Digital Life in China

15 Years of Weibo: The Evolution of China’s Social Media Giant

From ‘Chinese Twitter’ to digital dinosaur, the story of Weibo reflects the shifting dynamics of China’s online media landscape.

Published

1 year agoon

WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: “15 YEARS OF WEIBO”

Weibo has turned fifteen. As one of China’s most popular social media platforms, its journey over the past decade and a half not only tells the story of Weibo as a platform but also reflects the transformations of China’s internet at large.

It was August 14, 2009, when a new Chinese social media platform was first launched. Its name was Sina Weibo (新浪微博): ‘Sina’ because it is owned and created by Sina Corporation, a Chinese online media company founded in 1998. ‘Weibo’ because the platform allows users to post short ‘blogs,’ with wēibó (微博) literally meaning micro-blog.

At the time of its launch, Sina Weibo faced little competition and quickly gained traction. Within four months, it surpassed 5 million users. Now, over 15 years later, Weibo has over 580 million monthly active users (Ke 2024; Liang 2022).

As one of the pioneering platforms in China’s social media landscape that managed to stick around for so long, its story has become an important part of China’s internet history. Its rise, transformation, and future is closely connected to the broader evolution of Chinese online developments.

Here, we’ll dive deeper into the shifting role of Weibo in China’s digital age and how its struggles mirror those of a rapidly evolving internet ecosystem, where competition, censorship, and user expectations continuously reshape the platform’s journey.

But before diving into its evolution, let’s take a step back to where it all began: the year 2009.

Outline:

1. China’s Pre-Weibo Social Landscape

2. Weibo’s Recipe for Success

3. From Grassroots Voices to Government Control

4. Navigating the Next Digital Era

China’s Pre-Weibo Social Landscape

The year 2009 was a pivotal moment of change for China’s social media and internet landcape at large. It was the year when many platforms made their exit, when Weibo was launched, and when the beginning of China’s mobile internet era forced companies to rethink their strategies (Xu 2009).

The decade preceding 2009 had been a flourishing one in which the foundations of China’s own internet ecosystem had been solidified. By 1999, nearly all of China’s future internet giants—Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, NetEase, Ctrip, Shanda, JD.com, Sina, and Sohu—had been founded, and blogging had grown so popular that 2005 became known as the ‘year of Chinese blogging’ (Mao 2020; Yu 2007, 424).

With a lively internet cafe culture, thriving online games and active message boards, those early years of social media in China were exciting, fun. Many people undoubtedly look back on them with great nostalgia.

A Chongqing internet cafe in 2005, via Baike/Baidu.

Were these the golden years of Chinese internet? For some of China’s very first online influencers, they certainly were: in 2003, Muzimei (Mùzǐ Měi 木子美), a Cantonese sex columnist who started publishing a frank web diary of her sexual encounters with numerous men, became super famous for a while. A year later, Sister Lotus (Fúróng Jiějiě 芙蓉姐姐) from Shaanxi became the next DIY celebrity, acquiring her fame for sharing personal stories and posting provocative pictures on Tsinghua message boards. With his critical and outspoken blog posts, writer Han Han (韩寒) became China’s most famous blogger and arguably was the first KOL (Key Opinion Leader) in the Chinese digital sphere (Harwit 2014, 1066; Jeffreys & Edwards 2010, 11).

In this booming blogging time, China’s early social media environment was relatively crowded. Inspired by the success of Facebook, launched in 2004, and Twitter, which debuted in 2006, many Chinese companies tried to copy their formula. By 2007, a series of Chinese equivalents emerged, including the country’s first ‘weibo’ (microblogging) platform, Fanfou (饭否). This was soon followed by competitors such as Jiwai (叽歪), Taotao (滔滔), and other domestic players, creating strong competition for Facebook and Twitter, both of which were still accessible in mainland China at the time.

Then came 2009, a politically charged year on multiple fronts—internationally, domestically, and locally.

➡️ It was the year social media emerged as a powerful tool for activism, fueling various pro-democracy protests abroad, such as the Iranian Green Movement. Dubbed “Twitter Revolutions,” these movements relied heavily on social media for sharing information and organizing resistance. This undoubtedly heightened concerns among Chinese authorities about the potential for similar events in China, especially as the summer of 2009 marked the twentieth anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests (Harwit 2014, 1077; Zhang & Negro 2013, 200).

➡️ It was the year of the major fire at the Beijing Television Cultural Center, located right behind the brand-new CCTV tower designed by Rem Koolhaas. While traditional media reported on the fire cautiously, the real story emerged through witnesses on the street using Twitter and local microblogs. Some even suggested that the fire was reported in real-time on social media before the local fire station was aware. This event highlighted for authorities the immense power of social media and the growing impact of ‘citizen journalism’ (Sullivan 2012, 775).

The fire at the Beijing Television Cultural Center, 9 February 2009 (Wikimedia source)

➡️ It was also the year of continued unrest in Tibet and major riots in Xinjiang, both of which were attributed to the free flow of information on social media. These incidents led to localized internet shutdowns and tighter centralized online controls. Following the Xinjiang riots, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter were blocked in China, and popular domestic platforms like Fanfou suspended their services.

The big exit of America’s social media giants in China and the end for early domestic platforms created a window of opportunity for new, emerging players. Local businesses quickly stepped into the social media vacuum.

The first to present a viable plan was the media company Sina. Its CEO, Charles Chao (Cáo Guówěi 曹国伟), trusted by Chinese authorities, assured the government that content on their platform would be tightly regulated and that they would guide the direction of online public opinion by structuring and organizing discussions in certain ways (Stockman & Luo 2017, 199; Sullivan 2012, 775).

Consequently, while Weibo’s launch in 2009 occurred amidst political turbulence, its founding was itself a highly political event. Not only was its creation inseparable from the political climate of the time, but the platform also became a tool for influencing and controlling public opinion and discourse.

2. Weibo’s Recipe for Success

While the start of Sina Weibo is intertwined with China’s political climate, the platform is inherently commercial. As the first microblogging platform to be authorized after the 2009 crackdown, Sina Weibo had a clear advantage and stood at the beginning of a new Chinese digital era—one marked by the dominance of domestic players and the rise of the smartphone boom.

Weibo was initially modeled after Twitter in some ways. In addition to allowing users to post images and GIFs, it also had a 140-character limit for posts, focused on real-time, public conversations, utilized hashtags and trends, and implemented a “follower-following” system. This system allowed users to follow public figures or celebrities without needing to be mutual ‘friends,’ like on Facebook.

Weibo’s old layout.

These features quickly earned Weibo the label of the “Chinese version of Twitter.” With its competition out of the way, Weibo emerged at exactly the right time.

Other Weibos: Sohu Weibo, Tencent Weibo, NetEase Weibo.

Although the timing was opportune, Sina needed more than just favorable circumstances to attract a large user base, especially because other ‘Weibos’ soon followed: Tencent Weibo, Sohu Weibo, and Netease Weibo all tried to get their share of the market. With a clear strategy, Sina transformed their Weibo into something far more than a mere Twitter clone.

Strategy #1: Right Timing, Right People

One important part of the strategy employed by Sina Weibo is that, immediately after its authorization, it started to encourage movie stars, singers and famous business, sport and media celebrities to join their platform (Zhang & Negro 2013, 201).

As an online media company, Sina was already well-connected with public figures and they had previously leveraged celebrity influence to boost their Sina blogging platform in the pre-Weibo years. Just eleven months after launching, Sina Weibo had verified over 20,000 celebrities or influentials on its platform, with some top accounts, like actress Yao Chen (姚晨), boasting over two million followers (Baike 2024).

By 2011, actress Yao Chen had 10 million followers on Weibo. Image source: Steven Millward, Tech in Asia, 2011.

While Sina Weibo competitors focused more on grassroots users, this celebrity-centric approach created a snowball effect; the more influential people joined, the more others wanted to join as well.

Within three months after launch, Sina Weibo had one million users; by its eighth month, they reached 10 million; and a year later, there were over 50 million registered users (Zhang & Negro 2013, 201).

Strategy #2: Fostering Weibo Culture

From the start, Sina Weibo also chose a noteworthy approach of being very community-driven, promoting “Weibo Culture,” holding various competitons and conferences to invite talents from all over the country to share their ideas and views on the use of Weibo, holding an annual Weibo Night, and setting up its Charity Platform.

To this day, ‘Weibo Culture’ is an important part of the platform, as Weibo is sponsor and initiator of all kinds of events across entertainment, media, sports, academics, art.

Some older and newer examples include Weibo Movie night, Weibo TV & Internet Summit, Weibo dance competition, Weibo mobile photography competition, Weibo developer challenge (2011), Weibo marketing strategy competition (2018), Weibo vlog contest, and Weibo campus awards. These initiatives allow Weibo to increase its influence across various social fields, attract more users, and enhance its brand vaue and engagement.

Strategy #3: Weibo At Heart of Unfolding News Events

What stands out most about Sina Weibo’s strategy is how it positioned itself at the center of unfolding news events—not only as the key platform for users to discuss incidents but also as an active player in gathering, managing, and disseminating information during critical moments (Li 2023, 738).

One important reason for this emphasis on unfolding news is that breaking events are a “battleground for business”—a prime opportunity to boost viewing rates, attract more users, and ultimately increase revenue.

