China Arts & Entertainment

Why Disney’s Christopher Robin Is Not Released in China (And It’s Not Just Because of Winnie)

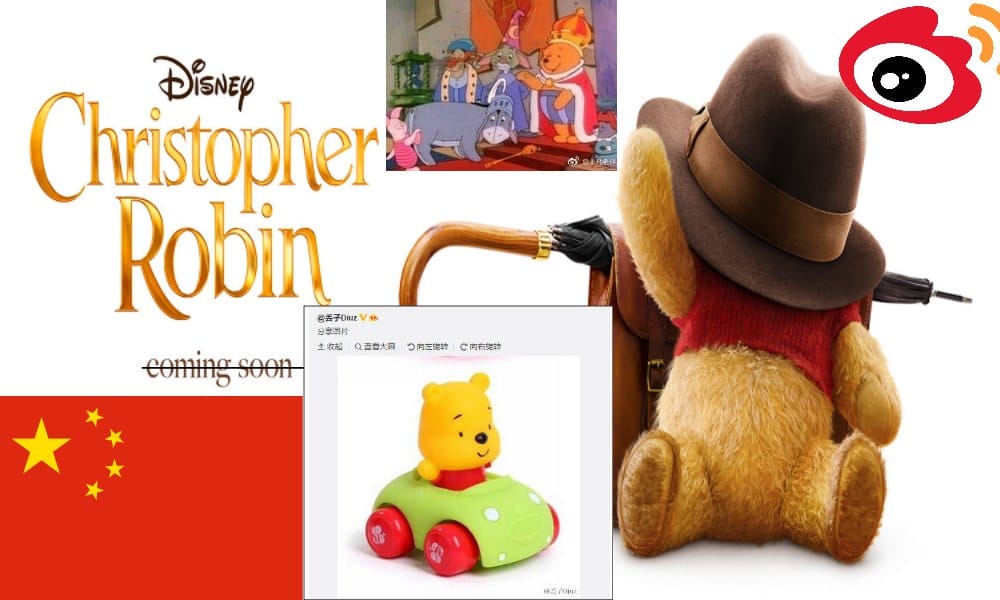

Recently, many foreign media reported that Disney’s ‘Christopher Robin’ (2018) will not be released in China due to an alleged “nationwide ban” on Winnie. But there is more to this than meets the eye.

Published

7 years agoon

Disney’s latest film Christopher Robin will not be released in Chinese cinemas. Many English-language media claim it is for the fact that the movie’s main star, Winnie the Pooh, is regarded too politically sensitive in the country. But these reports are clouded by misconceptions: Winnie is not banned in China, and it is common for Western films not to be released in the PRC. What’s on Weibo explains.

With contributions from Luka de Boni

“Christopher Robin, denied Chinese release, is the latest victim in China’s war on Winnie the Pooh,” writes Vox. “China gives Winnie the Pooh the enemy-of-the-state treatment,” says a recent New York Post headline.

Over the past days, the fact that Disney’s new 2018 film Christopher Robin will not premiere in mainland China has made headlines in many English-language media, first reported by The Hollywood Reporter.

Most sources allege that the movie, inspired by A. A. Milne and E. H. Shepard’s book Winnie-the-Pooh, will not be released in the country’s theatres because “Chinese leader Xi Jinping is prickly about comparisons between him and the lovable cartoon character, who has become a symbol of the resistance there” (Vox).

Film poster for Christopher Robin (Disney 2018).

BBC linked the film’s absence from Chinese movie theatres to Winnie and the supposed “nationwide clampdown on references to the beloved children’s character.”

But to what extent are these allegations true? There seem to be some misconceptions in many media about the scope of censorship on Winnie, and the release of non-Chinese films in mainland China.

What’s up with Winnie?

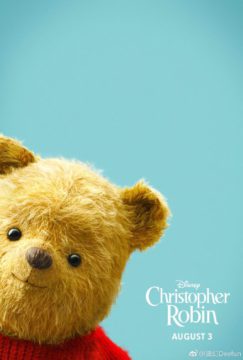

Over the past four years, Winnie the Pooh has, at times, been used as a political and satirical meme on Chinese social media, first becoming a target for China’s online censors when netizens compared Barack Obama and Xi Jinping, who met at the California Summit, with Pooh and Tigger in 2013.

In September of 2015, an image of Pooh became trending again on the day of the military parade. During the Beijing Parade that commemorated the 70th anniversary of WWII, President Xi Jinping drove around in a car (image), inspecting the troops.

When someone watching the parade then posted an image of Pooh bear in a toy car on Weibo, it was shared 62.000 times in little over an hour. Online responses included: “As I watched [the parade], I told my mother and father the similarities [between Pooh and the President] were uncanny.” The post was then soon deleted from Weibo.

This image of Pooh was censored in 2015.

The same happened in February of 2018, when images of Winnie the Pooh as a king emerged on Weibo after the end of China’s two-term limit on presidency was announced.

Could’ve expected this, but still pretty creative. First images of “king Winnie” surfacing on Weibo in response to Xi’s potential indefinite rule: https://t.co/u9kL5OYGwq #XiJinping #kingwinnie pic.twitter.com/Bb6Dmy46xH

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) 25 februari 2018

Although the censorship of Pooh at these specific moments are reason enough to call the bear some sort of “symbol of defiance against censorship,” it is not reason enough to assume the bear is at the epicenter of “a nationwide clampdown,” as BBC suggested.

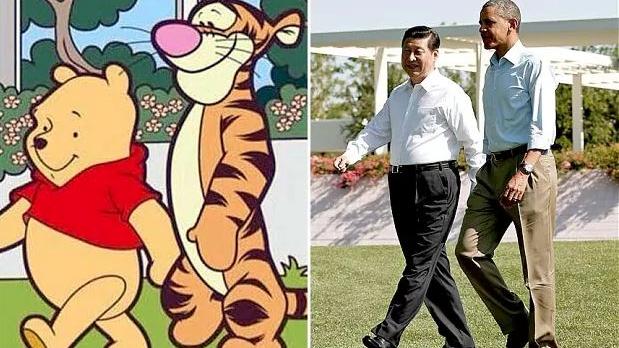

“Winnie the Pooh is not banned from China, neither online nor offline.”

Winnie the Pooh is not banned from China, neither online nor offline. The bear is quite popular, just as in many other countries, and people walk around wearing Pooh t-shirts and accessories in Chinese cities every day.

A current search on Chinese search engine Baidu for ‘Winnie the Pooh’ (“小熊维尼”) generates 8.5 million results. Taobao sells countless Winnie items on its e-commerce platform, and on social media site Weibo, thousands of Chinese netizens post photos of their Winnie-themed merchandise or favorite characters.

Random selection of Winnie-related posts on Weibo today (compilarion What’s on Weibo).

Disney’s Christopher Robin is also discussed online; not just by netizens but also by state media.

The moments that Pooh was censored on Chinese social media in the past, were times that China’s censorship machine was going at full-speed already. Any time that President Xi is taking part in an important meeting or event, whether it is a BRIC summit, military parade, or bilateral meeting, social media is more controlled than usual.

Because netizens were using the image of Pooh in a way that was meant to make fun of these high-profile political occasions and figures at particularly these times, they were censored. In other words: the Winnie images were censored along with many other things at particularly sensitive times for mocking a political event or figure.

Although it makes sense to say that Winnie the Pooh is perhaps more ‘sensitive’ than other cartoons (although Peppa Pig and Rage Comics had their share of censorship, too), it is questionable if this sensitivity is enough of a reason to ban Disney’s new blockbuster Christopher Robin.

Chinese Summer: Not a Time for Western Films

But if not for the bear itself, what would be a reason not to release a promising Disney movie? China’s strict foreign film import quota may play an important role.

Since the 1990s, China has a ‘foreign film quota.’ In the early years, this meant that just a small quote of foreign films were allowed to be imported into China, and in 2012, this was increased to 34 foreign movies per year. The amount of revenue that foreign producers can take from these movies is restricted to 25% (Latham 2007, 185; Ma 2017, 193).

Although Hollywood lobbyists have been negotiating with Chinese film authorities to allow more foreign films to be imported under revenue-sharing terms, there’s been little progress for now – the ongoing looming trade-war has not benefited the situation.

Besides the longstanding cap on foreign films, China also has unofficial ‘Hollywood black-out periods’ in which Hollywood blockbusters are prevented to enter the market so as to boost sales of local productions, a phenomenon dubbed “Domestic Film Protection Month” (国产电影保护月).

The term was allegedly coined in 2004, when Chinese media reported about an order restricting screening foreign films between June 10 and July 10 each year. Although the measure was never officially admitted by government officials, this unspoken policy has been executed for the past 14 years (read more here). As a consequence, it is common for big American productions to not be released in China during the summer months, the period where cinemas make the most revenues.

In 2011, for example, the Harry Potter blockbuster of the year was premiered in China five weeks later than it was in the rest of the world. Last summer, both Dunkirk and Spider-Man: Homecoming had their release dates delayed by several months, most probably to give the patriotic, local production Wolf-Warrior 2 a boost in sales.

These black-out periods can also serve another purpose. According to CNBC, they can also be used to give Chinese film authorities additional bargaining power in their negotiations with US lobbyists. With these negotiations increasing in importance lately, as a result of deteriorating US-China trade relations, it might make sense that Chinese authorities would want to put themselves in the most favorable bargaining position.

Each year, it is unclear when the ‘black-out period’ starts and ends. Generally, it can start as early as mid-June and finish as late as late-August.

Goodbye, Christopher Robin?

With many netizens and various state media (including China Global Television Network) posting about the release of Christopher Robin on Weibo and beyond, it is unlikely that political sensitivity over Winnie is the (only) reason why the film will not be shown in Chinese cinemas this summer.

Whether or not the film will definitely not come out in China is also not clear. The process of translation and censorship checking for films can take a long time and will sometimes mean films come out much later in the PRC.

Even when not reaching the big screens, most Hollywood blockbusters will eventually be available for viewing on online channels such as Youku or iQiyi.

Goodbye Christopher Robin (2017), another movie focusing on the story of Winnie the Pooh, is available for viewing on iQiyi and other (paid) streaming sites in China.

Many netizens would welcome a delayed release of Christopher Robin in China. The movie’s hashtag (#克里斯托弗·罗宾#) has already been viewed nearly three million times on Weibo.

While for many, the bear has no political connotations, there are also those who are still trying to post pictures of President Xi Jinping as Pooh – those will soon be deleted.

“I just wanted to see if it would be deleted,” the Weibo user says: “But actually, I really do think he’s cute.”

For more on this, check out today’s feature on BBC World Update (video by What’s on Weibo).

By Manya Koetse, and Luka de Boni

Follow @whatsonweibo

References

Latham, Kevin. 2007. Pop Culture China! Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. Oxford: ABC Clio.

Ma, Winston. 2017. China’s Mobile Economy: Opportunities in the Largest and Fastest Information Consumption Boom. Cornwall: Wiley.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

How K-pop Fans and the 13-Year-Old Daughter of Baidu VP Sparked a Debate on Online Privacy

What began as K-pop fan outrage targeting a snarky commenter quickly escalated into a Baidu-linked scandal and a broader conversation about data privacy on Chinese social media.

Published

1 month agoon

March 26, 2025By

Ruixin Zhang

For an ordinary person with just a few followers, a Weibo account can sometimes be like a refuge from real life—almost like a private space on a public platform—where, along with millions of others, they can express dissatisfaction about daily annoyances or vent frustration about personal life situations.

But over recent years, even the most ordinary social media users could become victims of “opening the box” (开盒 kāihé)—the Chinese internet term for doxxing, meaning the deliberate leaking of personal information to expose or harass someone online.

A K-pop Fan-Led Online Witch Hunt

On March 12, a Chinese social media account focusing on K-pop content, Yuanqi Taopu Xuanshou (@元气桃浦选手), posted about Jang Wonyoung, a popular member of the Korean girl group IVE. As the South Korean singer and model attended Paris Fashion Week and then flew back the same day, the account suggested she was on a “crazy schedule.”

In the comment section, one female Weibo user nicknamed “Charihe” replied:

💬 “It’s a 12-hour flight and it’s not like she’s flying the plane herself. Isn’t sleeping in business class considered resting? Who says she can’t rest? What are you actually talking about by calling this a ‘crazy schedule’..”

Although the comment may have come across as a bit snarky, it was generally lighthearted and harmless. Yet unexpectedly, it brought disaster upon her.

That very evening, the woman nicknamed Charihe was bombarded with direct messages filled with insults from fans of Jang Wonyoung and IVE.

Ironically, Charihe’s profile showed she was anything but a hater of the pop star—her Weibo page included multiple posts praising Wonyoung’s beauty and charm. But that context was ignored by overzealous fans, who combed through her social media accounts looking for other posts to criticize, framing her as a terrible person.

After discovering through Charihe’s account that she was pregnant, Jang Wonyoung’s fans escalated their attacks by targeting her unborn child with insults.

The harassment did not stop there. Around midnight, fans doxxed Charihe, exposing her personal information, workplace, and the contact details of her family and friends. Her friends were flooded with messages, and some were even targeted at their workplaces.

Then, they tracked down Charihe’s husband’s WeChat account, sent him screenshots of her posts, and encouraged him to “physically punish” her.

The extremity of the online harassment finally drew backlash from netizens, who expressed concern for this ordinary pregnant woman’s situation:

💬 “Her entire life was exposed to people she never wanted to know about.”

💬 “Suffering this kind of attack during pregnancy is truly an undeserved disaster.”

Despite condemnation of the hate, some extreme self-proclaimed “fans” remained relentless in the online witch hunt against Charihe.

Baidu Takes a Hit After VP’s 13-Year-Old Daughter Is Exposed

One female fan, nicknamed “YourEyes” (@你的眼眸是世界上最小的湖泊), soon started doxxing commenters who had defended her. The speed and efficiency of these attacks left many stunned at just how easy it apparently is to trace social media users and doxx them.

Digging into old Weibo posts from the “YourEyes” account, people found she had repeatedly doxxed people on social media since last year, using various alt accounts.

She had previously also shared information claiming to study in Canada and boasted about her father’s monthly salary of 220,000 RMB (approx. $30.3K), along with a photo of a confirmation document.

Piecing together the clues, online sleuths finally identified her as the daughter of Xie Guangjun (谢广军), Vice President of Baidu.

From an online hate campaign against an innocent, snarky commenter, the case then became a headline in Chinese state media, and even made international headlines, after it was confirmed that the user “YourEyes”—who had been so quick to dig up others’ personal details—was in fact the 13-year-old daughter of Xie Guangjun, vice president at one of China’s biggest tech giants.

On March 17, Xie Guangjun posted the following apology to his WeChat Moments:

💬 “Recently, my 13-year-old daughter got into an online dispute. Losing control of her emotions, she published other people’s private information from overseas social platforms onto her own account. This led to her own personal information also getting exposed, triggering widespread negative discussion.

As her father, I failed to detect the problem in time and failed to guide her in how to properly handle the situation. I did not teach her the importance of respecting and protecting the privacy of others and of herself, for which I feel deep regret.

In response to this incident, I have communicated with my daughter and sternly criticized her actions. I hereby sincerely apologize to all friends affected.

As a minor, my daughter’s emotional and cognitive maturity is still developing. In a moment of impulsiveness, she made a wrong decision that hurt others and, at the same time, found herself caught in a storm of controversy that has subjected her to pressure and distress far beyond her age.

Here, I respectfully ask everyone to stop spreading related content and to give her the opportunity to correct her mistakes and grow.

Once again, I extend my apologies, and I sincerely thank everyone for your understanding and kindness.”

The public response to Xie’s apology has been largely negative. Many criticized the fact that it was posted privately on WeChat Moments rather than shared on a public platform like Weibo. Some dismissed the statement as an attempt to pacify Baidu shareholders and colleagues rather than take real accountability.

Netizens also pointed out that the apology avoided addressing the core issue of doxxing. Concerns were raised about whether Xie’s position at Baidu—and potential access to sensitive information—may have helped his daughter acquire the data she used to doxx others.

Adding fuel to the speculation were past conversations allegedly involving one of @YourEyes’ alt accounts. In one exchange, when asked “Who are you doxxing next?” she replied, “My parents provided the info,” with a friend adding, “The Baidu database can doxx your entire family.”

Following an internal investigation, Baidu’s head of security, Chen Yang (陈洋), stated on the company’s internal forum that Xie Guangjun’s daughter did not obtain data from Baidu but from “overseas sources.”

However, this clarification did little to reassure the public—and Baidu’s reputation has taken a hit. The company has faced prior scandals, most notably a the 2016 controversy over profiting from misleading medical advertisements.

Online Vulnerability

Beyond Baidu’s involvement, the incident reignited wider concerns about online privacy in China. “Even if it didn’t come from Baidu,” one user wrote, “the fact that a 13-year-old can access such personal information about strangers is terrifying.”

Using the hashtag “Reporter buys own confidential data” (#记者买到了自己的秘密#), Chinese media outlet Southern Metropolis Daily (@南方都市报) recently reported that China’s gray market for personal data has grown significantly. For just 300 RMB ($41), their journalist was able to purchase their own household registration data.

Further investigation uncovered underground networks that claim to cooperate with police, offering a “70-30 profit split” on data transactions.

These illegal data practices are not just connected to doxxing but also to widespread online fraud.

In response, some netizens have begun sharing guides on how to protect oneself from doxxing. For example, they recommend people disable phone number search on apps like WeChat and Alipay, hide their real name in settings, and avoid adding strangers, especially if they are active in fan communities.

Amid the chaos, K-pop fan wars continue to rage online. But some voices—such as influencer Jingzai (@一个特别虚荣的人)—have pointed out that the real issue isn’t fandom, but the deeper problem of data security.

💬 “You should question Baidu, question the telecom giants, question the government, and only then, fight over which fan group started this.”

As for ‘Charihe,’ whose comment sparked it all—her account is now gone. Her username has become a hashtag. For some, it’s still a target for online abuse. For others, it is a reminder of just how vulnerable every user is in a world where digital privacy is far from guaranteed.

By Ruixin Zhang

Independently covering digital China for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

How Ne Zha 2’s Shen Gongbao Became Known as the Ultimate “Small-Town Swot”

Published

2 months agoon

March 1, 2025

PART OF THIS TEXT COMES FROM THE WEIBO WATCH PREMIUM NEWSLETTER

Over the past few weeks, the Chinese blockbuster Ne Zha 2 has been trending on Weibo every single day. The movie, loosely based on Chinese mythology and the Chinese canonical novel Investiture of the Gods (封神演义), has triggered all kinds of memes and discussions on Chinese social media (read more here and here).

One of the most beloved characters is the leopard demon Shen Gongbao (申公豹). While Shen Gongbao was a more typical villain in the first film, the narrative of Ne Zha 2 adds more nuance and complexity to his character. By exploring his struggles, the film makes him more relatable and sympathetic.

In the movie, Shen is portrayed as a sometimes sinister and tragic villain with humorous and likeable traits. He has a stutter, and a deep desire to earn recognition. Unlike many celestial figures in the film, Shen Gongbao was not born into privilege and never became immortal. As a demon who ascended to the divine court, he remains at the lower rungs of the hierarchy in Chinese mythology. He is a hardworking overachiever who perhaps turned into a villain due to being treated unfairly.

Many viewers resonate with him because, despite his diligence, he will never be like the gods and immortals around him. Many Chinese netizens suggest that Shen Gongbao represents the experience of many “small-town swots” (xiǎozhèn zuòtíjiā 小镇做题家) in China.

“Small-town swot” is a buzzword that has appeared on Chinese social media over the past few years. According to Baike, it first popped up on a Douban forum dedicated to discussing the struggles of students from China’s top universities. Although the term has been part of social media language since 2020, it has recently come back into the spotlight due to Shen Gongbao.

“Small-town swot” refers to students from rural areas and small towns in China who put in immense effort to secure a place at a top university and move to bigger cities. While they may excel academically, even ranking as top scorers, they often find they lack the same social advantages, connections, and networking opportunities as their urban peers.

The idea that they remain at a disadvantage despite working so hard leads to frustration and anxiety—it seems they will never truly escape their background. In a way, it reflects a deeper aspect of China’s rural-urban divide.

Some people on Weibo, like Chinese documentary director and blogger Bianren Guowei (@汴人郭威), try to translate Shen Gongbao’s legendary narrative to a modern Chinese immigrant situation, and imagine that in today’s China, he’d be the guy who trusts in his hard work and intelligence to get into a prestigious school, pass the TOEFL, obtain a green card, and then work in Silicon Valley or on Wall Street. Meanwhile, as a filial son and good brother, he’d save up his “celestial pills” (US dollars) to send home to his family.

Another popular blogger (@痴史) wrote:

“I just finished watching Ne Zha and my wife asked me, why do so many people sympathize with Shen Gongbao? I said, I’ll give you an example to make you understand. Shen Gongbao spent years painstakingly accumulating just six immortal pills (xiāndān 仙丹), while the celestial beings could have 9,000 in their hand just like that.

It’s like saving up money from scatch for years just to buy a gold bracelet, only to realize that the trash bins of the rich people are made of gold, and even the wires in their homes are made of gold. It’s like working tirelessly for years to save up 60,000 yuan ($8230), while someone else can effortlessly pull out 90 million ($12.3 million).In the Heavenly Palace, a single meal costs more than an ordinary person’s lifetime earnings.

Shen Gongbao seems to be his father’s pride, he’s a role model to his little brother, and he’s the hope of his entire village. Yet, despite all his diligence and effort, in the celestial realm, he’s nothing more than a marginal figure. Shen Gongbao is not a villain, he is just the epitome of all of us ordinary people. It is because he represents the state of most of us normal people, that he receives so much empathy.”

In the end, in the eyes of many, Shen Gongbao is the ultimate small-town swot. As a result, he has temporarily become China’s most beloved villain.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

China’s Major Food Delivery Showdown: What to Know about the JD.com vs. Meituan Clash

The Liaoyang Restaurant Fire That Killed 22 People

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

Aftermath of Suzhou Marathon’s “Pissing Gate”

Do You Know Who Li Gang Is? Anti-Corruption Official Arrested for Corruption

Beyond the Box Office: What’s Behind Ne Zha 2’s Success?

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Tuning Into the Year of the Snake

“Black Myth: Wukong”: From Gaming Screens to the CMG Spring Festival Gala?

Collective Grief Over “Big S”

US-Russia Rapprochement and “Saint Zelensky”: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Shake-Up

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

The ‘China-chic Girl’ Image and the Realities of China’s Competitive Food Delivery Market

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight12 months ago

China Insight12 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Digital11 months ago

China Digital11 months agoChina’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoSinging Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

-

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers12 months ago

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers12 months agoA Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea