China Arts & Entertainment

Chunwan 2022: The CMG Spring Festival Gala Liveblog by What’s on Weibo

Published

4 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT

As we are leaving the Year of the Ox and entering Year of the Tiger, it’s time for the 40th edition of the Spring Festival Gala! Watch the Gala together with What’s on Weibo here and follow our liveblog to keep up with what’s happening on screen and on social media (this liveblog has now closed, read the overview below!) [Premium content]

Another year has flown by and despite many changes, we can always count on China’s annual Spring Festival Gala. This 40th edition of the festival is the third one to take place in the Covid era.

The Gala will be broadcast on TV and live-streamed via various channels on January 31st, 20.00 pm China Standard Time. So turn on your TV and tune into CCTV, live stream from Weibo, watch on YouTube, or head to the CCTV website. We will be live-blogging on this page here and you can scroll & watch at the same time from this page.

Very Brief Introduction to the Spring Festival Gala

China’s Spring Festival Gala (中国中央电视台春节联欢晚会), commonly abbreviated to chūnwǎn (春晚), is the annual TV gala celebrating the start of the new year. Broadcasted since 1983, it is not just the biggest live televised event in China, it is even among the most-watched shows in the world. The show reached a record 1.27 billion viewers around the globe in 2021.

Previously known as the ‘CCTV Gala,’ it is officially presented as the ‘CMG Spring Festival Gala’ since 2020: it is hosted by China Media Group (CMG), the predominant state media company founded in 2018 that holds China Central Television, China National Radio, and China Radio International.

The Gala is an important Chinese media moment and significant cultural event organized and produced by the state-run broadcaster, overseen by the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA), and aired across dozens of channels. It shows the very best of China’s mainstream entertainment and Party propaganda and is a mix of traditional culture, (digital) commerce, and politics. It is an opportunity for the Party to communicate official ideology, it is also a chance to present the nation’s top performers.1

Since recent years, it has also become a platform to showcase China’s innovative digital technologies. In 2015 the show first featured the exchange of virtual hongbao, red envelopes with money, which WeChat users could obtain while shaking their phones during specific moments in the show. Such marketing strategies have drawn in much younger viewer audiences than before. In 2021, the Gala explicitly presented itself as a “tech innovation event” by using 8K ultra high-tech definition video and AI+VR studio technologies and super high definition cloud communication technology to coordinate performances on stage.

The show lasts a total of four hours, from 8pm to 1am Beijing time, and usually has around 30-40 different acts, from dance to singing and acrobatics. The acts that are both most-loved and most-dreaded are the comic sketches (小品) and crosstalk (相声); they are usually the funniest, but also convey the most political messages.

As viewer ratings of the Gala in the 21st century have skyrocketed, so has the critique on the show – which seems to be growing year on year. According to many viewers, the spectacle generally is often “way too political” with its display of communist nostalgia, including the performance of different revolutionary songs such as “Without the Communist Party, There is No New China” (没有共产党就没有新中国).

For this same reason, the sentence “There’ll never be a worst, just worse than last year” (“央视春晚,没有最烂,只有更烂”) has become a well-known idiom connected to the Gala.

If you want to know more about the previous editions, we also live-blogged

– 2021: The Chunwan Liveblog: Watching the 2021 CMG Spring Festival Gala

– 2020: CCTV New Year’s Gala 2020

– 2019: The CCTV Spring Festival Gala 2019 Live Blog

– 2018: CCTV Spring Festival Gala 2018 (Live Blog)

– 2017: CCTV New Year’s Gala 2017 Live Blog

– 2016: CCTV’s New Year’s Gala 2016 Liveblog

Liveblog CMG Spring Festival Gala 2022

Underneath here you will see our liveblog being updated. Leave the page open and you’ll see the new posts coming in, there should be a ‘ping’ too with every update.

Update: this liveblog is now closed, check below for an overview of the entire show.

——–

The original liveblog was done via a third-party app. The original texts and images are copied below for reference. If there are links to particular segments of the show, they have been added later. The timestamp (in Beijing time) refers to the last moment that post was updated.

Want to directly check out some Spring Festival Gala highlights on YouTube?

We recommend:

The ‘painting’ dance: ‘Only This Green (只此青绿)

The dancing elephant song: ‘The Herd Returns With Spring’ (万象回春)

Creative music, dance, poetry, and painting: “Reminiscence of the South” (忆江南)

Tai Chi up in the sky: ‘Flowing Water’ (行云流水)

The space-themed children performance: ‘Star Dreams’ (星星梦)

——–

What can we expect?

Jan 31 19:30

It’s almost time for the 40th edition of the Spring Festival Gala to begin. The fifth and final rehearsal of the entire event took place on January 29th. Even if something goes wrong tonight, the tape of the official rehearsal runs together with the live broadcast, so that in the event of a problem or disruption, the producers can seamlessly switch to the taped version without TV audiences noticing anything.

The Spring Festival Gala usually always focuses on the themes that matter to Chinese authorities, as the event is an important moment to communicate official ideology.

The themes and topics that mattered last year were China’s battle against COVID19, the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, China’s eradication of poverty, China’s Space Program, and the upcoming Winter Olympics.

This year most of these themes will probably again also play an important role this year, together with rural revitalization and China’s unity, with a special focus on Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Also, we’re pretty sure that Olympic mascots Bing Duan Duan (“Bing Dwen Dwen”) and Xue Rong Rong (“Shuey Rhon Rhon”) will show up.

——–

Less Focus on Celebrity Culture

Jan 31 19:35

After a year of celebrities being canceled and crackdowns shaking the Chinese entertainment industry to the core, this year’s Spring Festival Gala will be less focused on popular idols of the internet era and more focused on performing art talents and national heroes.

Chinese state outlet Global Times stressed the idea that those performing in the Chinese New Year Gala should “act as a role model to viewers.”

Many of the people who have an impeccable track record are the older performing artists (those who never had to deal with the social media audiences), so the average age of the artists tonight might be a bit higher up the age ladder than usual.

——–

Most Anticipated Acts?

Jan 31 19:50

One of the most anticipated acts for tonight is the dance play “Only This Green” (只此青绿) inspired by the famous handscroll “One Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains.” In this performance, choreography twin stars Zhou Liya and Han Zhen will highlight the aesthetics of traditional Chinese painting.

The performance of the official Winter Olympics theme song is also attracting some attention.

Overall, the schedule of tonight’s show is looking fairly traditional, although there will be plenty of tech on display too; a 720-degree dome made of LED screens is set up for an immersive viewing experience, and the latest technology like AR, XR, and 8K will also be used.

——–

Liu Zhen: Chief Director

Jan 31 19:57

This year’s director of the Spring Festival Gala is Liu Zhen (刘真), who is the Deputy Director of the CCTV arts channel. He is known for previously directing the 2009 anniversary night of the Great Sichuan earthquake and he also directed the 2019 Spring Festival Gala themed around “New China.”

Noteworthy enough, it seems that this year’s Gala is only broadcasted from CCTV 1 Beijing Studio. Usually, there are also three or four other sub venues in other parts of China. Perhaps the Covid19 situation has been a contributing factor to deciding to let this year’s show only take place in one location.

——–

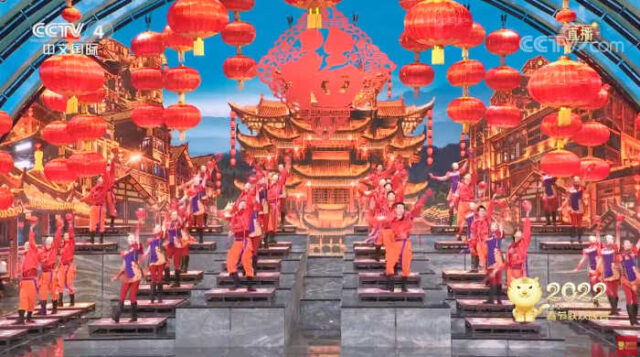

We’re starting!

Jan 31 20:05

In this opening act, Happy and Auspicious Year (欢乐吉祥年), three major Wuhan art groups are on stage together with many familiar faces, including the 87-year old actress Tao Yuling, we just saw Chinese director Zhang Yimou and acclaimed actor Ge You appearing in the intro, and there are many others together with some veteran performers who are being honored on stage today.

——–

Tonight’s hosts

Jan 31 20:06

These are tonight’s hosts:

Ren Luyu (任鲁豫, 1978): Ren Luyu is a famous Chinese television host from Henan who is a very familiar face for viewers. He presented the Gala five times since 2010.

Li Sisi (李思思, 1986): Li Sisi is a Chinese television host and media personality who is actually most known for her role as host of the Gala since 2012. This is the fifth time Li Sisi is presenting the Gala. She used to be the youngest host, but this year, Ma Fanshu is taking her place as the youngest host.

Nëghmet Raxman (尼格买, 1983): Together with Ren Luyu, Raxman is known as one of the veteran Gala hosts of the past decade. This is the seventh time for him to present the event since 2015. Nëghmet Raxman is a Chinese television host, born and raised in Ürümqi, Xinjiang.

Sa Beining (撒贝宁, 1976): Also known as Benny Sa, SA Beining previously presented the Gala in 2012, 2013, 2015, and 2016. He is a Chinese television host known for his work for CCTV.

Ma Fanshu (马凡舒, 1993): Ma Fanshu is the youngest and newest host in this year’s Gala. She is a sports program host who has also been called “the most beautiful host of CCTV.”

It’s noteworthy that renowned CCTV host Zhu Jun still has not returned to the Gala. The presenter was accused of sexually assaulting an intern in 2018 and hasn’t been a host at the Gala since. Although the internet lost the sexual harassment lawsuit against Zhu Jun, he still hasn’t reappeared.

——–

Sense of the Times 时代感

Jan 31 20:10

This song is performed by the Chinese actor and singer Deng Chao (邓超) together with China’s ‘Supergirl’ Li Yuchun (李宇春) and Yi Yang Qianxi (Jackson Yee), the youngest member of the Chinese boy band TFBoys and super popular solo artist.

On stage, we also see dancer Zhang Yin (张引) together with various dance troupes.

Tonight we’ll see other members of the TFBoys come up in other acts as solo artists rather than as a group.

Link to this performance here.

——–

Skit: Father and Son

Jan 31 20:15

This is the first sketch comedy or short play of the night, called xiaopin 小品 in Chinese. Traditionally, the xiaopin is the best-received type of performance of the Gala for evoking laughter among the audiences. The various xiaopin shows are filled with puns, funny lines, and plot twists to entertain the viewers.

Over recent years, these comic acts performed during the Spring Festival Gala have come to center more on social issues such as environmental protection, corruption, social morals, migrant workers, and family affairs – including those concerning love and marriage. These are not always appreciated as much by viewers.

Meanwhile, on Chinese social media, some netizens are wondering who this kid is who was on stage earlier because he seemed a bit uncomfortable and awkward. But wouldn’t you too?! Over a billion people are watching this show!

Link to this performance here.

——–

The ‘Awkward Kid’

Jan 31 20:20

Look son, you’re a meme now!

——–

Pressured by the Parents

Jan 31 20:25

Inevitably, this skit touches upon the issue of Chinese parents pressuring their kids to settle down and have kids. This is already leading to online discussions as viewers often think the Gala has skits that are insulting to women or just embarrassing. In this case, the grandpa can’t wait for a grandkid, he even thinks his future grandchild is already calling him from the womb!

Link to this performance here.

——–

The Herd Returns With Spring

Jan 31 20:36

After the night’s first public announcement video – which was actually very well made with the tiger jumping through all the scenes -, we are now at the next segment. This is a musical skit (音乐短剧) focused on how nature blossoms with the return of spring (万象回春). It is performed by Chinese mainland singers Sha Baoliang (沙宝亮) and Wang Li (王莉) together with dancer and singer Liu Jia (刘迦).

The highlight of this act is the dancing elephants. They’re not real, obviously.

Last year, a herd of wild Asian elephants wandered hundreds of miles across southern China. They became a top trending topic on Chinese social media as netizens followed their journey. In September 2021, the elephants returned home after covering a total distance of 1,300 km.

Before tonight’s show, a creator already highlighted the elephants in the countdown program.

Link to this performance here.

——–

Spring Breeze

Jan 31 20:38

Chinese soprano Yin Xiumei (殷秀梅) and contemporary opera singer Yan Weiwen (阎维文) perform the song Ten Thousand Miles of Spring Wind (春风十万里), which was previously performed at the 2020 Gala by Zhang Ye (张也) and Liu Tao (刘涛).

Link to this performance here.

——–

21 Weibo Accounts Suspended For ‘Ruining The Holiday Spirits’ During Lunar New Year

Jan 31 20:40

We’re seeing loads of criticism on the Gala already. Online criticism and making fun of the Gala is a big part of the ‘Chunwan Experience’ ever since the social media era. But Weibo censors might be stricter this year.

On January 22, Weibo issued an indirect warning to netizens criticizing the festive annual Chinese New Year Galas by suspending 21 Weibo users spreading negativity regarding broadcasted festival programs and their performances.

According to Weibo Management (@微博管理员), there are individual netizens who are using televised Lunar New Year celebrations to condemn and slander Chinese performers and Chinese media. In doing so, they allegedly “deliberately destruct the warm and peaceful holiday spirit.”

“In times of pandemic, the Spring Festival needs positivity and warmth,” Weibo Management stated.

——–

Comical Sketch: To Return or Not?

Jan 31 20:45

This is the sixth time for Chinese comedian Shen Teng (沈腾) and Ma Li (马丽) to be on stage together at the Spring Festival Gala. Besides that, you also might know them because Shen Teng, one of China’s top comedian actors, and the famous Ma also played together in the 2015 hit movie Goodbye Mr. Loser (夏洛特烦恼).

On stage with them are Chang Yuan (常远), Ai Lun 艾伦, Wang Chengsi (王成思) and Xu Wenhe (许文赫).

This act is about people who have the means to repay debts they owe but choose not to, also referred to as 老赖 (laolai). This guy is so cheap he even offers a drink of water from the heating system.

By the way, did you know you can even watch the Gala from WeChat? It seems there are more ways and channels to watch every year. The Gala already reached a record 1.27 billion viewers last year.

Link to this performance here.

——–

Heads Up! Only This Green (只此青绿)

Jan 31 21:04

This is a much-anticipated dance performance by Chinese star dancer Meng Qingyang (孟庆旸) together with the China Oriental Performing Arts Group. Meng also performed the dance Jasmine in last year’s Gala.

“Only This Green” (只此青绿) is inspired by the famous handscroll “One Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains.” In this performance, choreography twin stars Zhou Liya and Han Zhen will highlight the aesthetics of traditional Chinese painting.

The 11.9-meter (39 ft)-long scroll A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains by Wang Ximeng comes from the Song Dynasty and it has been described as one of the greatest works of Chinese art. The painting is in the permanent collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing.

Link to this performance here.

——–

Tai Chi: “Flowing Water”

Jan 31 21:10

Chinese Olympic athlete Yang Shunhong (杨顺洪), Tai Chi World Champion Liang Bifeng (梁壁荧) and Tai Chi master Yang Dezhan (杨德战) were just featured in this impressive Tai Chi performance recorded on dazzling heights in Shanghai. (Correction > recorded from the three highest buildings in Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Chongqing!)

Link to video: ‘Flowing Water’ (行云流水)

——–

Chunwan Shopping

Jan 31 21:21

Over recent years, it’s become more common for e-commerce sellers to immediately jump in on the hype of what performers are wearing to sell the same or similar clothes and accessories online. In this way, viewers can watch the show while also eating and shopping, and chatting on social media at the same time!

——–

喜上加喜

Jan 31 21:23

In this comic sketch, we see Chinese comedian actress and film director Jia Ling together with award-winning actress Zhang Xiaofei. These two also worked together in the super popular 2021 movie ‘Hi, Mom‘. This time they are on stage as a mother-in-law and daughter-in-law. Since they’re both very popular, many Weibo users also said they were looking forward to seeing this sketch – especially because there was a scene in which Jia Ling, who played Zhang’s daughter in the movie, said: “Next life, let me be your mother.”

Meanwhile, some on social media are wondering if Jia is wearing the same outfit every year.

Link to this performance here.

——–

Uhm…

Jan 31 21:29

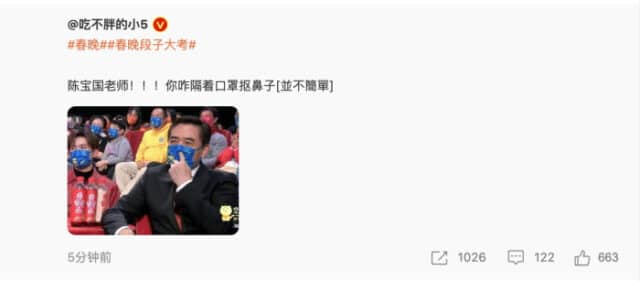

Some very quick viewers were able to capture Chinese actor Chen Baoguo (陈宝国) picking his nose with his mask on while sitting in the audience.

By the way, this is the second year the audience is wearing a face mask. In 2020, when Wuhan was first facing the Covid19 outbreak, the audience was not wearing face masks yet. 2021 was the first year.

——–

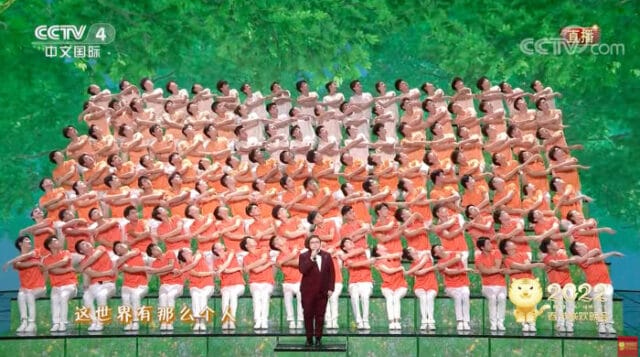

Here’s Han Hong Again

Jan 31 21:33

Singer Han Hong (1971) is one of China’s most famous pop singers and she is a regular at the Spring Festival Gala. For decades, the singer of mixed Tibetan and Han ethnicity was a member of a performing arts troupe within the People’s Liberation Army.

Tonight, she is singing the song So Many People in This World (这世界那么多人). She seemed to have some tears streaming down her face during her performance.

——–

Peking Opera

Jan 31 21:45

Every year you’ll see a Peking Opera act passing by during the Gala. This year, it is a mix of martial art acts together with singing. The performers are from all generations, from those born in the 1930s to those born in the early 2000s.

Link to this performance here.

——–

About that Sweater..

Jan 31 21:47

The sweater worn in the ‘debt dodger’ comic skit earlier tonight might have looked cheap, it’s actually $260! Gala viewers who liked the sweater can buy it online straight away.

——–

Grabbing Red Envelopes with JD

Jan 31 21:48

After the Gala partnered with Tencent, Kuaishou, and Baidu in previous years, they’ve now partnered up with e-commerce giant JD.com. Throughout the show, you’ll see various ‘media moments’ during which viewers can ‘catch’ red envelopes.

Actually, the Gala became especially linked to social media it first featured this kind of exchange of ‘hongbao’, red envelopes with money, which is a Chinese New Year’s tradition. In 2015, for the first time, viewers were able to receive virtual ‘hongbao’ as part of a cooperation between CCTV and WeChat. WeChat users shook their phones 11 billion times that night in order to ‘grab’ the money. These kinds of campaigns drew in much more young viewers – the Gala was previously viewed as something for older audiences – although it still might be, social media has helped get the younger viewers involved, too.

——–

“Sending Out Red Envelopes”

Jan 31 21:57

This is another comical sketch, titled Sending Out Red Envelopes (发红包) featuring some well-known comedians including Jia Bing.

This skit is another one focused on money: “You’d almost think that the director still needs to get his money back from someone,” some Weibo users are joking, since money seems to come up a lot as a theme in tonight’s comedy.

——–

Happy Vibes

Jan 31 22:09

Next up, there are some happy vibes with Da Zhangwei (大张伟) and Wang Mian (王勉) in this “music talk show” (“音乐脱口秀”) segment.

You might know Da Zhangwei as ‘Wowkie Zhang’ from the Sunshine Rainbow White Pony song. Attention was drawn to the song in the West when internet users thought that the chorus of the song, where Wowkie Zhang repeats the lyrics “nèi nèi ge nèi nèi nèi ge nèi ge nèi nèi,” was racist. But ‘nèi ge‘ is actually a filler word in Chinese (like ‘like’).

Link to this performance here.

——–

Magic Act

Jan 31 22:21

Usually, you’d expect magic performances to come a bit later in the show, but here we are with Chinese magician Daly Tang (邓男子). We’re halfway through the show.

This act is not received well on social media, with many saying this can’t even be called magic. Chinese actress being used as a ‘prop’ for the act is trending at this time.

Link to this performance here.

——–

乳虎啸春

Jan 31 22:25

There are martial arts at the festival every year, but this performance is a bit special since it combines comedy and martial arts and also is performed by many younger performers from the Henan Shaolin Tugou School of Martial Arts.

It is also a special performance because it combines martial arts with humor, whereas these kinds of performances are usually more serious.

According to one of the coaches of the children, the students practiced their facial expressions in the mirror every day as part of their homework. They also looked at film and television materials to learn from.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

“Happy Dialect”

Jan 31 22:39

This ‘crosstalk’ performance features xiangsheng actors Jiang Kun and Dai Zhicheng. Xiangsheng (相声) or crosstalk is a traditional Chinese comedic performance that involves a dialogue between two performers, using rich language and many puns.

Meanwhile, presenter Sa Beining is going viral for his peculiar role in the magic act.

Link to this performance here.

——–

“Star Dreams”

Jan 31 22:45

Every year, there’s always one song dedicated to children and it’s often all over the place. In the past, we’ve seen dancing panda’s and dogs, flowers, and even swinging broccoli on stage. Here we see the Air Force Blue Sky Children’s Art Troupe on stage together with Zhao Yixi (赵芸熙) in this beautiful space-themed performance.

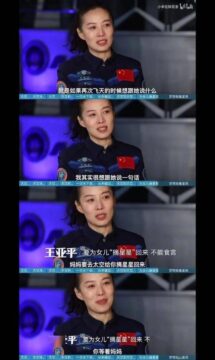

The kids’ performance “Star Dreams” also contained a special surprise: the little girl showing up at the end is actually the little daughter of female Chinese astronaut Wang Yaping, who is now on the 6-month Shenzhou-13 mission. She asked her mum to bring her back a star.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Yunnan Group Dance 摆出一个春天

Jan 31 22:48

This performance showcases the traditional folk dances from Lancang Lahu Autonomous County, located in the southwestern part of Yunnan province (not too far from the Myanmar border).

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

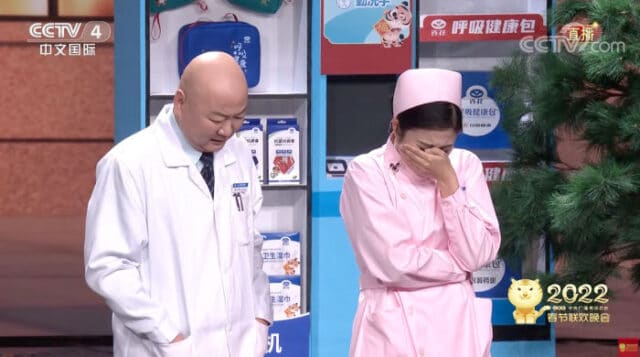

“Rest Area” Outside of the Hospital

Jan 31 23:00

Another comical skit, titled ‘Rest Area Story’ (休息区的故事), is performed by Guo Donglin (郭冬临), Shao Feng (邵峰), Han Yunyun (韩云云), Huang Yang (黄杨), Jiang Lilin (姜力琳), Zhang Dabao (张大宝).

Guo Donglin is notable for performing xiangsheng and sketch comedy and has appeared at the Gala for many years.

In this performance, we see a couple, who are both working on the frontlines of the epidemic, arguing together.

"Mask-wearing me when I say hi to my friends but they don't recognize me" pic.twitter.com/JmJiZpuWwT

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) January 31, 2022

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Sanxingdui Relics Ceremony and Dance

Jan 31 23:14

Chinese director Zhang Guoli is coming on stage now for this special ceremony that is all about the relics that were unearthed in southwest China earlier in 2021. A gold mask dating back over 3,000 years was among hundreds of relics uncovered from a series of sacrificial pits in southwest China. The finds were made at Sanxingdui, a 4.6-square-mile archeological site outside Chengdu.

Zhu Fengwei (朱凤伟) and Wang Xi (王西) perform this creative dance performance titled Golden Mask, of course referring to the special artifact found at Sanxingdui.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

ShaLaLaLa Song

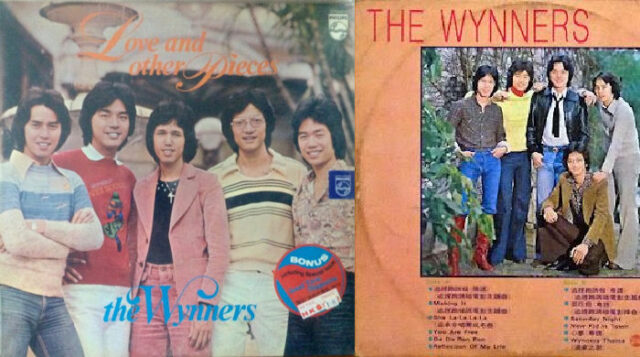

Jan 31 23:17

Canto-pop is here! The singers performing this Shalalala song are all established names from Hong Kong. There’s Alan Tan, a big name in the Cantopop scene of the 1980s. There’s Kenny Bee who has been in the entertainment industry for at least three decades. We also see Bennett Pang, Anthony Chan, and Bingo Tso.

Together, these artists once were in the Hong Kong English pop band The Wynners, which became one of the most popular teen idol groups in Hong Kong during the 1970s.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

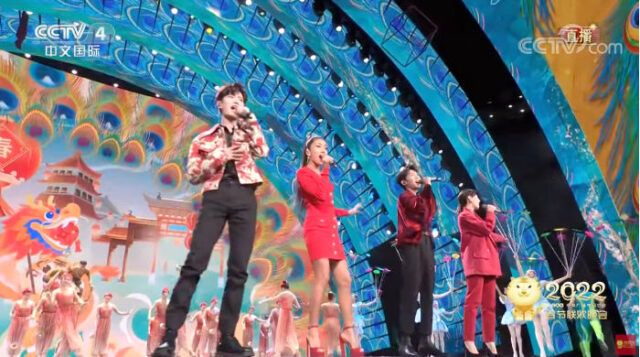

True Love Dance

Jan 31 23:22

The China Acrobatic Troupe is on stage to perform the True Love Dance (真爱起舞). Singing are Chinese actors and singers Ren Jialun (任嘉伦), Roy Wang (王源), Victoria Song (宋茜), and Jike Junyi (吉克隽逸).

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Another Xiangsheng

Jan 31 23:33

This xiangsheng or ‘crosstalk’ performance is by Lu Xin and Yu Hao. Crosstalk usually involves two actors with one being the “joker” and the other being the “teaser,” it is all about word jokes and playing with rhythm and language.

Meanwhile, on Weibo, many netizens are complaining that they don’t find the language performances as funny as before and that they are missing the older performers they grew up seeing on tv.

——–

You are the Gift of My Life

Jan 31 23:38

This song is sung by the renowned Chinese singer and songwriter Liu Huan (刘欢), who is famous for his work within China’s pop music industry. Outside of China, is also known for performing at the 2008 Olympics Ceremony, joined by Sarah Brightman to sing the official song You and Me. Liu actually has a small Olympic pin on his hat as a nod to the Beijing 2008 Olympics.

Liu Huan is praised for being down-to-earth, as he's singing at the Gala wearing casual clothes (a pin on his cap is a nod to the 2008 Olympics!) and he didn't even buy a new jacket for the occasion – some Weibo users found this older pic of him wearing the same pic.twitter.com/t5LyjmYoVH

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) January 31, 2022

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Our Era

Jan 31 23:40

The song Our Era (我们的时代) is performed by Zhang Ye (张也) and Lü Jihong (吕继宏) who have often sung together at earlier Spring Festivals, mostly singing patriotic songs bringing an ode to China, Chinese people, and China’s landscapes.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Special Segment

Jan 31 23:43

Like every year, this is the part of the show where some ‘exemplary persons’ get honored for their accomplishments. This special segment pays a tribute to recipients of the July 1st Medal, the Party’s highest honor, recognizing exceptional service and contributions to the Party and the country.

——–

Love Together

Jan 31 23:46

We suddenly find ourselves immersed in an underwater world together with Chinese singer-songwriter Li Ronghao and Taiwanese singer Angela Zhang for the song Love Together (爱在一起).

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Yellow River, Yangtze River

Jan 31 23:52

Mainland China, HK, Macau, and Taiwan are all represented on stage for this song!

This song (黄河 长江) is performed by Chinese top actor and singer Chen Kun (陈坤 , 1979), who is also known as Aloys Chen. Together singing with him are Taiwanese singer Jam Hsiao and Hong Kong rapper/singer/multi-talent Jackson Wang. From Macao there’s the musical artist Sean Pang (Pang Veng-Sam/彭永琛).

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

The Bells of Spring

Jan 31 23:55

The Bells of Spring (春天的钟声) is a song performed by Gala veteran Sun Nan and the singer Tan Weiwei.

Sun Nan (孙楠) is a famous Chinese Mandopop singer who performed at the Gala multiple times over the past year, including the iconic 2016 performance where he danced together with 540 robots.

Tan Weiwei (谭维维), also known as Sitar Tan, is a singer from Sichuan who rose to fame when she became a runner-up in the Super Girl talent show. In 2020, she released a noteworthy album titled 3811 which focused on the struggles women in China are facing, with each of the 11 songs on the album telling stories of women from diverse backgrounds.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Twelve O’Clock Moment

Jan 31 0:00

Countdown!

It’s twelve o’clock. Happy New Year, everybody!

This special moment is celebrated together with Chinese astronauts Zhai Zhigang, Wang Yaping, and Ye Guangfu. The three were sent into China’s space station aboard the Shenzhou-13 spaceship on October 16, 2021, for a six-month stay – the longest ever in-orbit duration for ‘taikonauts.’

——–

Winter Olympics Special

Feb 1 00:09

We just saw Ice and Snow Twinkling in the Chinese Year under the guidance of the renowned conductor Chen Xieyang, who is also Honorary Music Director of Shanghai Symphony Orchestra.

Following were some words from International Olympic Committee (IOC) President Thomas Bach. Last week, the Olympic chief met face-to-face with Xi Jinping as China is getting ready to host the Winter Games.

Then this is the official Olympic song Light Up the Dream (点亮梦) performed by baritone Liao Changyong and Hongkong pop diva Coco Lee. On stage with them are 19 foreign hosts of CGTN.

Light Up Your Dreams was released in September 2021 by the Beijing Winter Olympic Organizing Committee as a song meant to communicate positivity and hope (“There’s a miracle waiting for you after the storm”).

Also performing: China Disabled People’s Performing Art Troupe.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Online criticism

Feb 1 00:13

Some online criticism on an earlier short play performed tonight about the hospital staff couple arguing about a spot to go abroad. The husband told the wife not to go because she is female. The online doctor network 丁香园 is now pointing out it’s sexist to say females should not go abroad as people “would be all focusing on how pretty she is instead of getting medical help.”

——–

Hotpot Sonata!

Feb 1 00:20

After the Song of the Land we have now switched to Hotpot Sonata (火锅奏鸣曲).

This song is an ode to hotpot! And we love hotpot!

The performance, among others, is by Chongqing Song and Dance Troupe.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

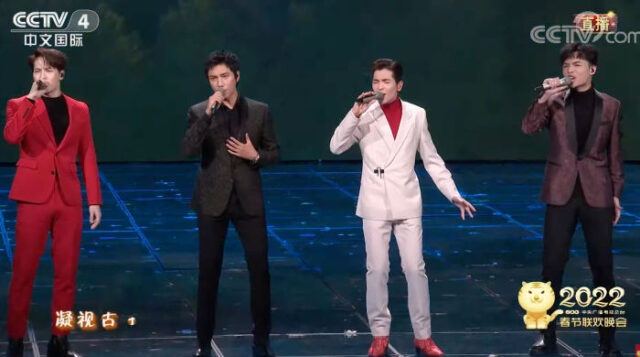

Creative music, dance, poetry and painting “Reminiscence of the South”

Feb 1 00:23

This song is called Remembering the South (忆江南) and is performed by a male group of older and younger performers, including the 68-year-old Chinese mainland actors Pu Cunxin(濮存昕, 68 years old), Feng Yuanzheng (冯远征, 59 years old), Ding Zhi-Cheng (丁志诚, 58 years old), and the Taiwanese actor Li-Chun Lee (李立群, 69 years old).

Among the younger singers (1980s/1990s), there’s Ayanga (阿云嘎), Chinese musical theater actor, singer and songwriter of Mongol ethnicity; Taiwanese Mandopop singer Aska Yang (杨宗纬), Chinese singer Shawn Zheng aka Zheng Qiyuan (郑棋元) and the Chinese operatic tenor Cai Chengyu(蔡程昱).

Many on social media find this performance so beautiful that they wonder why it was scheduled so late in the evening.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Happy Hour

Feb 1 00:26

Chinese actor Zhu Yilong (朱一龙, 1988) is on stage singing the song Happy Hour (欢乐时光). It is not the first time for the Beijing Film Academy graduate to take part in the show. Last year, he performed together with Jackie Chan in one of the most anticipated acts of the night, which was a performance dedicated to all the health workers during the epidemic.

With Zhu there is the “queen of TV ratings”, Chinese actress Zhao Liying (赵丽颖), there’s TFBoys leader Karry Wang aka Wang Junkai (王俊凯), and Yisa Yu aka Yu Kewei (郁可唯).

Dance by Jilin City Song and Dance Troupe, China Post Art Troupe, Shandong Arts Institute, Zhongnan University of Nationalities School of Music and Dance, and the Beijing Modern Music Training Institute.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

——–

Song “Unforgettable Tonight”

Feb 1 00:23

As always, the last song of tonight is Unforgettable Night (难忘今宵), the traditional closing song of the Spring Festival. The song was composed in 1984 when CCTV was preparing for its second Spring Festival Gala. Chief director Huang Yihe invited Qiao Yu and Wang Ming to write a closing song for the Gala in a simple yet popular style. The lyrics are by Qiao Yu (乔羽), the music is by Wang Ming (王酩).

Every year, the song is sung by Li Guyi (李谷一), who became famous with the song Homeland Love (乡恋) around the time of China’s Reform and Opening Up – the singer and her songs are nostalgic for many viewers. Li Guyi also appeared at the very first version of the Gala in 1983 and became the singer that sang the most at the event. She is singing together with Yang Hongji (杨洪基), Huo Yong (霍勇), and Yi Liyuan (伊丽媛).

With her on stage are all performers out tonight. It’s a wrap! Thank you for joining us and cheers to the Year of the Tiger.

Link to this performance on YouTube here.

By Manya Koetse, together with Miranda Barnes

1 For more on the political and socio-cultural meaning of the Gala, see Gao Yuan, 2012, “Construction of National Identity Through Media Ritual: A Case Study of the CCTV Spring Festival Gala,” Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Media & Communication Studies;

Yuan Yan, 2017, “Casting an ‘Outsider’ in the Ritual Center: Two Decades of Performances of ‘Rural Migrants’ in CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala,” Global Media and China 2 (2): 169-182.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

China Arts & Entertainment

When an Entertainment Scandal Gets Political: How Wong Kar-wai Survived a Nationalist Storm

The 2025 scandal surrounding Wong Kar-wai shows that public outrage only produces consequences when it aligns with official interests.

Published

3 weeks agoon

December 18, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

In 2025, Wong Kar-wai found himself at the center of one of China’s most explosive entertainment scandals of the year, one that began as a labor dispute and spiraled into a nationalist firestorm. But when this entertainment-industry controversy crossed into political red lines, something unexpected happened.

It’s safe to say that 2025 wasn’t the best year for Wong Kar-wai (王家卫, 1958), one of the most famous Chinese-language film directors in the world. The Hong Kong movie director is known for classic works like Chungking Express and In the Mood for Love. Besides his work, his iconic sunglasses are also famous – he rarely goes without them and is even nicknamed ‘Sunglasses’ (墨镜) or ‘Sunglass King’ (墨镜王) on Chinese social media.

But this year, discussions about Wong Kar-wai have gone well beyond his talent and looks. He became embroiled in what would turn into one of China’s biggest entertainment scandals of the year after a former staff member set out to expose him for exploitation and misconduct. Once the controversy spilled from entertainment into political territory, however, the dynamics of the story changed entirely.

A Fight for Credit

This story begins with the young Chinese screenwriter Gu Er (古二, real name Cheng Junnian 程骏年). He is the one who publicly accused Wong of exploitation and unethical work standards on social media (a story which we previously covered here).

Gu Er, a New York Film Academy graduate, returned to China after his studies and began building a career. In 2019, he joined the production team of Wong’s popular TV series Blossoms Shanghai, working long hours for meager pay, despite suffering from Kennedy’s disease, a motor neuron illness similar to ALS.

Cheng Junnian 程骏年, better known as Gu Er

In 2023, after the show premiered, Gu posted an article on Chinese social media titled “The Truth Behind the Writing of Blossoms” (《繁花》剧本的创作真相). He argued that he should have been credited as one of the principal writers but was instead listed only as a “preliminary editor,” buried at the end of the credits. The post sparked some discussion, but the controversy quickly faded.

It was not until last September that Gu Er released another essay titled “My Experience as a Screenwriter for Blossoms: A Summary” (我给《繁花》做编剧的经历——小结), which drew widespread attention. In the piece, he accused Wong Kar-wai of exploitation and detailed his creative work on the series, while also claiming that he was required to cook meals and run personal errands for Wong.

At one point, Gu Er describes how lead screenwriter Qin Wen (秦雯) allegedly tried to remove him from the production team after presenting his draft script as her own. According to Gu, Wong Kar-wai responded dismissively: “It’s just a few thousand yuan; he’s an assistant and can also write the script, it’s a bargain!”

Throughout 2025, Gu Er used his WeChat account to document his experiences and to upload audio recordings of conversations with members of the production team, including Wong Kar-wai and Qin Wen. These recordings were presented as evidence supporting his claims of exploitation, verbal abuse, and the denial of screenwriting credit.

In response to the controversy, the official account of the Blossoms Shanghai television series issued multiple statements denying that Gu Er deserved screenwriting credit and accusing him of abusing his position to secretly record private conversations among staff. The production team vowed to take legal action, and Gu Er’s entire WeChat account was soon shut down.

Leaked Recordings and Growing Backlash

Although his WeChat presence was erased, Gu Er refused to stay silent. In early November of 2025, he opened a new Weibo account (@古二新语) and, seemingly burning all of his bridges, continued releasing recordings involving Wong Kar-wai and members of the Blossoms Shanghai production team, triggering an unexpected shockwave over the past few weeks.

Gu Er released a series of audio recordings featuring Wong Kar-wai and others, including screenwriter Qin Wen and her assistant Xu Siyao (许思窈). In some of these recordings, they are heard mocking Gu Er; Qin appears to struggle to recall plot details she allegedly wrote herself; and Xu Siyao openly admits that an important storyline in Blossoms Shanghai originated from Gu Er’s writing.

Visuals from Blossoms Shanghai.

Wong Kar-wai and Qin Wen also spend a surprising amount of time ridiculing figures across the Chinese film and television industry, from respected senior veterans to obscure streaming-film directors, dismissively labeling them as “fake.”

What stunned the public even more were Wong Kar-wai’s crude remarks about actresses. In one recording, he comments on actress Jin Jing’s breasts and jokes, “I must get her” (“我一定要搞金靖”). Jin is not a major star, and in the final cut of Blossoms Shanghai, all of her scenes were removed. In another clip, Wong addresses screenwriter Qin Wen in a sexually suggestive and harassing tone, saying that if she had a body like Jin’s, she would not have “survived” her early years in the industry as a writer, because “I would definitely have taken you” (“我一定收你”).

Qin Wen

After this wave of leaks, the recordings—together with Gu Er’s earlier accusations—spread widely across major Chinese social media platforms. Many netizens expressed disapproval of the misogyny, gossip, and backbiting revealed in the recordings and began reevaluating Wong Kar-wai as a person, as well as his past works. Others questioned the legitimacy of Gu Er’s methods, particularly the recordings and leaks. Legal experts noted that secretly recording conversations could violate privacy laws, and that selectively edited clips might even constitute defamation.

Crossing the Red Line

Then, on November 8, Gu Er released a new recording that fundamentally altered the nature of the incident. The audio features a conversation among Wong Kar-wai, Blossoms Shanghai co-director Li Shuang (李爽), and producer Peng Qihua (彭绮华), in which they discuss COVID controls, Japan, and China’s political system.

In the recording, Wong says that the Communist Party only wants “chives” (jiǔcài, 韭菜) to harvest and describes China as a “greedy one-party state.” In Chinese internet slang, jiǔcài refers to ordinary people who are repeatedly exploited, compared to chives that are cut and grow back, only to be harvested again. When Li mentions his collection of Japanese katanas and samurai outfits, Wong jokes that, given China’s current tensions with Japan, if the collection were discovered, Li would be publicly denounced and paraded, much like during the Cultural Revolution.

Wong even suggested: “If they find [the samurai swords], just put a Chinese flag on them and say you really hate those Japanese devils.”

The Weibo post was deleted within minutes, but the recordings spread quickly.

Nationalist netizens flooded Wong’s comment section, calling him a hànjiān (汉奸, traitor to the Chinese nation), and demanding that he “get out of China.” Some conspiracy-minded users even claimed that the title of Wong’s famous TV series Blossoms (繁花 fánhuā) was intentionally chosen because it sounds like “anti-China” (反华 fǎnhuá), alleging that Wong had embedded a subversive message in the title.

Suddenly, many who had previously viewed the scandal as mere entertainment began taking sides—calling for the show to be taken down and for investigations into Wong, Li, and others involved.

Unusual Twist in a Familiar Script

In China’s public sphere, once criticism touches on the state or the Party, everything becomes more complicated. Many began questioning whether Gu Er had gone too far in leaking these conversations, and whether this was a political terror tactic disguised as personal justice.

Weaponizing nationalism to ruin a public figure is actually nothing new.

Ten years ago, CCTV host Bi Fujian (毕福剑) was recorded at a private dinner mocking Mao Zedong and was immediately fired, vanishing from public life. In 2021, actor Zhang Zhehan (张哲瀚) was canceled after taking photos near the controversial Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo—a site that honors Japan’s war dead, including convicted war criminals. In 2022, writer Yan Geling (严歌苓) was erased from the Chinese internet almost overnight after calling Xi Jinping a “human trafficker” in commentary about a trafficking case.

Given this history, and the fact that Wong has remained silent since the leaks began, mainland audiences now fear that Wong Kar-wai could join China’s celebrity “blacklist.” Some even worry they might never see In the Mood for Love again, others fear a broadcast ban for Blossoms.

Will Wong Kar-wai become the Next Bi Fujian? All past punishment-for-speech cases have followed a familiar script: a leak emerges, nationalists erupt, official mouthpieces like Xinhua step in to shape the narrative, and punishment follows swiftly. In Bi Fujian’s case, for example, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection issued a public condemnation within a week.

But this time, although nationalists are already outraged on social media and calling for Wong’s “anti-China” remarks to be punished, not a single major central media outlet has echoed their anger. In fact, shortly after Gu released the new recordings, the Blossoms team issued a statement accusing him of fabrication and malicious slander—and The Paper, a state-affiliated Shanghai outlet, amplified it. That was the first signal of how authorities might lean.

Too Valuable to Cancel?

Does this all mean China has become more tolerant of political criticism? Is the red line for what can and can’t be said shifting? Some believe the only reason Wong escaped harsher consequences is that he didn’t mention specific leaders by name, which is the quickest way to get into serious trouble. While that’s plausible, another reason may carry more weight: Wong Kar-wai is useful to the state’s cultural agenda.

Despite the comments in the recordings, Wong’s stance toward the authorities is not overtly hostile. In recent years, he has cooperated with state-backed projects. Blossoms, in particular, is part of Shanghai’s cultural branding campaign, with full support from Party-led propaganda departments. It received major state funding and was included as a central project on CCTV’s 2024 slate.

Wong is also a globally recognized auteur with real prestige in the West, making him valuable to China’s propaganda strategy of “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国故事).

Dropping such a cultural asset over a scandal stirred up by a disgruntled writer would be politically and culturally costly. This might explain why the official response has been unusually mild.

Many observers mistakenly assume that in China, once public outrage reaches a certain level, authorities will respond accordingly. But that’s only true when popular opinion and official interests are aligned. When they’re not—when the Party-state sees strategic value in protecting someone—public outcry changes nothing. If the Party believes Wong is worth keeping, then some of his comments will simply be forgiven.

The Cost of Speaking Out

At the center of this entire story is Gu Er. Was he wrong to weaponize nationalist outrage? Were his methods excessive or dangerous? Reactions are mixed. Some argue that leaking private recordings (especially political ones) is troubling and contributes to a climate of fear and self-censorship. Others sympathize, believing that Gu Er, who has suffered so much both physically and emotionally, shouldn’t be judged too harshly.

In the well-known Fanpai Yingping (反派影评) podcast, film journalist Bomi argued that Gu didn’t intentionally politicize the conflict; rather, he was responding within a system that had already politicized his case. Wong’s team never approached the issue as a civil labor dispute. They had enough opportunities to negotiate or settle, but instead, but chose not to . Perhaps it was arrogance. Or perhaps a confidence that the show, backed as a state-supported “main melody” (主旋律) production tied to enormous interests, would never be abandoned.

There seems to have been a clear mission to silence Gu Er. After shutting down his WeChat account, members of staff allegedly tried to intimidate him by visiting the house of his 90-year-old grandmother to deliver legal letters.

In the November 8 statement by the team, they accused him of “inciting social division” (“煽动社会对立”) and “manipulating negative emotions” (“诱导负面情绪”) and claimed he was “evading domestic legal investigation” (“逃避国内司法调查和认定”) by staying overseas—all language that is reminiscent of official state announcements. Some netizens even suggested it evoked the tone of old-school ideological and political denunciation—strong on rhetoric but lacking in substantive legal action. They frame this entire story into the context of a powerful production crew violating labor law treating a powerless writer like a political criminal.

The repercussions of this controversy are far from over, and to what extent it will have consequences for both Wong Kar-wai and Gu Er remains to be seen. Will Wong ever speak out? Will Gu Er be silenced forever?

Regardless, it is clear that Wong’s reputation has suffered. Long regarded as a “hero” of Chinese cinema, this incident has changed how many in mainland China now perceive the famous “Sunglasses.” Some call him a misogynist; others denounce him for exploiting staff. Still others see him as a hypocrite, suggesting that although he criticizes authoritarianism in the leaked recordings, he operates and thrives within that very system. One Weibo commenter wrote that the “Sunglasses King turned out to be the villain of the story.”

Although Gu Er has also received criticism for his actions, he has encouraged others through his insistence on standing up to those in power who bullied and discredited him. Recently, another screenwriter posted on Xiaohongshu about a similar experience: after independently completing the full script for a Chinese drama, he discovered that the boss had listed themself as Head Screenwriter in the end credits. The post was tagged “Gu Er” and received hundreds of comments, with many users sharing their own stories of being exploited as scriptwriters.

Even turning the dispute into a political issue failed to bring Gu Er any justice or revenge on his exploitative former employer. Still, he has gained something else: recognition from others, for whom his resistance has become a source of inspiration. Even if it was not the kind of recognition he originally sought, Gu Er still gets his credit in the end.

By Ruixin Zhang edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Eye on Digital China, powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Celebs

China Trend Watch: Quiet Nationalism, Loud Statements, and Nanjing Memorial Day

From war memory to viral eggs, salty cakes, an unfortunate dinner party and farewell to an iconic actress.

Published

3 weeks agoon

December 14, 2025

🔥 China Trend Watch — Week 50 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China. This edition was sent to paid subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to the Eye on Digital China newsletter. This is the China Trend Watch edition — a quick catch-up on real-time conversations.

I’ve rounded up my latest China trip that brought me from Chongqing to Nanjing, Wuhan, Zaozhuang and Beijing, for some of my research on Chinese remembrances of war. Along the way, I have met many friendly people and had interesting converations, from hanging out with a group of Wuhan teenagers to lively conversations with retired seniors in Shandong.

A small and short personal observation, if I may, regarding the current tensions between China and Japan.

I vividly remember the atmosphere on the streets during earlier moments when tensions ran sky-high—most notably in 2012, after a major diplomatic crisis erupted over Japan’s nationalization of several disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. That episode triggered large-scale anti-Japanese protests across China and spilled unmistakably into everyday life. In Beijing’s Sanlitun area, for instance, there was a street food vendor who put up a large sign proclaiming, “The Diaoyu Islands belong to China.” In the hutong neighborhoods, it seemed as though virtually every household had hung a Chinese flag by its door. Books about Japan that I purchased locally later turned out to have entire pages ripped out. My favorite sushi restaurant suddenly displayed a sign explaining that its brand was, in fact, very Chinese and had nothing to do with Japan. Nearby, in the clothing markets around the Beijing Zoo, T-shirts bearing nationalistic slogans related to the islands dispute were on sale at multiple stalls.

By contrast, during my most recent stay in Nanjing and beyond—despite the increasingly militant tone of state media and social media campaigns surrounding Japan, and despite the undeniable persistence of anti-Japanese sentiment—I noticed far fewer visible expressions of it in daily life. There were no slogan T-shirts, no banners, no overt street-level signaling. While news came out that a string of Japanese performances in China were canceled, I noticed hotel waitress fully dressed in a Japanese kimono at an in-house Japanese restaurant. Local bookstores are filled with works by Japanese authors, and Japanese popular culture appear to be thriving and coexisting comfortably with China’s own flourishing ACG (anime, comics, and games) industry.

Is there simply less anti-Japanese sentiment than over a decade ago? Or is it, perhaps, that in today’s highly digitalized Xi Jinping era, nationalist narratives are more tightly managed and increasingly channeled online—making people more cautious, more restrained, or simply less inclined to express political sentiments openly in public space?

A cab driver in Chongqing told me he believed there was “something wrong” with Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi and the influence she has had on bilateral relations since her rise to power. While supporting his government’s tough stance and expressing sadness over the scars left by war, he also mentioned that he had enjoyed a pleasant conversation earlier that same morning with a young Japanese man he had driven to the train station.

“We didn’t talk about the latest clash,” he said. “If find that too sensitive to mention. He spoke Chinese, he studied Chinese, like you. I don’t hate today’s Japanese people at all. In the end, we’re all just people. What’s happening now is something between the leadership.”

He spoke at length while driving me to the station, signaling that the topic clearly weighed on him. It left me with the sense that the absence of banners or T-shirts does not mean the issue has faded from everyday life, only that it is not expressed as a mass spectacle like it was in earlier years. It has become quieter, more online, and more filtered through official narratives, but it is still very much alive.

There is a lot more to say, but it is Sunday after all, and there is plenty more to read here, so let’s dive in.

- 🍓 Chinese consumers were pretty salty this week when discovering their pricey strawberry cake from Alibaba supermarket chain Hema (盒马) tasted all wrong. Hema acknowledged a production issue (they didn’t say it outright, but salt was allegedly used instead of sugar) and the incident triggered discussions about food safety & quality control in automated food production, especially when such a major mistake happens at high-profile companies.

- 🌡️ China’s announced ban on mercury thermometers (as of Jan 1st 2026) has sparked a buying frenzy, as many consumers, reluctant to switch to electronic alternatives, still prefer mercury models for their perceived accuracy and convenience. Despite nearly half of annual mercury poisoning cases being linked to broken thermometers, prices have now surged from around 4 yuan ($0.6) to over 30 yuan ($4.25), and stores have reported complete sellouts.

- ❄️ Beijing welcomed its first snowfall of winter 2025 this week, leading to lovely social media pics and the Beijing Palace Museum tickets selling out instantly. Experiencing and capturing that first snowfall at the Forbidden City has become somewhat of a holy grail on social media.

- 🕵️♂️ A local construction site in Shanghai unexpectedly became the scene of a modern-day treasure hunt after dozens of residents armed with shovels and metal detectors rushed to the area following online rumors that silver coins (including valuable older ones) had been found. Authorities had to intervene and, while not confirming the rumors, emphasized that any buried cultural relics belong to the state.

- 🇷🇺 Since this month, Chinese citizens can enter Russia visa-free for up to 30 days, a policy that led Chinese state media to claim that “Russia is replacing Japan as a new favorite among Chinese tourists.” On social media, however, the vibe is different, with travelers complaining about high prices, poor internet, lack of online payments, unreliable ATMs, and the need for thorough trip preparation — all reasons why Russia is unlikely to become the go-to destination for the Chinese New Year.

- 🫏 An investigation by Beijing Evening News revealed that many of the capital’s popular donkey meat sandwich shops are actually serving horse meat without informing customers. China’s donkey shortage — driven by declining domestic supply, rising demand for the traditional Chinese medicine Ejiao (which uses donkey hides), and an African export ban — has been a hot topic this year. Now that it’s directly affecting a beloved delicacy, the issue is drawing even more public attention.

1. Why This Year’s Nanjing Memorial Day Felt Different

Posters published by various Chinese state media outlets to commemorate the Nanjing Massacre.

December 13 marked the 88th anniversary of the fall of Nanjing, and this year’s Nanjing Memorial Day (南京大屠杀难者国家公祭日), although described as a low-key commemoration by foreign media, was trending all over Chinese social media.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, on December 12, 1937, the Japanese army attacked Nanjing from various directions, and defending Chinese forces suffered heavy casualties. A day later, the city was captured. It marked the beginning of a six-week-long massacre filled with looting, arson, and rape, during which, according to China’s official data, at least 300,000 residents, including children, elderly, and women, were brutally murdered.

This year, the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Day, which was first officially held as a state-level event in 2014, carried extra weight. This dark chapter of history has continuously been a sensitive topic in Sino-Japanese relations, but with recent diplomatic tensions between the two countries reaching new heights, the Memorial Day was especially tied to current-day relations between China and Japan and to Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who has been described by Chinese media as an “ultranationalist” with tendencies to downplay Japan’s wartime aggression. Takaichi’s November 2025 parliamentary statement that a Chinese military action against Taiwan could be considered a “survival-threatening situation” for Japan, allowing for the deployment of its Self-Defense Forces, continues to fuel Chinese anger.

The link between history and current-day bilateral relations was visible not only on social media, but also during the commemoration itself, where Shi Taifeng (石泰峰), head of the ruling Communist Party’s Organization Department, said that any attempt to revive militarism and challenge the postwar international order is “doomed to fail.”

Besides the many online posters disseminated by Chinese official accounts on social media focusing on mourning, quiet commemoration, and honoring the lives of the 300,000 Chinese compatriots killed in Nanjing, one official online visual stood out for displaying a louder and more aggressive message—namely that posted by the official Weibo account of the Eastern Theater Command of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (@东部战区).

The visual posted by the PLA Eastern Theater Command, titled: Rite of the Great Saber (大刀祭).

The visual showed a strong hand holding a giant blood-stained blade that is beheading a skeleton wearing a helmet marked “militarism,” with images related to the Nanjing Massacre visible on the blade and, behind it, a map of East Asia. The number “300000” appears in red, dripping like blood. At the top, the characters read “Rite of the Great Saber” or “The Great Saber Sacrifice” (大刀祭).

The official account explained the visual, writing: “(…) 88 years have passed and the blood of the heroic dead has not yet dried, [yet] the ghost of militarism is making a comeback. Each year, on National Memorial Day, a deafening alarm is sounded, reminding us that we must—at all times hold high the great saber offered in blood sacrifice, resolutely cut off filthy heads, never allow militarism to return, and never allow historical tragedy to be repeated.”

The text’s “cut off filthy heads” phrasing is similar to part of a now-deleted tweet sent out last month by the Chinese Consul General in Osaka, Xue Jian (薛剑), who responded to Takaichi’s controversial Taiwan remarks by writing (in Japanese): “If you come charging in on your own like that, there’s nothing to do but cut that filthy neck down without a moment’s hesitation. Are you prepared?” (“勝手に突っ込んできたその汚い首は一瞬の躊躇もなく斬ってやるしかない。覚悟が出来ているのか。”)

The recent visuals, social media approach, and shifts in texts reflect a clear change in tone in Chinese official discourse regarding Japan and the memory of war, moving the narrative from victimhood toward a more confrontational and militant tone.

2. He Qing, China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty”, Passes Away at 61

He Qing. Images on the sides: the four famous roles in China’s most iconic tv dramas.

China’s “No. 1 Classical Beauty” (古典第一美女), He Qing (何晴), who starred in all four of China’s most beloved and canonical television dramas, passed away on Saturday at the age of 61. On December 14, news of the famous actress’s passing was trending across virtually all Chinese social media apps.

Born in 1964 into an artistic family in Jiangshan, Zhejiang Province, He Qing received traditional Chinese opera (Kunqu) training at the Zhejiang Kunqu Opera Troupe. Her debut in the entertainment industry may have come by chance, as she reportedly once met Chinese director Yang Jie (杨洁) on a train, which led to her joining the production of Journey to the West (西游记), where she played Lingji Bodhisattva (灵吉菩萨).

In China, He Qing is remembered as a veteran actress in much the same way that some famous Hong Kong actresses became renowned for their beauty, iconic roles, and for essentially becoming household names. More than just glitter and glamour, He Qing was especially a symbol of classical Chinese beauty and literary culture. She was the only actress to star in screen adaptations of all four of China’s “Four Great Classical Novels” (演遍四大名著): besides Journey to the West (西游记, 1986), she also appeared in Dream of the Red Chamber (红楼梦, 1987), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义, 1994), and Water Margin (水浒传, 1998).

She was married to fellow actor Xu Yajun (许亚军), with whom she had a son, Xu He (许何). Although the two later divorced, she remained close to her ex-husband and even befriended his new (and fourth) wife, Zhang Shu (张澍).

In 2015, He Qing was diagnosed with a brain tumor. After her diagnosis, she withdrew from the entertainment industry to focus on her recovery and lived a low-key life in her later years.

Her passing has prompted an outpouring of tributes from Chinese netizens and colleagues in the entertainment industry. Mourning her loss comes with a sense of nostalgia for the past, and many have praised He Qing for her timeless beauty and authenticity, which will be remembered long after her passing.

3. And Then There Were None: Dinner Party of Ten Leaves One Man with the Bill

Ten dine together, nine slip away..one left for the bill, who he refused to pay…

Do you know that nursery rhyme where ten little soldiers disappear one by one until none remain at the end? That is more or less what happened earlier this month in Chongqing, when ten people dined together at a restaurant, but—once it came time to pay—nine people left one by one.

One had to answer a phone call, another had to use the restroom, and in the end, just before midnight, only Mr. Zhang was left, facing a bill of 1,262 yuan ($180), which he refused to pay. He argued that he could not afford it and that the dinner party hadn’t been initiated by him at all; as merely a participant, the bill shouldn’t have been his responsibility.

After the restaurant called the police, the organizer of the dinner was contacted. But he, too, said he couldn’t pay. Through police mediation, Mr. Zhang then wrote a written commitment promising to pay the bill the following day and left his ID as collateral, but he still failed to make the payment.

By now, the restaurant is planning to sue and has also contacted the Chinese media. According to Zhang, who apparently has been unable to contact his “friends” to collect the money: “I did make the promise, but if I pay the money, wouldn’t that make me a sucker?” (“我的确承诺了,但你说我把钱付了,我是不是冤大头啊”)

As the story went completely viral (by now, even Hu Xijin has weighed in) comment sections filled with broader social reflections on alcohol-fueled group gatherings and unclear payment rules, where one person sometimes ends up paying for everything despite feeling it wasn’t their role to do so. In this era of digital payments, many argue it should be easy enough to go Dutch and settle the bill immediately via a group payment app.

Although Zhang is seen by some as a victim, others argue that he is still a “sucker” for not paying after having promised to do so. As one commenter put it: “Out of the ten of them, not a single one is a good person.”

Real Person Vibes [活人感 (huóréngǎn)

Every December, the ten most popular buzzwords, key terms, or expressions of the year are listed by the Chinese linguistics magazine Yǎowén Jiáozì (咬文嚼字), selecting words that reflect present-day society and changing times. Each year, the list goes trending and is widely disseminated by Chinese media.

This week, the 2025 list was released, including terms such as Digital Nomads 数字游民 (shù zì yóu mín), Sū Chāo (苏超), referring to the hugely popular amateur Jiangsu Super League football competition, and “Pre-made ××” (预制, yù zhì), following a year filled with discussions about pre-fab and pre-made food (see article).

My favorite word on the list is “Real-Person Vibes” (活人感 huó rén gǎn). The term literally consists of three characters meaning “living – human – feeling,” and it describes people, stories, or things that feel unpolished, spontaneous, and unfiltered—something that has become increasingly relevant in a year dominated by AI-generated content and visuals.

Amid over-curated feeds and AI-produced text, we crave huóréngǎn: authenticity, small imperfections, and liveliness as an antidote to a digital, artificial world.

The 9:12 Boiled Egg That Took Over Douyin

How do you get a perfect boiled egg? A Douyin user known as “Loves Eating Eggs” (爱吃蛋) has become all the rage after leaving a precise comment on how to boil eggs. His advice: First boil the water, then add the eggs, boil for exactly 9 minutes and 12 seconds, remove, and immediately run under cold water.

That simple tip catapulted his follower count from around 200 to over 3.5 million in a single week (I just checked—he’s up to 4.2 million now).

The new viral hit is a 24-year-old self-proclaimed egg expert (of course, his English nickname should be the Eggxpert). He claims to have eaten 40 eggs a day for the past five years and knows exactly how every second of boiling, frying, or stirring affects an egg. He regularly posts videos showing eggs cooked for different lengths of time.

It has earned him the nicknames “Egg God” (蛋神) and “Boiled Egg Immortal” (煮蛋仙人), and has sent boiled eggs (9 minutes and 12 seconds exactly) all over social media feeds.

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China China Trend Watch. For slower-moving trends and deeper structural analysis, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

And if you happen to be reading this without a subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

Housekeeping reminder: if you’re receiving duplicate newsletters, it’s likely because you signed up on both the main What’s on Weibo website and the Eye on Digital China Substack. If you’re a paying member on one of the two, you may receive the premium newsletter twice. Please keep the one you’re paying for, and feel free to unsubscribe from the other.

Many thanks to Miranda Barnes for helping curate some of the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or

email me. First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

Why Were 100,000 Pregnant Women’s Blood Samples Smuggled Out of China?

When an Entertainment Scandal Gets Political: How Wong Kar-wai Survived a Nationalist Storm

China Trend Watch: Quiet Nationalism, Loud Statements, and Nanjing Memorial Day

From Nobel Farewell to ‘VIP Toilets’: What’s Trending in China

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

From Tents to ‘Tangping Travel”: New Travel Trends among Young Chinese

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment6 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment6 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Digital12 months ago

China Digital12 months ago“Dear Li Hua”: The TikTok/Xiaohongshu Honeymoon Explained

-

China Insight5 months ago

China Insight5 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest