China Media

Chinese Media Coverage of China’s Rescue Efforts in Turkey-Syria Earthquake

Chinese state media have framed China’s rescue efforts in Turkey and Syria as being in line with the responsibilities of a great nation.

Published

3 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

After the devastating earthquake that hit southern Turkey and northern Syria on February 6, killing over 25,000 36,000 people, rescue teams from all over the world have come to provide assistance in the quake-hit areas and dozens of countries have reached out to help in various ways.

On Chinese social media, China’s efforts to assist Turkey and Syria have become big topics in ongoing discussions about the earthquake.

Topics such as China sending cash aid to the disaster areas, along with rice and wheat and tents, blankets, etc., have been widely covered by online media this week (#中国220吨小麦将运抵叙利亚#), but it is the efforts of the Chinese rescue teams that have received the most attention when it comes to China’s assistance to the quake-hit areas.

State media outlets mostly drive the online attention for the Chinese rescue groups in Turkey and Syria. People’s Daily, Xinhua, China News Service, and CCTV all report about the rescue efforts of the teams from China.

Chinese Rescue Teams in Turkey and Syria

Several rescue teams from China have come to the quake-hit areas. Apart from the official China Search and Rescue Team, there are also Chinese civilian rescue teams, including the Blue Sky Rescue Team and Ram Rescue Team. The Red Cross Society of China (RCSC) also sent a rescue team to Syria on Thursday.

The official Chinese Rescue team – the China International Search and Rescue Team (CISAR/中国国际救援队)- consists of experienced members from, among others, the Beijing fire and rescue corps, the National Earthquake Response Support Service, and some of them are emergency hospital staff. They also brought four rescue dogs with them.

A first batch consisting of 82 rescuers dispatched by the Chinese government arrived at the disaster area on Wednesday (#中国救援队82人抵达土耳其#).

The Blue Sky Rescue Team (蓝天救援队) is a professional non-profit search-and-rescue organization with more than 30,000 registered volunteers. Founded in 2007, it is China’s largest nonprofit civil rescue organization.

China’s Blue Sky Rescue Teams arrived in Turkey on February 8 and 9, including the local Chongqing, Hainan, Fujian, Jiangsu, and Hunan teams. They also brought special earthquake rescue and alarm systems with them.

The ‘Ram Rescue Team’ or ‘Rescue Team of Ramunion’ (公羊救援队) is a professional volunteer team specializing in outdoor emergency rescue tasks. The team, founded in 2008, has participated in various rescue efforts. They previously also provided assistance during earthquake rescue situations in Nepal, Pakistan, Ecuador, Italy, and Indonesia on behalf of China’s civilian rescue forces.

Nine members of the Zhejiang Ram Rescue Team arrived in Turkey’s Adana on Wednesday, bringing a rescue dog. Seven more members arrived from Sichuan on Friday.

Rescue-Related Hashtags on Social Media

#蓝天救援队在机场遇到感人一幕# – Chinese state media outlet Xinhua News reported that some members of the Blue Sky Team ran into local people upon their arrival in Turkey, who were moved to see the teams coming in from China.

#公羊救援队救出1男子和1儿童# – At about 9 am local time on Feb. 9 in Turkey, China’s Ram Rescue Team rescued a man and a child.

#中国救援队救出第二名幸存者# – On Feb. 9, Chinese state media reported that a Chinese rescue team and a local rescue team managed to rescue a survivor in Turkey. The person, a pregnant woman, was taken to the hospital by ambulance for treatment.

#公羊救援队与土方合力救出一家5口# – The same day at 1:30 pm local time, the Chinese Ram Rescue Team, together with the Turkish Army urban search team, successfully rescued a family consisting of 2 adults and 3 children in Belen Town.

#公羊救援队成功救援一户家庭# – On Feb 9., Chinese state media outlet People’s Daily reported that the Chinese rescue workers joined forces with local rescue teams in rescuing a family of two adults and three children from the earthquake rubble on Thursday afternoon.

#中国救援队成功营救出第3名幸存者# – At 8pm local time on February 9, a Chinese rescue team and the local Turkish rescue force managed to rescue a female survivor from a collapsed 7-story building. At this time, over 80 hours had already passed since the earthquake.

#中国救援队连夜奋战拯救生命# – Xinhua News reported that Chinese teams continued to work throughout the night in order to try and rescue more people.

#中国救援队救出被埋100小时幸存者# – CCTV reported on Friday that, through the joint efforts of Chinese and Turkish rescue teams, a woman who was trapped inside a collapsed building was able to be rescued from the ruins after 100 hours.

