Chapter Dive

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

From historic speeches to trending slogans, this is China’s official media response to the US tariff escalation.

Published

10 months agoon

What do Mao’s 1953 Korean War speech and Yang Jiechi’s 2021 Alaska Summit remarks have to do with the escalating US–China trade war? In Chinese official media responses, history and emotionally charged rhetoric are used to clearly signal China’s stance and boost national confidence. Here, we explore three dominant narratives.

As you probably know by now, April 9 marked “D-Day” for Trump’s rollout of steep tariffs. On Chinese social media, the escalating trade war between China and the US dominated conversation, especially on that “D-Day Wednesday,” when nearly all of Weibo’s top 10 most-viewed hashtags were related to Trump’s tariffs and China’s retaliation.

Since developments are unfolding rapidly, here’s a quick recap:

- 🇺🇸💥 On Wednesday, April 2, President Trump announced steep new tariffs, including a universal 10% “minimum base tariff” on all imported goods, and an additional 34% reciprocal tariff specifically targeting China as part of the so-called “Liberation Day,” set to begin on April 9. Combined with pre-existing tariffs, this would bring the total tariff rate on Chinese goods entering the United States to over 54%.

- 🇨🇳⚔️On Friday, April 4, China’s State Council Customs Tariff Commission Office issued an announcement stating that, starting April 10, an additional 34% tariff would be levied on all imported goods originating from the United States, on top of existing tariff rates.

- 🇺🇸⚔️On Tuesday, April 8, Trump vowed to increase tariffs on Chinese exports by an additional 50% if Beijing would not withdraw its 34% counter-tariffs.

- 🇨🇳💥On Wednesday, April 9, China’s finance ministry announced it would further raise tariffs on US goods to 84% starting the following day, in retaliation for the newly imposed 104% tariff on Chinese goods.

- 🇺🇸💣On Wednesday, April 9, Trump then did a U-turn and halted the new steep tariffs for dozens of countries for 90 days, except for China, followed by yet another threat of an additional 21%, bringing those import taxes to 125%.

- 🇺🇸🚨On Thursday, April 10, it was clarified by the White House that tariffs on China would actually total 145%, combining the previously announced 125% with a 20% import tax levied for fentanyl smuggling.

- 🇨🇳💣On Friday, April 11, Chinese official channels reported that China would adjust its tariff measures on important goods from the US starting April 12, raising the rate from 84% to 125%. A related hashtag became no 1 trending topic on Weibo, where it received over 500 million views by Friday night (#对美所有进口商品加征125%关税#).

- 🇺🇸⬅️ On Friday, April 11, Trump’s administration announced that it will exempt smartphones, computers and some other electronic devices from the new tariffs, including the 125% levies imposed on Chinese imports (#特朗普政府再度退缩#; #美国免除智能手机电脑对等关税#).

There are hundreds of hashtags and trending topics circulating across Chinese platforms — from Weibo to Toutiao, from Kuaishou to Douyin — related to the latest developments in the US–China trade war. The topic is super popular, but censored comment sections and removed images also reveal just how sensitive it can be at times.

The biggest hashtags and slogans are those initiated and amplified by official channels. From press conferences to hashtags and visual propaganda, you can see a clear strategic media narrative that draws on history, national pride, and patriotism to frame recent developments, mobilize public sentiment domestically, and show China’s resilience to the rest of the world.

Here, I’ll highlight three hashtags that have recently become top trending, each representing a different kind of official narrative or rhetoric in response to the ongoing developments.

1. China Won’t Back Down

(China will see it through to the end #美方一意孤行中方必将奉陪到底#)

The message that China will not be intimidated by the US is one that echoes across Chinese social media these days, reinforced by official channels.

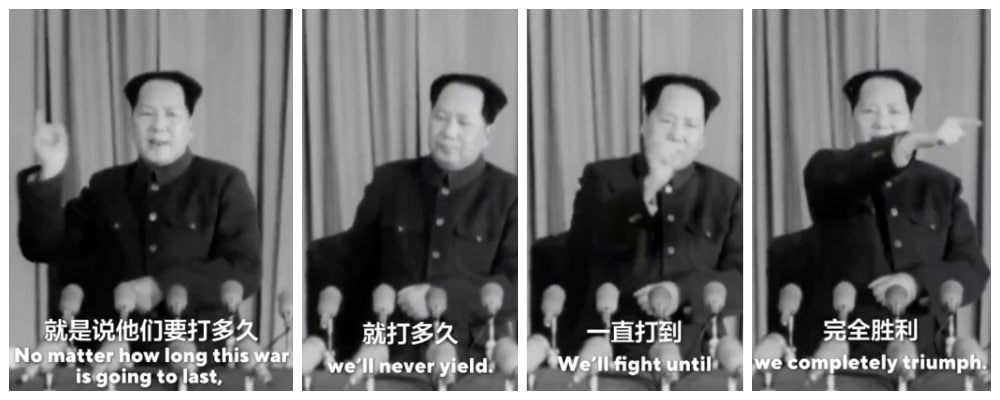

On April 9, the Weibo account of Chinese media outlet Guancha (@观察者网) and the state-run New Era China Foreign Affairs Think Tank (@新时代中国外交思想库) posted a video showing part of a speech given by Mao Zedong on February 7, 1953, during the final stages of the Korean War at the 4th Session of the 1st National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).

In the short fragment, Mao Zedong says:

🇨🇳📢 “As to how long this war will last, we are not the ones who can decide. It used to depend on President Truman, and it will depend on President Eisenhower, or whoever becomes the next US President. It’s up to them. No matter how long this war is going to last, we’ll never yield. We’ll fight until we completely triumph.”

The 1953 speech by Mao was also posted on the US social media platform X by Mao Ning (@毛宁), spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The video was then also spread by blogging accounts and regular netizens. History blogger Zijin Gongzi (@紫禁公子), who has over 435k fans on Weibo, reposted the video, writing:

💬 “Our forefathers never bowed their heads to strong enemies. How could we easily accept defeat? (..) We must not lose this spirit, we must let everyone know that we have a strong backbone and will never bow down.”

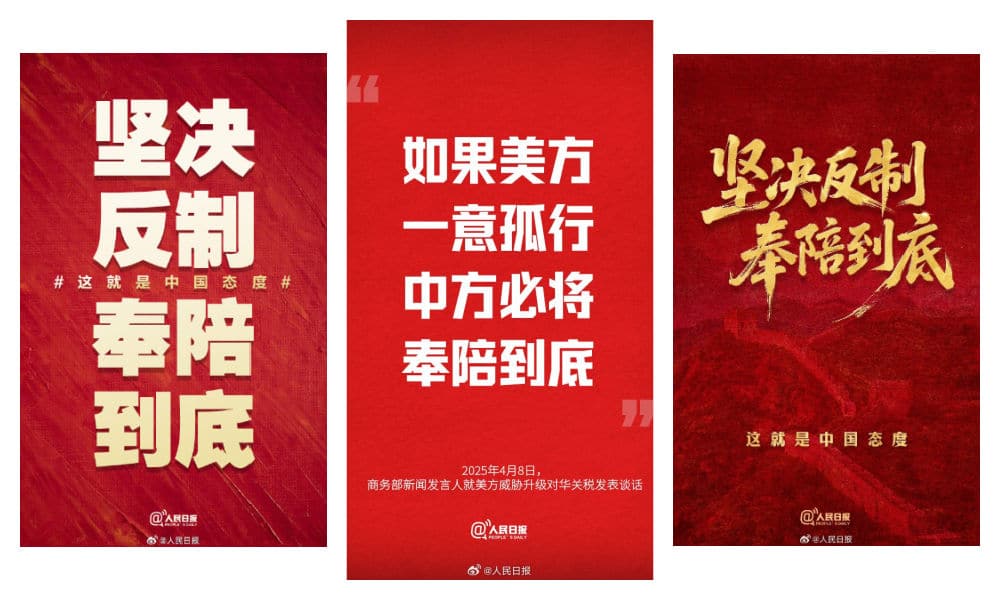

Together with the Mao video, the hashtag used by the Think Tank and many other Chinese media accounts, such as People’s Daily (@人民日报), is “If the US obstinately clings to its course, China will fight to the end [lit. accompany them to the end]” (#美方一意孤行中方必将奉陪到底#) and “fight to the end” (#我们奉陪到底#).

These phrases in part come from a press conference given by Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Lin Jian (林剑) on April 8. Here, he said:

🇨🇳📢 “I want to emphasize once again that there are no winners in trade wars and tariff wars, and protectionism is no way forward. The Chinese people do not provoke trouble, but they are also not afraid. Pressure, threats, and blackmail are not the proper ways to deal with China. China will inevitably take necessary measures and resolutely safeguard its legitimate rights and interests. If the American side disregards the interests of both countries and the international community and insists on waging a tariff war and trade war, China will fight to the end [lit. inevitably accompany them to the end 中方必将奉陪到底].”

The next day, these words had been turned into digital propaganda posters, with some slight variations in the phrases used. One People’s Daily graphic underlined: “We resolutely take countermeasures, and follow through until the end (坚决反制 奉陪到底),” accompanied by the line: “This is China’s attitude,” which was also turned into a hashtag (#这就是中国态度#).

2. This Is No Way to Deal with China

(Chinese people aren’t buying it #中国人从来不吃这一套#)

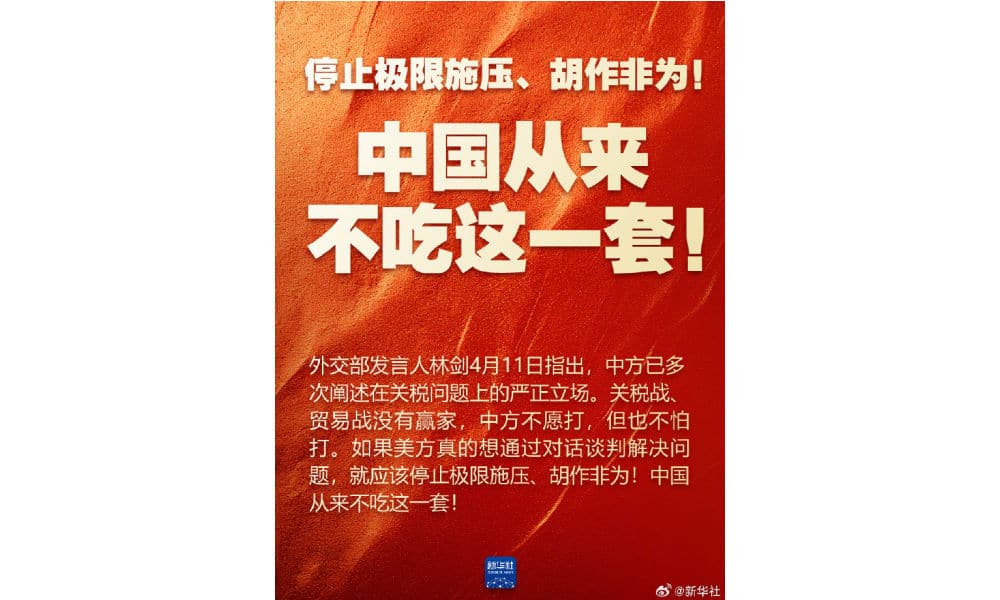

Another related yet somewhat different sentiment that dominates Chinese social media—led by official channels—is that China is not only rejecting the trade games played by the US, but is also distancing itself from the American playbook. The message is: this is no way to deal with China. This narrative, and the hashtag surrounding it, emerged slightly later than the first. While the earlier phrase about China not backing down trended as China matched the US in its tariff measures, this one took off with China’s final blow—raising the rate on US imports from 84% to 125% in response to the latest US tariff hikes.

The April 11 statement on the Ministry of Finance website (财政部网站), also posted on Weibo by Xinhua News (@新华社), announced that China would adjust its additional tariff measures on imports originating from the United States effective April 12. It also stated that China strongly condemns the US imposition of excessively high tariffs and will no longer engage in further tariff escalations:

🇨🇳📢 “Given that, at the current tariff level, US goods entering China effectively have no market viability, if the US continues to raise tariffs on Chinese exports to the US, China will no longer respond.”

The main hashtag used by Xinhua and many other media channels is “中国从来不吃这一套” (Zhōngguó cónglái bù chī zhè yī tào), which can be translated as: “The Chinese people have never accepted this,” or more colloquially, “We’re not buying it.”

The phrase initially became popular in 2021, after it was used by China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi (杨洁篪) during the first major strategic talks of the Biden administration, held in Anchorage on March 19. Due to the occasionally heated exchanges between the two delegations, some called the Alaska talks a “diplomatic clash.”

Yang Jiechi during the Alaska Summit

At the time, Yang delivered a lengthy statement to US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, stressing that Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang are “inseparable parts of China,” and that China strongly opposes US interference in its internal affairs. Suggesting the US should focus more on its own human rights issues and racial problems instead of lecturing China, he added the now-famous line: “The US is not qualified to speak to China from a position of strength. The Chinese people don’t buy that” (美国没有资格居高临下同中国说话,中国人不吃这一套).

The phrase quickly went viral—boosted by state media, celebrated by netizens, and turned into a marketing slogan. It now appears on t-shirts, teacups, phone cases, and other patriotic merchandise.

The translation of the phrase still triggers discussions. While merchandise typically translates it as “Stop interfering in China’s internal affairs,” that’s not an accurate translation. During the Alaska Summit, interpreter Zhang Jing (张京) (who gained viral fame at the time) translated it in real-time as “This is not the way to deal with the Chinese people.” However, some commentators and professional translators argued this was a missed opportunity to take a tougher stance, as the Chinese phrase is much sharper and could be loosely translated as: “We Chinese people don’t swallow this crap.”

In Alaska, Yang emphasized that dealing with China requires mutual respect, and that history will prove that trying to strangle China’s rise would ultimately hurt the US itself (“与中国打交道,就要在相互尊重的基础上进行。历史会证明,对中国采取卡脖子的办法,最后受损的是自己。”)

Similar sentiments now dominate online media discourse in China. The slogan has evolved from “The Chinese people don’t buy this” (中国人不吃这一套) to the more authoritative “China has never bought this” (#中国从来不吃这一套#)

Adding fuel to this message are hashtags like “America’s repeated imposition of excessively high tariffs on China has become a joke” (#美方对华轮番加征畸高关税已沦为笑话#).

Ridiculing America (especially Trump) has become a popular pastime on Chinese social media this past week, with a flood of Chinese and international memes circulating widely.

Especially popular are memes mocking the idea of America as a future “Made-in-America” manufacturing hub, the irony of iconic American products (like MAGA hats) being made in China, and how everyday essentials such as eggs have reached historic price highs in the US (a crisis partly caused by bird flu but now worsened by the tariffs).

On April 13, the hashtag “The 145% tariff makes one panda plush toy cost 80 dollars” (#145%关税让1只熊猫玩偶卖80美元#) also went trending, sparking jokes about how even the most trivial things could suddenly become luxuries in the US.

3. China is the Most Stabile Superpower

(Countering America’s madness with China’s stability #以中国稳应对美国疯#)

A third stance that has been dominant in Chinese official online discourse is that China’s development does not rely on anyone’s favors (#中国发展从不靠谁的恩赐#, derived from a quote by Xi Jinping), and that despite the US’s measures, China’s rise on the world stage cannot be stopped. In fact, the narrative suggests that these actions by the US are only accelerating China’s ascent.

A commentary piece published by state broadcaster CCTV (@央视新闻) on April 11 quoted Professor Li Haidong (李海东) of China Foreign Affairs University, who stated that the US’s increasingly aggressive behavior reinforces the notion that it is using tariffs as a tool of extreme pressure; as a weapon to serve its own interests. According to Li, this reflects America’s hegemonic mindset, aiming to assert superiority by intentionally creating crises.

But rather than strengthening the US, the commentary argues, these recent measures are backfiring and are damaging the US’s domestic economy and undermining its global credibility.

In contrast to the US’s presumed recklessness and “hysterical approach,” China is depicted as a “responsible world leader,” bringing certainty to an uncertain world by “responding with its own stability” and proving to be, supposedly, a more reliable engine of global growth. The commentary states:

🇨🇳📢 “As the tariff storm strikes, China is using its own ‘stability’ to resist the trials and tribulations, by upholding rules, defending justice, and steering the big ship of globalization through treacherous countercurrents, toward the right path of openness and cooperation.”

To promote the piece on social media, CCTV used the hashtag “Responding to America’s madness with China’s stability” (#以中国稳应对美国疯#).

This sentiment was echoed by nationalist bloggers, such as Tangzhe Tongxue (@唐哲同学), who posted on April 13:

💬 “In this world, besides China, the rest are all just a poorly equipped small-town theater troupe (草台班子).”

The phrase “草台班子” (cǎotái bānzi) literally refers to a makeshift opera troupe performing on a shabby rural stage, and is used to describe an incompetent group of amateurs.

The blogger’s comment indirectly responds to comments made by US Vice President JD Vance, who defended Trump’s tariffs in a Fox News interview by saying: “To make it a little more crystal clear, we borrow money from Chinese peasants to buy the things those Chinese peasants manufacture.”

That remark sparked controversy online, with many netizens calling it ignorant. Some pointed out that Chinese people were already wearing fine silks when Westerners were still wrapped in animal skins fishing in the sea, and flipping the narrative to portray Americans as the real “country bumpkins.”

Meme shared online.

This sentiment was reinforced by another hashtag trending on Weibo on April 13: “You think we’re scared, but we actually don’t care” (#你以为我们scared其实我们不care#).

That line comes from a Channel 4 interview with Gao Zhikai (Victor Gao/高志凯), Vice President of the Center for China & Globalization (CCG), who stated:

🇨🇳📢 “China is fully prepared to fight to the very end. Because the world is big enough that the United States is not the totality of the market in the world. So if the United States wants to go in that direction of completely shutting itself out of the Chinese market, be my guest. [Interviewer: Yes and China will lose the US market..] We don’t care. We don’t care. China has been here for 5000 years, and for most of the time there was no United States and we survived. If the United States wants to bully China, we will deal with the situation without the United States. And we except to survive for another 5000 years.”

While this reflects the official position and is widely echoed across social media, others stress the importance of remembering history; particularly China’s “Century of Humiliation” (百年国耻), which was marked by war, aggression, and unequal treaties imposed by foreign powers. Just like other historical anniversaries, some bloggers argue that Trump’s tariff “D-Day,” April 9, should not be forgotten (“今天是每个中国人难以释怀的日子”) and that it marks another reason for China’s renewed rise.

In a video posted by CCTV’s short video platform Xiaoyang Shipin (小央视频) on April 13 (link), the narrator states:

🇨🇳📢 “The so-called global “beacon” now puts “America first.” It slaps allies in the face, treats the world with predatory practices, and makes other countries pay for MAGA, pushing the fragile word economy over the edge, and pitching itself against the whole world. With China here, the sky won’t fall. With around 5% economic growth, China adds the output of a mid-sized European economy every year. China has hundreds of millions of skilled workers. The Chinese people are well known for their strong work ethic. China’s development over the past seven decades is a result of self-reliance and hard work, not favors from others, (..) Global businesses believe the next China is still China and the best is yet to come (..) Markets need to restore faith. Between the pond of closed markets, and the ocean of economic interconnectivity, which one would you choose?”

Overall, packaged across different media — from hashtags to short videos, from press conferences to news reports, and from digital slogan posters to Ministry of Foreign Affairs tweets — China’s strategic political media messaging is clear and quite powerful, despite the fragile and censored environment it operates in: China is not afraid to strike back, China will lead with calm, and eventually, China will emerge as the winner. Whatever happens next remains to be seen, but when it comes to turning crisis into opportunity, China’s official media channels have already done just that.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF WHAT’S ON WEIBO CHAPTER: “THE US-CHINA TARIFF WAR ON CHINESE SOCIAL MEDIA“

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Chapter Dive

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

We’re at a very complicated time in our online lives. An explainer of “Chinamaxxing,” the “kill line,” and the platform politics behind them.

Published

2 weeks agoon

February 3, 2026

While American TikTok users find themselves in a “very Chinese time” of their lives, Chinese netizens are fixated on the American “kill line.” Beyond the apparent digital divide, both trends reflect shared anxieties and shifting power dynamics between the US and China.

In the first month of 2026, two noteworthy social-media trends, both telling of the times we live in, went viral in the US and China: a China-focused trend in the US and an America-focused one in China.

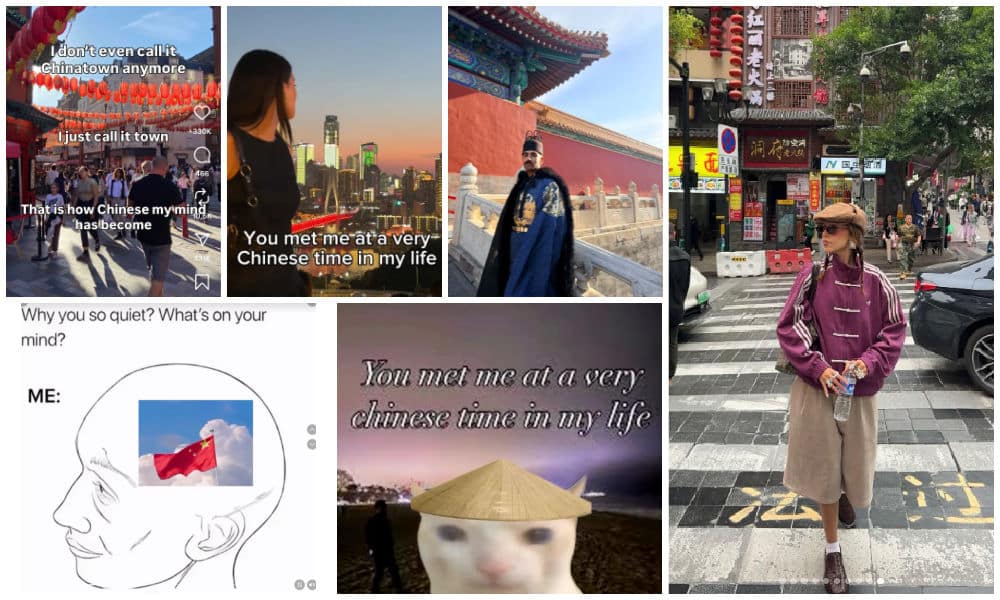

In the US, TikTok videos and Instagram posts showing young people cheerfully portraying themselves as “Chinamaxxing,” or being “in a very Chinese time” of their lives, began popping up across social media.

Meanwhile, in China, posts about the darker side of American society and its so-called “kill line” (斩杀线) dominated trending lists.

In this week’s chapter dive, I’ll explain the stories behind both of these trends and why, despite their very different implications, the dynamics driving them are strikingly similar.

Converting to “Chinese Baddies”

Over the past week, the phrase “Becoming Chinese” (成为中国人 chéngwéi Zhōngguórén) has been gaining traction on Chinese social media. On January 30, the headline “Why ‘Becoming Chinese’ Videos Are Going Viral’ even made it to the number one most popular topic on Chinese platform Toutiao (“成为中国人视频为什么火了”).

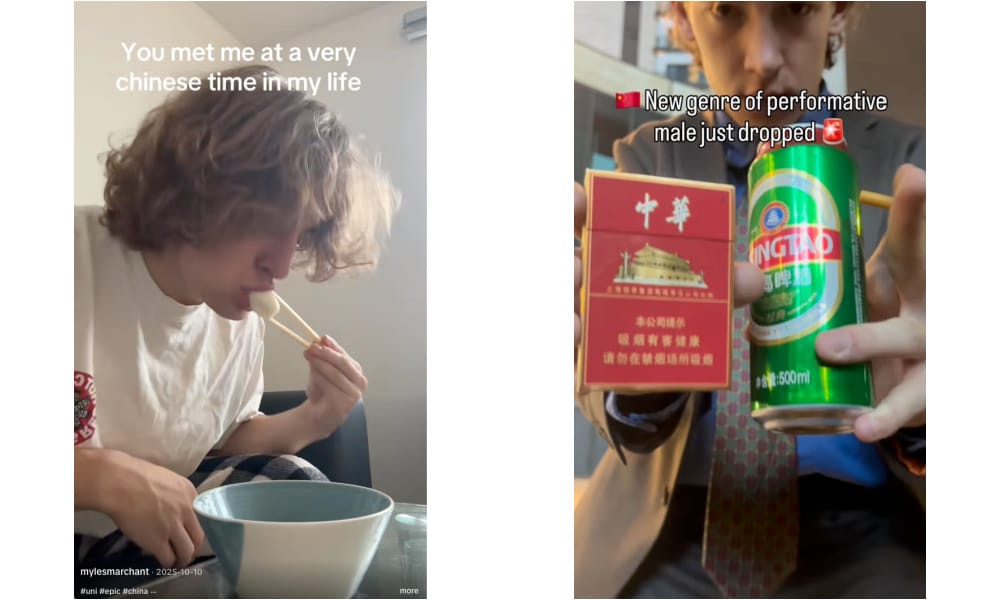

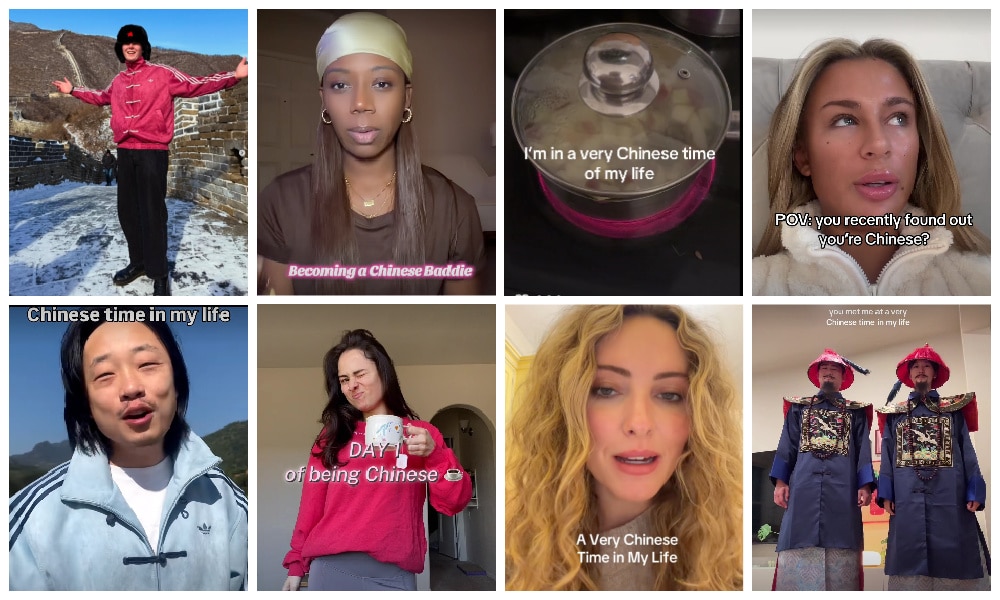

Before reaching China’s social media, the trend had been gaining momentum on TikTok and Instagram for months, with viral videos showing foreigners humorously flaunting their supposedly deep connection to China by doing things like drinking a nice cup of hot water (the solution to everything), using traditional Chinese medicine, sitting in a squatting position while smoking Chinese cigarettes and holding Tsingtao beer, eating noodles or dim sum—all while wearing that popular Adidas “Chinese jacket.”

This is all referred to as “Chinamaxxing” or “Chinesemaxxing”: optimizing life by living in a Chinese-coded way.

Various “very Chinese time” examples (TikTok/Instagram).

The build-up to this moment has actually been underway for several years. In the post-Covid era, China’s global pop culture influence has grown noticeably, driven both by increasingly outward-facing efforts from Chinese companies and state actors, and by a broader shift among younger audiences in the US toward Asia.

As part of this broader shift, several notable online moments have emerged over the past few years, including the viral success of a Chinese pop song in 2022; the 2024 breakout of Black Myth: Wukong; the 2025 “TikTok refugee” phenomenon; Chinese rapper SKAI ISYOURGOD becoming a staple on TikTok; and the widely watched March 2025 China tour of American YouTuber IShowSpeed, followed by a less impactful but still meaningful China visit by American influencer Hasan Piker.

The now-famous line “You met me at a very Chinese time in my life”—inspired by the quote “You met me at a very strange time in my life” from the final scene of Fight Club—first surfaced on X in April 2025. The X account “Perfect Angel” (@girl__virus) then posted the phrase in a tweet that since has gathered over 950,000 views.1

The X post of April 5, screenshotted Jan 30, 2026.

The trend snowballed from there, especially in October 2025. When creator Myles Marchant posted a video of himself eating dumplings while using the phrase, it received nearly 200k likes. Afterward, all kinds of internet users, but particularly American content creators, started using the phrase in videos to show off just how “Chinese” they were.

Myles Marchant and McMungo in their videos.

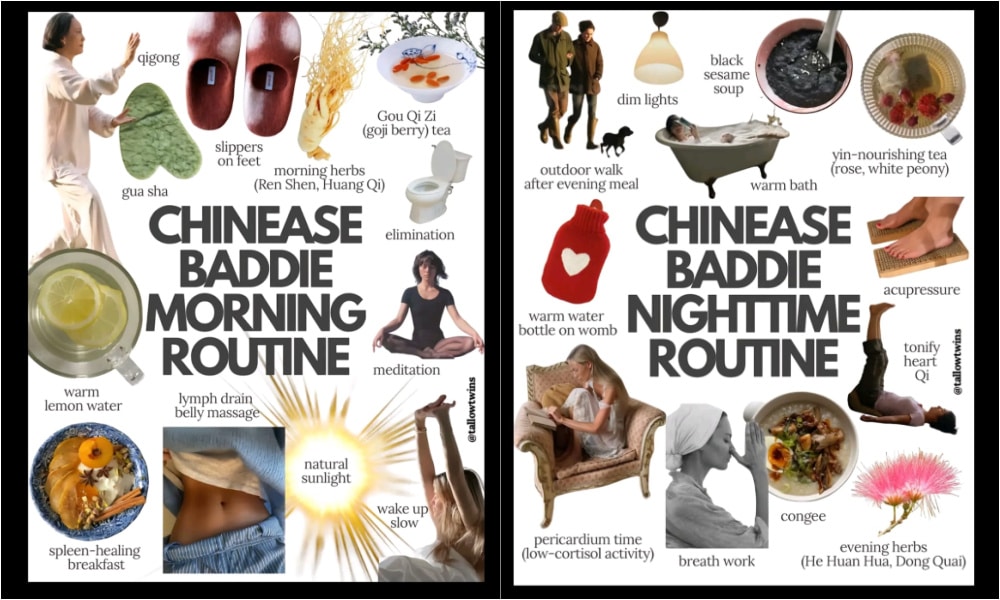

As the meme went viral, from October 2025 through January 2026, it continued to evolve. What began with cigarette smoking and playful performances of “Chinese” behavior has, for many TikTok users, grown into something more. Drawing on Chinese food philosophies and wellness practices, they now present “Becoming Chinese” as a lifestyle trend focused on better energy, health, and skincare.

Chinamaxxing, Chinese Baddies, Becoming Chinese, A Very Chinese Time of My Life: Trends on Tiktok.

TikTok creator Missmazz, for example, introduced her morning routine “since recently converting to Chinese”: wearing slippers in the house, doing small jumps to “activate” lymph nodes, and drinking warm water and herbal tea. Creator Ohplsnatagain also shared her “first day of being Chinese,” drinking ginger tea, boiling apples, wearing red, and avoiding cold drinks.

“Chinease” morning and night routines, shared on TikTok by Tallow Twins.

Besides those aspiring to become Chinese, some Chinese creators have expressed their joy about the trend others emerged as online guides to these newly adopted identities and lifestyles. Creators like Emma Peng made a video telling people, “my culture can be your culture,” while others, like Sherry, actively encourage people to become Chinese: “It’s gonna be so fun!”

They have now formed an online community of self-labeled “Chinese baddies,” sharing recipes, morning routines, and tips for being as ‘Chinese’ as possible. On Chinese social media, netizens are humored by the overseas trend, and see it as a sign of just how powerful Chinese cultural confidence has become (“藏在烟火气里的文化自信才最有感染力”).

America’s “Kill Line”

While American social media users have been busy Chinamaxxing, Chinese social media have been feverishly discussing America’s so-called “kill line” (also translated as “execution line,” 斩杀 zhǎnshāxiàn).

The term first went trending in late 2025 after it was coined by the Northern Chinese livestreamer Squishy King (斯奎奇大王), better known by his nickname “Lao-A” (牢A), who is particularly active on Bilibili, the Chinese platform known for its strong anime and gaming subculture.

Lao-A has been livestreaming since 2024 without ever showing his face on camera. Through pure voice narration over images, he became known for casually chatting in livestreams—sometimes lasting over five hours—about a wide range of topics, especially those connected to American society. Lao-A claimed he was a Chinese biomedical student in Seattle who worked part-time as a forensic assistant, handling unclaimed bodies and preparing them for medical education or research.

Profile image of “Lao A”, who never shows his face on streams.

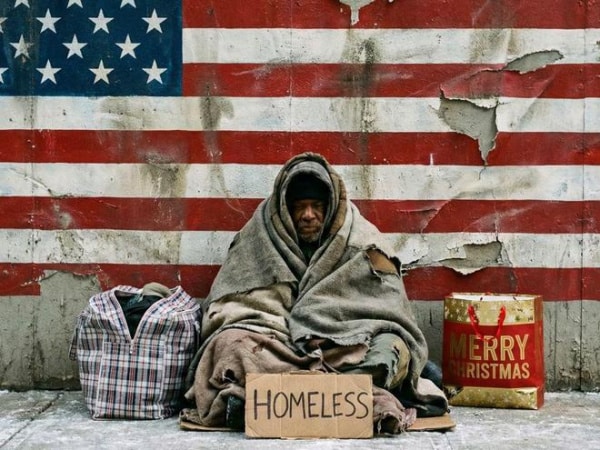

On November 1, 2025, during a stormy Halloween Friday night, Lao-A hosted another one of his five-plus-hour live-chatting streams, in which he spoke about the bad weather and homelessness in the US.

He mentioned how people living on the streets could easily die from a cold or Covid that turns into pneumonia without proper treatment, and how dreadful he felt about the freezing conditions—knowing that on Monday he would see the bodies of people who had died on the streets that very weekend.

According to Lao-A, the unidentified bodies of homeless people would be brought by the police to his school, where they could still generate some value. Drawing comparisons to “harvesting in harsh winter,” he introduced the concept of the “kill line,” borrowing the term from multiplayer/role-playing games such as Hades or League of Legends.

In gaming, a “kill line” refers to the health-point (HP) threshold below which a character can be instantly killed, with no possibility of recovery. Lao-A suggested that the situation of marginalized and homeless people during Seattle’s winter was similarly bleak: their deaths are treated as almost inevitable, even though basic medical care—such as antibiotics—might prevent them.

The way Lao-A spoke about his work and the darker sides of American society spread rapidly through Bilibili’s comment culture and then into wider Chinese social media, especially as he expanded on the topic in other livestreams, where he further discussed poverty in America, from the healthcare system to food assistance programs.

Visuals accompanying a report about Lao-A on the 163.com website.

Lao-A particularly focused on medical bills as a key component of America’s “kill line.” He described how people suffer first and then seek care, only to be further burdened by crushing costs—arguing that the American system drains people at their most vulnerable. An unexpected event such as illness, job loss, or a car breakdown can suddenly disrupt a family’s cash flow, leading to unpaid bills and a collapse in credit scores. Bad credit, in turn, makes it harder to rent housing, pass background checks, or secure affordable insurance, while debts pile up. This downward spiral, he suggested, eventually pushes people past a final execution threshold: too broke, too sick, too depressed, and too far gone to recover, ending in homelessness or addiction and shortening life spans.

Lao-A framed this as a systemic trap created by capitalism: a game mechanic in which the rules are rigged so that once someone falls below the threshold, the system itself kills them. Besides the “kill line,” he introduced other gaming-inspired terms, such as using “Gundam” (高达, after the Japanese model kits) to refer to the bodies he handled, or “slimes” (史莱姆) for decomposed bodies found in sewers.

In some ways, Lao-A’s “kill line” resembles the concept of ALICE (“Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed”), a demographic category created by the nonprofit United For ALICE to describe American households that earn above the federal poverty line but still cannot afford basic necessities such as housing, childcare, healthcare, or groceries.

By mid-December 2025, the term and the stories surrounding it had entered the mainstream and began hitting trending lists on Weibo, Toutiao, and Kuaishou.

Cartoon by Chinese state media outlet CRI Online about the killing line. Top texts say: “Thriving economy, America first, America great again.” On the staircase, it says: “Unemployment, unexpected costs, illness.”

As the “kill line” quickly entered China’s online lexicon, it was also embraced and boosted by official media. After earlier coverage, Qiushi (qstheory), the Chinese Communist Party’s most authoritative theoretical journal, published a January 4 commentary arguing that the “kill line” reflects a widespread condition in which Americans’ capacity to withstand risk has been pushed to its limits, while Trump’s MAGA movement fails to work towards a solution as it focuses on cultural identity rather than addressing the economic challenges faced by millions of Americans.

Something that also caused a stir online, is how American media began reporting on the Chinese “kill line” concept. First Newsweek on December 26, followed by The Economist and later The New York Times. The phrase even surfaced at the World Economic Forum in Davos, when a Chinese state-media reporter asked US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent about the phenomenon.

All of this placed a considerable spotlight on Lao-A himself, whose real identity and personal backstory began to be questioned by internet users. After he was identified as the possibly 30-year-old “Alex Kong 孔” from Daqing, who attended a community college in Seattle, more of his details were leaked online. Lao-A said he feared for his safety and returned to China.

This supposed “escape from America” became a major story on Chinese social media, with Lao-A repeatedly topping trending charts from January 17 onward. Attention peaked around January 22–23, after he joined Weibo and participated in joint livestreams with Chinese professor and prominent nationalist commentator Shen Yi (沈逸), and again around February 1, when he streamed with foreign-policy commentator Gao Zhikai (高志凯). During this period, Lao-A and the dystopian “kill line” narrative completely dominated Chinese online discussions.

Throughout his solo livestreams and collaborative appearances, Lao-A has continued to paint an especially dark picture of American society, describing graphic gang violence, failures in the education system, murky organ-transplant systems and black markets for organ harvesting (claiming that healthy Chinese students who have not used drugs are “very valuable”), and Chinese female students abroad as “ideal hunting targets” for white men—explicitly warning Chinese parents not to send their daughters to study overseas.

By now, “kill line” is a term that pops up all over Chinese social media and is applied to all kinds of news coming from America, from the Epstein files to the Alex Pretti shooting.

Where the “Kill Line” Meets “Chinamaxxing”

On the famous Know your Meme website, the phrase “You Met Me At A Very Chinese Time In My Life” is described as “ultimately meaningless and purposefully absurd.” But it’s actually not.

Both the “Becoming Chinese” trend and the discourse surrounding the “kill line” are shaped by our current media moment and reflect broader, shifting narratives about China, the United States, and global power.

While China’s rise has been a major media theme for years, a lot of Chinese influence had felt invisible for younger generations in the West, even if they were already living, wearing, and consuming “made in China.” More recently, however, China’s soft power narratives have become more visible, with popular culture emerging as a powerful tool.

The changing attitudes toward “made in China,” alongside a growing interest in Chinese tradition and elements of ancient culture, took shape in the late 2010s as China’s domestic cultural confidence increased. This development was partly supported by China’s flourishing livestreaming economy & homegrown e-commerce platforms, as well as more assertive official messaging around the idea of products being “proudly made in China.”

Wang Yibo poses with Anta’s “China” t-shirt in 2021, the year that “made in China” had become cool again.

Younger Chinese consumers in particular—those born after 1995 or 2000—began showing more interest in domestic brands than earlier generations. This trend reflected not just consumer preference, but a stronger identification with Chinese culture and national identity. By 2021, a Global Times survey indicated that most Chinese consumers believed Western brands could be replaced by Chinese ones (75% of respondents agreed that “national products could fully or partially replace Western products“).

By 2025, pop-culture products emerging from this renewed focus on domestically produced goods—often incorporating traditional Chinese aesthetics—began reaching audiences beyond China, finding traction in Western markets as well.

At the same time, the United States experienced significant societal divisions in the aftermath of the 2024 elections, while its global image and cultural influence were affected by the dismantling of traditional US soft power channels.

Together, these developments shaped broader changes in global public opinion, tilting toward a more favorable view of China as “the world’s leading power,” and fueling conversations about a future increasingly framed through a Chinese lens.

This wider geopolitical context forms the backdrop against which the two viral trends discussed here took shape.

–Why these trends took off

🔹 The Decay of the American Dream and Insecurities about China’s Dream

Geopolitical power shifts alone are not enough to explain the virality of both “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” discourse. Current socio-cultural dynamics also play a major role.

In both the US and China, people’s sense of security, future, and identity is shifting, and other countries are increasingly used as mirrors, escape routes, or coping mechanisms to process that change. Young working-class Americans under Trump and middle-class Chinese facing “involution” (nèijuǎn 内卷, a seemingly never-ending societal rat race) are questioning their systems, but arrive at opposite conclusions by using each other as contrasts.

🇺🇸 “A projection of what Americans believe their own country has lost”

In a recent article for Wired,”Why Everyone Is Suddenly in a ‘Very Chinese Time’ in Their Lives,” the authors argue that the “very Chinese time” meme is “not really about China or actual Chinese people,” but instead functions as a projection of what Americans believe their own country has lost.2

Rather than offering an accurate depiction of China, the trend relies on stereotyped markers of “Chineseness” to express frustration with US infrastructure erosion, political instability, polarization and, as PhD researcher Tianyu Fang puts it, “the decay of the American dream.”

In this context, China appears as an aspirational contrast—”less as a real place than an abstraction”—through which Americans critique their own realities.

🇨🇳 “Why China is suddenly obsessed with American poverty”

Similarly, in a The New York Times article titled “Why China Is Suddenly Obsessed With American Poverty,” author Li Yuan argues that the “kill line” narrative offers emotional relief to Chinese netizens while also helping to deflect criticism of domestic leadership. As she writes, “the worse things look across the Pacific (…), the more tolerable present struggles become.”3

A related conclusion is reached in an article by The Economist,4 which suggests that the surge in discussion about America’s failures says less about the realities of life in the US than about China’s own anxieties over slowing growth and the fragility of domestic political discourse.

While the “Chinese Dream,” which prioritizes collective effort and national strength, is promoted as part of state ideology, everyday life tells a more sobering story, in which climbing the social ladder seems increasingly out of reach for millions of Chinese facing economic slowdown, high youth unemployment, and a constrained space for criticism.5

Yet as narratives about the perceived failure of the “American Dream” flood Chinese social media, China itself begins to look like the better place—even with all of its own challenges.

Ultimately, both the “Becoming Chinese” and “kill line” phenomena are embedded in collective anxieties about vulnerability and decline, fueling a growing hunger for counter-narratives.

–The stories told

🔹Fantasizing about “the Other”

Those counter-narratives do not need to be realistic. To fulfill their role in channeling perspectives, insecurities, and even a sense of cathartic relief about the present and future, they can’t actually be nuanced. Simplification, exaggeration, and symbolic contrast are precisely what make them effective.

🇺🇸 “Chinese cultural identity as a disposable trend”

In the case of “Becoming Chinese,” the trend is comically fairy-tale–like, suggesting that people of all backgrounds can “turn Chinese” in the blink of an eye. One popular meme even implies that there is no need to “kiss the frog” to meet the prince: simply looking at the frog would already make you Chinese.

Beyond fairy tales, there is also a gaming logic at play in other “Becoming Chinese” memes, with different levels of “Chineseness” to unlock to reach that final mythical state of Being Chinese.

Although this is all tongue-in-cheek, it is also what has made the trend a focal point of criticism recently. Chinese cultural identity is turned into a game, a disposable trend for non-Chinese users. Some Chinese and Chinese-American creators have taken offense at how casually Chinese identity is treated—particularly after being a target of discrimination during the Covid era, only to now become a source of social-media hype.

Others argue that it feels more like appropriation than appreciation, suggesting that “Becoming Chinese” reflects a form of Orientalism: a simplified fantasy of an “exotic” China that mirrors Western desires, anxieties, and power relations rather than the lived realities of Chinese people.

Similar critiques have surfaced on Weibo, especially targeting Chinese-American social-media users. Some commenters accused them of seeking Western validation, framing their participation in the trend as an expression of unresolved insecurities about their own identity.

When confronted with such criticisms, some TikTok users respond defensively. One critical creator shot back at the “dumb comments” in his feed, saying: “Forget meeting you at a very Chinese time in your life—when am I going to meet you at a very intellectual time in your life?”

🇨🇳 “American society as a dystopian game”

The success of Lao-A’s descriptions of America’s dark sides and its “kill line” also lies in how he gamifies social stratification and marginalization. He does not just borrow terms from gaming, but frames society itself as a dystopian game, where reaching certain thresholds means it is simply game over.

While the “kill line” concept has been embraced by netizens and official media alike, the persona of Lao-A has grown increasingly controversial. As criticism mounted over inconsistencies and falsehoods in his stories about America, including his education and alleged “escape,” netizens began questioning how much was factual and how much was Hollywood-inspired: from slimy corpses in Seattle sewers to thriving black markets for organs, cannibalism or gangs beheading victims and hanging their skinned heads like “candied apples” (糖霜苹果).

In a recent livestream, Lao-A finally admitted that around “40 percent” of what he had told was not based on his own experience, with part drawn from borrowed accounts and part outright fabricated.

In a way, the popularization of Lao-A’s stories about the US resembles the wave of reporting about China’s “social credit score” in Western media between 2018 and 2020, when even reputable outlets claimed that the Chinese government was assigning all of its 1.4 billion citizens a personal score based on their behavior, linked to what they buy, watch, and say online. In many ways, those stories fed into Western fears about AI, privacy, and these developments becoming reality in Western societies themselves.

There was some truth in reports about the nascent social credit system in China, but much of the coverage was exaggerated or simply false—much like Lao-A’s stories, which mix real structural problems with a heavy dramatization and elements of fiction. In the end, that distinction matters less than you might expect. Lao-A has by now almost become a myth himself, praised by many not for the falsehoods he spread, but for consolidating a strong image of a dystopian America, one that balances the dark portrayal of China so often encountered in US media.

–Dynamics behind the trends

🔹Platform Politics

Both “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” are not just products of broader geopolitical shifts, US–China relations, and growing social insecurities. They are also inherently shaped by the platforms they emerged from and, in many ways, are products of those platforms themselves.

🇺🇸 “Chinese baddies building their TikTok success on Chinamaxxing”

In the West, “Becoming Chinese” trends are primarily created and shared on TikTok, an entertainment-focused platform built around endlessly scrolling short-form videos that are algorithmically recommended based on user behavior (particularly what people watch, engage with, or quickly scroll past). Although TikTok is originally Chinese—its parent company is ByteDance—it is separated from the app’s Chinese version (Douyin) and is only used outside China. TikTok has been popular in the US ever since its 2017 launch and is now used by some 200 million people there, with daily life, comedy, fashion & beauty and pop culture being among some of the popular content categories.

Since 2020, there have been repeated discussions about banning TikTok in the US over concerns about national security and the power of its algorithm due to its Chinese ownership—a prospect that proved widely unpopular among American TikTok creators. (As of this month, TikTok has finally reached a deal that allows the app to continue operating in the US, with its algorithm trained only on US data.)

As a result of this resistance against a potential ban, and against any policies changing the app’s dynamics, large numbers of users previously “fled” to the Chinese social media app Xiaohongshu, and began expressing overtly pro-China sentiments as a playful form of protest against what they saw as the anti-Chinese undertones of the proposed ban.

This background, along with the fact that TikTok is a platform generally focused on humor and relatability, has made it a place that is rather positive when it comes to China-related content. Earlier research confirms that, in sharp contrast to traditional US media, popular content on the app tends to frame China in a largely non-political and positive way.6

This has led to the current dynamics of the “Becoming Chinese” trend as a way for creators to profit. By creating these positive, entertaining, and short videos, they can aim for likes, build community, and grow their accounts. For a few “Chinese baddies,” their entire success was built on “Chinamaxxing.”

🇨🇳 “How to score on Bilibili”

In China’s social media environment, stories about the darker side of American society have always been a consistent part of online circles discussing US–China relations, and this holds especially true for Bilibili.

Although Bilibili originally started as a platform focused on ACG (anime, cartoons, games), it has evolved over the years along with its user base, which consists largely of college students and young professionals. It is now home to many creators producing political and geopolitical analytical content in a way that encourages interaction and aligns with Bilibili’s rather unpolished, humorous style.

Different from TikTok in America, popular Western-related content on China’s Bilibili platform is often framed through a strongly pro-Chinese lens and frequently carries anti-Western narratives. There are also foreign creators on the platform whose credibility is boosted when they produce what is considered pro-China or party-conforming content.7

Lao-A succeeded on Bilibili precisely because he tapped into what its users are most drawn to: using gaming slang and imagery to cast a dark light on American society on a platform whose users are increasingly politically engaged. At the same time, he claimed to be located in America itself, deep within the grim reality he described—further boosting his credibility.

In doing so, Lao-A showed that he understands how to “score” on Bilibili and has ultimately made an irreversible impact. The fact that he fabricated some of his stories does not seem to bother many people, who claim that being more nuanced would have simply led viewers to swipe away. These tactics have helped make him one of the most prominent “America watchers” on China’s social media in 2026.

🌀 Utopian Borrowing and Dystopian Pointing

Put side by side, “Becoming Chinese” and the “kill line” appear to be opposites: one romanticizes China, the other condemns America; one is playful and humorous, the other dark and serious; one thrives on Western social media, the other emerged from Chinese platforms; one is entertainment-driven, the other overtly political.

Yet both are built on similar foundations. Each taps into underlying anxieties and frustrations about the present, responds to broader global shifts, and relies on gamified language, stereotypes, or selective details that easily resonate with online audiences and encourage them to engage. In doing so, both trends are perfectly adapted to the platform dynamics and social media environments in which they flourish, and from which they benefit.

What these trends ultimately reveal is not a definitive truth about either country, but the power of digital discourse to seize on existing discontent to shape or influence perceptions of the United States and China. One becomes a utopia to borrow from, the other a dystopia to point at. Perhaps the most important takeaway is not how different these trends are, but how similar the underlying impulses behind these narratives actually are, revealing deeper ideas about American and Chinese internet users having so much more in common than meets the eye.

Meanwhile, Lao-A has already begun to move on a bit. His focus for now has shifted, at least partly, from America’s “kill line” to Japanese society. On TikTok, many of the creators who “discovered” they were “Chinese” in early January have also pivoted and are now posting about Pilates, reviewing Thai food, or booking holidays to Spain. Even “Perfect Angel,” who was the first to tweet that “Very Chinese time” phrase in 2025, just tweeted that “being Canadian is in this year.”

Who knows what we’ll become tomorrow? Maybe it really is time for that cup of hot water now.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 See: Elle Jones. 2026. “Why Everyone Is Now Chinese.” Substack, January 11. https://substack.com/home/post/p-184141480 [January 30, 2026].

2 See: Zeyi Yang and Louise Matsakis. 2026. “Why Everyone Is Suddenly in a ‘Very Chinese Time’ in Their Lives.” WIRED, January 16 https://www.wired.com/story/made-in-china-chinese-time-of-my-life/ [January 30, 2026].

3 See: Li Yuan. 2026. “Why China Is Suddenly Obsessed With American Poverty.” The New York Times, January 13 https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/13/business/china-american-poverty.html [February 1, 2026].

4 See: The Economist. 2026. “China Obsesses over America’s “Kill Line.”” The Economist, January 12 https://www.economist.com/china/2026/01/12/china-obsesses-over-americas-kill-line [February 1, 2026].

5 See: Ma Junjie. 2025. “A ‘Loser’s Nation’ and the Abandoned Chinese Dream.” The Diplomat, September 4. https://thediplomat.com/2025/09/a-losers-nation-and-the-abandoned-chinese-dream/ [February 3, 2026].

6 See: Cole Henry Highhouse. 2022. “China Content on TikTok: The Influence of Social Media Videos on National Image.” Online Media and Global Communication 1 (4): 697–722.

6 See: Florian Schneider. 2021. “China’s Viral Villages: Digital Nationalism and the COVID-19 Crisis on Online Video-Sharing Platform Bilibili.” Communication And The Public 6 (1-4): 48-66.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Chapter Dive

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

A virtual Viagra for a pressured generation? The real story behind China’s latest viral app.

Published

1 month agoon

January 14, 2026

From censored joke to state-friendly app, ‘Are You Dead Yet?’ has traveled a long road before reaching the top of China’s paid app charts this week. While marketed as a tool for those living alone to check in with emergency contacts, the app’s viral success actually isn’t all about its features.

It is undoubtedly the most unexpected app to go viral in 2026, and the year has only just started. “Are You Dead?” or “Dead Yet?” (死了么, Sǐleme) is the name of the daily check-in app that surged to the No. 1 spot on Apple’s paid app chart in China on January 10–11, quickly becoming a widely discussed topic on Chinese social media. It has since become a top-searched topic on the Q&A platform Zhihu and beyond, and by now, you may even have noticed it appearing on your local news website.

