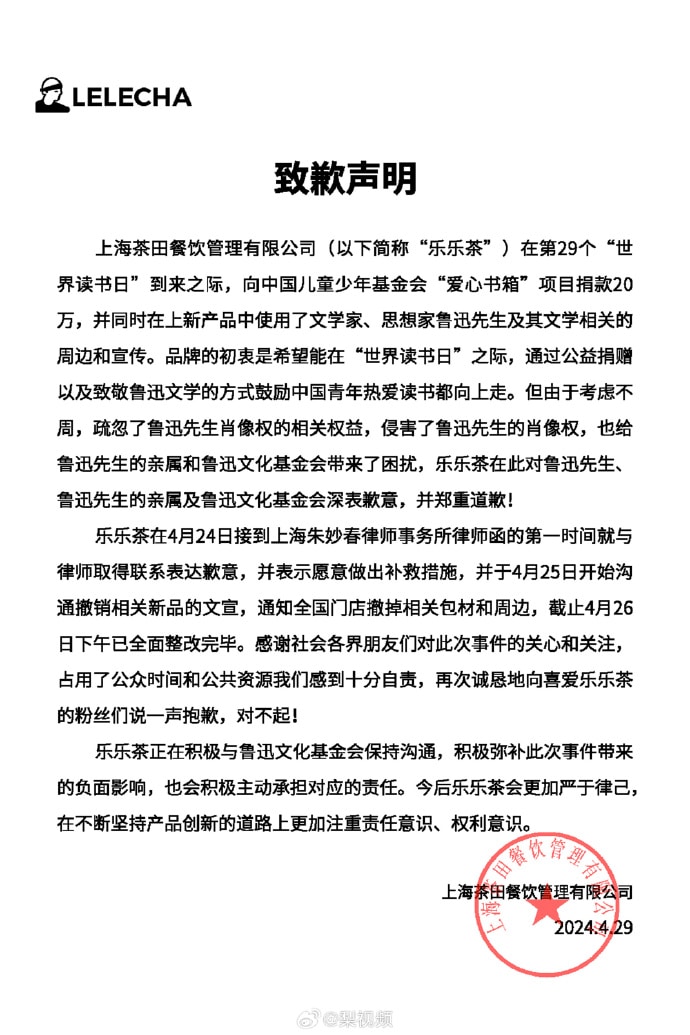

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

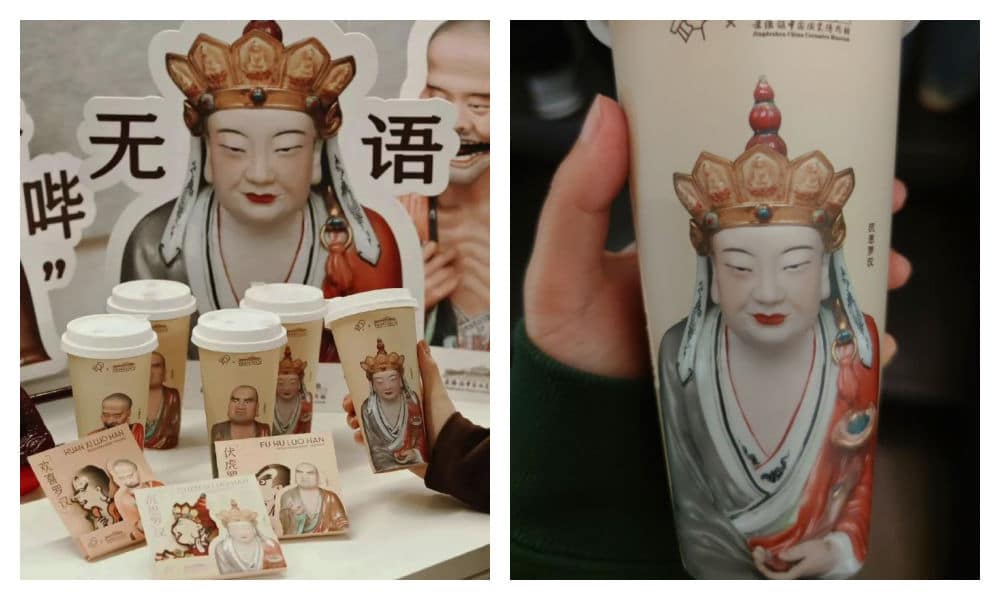

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?