China Arts & Entertainment

How Chinese Netizens Boosted the Buzz for the ‘Creation of the Gods’ Blockbuster

Despite initial low expectation, this Chinese ‘Lord of the Rings’ has now garnered a devoted online community of fans who are helping to boost its success.

Published

11 months agoon

It has become a major summer box office hit in China: Creation of the Gods I. Despite its initial lackluster performance, audiences raved about the mix of traditional Chinese mythology and high-tech industrialized cinema, and a loyal online community of fans boosted its ticket sales.

Early this week, the Weibo hashtag “Creation of the Gods I Breaks 2 Billion Yuan [US$275M] in Box Office” (#封神第一部票房破20亿#) became a trending topic on Weibo, followed by a hashtag celebrating raking in 2.2 billion [US$302M] on Friday (#封神第一部票房破22亿#), showcasing the remarkable success of Creation of the Gods I: Kingdom of Storms (封神第一部:朝歌风云) in both Chinese cinemas and across social media platforms.

Together, the hashtags have amassed an impressive 230 million views to date, underscoring the growing popularity of this summer box office sensation.

Directed by Chinese film director Wuershan (乌尔善), Creation of the Gods I: Kingdom of Storms stands as the initial film within the trilogy of the fantasy epic Creation of the Gods, also known as Fengshen Trilogy (封神三部曲).

The mythological epic is considered the most ambitious and expensive production in Chinese film history with a planned budget of 3 billion yuan (approximately US$410 million).

The film, which was officially released on July 20th, achieved its box office milestone 25 days after its release. The success of Creation of the Gods I can largely be attributed to the collaborative efforts of the production team and a dedicated group of fans who volunteered to promote the film online, a phenomenon referred to as zìláishuǐ (自来水).

Zìláishuǐ (自来水) literally means ‘tap water’ but it is a label for those netizens who spontaneously promote a film or artist without getting paid for it.

The three characters, 自来水, are actually an abbreviation of the term 自发而来的网络水军 (zìfāérlái de wǎngluò shuǐjūn: “self-organized internet water army”).

This term has emerged on Chinese social media in recent years, signifying a group of individuals who willingly promote films or television series out of love and admiration. Their actions are driven by personal enthusiasm and passion. Unlike those who are paid to promote something, these ardent fans invest their own time and effort into amplifying the presence of their favorite films or shows.

This concept first gained prominence within the fan community of the film Wolf Warrior (战狼) in 2015. It gained broader recognition with Monkey King: Hero Is Back (西游记之大圣归来) later that same year when zìláishuǐ successfully influenced numerous cinemas to increase showings for the animated movie. Earlier this year, zìláishuǐ once again played a crucial role in boosting the popularity of The Wandering Earth II (流浪地球2) upon its release.

Rocky Start for a Multi-Billion-Dollar Film

The origins of the Fengshen Trilogy can be traced back to an initial pinghua (平话) story – which laid the foundation for later written narrative forms in China, – namely King Wu’s Campaign Against [King] Zhou (武王伐纣平话), that emerged sometime between the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties, as well as the Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), a novel from the Ming (1368-1644) dynasty.

This captivating narrative delves into the history of the Shang (c. 1600-c. 1046 BC) and Zhou (c. 1046-771 BC) dynasties, intricately weaving together folklore, legends, and a variety of mythical beings and creatures.

The official movie poster.

Wuershan reportedly came up with the idea for the movie after watching The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring in 2001 and publicly shared his intention to turn the Fengshen story into a film in 2012. The project officially commenced in June 2014.

From February 2017 onwards, a global audition was held to select the lead actors and actresses, who then underwent 6-8 months of specialized training. The filming started on August 2018, and concluded in January 2020.

The narrative of Fengshen holds tremendous popularity in China. Nevertheless, this extensive familiarity might actually present a challenge when it comes to triggering the audience’s interest. Past mythological films produced in China have often left viewers with exceedingly low expectations – or even a lack of expectations altogether – for this genre of Chinese cinema.

The challenges encountered by Wuershan and his team were amplified by the three-year-long pandemic and the investment issues of the film’s primary production company, Beijing Culture. The pandemic introduced uncertainty about the film’s release, while Beijing Culture, the primary investor, faced complications due to its involvement in actress Zheng Shuang’s project. Zheng’s reputation had already taken a significant hit when she was accused of abandoning her two surrogate babies in the US, followed by substantial fines for tax evasion (read more).

Although the filming concluded, the movie’s release date was pushed back, prompting concerns about the film’s quality and noticeably dampening the expectations and excitement among Chinese netizens. In June 2023, the announcement of the film’s official release date also failed to generate significant attention or interest among netizens.

At the early stages of promoting the film, the movie’s marketing team adopted a strategy in which they mostly highlighted the young, good-looking, and muscular actors starring in the film. But this approach made some netizens believe that the film had to rely on such visuals to attract audiences because its overall quality was just not up to par.

Based on data from the Chinese ticketing platform Maoyan, Creation of the Gods I garnered a modest box office earnings of slightly over 49 million yuan (US$6.7M) on its opening day, positioning it in the eighth spot among other films that were launched around the same time. This outcome was not just quite disappointing for a project that had received a substantial investment of 3 billion yuan – it was actually pretty disastrous.

Captivating the Hearts of Moviegoers

In spite of its tumultuous production journey and initial cautious response from Chinese moviegoers, as the film continued to be screened in theaters, an increasing number of netizens began to develop a genuine fondness and admiration for Creation of the Gods I.

1: New Portrayal of Su Daji

The presentation of the storyline, especially the reinterpretation of the renowned character Su Daji (苏妲己), garnered praise from moviegoers.

In the original story of Investiture of the Gods, Su Daji was held responsible for the downfall of the Shang Dynasty due to her seduction of Yin Shou (殷寿), the King of the Shang Dynasty. This fateful enticement ultimately metamorphosed him into a ruthless ruler, leading to the demise of the dynasty.

Within China, an ingrained idiomatic expression places responsibility on women for unfortunate occurrences, known as “a beauty that brings disaster” (红颜祸水), and Su Daji has long been emblematic of this notion. However, Wuershan and his screenwriting team chose to diverge from this perspective in the film. Instead, the movie portrays Su Daji as a manifestation of Yin Shou’s ambitious nature. It underscores that Su Daji wasn’t the catalyst for the dynasty’s downfall; rather, Yin Shou himself was responsible for his own downfall.

Although not everyone agrees with this new portrayal of Su Daji, the controversy around the character’s representation has brought greater attention to the film.

2: Fresh Faces in China’s Cinema

Another factor contributing to Creation of the Gods I‘s success in capturing the affection of early moviegoers is the commitment exhibited by both the younger and more seasoned actors and actresses, whether in leading roles or supporting positions.

The majority of actors and actresses who assumed key roles in the film were newcomers to the entertainment industry, introduced through a global audition process. This extensive search encompassed around 15,000 individuals worldwide, culminating in the selection of over 30 participants for a specialized training camp.

The actors and actress before and after the training courses. Snapshots from the film’s production documentary.

Within this training program, they underwent instruction in martial arts, equestrianism, archery, drumming, ancient qin music, and a variety of cultural courses, including pre-Qin history and etiquette. These courses were devised based on the Six Arts: rites (礼), music (乐), archery (射), chariotry or equestrianism (御), calligraphy (书), and mathematics (数). These arts formed the core of education in ancient Chinese culture and were required to be mastered by students during the Zhou dynasty.

3: Costume & Set Design

The production team’s meticulous attention to detail in the costumes and set designs further increased the film’s popularity.

For example, the production team built an entire forest system ecosystem reminiscent of Tibet’s Linzhi and Motuo forests, all within a 10,000-square-meter studio in Qingdao. This was partly due to the protective status of Tibet’s forests, rendering filming scenes involving horse riding impossible. The set allegedly was so lifelike, that many butterflies and insects were attracted to the forest after it was completed.

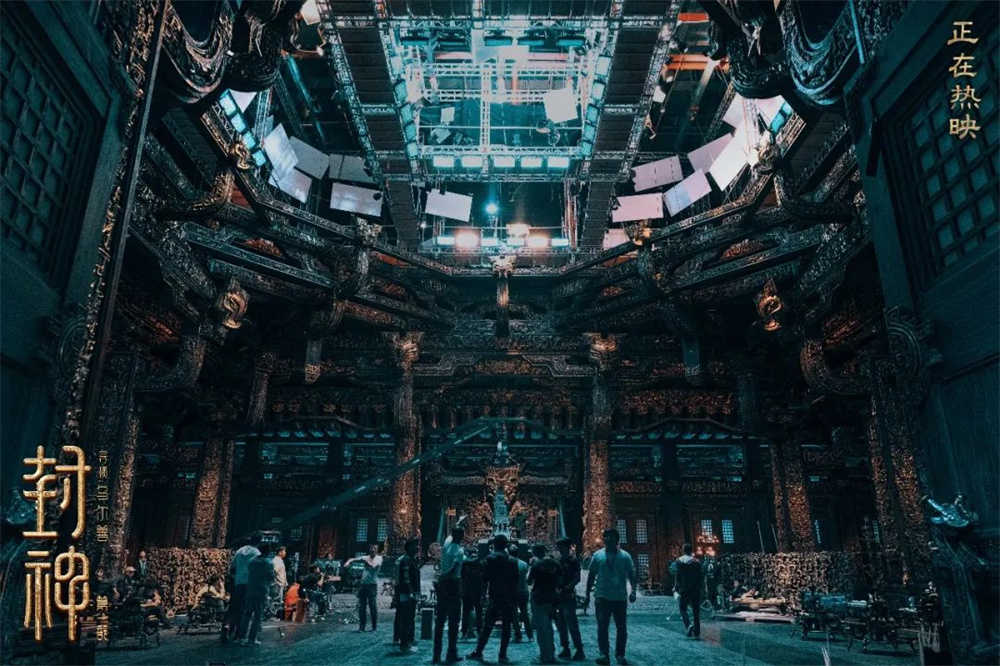

The Longde Hall set, via The Paper.

Similar stories also includes the construction of the main set, the Longde Hall (龙德殿) which was built up by a set design team consisting of 1,500 workers, with 800 of them specializing in wood carving.

After learning all these stories behind the movie, many Chinese netizens have come to believe that the film is not as bad as initially thought. They attributed its underperformance at the box office not to its quality but to an inadequate promotional strategy and execution. In response, many have rallied to support the film.

Zilaishui to the Rescue

Lately, a big group of fresh enthusiasts for Creation of the Gods have come together on Chinese social media and are growing rapidly as a community of ‘Fengshen zìláishuǐ‘ (封神自来水): voluntary and passionate supporters and promoters of the Fengshen Trilogy.

Shui Mu Ding (@水木丁), a Chinese columnist and writer, who is also a member of the ‘Fengshen zìláishuǐ,’ shared her emotions after observing the film’s first-day box office results: “Picture yourself strolling along the beach and stumbling upon a beached whale. You may not have the power to help it, but would you just turn around and leave? It seems impossible to let go.”

She then wrote an article and published it on WeChat and Weibo, recommending this film to her readers and followers. Some people questioned if she was paid for it, but she said she did this “simply because I want to.”

Simultaneously, other members of the ‘Fengshen zìláishuǐ‘ community are also contributing to broaden the film’s impact through various approaches.

For example, they use the content of the film to create memes on social media.

One of the trending memes is the “God Bless You” meme created by netizens. The meme features Chen Kun’s role in the film – Yuanshi Tianzun, one of the highest deities in Taoism.

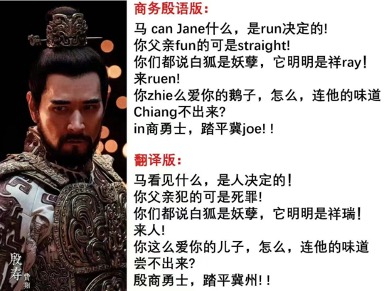

Due to actor Fei Xiang’s (费翔) prolonged stay in English-speaking countries, he carries a unique accent when speaking Mandarin. Chinese internet users have noticed this and discovered that in his dialogue, there are certain pronunciations resembling English words. For this reason, together with some word jokes in Chinese, this kind of ‘Chinglish’ (‘Yinglish’ 商务殷语) has become a source of online banter.

They also cleverly “hijack” ongoing trending topics linked to the actors involved in the film, even when these subjects weren’t directly linked to the film itself. By employing a clickbait approach or crafting posts reminiscent of gossip news narratives, their ultimate goal is to persuade netizens who viewed this hashtag to learn more about the film and, ideally, entice them to go to the cinemas to see the movie.

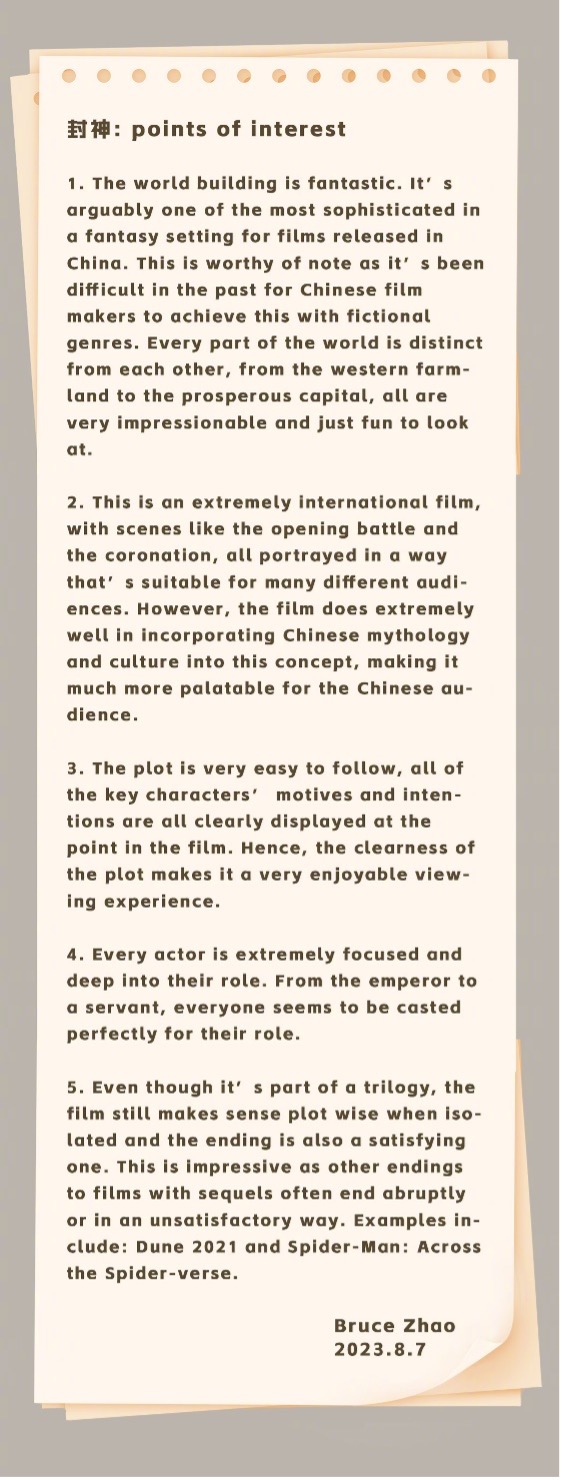

A review penned by the stepson of Chinese actress Chen Shu (陈数). He composed the review in both Chinese and English, intending to recommend the movie to people outside of China.

Then there are those people sharing their experiences after viewing the movie in the cinema and posting them on different social platforms. Some fans even choose to watch the film in theaters twice, three times or even more, pondering over details and sharing their discoveries online, to showcase their support for the film.

Embracing a New Era in the Industrialization of China’s Film Industry

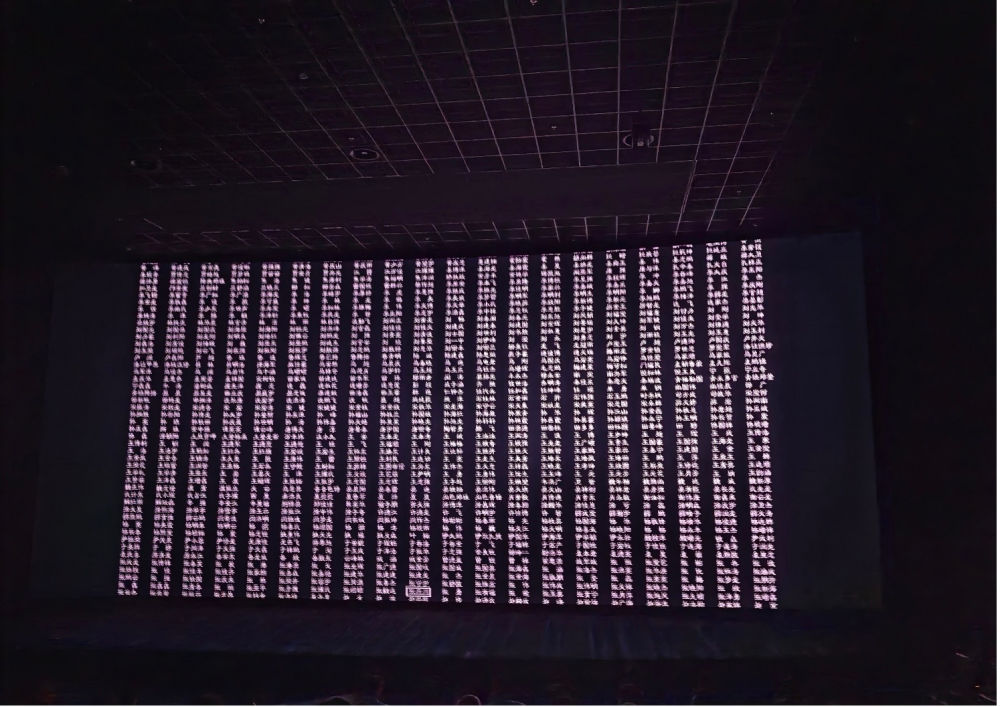

Among the many reviews shared by Fengshen zìláishuǐ, the credits list at the end of the film, just before the bonus scene, keep poppping up. This extensive roster of names, scrolling across the screen for about three minutes, shows the immense scale of this challenging project, resonating deeply with many moviegoers and sparking discussions on the industrialization of Chinese films.

As highlighted in prior interviews, director Wuershan possesses a clear vision for enhancing and refining Chinese film production. His ideas encompass streamlining film production processes by genre, implementing structured and methodical approaches to oversee every facet of filmmaking, and seamlessly integrating cutting-edge technologies.

Wuershan talking about producing the movie.

These principles have been seamlessly woven into the production of the Fengshen Trilogy, setting new standards for the industrialization of China’s film realm.

For instance, prior to actual filming, Wuershan conducted multiple animation previews and rehearsals, aligning his team with his creative vision and mitigating potential losses arising from miscommunication. This approach not only trimmed shooting and editing expenses but also facilitated meticulous planning of the shooting schedule.

Given the film’s extensive utilization of visual effects and reliance on blue screen technology, director of photography Wang Yu (王昱) and his team devised an ingenious technique to craft an expansive screen. They ingeniously repurposed excavator buckets into blue panels, collaborating with the excavator team to erect the blue screen as needed. Through precise control of various angles, they erected a sprawling screen wall.

In another instance of production innovation aimed at standardizing filming procedures, the production team veered away from conventional boxed meals and fast food, instead establishing an actual “Fengshen Canteen” to cater to their workforce of 8000 members, strictly following China’s food safety regulations.

In his quest to explore new ways to improve China’s movie industry industrialization, Wuershan joins the ranks of other directors such as Guo Fan (郭帆) (The Wandering Earth 2) or Chen Sicheng (陈思诚) (Lost In The Stars). They’re all dedicated to innovating film processes across various genres by melding Hollywood knowledge with their own filmmaking expertise to bolster China’s film industry. Guo Fan also visited the set of Fengshen Trilogy to learn from the filming process.

This idealism and drive to improve China’s film industry at large has also resonated with Fengshen zìláishuǐ, futher motivating them to continue their efforts in promoting high quality Chinese films like Creation of The Gods

For now, some fans are already concerned about how their beloved “domestically produced masterpiece” will perform in the international market. But most zìláishuǐ are still busy to promote the movie on Chinese social media and further helping to grow its box office numbers, paving the way for the release of the first and second films of the trilogy during the upcoming summer vacations in China – next year and the year after. If all goes well, we’ll know what they’ll do next summer.

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Edited for clarity by Manya Koetse.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Wendy Huang is a China-based Beijing Language and Culture University graduate who currently works for a Public Relations & Media software company. She believes that, despite the many obstacles, Chinese social media sites such as Weibo can help Chinese internet users to become more informed and open-minded regarding various social issues in present-day China.

Also Read

China Arts & Entertainment

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

“I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like listening to Alicia Keys.” Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers.

Published

2 months agoon

May 17, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Besides memes and jokes, Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers on Chinese social media.

In May, while the whole of Europe was gripped by the Eurovision Song Contest frenzy, Chinese audiences were eagerly anticipating the return of their own beloved singing competition, Singer 2024 (@湖南卫视歌手), formerly known as I Am a Singer (我是歌手).

The show, introduced from South Korea’s MBC Television and popular in China since 2013, only features professional singers who have already made a name for themselves.

Rather than watching unknown aspiring singers who are hoping to be discovered in many singing competitions, such as Sing! China, Singer 2024 gives audiences a show filled with professional and often stunning show performances by established names in the entertainment industry.

Since 2013, renowned singers from China and abroad have appeared on the show, including Chinese vocalist Tan Jing (谭晶), British pop singer Jessie J, and the late Hong Kong pop diva Coco Lee. However, no season managed to create as many waves as the 2024 season did, dominating all social media trending topics overnight.

So, what exactly happened?

COMPETING WITH FOREIGNERS

“The difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival”

In early May, the pre-show promotion of Singer 2024 was already buzzing on Chinese social media after a list of featured singers appeared on Weibo, including big names such as American singer-songwriter Bruno Mars, Korean-New Zealand singer Rosé from Blackpink, and Japanese diva LiSA.

Although Singer previously had many foreign singers on the show, this international celebrity lineup still caused a stir.

On the day of the first episode, only two foreign singers were announced to appear on the show: young Moroccan-Canadian singer Faouzia and the Grammy-nominated American singer-songwriter Chanté Moore. The other contestants were all Chinese singers who are already well-known among Chinese audiences. Because many people were unfamiliar with the two foreign singers, they joked that the winner of this season was already set in stone; surely it would be the famous Chinese singer Na Ying (那英), known for her beautiful voice.

However, that first episode surprised everyone as the two foreign singers, Faouzia and Chanté Moore, showed outstanding vocal skills. This not only startled many viewers but also made the Chinese contestants uneasy. Several experienced Chinese singers apparently were so unnerved after watching Faouzia and Chanté Moore’s performance that their voices trembled when singing.

Since the show was broadcast live – without post-production editing or autotune – audiences got to hear the actual vocal capabilities and see performers’ genuine reactions. It seemed undeniable that the foreign contestants did much better in terms of vocals and stage presence than the Chinese ones. Some online commenters even said that the gap between Chinese and foreign singers’ levels was like “the difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival” [a local Chinese music festival].

Chinese online influencer Yongkai (@陈咏开165) shared screenshots of Chanté Moore’s backstage reactions during the show. The American celebrity seemed puzzled when hearing the somewhat underwhelming performance by Chinese singer Yang Chenglin (楊丞琳), and she appeared much more positive when Na Ying sang.

This noteworthy scene, coupled with Chanté’s comments during an interview saying that she thought the Chinese production team had invited her on the show to be a judge, turned the entire show into a display of foreign singers outshining the Chinese contestants.

By the end of the first episode, Chanté Moore and Faouzia unsurprisingly ranked first and second, with Na Ying in third place.

After the show, some online commenters jokingly pointed out that Na Ying, being of Manchu descent like the rulers of China during the Qing Dynasty, showed some similarities to Empress Dowager Cixi’s defiance against Western colonizers in the way she “single-handedly took up against on foreigners” on the show.

They humorously turned Na Ying’s expressions into memes resembling Empress Dowager Cixi from an old Chinese TV show, with captions like “I want the foreigners dead” (“我要洋人死”).

Others suggested finding better Chinese singers for the show who could compete with Faouzia and Moore.

“SINGING WELL” CULTURALLY COLONIZED?

“I’m in Zibo eating BBQ, I really don’t want to listen to Alicia Keys.”

Initially, discussions about the show were light-hearted and humorous, until some netizens who couldn’t appreciate the jokes began to dampen the mood and made online discussions more serious.

Zou Xiaoying (@邹小樱), a music critic with nearly two million followers, posted on social media after the show, stating that he would have never voted for Chanté Moore or Faouzia. Not only did Zou question their vocal talent, he also wondered if the aesthetic of Chinese listeners had been influenced by Western music taste to such an extent that it has been “culturally colonized” (“文化殖民”). Meanwhile, he praised the members of Beijing rock band Second Hand Rose as “national heroes” (“民族英雄”).

He wrote:

If I had three votes for the first episode of “Singer 2024,” I’d vote for Second Hand Rose, Na Ying, and Silence Wang [note: Chinese singer-songwriter and record producer Wang Sushuang 汪苏泷]. The reason I wouldn’t vote for Chanté Moore or Faouzia is because — do they actually sing so well?

Has our definition of “singing well” perhaps been colonized? Just as our modern-day use of Chinese has little to do with our classical Chinese poems, with the foundation of modern Chinese actually being translations from the 20th century, is this also a form of ‘cultural colonization’?

You must think I’m talking nonsense again. But when I listen to Chanté Moore singing “If I Ain’t Got You,” I find it too boring. I know her singing is “good,” but this “good” has nothing to do with me. If, for Chinese listeners, Chanté Moore’s “good” is the standard, then is that what we in the music industry should be working towards? Isn’t that funny? When you open QQ Music or NetEase Cloud Music, and it recommends these songs to you every day, won’t you be convinced to practice again?

Of course, I know Chanté Moore is in good shape, very relaxed. Actually all of the Chinese singers tonight were very nervous. Yang Chenglin (杨丞琳) was nervous, Na Ying was also nervous. Even a seemingly carefree band like Second Hand Rose, if you listened to the introduction of their song, [you’ll find] they were so nervous that Yao Lan, supposedly “China’s No.1 Guitarist”, was so nervous that he hit the wrong note. It was not even a fast-paced solo (…), how nervous could he be? When everyone’s so tense, the confidence of Chanté Moore and Faouzia is indeed something that East Asia can’t match. In East-Asian [entertainment] circles, represented by China/Japan/Korea, our different cultural habits, upbringing, and ethnic characteristics have made it so that we don’t possess these kinds of singing abilities, even including our ways of emotional expression. I don’t know from which season it started with ‘Singer’ – and if it’s some kind of Catfish Effect (鲶鱼效应 ) – that they brought international singers with different cultural backgrounds into the competition. But this isn’t the Olympics, it’s not like Liu Xiang [刘翔, Chinese gold medal hurdler] is going to defeat opponents from the United States or Cuba. “I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like Alicia Keys.” (This line is not mine, I stole it from my WeChat friend).

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Anyway, no matter if they’re strong or not, I would never vote for the foreigner.

The comment about ‘I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like [listening to] Alicia Keys’ refers to the craze surrounding China’s ‘BBQ town’ Zibo. In Zibo, Chinese visitors like to sing, drink beer, and enjoy food together; it’s a simple and modest way of appreciating life and music, which contrasts with slick and smooth American or foreign styles of performing and singing.

Whether Zou’s criticism was for attention or genuine sentiment, it shifted the focus of the discussion from music to patriotism.

CHINESE SINGERS WITH MILITARISTIC UNDERTONES

“I volunteer to join the battle”

Amidst all this, some netizens, easily swayed by nationalist sentiments, began to seek help from the “national team” (国家队) of singers — musicians employed by national-level arts troupes — to “bring glory to the nation” and teach the foreigners a lesson. Some even questioned the intentions of the Singer 2024 TV show in inviting foreign singers to participate.

On May 12th, renowned Chinese singer and philanthropist Han Hong (韩红) posted on Weibo, fueling a wave of sentiment and support. In her post, Han Hong declared, “I am Chinese singer Han Hong, and I volunteer to join the battle,” tagging the production team of the TV show. Her invitation to join the battle quickly went viral.

Han Hong meme: “Who called for me?”

Han Hong has significant influence in the Chinese music industry and society as a whole. Her usual serious demeanor and avoidance of internet pop culture made netizens unsure whether she was joking or serious. Nevertheless, regardless of her intentions, a group of well-known singers began to volunteer via Weibo, emphasizing their identity as “Chinese singers” and using phrases with strong militaristic undertones like “fighting for the country” and “answering the call.”

Although many enjoyed this new wave of national pride in Chinese music and performers, some netizens criticized the trend of transforming an entertainment show into a nationalistic competition.

Film critic He Xiaoqin (何小沁) stated, “It’s okay to take the Qing-Dynasty-fighting-foreigners comparison as a joke, but taking it too seriously in today’s context is absurd.”

Others expressed fatigue with how quickly topics on Chinese internet platforms escalate to patriotic sentiments. To bring the focus back to entertainment, they turned “I volunteer to join the battle” (#我请战#) into a new internet catchphrase.

In response, the production team of Singer 2024 released a statement on Weibo, thanking all the singers for their self-recommendations. They emphasized the show’s competitive structure but clarified that “winning” is just one part of a singer’s journey..but that the love of music goes beyond all in connecting people, no matter where they’re from.

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Online reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among Chinese netizens.

Published

3 months agoon

April 18, 2024

The recent marriage announcement of the renowned Chinese calligrapher/painter Fan Zeng and Xu Meng, a Beijing TV presenter 50 years his junior, has sparked online discussions about the life and work of the esteemed Chinese artist. Some netizens think Fan lacks the integrity expected of a Chinese scholar-artist.

Recently, the marriage of a 86-year-old Chinese painter to his bride, who is half a century younger, has stirred conversations on Chinese social media.

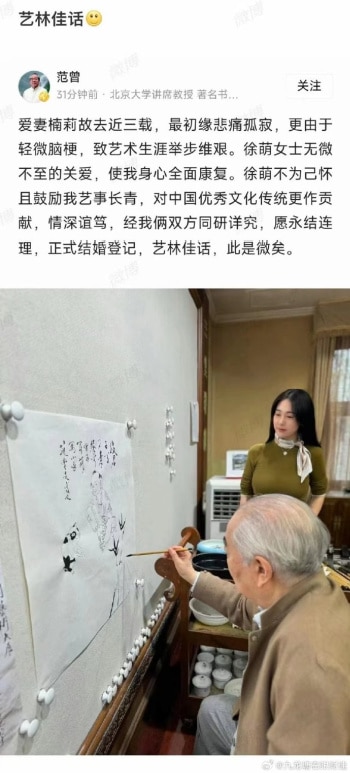

The story revolves around renowned Chinese artist, calligrapher, and scholar Fan Zeng (范曾, 1938) and his new spouse, Xu Meng (徐萌, 1988). On April 10, Fan announced their marriage through an online post accompanied by a picture.

In the picture, Fan is seen working on his announcement in calligraphic form.

Fan Zeng announces his marriage on Chinese social media.

In his writing, Zeng shares that the passing of his late wife, three years ago, left him heartbroken, and a minor stroke also hindered his work. He expresses gratitude for Xu Meng’s care, which he says led to his physical and mental recovery. Zeng concludes by expressing hope for “everlasting harmony” in their marriage.

Fan Zeng is a calligrapher and poet, but he is primarily recognized as a contemporary master of traditional Chinese painting. Growing up in a well-known literary family, his journey in art began at a young age. Fan studied under renowned mentors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, including Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Jiang Zhaohe, and Li Kuchan.

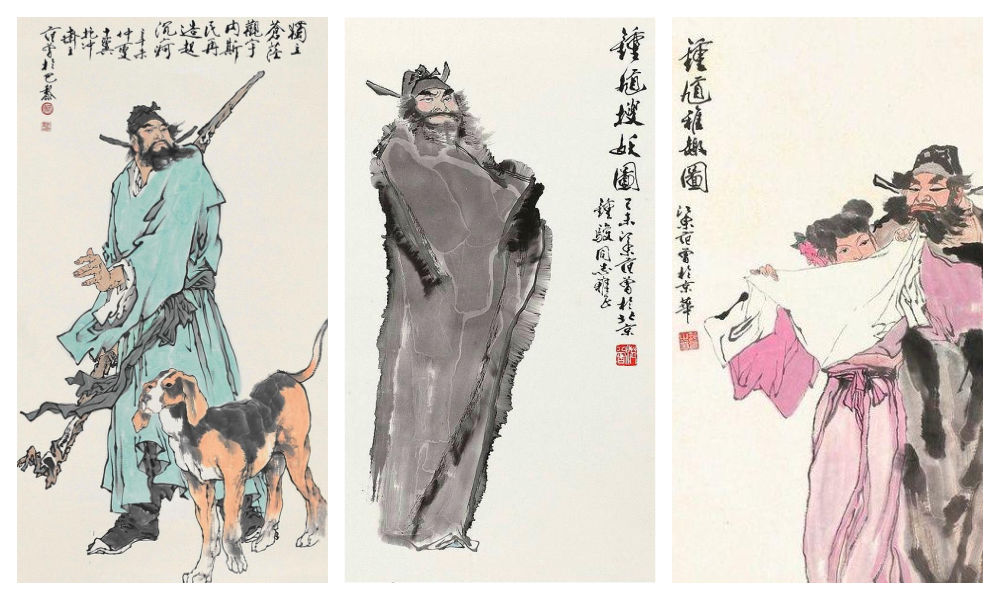

Fan gained global acclaim for his simple yet vibrant painting style. He resided in France, showcased his work in numerous exhibitions worldwide, and his pieces were auctioned at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the 1980s.[1] One of Fan’s works, depicting spirit guardian Zhong Kui (钟馗), was sold for over 6 million yuan (828,000 USD).

Zhong Kui in works by Fan Zeng.

In his later years, Fan Zeng transitioned to academia, serving as a lecturer at Nankai University in Tianjin. At the age of 63, he assumed the role of head of the Nankai University Museum of Antiquities, as well as holding various other positions from doctoral supervisor to honorary dean.

By now, Fan’s work has already become part of China’s twentieth-century art history. Renowned contemporary scholar Qian Zhongshu once remarked that Fan “excelled all in artistic quality, painting people beyond mere physicality.”

A questionable “role model”

Fan’s third wife passed away in 2021. Later, he got to know Xu Meng, a presenter at China Traffic Broadcasting. Allegedly, shortly after they met, he gifted her a Ferrari, sparking the beginning of their relationship.

A photo of Xu and her Hermes Birkin 25 bag has also been making the rounds on social media, fueling rumors that she is only in it for the money (the bag costs more than 180,000 yuan / nearly 25,000 USD).

On Weibo, reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among netizens. Despite Fan’s reputation as a prominent philanthropist, many perceive his recent marriage as yet another instance of his lack of integrity and shamelessness.

Fan Zeng and Xu Meng. Image via Weibo.

One popular blogger (@好时代见证记录者) sarcastically wrote:

“Warm congratulations to the 86-year-old renowned contemporary erudite scholar and famous calligrapher Fan Zeng, born in 1938, on his marriage to Ms Xu Meng, a 50 years younger 175cm tall woman who is claimed to be China’s number one golden ratio beauty. Mr Fan Zeng really is a role model for us middle-aged greasy men, as it makes us feel much less uncomfortable when we’re pursuing post-90s youngsters as girlfriends and gives us an extra shield! Because if contemporary Confucian scholars [like yourself] are doing this, then we, as the inheritors of Confucian culture, can surely do the same!“

Various people criticize the fact that Xu Meng is essentially just an aide to Fan, as she can often be seen helping him during his work. One commenter wrote: “Couldn’t he have just hired an assistant? There’s no need to turn them into a bed partner.”

Others think it’s strange for a supposedly scholarly man to be so superficial: “He just wants her for her body. And she just wants him for his inheritance.”

“It’s so inappropriate,” others wrote, labeling Fan as “an old bull grazing on young grass” (lǎoniú chī nèncǎo 老牛吃嫩草).

Fan is not the only well-known Chinese scholar to ‘graze on young grass.’ The famous Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), now 101 years old, also shares a 48-year age gap with his wife Weng Fen (翁帆). Fan, who is a friend of Yang’s, previously praised the love between Yang and Weng, suggesting that she kept him youthful.

Older photo posted on social media, showing Fan attending the wedding ceremony of Yang Zhenning and his 48-year-younger partner Weng Fen.

Some speculate that Fan took inspiration from Yang in marrying a significantly younger woman. Others view him as hypocritical, given his expressions of heartbreak over his previous wife’s passing, and how there’s only one true love in his lifetime, only to remarry a few years later.

Many commenters argue that Fan Zeng’s conduct doesn’t align with that of a “true Confucian scholar,” suggesting that he’s undeserving of the praise he receives.

“Mr. Wang from next door”

In online discussions surrounding Fan Zeng’s recent marriage, more reasons emerge as to why people dislike him.

Many netizens perceive him as more of a money-driven businessman rather than an idealistic artist. They label him as arrogant, critique his work, and question why his pieces sell for so much money. Some even allege that the only reason he created a calligraphy painting of his marriage announcement is to profit from it.

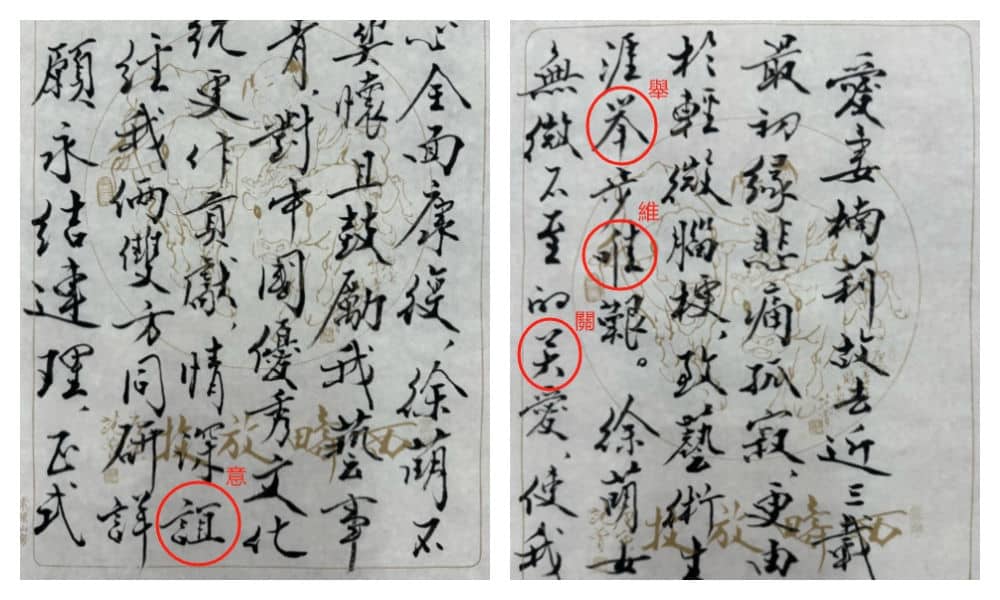

Others cast doubt on his status as a Chinese calligraphy ‘grandmaster,’ noting that his calligraphy style is not particularly impressive and may contain typos or errors. His wedding announcement calligraphy appears to blend traditional and simplified characters.

Netizens have pointed out what looks like errors or typos in Fan’s calligraphy.

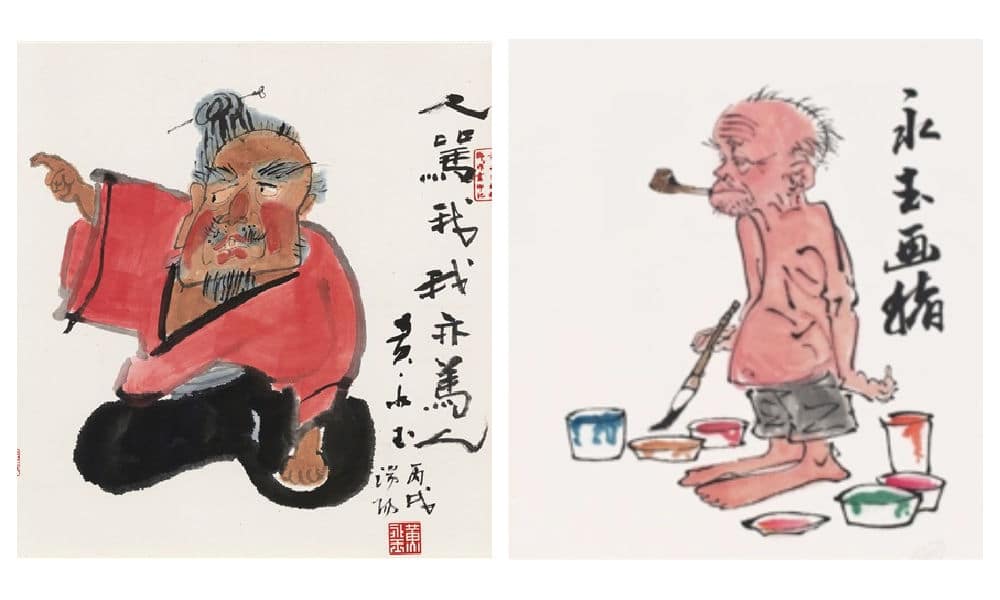

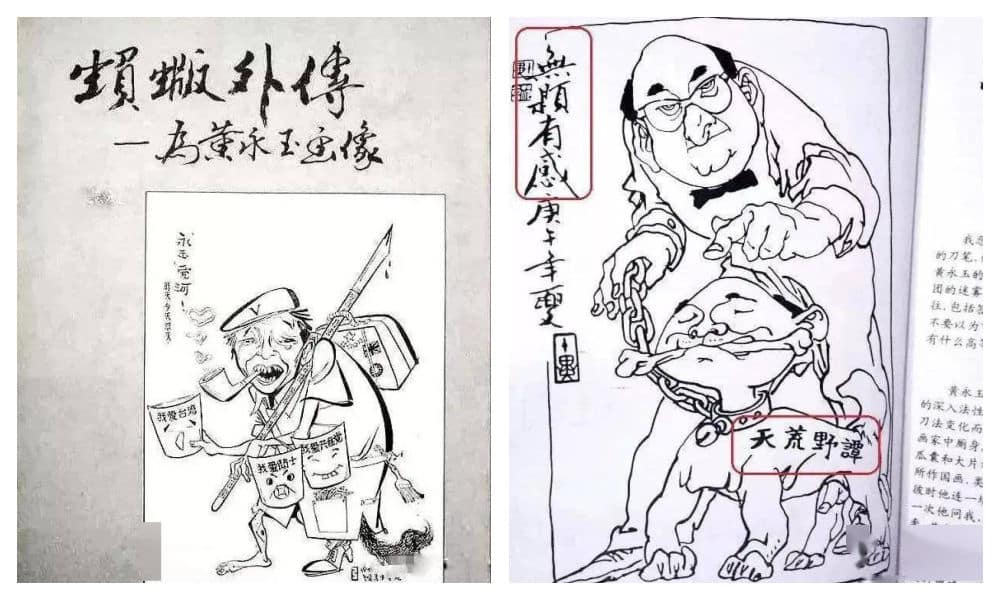

Another source of dislike stems from his history of disloyalty and his feud with another prominent Chinese painter, Huang Yongyu (黄永玉). Huang, who passed away in 2023, targeted Fan Zeng in some of his satirical paintings, including one titled “When Others Curse Me, I Also Curse Others” (“人骂我,我亦骂人”). He also painted a parrot, meant to mock Fan Zeng’s unoriginality.

Huang Yongyu made various works targeting Fan Zeng.

In retaliation, Fan produced his own works mocking Huang, sparking an infamous rivalry in the Chinese art world. The two allegedly almost had a physical fight when they ran into each other at the Beijing Hotel.

Fan Zeng mocked Huang Yongyu in some of his works.

Fan and Huang were once on good terms though, with Fan studying under Huang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Through Huang, Fan was introduced to the renowned Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文, 1902-1988), Huang’s first cousin and lifelong friend. As Shen guided Fan in his studies and connected him with influential figures in China’s cultural circles, their relationship flourished.

However, during the Cultural Revolution, when Shen was accused of being a ‘reactionary,’ Fan Zeng turned against him, even going as far as creating big-character posters to criticize his former mentor.[2] This betrayal not only severed the bond between Shen and Fan but also ended Fan’s friendship with Huang, and it is still remembered by people today.

Fan Zeng’s behavior towards another former mentor, the renowned painter Li Kuchan (李苦禪, 1899-1983), was also controversial. Once Fan gained fame, he made it clear that he no longer respected Li as his teacher. Li later referred to Fan as “a wolf in sheep’s clothes,” and apparently never forgave him. Although the exact details of their falling out remain unclear, some blame Fan for exploiting Li to further his own career.

There are also some online commenters who call Fan Zeng a “Mr Wang from next door” (隔壁老王), a term jokingly used to refer to the untrustworthy neighbor who sleeps with one’s wife. This is mostly because of the history of how Fan Zeng met his third wife.

Fan’s first wife was the Chinese female calligrapher Lin Xiu (林岫), who came from a wealthy family. During this marriage, Fan did not have to worry about money and focused on his artistic endeavours. The two had a son, but the marriage ended in divorce after a decade. Fan’s second wife was fellow painter Bian Biaohua (边宝华), with whom he had a daughter. It seems that Bian loved Fan much more than he loved her.

It is how he met his third wife that remains controversial to this day. Nan Li (楠莉), formerly named Zhang Guiyun (张桂云), was married to performer Xu Zunde (须遵德). Xu was a close friend of Fan, and helped him out when Fan was still poor and trying to get by while living in Beijing’s old city center.

Wanting to support Fan’s artistic talent, Xu let Fan Zeng stay over, supported him financially, and would invite him for meals. Little did he know that while Xu was away to work, Fan enjoyed much more than meals alone; Fan and Xu’s wife engaged in a secret decade-long affair.

When the affair was finally exposed, Xu Zunde divorced his wife. Still, they would use his house to meet and often locked him out. Three years later, Nan Li officially married Fan Zeng. Xu not only lost his wife and friend but also ended up finding his house emptied, his two sons now bearing Fan’s surname.

When Nan Li passed away in 2021, Fan Zeng published an obituary that garnered criticism. Some felt that the entire text was actually more about praising himself than focusing on the life and character of his late wife, with whom he had been married for forty years.

Fan Zeng and his four wives

An ‘old pervert’, a ‘traitor’, a ‘disgrace’—there are a lot of opinions circulating about Fan that have come up this week.

Despite the negativity, a handful of individuals maintain a positive outlook. A former colleague of Xu Meng writes: “If they genuinely like each other, age shouldn’t matter. Here’s to wishing them a joyful marriage.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Song, Yuwu. 2014. Biographical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China. United Kingdom: McFarland & Company, 76.

[2]Xu, Jilin. 2024. “Xu Jilin: Are Shen Congwen’s Tears Related to Fan Zeng?” 许纪霖:沈从文的泪与范曾有关系吗? The Paper, April 15. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_27011031. Accessed April 17, 2024.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?