China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

The Legendary Lao Gan Ma: How Chili Sauce Billionaire Tao Huabi Became a ‘Chinese Dream’ Role Model

The story of Lao Gan Ma founder Tao Huabi.

Published

3 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT

You might know the chili sauce Lao Gan Ma, a household name in China. But perhaps you’re less familiar with the story behind the sauce and its founder, which has inspired millions of people and has made ‘Old Godmother’ Tao Huabi a notable figure in Chinese contemporary culture today. For many, the successful businesswoman and ‘chili sauce queen’ is an embodiment of the ‘Chinese dream.’

This is the “WE…WEI…WHAT?” column by Manya Koetse, original publication in German by Goethe Institut China (forthcoming), visit Yi Magazin: WE…WEI…WHAT? Manya Koetse erklärt das chinesische Internet.

Lao Gan Ma t-shirts, Lao Gan Ma phone covers, Lao Gan Ma bracelets, and even Lao Gan Ma airpod cases – Lao Gan Ma is more fashionable than ever in China today.

The celebrated brand is one of the country’s most well-known chili sauce labels, and it pops up in Chinese media and online culture every single day; not just because of its tasty condiments and other food products, but also because of the company’s remarkable history and evolution.

Besides the popularity of Lao Gan Ma’s crispy chili oil, it is the story of founder Tao Huabi (陶华碧) that plays a crucial role in the brand’s contemporary success. It is her face you see on the recognizable packaging design that has become a household product and is now also famous in many countries outside of China.

The iconic Lao Gan Ma, image via www.szmtzc.com

The brand name ‘Lao Gan Ma’ (老干妈) literally means ‘Old Godmother’ and refers to Tao Huabi herself. She is the creator of the famous chili sauces who has, over time, become the embodiment of the ‘Chinese dream.’ By following her own path and relying on her business instinct, Tao rose from poverty and became one of China’s richest women.

In order to explain why Tao Huabi is such an iconic figure in China today, let’s look at this famous female entrepreneur by highlighting the different stages of her Lao Gan Ma journey.

1: The Young Tao Huabi: “If I Hadn’t Been Strong, I Would’ve Starved”

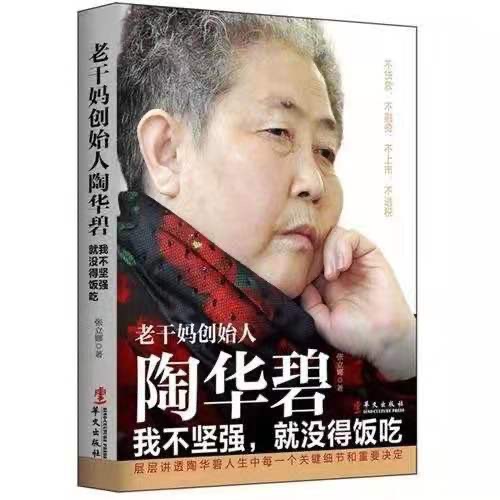

“There are many successful businesses entrepreneurs who have experienced hardships, but there are few whose starting point was as low as Tao’s.” These are the opening lines of a popular book about Tao Huabi, written by Zhang Lina (张丽娜), telling the story of her life.1

Tao Huabi was born in 1947 in a small village in Meitan County, Guizhou, one of China’s poorest provinces. She was the eighth daughter in her family (her parents had actually hoped to finally have a son), and her parents struggled to feed and clothe their children, let alone give them proper education. Tao was not taught how to read and write.

The biography about Tao Huabi describes how Tao spent her younger years chopping wood, cooking and farming. The title of the book is If I Hadn’t Been Strong, I Would’ve Starved (我不坚强,就没得饭吃), and it is telling of how Tao’s younger years were all about being hungry and finding ways to keep on going.

Tao Huabi’s biography, written by Zhang Nali. Image via Shanghuibs.

During the Great Chinese Famine (1959-1961), Tao dug for wild vegetables and tried various ways to eat plant roots, using whatever she had to try and make the little food they had taste better. This is how poverty and hunger drove the young Tao to make her very first chili sauce. The natural sauce, made from medicinal plants from the mountains and home-grown chili peppers, was loved by the entire family.

When Tao was 20 years old, she married her husband, who worked as an accountant with the local geological team. They had two sons together. But the happy life of the young family did not last long as just a few years into their marriage, Tao’s husband became seriously ill with liver disease.

Tao now found herself in an incredibly difficult situation; she was uneducated, illiterate, and had no official working experience. But she needed to provide income for her family as they had no money to cover her husband’s medical costs and pay for the food and education of their two sons. The 30-yuan monthly income of her husband was nowhere near enough to help the family.

The situation led Tao to head out of the countryside for the first time in her life to go to the city of Guangzhou to find a factory job as a migrant worker. She brought her own homemade chili sauce with her to the faraway city and used it to flavor her steamed buns when she couldn’t afford any other food. She also shared it with her co-workers, who found her chili sauce to be delicious.

Unfortunately, Tao’s efforts could not save her husband’s life. She soon became widowed and, heartbroken, had to return back to Guizhou to take care of her two young boys. Now that she had become the sole caregiver and provider of her family, she started selling rice curd and also set up a street stall selling vegetables at all hours of the day, often working until 4 in the morning.

Her passion for cooking kept following Tao wherever she went. One day, when Tao’s sons were already grown up, she visited a noodle shop after work and complained to the female shop owner that their cold noodles were not authentic enough. After Tao gave the lady her tips and tricks on how to improve the noodles using chili oil, she was offered a job at the noodle stall. The experience at the shop eventually gave Tao the idea to start her own business.

2: Inspirational Business Journey: “Selling the Flavor”

In 1989, when Tao was 42, she set up her own little “Economical Restaurant” (“实惠饭店”) in the Nanming District of Guiyang, Guizhou. Although she just served simple noodles, she mixed them with her own spicy hot sauce with soybeans. Tao was beloved in the neighborhood, where she became a ‘godmother’ to poor students whom she would always give discounts and some extra food.

With many local students and patrons visiting her little diner, the noodle shop business soon flourished, but not because of her noodles – it was the chili sauce that kept people coming back for more.

Tao Huabi came to understand the popularity of her condiments when customers came in to purchase the sauce by itself, without the noodles. One day, when her sauce had sold out, she found that customers would not even eat her noodles without the chili. When Tao learned that other noodle shops in the neighborhood were all doing good business by using her home-made sauce in their noodles, she finally realized the true potential of her product.

By the early 1990s, more truck drivers passed by Tao’s shop due to the construction of a new highway in the area. Tao took this as a chance to promote her condiments outside the realm of her own neighborhood and started giving out her sauces for free for the truckers to take home. This form of word-of-mouth marketing soon paid off when people from outside the city district came to visit Tao’s shop to buy her chili sauces and other condiments.

By late 1994, Tao had stopped selling noodles and had turned her little restaurant into a specialty store called ‘Tao’s Guiyang Nanming Food Shop’ (“贵阳南明陶氏风味食品店”), with the chili oil sauce being the number one product.

Two years later, at the age of 49, Tao took the plunge to rent a house in Guiyang, recruited forty workers, and set up her own sauce factory called ‘Old Godmother’: ‘Lao Gan Ma‘ (老干妈). Since the factory initially had no machines, the chili chopping was all done manually. Tao herself, wearing her apron, would also cut chilis at the factory tables together with her workers.

In 1997, the company was officially listed and open for business. Although Tao never had any formal education, she turned out to have a natural talent for managing her flourishing company. Tao’s two sons later also joined the Lao Gan Ma company.

Although the Lao Gan Ma brand became successful almost immediately after its launch, Tao Huabi still struggled for years as a handful of competitors launched fake Lao Gan Ma sauces with similar packaging, and nearly ruined her business. In 2001, when Tao Huabi was 54, the high court in Beijing finally ruled that other similar products could not use the “Lao Gan Ma” name nor imitate her packages. She received 400,000 RMB in compensation ($60,000).

Tao Huabi in her factory, image via Sohu.com.

Lao Gan Ma eventually employed over 2000 factory workers and became the largest producer and seller of chili products in China, reaching a point where the company produced 1.3 million bottles of chili sauce every day. Besides the iconic Fried Chili in Oil and Chili Crisp Sauce, Lao Gan Ma also produces Black Beans Chili Sauce, Tomato Chili Sauce, hot pot soup base, and other condiments.

By now, Tao’s ‘chili empire’ has gone international, as her condiments are sold from the USA to Africa. Tao Huabi once famously said that she does not know all the countries outside of China where Lao Gan Ma is sold, but that she does know that Lao Gan Ma is sold wherever there are Chinese people.

In 2019, Lao Gan Ma was selected as one of the top 100 brands in China, together with other famous national brands such as China Mobile, Huawei, Tik Tok, Tsingtao, and Alibaba.

Lao Gan Ma packaging, image via Taobao.

What is striking about the Lao Gan Ma business model is that it does not follow the usual marketing strategy tactics. The company rarely advertises, there are no celebrity endorsements, no social media accounts or campaigns, the website hasn’t been updated for years, and the Lao Gan Ma packaging has never modernized: it’s been the same old-fashioned logo for decades.

It is a marketing strategy that follows Tao’s no-nonsense line of thinking: if your product is good enough, people will buy it again. “We’re selling the flavor, not the packaging,” Tao herself once said.

3: The Old Godmother: “Labor Builds the Chinese Dream”

In the eyes of many, Tao Huabi is an embodiment of the ‘Chinese dream.’ A few years ago, Chinese state broadcaster CCTV produced a TV series titled “Labor Builds the Chinese Dream” (劳动铸就中国梦), and one of its episodes featured Tao Huabi, who is now 74 years old.

The main narrative of the documentary is that all people built on a country’s wealth together with each other as a collective goal – not an individual one. The idea of the ‘China Dream’ has been especially ubiquitous in Chinese official media since Xi Jinping became president in 2013. The concept refers to “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” In his first address to the nation in March of 2013, Xi emphasized that in order to realise the “Chinese road”: “(..) we must spread the Chinese spirit, which combines the spirit of the nation with patriotism as the core and the spirit of the time with reform and innovation as the core.”

Tao’s story fits this idea of the Chinese shared ‘road to prosperity’ dream. She started out poor but created her own business in spite of all obstacles. Along the way, she was always prepared to help out others while she herself rarely relied on her network or other people’s money to reach her goals.

Throughout her business journey, Tao has stayed true to her province, earning her the “Miracle of Guizhou” nickname. Despite the many offers she had throughout her career to set up her business elsewhere, she always refused to leave her home base – much to the delight of local government officials who have continuously shown their support for Tao. The businesswoman is a blessing for the province; not just because her brand has become known as a unique ‘product of Guizhou’, but mainly because she offers employment to nearly 5000 staff members, and directly and indirectly generates income for ten-thousands of local farmers.

Tao is also a Party member, and she is politically active as, among others, a representative of the Standing Committee of the Guizhou Provincial People’s Congress. She attended the National People’s Congress in Beijing multiple times.

Tao Huabi at the Two Sessions, photo via Sohu.com.

While Lao Gan Ma is one of China’s national brands, Tao Huabi is often also seen as a patriotic entrepreneur. Lao Gan Ma’s condiments are much more expensive outside in foreign countries than in China. While a two-pack of Lao Gan Ma is sold for only 9.9 yuan ($1.5) on Chinese e-commerce platform Taobao, the same pack is sold in the US for 13 up to 18 dollars on the American Amazon: eight to twelve times more expensive than the Chinese price. When asked about the enormous Lao Gan Ma price difference between China and other countries, Tao said: “I’m Chinese. I don’t make money off of Chinese people. I want to sell Lao Gan Ma to foreign countries and make money off of foreigners.”

Lao Gan Ma’s popularity outside of China has risen over the past decade. On Facebook, there is even a public group called “The Lao Gan Ma (老干妈) Appreciation Society,” where the group members (over 4000!) share their love for the brand.

Examples of Tao Huabi featured in fashion and accessories. Tao Huabi as a fashion icon?!

Meanwhile, on Chinese social media platform Weibo, Lao Gan Ma and Tao Huabi’s story often pop up in people’s posts: “Old Godmother is an example that you can still make it in life without any education.”

Perhaps there is no better person to embody the Chinese dream than Tao Huabi, who has experienced life in China from so many different angles. A poor farmer’s daughter, a young struggling widow, a migrant factory worker, a loving mother, a roadside peddler, a business manager, a loyal Party member, and even an unexpected fashion icon – Tao Huabi has seen and been it all. There is one thing she will always be: China’s chili sauce queen.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

1 Zhang Nali 张丽娜. 2019 (2016). Tao Huabi, Founder of Lao Gan Ma: If I Wouldn’t Have Been Strong, I Would’ve Starved [老干妈创始人陶华碧 我不坚强就没得饭吃] (in Chinese). Beijing: Chinese Publishing House. ISBN 978-7-5075-4451-0.

Featured image by Ama for Yi Magazin.

This text was written for Goethe-Institut China under a CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0-DE license (Creative Commons) as part of a monthly column in collaboration with What’s On Weibo.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

Published

2 months agoon

June 8, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

JD.com’s 618 shopping festival is driving down book prices to such an extent that it has prompted a boycott by Chinese publishers, who are concerned about the financial sustainability of their industry.

When June begins, promotional campaigns for China’s 618 Online Shopping Festival suddenly appear everywhere—it’s hard to ignore.

The 618 Festival is a product of China’s booming e-commerce culture. Taking place annually on June 18th, it is China’s largest mid-year shopping carnival. While Alibaba’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival has been taking place on November 11th since 2009, the 618 Festival was launched by another Chinese e-commerce giant, JD.com (京东), to celebrate the company’s anniversary, boost its sales, and increase its brand value.

By now, other e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Pinduoduo have joined the 618 Festival, and it has turned into another major nationwide shopping spree event.

For many book lovers in China, 618 has become the perfect opportunity to stock up on books. In previous years, e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Dangdang (当当) would roll out tempting offers during the festival, such as “300 RMB ($41) off for every 500 RMB ($69) spent” or “50 RMB ($7) off for every 100 RMB ($13.8) spent.”

Starting in May, about a month before 618, the largest bookworm community group on the Douban platform, nicknamed “Buying Like Landsliding, Reading Like Silk Spinning” (买书如山倒,看书如抽丝), would start buzzing with activity, discussing book sales, comparing shopping lists, or sharing views about different issues.

Social media users share lists of which books to buy during the 618 shopping festivities.

This year, however, the mood within the group was different. Many members posted that before the 618 season began, books from various publishers were suddenly taken down from e-commerce platforms, disappearing from their online shopping carts. This unusual occurrence sparked discussions among book lovers, with speculations arising about a potential conflict between Chinese publishers and e-commerce platforms.

A joint statement posted in May provided clarity. According to Chinese media outlet The Paper (@澎湃新闻), eight publishers in Beijing and the Shanghai Publishing and Distribution Association, which represent 46 publishing units in Shanghai, issued a statement indicating they refuse to participate in this year’s 618 promotional campaign as proposed by JD.com.

The collective industry boycott has a clear motivation: during JD’s 618 promotional campaign, which offers all books at steep discounts (e.g., 60-70% off) for eight days, publishers lose money on each book sold. Meanwhile, JD.com continues to profit by forcing publishers to sell books at significantly reduced prices (e.g., 80% off). For many publishers, it is simply not sustainable to sell books at 20% of the original price.

One person who has openly spoken out against JD.com’s practices is Shen Haobo (沈浩波), founder and CEO of Chinese book publisher Motie Group (磨铁集团). Shen shared a post on WeChat Moments on May 31st, stating that Motie has completely stopped shipping to JD.com as it opposes the company’s low-price promotions. Shen said it felt like JD.com is “repeatedly rubbing our faces into the ground.”

Nevertheless, many netizens expressed confusion over the situation. Under the hashtag topic “Multiple Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Book Promotions” (#多家出版社抵制618图书大促#), people complained about the relatively high cost of physical books.

With a single legitimate copy often costing 50-60 RMB ($7-$8.3), and children’s books often costing much more, many Chinese readers can only afford to buy books during big sales. They question the justification for these rising prices, as books used to be much more affordable.

Book blogger TaoLangGe (@陶朗歌) argues that for ordinary readers in China, the removal of discounted books is not good news. As consumers, most people are not concerned with the “life and death of the publishing industry” and naturally prefer cheaper books.

However, industry insiders argue that a “price war” on books may not truly benefit buyers in the end, as it is actually driving up the prices as a forced response to the frequent discount promotions by e-commerce platforms.

China News (@中国新闻网) interviewed publisher San Shi (三石), who noted that people’s expectations of book prices can be easily influenced by promotional activities, leading to a subconscious belief that purchasing books at such low prices is normal. Publishers, therefore, feel compelled to reduce costs and adopt price competition to attract buyers. However, the space for cost reduction in paper and printing is limited.

Eventually, this pressure could affect the quality and layout of books, including their binding, design, and editing. In the long run, if a vicious cycle develops, it would be detrimental to the production and publication of high-quality books, ultimately disappointing book lovers who will struggle to find the books they want, in the format they prefer.

This debate temporarily resolved with JD.com’s compromise. According to The Paper, JD.com has started to abandon its previous strategy of offering extreme discounts across all book categories. Publishers now have a certain degree of autonomy, able to decide the types of books and discount rates for platform promotions.

While most previously delisted books have returned for sale, JD.com’s silence on their official social media channels leaves people worried about the future of China’s publishing industry in an era dominated by e-commerce platforms, especially at a time when online shops and livestreamers keep competing over who has the best book deals, hyping up promotional campaigns like ‘9.9 RMB ($1.4) per book with free shipping’ to ‘1 RMB ($0.15) books.’

This year’s developments surrounding the publishing industry and 618 has led to some discussions that have created more awareness among Chinese consumers about the true price of books. “I was planning to bulk buy books this year,” one commenter wrote: “But then I looked at my bookshelf and saw that some of last year’s books haven’t even been unwrapped yet.”

Another commenter wrote: “Although I’m just an ordinary reader, I still feel very sad about this situation. It’s reasonable to say that lower prices are good for readers, but what I see is an unfavorable outlook for publishers and the book market. If this continues, no one will want to work in this industry, and for readers who do not like e-books and only prefer physical books, this is definitely not a good thing at all!”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese Sun Protection Fashion: Move over Facekini, Here’s the Peek-a-Boo Polo

From facekini to no-face hoodie: China’s anti-tan fashion continues to evolve.

Published

2 months agoon

June 6, 2024

It has been ten years since the Chinese “facekini”—a head garment worn by Chinese ‘aunties’ at the beach or swimming pool to prevent sunburn—went international.

Although the facekini’s debut in French fashion magazines did not lead to an international craze, it did turn the term “facekini” (脸基尼), coined in 2012, into an internationally recognized word.

The facekini went viral in 2014.

In recent years, China has seen a rise in anti-tan, sun-protection garments. More than just preventing sunburn, these garments aim to prevent any tanning at all, helping Chinese women—and some men—maintain as pale a complexion as possible, as fair skin is deemed aesthetically ideal.

As temperatures are soaring across China, online fashion stores on Taobao and other platforms are offering all kinds of fashion solutions to prevent the skin, mainly the face, from being exposed to the sun.

One of these solutions is the reversed no-face sun protection hoodie, or the ‘peek-a-boo polo,’ a dress shirt with a reverse hoodie featuring eye holes and a zipper for the mouth area.

This sun-protective garment is available in various sizes and models, with some inspired by or made by the Japanese NOTHOMME brand. These garments can be worn in two ways—hoodie front or hoodie back. Prices range from 100 to 280 yuan ($13-$38) per shirt/jacket.

The no-face hoodie sun protection shirt is sold in various colors and variations on Chinese e-commerce sites.

Some shops on Taobao joke about the extreme sun-protective fashion, writing: “During the day, you don’t know which one is your wife. At night they’ll return to normal and you’ll see it’s your wife.”

On Xiaohongshu, fashion commenters note how Chinese sun protective clothing has become more extreme over the past few years, with “sunburn protection warriors” (防晒战士) thinking of all kinds of solutions to avoid a tan.

Although there are many jokes surrounding China’s “sun protection warriors,” some people believe they are taking it too far, even comparing them to Muslim women dressed in burqas.

Image shared on Weibo by @TA们叫我董小姐, comparing pretty girls before (left) and nowadays (right), also labeled “sunscreen terrorists.”

Some Xiaohongshu influencers argue that instead of wrapping themselves up like mummies, people should pay more attention to the UV index, suggesting that applying sunscreen and using a parasol or hat usually offers enough protection.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Godfree Roberts

August 23, 2021 at 8:44 am

“During the Great Chinese Famine (1959-1961)”??

There was no Great Chinese Famine between 1959-1961. There were three difficult years, but nobody starved to death.

There was a Great Chinese Famine in 1942, during which millions starved to death, but that’s another matter.

There is a claimed, Great Famine in 1959-61, but the claims lack evidence, motive, or explanation and the book by the principal claimant, Frank Dikotter, is untrustworthy–even on its face. The cover image of a starving Chinese child was taken in 1942 (because, the author explained, “I couldn’t find any pictures of starvation from 1959-60).

There WAS an El Nino event from 1959-60 and there WAS an American embargo on exporting grain to China–designed to starve the country into submission, but even the CIA admitted that it had not failed:

April 4, 1961: The Chinese Communist regime is now facing the most serious economic difficulties it has confronted since it concentrated its power over mainland China. As a result of economic mismanagement, and especially of two years of unfavorable weather, food production in 1960 was hardly larger than in 1957, at which time there were about 50 million fewer Chinese to feed. Widespread famine does not appear to be at hand. Still, in some provinces, many people are now on a bare subsistence diet, and the bitterest suffering lies immediately ahead, in the period before the July harvests. The dislocations caused by the ‘Leap Forward’ and the removal of Soviet technicians have disrupted China’s industrialization program. These difficulties have sharply reduced the rate of economic growth during 1960 and have created a severe balance of payments problem. Public morale, especially in rural areas, is almost certainly at its lowest point since the Communists assumed power, and there have been some instances of open dissidence.

May 2, 1962: The future course of events in Communist China will be shaped largely by three highly unpredictable variables: the wisdom and realism of the leadership, the level of agricultural output, and the nature and extent of foreign economic relations. During the past few years, all three variables have worked against China. In 1958, the leadership adopted a series of ill-conceived and extremist economic and social programs; in 1959, there occurred the first of three years of bad crop weather; and in 1960, Soviet economic and technical cooperation was largely suspended. The combination of these three factors has brought economic chaos to the country. Malnutrition is widespread, foreign trade is down, and industrial production and development have dropped sharply. No quick recovery from the regime’s economic troubles is in sight.

Ridiculing the Great Leap Forward as ‘The Great Leap Backward,’ Edgar Snow confirmed the CIA’s findings:

Were the 1960 calamities as severe as reported in Peking, ‘the worst series of disasters since the nineteenth century,’ as Chou En-lai told me? The weather was not the only cause of the disappointing harvest, but it was undoubtedly a major cause. With good weather, the crops would have been ample; without it, other adverse factors I have cited–some discontent in the communes, bureaucracy, transportation bottlenecks–weighed heavily. Merely from personal observations in 1960, I know that there was no rain in large areas of northern China for 200-300 days. I have mentioned unprecedented floods in central Manchuria where I was marooned in Shenyang for a week …while eleven typhoons struck northeast China–the largest number in fifty years, and I saw the Yellow River reduced to a small stream. Throughout 1959-1962, many Western press editorials continued referring to ‘mass starvation’ in China and continued citing no supporting facts. As far as I know, no report by any non-Communist visitor to China provides an authentic instance of starvation during this period. Here I am not speaking of food shortages, or lack of surfeit, to which I have made frequent reference, but of people dying of hunger, which is what ‘famine’ connotes to most of us, and what I saw in the past.

Felix Greene, too, traveled throughout China in 1960:

With the establishment of the new Government in Peking in 1949, two things happened. First, starvation–death by hunger–ceased in China. There have been food shortages–and severe ones, but no starvation–a fact fully documented by Western observers. The truth is that the sufferings of the ordinary Chinese peasant from war, disorder, and famine have been immeasurably less in the last decade than in any other decade in the century.

Sky

March 13, 2024 at 6:53 pm

It is Zhang Li Na not Zhang Nali.

Manya

March 25, 2024 at 1:17 pm

Adjusted, thanks!