Featured

Weibo Watch: Frogs in Wells

Taiwan elections discussions remained relatively muted on Weibo, with limited hashtags and controlled narratives. Read more about what’s trending, from Harbin to Xinjiang, in this 22nd edition of Weibo Watch.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #22

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Frogs in wells

◼︎ 2. What’s Been Trending – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What More to Know – Five bit-sized trends

◼︎ 4. What’s the Drama – Top TV to watch

◼︎ 5. What Lies Behind – Xinjiang as copy cat

◼︎ 6. What’s Noteworthy – Balloons up in the air

◼︎ 7. What’s Popular – Jia Ling’s back in the spotlight

◼︎ 8. What’s Memorable – Gu, the controversial snow princess

◼︎ 9. Weibo Word of the Week – “Southern Little Potatoes”

Dear Reader,

While the Taiwan elections have been making headlines in international media for the past two weeks, discussions about the topic haven’t been as buzzing on Chinese social media.

As voters across Taiwan headed to the polls to elect a new president, the world watched closely as the three-way race between Kuomintang’s Hou Yu-ih, Taiwan People’s Party’s Ko Wen-je, and Lai Ching-te of the Democratic Progressive Party unfolded. Meanwhile, Weibo’s trending topic lists were predominantly filled with entertainment and travel news.

In the hours following the news that Lai Ching-te (赖清德) was elected to be Taiwan’s president, you could almost hear the crickets on the social media platform, where the only news accounts posting about the election’s outcome on Saturday evening were the Russian state-owned Ruptly and RT. Hashtags that had been active earlier in the day suddenly disappeared during the night, including the “Taiwan elections” (#台湾选举#) hashtag, and new ones like “Lai Ching-te wins the 2024 Taiwan regional leadership election” (#赖清德赢得2024年台湾地区领导人选举#).

Since the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) came to power in 2016, Chinese official media have described the ruling party as collaborating with “external forces” to seek independence and pursuing policies hostile to the mainland. Lai Ching-te, also known as William Lai, has stated that he is determined to safeguard Taiwan from threats and intimidation from Beijing and to maintain the cross-strait status quo.

“We can only wait for the mainland media to announce the results,” one prominent Taiwan-focused blogging account remarked on Saturday night, awaiting Chinese state media to come up with the ‘correct’ headlines and hashtags needed to facilitate further discussions on the platform.

By 22:45 Beijing time, about three hours after the election results made international headlines, Chinese official media channels such as Xinhua and Global Times finally reported about Lai’s win, citing spokesperson Chen Binhua of the Taiwan Affairs Office. He stated that the DPP win does not represent the Taiwanese mainstream; that Taiwan is a part of China; and that the island’s future reunification with the motherland will not be affected. Comment sections were switched off.

Some bloggers wondered why Weibo had seemingly blocked the election results from the hot search lists and why the topic was so controlled. After all, they said, isn’t this just about “the new governor of Taiwan province”? Some commenters jumped on other popular hashtags, mainly related to the super popular ‘Weibo Night’ event, to express views on the elections or how underreported they were. Weibo commenters also used phrases such as “poison frogs,” “Tai[wan] frogs,” or “the frog village has elected its new chief” to discuss the election results.

On Chinese social media, people from Taiwan are often referred to as frogs, inevitably leading to other frog-related phrases to talk about the island. The ‘Taiwan frog’ meme, which has become especially widespread during Tsai’s rule, is a reference to the well-known fable by philosopher Zhuangzi about a frog in a well who does not believe it when a turtle tells him that the world is bigger than the view from the well. The frog stubbornly denies the existence of the wider world and asserts that nothing lies beyond what he can see. The idiom ‘frog in the well’ (井底之蛙 jǐngdǐzhīwā) thus refers to people who are narrow-minded and who have a limited outlook on their life and surroundings.

The frog meme is used to describe Taiwanese who are thought to be confined to their island’s perspective and unable to see beyond it. It’s a play on words, as Tai-wan 台湾 and Tai-wa 台蛙 (= Tai-frog) sound similar. Mainlanders started calling Taiwanese ‘little frogs’ (蛙蛙) when they encountered Taiwanese commentators talking about the mainland as if it were underdeveloped and backward, seemingly unaware of China’s rapid progress over the past decades. A notable example is a Taiwanese TV host who, years ago, claimed that people in China couldn’t even afford boiled tea eggs and packaged pickled vegetables, sparking many jokes on Chinese social media.

Of course, there is some irony in Chinese netizens referring to Taiwanese as if they’re stuck in a well when Chinese narratives about Taiwan are so controlled and are mostly focused on cross-strait relations alone. On Sunday morning, the election result finally showed up in Weibo’s top trending lists with the hashtag “Taiwan is part of China, this basic fact won’t change” (#台湾是中国一部分的基本事实不会改变#). The hashtag had received over 260 million views by afternoon. Its main post by CCTV accumulated over 6329 replies. However, only 17 of them were visible, each and every single one reaffirming: “There is only one China.”

In this social media age, both in China and globally, it’s all too easy to find ourselves in echo chambers and filter bubbles, where we’re exposed only to voices that echo our existing beliefs — aren’t we all ‘frogs in the well’ at some point? Observing discussions about Taiwan on Western social media platforms, most commenters tend to narrow their focus to the elections, framing them as purely geopolitical. This perspective can create the impression that Taiwanese voters only express views that can be labeled as ‘pro-US,’ ‘anti-mainland,’ or ‘pro-China.’

“It’s not war with China that Taiwan’s young voters worry about, it’s jobs, housing, wages,” BBC’s Tessa Wong posted on X, where political scientist Sheena Chestnut Greitens added: “Important reminder: outside observers view Taiwan’s election primarily through the lens of geopolitical tensions and the threat of conflict, but many Taiwan voters also prioritize more bread-and-butter issues.”

Not everything is about great power struggles; not everything is about China vs the US; and not everything is a competition. This reminds me of something else I’d like to briefly share with you here. When The Guardian reached out to me a few weeks ago and asked if there was a topic I found particularly noteworthy in 2023 when it comes to China’s online environment, I immediately knew I wanted to write about the exploding popularity of ChatGPT, which also became a major topic of discussion across Chinese social media channels at that time: why was ChatGPT not “made in China”? You can read my debut piece for The Guardian, “In the Race for AI Supremacy, China and the US Are Traveling on Entirely Different Tracks,” through this link here.

Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang contributed to this Weibo Watch newsletter, which I hope you find useful.

Best,

Manya

(PS You can also find me on Instagram and Threads nowadays but I’m still most active on X here.)

What’s Been Trending

1: A Snowball Effect | Harbin has been trending every 👏 single 👏 day 👏 on Chinese social media over the past two weeks. The hype surrounding the city and its Snow and Ice Festival is similar to the buzz surrounding Shandong’s Zibo in 2023, and it shows that Chinese tourism boards are seriously stepping up their game in the post-Covid travel era. But although the Harbin hype is the result of a well-coordinated marketing campaign that has been in the making for a year, there is also that special something, the organic buzz, that has snowballed the city’s success this season ✨ . Read all about it here 👇🏼

2: Show-Inspired Journeys | The Chinese TV series Meet Yourself has significantly boosted the popularity of Dali in Yunnan. The series’ success, coupled with the official funding behind it, not only underscores the impactful role of Chinese television dramas in tourism but also illustrates how Chinese travel destination promotional strategies are being reshaped in a competitive post-Covid era.

3: From Avant-Garde Writer to Scruffy Pup | On Chinese social media, Yu Hua has transcended his status as one of China’s most renowned contemporary writers. Surrounded by memes, online jokes, and fans born after 2000, he has emerged as a cultural icon for China’s younger generations. His rise as an online celebrity highlights that Chinese youth value relatability and likability over literary prestige.

What More to Know

Besides the bigger international news topics such as the Taiwan elections, Japan earthquake, Middle East crisis, or the Epstein list, these bite-sized topics also went trending on Chinese social media 👇

◼︎ 🌟 Weibo Night | As every year, Weibo Night, unsurprisingly, managed to become the no 1 entertainment topic of the week. It is the much-anticipated live-broadcasted ceremony that looks back on Sina Weibo’s hottest celebrities, entertainment productions, and happenings of the past year. Hosted by the Sina media company, the night has been a recurring event since 2003 – long before the Sina Weibo platform was launched. The night was initially known as the ‘Sina Grand Ceremony’ (新浪网络盛典) until it turned into the ‘Weibo Night’ (微博之夜) in 2010. This year’s edition took place on January 13 – check in on What’s on Weibo later for the highlights. For last year’s list of winners, check here. (Weibo Hashtag “Weibo Night” ##微博之夜##, billions of views, 970 million views on Friday alone and a staggering 7.6 billion views on Saturday!).

◼︎ 🍎 Homeless Chinese PhD graduate in NYC | The story of a Chinese academic who turned from a “genius student” in physics at Fudan University to a homeless man in the US has gone viral recently. The man named Sun (孙) first attracted attention due a Chinese vlogger spotting him sleeping on the streets in New York. After graduating, doing his PhD in the US and obtaining a green card, the man dealt with mental issues and started wandering the streets for 16 years. With help coming from all directions, the 54-year-old Sun is now off the streets and will possibly get help in returning to his family in China (Weibo hashtag “Homeless Fudan Doctor Gets In Touch with Hometown” ##复旦流浪博士已与家乡取得联系##, 180 million views; “Family Members Already Know Fudan Doctor Who Stayed in US Is Wandering NY Streets” #家属已知复旦留美博士流浪纽约街头#, 290 million views).

◼︎ 💍 One-third of 30-Something Urbanites Are Single | Some remarkable social trends found in China’s 2023 Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook (中国人口和就业统计年鉴2023) have recently triggered online discussions. According to the statistics, the unmarried rate among the 30-year-old population in China’s urban areas now exceeds 30%. Experts explain that this is mostly related to Chinese younger generations postponing marriage due to spending longer time in education and also because of the relatively high cost of living. At the same time, China’s rural areas have also seen a staggering decrease in marriage rates (in 25-29 age group over 47% is unmarried), which can mostly be explained due to a gender imbalance in marriageable age groups. (Weibo hashtags “30% of 30-Somethings in Chinese Cities are Single” #全国城市30岁人群未婚率超30%#, 27+ million views; “Late Marriage Trend Has Spread from Cities to Villages” #晚婚已从城市蔓延到农村#, hashtag page taken offline).

◼︎ 🍣 Fukushima Food Poisoning | Lots of Japan news went trending on Chinese social media this month, from the devastating earthquake along Japan’s western coast to the Japan Airlines jet collision. Smaller Japan news that went trending this week is a collective food poisoning incident that took place in Fukushima earlier this month. Among many guests who stayed and dined at a local Fukushima hotel, 101 people fell ill after eating raw fish. Last year, Japan also saw several other large-scale food poisoning incidents. This Fukushima incident especially went trending on Chinese social media within the context of the release of treated radioactive water from the ruined Fukushima nuclear plant, which became one of the biggest social media topics in 2023. Although unrelated, netizens link the food poisoning incident to the dangers of radioactive water (Weibo hashtag “100 people in Japan’s Fukushima Get Food Poisoning from Eating Raw Fish” ##日本福岛百人因吃生鱼片食物中毒##, 160 million views).

◼︎ 🐼 Yaya’s Weight Gain | Panda Yaya became one of the most discussed pandas of 2023. This female panda resided in the Memphis Zoo in the United States for most of her life and attracted significant attention on Chinese social media platforms after netizens expressed concern about her seemingly thin and unhealthy appearance. When the beloved panda finally returned to Beijing after two decades, her arrival became a true social media spectacle. Now, living in the Beijing Zoo, Yaya is often spotted enjoying her bamboo dinners and she clearly gained a lot of weight, much to the delight of netizens who see this as a sign that the panda is doing much better in China than in the US. (Weibo hashtag “Yaya Became A-Letter Chubby Panda”” ##丫丫胖成了A字熊##, 120 million views).

What’s the Drama

We’re introducing this new short Weibo Watch segment to keep you in the loop about some of the most-discussed TV dramas and series in China, as they’re a significant part of China’s online environment. While the South Korean TV drama Death’s Game (#死期将至#), of which Part 2 was released on Jan 5, has been popular on Chinese social media recently, it’s Wong Kar-wai’s Blossoms Shanghai (繁花) that is among the top trending Chinese TV dramas at the moment. The series first started airing on CCTV-8 and Tencent Video on December 27.