#搜救犬Lucky上岗首日寻获1名幸存者# – On Feb 10. China’s Ram Rescue Team and the search and rescue dog Lucky provided assistance to Turkish rescue workers in rescuing one survivor.

#中国救援队成功救出第四人# – Around 3:40 pm on Friday, the Chinese rescue team managed to rescue another earthquake survivor trapped inside a collapsed building in Antakya.

#蓝天救援队第二梯队赴土救灾# – A second Blue Sky Team headed to Turkey on Saturday, Feb 11, to help disaster victims. Besides equipment, the team brings all kinds of food to the disaster area, including instant noodles, pickled mustard, and Laoganma.

#蓝天救援队有人借钱去土耳其# – China News Service reported that some members of China’s Blue Sky Rescue team had to borrow money to get to Turkey. Rescue members of the civilian rescue team pay for travel costs themselves, spending over 20,000 yuan ($2937) per member.

#官方呼吁尚未启程救援队取消行动# – On Saturday, Feb. 11, China’s Association for Disaster Prevention called on Chinese civilian rescue teams that had not yet left China to cancel or suspend their plans to go to the disaster area. As the rescue work had reached its fifth day, survival chances have greatly dropped and in order to let emergency relief aid workers do their work and not to add burden, the official advice is to suspend traveling to Turkey at this time.

‘Major Power’ Humanitarian Aid

Chinese state media have also framed China’s rescue efforts in Turkey and Syria as being in line with the responsibilities of a great nation (“大国风范,” “大国的担当,” “大国担当”), as providing international humanitarian assistance is generally seen as being part of the role of a major power.

Chinese media outlet Rednet reported how the speed and efficiency in which the Chinese government organized rescue teams to send to Turkey and Syria demonstrate China’s power to the rest of the world as a “Chinese miracle” (“中国奇迹”).

In recent years, China’s role in international rescue operations has become increasingly important. The experiences and lessons of China’s rescue teams during the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan have also contributed to the development of China’s disaster emergency rescue system in various ways, including inter-organizational coordination (Lin et al 2-17).

This week, China Daily provided an overview of some of the rescue efforts China has contributed to in recent years, including the 2019 Mozambique cyclone disaster, the 2015 Nepal earthquake, the 2011 Japan tsunami, the 2010 Haiti Earthquake, and the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake.

On Weibo, the China Communist Youth League also initiated the hashtag “In 20 Years, China Has Participated in 12 International Rescue Operations” (#20年来中国共参与过12次国际救援#).

“Our motherland is powerful, they are taking responsibility,” one Weibo commenter wrote: “No matter if it is official teams or civilian ones, they embody the air of a great power. It’s moving.”

By Manya Koetse

References

Lin, Xi, Ke-Jia Liu, Yong-Gui Zhang, Yang Dan, Dian-Guo Xing, Li Chen, Ding-Yuan Du. 2017. “China Medical Team: Medical rescue for “4.25” Nepal Earthquake.” Chinese Journal of Traumatology 20 (2017) 235-239.

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Digital

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

A virtual Viagra for a pressured generation? The real story behind China’s latest viral app.

Published

2 weeks agoon

January 14, 2026

From censored joke to state-friendly app, ‘Are You Dead Yet?’ has traveled a long road before reaching the top of China’s paid app charts this week. While marketed as a tool for those living alone to check in with emergency contacts, the app’s viral success actually isn’t all about its features.

It is undoubtedly the most unexpected app to go viral in 2026, and the year has only just started. “Are You Dead?” or “Dead Yet?” (死了么, Sǐleme) is the name of the daily check-in app that surged to the No. 1 spot on Apple’s paid app chart in China on January 10–11, quickly becoming a widely discussed topic on Chinese social media. It has since become a top-searched topic on the Q&A platform Zhihu and beyond, and by now, you may even have noticed it appearing on your local news website.

For many Chinese who first encountered the app, its name caused unease. In China, casually invoking words associated with death is generally considered taboo, seen as causing bad luck. It was therefore especially noteworthy to see state media outlets covering the trend. The fact that the name plays on China’s popular food delivery platform Ele.me (饿了么, “Hungry Yet?”), a household name, may also have softened the linguistic sensitivity.

Beyond the name, attention soon shifted to the broader social undercurrents and collective anxieties reflected in the app’s sudden popularity.

🔹 “A More Reassuring Solo Living Experience”

Are You Dead Yet? is a basic app designed as a safety tool for people living alone, allowing them to “check in” with loved ones. The Chinese app has been available on Apple’s App Store since 2025 and currently costs 8 yuan (US$1.15) to download.

The app is very straightforward and does not require registration or login. Users simply enter their name and an emergency contact’s email address. Each day, they tap a button to virtually “check in.”

If a user fails to check in for two consecutive days, the system automatically sends an email notification to the designated emergency contact the following day, prompting them to check on the user’s safety.

The app was created by Guo Mengchu (郭孟初) and two of his Gen Z friends from Zhengzhou, all born after 1995. Together, they founded the company Moonlight Technology (月境技术服务有限公司) in March 2025, with a registered capital of 100,000 yuan (US$14,300). The app was reportedly developed in just a few weeks at a cost of approximately 1,000 yuan (around US$143).

In the text introducing the Dead Yet? app, the makers write that the app is specifically intended to “build seamless security protection for a more reassuring solo living experience” (“构建无感化安全防护,让独处生活更安心”).

🔹 The Rise of China’s Solo-Living Households

The number of solo households in China has skyrocketed over the past three decades. In the mid-1990s, only 5.9% of households in China were one-person households. By 2011, that number had nearly tripled from 19 million to 59 million, accounting for nearly 15% of China’s households.1,2 By now, the number is bigger than ever: single-person households account for over 25% of all family households.3

These roughly 125 million single-person households are partly the result of China’s rapidly aging society, along with its one-child policy. With longer life expectancies and record-low birth rates, more elderly people, especially widowed women, are living alone without their (grand)children.

China’s massive urban-rural migration, along with housing reforms that have adapted to solo-living preferences, has also contributed to the fact that China is now seeing more one-person households than ever before. By 2030, the number may exceed 150 million.

But other demographic shifts play an increasingly important role: Chinese adults are postponing marriage or not getting married at all, while divorce rates are rising. Over the past few years, Chinese authorities have introduced various measures to encourage marriage and childbirth, from relaxed registration rules to offering benefits, yet a definitive solution to combat China’s declining birth rates remains elusive.

🔹 A “Lonely Death”: Kodokushi in China

Especially for China’s post-90s generation, remaining unmarried and childless is often a personal choice. On apps like Xiaohongshu, you’ll find hundreds of posts about single lifestyles, embracing solitude (享受孤独感), and “anti-marriage ideology” (不婚主义). (A few years back, feminist online movements promoting such lifestyles actually saw a major crackdown.)

Although there are clear advantages to solo living—for both younger people and the elderly—there are also definite downsides. Chinese adults who live alone are more likely to feel lonely and less satisfied with their lives 4, especially in a social context that strongly prioritizes family.

Closely tied to this loneliness are concerns about dying alone.

In Japan, where this issue has drawn attention since the 1990s, there is a term for it: kodokushi (孤独死), pronounced in Chinese as gūdúsǐ. Over the years, several cases of people dying alone in their apartments have triggered broader social anxiety around this idea of a “lonely death.”

One case that received major attention in 2024 involved a 33-year-old woman from a small village in Ningxia who died alone in her studio apartment in Xianyang. She had been studying for civil service exams and relied on family support for rent and food. Her body was not discovered for a long time, and by the time it was found, it had decomposed to the point of being unrecognizable.

Another case occurred in Shanghai in 2025. When a 46-year-old woman who lived alone passed away, the neighborhood committee was unable to locate any heirs or anyone to handle her posthumous affairs. The story prompted media coverage on how such situations are dealt with, but it drew particular attention because cases like this had previously been rare, stirring a sense of broader social unease.

🔹 The Sensitive Origins of “Dead Yet?”

Knowing all this, is there actually a practical need for an app like Dead Yet? in China? Not really.

China has a thriving online environment, and its most popular social media apps are used daily by people of all ages and backgrounds, across urban and rural areas alike. There are already countless ways to stay in touch. WeChat alone has 1.37 billion monthly active users. In theory (even for seniors) sending a simple thumbs-up emoji to an emergency contact would be just as easy as clocking in to the Dead Yet? app.

The app’s viral success, then, is not really about its functionality. Nor is it primarily about elderly people fearing a lonesome death. Instead, it speaks to the dark humor of younger adults who feel overwhelmed by pressure, social anxiety, and a pervasive sense of being unseen—so much so that they half-jokingly wonder whether anyone would even notice if they collapsed amid demanding work cultures and family expectations.

And this idea is not new.

After some online digging, I found that the app’s name had already gone viral more than two years earlier.

That earlier viral moment began with a Zhihu post titled “If you don’t get married and don’t have children, what happens if you die at home in old age?” (“不结婚不生孩子,老后死在家中怎么办”). Among the 1,595 replies, the top commenter, Xue Wen Feng Luo (雪吻枫落), whose response received 8,007 likes, wrote:

💬 “You could develop an app called “Dead Yet?” (死了么). One click to have someone come collect the body and handle the funeral arrangements.”

The original post that started it all. That humorous comment was the initial play on words linked to food delivery app Eleme (饿了么).

Two days later, on October 8, 2023, comedy creator Li Songyu (李松宇, @摆货小天才), also part of the post-90s generation, released a video responding to the comment.

In it, he presented a mock version of the app on his phone: its logo a small ghost vaguely resembling the Ele.me icon, and its interface showing some similarities to ride-hailing apps like Uber or Didi.

In the video, Li says:

🗯️ “Are You Dead Yet?’ I’ve already designed the app for you. (…) The app is linked to your smart bracelet. Once it fails to detect the user’s pulse, someone will immediately come to collect the body. Humanized service. You can choose your preferred helper for your final crossing, personalize the background music for cremation and burial, and even set the furnace temperature so you can enter the oven with peace of mind. Big-data matching is used to connect people who might have known each other in life, followed by AI-assisted cemetery matching for the afterlife traffic ecosystem—you’ll never feel alone again. After burial, all content on your phone is automatically formatted to protect user privacy and eliminate worries about what comes after. There’s a seven-day no-reason refund, almost zero negative reviews, and even an ‘Afterlife Package’ with installment payments. Invite friends to visit the grave and have them help repay the debt. And if not everything turns to ashes properly, or if you’re dissatisfied with the shape of the remains, you can invite friends to burn them again and get the second headstone at half price! How about that? Tempted?”

The original “Sileme” or “Dead Yet” app idea, October 2023.

The video went viral, drew media coverage (one report called the concept and design of the “Are You Dead?” app “unprecedented”), and sparked widespread discussion. Although viewers clearly understood that the idea—one click and someone arrives to collect the body and arrange the funeral—was a joke, it nevertheless struck a chord.

Many saw the video as a glimpse into China’s future, arguing that with extremely low birth rates and a rapidly aging society, such business ideas might one day become feasible. Some people pointed to Japan’s growing problem of elderly people dying alone, suggesting that China may come to face similar challenges. At the same time, it also sparked concerns about increasing social isolation.

Despite its popularity, both the video and the trending hashtag “Dead Yet App” (#死了么APP#) were taken offline. A comedy podcast episode discussing the concept—“Did Someone Really Create the ‘Dead Yet’ App?” (真的有人做出了“死了么”APP?), released on October 10, 2023 by host Liuliu (主播六六)—was also removed.

According to Li Songyu himself, the video went offline within 48 hours “for reasons beyond one’s control” (“出于不可抗因素”), a phrase often used to avoid explicitly referring to top-down decisions or censorship.

It is not hard to guess why the darkly humorous Dead Yet? concept disappeared. And it wasn’t only because of crude jokes or the sensitivities surrounding death.

The video appeared less than a year after the end of China’s stringent zero-Covid policies, which had been preceded by protests. In both early and late 2023, Covid infections were widespread and hospitals were overcrowded. It was therefore a particularly sensitive moment to joke about bodies, afterlife logistics, and people being “taken away.”

Moreover, 2023 was a year in which state media strongly emphasized “positive energy,” promoting stories of heroism, self-sacrifice, and resilience in the face of hardship. It was not a time to dwell on death, and certainly not through humor.

🔹 Why a Censored Idea Became a ‘State-Friendly’ App

In 2025, things looked very different. Just weeks after the current Dead Yet? app was developed, it was released on the App Store on June 10, 2025. Not only was its name identical to the app “introduced” by Li in 2023, but its logo was also a clear lookalike.

The 2023 logo and 2025 “Dead Yet?” logo’s.

Although Li Songyu published a video this week explaining that he and his team were the original creators of the Dead Yet? concept and that they had planned to develop a real app before the idea was censored (without ever registering the trademark), app creator Guo Mengchu has simply stated that the inspiration for their app came “from the internet.”

In the same interview, Guo also emphasized that the app’s sudden rise was entirely organic, with the whole process of “going viral,” from ordinary users to content creators to mainstream media, taking about a day and a half.5

However, the app’s actual track record suggests a much bumpier journey.6 Since its launch, it has been taken down once and was reportedly removed from the App Store rankings three times. Such removals commonly occur due to suspected artificial download inflation, ranking manipulation, or other compliance-related issues.

After the most recent delisting on December 15, 2025, the app returned to the App Store on December 25—and only then did it finally have its breakthrough moment.

📌 Looking at how online discussions unfolded around the app, it becomes clear that, just as in 2023, the idea of relying on technology to ensure someone will notice if you die strongly resonates with people. Many users also seem to have downloaded it simply as a quirky app to try out. Once curiosity set in, the snowball quickly started rolling.

📌 But Chinese state media have also played a significant role in amplifying the story. Outlets ranging from Xinhua (新华) and China Daily (中国日报) to Global Times (环球时报) have all reported on the app’s rise and subsequent developments.

🔎 Why was Li Songyu’s Dead Yet? app idea not allowed to remain online, while Guo’s version has been able to thrive? The difference lies not only in timing, but also in tone. Li’s original concept leaned more clearly toward implicit social critique & satire. Guo’s app, by contrast, has been framed — and received — with far less overt sarcasm. While many netizens may still interpret it as dark humor, within official narratives it aligns more neatly with the family-focused social discourse, and perhaps even functions as an implicit warning: if you end up alone, you may literally need an app to ensure you do not die unnoticed.

In this way, the young creators of the new app are, perhaps inadvertently, contributing to an ongoing official effort in media discourse and local initiatives to encourage Chinese single adults to settle down and start a family. For them, however, it is a business opportunity: more than sixty investors have already expressed interest in the app.

Funnily enough, many single men and women actually hope to use the app to support their lifestyle. When, during the upcoming Chinese New Year, parents start nagging about when they will settle down, and warn that they might otherwise die alone, they can now reply that they’ve already got an app for that.

🔹 What’s in a Name?

Over the past few days, much of the discussion has centered on the app’s name, which is what drew attention to it in the first place. As interest in the app surged, fueled by international media coverage, criticism of the name also grew. Some found it too blunt, while public commentators such as Hu Xijin openly suggested that it be changed.

Considering that the mention of death itself carries online sensitivities in China, it’s possible that there’s been some criticism from internet regulators, and the Ele.me platform also might not be too pleased with the name’s resemblance.

Whatever the exact reasons, the app’s creators announced on January 13 that they would abandon the original name and rebrand the app as its international name ‘Demumu’ (De derived from death, the rest intentionally sounds like ‘Labubu’).

This marked a notable shift in stance: just two days earlier, one of the app’s creators had stated that they had not received any formal requests from authorities to change the name and had shown no apparent intention of doing so.

Most commenters felt that without the original name, the app doesn’t make sense. “As young people, we don’t care so much about taboo words,” one commenter wrote: “Without this name, the app’s hype will be over.”

On January 14, the creators then made another U-turn and invited app users to think of a new name themselves, rewarding the first user who proposes the chosen name with a 666 yuan reward ($95).

The naming hurdles suggest the makers are quite overwhelmed by all the attention. At the same time, dozens of competing apps have already appeared. One of them, launched just a day after Are You Dead Yet? went viral, is “Are You Still Alive?” (活了么), which offers similar basic functions but is free.

This new wave of similar apps has also led more people to wonder how effective these tools really are once the quirkiness wears off. One Weibo blogger wrote:

💬 “I really don’t understand why this app went viral. You can only check in daily, and you need to miss two consecutive check-in days for the emergency contact to be alerted. That means, if something actually happens, someone will only come after three days!! You’ll be rotting away in your home!!”

Others also suggested that it is clear the app was designed by younger people—the elderly users who might need it most would likely forget to check in on a daily basis.

🔹 Why “Dead Yet?” Is Like Viagra for a Pressured Generation

Amid the flood of Chinese media coverage, one commentary by the Chinese media platform Yicai7 stands out for pinpointing what truly lies behind the app’s popularity.

The author of the piece “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Dead Yet’ App” (in Chinese) argues that the app did not win users over because of its practical utility. Its main users are young people for whom premature death is an extremely low-probability event. They are clearly not downloading the app because they genuinely fear that “no one would know if they died,” nor are they likely to check in daily for such a tiny risk.

Since the app is clearly being embraced by users that do not belong to the actual target group, it must be providing some unexpected value.

💊 The author compares this unplanned function of the app to how Viagra was originally developed to treat heart disease. In this case, app users say that interacting with Dead Yet? feels like a lighthearted joke shared between close friends, offering a sense of social empathy and emotional release in a way that does not feel pressured.

Because the pressure—that’s the problem. Yicai describes just how multidimensional the pressures facing many young adults in China today can be: there is the economic challenge of the never-ending rat race dubbed “involution” along with uncertainty in the job market; there’s the “996” extreme work culture across various industries, leaving little room for private life; traditional family expectations that clash with housing and childcare costs that many find unattainable; and the world of WeChat and other social media, which can further intensify peer pressure and anxiety.

Of course, a lot has been written about these issues through the years. But do people really get it?

According to Yicai, there’s not enough understanding or support for the kinds of challenges young people face in China today. Even worse, older generations’ own past experiences often impose additional burdens on younger people, who keep running up against traditional notions while receiving inadequate support in areas such as education, employment, housing, marriage, family life, and even healthcare.

The author describes the unexpected viral success of Dead Yet? as a mirror with a message:

💬 “The viral popularity of ‘Are You Dead?’ seems like a darkly humorous social metaphor, reminding us to pay attention to the living conditions and inner worlds of today’s youth. For the young people downloading the app, what they need clearly isn’t a functional safety application, it’s a signal that what they really need is to be seen and to be understood—a warm embrace from society.”

Will the Dead Yet? app survive its name change? Is there a future for Demumu, or whatever it will end up being called? As it is now—the basic app with check-in and email or SMS functions—it might not keep thriving beyond the hype. If it doesn’t, it has at least already fulfilled an important function: showing us that in a highly digitalized, stressful, and often isolating society where AI and social media play an increasingly major role, many people yearn for the simple reassurance of being noticed, mixed with a shared delight in dark humor. Just a little light to shine on us, to remind us that we’re not dead yet.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Thanks to Ruixin Zhang & Miranda Barnes for additional research

1 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2013. “Living Alone in China: Historical Trends, Spatial Distribution, and Determinants.”

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Living-Alone-in-China-%3A-Historical-trend-%2C-Spatial-Yeung-Cheung/8df22ddeb54258d893ad4702124066b241bbdf8d.

2 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2015. “Temporal-Spatial Patterns of One-Person Households in China, 1982–2005.” Demographic Research 32: 1103–1134.

3 Li Jinlei (李金磊). 2022. “China’s One-Person Households Exceed 125 Million: Why Are More People Living Alone?”[中国新观察|中国一人户数量超1.25亿!独居者为何越来越多?]. China News Service (中国新闻网), January 14, 2022. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cj/2022/01-14/9652147.shtml (accessed January 13, 2026).

4 Danan Gu, Qiushi Feng, and Wei-Jun Jean Yeung. 2019. “Reciprocal Dynamics of Solo Living and Health Among Older Adults in Contemporary China.”

The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 74 (8): 1441–1452. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby140.

5 Wang Fang (王方). 2026. “‘How We Went Viral: The Founder of the ‘Dead Yet?’ App Speaks Out’” [‘死了么’创始人亲述:我们是如何爆红的]. Pencil Way (铅笔道), interview with Guo (郭先生), published via 36Kr (36氪), January 13, 2026. https://www.36kr.com/p/3637294130922754 (accessed January 13, 2026).

6 Lü Qian (吕倩). 2026. “‘Am I Dead?’ App Price Raised from 1 Yuan to 8 Yuan, Previously Removed from Apple App Store Rankings Multiple Times”

[‘死了么从一元涨至八元,曾被苹果AppStore多次清榜’]. Diyi Caijing (第一财经), January 11, 2026. https://www.yicai.com/news/102997938.html (accessed January 14, 2026).

7 First Financial/Yicai (第一财经). 2026. “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Am I Dead?’ App: Young People Need a Hug” [‘死了么爆火背后,年轻人需要一个拥抱’]. Official account article, January 12, 2026. https://www.toutiao.com/article/7594671238464569899/ (accessed January 14, 2026).

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Media

China’s “AFP Filter” Meme: How Netizens Turned a Western Media Lens into Online Patriotism

Chinese netizens embraced a supposed “demonizing” Western gaze in AFP photos and made it their own.

Published

5 months agoon

September 10, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For a long time, Chinese netizens have criticized how photography of Chinese news events by Western outlets—from BBC and CNN to AFP—makes China look more gloomy or intimidating. During this year’s military parade, the so-called “AFP filter” once again became a hot topic—and perhaps not in the way you’d expect.

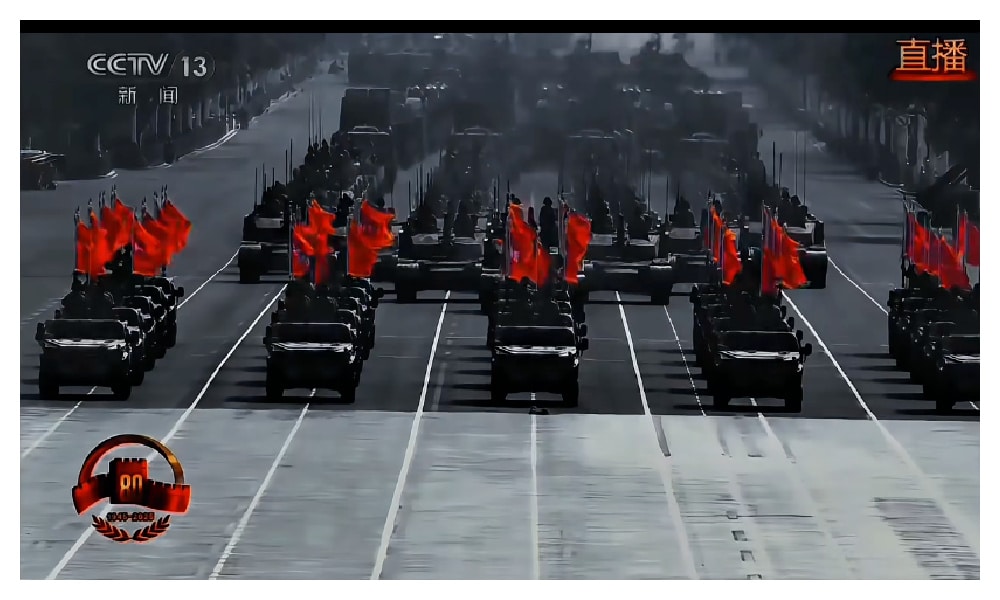

In the past week following the military parade, Chinese social media remained filled with discussions about the much-anticipated September 3 V-Day parade, a spectacle that had been hyped for weeks and watched by millions across the country.

That morning, Chinese leader Xi Jinping, accompanied by his wife Peng Liyuan, welcomed international guests on the red carpet. When Xi arrived at Tiananmen Square alongside Russian President Vladimir Putin and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, office phone calls across the country quieted, and school classes paused to tune in to one of China’s largest-ever military parades along Chang’an Avenue in Beijing, held to commemorate China’s victory over Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

As tanks rolled and jets thundered overhead, and state media outlets such as People’s Daily and Xinhua livestreamed the entire event, many different details—from what happened on Tiananmen Square to who attended, and what happened before and after, both online and offline—captured the attention of netizens.

Amid all the discussions online, one particularly hot conversation was about the visual coverage of the event, and focused on AFP (法新社), Agence France Press, the global news agency headquartered in Paris.

Typing “AFP” (法新社) into Weibo in the days after the parade pulled up a long list of hashtags:

- Has AFP released their shots yet?

- V-Day Parade through AFP’s lens

- AFP’s god-tier photo

- Did AFP show up for the parade?

The fixation may seem odd—why would Chinese netizens care so much about a French news agency?

Popular queries centered on AFP.

The story actually goes back to 2022.

In July of that year, on the anniversary of the Communist Party’s founding, one Weibo influencer (@Jokielicious) noted that while domestic photographers portrayed the celebrations as bright and triumphant, she personally preferred the darker, almost menacing image of Beijing captured by Western journalists. In her view, through their lens, China appeared more powerful—even a little terrifying.

The original post.

The post went viral. Soon, netizens began comparing more of China’s state media photos with those from Western outlets. One photo in particular stood out: Xinhua’s casual, cheerful shot of Chinese soldiers contrasted sharply with AFP’s cold, almost cinematic frame.

Same event, different vibe. Chinese social media users compared these photos of Xinhua (top) versus AFP (down). AFP photo shot by Fred Dufour.

Netizens joked that Xinhua had made the celebration look like the opening of a new hotel, while AFP had cast it as “the dawn of an empire.”

Gradually, what began as a dig at the bad aesthetics of state media turned into something else: a subtle shift in how Chinese netizens were rethinking their country’s international image.

Under the hashtag #ChinaThroughOthersLens (#老中他拍), netizens shared images of China as seen through the lenses of various Western media outlets.

This wasn’t the first time such talk had appeared. In the early days of the Chinese internet, people often spoke of the so-called “BBC filter.” The idea was that the BBC habitually put footage of China under a grayish filter, making its visuals give off a vibe of repression and doom, which many felt was at odds with the actual vibrancy on the ground. To them, it was proof that the West was bent on painting China as backward and gloomy.

These discussions have continued in recent years.

For example, on Weibo there were debates about a photo of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, shot by Peter Thomas for Reuters, and used in various Western media reports about Wuhan and Covid as early as 2021. The top image shows the photographer’s vantage point.

“Looks like a cockroach in the gutter,” one popular comment described it.

Top image by Chinese media, lower image by Peter Thomas/Reuters, and was used in various Western media reports about Wuhan and Covid since as early as 2021.

Another example is the alleged “smog filter” applied by Western media outlets to Beijing skies during the China visit of US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in 2024.

The alleged “smog filter” applied to Beijing skies during Blinken’s visit. Top image: Chinese media. Middle: BBC. Lower: Washington Post.

AFP, meanwhile, seemed to offer a different kind of ‘distortion.’

Netizens said AFP’s photos often had a low-saturation, high-contrast, solemn tone, with wide angles that made the scenes feel oppressive yet majestic. Over time, any photo with that look—whether taken by AFP or not—was dubbed the “AFP filter” (法新社滤镜).

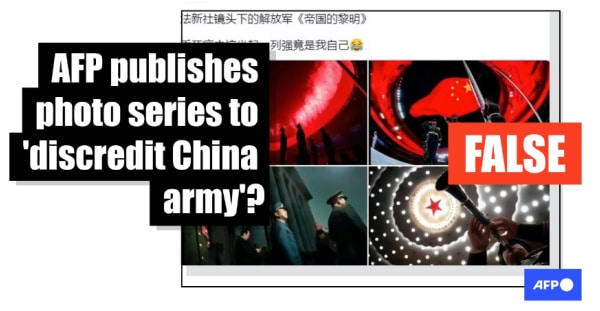

AFP has clarified multiple times that many of the viral examples weren’t even theirs—or that they were, but had been altered with an extra dark filter. They also refuted claims that AFP had published a photo series of Chinese soldiers titled “Dawn of Empire” to discredit China’s army.

AFP refuted claims that their photos discredited the Chinese army.

Nevertheless, the “AFP filter” label stuck. It became shorthand for a Western gaze that cast China not as impoverished or broken—as some claimed the “BBC filter” did—but as formidable, like a looming supervillain.

One running joke summed it up neatly: domestic shots are the festive version; Western shots are the red-tyrant version. And increasingly, netizens admitted they preferred the latter, commenting that while AFP shots often emphasize red to suggest authoritarianism, they actually like the red and what it stands for.

So, when this year’s V-Day came around, many were eager to see how AFP and other Western outlets would frame China as the dark, dangerous empire.

But when the photos dropped, the reaction was muted. They looked average. Some called them “disappointing.” “Where are the dark angles? Not doing it this time?” one blogger wondered. “Where’s the AFP hotline? I’d like to file a complaint!”

“Xinhua actually beat you this time,” some commented on AFP’s official Weibo account. Others agreed, putting the AFP photos and Xinhua photos side by side.

AFP photos on the left versus Xinhua photos on the right.

To make up for the letdown, people began editing the photos themselves—darkening the tones, adding dramatic shadows, and proudly labeling them with the tag “AFP filter” or calling it “The September 3rd Military Parade Through a AFP Lens” (法新社滤镜下的9.3阅兵). “Now that’s the right vibe,” they said: “I fixed it for you!”

Netizen @哔哔机 “AFP-fied” photos of the military parade by AFP.

Official media quickly picked up on the trend. Xinhua rolled out its own hashtags—#XinhuaAlwaysDeliversEpicShots (#新华社必出神图的决心#) and #XinhuaWins (#新华社秒了#)—and positioned itself as the true master of a new aesthetic narrative.

The message was clear: China no longer needs the Western gaze to frame itself as powerful or intimidating; it can do that on its own.

The “AFP v Xinhua” contest, the online movement to “AFP-ify” visuals, and the Chinese fandom around AFP’s moodier shots may have been wrapped in jokes and memes, but they also pointed to something deeper: the once “demonized” image of China that Western media pushed as threatening is now not only accepted by Chinese netizens, it’s embraced. Many have made it part of a confident, playful form of online patriotism, applauding the idea of being seen by the West as fearsome, even villainous, believing it amplifies China’s global authority.

As one netizen wrote: “I like it when we look like we crawl straight into their nightmares.”

Chinese journalist Kai Lei (@凯雷) suggested that these kinds of trends showed how the Chinese public plays an increasingly proactive role in shaping China’s global image.

By now, the AFP meme has become so strong that it doesn’t even require AFP anymore. Ultra-dramatic shots are simply called “AFP-level photos” (法新社级别).

For now, as many are enjoying the “afterglow” of the military parade, their appreciation for the AFP-style only seems to grow. As one Weibo user summed it up: “AFP tried to create a sense of oppression with dark, low-angle shots, but instead only strengthened the Chinese military’s aura of majesty.”

– By Ruixin Zhang and Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment6 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment6 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West