For many Chinese who first encountered the app, its name caused unease. In China, casually invoking words associated with death is generally considered taboo, seen as causing bad luck. It was therefore especially noteworthy to see state media outlets covering the trend. The fact that the name plays on China’s popular food delivery platform Ele.me (饿了么, “Hungry Yet?”), a household name, may also have softened the linguistic sensitivity.

Beyond the name, attention soon shifted to the broader social undercurrents and collective anxieties reflected in the app’s sudden popularity.

🔹 “A More Reassuring Solo Living Experience”

Are You Dead Yet? is a basic app designed as a safety tool for people living alone, allowing them to “check in” with loved ones. The Chinese app has been available on Apple’s App Store since 2025 and currently costs 8 yuan (US$1.15) to download.

The app is very straightforward and does not require registration or login. Users simply enter their name and an emergency contact’s email address. Each day, they tap a button to virtually “check in.”

If a user fails to check in for two consecutive days, the system automatically sends an email notification to the designated emergency contact the following day, prompting them to check on the user’s safety.

The app was created by Guo Mengchu (郭孟初) and two of his Gen Z friends from Zhengzhou, all born after 1995. Together, they founded the company Moonlight Technology (月境技术服务有限公司) in March 2025, with a registered capital of 100,000 yuan (US$14,300). The app was reportedly developed in just a few weeks at a cost of approximately 1,000 yuan (around US$143).

In the text introducing the Dead Yet? app, the makers write that the app is specifically intended to “build seamless security protection for a more reassuring solo living experience” (“构建无感化安全防护,让独处生活更安心”).

🔹 The Rise of China’s Solo-Living Households

The number of solo households in China has skyrocketed over the past three decades. In the mid-1990s, only 5.9% of households in China were one-person households. By 2011, that number had nearly tripled from 19 million to 59 million, accounting for nearly 15% of China’s households.1,2 By now, the number is bigger than ever: single-person households account for over 25% of all family households.3

These roughly 125 million single-person households are partly the result of China’s rapidly aging society, along with its one-child policy. With longer life expectancies and record-low birth rates, more elderly people, especially widowed women, are living alone without their (grand)children.

China’s massive urban-rural migration, along with housing reforms that have adapted to solo-living preferences, has also contributed to the fact that China is now seeing more one-person households than ever before. By 2030, the number may exceed 150 million.

But other demographic shifts play an increasingly important role: Chinese adults are postponing marriage or not getting married at all, while divorce rates are rising. Over the past few years, Chinese authorities have introduced various measures to encourage marriage and childbirth, from relaxed registration rules to offering benefits, yet a definitive solution to combat China’s declining birth rates remains elusive.

🔹 A “Lonely Death”: Kodokushi in China

Especially for China’s post-90s generation, remaining unmarried and childless is often a personal choice. On apps like Xiaohongshu, you’ll find hundreds of posts about single lifestyles, embracing solitude (享受孤独感), and “anti-marriage ideology” (不婚主义). (A few years back, feminist online movements promoting such lifestyles actually saw a major crackdown.)

Although there are clear advantages to solo living—for both younger people and the elderly—there are also definite downsides. Chinese adults who live alone are more likely to feel lonely and less satisfied with their lives 4, especially in a social context that strongly prioritizes family.

Closely tied to this loneliness are concerns about dying alone.

In Japan, where this issue has drawn attention since the 1990s, there is a term for it: kodokushi (孤独死), pronounced in Chinese as gūdúsǐ. Over the years, several cases of people dying alone in their apartments have triggered broader social anxiety around this idea of a “lonely death.”

One case that received major attention in 2024 involved a 33-year-old woman from a small village in Ningxia who died alone in her studio apartment in Xianyang. She had been studying for civil service exams and relied on family support for rent and food. Her body was not discovered for a long time, and by the time it was found, it had decomposed to the point of being unrecognizable.

Another case occurred in Shanghai in 2025. When a 46-year-old woman who lived alone passed away, the neighborhood committee was unable to locate any heirs or anyone to handle her posthumous affairs. The story prompted media coverage on how such situations are dealt with, but it drew particular attention because cases like this had previously been rare, stirring a sense of broader social unease.

🔹 The Sensitive Origins of “Dead Yet?”

Knowing all this, is there actually a practical need for an app like Dead Yet? in China? Not really.

China has a thriving online environment, and its most popular social media apps are used daily by people of all ages and backgrounds, across urban and rural areas alike. There are already countless ways to stay in touch. WeChat alone has 1.37 billion monthly active users. In theory (even for seniors) sending a simple thumbs-up emoji to an emergency contact would be just as easy as clocking in to the Dead Yet? app.

The app’s viral success, then, is not really about its functionality. Nor is it primarily about elderly people fearing a lonesome death. Instead, it speaks to the dark humor of younger adults who feel overwhelmed by pressure, social anxiety, and a pervasive sense of being unseen—so much so that they half-jokingly wonder whether anyone would even notice if they collapsed amid demanding work cultures and family expectations.

And this idea is not new.

After some online digging, I found that the app’s name had already gone viral more than two years earlier.

That earlier viral moment began with a Zhihu post titled “If you don’t get married and don’t have children, what happens if you die at home in old age?” (“不结婚不生孩子,老后死在家中怎么办”). Among the 1,595 replies, the top commenter, Xue Wen Feng Luo (雪吻枫落), whose response received 8,007 likes, wrote:

💬 “You could develop an app called “Dead Yet?” (死了么). One click to have someone come collect the body and handle the funeral arrangements.”

The original post that started it all. That humorous comment was the initial play on words linked to food delivery app Eleme (饿了么).

Two days later, on October 8, 2023, comedy creator Li Songyu (李松宇, @摆货小天才), also part of the post-90s generation, released a video responding to the comment.

In it, he presented a mock version of the app on his phone: its logo a small ghost vaguely resembling the Ele.me icon, and its interface showing some similarities to ride-hailing apps like Uber or Didi.

In the video, Li says:

🗯️ “Are You Dead Yet?’ I’ve already designed the app for you. (…) The app is linked to your smart bracelet. Once it fails to detect the user’s pulse, someone will immediately come to collect the body. Humanized service. You can choose your preferred helper for your final crossing, personalize the background music for cremation and burial, and even set the furnace temperature so you can enter the oven with peace of mind. Big-data matching is used to connect people who might have known each other in life, followed by AI-assisted cemetery matching for the afterlife traffic ecosystem—you’ll never feel alone again. After burial, all content on your phone is automatically formatted to protect user privacy and eliminate worries about what comes after. There’s a seven-day no-reason refund, almost zero negative reviews, and even an ‘Afterlife Package’ with installment payments. Invite friends to visit the grave and have them help repay the debt. And if not everything turns to ashes properly, or if you’re dissatisfied with the shape of the remains, you can invite friends to burn them again and get the second headstone at half price! How about that? Tempted?”

The original “Sileme” or “Dead Yet” app idea, October 2023.

The video went viral, drew media coverage (one report called the concept and design of the “Are You Dead?” app “unprecedented”), and sparked widespread discussion. Although viewers clearly understood that the idea—one click and someone arrives to collect the body and arrange the funeral—was a joke, it nevertheless struck a chord.

Many saw the video as a glimpse into China’s future, arguing that with extremely low birth rates and a rapidly aging society, such business ideas might one day become feasible. Some people pointed to Japan’s growing problem of elderly people dying alone, suggesting that China may come to face similar challenges. At the same time, it also sparked concerns about increasing social isolation.

Despite its popularity, both the video and the trending hashtag “Dead Yet App” (#死了么APP#) were taken offline. A comedy podcast episode discussing the concept—“Did Someone Really Create the ‘Dead Yet’ App?” (真的有人做出了“死了么”APP?), released on October 10, 2023 by host Liuliu (主播六六)—was also removed.

According to Li Songyu himself, the video went offline within 48 hours “for reasons beyond one’s control” (“出于不可抗因素”), a phrase often used to avoid explicitly referring to top-down decisions or censorship.

It is not hard to guess why the darkly humorous Dead Yet? concept disappeared. And it wasn’t only because of crude jokes or the sensitivities surrounding death.

The video appeared less than a year after the end of China’s stringent zero-Covid policies, which had been preceded by protests. In both early and late 2023, Covid infections were widespread and hospitals were overcrowded. It was therefore a particularly sensitive moment to joke about bodies, afterlife logistics, and people being “taken away.”

Moreover, 2023 was a year in which state media strongly emphasized “positive energy,” promoting stories of heroism, self-sacrifice, and resilience in the face of hardship. It was not a time to dwell on death, and certainly not through humor.

🔹 Why a Censored Idea Became a ‘State-Friendly’ App

In 2025, things looked very different. Just weeks after the current Dead Yet? app was developed, it was released on the App Store on June 10, 2025. Not only was its name identical to the app “introduced” by Li in 2023, but its logo was also a clear lookalike.

The 2023 logo and 2025 “Dead Yet?” logo’s.

Although Li Songyu published a video this week explaining that he and his team were the original creators of the Dead Yet? concept and that they had planned to develop a real app before the idea was censored (without ever registering the trademark), app creator Guo Mengchu has simply stated that the inspiration for their app came “from the internet.”

In the same interview, Guo also emphasized that the app’s sudden rise was entirely organic, with the whole process of “going viral,” from ordinary users to content creators to mainstream media, taking about a day and a half.5

However, the app’s actual track record suggests a much bumpier journey.6 Since its launch, it has been taken down once and was reportedly removed from the App Store rankings three times. Such removals commonly occur due to suspected artificial download inflation, ranking manipulation, or other compliance-related issues.

After the most recent delisting on December 15, 2025, the app returned to the App Store on December 25—and only then did it finally have its breakthrough moment.

📌 Looking at how online discussions unfolded around the app, it becomes clear that, just as in 2023, the idea of relying on technology to ensure someone will notice if you die strongly resonates with people. Many users also seem to have downloaded it simply as a quirky app to try out. Once curiosity set in, the snowball quickly started rolling.

📌 But Chinese state media have also played a significant role in amplifying the story. Outlets ranging from Xinhua (新华) and China Daily (中国日报) to Global Times (环球时报) have all reported on the app’s rise and subsequent developments.

🔎 Why was Li Songyu’s Dead Yet? app idea not allowed to remain online, while Guo’s version has been able to thrive? The difference lies not only in timing, but also in tone. Li’s original concept leaned more clearly toward implicit social critique & satire. Guo’s app, by contrast, has been framed — and received — with far less overt sarcasm. While many netizens may still interpret it as dark humor, within official narratives it aligns more neatly with the family-focused social discourse, and perhaps even functions as an implicit warning: if you end up alone, you may literally need an app to ensure you do not die unnoticed.

In this way, the young creators of the new app are, perhaps inadvertently, contributing to an ongoing official effort in media discourse and local initiatives to encourage Chinese single adults to settle down and start a family. For them, however, it is a business opportunity: more than sixty investors have already expressed interest in the app.

Funnily enough, many single men and women actually hope to use the app to support their lifestyle. When, during the upcoming Chinese New Year, parents start nagging about when they will settle down, and warn that they might otherwise die alone, they can now reply that they’ve already got an app for that.

🔹 What’s in a Name?

Over the past few days, much of the discussion has centered on the app’s name, which is what drew attention to it in the first place. As interest in the app surged, fueled by international media coverage, criticism of the name also grew. Some found it too blunt, while public commentators such as Hu Xijin openly suggested that it be changed.

Considering that the mention of death itself carries online sensitivities in China, it’s possible that there’s been some criticism from internet regulators, and the Ele.me platform also might not be too pleased with the name’s resemblance.

Whatever the exact reasons, the app’s creators announced on January 13 that they would abandon the original name and rebrand the app as its international name ‘Demumu’ (De derived from death, the rest intentionally sounds like ‘Labubu’).

This marked a notable shift in stance: just two days earlier, one of the app’s creators had stated that they had not received any formal requests from authorities to change the name and had shown no apparent intention of doing so.

Most commenters felt that without the original name, the app doesn’t make sense. “As young people, we don’t care so much about taboo words,” one commenter wrote: “Without this name, the app’s hype will be over.”

On January 14, the creators then made another U-turn and invited app users to think of a new name themselves, rewarding the first user who proposes the chosen name with a 666 yuan reward ($95).

The naming hurdles suggest the makers are quite overwhelmed by all the attention. At the same time, dozens of competing apps have already appeared. One of them, launched just a day after Are You Dead Yet? went viral, is “Are You Still Alive?” (活了么), which offers similar basic functions but is free.

This new wave of similar apps has also led more people to wonder how effective these tools really are once the quirkiness wears off. One Weibo blogger wrote:

💬 “I really don’t understand why this app went viral. You can only check in daily, and you need to miss two consecutive check-in days for the emergency contact to be alerted. That means, if something actually happens, someone will only come after three days!! You’ll be rotting away in your home!!”

Others also suggested that it is clear the app was designed by younger people—the elderly users who might need it most would likely forget to check in on a daily basis.

🔹 Why “Dead Yet?” Is Like Viagra for a Pressured Generation

Amid the flood of Chinese media coverage, one commentary by the Chinese media platform Yicai7 stands out for pinpointing what truly lies behind the app’s popularity.

The author of the piece “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Dead Yet’ App” (in Chinese) argues that the app did not win users over because of its practical utility. Its main users are young people for whom premature death is an extremely low-probability event. They are clearly not downloading the app because they genuinely fear that “no one would know if they died,” nor are they likely to check in daily for such a tiny risk.

Since the app is clearly being embraced by users that do not belong to the actual target group, it must be providing some unexpected value.

💊 The author compares this unplanned function of the app to how Viagra was originally developed to treat heart disease. In this case, app users say that interacting with Dead Yet? feels like a lighthearted joke shared between close friends, offering a sense of social empathy and emotional release in a way that does not feel pressured.

Because the pressure—that’s the problem. Yicai describes just how multidimensional the pressures facing many young adults in China today can be: there is the economic challenge of the never-ending rat race dubbed “involution” along with uncertainty in the job market; there’s the “996” extreme work culture across various industries, leaving little room for private life; traditional family expectations that clash with housing and childcare costs that many find unattainable; and the world of WeChat and other social media, which can further intensify peer pressure and anxiety.

Of course, a lot has been written about these issues through the years. But do people really get it?

According to Yicai, there’s not enough understanding or support for the kinds of challenges young people face in China today. Even worse, older generations’ own past experiences often impose additional burdens on younger people, who keep running up against traditional notions while receiving inadequate support in areas such as education, employment, housing, marriage, family life, and even healthcare.

The author describes the unexpected viral success of Dead Yet? as a mirror with a message:

💬 “The viral popularity of ‘Are You Dead?’ seems like a darkly humorous social metaphor, reminding us to pay attention to the living conditions and inner worlds of today’s youth. For the young people downloading the app, what they need clearly isn’t a functional safety application, it’s a signal that what they really need is to be seen and to be understood—a warm embrace from society.”

Will the Dead Yet? app survive its name change? Is there a future for Demumu, or whatever it will end up being called? As it is now—the basic app with check-in and email or SMS functions—it might not keep thriving beyond the hype. If it doesn’t, it has at least already fulfilled an important function: showing us that in a highly digitalized, stressful, and often isolating society where AI and social media play an increasingly major role, many people yearn for the simple reassurance of being noticed, mixed with a shared delight in dark humor. Just a little light to shine on us, to remind us that we’re not dead yet.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Thanks to Ruixin Zhang & Miranda Barnes for additional research

1 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2013. “Living Alone in China: Historical Trends, Spatial Distribution, and Determinants.”

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Living-Alone-in-China-%3A-Historical-trend-%2C-Spatial-Yeung-Cheung/8df22ddeb54258d893ad4702124066b241bbdf8d.

2 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2015. “Temporal-Spatial Patterns of One-Person Households in China, 1982–2005.” Demographic Research 32: 1103–1134.

3 Li Jinlei (李金磊). 2022. “China’s One-Person Households Exceed 125 Million: Why Are More People Living Alone?”[中国新观察|中国一人户数量超1.25亿!独居者为何越来越多?]. China News Service (中国新闻网), January 14, 2022. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cj/2022/01-14/9652147.shtml (accessed January 13, 2026).

4 Danan Gu, Qiushi Feng, and Wei-Jun Jean Yeung. 2019. “Reciprocal Dynamics of Solo Living and Health Among Older Adults in Contemporary China.”

The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 74 (8): 1441–1452. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby140.

5 Wang Fang (王方). 2026. “‘How We Went Viral: The Founder of the ‘Dead Yet?’ App Speaks Out’” [‘死了么’创始人亲述:我们是如何爆红的]. Pencil Way (铅笔道), interview with Guo (郭先生), published via 36Kr (36氪), January 13, 2026. https://www.36kr.com/p/3637294130922754 (accessed January 13, 2026).

6 Lü Qian (吕倩). 2026. “‘Am I Dead?’ App Price Raised from 1 Yuan to 8 Yuan, Previously Removed from Apple App Store Rankings Multiple Times”

[‘死了么从一元涨至八元,曾被苹果AppStore多次清榜’]. Diyi Caijing (第一财经), January 11, 2026. https://www.yicai.com/news/102997938.html (accessed January 14, 2026).

7 First Financial/Yicai (第一财经). 2026. “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Am I Dead?’ App: Young People Need a Hug” [‘死了么爆火背后,年轻人需要一个拥抱’]. Official account article, January 12, 2026. https://www.toutiao.com/article/7594671238464569899/ (accessed January 14, 2026).

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: Takaichi’s Win, Olympic Tensions, and “Tapping Out”

Spending the Day in China’s Wartime Capital

Chinamaxxing and the “Kill Line”: Why Two Viral Trends Took Off in the US and China

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

Popular Reads

-

Chapter Dive7 months ago

Chapter Dive7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

Chapter Dive9 months ago

Chapter Dive9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

Chapter Dive10 months ago

Chapter Dive10 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West