Adapted from Jin Yucheng’s award-winning novel, Blossoms Shanghai is set in 1990s Shanghai and tells the story of the young man A Bao (played by the ‘Weibo King’ Hu Ge 胡歌) who aims to become a successful businessman and self-made millionaire during China’s booming economic reform period. The series portrays a sharp contrast between the man’s troubled past and the city’s vibrant present. Noteworthy:

▶️ This is the first TV drama produced by Hong Kong film director Wong Kar-Wai, internationally acclaimed for movies such as Chungking Express and In the Mood for Love.

▶️ Particularly noteworthy is the inclusion of the now 91-year-old renowned Chinese actor You Benchang (游本昌), famous for his iconic role as the legendary monk Ji Gong in the 1980s. Despite his age, the actor spent entire days on set with his much younger colleagues, enduring ten-hour working days.

▶️ Due to the success of the series, locations featured in it are experiencing an influx of visitors, especially Shanghai’s Huanghe Road (黄河路). Shanghai’s Fairmont Peace Hotel on Nanjing East Road, also featured in Blossoms Shanghai, has even introduced a new menu featuring various dishes that also come up in the series.

An international/subtitled online release is expected soon, but if you’re in China, you can watch via Tencent here.

What Lies Behind

Similar to Zibo in 2023, it’s the city of Harbin that has successfully generated a significant social media buzz this season, attracting hordes of winter tourists. On the other side of Northern China, Xinjiang Province is also eager to step into the spotlight.

While the Harbin International Ice and Snow Festival celebrated its official opening ceremony on January 5th, Xinjiang’s Ili Prefecture hosted an event to promote its first Tianma Ice and Snow Tourism Festival. The Snow Festival, scheduled to open on January 14th at Zhaosu County’s Wetland Park, will feature various winter activities and ice & snow sculpture exhibitions. By incorporating folk culture elements and highlighting its numerous ski resorts, local authorities aim to position Xinjiang as the third trending tourist destination after Zibo and Harbin.

However, the ‘online buzz’ surrounding Xinjiang hasn’t unfolded exactly as they had hoped. Local Xinjiang residents began expressing their opinions on social media, including on promotional videos on Douyin, cautioning tourists about high prices. For example, they pointed out that their popular spicy fried chicken dish (辣子鸡) could cost over 200 RMB (US$28), more than double the price elsewhere in China. A well-known Xinjiang vlogger suggested that budget-conscious tourists might find visiting the region in the summer more economical, while others criticized Xinjiang for the overcharging of tourists. Following the flood of online comments, the Xinjiang Culture and Tourism Department (新疆文旅) closed several Douyin comment sections.

Xinjiang’s efforts to go viral as a tourist destination show that it takes more than official propaganda to create a buzz – people are looking for genuineness, value, and that one special thing that makes it all worthwhile. During the summer of 2023, Xinjiang actually had an initial strong moment of domestic tourism recovery. After the pandemic years and strict zero Covid policies, many Chinese travelers were eager to experience something new and prioritized unique locations over a low budget. Now that the initial travel craze phase has passed, travelers are back to focusing on getting value for money and won’t accept being overcharged.

One definite upside of this marketing fail is that Chinese netizens very much appreciate how local Xinjiang residents gave travelers the heads up about the status quo. One commenter said, “After reading all the comments, I find Xinjiangers are so honest and lovely; this made me want to go visit! Maybe next time, they [local authorities] should promote their people instead.”

What’s Noteworthy

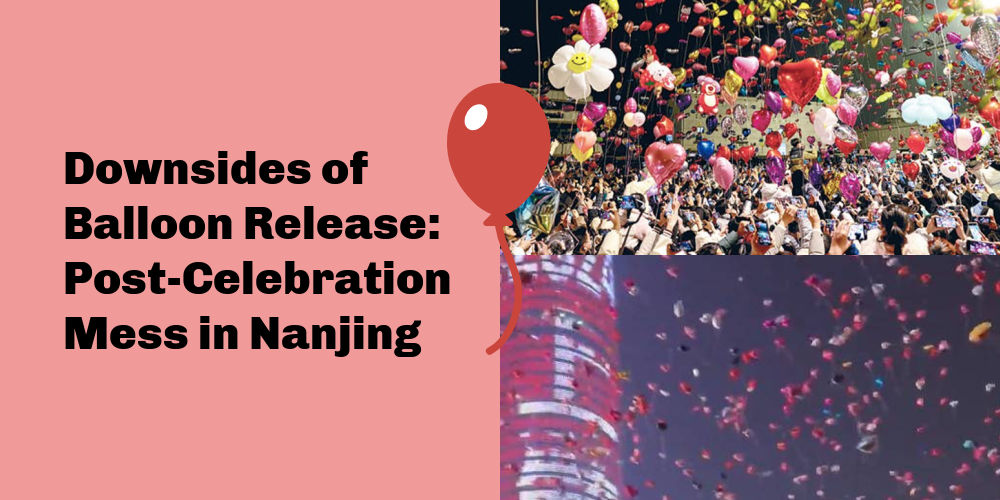

Tens of thousands of balloons were released into the sky during New Year’s Eve in Nanjing’s city center. While the scene created a spectacular count-down moment that went viral on social media, the aftermath wasn’t so pretty. In the week after the celebration, numerous balloons littered Nanjing’s commercial district — caught in trees, entangled in bushes, and even stuck on traffic lights.

To clean up this post-celebration mess, a local landscaping company was mobilized, with hundred workers utilizing multiple aerial work platforms and working around the clock for seven days to clear the Nanjing streets of the lingering balloons.

But the impact went well beyond Nanjing’s city center. Days after the event, balloons that were released in Nanjing were found as far as Hangzhou (#在杭州发现南京跨年夜气球#). Beyond the environmental impact and the extensive cleanup efforts, the use of hydrogen balloons also poses safety risks.

Hydrogen is highly flammable, and balloon encounters with high-voltage lines or open flames can result in explosions and significant damage. This actually also happened this New Year’s, creating hazardous situations for the crowds standing below the small, local explosions in the air (#跨年夜集体放飞气球引爆响#) – this is something that Chinese fire departments have also been warning about through online channels.

Nanjing is just one of the cities where thousands of balloons were released for New Year’s Eve; there were also major balloon release events in cities such as Chongqing, Chengdu, Xi’an, and Wuhan. On Weibo, numerous users have been vocal about highlighting the downsides and negative impact of these kinds of balloon releasing events.

What’s Popular

The Spring Festival holiday is known for its peak box office performances in China, with audiences eagerly anticipating the films released during this period. Last Lunar New Year, blockbuster hits like Wandering Earth II, Full River Red, and Hidden Blade made waves. This year, there’s considerable buzz around YOLO (热辣滚烫), the latest film from Chinese comedian and director Jia Ling.

Recently, Jia Ling emerged back into the spotlight after a year-long break from the public eye. On Weibo, the acclaimed actress shared that during this year, she directed her second film while also portraying the lead character. In this role, she plays a woman who drastically changes her life after being withdrawn from social life and who takes up boxing, for which Jia Ling shed approximately 100 pounds (50 kg).

Jia Ling’s remarkable weight loss for her upcoming film quickly became a trending topic, with her Weibo announcement garnering nearly 60,000 responses in just one day. Many view this dramatic change as a testament to Jia Ling’s incredible dedication to her work. After her successful and award-winning director’s debut Hi, Mom in 2021, this upcoming film is also expected to do very well during the holiday. YOLO (热辣滚烫) is set to premiere in Chinese theaters on February 10. Read more here👇.

What’s Memorable

As we’re back in the snow season, we’ve picked this article from our archive from one year ago which explores how and why Eileen Gu, the American-born freestyle skier and gold medallist, became an absolute viral sensation in China. Gu represented China in the 2022 Beijing Olympics and received praise for her excellent halfpipe World Cup performance during the 2023 Chinese New Year.

At the same time, Gu’s success also generated many discussions about her alleged privileged status, especially within the context of her being praised as a role model for Chinese (female) younger generations. Read here 👇

Weibo Word of the Week

“Southern Little Potatoes” | Our Weibo Word of the Week is “Southern Little Potatoes” (nánfāng xiǎo tǔdòu 南方小土豆).

The term “Southern Little Potatoes” (南方小土豆) is all the rage recently in the context of the hype surrounding Harbin. This ice-and-snow tourism season has seen a huge influx of tourists from the warmer southern regions who are heading north to the snow-blanketed Harbin or other destinations in the Three Northeastern Provinces (东北三省).

The southern tourists visiting China’s cold northeast tend to stand out due to their smaller stature, light-colored down jackets, and newly-bought winter hats. Their appearance not only contrasts with that of the typically taller and darker-dressed locals, but some people also think it makes them look like little potatoes. After the term ‘southern little potato’ became popular due to a viral video, some southern tourists, especially women, also adopted this term to humorously describe themselves.

The playful term quickly caught on, and locals started using it as a humorous marketing strategy to attract more southern visitors. Harbin street sellers are now selling plush keychains of “southern little potatoes,” and even local taxis are inviting the “baby potatoes” to get on board (土豆宝宝请上车) for complimentary rides. Through jokes, memes, and media stories about these ‘potatoes,’ a narrative has been constructed about the city of Harbin taking care of and pampering these ‘naive,’ ‘little’ visitors.

Although the term is meant to be affectionate, not everyone appreciates it. As the term predominantly refers to smaller women, some critics feel that by making “Southern Little Potatoes” (南方小土豆) part of its Ice and Snow economy promotion, Harbin is actually being somewhat chauvinistic and is contributing to sexism while reinforcing stereotypical perceptions of southern women.

While some critical bloggers are arguing that the term is harmful and derogatory, the majority of netizens are still using the term for light-hearted banter about the enthusiasm of southern visitors and the hospitality of the northerners welcoming them.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

China Society

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

From 5,000 people crashing a rural pig feast in Chongqing to the collective effort to save Yanran Angel hospital.

Published

1 week agoon

January 22, 2026

🔥 China Trend Watch (1.22.26)

Part of Eye on Digital China by Manya Koetse, China Trend Watch is an overview of what’s trending and being discussed on Chinese social media. The previous newsletter was a deep dive into the Dead Yet? app phenomenon. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of Eye on Digital China. Not a day goes by these days when Trump isn’t trending. Whether it’s about Venezuela and Greenland, ICE, or his recent speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, his name keeps popping up in the hot lists.

However, there are dozens of other topics being discussed on Chinese social media that actually aren’t about the US or the shifting geopolitical landscape. From football to pig-slaughter feasts, from a Henan grandpa in Paris to the latest birth rates, there is an entire world of topics out there that’s blissfully unconnected to anything happening in Washington or Davos — with many of these discussions signaling bigger social stories unfolding in China today. Let’s dive in.

Quick Scroll

- 🐶 “Eat more dog meat,” a local Community Health Service Center in Ya’an advised in a seasonal health text, suggesting it would help people stay healthy & warm during cold weather. The message sparked controversy among dog lovers online. The center later apologized and issued a corrected version, replacing dog meat with lamb, beef, and chestnuts.

- ⚽ Chinese goalkeeper Li Hao (李昊) is the man of the moment after China’s under-23 national football team beat Vietnam (0-3) and advanced to the final of the AFC U23 Asian Cup. It marks the first time since 2004 that any Chinese men’s national team (at any level) has reached the final of a continental tournament. In the final, China will face Japan.

- 👶 China’s latest birth data for 2025 are in, showing yet another record low. The birth rate fell to 5.63 per 1,000 people, with 7.92 million babies born last year — a 17% year-on-year decline.

- 💸 An “underground” private tutoring operation in Beijing has been hit with a staggering fine of more than 67 million yuan (US$9.6 million) for offering after-school classes without official approval. It’s the highest fine so far under China’s “Double Reduction” policy, introduced in 2021 to curb private tutoring and ease academic pressure on students.

- 🕯️ He Jiaolong (贺娇龙), a Xinjiang local official who was at the forefront of Chinese officials livestreaming & promoting their regions in creative online ways, died this week after a fatal fall from a horse during work-related filming. She was 47 years old.

- 🎭 Another death that trended this week was that of renowned Chinese comedian Yang Zhenhua (杨振华, b. 1936), a crosstalk (相声) artist remembered for his classic performances and widely regarded as a cultural icon.

- 🏛️ A child abuse case that has haunted Chinese netizens for the past two years has come to a close. Xu Jinhua (许金花), the stepmother who tortured and starved her 12-year-old stepdaughter, known as “Qiqi,” to death, was executed on January 20. Xu was sentenced to death in April 2025, and her appeal was rejected last November.

What Really Stood Out This Week

1. Mass Shutdowns of Local Chinese Pig-Slaughter Feasts

Annual pig feasts are traditionally meant to be a source of community bonding and ritual exchange. But for many towns and districts, páozhūyàn (刨猪宴), traditional pig-slaughter feasts, have now become a source of concern, leading to shutdowns of local events across multiple provinces.

The story begins on January 9, when a farmer’s daughter nicknamed Daidai (呆呆) from Hezhou in Chongqing posted a lighthearted message on Douyin asking whether people could help with her family’s pig slaughter, saying her old dad would not be able to hold down the two pigs. In return, she promised to treat helpers to “pork soup and rice,” adding: “To be honest, I just want the road in front of my house to be packed with cars, even more than at a wedding. I want to finally prove myself in the village!”

Two days later, on January 11, when the pig feast took place, Daidai got more than she had asked for. Not only was the road in front of her home packed with cars — the entire village was completely blocked as over 1,000 cars and some 5,000 visitors arrived. With two pigs nowhere near enough, five pigs ended up being slaughtered. Livestreamers flooded the scene, Daidai’s name was quickly trademarked, and before she knew it, she had entered internet history — including her own Baidu page — as the girl who turned a local gathering into a national feast.

Daidai (middle) hadn’t expected her call for help with slaughtering two pigs would end up in 5000 people coming to her town.

By now, the incident has spiraled into a much bigger issue, as others in the Sichuan–Chongqing region want to replicate the viral success of Hechuan, creating chaos and sometimes unsafe situations by turning neighborhood moments into tourist activities. This has led to a series of events being canceled or shut down.

On January 14, a planned páozhūyàn, initiated by local influencer Jia Laolian (假老练) in Longquanyi District in Chengdu, had to be canceled at the last minute after thousands of people registered to attend. On January 17, an online influencer in Caijiagang Subdistrict, Chongqing, also held a free pig-slaughter feast that quickly led to potentially dangerous overcrowding. Police shut it down. Another event took place in Ziyang, where 8,000 people had registered to attend while there were only 200 parking spaces available. There were more.

The current hype surrounding these pig-slaughter events reflects a sense of urban–rural nostalgia for local traditions and human connections, but probably says more about how viral tourism in China has worked since the frenzy surrounding Zibo: at lightning speed, influencers and local tourism bureaus jump onto fast-moving trends, hoping to get their own viral moment and, quite literally, piggyback on it.

While these moments can create a moment of hype, the downsides are clear: a lack of oversight, weak crowd management, intrusion to local communities, and lives being suddenly disrupted. For now, ‘Daidai’ has gained about two million users on her social media account. She says she hopes to do “something meaningful” with her online influence and has become an organic ambassador for Hechuan. At the same time, she also wants some calm after the storm, saying:“The Zhaozhu Yan in Heichuan has concluded successfully. I hope everyone can return to their normal lives. I also hope my parents can go back to their previous life—I don’t want them dragged into the internet world.”

2. How a Hospital Crisis Won China’s Trust

Usually, when news emerges about Chinese celebrities facing debts or court papers, it signals a serious blow to their reputation. But in a case that trended over the past week involving Chinese actor/businessman Li Yapeng (李亚鹏) and singer/pop icon Faye Wong (Wang Fei 王菲), the opposite is true.

Li and Wong were previously married and are parents to a daughter born with a cleft lip and palate. Their experiences in getting treatment and surgery for their daughter led them to become deeply involved with the efforts to help other children. In 2006, they founded the Yanran Angel Foundation (嫣然天使基金). A few years later, they established the Yanran Angel Children’s Hospital (嫣然天使儿童医院), China’s first privately-operated non-profit children’s hospital, providing surgeries, orthodontics, speech therapy, and other support to thousands of children—many of them at no cost for underprivileged families.

For the first ten years that Li and his team leased the hospital location, the landlord provided them with heavily discounted rent as a sign of his goodwill. In 2019, that agreement ended, and the rent doubled to market value at 11 million yuan per year (over US$1.5 million). But then Covid hit, and while the hospital still had all of its staffing and lease costs, surgeries were postponed.

On January 14 this year, Li Yapeng posted a lengthy video on his Douyin account titled “The Final Confrontation” (最后的面对), in which he explains how they fell behind on their rent since 2022, now finding themselves in a debt of 26 million yuan (over US$1.5 million) and facing a court judgement that leaves them with little choice but to vacate the premises and shut the hospital down.

Something that struck a chord with netizens is how Li, who bears joint liability for the unpaid rent, made no excuses and openly acknowledged his legal obligations, while at the same time emphasizing his personal sense of responsibility to ensure that children waiting for surgery would still receive the help that had been promised to them.

Public perception of Li Yapeng, who was previously seen as a failed businessman, transformed overnight. He was suddenly hailed as a hero who had quietly devoted himself to charity all this time, while accumulating personal debts.

Donations started flooding in. Within two days, over 180,000 people had donated a total of 9 million yuan (US$1.3 million), and by January 19 this had grown to more than 310,000 people supporting the hospital with nearly 20 million yuan (US$2.8 million). Beyond direct donations, netizens also supported Li Yapeng by tuning into his e-commerce livestreams. One businessman from Jiangsu even offered 30,000 square meters of free space for the hospital to relocate.

Meanwhile, netizens began wondering why Faye Wong, Li’s ex-wife with whom he had founded the foundation and hospital, was staying quiet. Just as some started to label her a diva who no longer cared about the cause, a 2023 audit report revealed that since divorcing Li Yapeng in 2013, she had been anonymously donating to the fund every year for a decade, totaling more than 32.6 million yuan (US$4.6 million) to cover rent and staff salaries.

There are many aspects to this story that have caused it to go viral, and that make it particularly noteworthy. It is not just the turnaround in public sentiment regarding Li and Faye Wong, but also the fact that people are more willing to donate to a cause they genuinely believe in. Although Li and Wong’s foundation technically falls under the Red Cross system, that organization has faced significant criticism and public distrust in China over the years.