A notable example is the 2011 Wenzhou train crash, where Weibo quickly emerged as a vital source for real-time updates. Operators actively filtered and manually reviewed posts related to the crash, extracting crucial information. Passenger accounts were highlighted as key contributors, and the platform consistently delivered the latest updates to users.

Furthermore, by showcasing and contrasting different perspectives, Weibo encouraged discussions and amplified the controversies surrounding the incident, drawing significant public attention. As Weibo users shared firsthand accounts, challenged the official narrative, and demanded transparency about what had occurred and why it was being concealed, the incident solidified Weibo’s role as China’s leading social media platform for public discourse and real-time engagement during major events (Le Han 2016, 12; Li 2023, 738).

The Wenzhou train collision, images via China Youth Online.

Fudan University’s Mengying Li conducted extensive research on Sina Weibo’s operational strategies during its early years. Focusing on major incidents or Weibo’s ‘hot event operations’ (热点事件运营), she carried out 21 in-depth interviews with Weibo operators and opinion leaders. Li found that Weibo, much like a news editor at a newspaper, played a pivotal role in helping incidents go viral—a practice that continues to influence the platform’s approach today (736-738):

🔸Weibo as News Agent: Weibo recruited and spotlighted journalists and intellectuals, prominently featuring their posts to shape public narratives.

🔸Weibo as an Information Curator: Weibo operators closely monitored breaking news incidents and acted on them immediately.

🔸Weibo as Relevancy Filter: Weibo ensured that posts from IP addresses linked to where an incident took place were prioritized and created topic pages to enable centralized discussions.

🔸Weibo as Amplifier of Key Voices: Weibo operators invited those at the center of incidents (e.g., victims or witnesses) to open verified accounts, providing them with a platform to share updates directly with the public.

🔸Weibo as Content Promoter: Weibo strategically amplified its own content by identifying and boosting key posts and user contributions through its recommendation mechanisms, distributing them via multiple channels.

🔸Weibo as Diverter: By steering attention toward new content and limiting the lifespan of trending topics, Weibo ensured a dynamic flow of fresh material to sustain user engagement and interest.

By 2011, it was clear that Sina Weibo was the ‘winner’ among microblogging platforms, leaving competitors far behind. Looking back, Chinese commentators such as Michael Anti have referred to Weibo’s early years (2009–2013) as its golden era (Koetse 2014). Sina Weibo crowned its success by acquiring the weibo.com domain name in 2011, cementing its status as the definitive “Weibo.”

3. From Grassroots Voices to Government Control

From its early years, Weibo had strong appeal—not only as a celebrity-focused platform but also for companies, brands, NGOs, and regular users. As it quickly grew into one of China’s leading social media platforms, Weibo also became increasingly attractive to state and government-related actors.

Encouraging Government Engagement

The first government-run account to pop up on Weibo in 2009 was ‘“Weibo Yunnan” (微博云南), an account belonging to the Yunnan Provincial Government Information Office. The Vice Minister of the local Party Committee’s Propaganda Department, Wu Hao (伍皓), was the one to initiate the move to Weibo as a channel for local leadership to effectively communicatie with the public and address incidents. “The more transparent the information, the more likeable the government” (“信息越公开, 政府越可爱”) he said (Henan Shangbao 2009).

In 2011, Party Chief Cai Qi (蔡奇) became one of the first high-level officials to open an active Weibo account. The Party newspaper People’s Daily joined Weibo in 2012, paving the way for many more official accounts and state media outlets to follow. By the end of its first year, there were 41 government agencies and 60 public security bureaus actively using Weibo, along with 466 major news organizations that had established their own accounts (Baike 2024; Shao & Wang 2020, 47; Wei 2016).

From the beginning, Sina Weibo took an active role in shaping the leadership’s attitude toward the platform and encouraging government engagement. The company invited government departments to create accounts and provided training on managing public opinion during crises. CEO Charles Chao even delivered lectures at the Central Party School of the Communist Party and recorded video courses for government users, covering topics such as “How Weibo Could Help the Government.” These efforts paid off, with Weibo becoming a key platform for government institutions to share information: by 2014, over 130,000 Weibo accounts were official government accounts (Li 2023, 739–740; Hou 2017, 151).

New Interactions in the Digital Age

As these official accounts, celebrity accounts, and many others joined Weibo in large numbers, it became evident that the platform had evolved into a unique digital space where multiple societal layers could converge. It enabled actors from diverse sectors, who might never interact in other settings, to engage directly and publicly—facilitating a wide range of dynamic interactions. Besides interactions between celebrities and fans, this led to numerous interesting and insightful case studies throughout the years:

🔸 Celebrities vs. State Media: For example, when state media outlet CCTV reported that famous actor and director Zhang Guoli (张国立) advocated for stronger monitoring of web dramas during the plenary sessions, Zhang publicly contradicted them on Weibo, stating he hadn’t even spoken yet. This put CCTV in an awkward position, as it became clear to the public they were reporting on discussions that had not even occurred yet (read here).

🔸 Party Organizations vs. Online Regulators: In another case, a local branch of the Communist Youth League unexpectedly voiced support for China’s gay community on Weibo after online regulators listed homosexuality as an “abnormal sexual behavior” (read here).

🔸 Netizens vs. Corporations: Another noteworthy example is the Wei Zexi scandal. Wei, a 21-year-old cancer patient, died after being misled by false treatment information found on Baidu. The incident sparked widespread outrage on Weibo, exposing profit-driven malpractice in China’s healthcare market and implicating both Baidu and the Putian Medical Group (read here).

Bottom-up Movements, Top-down Regulation

From its early years to present, Weibo has always been a platform for public-driven movements, enabling users to address social injustices, create awareness on pressing issues and influence local politics.

🔹 In 2011, for example, sociologist Prof. Yu Jianrong (于建嵘) launched a Weibo campaign called “Take Photos to Rescue Child Beggars” (随手拍照解救乞讨儿童) during the Spring Festival. Over a span of just 14 days, participants from across the country contributed more than 2,500 photos and messages. With the assistance of law enforcement, the campaign successfully reunited six abducted children with their families. Among them was Peng Wenle (彭文乐), who had been kidnapped in Shenzhen in 2008; thanks to the campaign, he was finally brought home. This highlights Weibo’s role as a platform for opinion leaders to drive meaningful social impact (Chongqing Business Newspaper 2011; Zhan & Negro 2013, 203).

“Take Photos to Rescue Child Beggars” campaign. Left: one of the photos sent in by Weibo users photographing child beggars. Right: Peng reunited with his dad thanks to the campaign (Images via Chongqing Business News).

🔹 One other famous case highlighting the public-powered impact of Weibo is that of Yang Dacai (杨达才), a former Shaanxi provincial work safety bureau head. For most people, Yang was an unknown bureaucrat—until 2012, when a photograph of him smiling at the site of a tragic traffic accident that killed 36 people went viral. This image of the “Smiling Official” (微笑局长) sparked outrage on social media and quickly led to a digital investigation into his identity and background.

What followed was a striking example of China’s Human Flesh Search Engine (HFSE) in action. Internet users dug up numerous photos of Yang wearing 11 different luxury watches on various occasions, some valued at around 400,000 RMB (approximately $65,000 USD). This discovery led to Yang being nicknamed “Brother Watch” (表哥) and made him the subject of widespread public scrutiny.

Yang Dacai became a target of Weibo’s ‘Human Flesh Search Engine’ after netizens saw him smiling at the site of a traffic accident and then found he owned various luxury watches.

The online pressure eventually triggered an official investigation. Yang was sentenced to 14 years in prison for bribery and possession of assets of unclear origin, showcasing the HFSE’s ability to hold powerful figures accountable. The Yang Dacai case is an early and prominent example of the HFSE’s potential as a tool for online protest and crowdsourced monitoring in China.

While serving as a commercial entity, boosting state-society interactions, and providing a platform for diverse voices and movements, Weibo must also adhere to the various official (and at times murky) regulations of China’s digital environment. Although Weibo employs censorship strategies and follows directives from the Central Propaganda Department (Wang 2016), it still occasionally runs into trouble.

In 2017, for instance, Weibo, along with major platforms like Tencent and Baidu, was fined by Chinese regulators for hosting banned content as part of a broader crackdown on online information deemed inappropriate by the government. In 2018, Weibo was ordered to shut down its hot search and trending topic lists as a punishment for failing to manage its information flows effectively. Similar penalties followed in 2020 for “disrupting online communication order” and “spreading illegal information.” In 2021, the Cyberspace Administration of China imposed a fine of 3 million yuan (approximately $471,165 USD) on Weibo for repeatedly allowing the publication of “illegal information.”

4. Navigating the Next Digital Era

As one of China’s social media giants, Weibo’s priority is to keep its users engaged and stay relevant. At the same, it is also a priority to keep authorities content and keep discussions in check. This balancing act has led to a seesaw movement between greater freedom and increased control on the platform. During periods of tighter regulation, Weibo’s relevance has occasionally appeared to waver, only to rise again.

Weibo Loses, Weibo Wins

📉 Around 2014-2015, when Weibo’s initial wave of success had settled, there was a growing sentiment that Weibo was on its way out, especially because other social media platforms became increasingly popular. WeChat, launched in 2011, had grown into more than just a messaging app—it became a lifestyle platform. If 2009-2012 was the golden age for Weibo, then 2012-2015 was the prime time for Tencent’s WeChat.

It was also a time when Chinese social media users were seeking their own niche online communities. Some gravitated toward Xiaohongshu (now also known as Rednote), an app launched in 2013 that blended online shopping guides with a community platform. It quickly became popular, especially among female Chinese users with interests in fashion, travel, and lifestyle.

Others turned to Zhihu, China’s first major Q&A website launched in 2011, or Kuaishou, the first Chinese short-video platform also developed in 2011. Meanwhile, video streaming site Bilibili gained early popularity among fans of anime, manga, and gaming with its interactive “bullet comments” (弹幕) feature (this allows viewers to post real-time comments that appear directly on the video screen as it plays).

During this time, Weibo was adjusting to new cyberspace regulations. In 2015, the BBC reported that new rules requiring real-name authentication on the platform could drive users away (Hatton 2015). “Weibo is dead” became a popular statement. Adding to the pessimism was the nervousness among investors during Sina Weibo’s stock market listing, fueled by growing concerns about how Weibo could handle increasing competition.

2014 Twitter conversation on Weibo being dead. (Screenshots by Whatsonweibo)

📈 But in 2016, Weibo saw a major revival with the rise of online influencers and the social media celebrity economy. Among a wave of self-made celebrities emerging during this period, Papi Jiang stood out as one of the “super influencers” (超级红人). The vlogger gained widespread fame with her humorous videos addressing everyday societal issues, becoming a rising superstar on the platform and contributing to its renewed success. Other viral creators who rose to prominence on Weibo included Aikeli Li (艾克里里), Huang Wenyu (黄文煜), Wang Nima (王尼玛), and others (Xiao Yao 2024)

Papi Jiang was one of the super viral Weibo creators of 2016.

📉 Then in 2019, a year marked by the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen protests, the US-China trade war, Hong Kong protests, and rising tensions surrounding Taiwan’s future, the censorship on Weibo seemed more stringent than ever before. This inevitably led to a noticeable decline in user engagement on the platform.

A post by a Chinese blogger, suggesting that intellectual discussions on Weibo were dying, struck a chord with millions of users (read the full translated post here). The blogger argued that Weibo was “no longer a place to share news and knowledge, nor a place for open debate.” With major events unfolding that could not be openly discussed, these issues became “like an elephant in the room on Weibo” (Koetse 2019).

📈 The Covid outbreak in late 2019 and early 2020, however, put Weibo right back at the center of China’s social media arena. Much like in its early years, Weibo was actively involved in unfolding incidents, ensuring that the latest Covid updates were readily available on the site and playing a key role in connecting those seeking help with relevant government departments.

While Weibo served as an important channel for Party media to promote narratives of a united China battling the virus, it also became a space where grassroots users expressed anger over local mishandlings and social injustices. This cemented Weibo’s role as a major online news hub during the pandemic, playing an even more “crucial role in shaping public engagement and political participation” than before (Beijing Daily 2020; Li 2023, 730-731).

Reshufflings in the AI Era

After the rise of China’s major internet companies and platforms in the late 1990s to early 2000s, followed by the transition to the mobile era between 2009 and 2013, we are now witnessing a third major phase of transformation and growth in the Chinese online media landscape: the AI era.

In recent years, Bytedance and its AI-driven apps, most notably Douyin (the mainland version of TikTok) have become increasingly influential in China. Other platforms that were initially more niche, such as Bilibili or Xiaohongshu (Rednote), have also moved into the mainstream, emerging as birthplaces for online trends and memes.

Where does this leave Weibo?

Some voices argue that Weibo’s current path has become too commercial. By prioritizing intrusive ads and clickbait headlines, critics feel it has lost its “human touch,” especially as many influential bloggers and celebrities have either left the platform or stopped updating. Somewhat ironically, they suggest that platforms designed with AI integration from the start, such as Douyin, now feel more authentic to users (Xiao Yao 2024; Tech Nice 2024).

Weibo, meanwhile, is often updates its features and is integrating more AI into its platform, not just to automatically identify and filter content, but also to create trending topic lists and content feeds, or to assist users in finding and understanding information and news events. The Weibo Smart Search AI chatbot (微博智搜), for example, answers questions about hot topics and helps users create posts about them.

Maintaining a strong foothold in China’s social media sphere is not just important for Weibo as a company, it’s also essential for official channels and state media in their efforts to shape public opinion and promote Party narratives. Weibo now has over 17,000 registered media accounts reaching an audience of millions. More than a celebrity platform, Weibo is the social home of China’s newspapers: 97% of the social and current affairs topics on Weibo’s trending lists now originate from media reports (ZGJX 2024).

Weibo’s struggles reflect the shifting dynamics of the online media environment. During a media conference in October 2024, Weibo CEO Wang Gaofei (王高飞) addressed how there has been a “decentralization” in online news consumption. Rather than looking at the centralized ‘hot topics,’ social media users, especially in the post-pandemic era, increasingly turn to personalized, decentralized information feeds. Moreover, the kind of content they prefer is also more interest-driven, which is why the role of AI is so important in social media today—something which companies like Bytedance and Xiaohongshu (Rednote) understand all too well.

Adapting to changing times, Weibo’s centralized trending topic lists are becoming less important, as the platform is now offering users more personalized topics based on their interests. Wang Gaofei remains optimistic about the platform’s future, emphasizing that media integration will continue to be a cornerstone of its strategy.

A Digital Dinosaur Standing Tall

It’s not easy to survive for 15 years in an online environment that evolves so quickly. Beyond navigating the complex dynamics of official guidelines, managing censorship, keeping users engaged, and satisfying advertisers, Weibo has had to constantly rethink its strategies and adapt to the times.

Despite uncertainties about its future role in China’s social media landscape, Weibo’s impact on the history of China’s internet is undeniable. The platform’s strength lies in its ability to facilitate public opinion, foster interaction across different layers of society, and play a significant role in news discussions. It has consistently balanced official demands with grassroots movements, occasionally stirring controversy to attract attention and highlight contentious news.

Surrounded by newer apps and younger companies, Weibo might already be considered a “dinosaur” in the world of Chinese social media. But it’s a tall one—a major example for emerging players to look up to as they navigate an increasingly complex digital ecosystem.

Even after 15 years, there is still no place like Weibo. It remains relevant as a central hub for discussing both mainstream and niche news. In an increasingly fragmented social media landscape, when something big happens, China still gathers in Weibo’s “living room.” In many ways, Weibo’s best strategy for future success might just be to remain true to what it has always been.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

References

● Baidu Baike. 2024. “China’s Weibo First Year Market White Paper [中国微博元年市场白皮书].” Last modified May 22, 2022. Accessed January 14, 2025. https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E5%BE%AE%E5%8D%9A%E5%85%83%E5%B9%B4%E5%B8%82%E5%9C%BA%E7%99%BD%E7%9A%AE%E4%B9%A6/6025166.

● Beijing Daily 北京日报. 2020. “How to Seek Help on Weibo During the Pandemic: Government Departments Will Respond” [疫情期间微博求助这样发,将有政府部门对接]. February 4. Accessed January 12, 2025. https://china.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnKpc7K.

● Harwit, Eric. 2014. “The Rise and Influence of Weibo (Microblogs) in China.” Asian Survey 54 (6): 1059–1087.

● Hatton, Celia. 2015. “Is Weibo on the Way Out?” BBC News, February 24. Accessed January 15, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-china-blog-31598865.

● Henan Shangbao·Dahe Network (河南商报·大河网). 2009. “Yunnan Provincial Government Joins Weibo” [云南省政府‘戴围脖]. Chengdu Commercial Daily, November 26. Accessed January 13, 2025. https://news.sina.cn/sa/2009-11-26/detail-ikmxzfmi9474674.d.html.

● Hou, Er. 2017. “Development Report on China’s Government Affairs New Media in 2014.” In Development Report on China’s New Media, edited by Xujun Tang, Xinxun Wu, Chuxin Huang, and Ruisheng Liu, 149–163. Singapore: Social Sciences Academic Press, Springer.

● Jeffreys, Elaine, and Louise Edwards. 2010. “Celebrity/China.” In Celebrity in China, edited by Louise Edwards and Elaine Jeffreys, 1–21. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

● Jiang, Min, and Jesper Schlæger. 2014. “How Weibo Is Changing Local Governance in China.” The Diplomat, August 6. Accessed January 15, 2025. https://thediplomat.com/2014/08/how-weibo-is-changing-local-governance-in-china/.

● Liang 梁将军. 2022. “Hardcore Research on ‘Network Effects’: Why Do You Have a Better Product but Still Can’t Beat Your Competitor?” [网络效应”的硬核研究:为什么你有更好的产品,却干不过对手?]. July 1. Accessed January 14, 2025. https://www.woshipm.com/user-research/5507557.html.

● Ke Yang Weibo Releases Q2 2024 Financial Report: 583 Million MAUs, Over Half of Ad Revenue Driven by Hot Topics, Celebrity KOLs, and Performance Ads

https://finance.sina.cn/2024-08-22/detail-inckpkpk2208211.d.html?oid=3817793013587371&vt=4&cid=76729&node_id=76729

● Koetse, Manya. 2014. “Behind the Headlines: China’s Media Landscape (Liveblog).” What’s on Weibo, May 14. https://www.whatsonweibo.com/behind-the-headlines-chinas-media-landscape/.

● Koetse, Manya. 2019. “Chinese Blogger Addresses Weibo’s ‘Elephant in the Room.’” What’s on Weibo, June 10. Accessed January 16, 2025. https://www.whatsonweibo.com/chinese-blogger-addresses-weibos-elephant-in-the-room/.

● Han, Le Eileen. 2016. Micro-blogging Memories: Weibo and Collective Remembering. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

● Li, Mengying. 2023. “Promote Diligently and Censor Politely: How Sina Weibo Intervenes in Online Activism in China.” Information, Communication & Society 26 (4): 730–745.

● Mao, Lin 毛琳. 2020. “25 Years of Transformation in China’s Internet: Two Leaps, Four Waves, and a Bet on the Future” [中国互联网25年变迁:两次跃迁,四次浪潮,一次赌未来]. Woshipm (人人都是产品经理), January 3. Accessed January 12, 2025. https://www.woshipm.com/it/3282708.html.

● Shao, Peiren, and Yun Wang. 2020. “Social Media and the Changing Political Culture in China.” In China in the Era of Social Media: An Unprecedented Force for An Unprecedented Social Change, edited by Junhao Hong, 39–63. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

● Stockmann, Daniela & Ting Luo. 2015. “Which Social Media Facilitate Online Public Opinion in China?” SSRN Electronic Journal, 64 (3–4): 189–202.

● Sullivan, Jonathan. 2012. “A Tale of Two Microblogs in China.” Media, Culture & Society, 34: 773–783.

● Sullivan, Jonathan. 2014. “China’s Weibo: Is Faster Different?” New Media Society (16) 1: 24-36.

● Tech Nice (科技Nice). 2024. “Sina Weibo: The Decline of Its Glory and the Path Forward [新浪微博:辉煌不再的背后与未来之路].” Sohu.com, January 24. Accessed January 18, 2025. https://www.sohu.com/a/753942489_121769622

● Wang, Yaqiu. 2016. “The Business of Censorship: Documents Show How Weibo Filters Sensitive News in China.” Committee to Protect Journalists, March 3. Accessed January 15, 2025. https://cpj.org/2016/03/the-business-of-censorship-documents-show-how-weib/.

● Wei, Liu. 2016. “Meet Cai Qi, Long-Time Online Celeb and Beijing’s Acting Mayor.” China Daily, November 1. Accessed January 15, 2025. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-11/01/content_27241562.htm.

● Xiao Yao 小遥. 2024. “Weibo Has Long Lost Its ‘Human Touch'[(微博早就没有‘人味儿’了].” WeChat public account “Lüedacan Kao” (微信公众号“略大参考,” ID: hyzibenlun) and published on 36Kr, September 2, 2024. Accessed January 12, 2025: https://36kr.com/p/2932177595275911.

● Xu, Zhiqiang 徐志强. 2009. “VC Gold Rush: Embracing the Mobile Golden Era [VC淘金:拥抱移动黄金时代].” 21st Century Business Herald, April 23. Accessed January 12, 2025. https://finance.sina.cn/sa/2009-04-30/detail-ikkntiam4042149.d.html?from=wap.

● Yu, Haiqing. 2007. “Blogging Everyday Life in Chinese Internet Culture.” Asian Studies Review 31: 423–433.

● Zhang, Zhan, and Gianluigi Negro. 2013. “Weibo in China: Understanding Its Development Through Communication Analysis and Cultural Studies.” Politics & Culture 46 (46): 199–216.

● ZGJX (China Journalists Association Net 中国记协网). 2024. “Sina Weibo CEO Wang Gaofei: Shaping a New Framework for Mainstream Public Opinion through Weibo’s Strength [新浪微博CEO王高飞:以微博之力共塑主流舆论新格局].” China New Media Conference, October 15. Accessed January 18, 2025. http://www.zgjx.cn/2024-10/15/c_1310786675.htm.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chapter Dive

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

We’re at a very complicated time in our online lives. An explainer of “Chinamaxxing,” the “kill line,” and the platform politics behind them.

Published

3 weeks agoon

February 3, 2026

While American TikTok users find themselves in a “very Chinese time” of their lives, Chinese netizens are fixated on the American “kill line.” Beyond the apparent digital divide, both trends reflect shared anxieties and shifting power dynamics between the US and China.

In the first month of 2026, two noteworthy social-media trends, both telling of the times we live in, went viral in the US and China: a China-focused trend in the US and an America-focused one in China.

In the US, TikTok videos and Instagram posts showing young people cheerfully portraying themselves as “Chinamaxxing,” or being “in a very Chinese time” of their lives, began popping up across social media.

Meanwhile, in China, posts about the darker side of American society and its so-called “kill line” (斩杀线) dominated trending lists.

In this week’s chapter dive, I’ll explain the stories behind both of these trends and why, despite their very different implications, the dynamics driving them are strikingly similar.

Converting to “Chinese Baddies”

Over the past week, the phrase “Becoming Chinese” (成为中国人 chéngwéi Zhōngguórén) has been gaining traction on Chinese social media. On January 30, the headline “Why ‘Becoming Chinese’ Videos Are Going Viral’ even made it to the number one most popular topic on Chinese platform Toutiao (“成为中国人视频为什么火了”).

Before reaching China’s social media, the trend had been gaining momentum on TikTok and Instagram for months, with viral videos showing foreigners humorously flaunting their supposedly deep connection to China by doing things like drinking a nice cup of hot water (the solution to everything), using traditional Chinese medicine, sitting in a squatting position while smoking Chinese cigarettes and holding Tsingtao beer, eating noodles or dim sum—all while wearing that popular Adidas “Chinese jacket.”

This is all referred to as “Chinamaxxing” or “Chinesemaxxing”: optimizing life by living in a Chinese-coded way.

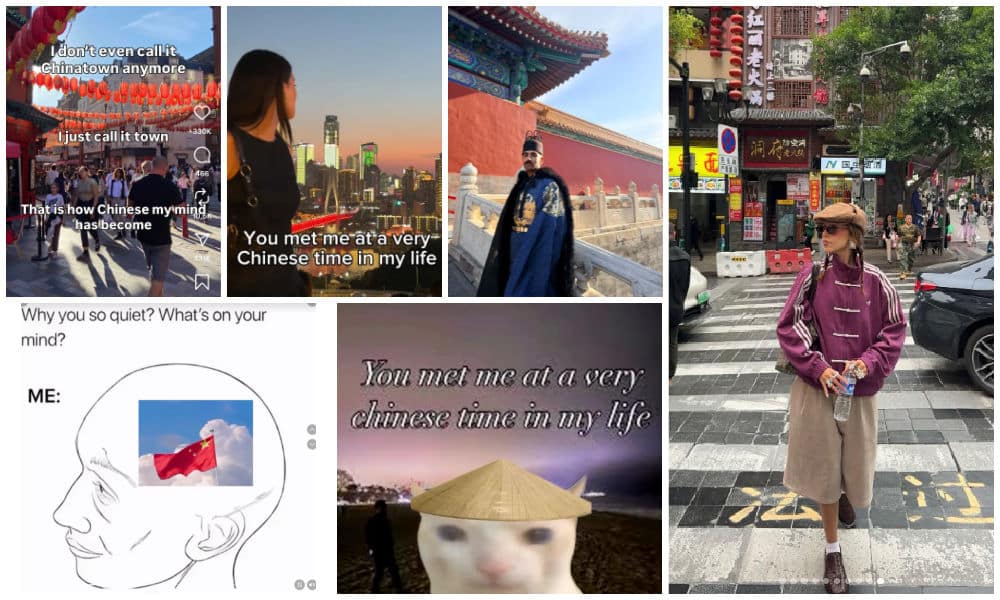

Various “very Chinese time” examples (TikTok/Instagram).

The build-up to this moment has actually been underway for several years. In the post-Covid era, China’s global pop culture influence has grown noticeably, driven both by increasingly outward-facing efforts from Chinese companies and state actors, and by a broader shift among younger audiences in the US toward Asia.

As part of this broader shift, several notable online moments have emerged over the past few years, including the viral success of a Chinese pop song in 2022; the 2024 breakout of Black Myth: Wukong; the 2025 “TikTok refugee” phenomenon; Chinese rapper SKAI ISYOURGOD becoming a staple on TikTok; and the widely watched March 2025 China tour of American YouTuber IShowSpeed, followed by a less impactful but still meaningful China visit by American influencer Hasan Piker.

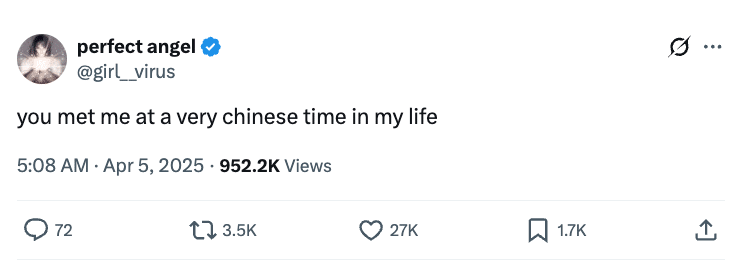

The now-famous line “You met me at a very Chinese time in my life”—inspired by the quote “You met me at a very strange time in my life” from the final scene of Fight Club—first surfaced on X in April 2025. The X account “Perfect Angel” (@girl__virus) then posted the phrase in a tweet that since has gathered over 950,000 views.1

The X post of April 5, screenshotted Jan 30, 2026.

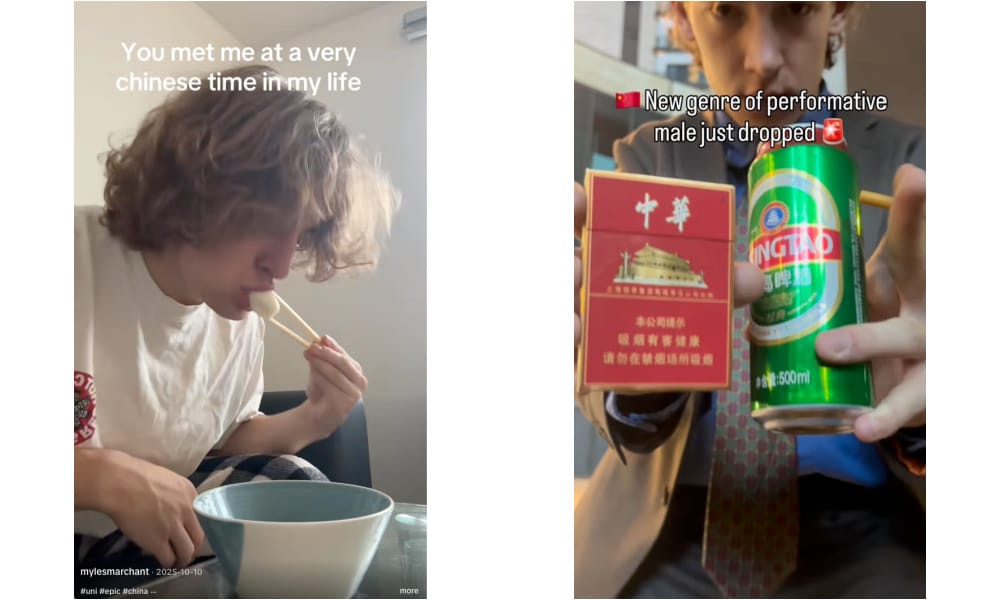

The trend snowballed from there, especially in October 2025. When creator Myles Marchant posted a video of himself eating dumplings while using the phrase, it received nearly 200k likes. Afterward, all kinds of internet users, but particularly American content creators, started using the phrase in videos to show off just how “Chinese” they were.

Myles Marchant and McMungo in their videos.

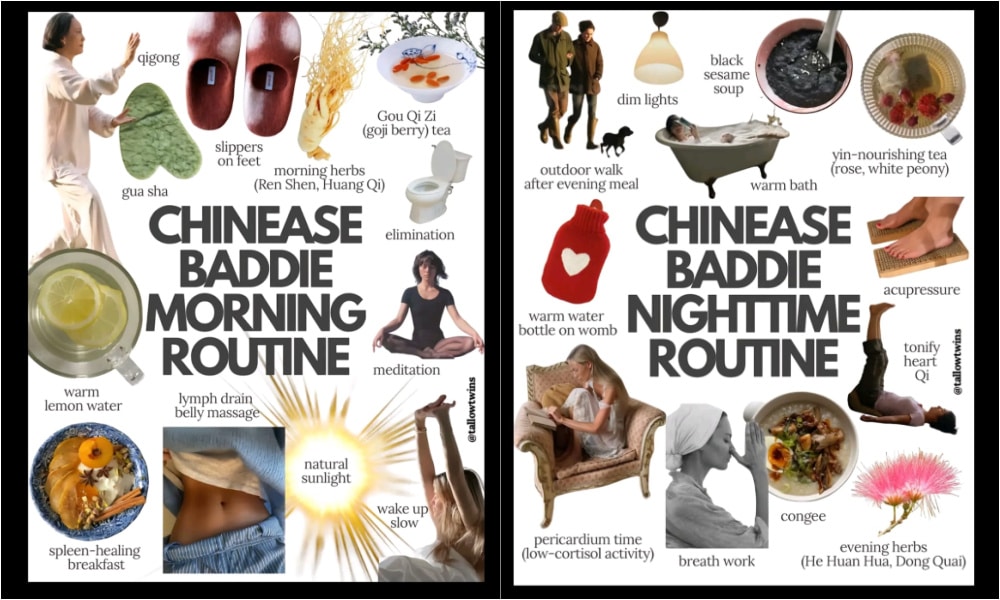

As the meme went viral, from October 2025 through January 2026, it continued to evolve. What began with cigarette smoking and playful performances of “Chinese” behavior has, for many TikTok users, grown into something more. Drawing on Chinese food philosophies and wellness practices, they now present “Becoming Chinese” as a lifestyle trend focused on better energy, health, and skincare.

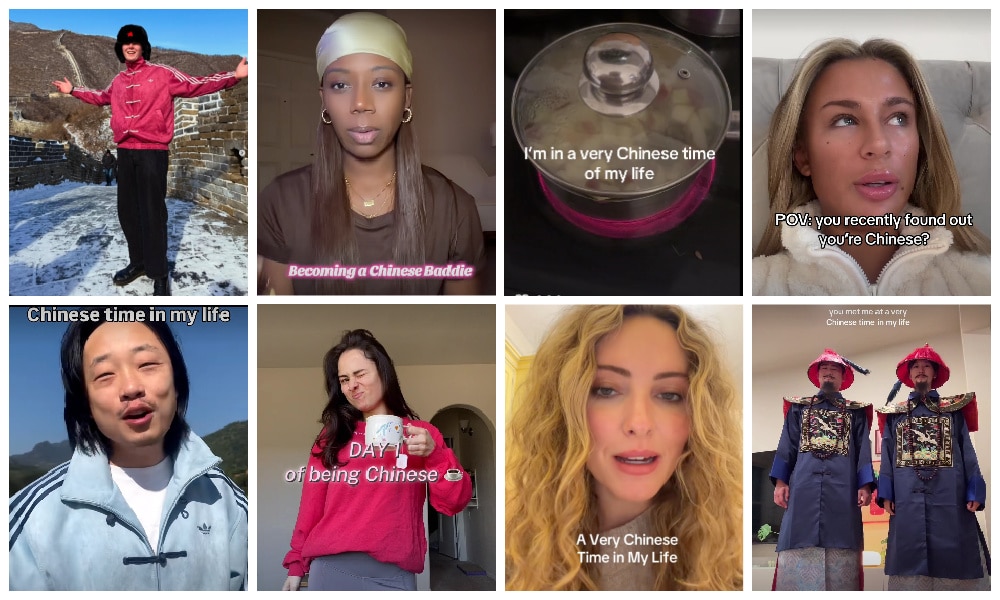

Chinamaxxing, Chinese Baddies, Becoming Chinese, A Very Chinese Time of My Life: Trends on Tiktok.

TikTok creator Missmazz, for example, introduced her morning routine “since recently converting to Chinese”: wearing slippers in the house, doing small jumps to “activate” lymph nodes, and drinking warm water and herbal tea. Creator Ohplsnatagain also shared her “first day of being Chinese,” drinking ginger tea, boiling apples, wearing red, and avoiding cold drinks.

“Chinease” morning and night routines, shared on TikTok by Tallow Twins.

Besides those aspiring to become Chinese, some Chinese creators have expressed their joy about the trend others emerged as online guides to these newly adopted identities and lifestyles. Creators like Emma Peng made a video telling people, “my culture can be your culture,” while others, like Sherry, actively encourage people to become Chinese: “It’s gonna be so fun!”

They have now formed an online community of self-labeled “Chinese baddies,” sharing recipes, morning routines, and tips for being as ‘Chinese’ as possible. On Chinese social media, netizens are humored by the overseas trend, and see it as a sign of just how powerful Chinese cultural confidence has become (“藏在烟火气里的文化自信才最有感染力”).

America’s “Kill Line”

While American social media users have been busy Chinamaxxing, Chinese social media have been feverishly discussing America’s so-called “kill line” (also translated as “execution line,” 斩杀 zhǎnshāxiàn).

The term first went trending in late 2025 after it was coined by the Northern Chinese livestreamer Squishy King (斯奎奇大王), better known by his nickname “Lao-A” (牢A), who is particularly active on Bilibili, the Chinese platform known for its strong anime and gaming subculture.

Lao-A has been livestreaming since 2024 without ever showing his face on camera. Through pure voice narration over images, he became known for casually chatting in livestreams—sometimes lasting over five hours—about a wide range of topics, especially those connected to American society. Lao-A claimed he was a Chinese biomedical student in Seattle who worked part-time as a forensic assistant, handling unclaimed bodies and preparing them for medical education or research.

Profile image of “Lao A”, who never shows his face on streams.

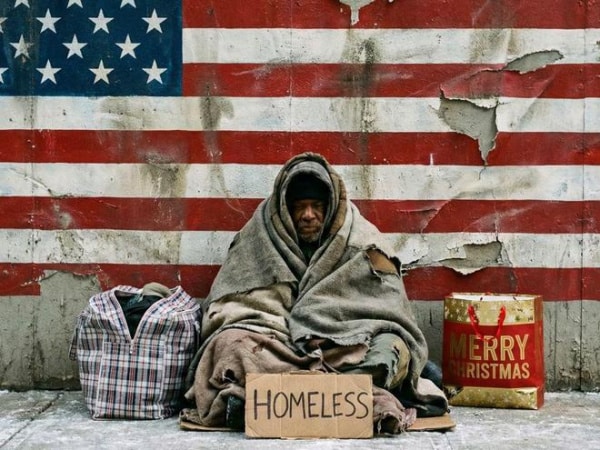

On November 1, 2025, during a stormy Halloween Friday night, Lao-A hosted another one of his five-plus-hour live-chatting streams, in which he spoke about the bad weather and homelessness in the US.

He mentioned how people living on the streets could easily die from a cold or Covid that turns into pneumonia without proper treatment, and how dreadful he felt about the freezing conditions—knowing that on Monday he would see the bodies of people who had died on the streets that very weekend.

According to Lao-A, the unidentified bodies of homeless people would be brought by the police to his school, where they could still generate some value. Drawing comparisons to “harvesting in harsh winter,” he introduced the concept of the “kill line,” borrowing the term from multiplayer/role-playing games such as Hades or League of Legends.

In gaming, a “kill line” refers to the health-point (HP) threshold below which a character can be instantly killed, with no possibility of recovery. Lao-A suggested that the situation of marginalized and homeless people during Seattle’s winter was similarly bleak: their deaths are treated as almost inevitable, even though basic medical care—such as antibiotics—might prevent them.

The way Lao-A spoke about his work and the darker sides of American society spread rapidly through Bilibili’s comment culture and then into wider Chinese social media, especially as he expanded on the topic in other livestreams, where he further discussed poverty in America, from the healthcare system to food assistance programs.

Visuals accompanying a report about Lao-A on the 163.com website.

Lao-A particularly focused on medical bills as a key component of America’s “kill line.” He described how people suffer first and then seek care, only to be further burdened by crushing costs—arguing that the American system drains people at their most vulnerable. An unexpected event such as illness, job loss, or a car breakdown can suddenly disrupt a family’s cash flow, leading to unpaid bills and a collapse in credit scores. Bad credit, in turn, makes it harder to rent housing, pass background checks, or secure affordable insurance, while debts pile up. This downward spiral, he suggested, eventually pushes people past a final execution threshold: too broke, too sick, too depressed, and too far gone to recover, ending in homelessness or addiction and shortening life spans.

Lao-A framed this as a systemic trap created by capitalism: a game mechanic in which the rules are rigged so that once someone falls below the threshold, the system itself kills them. Besides the “kill line,” he introduced other gaming-inspired terms, such as using “Gundam” (高达, after the Japanese model kits) to refer to the bodies he handled, or “slimes” (史莱姆) for decomposed bodies found in sewers.

In some ways, Lao-A’s “kill line” resembles the concept of ALICE (“Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed”), a demographic category created by the nonprofit United For ALICE to describe American households that earn above the federal poverty line but still cannot afford basic necessities such as housing, childcare, healthcare, or groceries.

By mid-December 2025, the term and the stories surrounding it had entered the mainstream and began hitting trending lists on Weibo, Toutiao, and Kuaishou.

Cartoon by Chinese state media outlet CRI Online about the killing line. Top texts say: “Thriving economy, America first, America great again.” On the staircase, it says: “Unemployment, unexpected costs, illness.”

As the “kill line” quickly entered China’s online lexicon, it was also embraced and boosted by official media. After earlier coverage, Qiushi (qstheory), the Chinese Communist Party’s most authoritative theoretical journal, published a January 4 commentary arguing that the “kill line” reflects a widespread condition in which Americans’ capacity to withstand risk has been pushed to its limits, while Trump’s MAGA movement fails to work towards a solution as it focuses on cultural identity rather than addressing the economic challenges faced by millions of Americans.

Something that also caused a stir online, is how American media began reporting on the Chinese “kill line” concept. First Newsweek on December 26, followed by The Economist and later The New York Times. The phrase even surfaced at the World Economic Forum in Davos, when a Chinese state-media reporter asked US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent about the phenomenon.

All of this placed a considerable spotlight on Lao-A himself, whose real identity and personal backstory began to be questioned by internet users. After he was identified as the possibly 30-year-old “Alex Kong 孔” from Daqing, who attended a community college in Seattle, more of his details were leaked online. Lao-A said he feared for his safety and returned to China.

This supposed “escape from America” became a major story on Chinese social media, with Lao-A repeatedly topping trending charts from January 17 onward. Attention peaked around January 22–23, after he joined Weibo and participated in joint livestreams with Chinese professor and prominent nationalist commentator Shen Yi (沈逸), and again around February 1, when he streamed with foreign-policy commentator Gao Zhikai (高志凯). During this period, Lao-A and the dystopian “kill line” narrative completely dominated Chinese online discussions.

Throughout his solo livestreams and collaborative appearances, Lao-A has continued to paint an especially dark picture of American society, describing graphic gang violence, failures in the education system, murky organ-transplant systems and black markets for organ harvesting (claiming that healthy Chinese students who have not used drugs are “very valuable”), and Chinese female students abroad as “ideal hunting targets” for white men—explicitly warning Chinese parents not to send their daughters to study overseas.

By now, “kill line” is a term that pops up all over Chinese social media and is applied to all kinds of news coming from America, from the Epstein files to the Alex Pretti shooting.

Where the “Kill Line” Meets “Chinamaxxing”

On the famous Know your Meme website, the phrase “You Met Me At A Very Chinese Time In My Life” is described as “ultimately meaningless and purposefully absurd.” But it’s actually not.

Both the “Becoming Chinese” trend and the discourse surrounding the “kill line” are shaped by our current media moment and reflect broader, shifting narratives about China, the United States, and global power.

While China’s rise has been a major media theme for years, a lot of Chinese influence had felt invisible for younger generations in the West, even if they were already living, wearing, and consuming “made in China.” More recently, however, China’s soft power narratives have become more visible, with popular culture emerging as a powerful tool.

The changing attitudes toward “made in China,” alongside a growing interest in Chinese tradition and elements of ancient culture, took shape in the late 2010s as China’s domestic cultural confidence increased. This development was partly supported by China’s flourishing livestreaming economy & homegrown e-commerce platforms, as well as more assertive official messaging around the idea of products being “proudly made in China.”

Wang Yibo poses with Anta’s “China” t-shirt in 2021, the year that “made in China” had become cool again.

Younger Chinese consumers in particular—those born after 1995 or 2000—began showing more interest in domestic brands than earlier generations. This trend reflected not just consumer preference, but a stronger identification with Chinese culture and national identity. By 2021, a Global Times survey indicated that most Chinese consumers believed Western brands could be replaced by Chinese ones (75% of respondents agreed that “national products could fully or partially replace Western products“).

By 2025, pop-culture products emerging from this renewed focus on domestically produced goods—often incorporating traditional Chinese aesthetics—began reaching audiences beyond China, finding traction in Western markets as well.

At the same time, the United States experienced significant societal divisions in the aftermath of the 2024 elections, while its global image and cultural influence were affected by the dismantling of traditional US soft power channels.

Together, these developments shaped broader changes in global public opinion, tilting toward a more favorable view of China as “the world’s leading power,” and fueling conversations about a future increasingly framed through a Chinese lens.

This wider geopolitical context forms the backdrop against which the two viral trends discussed here took shape.

–Why these trends took off

🔹 The Decay of the American Dream and Insecurities about China’s Dream

Geopolitical power shifts alone are not enough to explain the virality of both “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” discourse. Current socio-cultural dynamics also play a major role.

In both the US and China, people’s sense of security, future, and identity is shifting, and other countries are increasingly used as mirrors, escape routes, or coping mechanisms to process that change. Young working-class Americans under Trump and middle-class Chinese facing “involution” (nèijuǎn 内卷, a seemingly never-ending societal rat race) are questioning their systems, but arrive at opposite conclusions by using each other as contrasts.

🇺🇸 “A projection of what Americans believe their own country has lost”

In a recent article for Wired,”Why Everyone Is Suddenly in a ‘Very Chinese Time’ in Their Lives,” the authors argue that the “very Chinese time” meme is “not really about China or actual Chinese people,” but instead functions as a projection of what Americans believe their own country has lost.2

Rather than offering an accurate depiction of China, the trend relies on stereotyped markers of “Chineseness” to express frustration with US infrastructure erosion, political instability, polarization and, as PhD researcher Tianyu Fang puts it, “the decay of the American dream.”

In this context, China appears as an aspirational contrast—”less as a real place than an abstraction”—through which Americans critique their own realities.

🇨🇳 “Why China is suddenly obsessed with American poverty”

Similarly, in a The New York Times article titled “Why China Is Suddenly Obsessed With American Poverty,” author Li Yuan argues that the “kill line” narrative offers emotional relief to Chinese netizens while also helping to deflect criticism of domestic leadership. As she writes, “the worse things look across the Pacific (…), the more tolerable present struggles become.”3

A related conclusion is reached in an article by The Economist,4 which suggests that the surge in discussion about America’s failures says less about the realities of life in the US than about China’s own anxieties over slowing growth and the fragility of domestic political discourse.

While the “Chinese Dream,” which prioritizes collective effort and national strength, is promoted as part of state ideology, everyday life tells a more sobering story, in which climbing the social ladder seems increasingly out of reach for millions of Chinese facing economic slowdown, high youth unemployment, and a constrained space for criticism.5

Yet as narratives about the perceived failure of the “American Dream” flood Chinese social media, China itself begins to look like the better place—even with all of its own challenges.

Ultimately, both the “Becoming Chinese” and “kill line” phenomena are embedded in collective anxieties about vulnerability and decline, fueling a growing hunger for counter-narratives.

–The stories told

🔹Fantasizing about “the Other”

Those counter-narratives do not need to be realistic. To fulfill their role in channeling perspectives, insecurities, and even a sense of cathartic relief about the present and future, they can’t actually be nuanced. Simplification, exaggeration, and symbolic contrast are precisely what make them effective.

🇺🇸 “Chinese cultural identity as a disposable trend”

In the case of “Becoming Chinese,” the trend is comically fairy-tale–like, suggesting that people of all backgrounds can “turn Chinese” in the blink of an eye. One popular meme even implies that there is no need to “kiss the frog” to meet the prince: simply looking at the frog would already make you Chinese.

Beyond fairy tales, there is also a gaming logic at play in other “Becoming Chinese” memes, with different levels of “Chineseness” to unlock to reach that final mythical state of Being Chinese.

Although this is all tongue-in-cheek, it is also what has made the trend a focal point of criticism recently. Chinese cultural identity is turned into a game, a disposable trend for non-Chinese users. Some Chinese and Chinese-American creators have taken offense at how casually Chinese identity is treated—particularly after being a target of discrimination during the Covid era, only to now become a source of social-media hype.

Others argue that it feels more like appropriation than appreciation, suggesting that “Becoming Chinese” reflects a form of Orientalism: a simplified fantasy of an “exotic” China that mirrors Western desires, anxieties, and power relations rather than the lived realities of Chinese people.

Similar critiques have surfaced on Weibo, especially targeting Chinese-American social-media users. Some commenters accused them of seeking Western validation, framing their participation in the trend as an expression of unresolved insecurities about their own identity.

When confronted with such criticisms, some TikTok users respond defensively. One critical creator shot back at the “dumb comments” in his feed, saying: “Forget meeting you at a very Chinese time in your life—when am I going to meet you at a very intellectual time in your life?”

🇨🇳 “American society as a dystopian game”

The success of Lao-A’s descriptions of America’s dark sides and its “kill line” also lies in how he gamifies social stratification and marginalization. He does not just borrow terms from gaming, but frames society itself as a dystopian game, where reaching certain thresholds means it is simply game over.

While the “kill line” concept has been embraced by netizens and official media alike, the persona of Lao-A has grown increasingly controversial. As criticism mounted over inconsistencies and falsehoods in his stories about America, including his education and alleged “escape,” netizens began questioning how much was factual and how much was Hollywood-inspired: from slimy corpses in Seattle sewers to thriving black markets for organs, cannibalism or gangs beheading victims and hanging their skinned heads like “candied apples” (糖霜苹果).

In a recent livestream, Lao-A finally admitted that around “40 percent” of what he had told was not based on his own experience, with part drawn from borrowed accounts and part outright fabricated.

In a way, the popularization of Lao-A’s stories about the US resembles the wave of reporting about China’s “social credit score” in Western media between 2018 and 2020, when even reputable outlets claimed that the Chinese government was assigning all of its 1.4 billion citizens a personal score based on their behavior, linked to what they buy, watch, and say online. In many ways, those stories fed into Western fears about AI, privacy, and these developments becoming reality in Western societies themselves.

There was some truth in reports about the nascent social credit system in China, but much of the coverage was exaggerated or simply false—much like Lao-A’s stories, which mix real structural problems with a heavy dramatization and elements of fiction. In the end, that distinction matters less than you might expect. Lao-A has by now almost become a myth himself, praised by many not for the falsehoods he spread, but for consolidating a strong image of a dystopian America, one that balances the dark portrayal of China so often encountered in US media.

–Dynamics behind the trends

🔹Platform Politics

Both “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” are not just products of broader geopolitical shifts, US–China relations, and growing social insecurities. They are also inherently shaped by the platforms they emerged from and, in many ways, are products of those platforms themselves.

🇺🇸 “Chinese baddies building their TikTok success on Chinamaxxing”

In the West, “Becoming Chinese” trends are primarily created and shared on TikTok, an entertainment-focused platform built around endlessly scrolling short-form videos that are algorithmically recommended based on user behavior (particularly what people watch, engage with, or quickly scroll past). Although TikTok is originally Chinese—its parent company is ByteDance—it is separated from the app’s Chinese version (Douyin) and is only used outside China. TikTok has been popular in the US ever since its 2017 launch and is now used by some 200 million people there, with daily life, comedy, fashion & beauty and pop culture being among some of the popular content categories.

Since 2020, there have been repeated discussions about banning TikTok in the US over concerns about national security and the power of its algorithm due to its Chinese ownership—a prospect that proved widely unpopular among American TikTok creators. (As of this month, TikTok has finally reached a deal that allows the app to continue operating in the US, with its algorithm trained only on US data.)

As a result of this resistance against a potential ban, and against any policies changing the app’s dynamics, large numbers of users previously “fled” to the Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu, and began expressing overtly pro-China sentiments as a playful form of protest against what they saw as the anti-Chinese undertones of the proposed ban.

This background, along with the fact that TikTok is a platform generally focused on humor and relatability, has made it a place that is rather positive when it comes to China-related content. Earlier research confirms that, in sharp contrast to traditional US media, popular content on the app tends to frame China in a largely non-political and positive way.6

This has led to the current dynamics of the “Becoming Chinese” trend as a way for creators to profit. By creating these positive, entertaining, and short videos, they can aim for likes, build community, and grow their accounts. For a few “Chinese baddies,” their entire success was built on “Chinamaxxing.”

🇨🇳 “How to score on Bilibili”

In China’s social media environment, stories about the darker side of American society have always been a consistent part of online circles discussing US–China relations, and this holds especially true for Bilibili.

Although Bilibili originally started as a platform focused on ACG (anime, cartoons, games), it has evolved over the years along with its user base, which consists largely of college students and young professionals. It is now home to many creators producing political and geopolitical analytical content in a way that encourages interaction and aligns with Bilibili’s rather unpolished, humorous style.

Different from TikTok in America, popular Western-related content on China’s Bilibili platform is often framed through a strongly pro-Chinese lens and frequently carries anti-Western narratives. There are also foreign creators on the platform whose credibility is boosted when they produce what is considered pro-China or party-conforming content.7

Lao-A succeeded on Bilibili precisely because he tapped into what its users are most drawn to: using gaming slang and imagery to cast a dark light on American society on a platform whose users are increasingly politically engaged. At the same time, he claimed to be located in America itself, deep within the grim reality he described—further boosting his credibility.

In doing so, Lao-A showed that he understands how to “score” on Bilibili and has ultimately made an irreversible impact. The fact that he fabricated some of his stories does not seem to bother many people, who claim that being more nuanced would have simply led viewers to swipe away. These tactics have helped make him one of the most prominent “America watchers” on China’s social media in 2026.

🌀 Utopian Borrowing and Dystopian Pointing

Put side by side, “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” appear to be opposites: one romanticizes China, the other condemns America; one is playful and humorous, the other dark and serious; one thrives on Western social media, the other emerged from Chinese platforms; one is entertainment-driven, the other overtly political.

Yet both are built on similar foundations. Each taps into underlying anxieties and frustrations about the present, responds to broader global shifts, and relies on gamified language, stereotypes, or selective details that easily resonate with online audiences and encourage them to engage. In doing so, both trends are perfectly adapted to the platform dynamics and social media environments in which they flourish, and from which they benefit.

What these trends ultimately reveal is not a definitive truth about either country, but the power of digital discourse to seize on existing discontent to shape or influence perceptions of the United States and China. One becomes a utopia to borrow from, the other a dystopia to point at. Perhaps the most important takeaway is not how different these trends are, but how similar the underlying impulses behind these narratives actually are, revealing deeper ideas about American and Chinese internet users having so much more in common than meets the eye.

Meanwhile, Lao-A has already begun to move on a bit. His focus for now has shifted, at least partly, from America’s “kill line” to Japanese society. On TikTok, many of the creators who “discovered” they were “Chinese” in early January have also pivoted and are now posting about Pilates, reviewing Thai food, or booking holidays to Spain. Even “Perfect Angel,” who was the first to tweet that “Very Chinese time” phrase in 2025, just tweeted that “being Canadian is in this year.”

Who knows what we’ll become tomorrow? Maybe it really is time for that cup of hot water now.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 See: Elle Jones. 2026. “Why Everyone Is Now Chinese.” Substack, January 11. https://substack.com/home/post/p-184141480 [January 30, 2026].

2 See: Zeyi Yang and Louise Matsakis. 2026. “Why Everyone Is Suddenly in a ‘Very Chinese Time’ in Their Lives.” WIRED, January 16 https://www.wired.com/story/made-in-china-chinese-time-of-my-life/ [January 30, 2026].

3 See: Li Yuan. 2026. “Why China Is Suddenly Obsessed With American Poverty.” The New York Times, January 13 https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/13/business/china-american-poverty.html [February 1, 2026].

4 See: The Economist. 2026. “China Obsesses over America’s “Kill Line.”” The Economist, January 12 https://www.economist.com/china/2026/01/12/china-obsesses-over-americas-kill-line [February 1, 2026].

5 See: Ma Junjie. 2025. “A ‘Loser’s Nation’ and the Abandoned Chinese Dream.” The Diplomat, September 4. https://thediplomat.com/2025/09/a-losers-nation-and-the-abandoned-chinese-dream/ [February 3, 2026].

6 See: Cole Henry Highhouse. 2022. “China Content on TikTok: The Influence of Social Media Videos on National Image.” Online Media and Global Communication 1 (4): 697–722.

6 See: Florian Schneider. 2021. “China’s Viral Villages: Digital Nationalism and the COVID-19 Crisis on Online Video-Sharing Platform Bilibili.” Communication And The Public 6 (1-4): 48-66.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Chapter Dive

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

A look back at the three major phases of China’s social media — and why What’s on Weibo is evolving into Eye on Digital China.

Published

3 months agoon

November 12, 2025

This edition of the Eye on Digital China newsletter by Manya Koetse was sent to premium subscribers. Subscribe now to receive future issues in your inbox.

“Do you still remember going to the internet cafe, paying 2 yuan ($0.30) per hour during the day or 7 yuan ($1) for an all-nighter? Staying up playing games and surfing around?”

It’s the kind of content you’ll often see today on platforms like Douyin or Bilibili — nostalgic videos showing smoky internet cafes (wangba 网吧) from the early 2000s, where people chatted on QQ or played World of Warcraft on old Windows PCs while eating instant noodles. These clips trigger waves of nostalgia, even among internet users too young to remember that era themselves.

Internetcafe in 2005, image via 021zhaopin.com

The current nostalgia wave you see on Chinese social media is indicative of how China’s digital world has evolved over the past 25 years, shifting from one era to the next.

As I welcome a new name for this newsletter and say goodbye to ‘Weibo Watch’— and, in the longer run, to the ‘What’s on Weibo’ title, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic myself. It seems like a good moment to look back at the three major stages of Chinese social media, and at the reason I started What’s on Weibo in the first place.

1. The Blogging Boom (2002–2009): The Early Rise of Chinese Social Media

When I first came to China and became particularly interested in its online environment, it was the final phase of the early era of Chinese social media — a period that followed soon after the country had laid the foundations for its internet revolution. By 1999, the first generation of Chinese internet giants — Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Sina — had already been founded.

China’s blogging era began with the 2002 launch of the platform BlogChina.com (博客中国), followed by a wave of new platforms and online communities, among them Baidu Tieba and Renren. By around 2005, there were roughly 111 million internet users and 16 million bloggers, and the social impact was undeniable. 2005 was even dubbed China’s “year of blogging.” 1

Chinese writer Han Han (韩寒, born 1982), a high-school-dropout-turned–rally car racer, became one of the most-read figures on the Chinese internet with his sharp and witty blogs. He was just one among many who rose to fame during the blog era, becoming the voice of China’s post-1980s youth.

The rebel of China’s blog era, Han Han, became of voice of his generation.

When I moved to Beijing in 2008, I had a friend who was always out of money and practically lived in an internet cafe in the city’s Wudaokou district, not far from where I studied. We would visit him there as if it were his living room — the wangba was a local hangout for many of us.

Not only online forums and blogging sites were flourishing at the time, but there was also instant messaging through QQ (腾讯QQ), online news reading, and gaming. Platforms like the YouTube equivalents Tudou (土豆) and Youku (优酷) were launched, and soon Chinese companies began developing more successful products inspired by American digital platforms, such as Fanfou (饭否), Zuosa (做啥), Jiwai (叽歪), and Taotao (滔滔), creating an online space that was increasingly, and uniquely, Chinese.

That trajectory only accelerated after 2009, when popular Western internet services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, became inaccessible from within mainland China.

⚡ The launch of Sina Weibo in 2009 came at a crossroads for China’s social media landscape: it was not only a time when many foreign platforms exited China, but also when internet cafes faced major crackdowns.

As a foreigner, I don’t think I ever visited internet bars in Beijing anymore by that point — internet use had largely shifted to home connections. Laptop ownership was rising, and we all had (pre-smartphone) mobile phones, which we used to text each other constantly, since texting was cheaper than calling.

Some of the mobile phones in China’s 2009 top 10 lists.

Weibo came at just the right time. It filled the vacuum left by the online crackdowns across China’s internet while still benefiting from the popularity of blogging. Weibo (微博), after all, literally means “micro-blog” — micro because the number of characters was limited, just like Twitter, making short-form posts the main way of communication.

Weibo quickly became hugely successful, for many more reasons than just timing. Its impact on society was so palpable that its trending discussions often seeped into everyday conversations I had with friends in China.

In English-language media, I kept reading about what was being censored on the Chinese internet, but that wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to know — I also wanted to know what was on Weibo, so I could keep up with my social circles.

That question planted the seed for What’s on Weibo: the simple curiosity of “What are people talking about?” What TV series are popular? What jokes and controversies are everyone discussing (but that I never fully grasped)? I wanted to get a sense of an online world that was, in many ways, intangible to outsiders — including myself. As I had moved back to Europe by then, it was also a way for me to stay connected to those everyday conversations unfolding online in China.

With scissors, glue, and some paper, I started sketching out what a future website might look like.

Papercrafting the idea for a website named ‘What’s on Weibo’ in 2012.

And in March 2013, after doing my best to piece it together, I launched What’s on Weibo and began writing — about all kinds of trends, like the milk powder crisis, about China’s many unmarried “leftover men” (shengnan 剩男), and about the word of the moment, “Green Tea Bitch” (lǜchá biǎo 绿茶婊) — a term used to stereotype ambitious women who act sweet and innocent while being seen as calculating or cunning.

2. From Weibo to the Taobao Moment: China’s Mobile Social Era: (2010–2019)

Around 2014–2015, people started saying Weibo was dead. In fact, it hadn’t died at all — some of its most vibrant years were still ahead. It had simply stumbled into the mobile era, along with China’s entire social media landscape.

As mobile internet became more widespread and everyone started using WeChat (launched in 2011), new mobile-first platforms began to emerge.2 In 2012–2013, for example, apps like Toutiao and Xiaohongshu (小红书, RED) were launched as mobile community platforms. With the rapid rise of China’s new tech giants — Bytedance, Meituan, and Didi — a new mobile era was blossoming, leaving the PC-based social media world far behind.

Spending another summer in Beijing in 2014, I called it the “Taobao Moment” — Taobao being China’s most successful online marketplace, a platform for buying and selling practically everything from clothes and furniture to insurance and even Bitcoins. At the time, I thought Taobao captured everything Beijing was at that moment: a world of opportunities, quick decisions, and endless ways to earn and spend money.

On weekends, some of my friends would head to the markets near the Beijing Zoo to buy the latest dresses, purses, jeans, or shoes. They’d buy stock on Saturday, do a photo shoot on Sunday, and sell the goods online by Monday. You could often spot young people on the streets of Beijing staging their own fashion shoots for Taobao — friends posing as models, Canon cameras in hand.

During that period, What’s on Weibo gradually found its audience, as more people became curious about what was happening on Chinese social media.

Around 2016, Weibo entered another prime era as the “celebrity economy” took off and a wave of “super influencers” (超级红人) emerged on the platform. Papi Jiang stood out among them — her humorous videos on everyday social issues made her one of China’s most recognizable online personalities, helping to drive Weibo’s renewed popularity.

Witty Papi Jiang was a breath of fresh air on Weibo in 2016.

People were hooked on social media. Between 2015 and 2018, China entered the age of algorithm- & interest-driven multimedia platforms. The popularity of Kuaishou’s livestreaming and Bytedance’s Douyin signaled the start of an entirely new era.

3. The New Social Era of AI-fication and Diversification (2020–Current)

China’s social media shifts over the past 25 years go hand in hand with broader technological, social, and geopolitical changes. Although this holds true elsewhere too, it’s especially the case in China, where central leadership is deeply involved in how social media should be managed and which direction the country’s digital development should take.

Since the late 2010s, China’s focus on AI has permeated every layer of society. AI-driven recommendation systems have fundamentally changed how Chinese users consume information. Far more than Weibo, platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu have become popular for using machine-learning algorithms to tailor feeds based on user behavior.

China’s social media boom has put pressure on traditional media outlets, which are now increasingly weaving themselves into social media infrastructure to broaden their impact. This has blurred the line between social media and state media, creating a complex online media ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s not just AI and media convergence that are reshaping China’s online landscape — social relationships now dominate both information flows and influence flows. 3 Not everyone is reading the same headlines anymore; people spend more time within their own interest-based niches. It’s no longer about microblogging but about micro-communities.

China now has 1.12 billion internet users. Among new users, young people (aged 10–19) and the elderly (60+) account for 49% and nearly 21%, respectively. The country’s digital environment has never been more lively, and social media has never been more booming.

As a bit of a dinosaur in China’s social media world, Weibo still stands tall — and its trending topics still matter. But the community that was once at the heart of the Chinese internet has dispersed across other apps, where people now engage in more diverse ways than ever.

In China, I notice this shift: where I once saw the rise of Weibo, the Taobao boom, or the Douyin craze, I now see online and offline media increasingly converging. Social media shapes real-life experiences and vice versa, and AI has become integrated into nearly every part of the media ecosystem — changing how content is made, distributed, consumed, and controlled.

In this changing landscape, the mission of What’s on Weibo — to explain China’s digital culture, media, and social trends, and to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online spaces — has stayed the same. But the name no longer fits that mission.

Over the past few years, my work has naturally evolved from Weibo-focused coverage to exploring China’s digital culture through a broader lens. The analysis and trend updates will continue, but under a new name that better reflects a time when Weibo is no longer at the center of China’s social media world: Eye on Digital China.