Newsletter

Weibo Watch: An Explosive Situation

It’s been an explosive week on Chinese social media. Since Tuesday, when Japan formally announced its decision to start releasing waste water from Fukushima, related topics have been dominating Chinese social media platforms.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #12

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – A toxic mix of factors

◼︎ 2. What’s Trending – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What More to Know – Highlighting 8 hot topics

◼︎ 4. What Lies Behind – Report on anti-Black racism in China

◼︎ 5. What’s Noteworthy – Yellen’s magic mushrooms

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – China’s “Lord of the Rings”

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Anti-Japanese riots

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – “Harvesting chives”

Featured header contains work by Weibo creator “A Boy Who Loves to Learn” @一个热爱学习的男孩, and by Toutiao writer “It’s Not That Complicated” @局势很简单

Dear Reader,

It’s been an explosive week on Chinese social media. Since Tuesday, when Japan formally announced its decision to start releasing waste water from Fukushima into the Pacific, related topics have been dominating Chinese social media platforms.

It’s not that often that you see such huge topics on Chinese social media, swelling like a tidal wave, sweeping through threads, comments, and spanning various sectors of society — engaging state media, businesses, influencers, celebrities, and the public.

Grocery stores experienced an influx of people stockpiling salt, with some even reselling it. Individuals queued for hours to purchase a bag of salt, and some headed to salt manufacturers for bulk purchases.

This salt frenzy stems from collective concerns about the impact of Fukushima water on food safety. Despite an existing ban on Japanese seafood, there’s unease that salt – in the near future and in the decades to come – might also become compromised due to radiation fears. There’s also a believe that salt might help in case of radiation pollution (iodized salt, however, is actually no antidote for radiation).

Some China-based Japanese restaurants made headlines for removing their Japanese decorations, advertising with their “international” cuisine – Our salmon’s from Norway! The sea urchin’s from Russia! -, or just openly telling customers they’re really not Japanese. One popular Weibo post joked that “the Japanese restaurant downstairs has finally admitted they’re not really Japanese.”

The ripple effect included consumers boycotting Japanese beauty products. On e-commerce platforms, tearful fish sellers faced worries about their business future due to contamination fears.

In the English-language social media sphere, critics dismissed the panic as unwarranted, stressing that the disposal is well within safety limits, and the environmental impact on seafood is negligible. “All of this consternation, just because of some low levels of tritium?” some asked.

Well yes.

But when you mix that with collective memories of war and humiliation, profound anti-Japanese sentiments in a deeply cyber-nationalistic environment, a media landscape where state reports on the hazards of Fukushima water amplify existing eco-anxieties, skepticism toward the G7, and a society where official narratives aren’t always trusted and individuals take their own safety precautions..

..you witness a rather explosive scenario, culminating in public unease, panic buying, and social media overflowing with hostile comments targeting Japan.

This weekend, there are many state-led hashtags trying to calm the storm, reassuring the public about salt abundance, managing over-anxiety, and ensuring the safety of domestic fish consumption. Ultimately, the anti-Japanese demonstrations of 2012 have shown the potential impact of online sentiments on real-life situations. As a precaution, the Japanese Embassy in Beijing has cautioned Japanese citizens against speaking Japanese too loudly in public and remaining vigilant. In the end, no party desires online unrest to escalate into physical violence – neither Chinese authorities, Japanese residents in China, business owners, nor everyday individuals who might be affected by such outbursts because of the clothes they wear, the car they drive, or the shop they work at.

This is our 12th ‘Weibo Watch’ newsletter, and I hope you’re enjoying the format and finding it helpful for catching up on key trends in China’s online media scene, alongside our regular website content. We’ve been tweaking the delivery schedule—weekly or every other week—and given the considerable research and effort that go into our articles (especially since I’m still primarily managing What’s on Weibo on my own), I’ve determined that it would work best to send you a more comprehensive newsletter every two weeks, coupled with a quick update on our latest articles every week.

We’ve launched our soft paywall ten months ago and while we’ve made strides (thanks to you!), we still need more subscribers to sustain our operations. If you appreciate what we do, please recommend What’s on Weibo to friends/colleagues. Your input and personal messages have been incredibly valuable, adding to our discussions on Chinese (social) media developments and improvement of the platform – so I’m super grateful for your engagement.

Miranda Barnes, who has a keen eye for the latest trends, and Zilan Qian, who’s been writing about insightful topics all summer, have contributed to this week’s newsletter.

Best,

Manya (@manyapan)

What’s Trending

1: Top Trends Surrounding Fukushima Water | There have been furious responses from Chinese media and netizens after Japan started releasing Fukushima water into the ocean: “The entire world will remember what the Japanese government did this day.” Over the past few days, at least five out of the top ten trending topics on Baidu’s hot news lists and the Weibo platform are linked to the discharge from the nuclear plant and its potential direct and indirect consequences. We explain the top 5 biggest hashtags on Chinese social media, and what’s behind them.

2:The Voice of Coco Lee | Another explosive topic this week is the scandal surrounding The Voice of China, also called Sing! China. A leaked audio recording of the late superstar Coco Lee discussing her negative experiences with the Chinese talent show became the no 1 searched topic on Weibo earlier this week. The accusations against the popular show have shaken up China’s entertainment circles and the online condemnation of ethical standards in the industry also has offline consequences.

3: Empty Hall, Full Buzz | A local Sichuan Bureau of Civil Affairs, where couples register and obtain their marriage certificate, launched a livestream to celebrate the marriage registration ceremony for new couples on August 22, marking the occasion of the Qixi Festival, often referred to as the Chinese equivalent of Valentine’s Day. The celebratory livestream gained immense traction on Chinese social media, albeit for all the unintended reasons. Instead of a much-anticipated marriage boom (结婚潮), online viewers saw an awkward empty ceremony stage.

4: Two Blazes, Same Day | It was a noteworthy Tuesday in Tianjin this week. After a major fire broke out in the Xintiandi high-rise office building, Tianjin residents soon found out that another blaze was occurring not far away, causing the plumes of smoke from both incidents to be visible from multiple locations. These successive fires stirred a certain level of unease, further fueled by online rumors falsely suggesting a third fire was in progress. Although there are not many news reports on what exactly happened, the local fire brigade reported no casualties.

What More to Know

“There’s something wrong with this water” meme.

◼︎ 1. China Responds to Japan’s Fukushima Water Disposal. The biggest topic of the week is, without a doubt, the Chinese response to Japan’s Fukushima water disposal and the anti-Japanese sentiments that have surfaced in online discussions along with a general public unrest. The first related trending topics already started on Tuesday when Prime Minister Fumio Kishida stated that, despite existing regional worries and opposition, they would begin releasing water from the ruined Fukushima nuclear plant on August 24. Although the move meets the safety standards of the International Atomic Energy Agency, China strongly opposes it. Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Wang Wenbin responded that ‘relevant departments’ in China would take necessary measures to ensure food safety. China already has tight import controls on Japanese food and has now taken extra measures to ban Japanese aquatic products. (Hashtag: “China Responds to Japan’s Formal Decision to Start Discharging [Water] Into the Sea #中方回应日本正式决定启动排海#, 320 million views).

◼︎ 2. BRICS Summit. The 2023 BRICS Summit (Aug 22-24) has remained a significant focus throughout the week in Chinese news and on Weibo, where related hashtags surged to the top of trending lists. While in Chinese media, mostly positive news was coming from South-Africa in light of Xi Jinping’s state visit and the Summit, international media were more concerned with the fact that Xi did not read his own speech for the Business Forum in Johannesburg. Instead, China’s commerce minister Wang Wentao spoke in his place. On Weibo, news of Xi’s speech was presented in a way that didn’t explicitly indicate he hadn’t given it himself. Another noteworthy moment showed how Xi Jinping’s security guards were blocked from entering the venue. However, this moment wasn’t showcased on Chinese social media. The annual summit was marked by discussions of expansion: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have been invited to become full members starting from January 1st next year. (Various related trending hashtags on Weibo, such as ‘BRICS Times’ #金砖时刻# or ‘Xi Jinping’s South Africa Journey’ #习主席非洲之行#, 410 million views).

◼︎ 3. Prigozhin’s Private Plane Crashes. Weibo saw a flurry of discussions regarding the reported demise of Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin in the early hours of August 24 after reports indicated that he was listed as a passenger on a plane that had crashed in the Tver Region of Russia. Chinese state media outlets soon shared the footage showing the plane plummeting from the sky. Drawing parallels to history, some likened Prigozhin’s situation to that of Lin Biao, a powerful politician who met his untimely demise in a 1971 airplane crash that many believe was deliberately orchestrated. (“Russian Media Report Prigozhin’s Private Plane Crashed” #俄媒称普里戈任的私人飞机坠毁#, 310 million views).

◼︎ 4. Trump in Custody.“History seems to unfold right before our eyes these days,” remarked a popular Weibo comment this week, reflecting the surge of major events. Amidst the Fukushima water disposal, BRICS, and Prigozhin’s passing, the attention also turned to the news of former U.S. President Donald Trump and his now-iconic mug shot. This image was captured as he surrendered to an Atlanta jail, facing charges of seeking to overturn Georgia’s 2020 election results. On Chinese social media, Trump has always been a source of banter (link, link, link), and that was no different now. Some people imagined that with all this political intrigue, he’s become like a star in a South Korean soap opera (Weibo hashtag “Trump in Custody” #特朗普被收押#, 150 million views).

◼︎ 5. The Voice of China Stops Broadcasting. Following the online leakage of an audio recording in which the late Chinese celebrity Coco Lee expressed her dissatisfaction with the treatment she received from the production team of The Voice of China (also known as Sing! China), the reality TV show has emerged as a significant online topic. While the program initially dismissed the controversy surrounding the leaked recording, suggesting potential manipulation and ill intentions, the situation has now escalated to the point where the show’s broadcast has been suspended as of August 25th. Zhejiang TV, the broadcasting platform, issued a statement on Weibo, announcing an ongoing investigation. Consequently, the airing of the show has been temporarily put on hold. (Hashtag “The Voice of China Suspends Broadcasts” #中国好声音暂停播出#, 730 million views).

◼︎ 6. China’s 239 Million Singles during Qixi Festival. Talk of love was in the air this week, as China celebrated the Qixi festival, often referred to as the Chinese Valentine’s Day. While couples celebrated their love for each other, attention also turned to the growing number of single individuals in the country. The figure now stands at a staggering 239 million. This revelation surfaced from the China Population Census Yearbook (2020), which additionally revealed that the average age for first marriages has shifted to 28.67, marking a 3.78-year increase compared to 2010. “There are more people who don’t want to find a partner, and for those who want to, finding a partner has become more difficult,” one top commenter wrote. (Hashtag “China Has 239 Million Singles” #我国单身人口2.39亿#, 210 million views).

◼︎ 7. Banned for Life from Visiting Pandas. Perhaps it’s time to do another update to our ‘Meanwhile in Panda News‘ series, as there’s been quite some trending panda news again. There was the news that baby panda Fan Xing, who was born in a Dutch zoo, will soon be returned to China. Another trending news item concerns two visitors who fed bamboo shoots and peanuts to pandas in Chengdu. While other zoos in China hold less strict rules, the Chengdu Research Base is not to be messed with – the safety and well-being of the pandas is their top priority. Feeding the pandas resulted in a permanent ban for these two visitors from revisiting the Chengdu zoo. (“Two Tourists Get Lifetime Ban on Visiting Panda’s in Chengdu” #2游客被终生禁入成都大熊猫基地#, 19 million views).

◼︎ 8. Switzerland Hands Seized Cultural Relics Over to China. A handover ceremony in which Switzerland returned lost cultural relics to China, including a Ming Dynasty vase, and pottery from the Han and Tang Dynasties, became a number one trending topic on Douyin on August 25. During the handover ceremony, Ambassador Wang Shiting praised the collaboration between China and Switzerland in the field of cultural relics. Both countries underlined their commitment to combat illegal import and export of cultural relics. (Douyin hashtag “Switzerland Hands Over 5 Lost Cultural Relics to China 瑞士向中国移交5件流失文物).

What’s Behind the Headlines

Screenshot shared on Weibo of VOA’s article on the HRW report.

Human Rights Watch: Addressing Anti-Black Racism on Chinese Social Media

A recent report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) argues that China needs to take more robust measures to combat anti-Black racism on social media platforms. The report suggest that both major social media platforms and Chinese authorities systematically fail to properly address this issue.

The assertion made by HRW that Chinese social media serves as a breeding ground for anti-Black racism is not new. This issue has previously attracted international criticism. Last year, BBC released a documentary titled “Racism for Sale,” exposing an online market for racist videos featuring African children made to dance and sing degrading phrases in Chinese such as “I am dumb” or “I am monstrous.” Afterward, Chinese e-commerce sites closed shops engaged in trading such videos, Weibo shut down numerous accounts sharing racist content, and government officials spoke out against such practices.

But HRW argues that there are many other manifestations of anti-Black racism in China.While the report does not delve deeply into the specifics of the content they consider racist, it does reference videos that perpetuate racial stereotypes, content that belittles interracial relationships, accounts that impersonate Black people, and state media shows featuring performers with skin darkened by makeup. Platforms like Bilibili, Kuaishou, Weibo, and Xiaohongshu should intensify efforts to remove this kind of problematic content, it argues.

While the HRW report raises significant concerns, its approach also falls short in effectively conveying this message to the Chinese people. It lumps together various issues and shows a lack of understanding of China’s online media environment and Chinese perspectives, and how China’s differing pace in addressing racial equality and anti-Black racism also stems from drastically divergent historical and social contexts (read). Telling the country in the world with the least internet freedom that they should censor more is not only somewhat Orwellian, it also strengthens existing frustrations in China that the West often acts as a morally superior enforcer on the global stage. Within this context of distrust, many suspect that when Western powers accuse China of being racist, particularly against black Africans, they actually mean to disrupt China-Africa relations because they fear China’s growing global influence.

Predictably, the common response among Chinese netizens to the report was that ‘the West’ was once again revealing its true intentions by pointing fingers at China, despite ongoing instances of racist violence occurring within their own nations. Consequently, the report ultimately misses the mark by not effectively raising awareness about anti-Black racism in China. Instead, it fosters a sense of distrust regarding the genuine motivations behind a report published with good intentions.

What’s Noteworthy

U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Yellen Had ‘Magic Mushrooms’ in Beijing |

It’s been weeks since the US treasury secretary visited Beijing, but her July visit has become a topic of discussion again after Yellen conducted an interview with CNN in which her noteworthy first meal in the Chinese capital was discussed. The restaurant where she had dinner is the Yunnan-themed ‘In and Out’ (一坐一忘), a local favorite in Beijing’s Sanlitun near the embassy area. Among other things, Yellen was served spicy potatoes with mint and stir-fried mushrooms, leading to online jokes about how the food would affect her.

The mushroom dish that is discussed here – and which has since become more popular – is called jiànshǒuqīng (见手青), which literally means “see hand blue” (in reference to turning blue when handled). It is the lanmaoa asiatica mushroom species that grows in China’s Yunnan region and is considered hallucinogenic, causing visions that locals call “xiǎorénrén” (小人人), literally: “little people,” referring to visual hallucinations where people see tiny humans. The fact that Yellen chose to eat such risky food on her first night in Beijing, ahead of important US-China talks, caused a great deal of hilarity on Chinese social media.

To prevent the mushrooms from causing poisoning and “seeing little people,” they must be handled with care and cooked thoroughly. Yellen claimed she did not have any ill effects from eating them, calling them “delicious.” Read more here.

What’s Popular

China’s ‘Lords of the Rings’ Needed Extra Support | Despite its initially underwhelming performance, the Chinese film Creation of the Gods I (封神第一部) has become a major summer box office hit in China, and the topic has become trending multiple times over the past week. With a planned budget of 3 billion yuan (approximately US$410 million), the mythological epic stands as the most ambitious and costly production in Chinese film history, having been in the works for years. Because director Wu’ershan first got the idea for this film when watching The Lord of the Rings in 2001, this first movie within the trilogy of the fantasy epic Creation of the Gods, also known as Fengshen Trilogy (封神三部曲) is also referred to as the “Chinese Lord of the Rings.”

However, despite the grand scale and hefty budget, the film struggled to capture much attention upon its theatrical release, and it took over two weeks for significant box office numbers to materialize. Social media played a pivotal role in its eventual box office success as viewers lauded the blend of traditional Chinese mythology with cutting-edge cinematic techniques. A devoted online community of fans contributed to the surge in ticket sales. This phenomenon is also called zìláishuǐ (自来水). This literally means ‘tap water,’ but it is a label for those netizens who spontaneously promote a film or artist without getting paid for it. Read more here.

What’s Memorable

2012 Anti-Japanese Riots This week, the Japanese embassy in Beijing warned Japanese nationals not to loudly talk in Japanese in public and to be careful when going out. Although many ridiculed the warning on Chinese social media, the current anti-Japanese tensions in China might remind some of September 2012, when tensions eventually led to violent anti-Japanese protests (反日游行) in different cities across China, including in Beijing, over the status of the Senkaku/Diaoyu island group. The long-standing dispute reached a zenith after the Japanese government nationalized control of three of the largest islands, triggering people to take to the streets across the country to vent their anger.

The protests led to excessives; people ravaged Japanese businesses, smashed Japanese-branded cars, threw rocks at the Japanese embassy, and burned Japanese flags. There was also a mass boycott of Japanese goods. One man from Xi’an was hit in the head by demonstrators for owning a Japanese car. In 2016, four years later, he was still hospitalized for head injury. At the time, What’s on Weibo published an article about it which you can read in our archive here.

Weibo Word of the Week

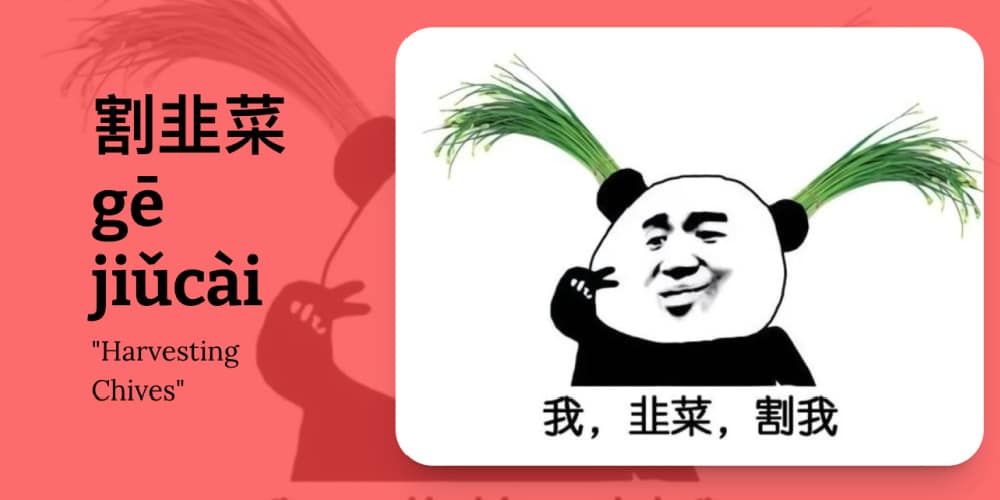

“Harvesting Chives” | Our Weibo Word of the Week is “割韭菜” (gē jiǔcài), which translates to “reaping chives.” This term refers to a situation in which inexperienced or uninformed individuals, symbolized by chives, are taken advantage of by more knowledgeable or manipulative people, often leading to financial losses for the less informed parties.

The term is widely used in the context of finance and investment, where a handful of market manipulators deceive numerous regular investors, who are often referred to as chives (“韭菜”), into buying overpriced assets. The manipulators then profit from these investments as prices suddenly plummet. The enduring vitality of chives as a plant serves as a metaphor for the unceasing influx of new investors who become ensnared in the manipulators’ schemes after the previous ones have already suffered losses and left the market.

“Harvesting Chives” or “Reaping Chives” has been frequently used amidst China’s recent property crisis, exemplified by major events like the payment suspension by Zhongzhi Enterprise Group and the potential bond default by Country Garden. Those affected by the crisis humorously label themselves as “chives” that have been harvested by a select group of senior figures within these enterprises, who are believed to have already transferred their ‘fruitful harvest’ elsewhere.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Stories that are authored by the What's on Weibo Team are the stories that multiple authors contributed to. Please check the names at the end of the articles to see who the authors are.

You may like

Dear Reader

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

A look back at the three major phases of China’s social media — and why What’s on Weibo is evolving into Eye on Digital China.

Published

3 months agoon

November 12, 2025

This edition of the Eye on Digital China newsletter by Manya Koetse was sent to premium subscribers. Subscribe now to receive future issues in your inbox.

“Do you still remember going to the internet cafe, paying 2 yuan ($0.30) per hour during the day or 7 yuan ($1) for an all-nighter? Staying up playing games and surfing around?”

It’s the kind of content you’ll often see today on platforms like Douyin or Bilibili — nostalgic videos showing smoky internet cafes (wangba 网吧) from the early 2000s, where people chatted on QQ or played World of Warcraft on old Windows PCs while eating instant noodles. These clips trigger waves of nostalgia, even among internet users too young to remember that era themselves.

Internetcafe in 2005, image via 021zhaopin.com

The current nostalgia wave you see on Chinese social media is indicative of how China’s digital world has evolved over the past 25 years, shifting from one era to the next.

As I welcome a new name for this newsletter and say goodbye to ‘Weibo Watch’— and, in the longer run, to the ‘What’s on Weibo’ title, I’m feeling a bit nostalgic myself. It seems like a good moment to look back at the three major stages of Chinese social media, and at the reason I started What’s on Weibo in the first place.

1. The Blogging Boom (2002–2009): The Early Rise of Chinese Social Media

When I first came to China and became particularly interested in its online environment, it was the final phase of the early era of Chinese social media — a period that followed soon after the country had laid the foundations for its internet revolution. By 1999, the first generation of Chinese internet giants — Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and Sina — had already been founded.

China’s blogging era began with the 2002 launch of the platform BlogChina.com (博客中国), followed by a wave of new platforms and online communities, among them Baidu Tieba and Renren. By around 2005, there were roughly 111 million internet users and 16 million bloggers, and the social impact was undeniable. 2005 was even dubbed China’s “year of blogging.” 1

Chinese writer Han Han (韩寒, born 1982), a high-school-dropout-turned–rally car racer, became one of the most-read figures on the Chinese internet with his sharp and witty blogs. He was just one among many who rose to fame during the blog era, becoming the voice of China’s post-1980s youth.

The rebel of China’s blog era, Han Han, became of voice of his generation.

When I moved to Beijing in 2008, I had a friend who was always out of money and practically lived in an internet cafe in the city’s Wudaokou district, not far from where I studied. We would visit him there as if it were his living room — the wangba was a local hangout for many of us.

Not only online forums and blogging sites were flourishing at the time, but there was also instant messaging through QQ (腾讯QQ), online news reading, and gaming. Platforms like the YouTube equivalents Tudou (土豆) and Youku (优酷) were launched, and soon Chinese companies began developing more successful products inspired by American digital platforms, such as Fanfou (饭否), Zuosa (做啥), Jiwai (叽歪), and Taotao (滔滔), creating an online space that was increasingly, and uniquely, Chinese.

That trajectory only accelerated after 2009, when popular Western internet services, including Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, became inaccessible from within mainland China.

⚡ The launch of Sina Weibo in 2009 came at a crossroads for China’s social media landscape: it was not only a time when many foreign platforms exited China, but also when internet cafes faced major crackdowns.

As a foreigner, I don’t think I ever visited internet bars in Beijing anymore by that point — internet use had largely shifted to home connections. Laptop ownership was rising, and we all had (pre-smartphone) mobile phones, which we used to text each other constantly, since texting was cheaper than calling.

Some of the mobile phones in China’s 2009 top 10 lists.

Weibo came at just the right time. It filled the vacuum left by the online crackdowns across China’s internet while still benefiting from the popularity of blogging. Weibo (微博), after all, literally means “micro-blog” — micro because the number of characters was limited, just like Twitter, making short-form posts the main way of communication.

Weibo quickly became hugely successful, for many more reasons than just timing. Its impact on society was so palpable that its trending discussions often seeped into everyday conversations I had with friends in China.

In English-language media, I kept reading about what was being censored on the Chinese internet, but that wasn’t necessarily what I wanted to know — I also wanted to know what was on Weibo, so I could keep up with my social circles.

That question planted the seed for What’s on Weibo: the simple curiosity of “What are people talking about?” What TV series are popular? What jokes and controversies are everyone discussing (but that I never fully grasped)? I wanted to get a sense of an online world that was, in many ways, intangible to outsiders — including myself. As I had moved back to Europe by then, it was also a way for me to stay connected to those everyday conversations unfolding online in China.

With scissors, glue, and some paper, I started sketching out what a future website might look like.

Papercrafting the idea for a website named ‘What’s on Weibo’ in 2012.

And in March 2013, after doing my best to piece it together, I launched What’s on Weibo and began writing — about all kinds of trends, like the milk powder crisis, about China’s many unmarried “leftover men” (shengnan 剩男), and about the word of the moment, “Green Tea Bitch” (lǜchá biǎo 绿茶婊) — a term used to stereotype ambitious women who act sweet and innocent while being seen as calculating or cunning.

2. From Weibo to the Taobao Moment: China’s Mobile Social Era: (2010–2019)

Around 2014–2015, people started saying Weibo was dead. In fact, it hadn’t died at all — some of its most vibrant years were still ahead. It had simply stumbled into the mobile era, along with China’s entire social media landscape.

As mobile internet became more widespread and everyone started using WeChat (launched in 2011), new mobile-first platforms began to emerge.2 In 2012–2013, for example, apps like Toutiao and Xiaohongshu (小红书, RED) were launched as mobile community platforms. With the rapid rise of China’s new tech giants — Bytedance, Meituan, and Didi — a new mobile era was blossoming, leaving the PC-based social media world far behind.

Spending another summer in Beijing in 2014, I called it the “Taobao Moment” — Taobao being China’s most successful online marketplace, a platform for buying and selling practically everything from clothes and furniture to insurance and even Bitcoins. At the time, I thought Taobao captured everything Beijing was at that moment: a world of opportunities, quick decisions, and endless ways to earn and spend money.

On weekends, some of my friends would head to the markets near the Beijing Zoo to buy the latest dresses, purses, jeans, or shoes. They’d buy stock on Saturday, do a photo shoot on Sunday, and sell the goods online by Monday. You could often spot young people on the streets of Beijing staging their own fashion shoots for Taobao — friends posing as models, Canon cameras in hand.

During that period, What’s on Weibo gradually found its audience, as more people became curious about what was happening on Chinese social media.

Around 2016, Weibo entered another prime era as the “celebrity economy” took off and a wave of “super influencers” (超级红人) emerged on the platform. Papi Jiang stood out among them — her humorous videos on everyday social issues made her one of China’s most recognizable online personalities, helping to drive Weibo’s renewed popularity.

Witty Papi Jiang was a breath of fresh air on Weibo in 2016.

People were hooked on social media. Between 2015 and 2018, China entered the age of algorithm- & interest-driven multimedia platforms. The popularity of Kuaishou’s livestreaming and Bytedance’s Douyin signaled the start of an entirely new era.

3. The New Social Era of AI-fication and Diversification (2020–Current)

China’s social media shifts over the past 25 years go hand in hand with broader technological, social, and geopolitical changes. Although this holds true elsewhere too, it’s especially the case in China, where central leadership is deeply involved in how social media should be managed and which direction the country’s digital development should take.

Since the late 2010s, China’s focus on AI has permeated every layer of society. AI-driven recommendation systems have fundamentally changed how Chinese users consume information. Far more than Weibo, platforms like Douyin, Kuaishou, and Xiaohongshu have become popular for using machine-learning algorithms to tailor feeds based on user behavior.

China’s social media boom has put pressure on traditional media outlets, which are now increasingly weaving themselves into social media infrastructure to broaden their impact. This has blurred the line between social media and state media, creating a complex online media ecosystem.

At the same time, it’s not just AI and media convergence that are reshaping China’s online landscape — social relationships now dominate both information flows and influence flows. 3 Not everyone is reading the same headlines anymore; people spend more time within their own interest-based niches. It’s no longer about microblogging but about micro-communities.

China now has 1.12 billion internet users. Among new users, young people (aged 10–19) and the elderly (60+) account for 49% and nearly 21%, respectively. The country’s digital environment has never been more lively, and social media has never been more booming.

As a bit of a dinosaur in China’s social media world, Weibo still stands tall — and its trending topics still matter. But the community that was once at the heart of the Chinese internet has dispersed across other apps, where people now engage in more diverse ways than ever.

In China, I notice this shift: where I once saw the rise of Weibo, the Taobao boom, or the Douyin craze, I now see online and offline media increasingly converging. Social media shapes real-life experiences and vice versa, and AI has become integrated into nearly every part of the media ecosystem — changing how content is made, distributed, consumed, and controlled.

In this changing landscape, the mission of What’s on Weibo — to explain China’s digital culture, media, and social trends, and to build a bridge between Western and Chinese online spaces — has stayed the same. But the name no longer fits that mission.

Over the past few years, my work has naturally evolved from Weibo-focused coverage to exploring China’s digital culture through a broader lens. The analysis and trend updates will continue, but under a new name that better reflects a time when Weibo is no longer at the center of China’s social media world: Eye on Digital China.

For you as a subscriber (subscribe here), this means you can expect more newsletter-based coverage: shorter China Trend Watch editions to keep you up to date with the latest trends, along with other thematic features and ‘Chapter’ deep dives that explore the depth behind fleeting moments.

For now, the main website will remain What’s on Weibo, but it will gradually transition into Eye on Digital China. I’ll keep the full archive alive — more than twelve years of coverage that helps trace the digital patterns we’re still seeing today. After all, the story of China’s past online moments often tells us more about the future than the trends of the day.

Thank you for following along on this new journey.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

1 Liu, Fengshu. 2011. Urban Youth in China: Modernity, the Internet and the Self. New York: Routledge, 50.

2 Mao Lin (Michael). 2020. “中国互联网25年变迁:两次跃迁,四次浪潮,一次赌未来” [25 Years of China’s Internet: Two Leaps, Four Waves, and a Gamble on the Future]. 人人都是产品经理 (Everyone Is a Product Manager), January 3. https://www.woshipm.com/it/3282708.html.

3 Yang, Shaoli (杨绍丽). 2025. “研判2025!中国社交媒体行业发展历程、重点企业分析及未来前景展望:随着移动互联网兴起,社交媒体开始向移动端转移 [Outlook for 2025! The Development History, Key Enterprises, and Future Prospects of China’s Social Media Industry: With the Rise of Mobile Internet, Social Media Has Shifted to Mobile Platforms].” Zhiyan Consulting (智研咨询), February 7. https://www.chyxx.com/industry/1211618.html.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in the comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient — we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

Eye on Digital China, by Manya Koetse, is co-published on Substack and What’s on Weibo.

Both feature the same new content — so you can read and subscribe wherever you prefer. Substack offers community features, while What’s on Weibo provides full archive access. If you’re already subscribed and want to switch platforms, just get in touch for help. Both feature the same new content — so you can subscribe or read wherever you prefer. If you’re already subscribed on one platform and would like to move your subscription over, just let me know and I’ll help you get set up.

© 2025 Manya Koetse. All rights reserved.

China Media

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Published

10 months agoon

March 30, 2025

“This man is doing God’s work. In just six hours, he eliminated all Western media propaganda about China,” Chinese influencer Li Sanjin (李三金) said in one of his videos this week. The man he referred to, allegedly doing ‘God’s work,’ is the American YouTuber and online streamer Darren Watkins, better known as IShowSpeed or Speed, who visited China this week and livestreamed from various locations.

With 37 million followers on his YouTube account, Watkins’ visit hasn’t exactly flown under the radar. His streams from China have already accumulated over 17.5 million views on YouTube alone, and he also became the talk of the week on Chinese social media.

In China, the 20-year-old IShowSpeed is known as Jiǎkànggē (甲亢哥), or “Hyper Bro,” since the immensely popular YouTube star is known for being highly energetic.

Although IShowSpeed is originally known for soccer and gaming-related content, he’s been streaming live from various countries over the past year, from Ecuador to Bolivia, from Australia to Indonesia, from Romania to Japan, and also from the Netherlands, where a mob of fans harassed the YouTuber to such an extent that the influencer fled and panicked, until the police intervened and asked him to shut down the livestream for safety reasons — which he did not comply with.

It was not the only time IShowSpeed’s visit got chaotic. He also got into trouble during livestreams from other countries. While streaming from Norway, he injured his ankle and was swarmed by a crowd while trying to get out. In Greece and Indonesia, he had to ask for police support as well. In Thailand, he crashed a tuk-tuk into a temple wall.

In China, IShowSpeed’s livestreams went far more smoothly, and netizens, state media, and other official channels raved about his visit and its favorable portrayal of the country and its culture.

🔹 Symbol of Cultural Exchange & Positive Diplomacy

“Jiǎkànggē” became one of the viral terms of the week, on Weibo, Kuaishou, Douyin, and Toutiao. During his China trip, the livestreamer hit several YouTube milestones — not only breaking the 37 million subscriber mark while on stream, but also surpassing the magic number of 10 million views in total.

Watkins, also known for being (sometimes aggressively) loud and chaotic, suddenly emerged as a symbol of cultural exchange and positive diplomacy. The past week saw hashtags such as:

#️⃣”IShowSpeed gives young foreigners a full-window view into China” (#甲亢哥给国外年轻人开了全景天窗#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed’s Shanghai livestream breaks Western filter on China” (#甲亢哥上海直播打破西方对中国滤镜#)

#️⃣”American influencer IShowSpeed amazed by stable wifi on China’s high-speed train” (#美国网红甲亢哥被高铁稳定网络震惊#)

#️⃣”IShowSpeed praised deep tried tripe for being incredibly delicious” (#甲亢哥赞爆肚太好吃了#), or

#️⃣ “IShowSpeed bridges the cultural divide” (#甲亢哥弥合文化鸿沟#).

While in Chinese media, Watkins was lauded for shining a positive light on China, this message was also promoted on English-language social media, where he was praised by the Chinese embassy in the US (#驻美大使馆称赞甲亢哥中国行#), writing:

Post by Chinese Embassy in the US on X, March 26.

“This 20-year-old American internet star is bridging cultural gaps through digital means and creating new channels for foreign audiences to better understand China.”

So what exactly did IShowSpeed do while in China?

On March 24, Watkins livestreamed from Shanghai. He wandered around the city center, visited a KFC, danced with fellow streamers, stopped by a marriage market, ate noodles, played ping-pong, had hotpot, joined a dragon dance group and got acquainted with some traditional Chinese opera performance, and walked along the Bund.

On March 26, he streamed from Beijing, starting in Donghuamen before briefly entering the Forbidden City—dressed in a Dongbei-style floral suit. He later took a stroll around Nanluoguxiang and the scenic Houhai lake, rode a train, and finally visited the Great Wall, where he did backflips.

In his stream on March 28, Watkins traveled to Henan to visit the famous Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng, hoping to find a master to teach him kung fu. He trained with Shaolin monks—footage that quickly went viral.

Lastly, on March 29, he opened his own Weibo account and published his first post. On Douyin, he shared a video of his visit to Fuxi Mountain in Zhengzhou, featuring the popular “Stairway to Heaven” tourist spot.

On social media, many viewers were captivated by the content. One major talking point was the remarkably strong internet connection that allowed him to livestream for six-hour stretches without losing signal in Shanghai. (Though his Beijing stream started off patchier, the drop was minor.) For many, it symbolized the quality of China’s 5G services.

Foreign viewers also praised how safe, friendly, and clean the country appeared, and how his streams highlighted various aspects of Chinese culture—from everyday people to traditional arts and local cuisine.

🔹 Telling & Spreading China’s Stories Well

It is no wonder the success of the Jiǎkànggē livestreams is celebrated by Chinese official media in an age where China’s foreign communication aims to increase China’s international discourse power, shaping how the world views China and making that image more credible, more respectable, and more lovable.

That’s not just an observation — it’s an official strategy. Introduced by Xi Jinping in 2013, “Telling China’s Story Well” (“讲好中国故事”) is a political slogan that has become a key propaganda strategy for China and continues to be a priority in finding different ways of promoting Chinese culture — new ways of telling China’s story in the social media age – while countering Western dominant narratives about China.

In increasingly digitalized times, it is not just about telling China’s story well, but also spreading China’s message effectively — preferably through genuine and engaging stories (Cai 2013; Qiushi 2021).

Especially young, non-official ‘storytellers’ can make China’s image more relatable and dynamic. One major example, highlighted in a 2022 case study by Zeng Dan (曾丹), is Chinese influencer Li Ziqi (李子柒). You’ve probably heard of her, or seen snippets of her videos: she creates soothing, cinematic content depicting China’s countryside lifestyle, focused on cooking, crafts, and gardening. With 26 million followers on YouTube, Li Ziqi became a viral sensation who successfully communicated an authentic and appealing ‘China story’ to a broad global audience.

Li Ziqi in one of her YouTube videos.

Although the calm and composed Li Ziqi and the loud, chaotic IShowSpeed couldn’t be more different, they have some things in common: both have large international fanbases, including their millions of YouTube subscribers; they offer perspectives that differ from Chinese state media or official channels; and they have the capacity not just to tell China’s story well, but to spread it effectively through videos and livestreams.

🔹 Spontaneous Stream or Scripted Propaganda?

IShowSpeed’s China streams have triggered a wave of responses from fans and viewers, sparking discussions across international social media and even making newspaper headlines.

In English-language online media spheres, there appear to be a range of perspectives on Watkins’ China trip:

📌 One prominent view—also echoed by various foreign influencers on YouTube and other platforms—is that IShowSpeed’s visit counters “Western media lies” about China and has successfully shown the “real China” through his livestreams. The Shanghai-based media outlet Radii claimed that “IShowSpeed’s China Tour is doing more for Chinese Soft Power than most diplomats ever could.”

📌 Others challenge this narrative, questioning which dominant Western portrayals of China IShowSpeed has actually disproven. Some argue that the idea of China being a “bleak place with nothing to do where people live in misery” is itself a false narrative, and that presenting IShowSpeed’s livestreams as a counter to that is its own form of propaganda (see: Chopsticks and Trains).

📌 There are also those who see Watkins’ trip as a form of scripted propaganda. To what extent were his livestreams planned or orchestrated? That question has become one of the central points of debate surrounding the hype around his visit.

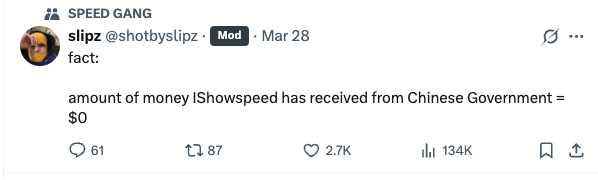

These rumors have been addressed by cameraman Slipz (@shotbyslipz), who took to X on March 28, 2025. Slipz posted that the team is “(..) not making political content, not any documentary and no journalism,” and later added: “Fact: amount of money IShowSpeed has received from Chinese Government = $0.”

But does the fact that IShowSpeed did not receive money from the Chinese government mean that it wasn’t also a form of China promotion?

➡️ Organized — it definitely was. Any media trip in China has to be. IShowSpeed would have needed a visa, he had translators with him, and throughout the streams it’s evident that local guards and public security officers were present, walking alongside and helping to keep things under control, especially in crowded areas and at major tourist spots — from Nanjing Road in Shanghai to an entire group of guards seemingly accompanying the entourage in the Forbidden City.

One logistical “advantage” to his visit was the fact that YouTube is blocked in China. While some Chinese fans do bypass the Great Firewall to access the platform, IShowSpeed remains far less known in China than in many other countries — a factor that likely contributed to how smoothly the streams went and helped prevent chaos. The team also launched a Douyin account during the trip, where he now has over two million followers. (To stream directly to their 37 million followers on YouTube, Watkins’ team either needed a VPN to access WiFi or had arranged roaming SIM cards to stay connected.)

➡️ Was it staged? Many parts clearly weren’t: casual public conversations, spontaneous barber visits in both Shanghai and Beijing (with barbers looking unsure of how to handle the situation), and wholesome fan encounters. There was even a moment when Watkins walked into a public restroom and forgot to mute the sound.

But other parts of the trip were undeniably staged — or at least framed to appear spontaneous. When visiting a marriage market in Shanghai, for instance, two actors appeared, including one woman with a sign stating she was looking for someone “capable of doing backflips.”

When Watkins took a “random” ride in what was described as the fastest car in China — the Xiaomi SU7 Ultra — the vehicle appeared to be conveniently parked and ready.

Similarly, when the streamer “ran into” Chinese-American TikTok influencer Miles Moretti (李美越) in Beijing, it turned out to be the person who would give him the now-iconic bright Dongbei flower suit and accompany him on his journey.

The ping-pong, the kung fu, the Peking opera, the hotpot, the Forbidden City tour — it all plays into the kinds of experiences that official channels also like to highlight. While likely planned by Watkins’ team in coordination with local partners, it was all far more orderly and tourism-focused than, for example, Watkins’ chaotic visit to the Netherlands.

Watkins and his entourage were also well-informed about the local dos and don’ts. At one point, Watkins even mentions “following the rules,” and when Moretti tells him mid-stream that “somebody very important lives on our left,” Watkins asks “Who?” — but the camera zooms out and the question goes unanswered, suggesting they may have been reminded that certain names or topics were off-limits (judge the moment for yourself here).

The livestream didn’t always go exactly the way Watkins wanted, either. When he attempted to take more random walks around the city, the crew appeared to be informed that some areas were off-limits, and he was asked to return to the car to continue the trip (clips here and here).

🔹 The “Nàge” Song

One major talking point surrounding IShowSpeed’s China livestreams was “the N-word.” No, not that N-word — but the Chinese filler word “nàge” or “nèige” (那个). Like “uhm” in English or “eto” in Japanese, “nàge” is a hesitation marker commonly used in everyday Mandarin conversation. It also functions as a demonstrative pronoun meaning “that.”

The word has previously stirred controversy because of its phonetic resemblance to a racial slur in English. In 2020, an American professor at the University of Southern California’s Marshall School of Business was even temporarily suspended after using the word during an online communications class — some students misunderstood its context and took offense.

The word — and the song “Sunshine, Rainbow, White Pony” (阳光彩虹小白马) by Chinese singer Wowkie Zhang (大张伟), which repeatedly features the word nàge in its chorus — popped up multiple times during Watkins’ trip. The catchy tune essentially became the theme song of his visit.

The first nàge moment actually already appeared within the first five minutes of Watkins’ Shanghai stream, when a Chinese comedian approached him on the street, trying to recall a joke. “What?!” Watkins reacted, with laughter in the background. “That’s not a joke, you said n**! It’s my first five minutes in China!” he exclaimed, before patting the man’s back in a friendly gesture, clearly not offended.

🔄 It resurfaced again within the first hour when Watkins visited a marriage market and one of the performers sang the Wowkie Zhang song. Watkins initially acted shocked, then demanded they sing it again — only to burst out laughing and start singing along.

🔄 Later, he sang the song again with a street saxophonist and encouraged others to join in.

🔄 At other moments, he played up the drama again, feigning anger when a crowd broke into the chorus, and it became a recurring gag throughout the streams.

These incidents all seem staged. One of the main reasons Watkins is known to many netizens in China is because of an older video clip showing his exaggerated reaction to the nàge song — dating back to at least 2022. So while it may have looked spontaneous, Watkins was already familiar with the word and the viral song long before his China trip.The attention given to the nàge ‘controversy’ was likely amplified for views and engagement.

While Watkins was clearly in on this part of the show — as with others — he also seemed genuinely, and at times amusingly, unaware of many things in China. He repeatedly referred to RMB as “dollars,” mistook elderly women for retired YouTube streamers, and even assumed that a woman livestreaming near the Forbidden City was reading his chat and trying to collaborate with him — although she seemed totally uninterested and was just minding her own business.

🔹 A Win-Win Situation

In the end, IShowSpeed’s visit highlighted two sides effectively doing their job. Watkins and his team successfully arranged a YouTube trip that generated high ad revenue, attracted millions of new subscribers, and boosted his brand and global fame.

On the Chinese side, there was clearly coordination behind the scenes to ensure the trip went smoothly: avoiding controversy, ensuring safety, and showcasing positive aspects of Chinese culture. From traditional opera and kung fu to ping pong, IShowSpeed’s content gave center stage to the kinds of cultural highlights that align closely with China’s official narratives and tourism goals. Even if the government didn’t pay the YouTuber directly, as his team has emphasized (and there’s no reason to doubt them), the trip still fit seamlessly into China’s soft power strategy.

IShowSpeed’s China visit has created a unique media moment that resonates for several reasons: it’s the encounter of a young modern American with old traditional China; it is a streamer known for chaos visiting a nation known for control. And it brings different benefits to both sides: clicks and ad revenue for IShowSpeed, and free foreign-facing publicity for China.

No, IShowSpeed didn’t undo years of critical Western media coverage on China. But what his visit shows is that we’ve entered a phase where China is becoming more skilled at letting others help tell its story — in ways that resonate with a global, young, online audience. He didn’t do “God’s work.” He simply did what he always does: stream. And with China’s help, he streamed China very well.

There’s so much more I want to share with you this week — from Chinese reactions to the devastating Myanmar earthquake, to a recent podcast I joined with Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf (link in Dutch, for those interested). But it also happens to be my birthday today, and I’m really hoping to still grab some birthday hotpot — so I’ll wrap this up here. I’ll keep you informed on the other trends in the next newsletter.📨.

Best,

Manya

(@manyapan)

References:

Cai, Mingzhao 蔡名照. 2013. “Telling China’s Stories Well and Spreading China’s Voice: Thoroughly Studying and Implementing the Spirit of Comrade Xi Jinping’s Important Speech at the National Conference on Propaganda and Ideological Work [讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音——深入学习贯彻习近平同志在全国宣传思想工作会议上的重要讲话精神].” People’s Daily 人民日报, October 10. http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1010/c1001-23144775.html. Accessed March 29.

Qiushi 求是网. 2021. “Xi Jinping: Telling China’s Story Well, Spread China’s Voice Well [习近平:讲好中国故事,传播好中国声音].” Qs Theory, June 6. http://www.qstheory.cn/zhuanqu/2021-06/02/c_1127522386.htm. Accessed March 29.

Zeng Dan 曾丹. 2022. “How to Tell China’s Story Well: Taking Li Ziqi as an Example [如何讲好中国故事——以李子柒为例].” Progress in Social Sciences 社会科学进展 4 (1): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.35534/pss.0401002.

What’s Featured

Quite terrifying and interesting, as this trending story touched upon so many different issues.

What started as a single snarky comment on Weibo spiraled into an online witch hunt, exposing not just some dark sides of online Kpop fandom but also, most importantly, the vulnerabilities in China’s digital privacy.

Read the story, the latest by Ruixin Zhang 👀

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment7 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West