What also helps are the personal stories shared on social media by those who have had direct experience with the hospital, or who know people working there. These include deeply moving accounts from families who saw all their savings depleted while trying to get proper care for their three-year-old child born with a cleft lip, then traveling for days from Gansu to Beijing with little more than a sliver of hope—only to learn that their child would not only receive surgery for free, but that the hospital would also help cover temporary lodging and travel costs. Many feel that causes like this are rare, and deserve to continue.

After years of stories about celebrities evading taxes, good causes misspending money, and corruption getting mixed up with charity, this is a story that restores trust — showing that some celebrities truly care, that some charities do turn every penny into help for those in need, and that netizens can genuinely make a difference. “This is the most heartwarming news at the start of the year,” one Weibo commenter wrote.

For now, it remains unclear whether the hospital can remain at its current location, but operations continue, and negotiations are ongoing. Fundraising has been paused for the time being, as annual donation targets have already been exceeded.

3. The Sudden Death of a 32-Year-Old Programmer and the Renewed Debate Over China’s Tech Overtime Culture

The sudden death of a 32-year-old programmer who worked at a tech company in Guangzhou is sparking discussion these days, as his death is being linked to the extreme overtime work culture in China’s tech sector.

The story is attracting online attention mainly because his wife, using the nickname “Widow” (遗孀), has been documenting her grieving journey on social media, sharing stories about how she misses her late husband and the things she wishes had gone differently. He was always working late, and she often asked him to come home when he still hadn’t returned by 10:00, 11:00 p.m., or even midnight.

Gao Guanghui (高广辉) worked as a software engineer and department manager. Despite his “seriously overloaded” working schedule, his now-widowed wife describes their life together as “very happy.”

On Saturday, November 29, 2025, the day of his passing, Gao mentioned that although he was feeling unwell, he still had work matters with approaching deadlines to handle. Browser records show that he accessed the company’s internal system at least five times that morning before fainting and experiencing sudden urinary incontinence.

While preparing to go to the hospital, Gao reportedly urged his wife to bring his laptop with them so that he could finish his tasks. However, he collapsed before the two had even gotten into the car. Despite an ambulance arriving at 9:14 a.m. and efforts to save him, he passed away two hours later. He died of cardiac arrest, and hospital records note his high-pressure, long-hour work schedule.

Even in the final moments of his life, work continued to intrude. Gao was added to a work WeChat group at 10:48 a.m., while hospital staff were still attempting to resuscitate him. Hours after his death was declared, colleagues continued to send him work messages, including one at 9:09 p.m. asking him to urgently fix an issue.

Making matters worse, Gao’s widow says that in the second week after his death, his company had already processed his resignation and disposed of his belongings. The items that were sent to her were crushed and poorly packed. To this day, she says she has received no apology, no compensation, no replacement items, and none of her husband’s missing belongings.

Visuals dedicated to Gao, shared on Xiaohongshu.

On social media, people are angry. Reading about Gao’s life story — and how he was always a hard worker, sometimes working two jobs at a time — many comments indicate that it is often the most dedicated ones who get pressured the most. They see him as a victim of tech companies like CVTE that go against official guidelines and perpetuate a work culture where working overtime becomes the norm, only leading to more workload.

This is not the first time such a story has gone viral. In 2021, the death of an employee who worked at Pinduoduo triggered similar discussions about strenuous “996” schedules (working 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days per week).

Similar deaths include the 2011 case of 25-year-old PwC auditor Pan Jie, whose story went viral on Sina Weibo after doctors concluded that overwork may have played a crucial role in her death. Likewise, the at-desk death of a 24-year-old Ogilvy employee in Beijing and the 2016 death of Jin Bo, deputy editor-in-chief of one of China’s leading online forums, also prompted calls for greater public awareness of the risks of overwork — especially among young professionals.

On the Feed

“Paris Without the Filter”

“Filter-Free Paris,” or “Paris without a filter” (素颜巴黎), unexpectedly went viral after a grandpa from China’s Henan province, traveling with a senior tour group, shared his unfiltered and casual photos of rainy Paris. In an age when European travel photos are often heavily filtered and glamorized on Chinese social media, many found the grandpa’s grey, plain images of the “City of Romance” not only amusing but also refreshingly honest.

Seen Elsewhere

• A Chinese state media editorial framed the Greenland dispute as a “wake-up call” for Europe to reduce its reliance on the US. (CHINA DAILY)

• Why Western “Chinamaxxing” and “very Chinese time” memes say more about a “decay of the American dream” than about China itself. (WIRED)

• WIRED seems to be at a “very Chinese time” itself, and also launched its China issue, introducing 23 ways you’re already living in the ‘Chinese Century.’ (WIRED)

Title/Image via Wired, Andria Lo

• As Trump sows division, China says it’s the calm, dependable leader the world needs. (CNN)

• Nostalgia for the Cultural Revolution has become one of the few legally viable means of resistance, according to Shijie Wang. (CHINATALK)

That’s a wrap! Thanks for reading.

If you happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

See you next edition!

— Manya

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo. Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. If you no longer wish to receive these newsletters, or are receiving duplicate editions, you can unsubscribe at any time.

China World

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

How Chinese social media is making sense of the first geopolitical shockwaves of 2026.

Published

3 weeks agoon

January 8, 2026

2026 hasn’t exactly seen a peaceful start. In a shocking turn of geopolitical events, Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro was captured by the US on Saturday. Facing narco-terrorism charges, he was flown to New York, where he is still being held in custody alongside his wife, Cilia Flores. President Trump announced that the United States would be taking control in Venezuela, stating they are going to “get the oil flowing.”

Maduro has pleaded not guilty to the charges during an initial hearing in federal court. Meanwhile, Maduro ally Delcy Rodríguez was formally sworn in as Venezuela’s interim president, while up to 50 million barrels of oil resources are set to go to the US.

Further shaking up geopolitical tensions were Donald Trump’s comments suggesting an American takeover of Greenland, arguing that the US needs to control Greenland to ensure the security of the NATO territory in the face of rising threats from China and Russia in the Arctic.

On Chinese social media, these developments have been dominating trending lists, with “Greenland” (格陵兰岛), “military force” (武力), “Trump” (特朗普), “Venezuela” (委内瑞拉), and “Maduro” (马杜罗) among the hottest keywords across various platforms from January 6 to today.

So what is the main gist of these discussions? From official reactions to dominant interpretive frames used by Chinese commentators and bloggers, there are various angles that are highlighted the most. I’ll explore them here.

🔴 China’s Official Response: Stressing Sovereignty & Strategic Ties

Chinese officials strongly condemned the capture of the Venezuelan president. Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) stated in Beijing on Sunday that China has never accepted the idea that any country has the right to act as an “international police” or an “international judge.” The Ministry of Foreign Affairs called for Maduro’s immediate release.

Spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) described the strikes on Venezuela as “a grave violation of international law and the basic norms governing international relations,” while spokesperson Mao Ning (毛宁) condemned what she called the United States’ “long-standing and illegal sanctions” on Venezuela’s oil sector.

These statements match the broader trajectory of China–Venezuela relations.

Over the past decades, particularly since Xi Jinping’s leadership began, the relationship between the two countries has evolved from a basic economic partnership into a more strategically significant one.

During Maduro’s 2023 visit to Beijing, the two sides elevated China–Venezuela ties to a so-called “all-weather strategic partnership” (全天候战略伙伴关系), signaling close, deep, and broad bilateral relations that go beyond a general partnership, with oil cooperation as a central pillar. (In 2025 alone, Venezuela exported around 470,000 barrels per day of crude oil to China.)

Following China’s condemnation of the US actions, Venezuelan Foreign Minister Gil expressed gratitude for China’s support, underscoring their bilateral friendship.

Beyond the official response to the recent developments, there are three main frameworks within which the ‘Trump turmoil’ is discussed on Chinese social media.

🔴 Three Main Angles in China’s Online Debate

🔷 1. Major Power Politics & US Aggression

Chinese media commentators are calling Trump’s capture of Maduro a potential “major turning point” for the world. While many described the developments as a sign that “the world has gone crazy” (这个世界太疯狂了), those trying to make sense of what happened see the US move as a warning: that relatively weak countries may increasingly become playgrounds for major powers & potential targets of US aggression.

Within this reading, China is portrayed as the most stable and peaceful superpower, increasingly important in a future multipolar world order.

On the popular podcast Qiánliáng Hútòng FM (钱粮胡同), recent developments were discussed as part of America’s dominant behavior on the world stage over decades. The hosts argued that, unlike previous US leaders, Trump is far less secretive about his goals and, in this case, no longer even follows the process of seeking UN authorization or congressional approval.

Similar views appeared elsewhere, including in a trending Bilibili video by the political commentary channel Looking at America from the Inside (内部看美国), which described the Venezuela raid not as an endpoint, but as a “signal” of what is yet to come, as the US, sensing structural decline, increasingly acts reactively rather than strategically.

Zhihu author Fēng Lěng Mù Shī (枫冷慕诗), whose post rose in the platform’s popularity charts on Wednesday, also framed the moment as pivotal. While the US may once have held the upper hand, they argue, other countries now have an actual choice in which side to take in a world ruled by superpowers. They write:

💬 “If the US truly had the strength to crush everyone and dominate everything completely, it might still be able to control global affairs. But now, with the rise of China, countries bullied by the US have new choices. If you were one of them, what would you choose? To cooperate with a bandit who might kill you with an axe at any moment? Or to cooperate with a reasonable businessman who follows the rules? I believe any rational person would make the obvious choice.“1

Social media posts made with AI featuring “Know-It-All Trump” or “The King of Understanding.”

At the same time, US behavior also became a source of banter. Some netizens, from Bilibili to Xiaohongshu, posted about “The Know-It-All King” (懂王 Dǒng Wáng—a Chinese nickname for Trump reflecting his often-quoted claims to understand complex issues better than anyone) as a comical villain on a shopping spree for new territories to conquer.

Weibo post: a creative solution to the Greenland issue?

One poster offered a creative solution to the Greenland issue:

💬 “Regarding Greenland, a simple diplomatic solution would be for Barron Trump [Trump’s son, b. 2006] to marry Princess Isabella [of Denmark, b. 2007], with Greenland given to the United States as the dowry. 😁”

🔷 2. The Taiwan Parallel

Taiwan also quickly entered the discussion. In English-language media, some commentators suggested that the raid on Venezuela could smooth and accelerate Beijing’s path toward taking Taiwan.

China’s Taiwan Affairs Office firmly rejected such comparisons. Spokesperson Chen Binhua (陈斌华) emphasized that the Taiwan issue is China’s internal affair and fundamentally different from Venezuela’s situation. Many social media commenters also argued that comparing Venezuela to Taiwan makes little sense, stressing that Venezuela is a sovereign state while Taiwan is considered a province of China.

Even so, Taiwan continues to surface in discussions on Venezuela in various ways. Some users jokingly suggested that the US has now provided a “copy-paste example” of what a tactically impressive raid might look like, while others more seriously draw comparisons between the arrest of Maduro and a hypothetical arrest of Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te.

The central question in these debates, also raised by Taiwanese media commentator Hou Han-ting (侯汉廷), is this: if Lai Ching-te were captured alive in Beijing today, what right would the United States have to object? A common view in these discussions is that Trump’s actions lower the threshold for such scenarios and implicitly pave the way for China’s ‘reunification’ with Taiwan.

This reading seems to sharply contrast Washington’s own framing. In a speech on Monday, US Defense Secretary Hegseth described China as the US’s primary competitor and claimed that America is “reestablishing deterrence that’s so absolute and so unquestioned that our enemies will not dare to test us.”

On Chinese social media, however, this claim is openly questioned: does the raid on Venezuela actually deter China or Russia, or does it instead give them greater freedom of action?

💬 As political commentator Hu Xijin wrote on Weibo: “Americans might do well to ask the Taiwan authorities, and look at the global media commentaries, if the US military action in Venezuela has made the Democratic Progressive Party authorities pushing Taiwan independence feel more secure, or more anxious?”2

🔷 3. Little Europe and the Big Striped Wolf

A third major angle centers on Europe’s role. Hu Xijin has been particularly active in commenting on these developments, especially after Tuesday’s joint statement by the leaders of seven European countries pushing back against Trump’s Greenland remarks.

Hu described the moment as one of “unprecedented turmoil within the Western bloc” and, with Denmark (including Greenland) being a NATO member, as a signal of “the collapse of the so-called ‘values alliance’.”3 This idea was further strengthened by Trump’s withdrawal from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, alongside exits from 65 other organizations, which he described as “contrary to the interests of the United States.”

On Chinese social media, Europe is, on the one hand, seen as one of the weakest actors in this geopolitical episode, while at the same time being criticized as the biggest “hypocrite.”

This week’s joint statement—and Europe’s broader position—are framed as weak due to Europe’s structural dependence on the US.

Weibo commentator Zhang Jun (@买家张俊) argues that Europe leans on a “rules-based international order” which, in reality, would amount to little more than a “US-based order” should Trump succeed in taking Greenland. At the same time, the European statement lacked economic sanctions or concrete follow-up measures, amounting to little more than mere rhetoric.

💬 As one nationalistic account put it: “Europe wonders why, even after kneeling down and licking America’s shoes, it still ends up getting hit.”4

Europe is mainly criticized for being “hypocritical” for remaining largely silent on Venezuela, while forcefully defending Greenland’s sovereignty once Trump turned his attention there.

Britain, in particular, has been singled out in Chinese media narratives surrounding the developments in Venezuela. Guancha ran a piece accusing the BBC of instructing journalists not to use the word “kidnap” when describing Maduro’s capture, suggesting the broadcaster was “whitewashing” the US’s illegal actions. It also pointed to Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s response in a BBC interview, describing his comments on US actions against Venezuela as “playing tai chi” (打起了太极)—a Chinese idiom for being evasive and dodging the question.

One Weibo user (@突破那一天) noted that a Jan 5 speech by Foreign Secretary Cooper appeared to frame US actions as contextually justified, while simultaneously stressing that Greenland’s future is a matter solely for Greenlanders and Danes—accusing her of applying a double standard on sovereignty and speaking out clearly only when the target is a Western ally.

Other users summed up Europe’s role as one of “deceiving others and deceiving themselves” (自欺欺人).

Another commenter suggested that Europe has been so focused on perceived threats from Russia and China while throwing itself into America’s arms, that it failed to notice the real danger. “Oh Europe, little piggy Europe,” they mocked. “You’ve let the wolf into the house.”

🔴 “You Think the US Invasion of Venezuela is None of Your Concern?”

How unexpected was the American military operation in Venezuela, really? One final aspect that trended online was how eerily familiar it all felt.

In the second book of the popular 2008 Chinese sci-fi trilogy The Three-Body Problem, author Liu Cixin (刘慈欣) described a scenario in which Venezuela, ruled by the fictional President Manuel Rey Diaz, is attacked by the US. That Venezuela storyline from the sci-fi novel has become widely discussed for its parallels to the current developments.

The Three Body Problem from 2008 featured a storyline about the US invading Venezuela.

The famous Japanese anime series Black Jack (怪医黑杰克) by Osamu Tezuka (1928–89) also went trending for featuring a fictional plot that many netizens see as strikingly similar to what happened in Venezuela.

It involves the president of the United Federation, named Kelly, citing “global justice” to justify cross-border airstrikes on the presidential residence of the small, oil-rich fictional country Republic of Aldiga, before arresting its leader, General Cruz. Some netizens noted how the blond President “Kelly” even somewhat resembles Trump.

Scenes from Black Jack (怪医黑杰克) by Osamu Tezuka

(Some commenters argued that Osamu Tezuka was not predicting the future so much as drawing on an already familiar pattern of US interventions abroad, and that the character “Kelly” was more likely modeled on Ronald Reagan.)

In Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem, there’s a classic line told by retired Beijing teacher Yang Jinwen to former construction worker Zhang Yuanchao, who dismisses world news as “irrelevant”. In the book, Yang tells him:

📖 “Every major national and international issue, every major national policy, and every UN resolution is connected to your life, through both direct and indirect channels. You think the US invasion of Venezuela is none of your concern? I say it has more than a penny’s worth of lasting implications for your pension.”5

In the current situation, some netizens think that the quote needs to be rewritten. In 2026, it would be:

💬“Do you really think the US arresting Venezuela’s president Maduro, conflicts in the Middle East, tensions across the Taiwan Strait, or Europe’s energy crisis are none of your concern? Don’t be naive. They drive up electricity bills, food prices, and mortgage rates. In the end, what gets drained is both your wallet and your future retirement security.”

It’s clear that many people are, in fact, deeply concerned about these geopolitical developments. As some have noted, science fiction is not always about distant futures. Sometimes, it turns out, we are already living in them.

In Liu Cixin’s version of the story, ‘Rey Diaz’ drives the Americans away through a united fight of the people, breaking the streak of victories by major powers over developing countries and turning the Venezuelan president into a hero of his time.

This story, I suspect, is going to end very differently. For now, it is still being written.🔚

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 “如果说美国人有实力碾压一切,彻底的一家独大,那或许他还可以继续操控世界的局势,但如今随着咱们的崛起,全世界被美国欺凌的国家就有了新的选择,假如你是他们,你会做出什么样的决定? 是和一个随时会砍死你的强盗合作?还是和一个讲道理讲规则的生意人合作?我觉得所有的正常人都会做出合理的判断.”

2 “美国人最好问一问台湾当局,也看一看世界媒体的评论:美军在委内瑞拉的行动究竟让推动“台独”的民进党当局更加安心了,还是更加惶恐不安了?”

3 “欧洲7国领导人和丹麦领导人共同发表声明,反对美国吞并格陵兰岛,这标志着西方集团前所未有的内乱以及 它们的所谓”价值同盟”面临崩溃.”

4 “欧洲:我都跪下舔美国鞋子了、你为什么还要打我.”

5 “我告诉你老张,所有的国家和世界大事,国家的每一项重大决策,联合国的每一项决议,都会通过各种直接或间接的渠道和你的生活发生关系。你以为美国入侵委内瑞拉与你没关系?我告诉你,这事儿对你退休金的长远影响可不止半分钱”

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Eye on Digital China/What’s on Weibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump and Takaichi: The Unexpected Love Affair

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment7 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West