Chinese Movies

A Film Lover’s Complaint: Netizens Weary of China’s “Domestic Movie Protection Month”

During the summer season, big international movies are blocked from Chinese cinemas. The policy, meant to boost China’s domestic film industry, is a dreaded one amongst China’s movie-loving social media users.

Published

7 years agoon

During China’s summer season, big international movies are blocked from cinemas in the PRC. The policy, meant to boost China’s domestic film industry, is a dreaded one amongst many movie-loving social media users.

This summer, while big Hollywood films such as Spiderman: Homecoming or War of the Planet of the Apes are riding the heat wave in North America, audiences in China will not be seeing them until end of August. The only big western film they can see during this two-month-period is Despicable Me 3.

The measure is a much-dreaded one on Chinese social media, where many young people complain that now that they finally have the time to go and see their favorite movies in the cinema, they can’t because they are blocked: “I’m always in school and can’t see any movies. Now that I’m free I still can’t see them.”

DOMESTIC FILM PROTECTION MONTH

“What once started out as a month-long Hollywood ‘blackout’ has gradually extended over the years.”

The reason behind the delay is the “invisible hand” of the Chinese state. During the summer holidays, the Chinese National Film Board blocks many imported foreign blockbusters, a phenomenon called “Domestic Film Protection Month” (国产电影保护月).

The term was allegedly coined in 2004, when Chinese media reported about an order restricting screening foreign films between June 10 and July 10 each year. According to Baidu Baike (百度百科), Baidu’s equivalent of Wikipedia, there are no publicly available official documents defining this policy.

The term was also used in an item published by regional media in 2006. The article (“国产电影保护月”沈阳遇冷引发议论“) states that the policy was launched in order to protect China’s domestic movie business. During “Domestic Film Protection Month,” as it was dubbed by the media and film industry, it is not “encouraged” to show big foreign films in China’s cinemas.

What once started out as a month-long Hollywood ‘blackout’ has gradually extended over the years. Currently, the blocking of foreign blockbusters lasts around 2 months each summer.

Although the measure was never officially admitted by government officials, this unspoken policy has been executed for the past 14 years. The policy has also extended to several other major national holidays like Chinese New Year and the National Day holiday. During these holidays, a majority of China’s population is off work – a peak moment for cinemas.

BOOSTING CHINA’S FILM INDUSTRY

“The scene in which Tom Cruise’s character kills two Chinese henchmen was one of those eliminated scenes, as it was deemed ‘truly insulting'”

There are various ways in which the Chinese state interferes in the movie industry to support and protect domestic film production. Besides the “Domestic Film Protection Month” and other measures – such as opening two big Hollywood movies on the same day – there is also a limit to the number of foreign films accepted into China’s cinemas; Chinese audiences can only see 34 overseas films per year. Revenues from these films are shared between the Chinese film distributors and the western producers.

The measurements are part of a wider campaign to boost the domestic film industry. In the 2005-2012 period, only one-third of China’s domestic movies were screened by China’s major cinemas; up to 80% of Chinese film projects lost money as a consequence. The ‘blackout’ periods need “to ensure that Hollywood films account for no more than 50% of the market in any given year” (Su 2016).

Some of the films that were postponed in China over the past decade include Spider-Man 2 (2004), Mr. Smith&Mrs Smith (2004) Garfield (2006), Transformers (2007), Harry Potter (2011), Ben-Hur (2016), and many others.

But support for domestic films is not always the only reason why the release of Hollywood films is postponed in Chinese cinemas. The process of translation and censorship also contributes to the final date a western film is released in China.

The release of Mission Impossible 3 in 2006, for example, was delayed because some scenes filmed in Shanghai needed to be erased. The scene in which Tom Cruise’s character kills two Chinese henchmen was one of those eliminated scenes, as it was deemed “truly insulting” by the China Film Group. The film could only be released after this part was censored.

FUTILE EFFORTS?

“Despite the endless efforts, Hollywood films are still making substantially more money than their domestic rivals in Chinese cinemas.”

Despite the endless efforts, Hollywood films are still making substantially more money than their domestic rivals in Chinese cinemas. In 2016, Terminator Genysis was the first big foreign film to come out after the ‘protection month.’

This film, that was rather mediocre considering its ratings and ticket sales in North America, received a warm welcome from Chinese audiences: it made a staggering RMB 181 million (USD 27million) on its opening day. Thanks to its sales in China, this film could be deemed – financially at least – a success.

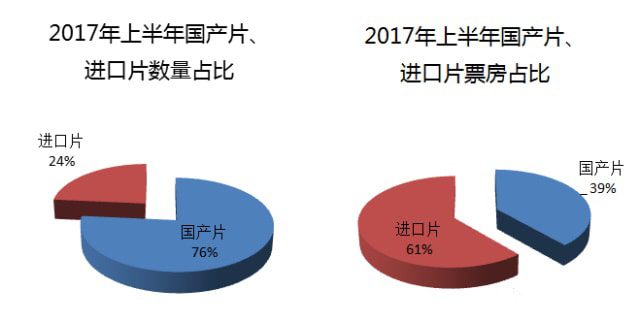

Data shows that in the first half of 2017, 76% of the published films were domestic ones – yet they only account for 39% of the total ticket sales.

Despicable Me 3, the only western film to have been allowed outside of this summer’s ‘Hollywood blackout’, exceeded RMB 300 million (USD 44.6m) in ticket sales within 2 days after its release. As of 31st July, 25 days after in Chinese cinemas, that number had already risen to RMB 990 million (±USD 147m).

Ironically, its success also comes as a result of the ‘Domestic Film Protection Month’. As some netizens say on Weibo: “Thanks to the domestic film protection month, ???, I’ve seen too many sh*t films; I need to see some cartoon [Despicable Me 3] to wash my eyes.”

A FILM-LOVER’S COMPLAINT

“I’m in despair – when will the ‘Domestic Film Protection Month’ finally be over?!”

On Chinese social media, many other film-loving netizens also complain about the summer restrictions on foreign movies and express their wish to watch big foreign films at the same time as the rest of the world. Many also indicate they would rather support movies based on their quality than where come from.

“I’m in despair – when will the ‘Domestic Film Protection Month’ finally be over?!” some commenters asked.

“Are you done protecting your stuff yet? I’m waiting,” others said.

Despite the criticism, there are also netizens who say they hope that China’s domestic cinema can grow and develop into a more thriving industry. Their wishes might be fulfilled, as recent reports show that Chinese films such as Wolf Warrior 2 (战狼2) are benefiting from the fact that China blocks international competition from the market during this period; the patriotic blockbuster made a massive $130M debut this summer.

Some netizens are satisfied despite the restrictions, and praised the movie on their Weibo account, adding: “Wolf Warrior 2 has become the movie hit of the summer. I didn’t expect it – it’s not easy to see a good movie during the ‘protect movies’ summer season.”

By Miranda Barnes & Richard Barnes

Follow @whatsonweibo

This article has been revised by the editor.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

References (online references linked to through text):

Su, Wendy. 2016. China’s Encounter with Global Hollywood. Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky.

Miranda Barnes is a Chinese blogger and part-time translator with a strong interest in Chinese media and culture. Born in Shenyang, she used to work and live in Beijing and is now based in London. On www.abearandapig.com she shares news of her travels around Europe and Asia with her husband.

China Arts & Entertainment

Top 9 Chinese Movies to Watch This Spring Festival Holiday

Lunar New Year lineup: These are the 9 Chinese films competing at the Spring Festival box office.

Published

6 months agoon

February 9, 2024

Over the past decade, China’s domestic film industry has experienced explosive growth, both in terms of production and box office revenue.

When it comes to the latter, the Spring Festival is the most important time of the year for box office success. Especially over the past few years, there has been more media focus on the Spring Festival season as the peak season for top domestic films.

During the Chinese Spring Festival, along with the National Day Holiday, movies tend to earn around 32.3% more on average. Sci-fi and action films are the most successful, followed by comedies (Li et al 2022, 128). Last year, the Spring Festival box office revenues accounted for about 12.3 percent of the yearly total.

Notable films in the Spring Festival lineup of 2023 included Zhang Yimou’s Full River Red (满红红), the sequal to China’s all-time highest-grossing sci-fi epic Wandering Earth (流浪地球2), espionage suspense movie Hidden Blade (无名), sports drama Ping Pong: The Triumph (中国乒乓之绝地反击), the comedy Five Hundred Miles (交换人生), animation feature Boonie Bears: Guardian Code (熊出没), and Tian Xiaopeng’s Deep Sea animation film.

Especially the first two movies, Full River Red and Wandering Earth 2, became box office hits, earning a respective RMB4.55 billion ($633 million) and RMB4.03 billion ($561 million).

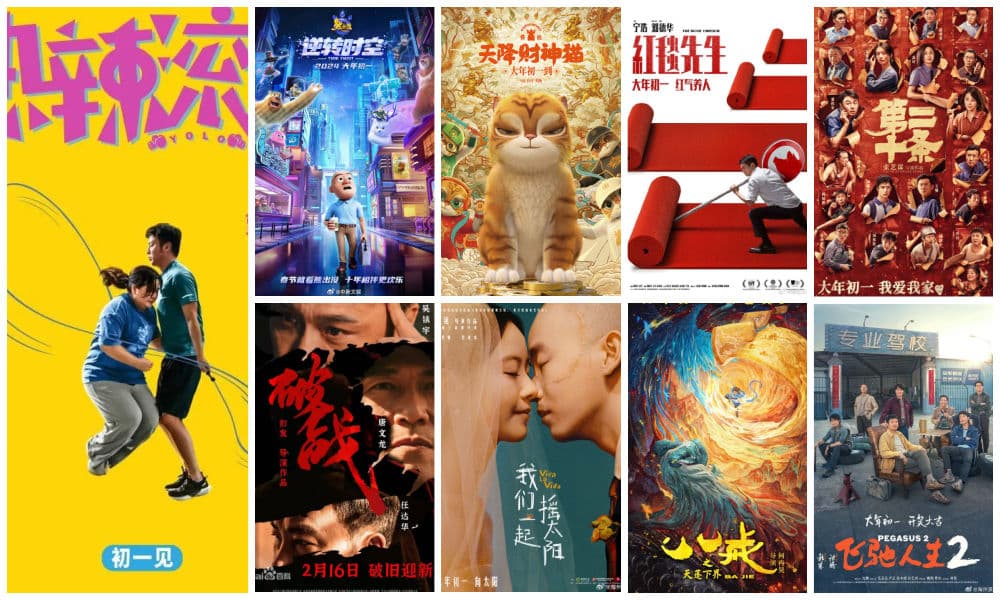

This year, there are nine big box office movies during the eight-day Chinese New Year’s holiday, and virtually all of them have recently also trended on Chinese social media. Here, we will list all nine of them and what you need to know about them.

1. YOLO 热辣滚烫

- Title: Chinese title: 热辣滚烫 Rèlà Gǔntàng, ‘Sizzling Hot‘; English title: YOLO

- Premiere: February 10, 2024

- Genre: Comedy/Sports Drama

- Runtime: 129 minutes

- Directed by: Jia Ling (贾玲), who previously also directed the 2021 Hi, Mom (你好,李焕英) movie.

- Screenplay by: Sun Jibin (孙集斌), who also did the screenplay for Hi, Mom. The film is based on the Japanese 2014 movie 100 Yen Love (百円の恋, Hyakuen no Koi).

- Starring: Jia Ling (贾玲), Jia Yinlei (雷佳音), Zhang Xiaofei (张小斐), Yang Zi (杨紫), Sha Yi (沙溢).

- About: YOLO (热辣滚烫), which will hit Chinese theaters on February 10, tells the story of Le Ying (乐莹), who has withdrawn from social life and isolated herself at home ever since graduation. Trying to get her life back on track, Le Ying meets a boxing coach. The meeting proves to be just the beginning of a new journey in life filled with unforeseen challenges.

- Trending: Chinese actress and director Jia Ling (贾玲) went trending on Weibo on the day she announced this upcoming movie because of her remarkable weight loss transformation; she lost a staggering 100 pounds (50 kg) for her role in this film.

2. Pegasus 2 飞驰人生2

- Title: Chinese title: 飞驰人生2 Fēichí Rénshēng 2, ‘High-speed Life 2‘; English title: Pegasus 2

- Premiere: February 10, 2024

- Genre: Comedy/Sports Drama

- Runtime: 121 minutes

- Directed by: Han Han (韩寒)

- Screenplay by: Han Han (韩寒).

- Starring: Shen Teng (沈腾), Fan Chengcheng (范丞丞), Yin Zheng (尹正), Zhang Benyu (张本煜), Sun Yizhou (孙艺洲).

- About: This is the sequal to Pegasus (2019), the 2019 Spring Festival blockbuster about passionate rally driver Zhang Chi (张驰, played by Shen Tang), who had to step away from racing due to a ban for illegal street racing. But he never gave up on his dream. Now, he’s gearing up for a major comeback, facing new competition. Based on the experiences of Han Han, a talented writer and professional rally driver, and his admiration for racer Xu Lang, Pegasus 2 continues this tale of determination and passion. Zhang Chi, now a driving school instructor, gets a chance to return to the track when offered sponsorship from a car factory to compete in a high-profile racing rally with a team he must assemble.

- Trending: Pegasus 2 is a much-anticipated movie among Chinese netizens, mainly because of the all-star cast including celebrated actor Shen Teng and young idol Fan Chengcheng. The movie’s January 29 promo event in Beijing also went trending when Fan Chengcheng posted a photo together with the cast members. This post was shared over a million times, receiving more than 100,000 comments.

3. Article 20 第二十条

Image via Weibo.

- Title: Chinese title: 第二十条 Dì èrshí tiáo; English title: Article 20

- Premiere: February 10, 2024

- Genre: Comedy/Family Drama

- Runtime: 141 minutes

- Directed by: Zhang Yimou (张艺谋)

- Screenplay by: Li Meng (李萌).

- Starring: Lei Jiayin (雷佳音), Ma Li (马丽), Zhao Liying (赵丽颖), Gao Ye (高叶), Liu Yaowen (刘耀文)

- About: Zhang Yimou’s Article 20 tells the story of prosecutor Han Ming (韩明, Lei Jiayin) who is facing a particularly difficult legal case at work, while navigating complicated situations at home, especially after his son got into a fight with the son of the school leader. As Han Ming strives to balance work and family responsibilities, he courageously fights for fairness and justice in his own way.

- Trending: As one of China’s most prolific film directors, Zhang Yimou’s work always gets a lot of attention on Chinese social media. This time, some of the Weibo hashtags related to this movie received millions or even billions of views. Especially the young celebrity and teen idol Liu Yaowen (2005) is receiving attention for starring in this film as Han Ming’s son Han Yuchen who beats up the school director’s son and then refuses to apologise. Some online polls asking netizens which movie they’re most excited to see this Spring Festival (投票:你春节打算看哪部电影) also indicate that Article 20 is one of the most anticipated movies on this list.

4. The Movie Emperor 红毯先生

Image via Kwongwah.

- Title: Chinese title: 红毯先生 Hóngtǎn Xiānshēng, ‘Mr. Red Carpet’; English title: The Movie Emperor

- Premiere: February 10, 2024

- Genre: Comedy/Drama

- Runtime: 127 minutes

- Directed by: Zhu Hao (宁浩)

- Screenplay by: Liu Xiaodan (刘晓丹), Wang Ang (王昂)

- Starring: Andy Lau (刘德华), Pal Sinn Lap-man (单立文), Rima Zeidan (瑞玛·席丹), Yu Weiguo (余伟国), and Ning Hao (宁浩).

- About: Andy Lau plays the main character in this film, a renowned Hong Kong film star who is preparing for a major comeback in a rural-themed film. To prepare for his role as a peasant farmer in the 1960s, he immerses himself in rural life in China, which leads to all kinds of bizarre situations that satirically reflect on the present-day entertainment industry.

- Trending: The Movie Emperor is perhaps among the more serious comedies in this list, as it has a deeper message about the dynamics of the entertainment industry and present-day society. With a career spanning over four decades, there’s perhaps no other actor who’d be more suited to play this character than Andy Lau, and many commenters are looking forward to see him in this role.

5. Viva La Vida 我们一起摇太阳

Image via Yule 360.

- Title: Chinese title: 我们一起摇太阳 Wǒmen Yìqǐ Yáo Tàiyáng, ‘Shake the Sun Together’; English title: Viva La Vida

- Premiere: February 10, 2024

- Genre: Romantic comedy-drama

- Runtime: 129 minutes

- Directed by: Han Yan (韩延)

- Screenplay by: Han Yan (韩延), Li Liangwen (李亮文), Wang Xiaoyi (王小艾), Yang Fuzhi (杨富芝)

- Starring: Peng Yuchang (彭昱畅), Li Gengxi aka Teresa Li (李庚希), Xu Fan (徐帆), Gao Yalin (高亚麟), Liu Dan (刘丹).

- About: This movie is the third and final movie in the director Han Yan’s “Life Trilogy” of of uplifting films centered around the theme of battling cancer. It follows the successes of the previous hits, Go Away Mr. Tumor and A Little Red Flower, released in 2015 and 2020 respectively. The narrative focuses on the romance between a girl suffering from kidney dysfunction (Teresa Li) and a boy afflicted with a brain tumor (Peng Yuchang). Despite their contrasting personalities, they find unity in their shared struggles with illness, embarking on a journey that celebrates the essence of life.

