China Digital

Top 8 Scams in China to Watch Out for (2018)

From oldskool scams to WeChat scams – people are still falling for this every single day.

Published

7 years agoon

By

Gabi Verberg

As times change, so do scams. In an age of smartphones and social media, Chinese scammers are more prone to abandon old tricks and use new technology for their swindling business. But in a time of more digital scams, there are also still scammers who use people’s inexperience and desperation to earn money by simply fooling them on the streets. Here’s a top 8 of 2018 [check out top 10 China scams in 2015 here].

With the rapidly increasing number of online transactions in China, the persisting problem of counterfeit money scams in China may now be less of a problem than it was before. But other scams are on the rise.

Although people are now less vulnerable to scams involving cash money, services as WeChat wallet and Alipay are also not without peril. Over the years, scammers have developed numerous ways to cheat people and steal money from WeChat or Alipay wallets.

From infecting smartphones with viruses, to letting people “voluntarily” hand over their personal information, scammers have found ways to trick people from all ages and all layers of society.

As a follow-up to an earlier top 10 we did on scams in China, What’s on Weibo has compiled a list of 8 scams that are recently trending on social media or in the Chinese newspapers.

#1 WeChat Scams: Hacking Accounts

With over 800 million users of WeChat Pay in China, WeChat users are a lucrative target for scammers. In recent years, there have been various cases of WeChat scams, in which hackers of private accounts pretend to be a friend or family member, and convince others to send them money.

Last summer, the news went viral of Chinese parents becoming a victim of scammers pretending to be their children.

These hackers, using the children’s accounts, told ‘their parents’ that they had to attend a special course or lecture, often held by professors from renowned universities such as Tsinghua or Beijing University. Once the scammer convinced the parent to pay for the extra curriculum activity, the scammers send the contact information of the “teachers” in charge of the event.

Once the parents added the “teachers'” to WeChat and transferred the money, the scammers continued to get parents to pay for all sorts of things such as service fees, registration fees, supply fees, etc.

In other more extreme examples, parents were asked to follow a link to complete the payment. The link installed a virus onto the parent’s phone, allowing the scammer to have full access to the victim’s WeChat wallet.

#2 Voice Scams: Imitation Champions

Another rising problem that China and many other countries are currently facing is the issue of so-called ‘voice scams.’ Often done through WeChat, scammers collect a person’s voice messages and then pretend to be this person by imitating his or her voice.

The scammers will then make a fake WeChat account that is an exact copy of the one they are imitating. They will contact family members and friends of the person they are imitating, and ask to borrow money. Because the voices sound so much alike, they often win the trust of people and get them to send the money.

Image via http://www.sohu.com/a/201988031_689129

In one extreme case, a young man’s voice was imitated so well that scammers were able to convince the man’s mother that her son was abducted. In a complete panic, the mother transferred the demanded ransom.

In all cases, the police advise people to always confirm face-to-face with the other person before sending money. Additionally, they also warn people should be on their guard sharing voice messages or any other form of personal information with strangers.

#3 Delivery Scams: Too Many Packages

As easy and convenient online shopping might seem, it is not without danger. Just as with WeChat scams, there are many ways in which scammers will try to find weak points within the system.

One of the issues that makes people more vulnerable to scams within the world of online shopping is that many people order so many products online, that they are more likely to believe that a package is theirs – even if they have never actually ordered it.

The most common online shopping scam involves “cash on delivery,” where the courier asks people to pay upon delivery. Once opening the packaging, people discover their package is actually empty.

In another version, scammers will first call the victim pretending to be their neighbor. They will ask them to do them a favor and accept a package, since they are not able to be home on time to accept it themselves. This way, people are even more likely to accept the package.

In yet another scam, often referred to as the “compensation scam,” scammers call customers and pretend to be employees of a delivery company. On the phone, they will tell that one of their carriers accidentally lost or damaged the ordered product and that they want to compensate for the loss. The only thing the victim has to do is to fill out an online “compensation form” for which personal information and bank information is required. With this information, the scammers can easily break into their victim’s bank account.

In some cases, scammers ask customers to add a WeChat account so they can be compensated for their ‘loss’. In the final step, they will require them to scan a QR-code, or click a link, and to transfer a small ‘service’ fee. Once they have transferred the fee, a virus will be installed on their phone, allowing the scammers to access their WeChat wallet.

Delivery companies advise their customers not to accept any package if they are not sure they have actually ordered it. With cash delivery packages, customers are advised to always check the package before sending the courier away.

About lost or damaged packages: delivery companies will never ask you to fill out a compensation form or share any personal or bank information. In case the delivery company loses or damages your order, the company you bought it from will then inform you and transfer the money back to your bank account.

#4 Catching Red Envelopes

Snatching ‘red envelopes’, qiǎng hóngbāo (抢红包) in Chinese, originated from China’s long-standing tradition of giving red envelopes to children to celebrate the Chinese New Year.

However, as the tradition of giving red envelopes is transforming from offline to online, the new phenomenon of ‘snatching red envelopes’ has also become more ubiquitous.

Through WeChat, people can send red envelopes to a group of friends: the (few) people who are first in opening that envelope will then receive an amount of money. Companies often use this feature as a marketing tool.

Scammers also make use of this red envelope craze. The ‘red envelop scam’ starts with a message via one of one’s WeChat contacts, reading something like: “I just discovered a group and the host of the group is going crazy! He keeps sending red envelopes! Add yourself to the group and snatch some envelopes.” This message will often be followed by a message telling you that you will be rewarded money when you add more people to the group.

Within a few minutes, the group chat has added hundreds of people. As members increase, the group owner will encourage people to add more people to the group by keeping on sending red envelopes. In the meantime, the group owner will send out a message saying that the ones who already opened an envelope are registered. In case they do not add ten people to the group within 30 minutes they will be kicked out. As for those who add 20 people to the group within half an hour, they will be rewarded even more money.

This way, people will keep adding contacts to the group. And because it is not allowed to talk in the group, people are also not able to warn each other of its potential dangers, because, at this point, the red envelopes will actually change into QR codes – the group owner will post a message saying that his transactions surpassed the transactions limit of the day and that if people want to continue receiving money, they will have to scan the QR-code and pay the symbolic amount of one yuan ($0.14). If they do so, they are promised to be rewarded with a high amount of money.

Once these people pay the one yuan, they have been scammed: through the QR code, the scammers have installed a virus into their WeChat, allowing them to empty their WeChat wallet. There are many versions to this kind of “red envelope” and “free money” scams. To avoid being scammed, it is best to remember that there is no such thing as getting money for nothing – there’s always a price to be paid.

#5 Winning Lottery-Ticket Scam

For the “winning lottery ticket scam,” scammers play with people’s minds. And no matter how simple this trick may seem, it is a worldwide phenomenon.

The scam starts with the victim finding a lottery ticket that has intentionally been placed somewhere. Since the owner of the lottery ticket is nowhere to be found, most people finding the ticket then call the number registered on the ticket to find out whether or not the ticket won a price. And, of course, they are told that the found ticket is indeed a ‘prize-winning’ ticket.

Because people, at this point, are so excited about their unexpected ‘luck’, they often no longer keep their mind straight. The scammer on the phone will inform the lucky finder that they only need to pay a handling fee before they can receive their prize money.

In some cases, the scammers even convince the victim to pay an income tax before receiving the prize money. Once the lucky winner paid the handling fee or income tax [via WeChat or Alipay], the connection will be cut off, and of course, the victim will never get the prize.

#6 Found Wallet Scam

You are walking outside, and suddenly you find a wallet on the streets – the owner is already out of sight. As you stand still with the wallet in your hand, a stranger comes up to you accusing you of stealing money from that found wallet.

It is a scam that frequently occurs in China, and it is easy to imagine that someone who just found a wallet might feel awkward about the situation, especially when accused of trying to steal the money inside of the wallet.

While explaining that they did not intend on trying to steal money, the stranger will intimidate the finder to give him some of the cash inside to settle the matter. Many people will do so in order to avoid a public scene.

But that is not the end of the scam, as the ‘owner’ of the wallet will then suddenly pop up, asking for his wallet, and discovering that some money inside is missing. The ‘finder’ will then compensate for that loss to get themselves out of the humiliating situation.

Obviously, the two men – the ‘bad guy’ demanding the money and the person who lost the wallet – work together in setting people up like this. Police advise people who find a wallet to turn it in at the closest police station.

Netease has reconstructed the scam on a video here.

#7 Fake Job Scam

One of the most common scams in China nowadays is the so-called “fake job scam.” Scammers will place fake job ads, and meet responders outside a company office for their ‘job interview.’

In most cases, the applicant is ‘hired’ immediately after the job interview. But before they can get to work, they first have to pass a medical test at a designated ‘research center.’ The victim is then told that he has to pay for the transportation and medical fees, and that the money will be reimbursed at the end of the first working month.

In many cases, victims also pay for service costs and forward a deposit for cards that allow them into the office, etc. When all these fees are paid, the ‘company’ can no longer be contacted and is suddenly untraceable.

To avoid people from getting tricked into these fake job scams, police advise to only reply to job ads with a registered phone number and official company address.

#8 Trap Loans: A Mountain of Loans

The problem of ‘trap loans’ has received much media attention in China over recent years. Earlier this year the story of one woman went viral; she borrowed 2,000 yuan ($292) and ended up with a 150,000 yuan ($21.872) debt two months later.

She is just of among many victims of China’s “trap loans.” In various other cases reported by the media, people end up in such huge debts and depression, that they take their own lives.

Scammers specifically target people who are temporarily short of cash. It often starts with an individual lender offering a quick loan, only for a few days, in the name of a small loaning company (小额贷款公司). Once the person tells the loaning company they need credit, a lender will come up with a contract that has blank spaces in them. The contract is often so long and complicated that people don’t read it through carefully enough.

When the contract is signed, the loaning company will insert extra information into the blank spaces of the signed contract. They will, for example, change the time you are allowed to borrow money, the interest rate, or the name of the lender.

In the next phase, the loaning company will purposely make the borrower breach the contract by, for example, temporarily being out of service or unreachable, so that the borrower is not able to pay off his debts as recorded in the agreement. They will then face the sum of accumulated interest on the borrowed money, and fines for overdue payments.

Around this time, the lender will introduce the borrowers to another loaning company where they can take out more loans to pay off the debts of the first contract. This can go on for many years and many contracts. The borrower will not be able to repay the entire sum of borrowed money, so keeps on paying huge interest rates and fines for overdue payments.

There have been reports of trap loans in various forms such as campus loans, where students are tricked into ‘easy money loans’ by on-campus advertisements; or naked loans, where scammers demand people to send a (partly) nude picture of themselves holding their ID as collateral. Often this photo will later be used to blackmail a person.

Want to read more? Also check out our previous ‘Top 10 Scams to Watch Out For in China‘.

By Gabi Verberg

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Gabi Verberg is a Business graduate from the University of Amsterdam who has worked and studied in Shanghai and Beijing. She now lives in Amsterdam and works as a part-time translator, with a particular interest in Chinese modern culture and politics.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform resurfaces in Africa, a new winter hotspot, why Chinese elites ‘run’ to Tokyo, and more.

Published

1 week agoon

November 21, 2025

🌊 Signals — Week 47 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China, Signals highlights slower trends and online currents behind the daily scroll. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Different from the China Trend Watch (check the latest one here if you missed it), this edition, part of the new Signals series, is about the slower side of China’s social media: the recurring themes and underlying shifts that signal broader trends beyond the quick daily headlines. Together with the deeper dives, the three combined aim to give you clear updates and a fuller overview of what’s happening in China’s online conversations & digital spaces.

For the coming two weeks, I’ll be traveling from Beijing to Chongqing and beyond (more on that soon) so please bear with me if my posting frequency dips a little. I’ll be sure to pick it up again soon and will do my best to keep you updated along the way. In the meantime, if you know of a must-try hotpot in Chongqing, please do let me know.

In this newsletter: Hasan Piker’s controversial China tour, a Chinese school uniform in Angola, a new winter hotspot, discussions on what happens to your Wechat after you die, why Chinese elites rùn to Tokyo, and more. Let’s dive in.

- 💰 The richest woman in China, according to the latest list by Hurun Research Institute, is the “queen of pharmaceuticals” Zhong Huijuan (钟慧娟) who has accumulated 141 billion yuan (over 19 billion USD). Women account for over 22% of Chinese billionaires (those with more than 5 billion RMB), underscoring China’s globally leading position in producing wealthy female entrepreneurs.

- 🧩 What happens to your WeChat after you die? A user who registered for NetEase Music with a newly reassigned phone number unexpectedly gained access to the late singer Coco Lee’s (李玟) account, as the number had originally belonged to her. The incident has reignited debate over how digital accounts should be handled after death, prompting platforms like NetEase and Tencent to reconsider policies on long-inactive accounts and take stronger measures to protect them.

- 📱 Although millions of viewers swoon over micro-dramas with fantasy storylines where rich, powerful men win over the “girl next door” through money and status, Chinese regulators are now stepping in to curb exaggerated plots featuring the so-called “dominant CEO” (霸道总裁) archetype, signaling stricter oversight for the booming short drama market.

- ☕ A popular Beijing coffee chain calling itself “People’s Cafe” (人民咖啡馆), with its style and logo evoking nationalist visual nostalgia, has changed its name after facing criticism for building its brand – including pricey coffee and merchandise – on Mao era and state-media political connotations. The cafe is now ‘Yachao People’s Cafe’ (要潮人民咖啡馆).

- 👀 Parents were recently shocked to see erotic ads appear on the Chinese nursery rhymes and children’s learning app BabyBus (宝宝巴士), which is meant for kids ages 0–8. BabyBus has since apologized, but the incident has sparked discussions about how to keep children safe from such content.

- 🧧The 2026 holiday schedule has continued to be a big topic of conversation as it includes a 9-day long Spring Festival break (from February 15 to February 23), making it the longest Lunar New Year holiday on record. The move not only gives people more time for family reunions, but also gives a huge boost to the domestic travel industry.

Hasan Piker’s Chinese Tour & The US–China Content Honeymoon

Livestreamer Hasan Piker during his visit to Tiananmen Square flag-rising ceremony.

It’s not time for the end-of-year overviews just yet – but I’ll already say that 2025 was the US–China ‘honeymoon’ year for content creation. It’s when China became “cool,” appealing, and eye-grabbing for young Western social media users, particularly Americans. The recent China trip of the prominent American online streamer Hasan Piker fits into that context.

This left-wing political commentator also known as ‘HasanAbi’ (3 million followers on Twitch, recently profiled by the New York Times) arrived in China for a two-week trip on November 11.

Piker screenshot from the interview with CGTN, published on CGTN.

His visit has been controversial on English-language social media, especially because Piker, known for his criticism of America (which he calls imperialist), has been overly praising China: calling himself “full Chinese,” waving the Chinese flag, joining state media outlet CGTN for an interview on China and the US, and gloating over a first-edition copy of Quotations from Chairman Mao (the Little Red Book). He portrays China as heavily misrepresented in the West and as a country the United States should learn from.

Hasan Piker did an interview with CGTN, posing with Li Jingjing 李菁菁.

During his livestreaming tour, Hasan, who is nicknamed “lemonbro” (柠檬哥) by Chinese netizens, also joined Chinese platforms Bilibili and Xiaohongshu.

But despite all the talk about Piker in the American online media sphere, online conversations, clicks, and views within China are underwhelming. As of now, he has around 24,000 followers on Bilibili, and he’s barely a topic of conversation on mainstream feeds.

Piker’s visit stands in stark contrast to that of American YouTuber IShowSpeed (Darren Watkins), who toured China in March. With lengthy livestreams from Beijing to Chongqing, his popularity exploded in China, where he came to be seen by many as a representative of cultural diplomacy.

IShowspeed in China, March 2025.

IShowSpeed’s success followed another peak moment in online US–China cultural exchange. In January 2025, waves of foreign TikTok users and popular creators migrated to the Chinese lifestyle app Xiaohongshu amid the looming TikTok ban.

Initially, the mass migration of American users to Xiaohongshu was a symbolic protest against Trump and US policies. In a playful act of political defiance, they downloaded Xiaohongshu to show they weren’t scared of government warnings about Chinese data collection. (For clarity: while TikTok is a made-in-China app, it is not accessible inside mainland China, where Douyin is the domestic version run by the same parent company).

The influx of foreigners — who were quickly nicknamed “TikTok refugees” — soon turned into a moment of cultural celebration. As American creators introduced themselves, Chinese users welcomed them warmly, eager to practice English and teach newcomers how to navigate the app. Discussions about language, culture, and societal differences flourished. Before long, “TikTok refugees” and “Xiaohongshu natives” were collaborating on homework assignments, swapping recipes, and bonding through humor. It was a rare moment of social media doing what we hope it can do: connect people, build bridges, and replace prejudice with curiosity.

Some of that same enthusiasm was also visible during IShowSpeed’s China tour. Despite the tour inevitably getting entangled with political and commercial interests, much of it was simply about an American boy swept up in the high energy of China’s vibrant cities and everything they offer.

Different from IShowSpeed, who is known for his meme-worthy online presence, Piker is primarily known for his radical political views. His China enthusiasm feels driven less by cultural curiosity and more by his critique of America.

Because of his stances — such as describing the US as a police state — it’s easy for Western critics to accuse him of hypocrisy in praising China, especially after a brief run-in with security police while livestreaming at Tiananmen Square.

Seen in broader context, Piker’s China trip reflects a shift in how China is used in American online discourse.

Before, it was Chinese ‘public intellectuals’ (公知) who praised the US as a ‘lighthouse country’ (灯塔国), a beacon of democracy, to indirectly critique China and promote a Western modernization model. Later, Chinese online influencers showcased their lives abroad to emphasize how much ‘brighter the moon’ was outside China.

In the post-Covid years, the current reversed: Western content creators, from TikTok influencers to political commentators, increasingly use China to make arguments that are fundamentally about America.

Between these cycles, authentic cultural curiosity gets pushed to the sidelines. The TikTok-refugee moment in early January may have been the closest we’ve come in years: a brief window where Chinese and American users met each other with curiosity, camaraderie, and creativity.

Hasan’s tour, in contrast, reflects a newer phase, one where China is increasingly used as a stage for Western political identity rather than a complex and diverse country to understand on its own terms. I think the honeymoon phase is over.

“Liu Sihan, Your School Uniform Ended Up in Angola”: China’s Second-Hand Clothing in Africa

A Chinese school uniform went viral after a Chinese social media user spotted it in Angola.

“Liu Sihan, your schooluniform is hot in Africa” (刘思涵你的校服在非洲火了) is a sentence that unexpectedly trended after a Chinese blogger named Xiao Le (小乐) shared a video of a schoolkid in Angola wearing a Chinese second-hand uniform from Qingdao Xushuilu Primary School, that had the nametag Liu Sihan on it.

The topic sparked discussions about what actually happens to clothing after it’s donated, and many people were surprised to learn how widely Chinese discarded clothing circulates in parts of Africa.

Liu Sihan’s mother, whose daughter is now a 9th grader in Qingdao, had previously donated the uniform to a community clothing donation box (社区旧衣回收箱) after Liu outgrew it. She intended it to help someone in need, never imagining it to travel all the way to Africa.

In light of this story, one netizen shared a video showing a local African market selling all kinds of Chinese school items, including backpacks, and people wearing clothing once belonging to workers for Chinese delivery platforms. “In Africa, you can see school uniforms from all parts of China, and even Meituan and Eleme outfits,” one blogger wrote.

When it comes to second-hand clothing trade, we know much more about Europe–Africa and US–Africa flows than about Chinese exports, and it seems there haven’t been many studies on this specific topic yet. Still, alongside China’s rapid economic transformations, the rise of fast fashion, and the fact that China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of textiles, the country now has an enormous abundance of second-hand clothing.

According to a 2023 study by Wu et al. (link), China still has a long way to go in sustainable clothing disposal. Around 40% of Chinese consumers either keep unwanted clothes at home or throw them away.

But there may be a shift underway. Donation options are expanding quickly, from government bins to brand programs, and from second-hand stores to online platforms that offer at-home pickup.

Chinese social media users posting images of school/work uniforms from China worn by Africans.

As awareness grows around the benefits of donating clothing (reducing waste, supporting sustainability, and the emotional satisfaction of giving), donation rates may rise significantly. The story of Liu Sihan’s uniform, which many found amusing, might even encourage more people to donate. And if that happens, scenes of African children (and adults) wearing Chinese-donated clothes may become much more common than they now are.

Laojunshan: New Hotspot in Cold Winter

Images from Xiaohongshu, 背包里的星子, 旅行定制师小漾

Go to Zibo for BBQ, go to Tianshui for malatang, go to Harbin for the Ice Festival, cycle to Kaifeng for soup dumplings, or head to Dunhuang to ride a camel — over recent years, a number of Chinese domestic destinations have turned into viral hotspots, boosted by online marketing initiatives and Xiaohongshu influencers.

This year, Laojunshan is among the places climbing the trending lists as a must-visit spot for its spectacular snow-covered landscapes that remind many of classical Chinese paintings. Laojunshan (老君山), a scenic mountain in Henan Province, is attracting more domestic tourists for winter excursions.

Xiaohongshu is filled with travel tips: how to get there from Luoyang station (by bus), and the best times of day to catch the snow in perfect light (7–9 AM or around 6–6:30 PM).

With Laojunshan, we see a familiar pattern: local tourism bureaus, state media, and influencers collectively driving new waves of visitors to the area, bringing crucial revenue to local industries during what would otherwise be slower winter months.

WeChat New Features & Hong Kong Police on Douyin

🟦 WeChat has been gradually rolling out a new feature that allows users to recall a batch of messages all at once, which saves you the frantic effort of deleting each message individually after realizing you sent them to the wrong group (or just regret a late-night rant). Many users are welcoming the update, along with another feature that lets you delete a contact without wiping the entire chat history. This is useful for anyone who wants to preserve evidence of what happened before cutting ties.

🟦The Hong Kong Police Force recently celebrated its two-year anniversary on Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok), having accumulated nearly 5 million followers during that time. To mark the occasion, they invited actor Simon Yam to record a commemorative video for their channel (@香港警察). The presence of the Hong Kong Police on the Chinese app — and the approachable, meme-friendly way they’ve chosen to engage with younger mainland audiences — is yet another signal of Hong Kong institutions’ strategic alignment with mainland China’s digital infrastructure, a shift that has been gradually taking place. The anniversary video proved popular on Douyin, attracting thousands of likes and comments.

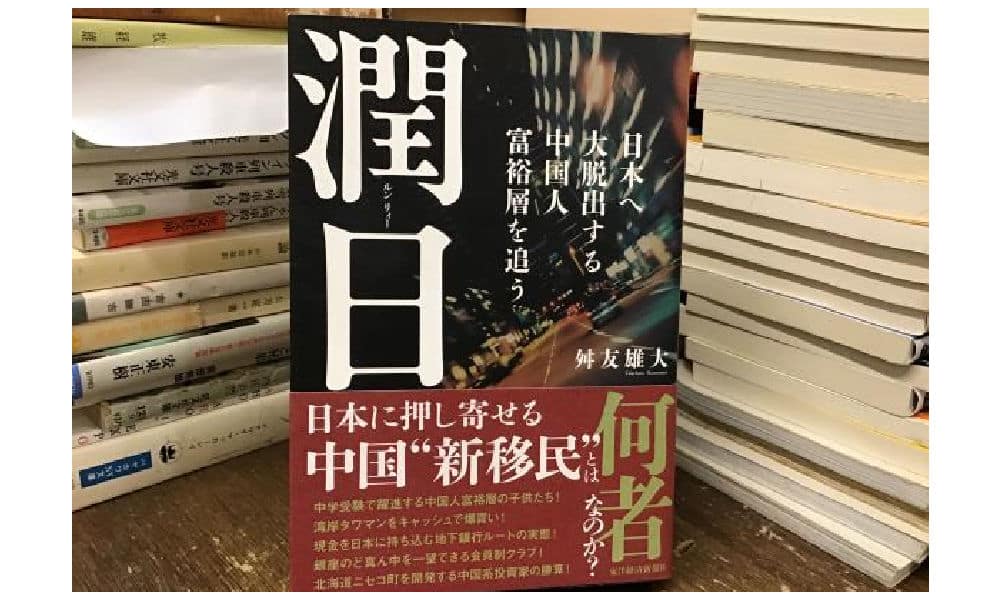

Why Chinese Elite Rùn to Japan (by ChinaTalk)

Over the past week, Japan has been trending every single day on Chinese social media in light of escalating bilateral tensions after Japanese PM Takaichi made remarks about Taiwan that China views as a direct military threat. The diplomatic freeze is triggering all kinds of trends, from rising anti-Japanese sentiment online and a ban on Japanese seafood imports to Chinese authorities warning citizens not to travel to Japan.

You’d think Chinese people would want to be anywhere but Japan right now — but the reality is far more nuanced.

In a recent feature in ChinaTalk, Jordan Schneider interviewed Japanese journalist & researcher Takehiro Masutomo (舛友雄大) who has just published a book about Japan’s new Chinese diaspora, explaining what draws Chinese dissidents, intellectuals, billionaires, and middle-class families to Tokyo.

The book is titled Run Ri: 潤日 Following the Footsteps of Elite Chinese Escaping to Japan (only available in Japanese and Traditional Chinese for now). (The word Rùn 润/潤, by the way, is Chinese online slang and meme expresses the desire to escape the country.)

A very interesting read on how Chinese communities are settling in Japan, a place they see as freer than Hong Kong and safer than the U.S., and one they’re surprisingly optimistic about — even more so than the Japanese themselves.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China Signals. For fast-moving trends and deeper dives, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you just so happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

A small housekeeping note:

This Eye on Digital China newsletter is co-published for subscribers on both Substack and the main site. If you’re registered on both platforms, you’ll receive duplicate emails — so if that bothers you, please pick your preferred platform and unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or email me.

First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

From China’s first soap opera Yearnings to the rise of AI-fueled nostalgia.

Published

5 months agoon

July 2, 2025

The year is 1990, and the streets of Beijing’s Fangshan District are eerily quiet. You can almost hear a pin drop in the petrochemical town, as tens of thousands of workers and their families huddle around their televisions, all tuned to the same channel for something groundbreaking: China’s very first soap opera, Yearnings (渴望 Kěwàng).

Yearnings tells the story of Liu Huifang (刘慧芳), a female factory worker from a traditional working-class family in Beijing, and her unlikely marriage to university graduate Wang Husheng (王沪生), who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Liu finds an abandoned baby girl, she adopts her and raises her as her own, against her husband’s wishes.

The couple is unaware that the foundling is actually the illegitimate child of Wang’s snobbish sister, Yaru. After Liu and Wang have a biological son, the marriage comes under further pressure, eventually leading to divorce. Liu is left as a single mother, raising two children on her own.

Still from Yearnings, via OurChinaStory.

Drawing inspiration from foreign dubbed television shows, Yearnings was produced as China’s first truly domestic, long-form indoor television drama. Spanning 50 episodes, the series traces a timeline from the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s through to the late 1980s—one of the most turbulent periods in modern Chinese history.

Before the series aired nationally on CCTV and achieved record viewership, the first station to air Yearnings in the Beijing region was the Yanshan Petrochemical TV Station (燕山石化电视台), China’s first major factory TV station (厂办电视台) located in Fangshan District.

Here, in this town of over 100,000, Yearnings garnered an astonishing and unprecedented 98% audience share. The series was truly groundbreaking and became a national sensation—not just because it was China’s first long-form television drama, or because it was a locally produced drama that challenged the long-standing monopoly of state broadcaster CCTV, but because Yearnings marked a major shift in television storytelling.

Until then, Chinese TV stories had always revolved around communist propaganda, or featured great heroes of the revolution. Yearnings, on the other hand, was devoid of political content and focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary people and their everyday struggles—love, desire, marital tension, single motherhood—topics that had never before been so openly portrayed on Chinese television.

The show’s creators had perfectly tapped into what was changing: the Communist Party was slowly withdrawing from private life, and people were beginning to see themselves less defined by their work unit and more by their home life—as consumers, as partners and parents, as citizens of a new China filled with aspirations for the future. Yearnings’ storyline was a reflection of that.

Chinese-Style “Nostalgia Core”

Yearnings marked a cultural turning point, coinciding with the rapid spread of TV sets in Chinese households. In 1992, economic reforms triggered a new era in which Chinese media became increasingly commercialized and thriving, before the arrival of the internet, social media, and AI tools once again changed everything.

Today, Yearnings still is a topic that often comes up in Chinese online media. On apps like Douyin, old scenes from Yearnings are reposted and receive thousands of shares.

📌 It’s emblematic of a broader trend in which more netizens are turning to “nostalgia-core.” In Chinese, this trend is known as “中式梦核” (Zhōngshì Mènghé), which literally means “Chinese-style dreamcore.”

Dreamcore is an internet aesthetic and visual style—popular in online communities like Tumblr and Reddit—that blends elements of nostalgia, surrealism, and subconscious imagery. Mixing retro images with fantasy, it evokes a sense of familiarity, yet often feels unsettling and deserted.

The Chinese-style dreamcore (中式梦核), which has become increasingly popular on platforms like Bilibili since 2023-2024, is different from its Western counterpart in how it incorporates distinctly Chinese elements and specifically evokes the childhood experiences of the millennial generation. Content tagged as “Chinese-style dreamcore” on Chinese social media is often also labeled with terms like “nostalgia” (怀旧), “childhood memories” (童年回忆), “when we were little” (小时候), and “Millennial Dream” (千禧梦).

According to the blogging account Yatong Local Life Observer (娅桐本地生活观察), the focus on the millennial childhood can be explained because the formative years of this generation coincided with a decade of rapid social change in China —leaving little in today’s modern cities that still evokes that era.

🌀 Of course, millennials in the West also frequently look back at their childhood and teenage years, particularly the 1980s and 1990s—a trend also embraced by Gen Z, who romanticize these years through media and fashion. In China, however, Gen Z is at the forefront of the “nostalgia-core” trend, reflecting on the 1990s and early 2000s as a distant, almost dreamlike past. This sense of distance is heightened by China’s staggering pace of transformation, modernization, and digitalization over the past decades, which has made even the recent past feel remote and irretrievable.

🌀 Another factor contributing to the trend is that China’s younger generations are caught in a rat race of academic and professional competition, often feeling overwhelmed by the fast pace of life and the weight of societal expectations. In this high-pressure environment—captured by the concept of “involution” (内卷)—young people develop various coping mechanisms, and digital escapism, including nostalgia-core, is one of them. It’s like a cyber-utopia (赛博乌托邦).

🌀 Due to the rise of AI tools available to the general public, Chinese-style nostalgia core has hit the mainstream because it’s now possible for all social media users to create their own nostalgic videos and images—bringing back the 1990s and early 2000s through AI-generated tools, either by making real videos appear more nostalgic or by creating entirely fictional videos or images that recreate scenes from those days.

So what are we seeing? There are images and videos of stickers kids used to love, visuals showing old classrooms, furniture, and children playing outside, accompanied by captions such as “we’re already so far apart from our childhood years” (example).

Images displayed in Chinese Dreamcore.

And notably, there are videos and images showing family and friends gathering around those old big TVs as a cultural, ritualized activity (see some examples here).

Stills from ‘nostalgia core’ videos.

These kinds of AI-generated videos depict a pre-mobile-era family life, where families and communities would gather around the TV—both inside and outside—from classrooms to family homes. The wind blows through the windows, neighbors crack sunflower seeds, and children play on the ground. Ironically, it’s AI that is bringing back the memories of a society that was not yet digitalized.

Nowadays, with dozens of short video apps, streaming platforms, and livestream culture fully mainstream in China—and AI algorithms personalizing feeds to the extreme—it sometimes feels like everyone’s on a different channel, quite literally.

In times like these, people long for an era when life seemed less complicated—when, instead of everyone staring at their own screens, families and neighbors gathered around one screen together.

There’s not just irony in the fact that it took AI for netizens to visualize their longing for a bygone era; there’s also a deeper irony in how Yearnings once represented a time when people were looking forward to the future—only to find that the future is now looking back, yearning for the days of Yearnings.

It seems we’re always looking back, reminiscing about the years behind us with a touch of nostalgia. We’re more digitalized than ever, yet somehow less connected. We yearn for a time when everyone was watching the same screen, at the same time, together, just like in 1990. Perhaps it’s time for another Yearnings.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Sources (other sources included in hyperlinks)

Koetse, Manya. 2016. “From Woman Warrior to Good Wife – Confucian Influences on the Portrayal of Women in China’s Television Drama.” In Stefania Travagnin (ed), Religion and Media in China. New York: Routledge.

Rofel, Lisa B. 1994. Yearnings: Televisual Love and Melodramatic Politics in Contemporary China. American Ethnologist 21(4):700-722.

Wang, Dan (汪丹). 2018. “《渴望》的艺术价值” [The Artistic Value of Yearnings].” Originally published in Beijing Daily (北京日报), October 12, 2018. Reprinted in Digest News (文摘报), October 20, 06 edition. Also see Sohu: 当年红遍大江南北的《渴望》.

Wang Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, a Chinese television soap opera with a message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Zhuge Kanwu. 2021. “重温1990《渴望》:苦得“刘慧芳”希望被导演写“死” [Revisiting 1990’s Yearnings: The Suffering Liu Huifang Hoped to Be Written Off by the Director]. Zhuge Dushu Wu (诸葛读书屋), January 22. https://wapbaike.baidu.com/tashuo/browse/content?id=b699ee532cf79f862bfa14ad.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

The Wong Kar-wai Scandal Explained: The Dark Side of ‘Blossoms Shanghai’

From Schadenfreude to Sympathy: Chinese Online Reactions to Charlie Kirk Shooting

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

China’s “Post Parade Afterglow”: 6 Social Media Trends

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral5 months ago

China Memes & Viral5 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight7 months ago

China Insight7 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Memes & Viral11 months ago

China Memes & Viral11 months agoOur Picks: Top 10 Chinese Buzzwords and Phrases of 2024 Explained

-

China Digital11 months ago

China Digital11 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

David

June 4, 2019 at 7:21 pm

Thanks for sharing Gabi! was a very interesting read to see how the scams have been evolving haha. Perhaps to share one shared by the community at https://travelscams.org/asia/china/ a new one that is reported is the QR code scam. In essence it is similar to the “catching red envelopes” scam but done differently.

For this version, criminals paste their own QR code over the original ones by merchants (shops, bicycle sharing, etc). It is pretty much impossible to detect with the naked eye and in Guangdong alone, an estimated US$13 million was lost this way.