- Trending: These days, movie production teams are doing all they can to go trending on social media to increase the hype surrounding their films. In light of their promotional activities, actor Peng Yuchang went to Tianjin to join the ‘diving grandpa’s’ (#彭昱畅和天津大爷一块跳水#). This is a group of elderly swimmers who went viral in 2023 because of their daring dives into the river from the Stone Lion Forest Bridge (狮子林桥). People joked about Peng swimming in the cold river, saying they had “never seen a male lead work so hard to promote their film.”

6. Boonie Bears: Time Twist 熊出没:逆转时空

Image via Moonlight Media

- Title: Chinese title: 熊出没:逆转时空 Xióng Chūmò: Nìzhǔan Shíkōng; English title: Boonie Bears: Time Twist

- Premiere: February 10, 2024

- Genre: Comedy sci-fi animation

- Runtime: 108 minutes

- Directed by: Lin Huida (林汇达)

- Screenplay by: Xu Yun (徐芸), Wan Qin (万秦), Jiang Lin (蒋琳)

- Starring: Tan Xiao (谭笑), Zhang Bingjun (张秉君), Zhang Wei (张伟), Zhang Ming (张茗)

- About: This latest film from the Boonie Bears universe revolves around the stressed-out white-collar worker Vick (光头强), who has left his small town and forest job for a career in the big city. However, his absence has some far-reaching consequences. When he accompanies his boss on a work trip, he embarks on an adventure through time and space, that’s all about exploring life goals and finding self-fulfillment.

- Trending: While this film may not be among the top trending movies this Spring Festival season, it’s still a beloved choice for both Boonie Bears fans and parents who want to take their kids to the movies this holiday. This is also a special Boonie Bears year, as it marks both the 12th anniversary of the Chinese “Boonie Bears” cartoon franchise and the 10th anniversary of the first feature film, “Boonie Bears: To the Rescue” (熊出没之夺宝熊兵).

7. Ba Jie 八戒之天蓬下界

Image via Xigua.

- Title: Chinese title: 八戒之天蓬下界 Bājiè zhī Tiānpéng Xiàjiè; English title: Article 20

- Premiere: February 10, 2024

- Genre: Animated fantasy adventure

- Runtime: 88 minutes

- Directed by: He Ranhao (何冉昊)

- Screenplay by: Li Meng (李萌).

- Starring: Zhang Lei (张磊), Ji Guanlin (季冠霖), Zhao Mingzhou (赵明洲), Gao Zengzhi (高增志), Ma Dehua (马德华)

- About: This is the first animated film in China about Ba Jie, a renowned character from the 16th-century novel Journey to the West (西游记) who is known for being part human and part pig – as well as being lazy and gluttonous. Presented as a quintessentially Chinese animation film, Ba Jie is not just a contemporary adaptation of a Chinese classic, it also embraces a style and color palette that builds on Chinese tradition. Originally announced for release in 2021 for 2022, coinciding with the Year of the Pig, the movie was then rescheduled for 2023, and now is finally making its premiere in the Year of the Dragon. Ma Dehua (马德华), who played Ba Jie in the famous 1986 “Journey to the West” TV series is also a voice actor in this film.

- Trending: The fact that this film was delayed and is already three years old by the time it hits cinemas does not exactly add to its appeal. Many people feel like they’ve seen the film posters again and again, and that its momentum has already passed.

8. Broken Mission 破战

Image via QQ.

- Title: Chinese title: 破战 Pò Zhàn, ‘Break War’; English title: Broken Mission

- Premiere: February 16, 2024

- Genre: Drama / Action / Suspense

- Runtime: 86 minutes

- Directed by: Peng Fa aka Danny Pang (彭发)

- Screenplay by: Peng Fa (彭发)

- Starring: Wu Zhenyu (吴镇宇), Simon Yam (任达华), Cheng Yuanyuan (程媛媛), Tang Wenlong (唐文龙), Liu Yingyi (刘颖仪).

- About: Although this movie won’t hit cinemas until February 16, it’s still considered a Spring Festival movie. Set in Hong Kong, this action-packed film revolves around the confrontation between the local police team and a criminal committing crimes in service to his “Savior.” The filming already started in 2019, and because of the big delay – partly due to many revisions in the script – the movie seems to have lost some of its relevance.

- Trending: Together with Ba Jie, Broken Mission is among the least popular movies in this list. There have also been very few promotional activities surrounding the premiere. In an online poll asking netizens which movies they anticipated most, these two received the least votes. YOLO and Article 20 received the most votes. Given its lack of popularity, some netizens propose that the movie should bypass cinemas entirely and go directly to online streaming services instead.

9. Huang Pi: God of Wealth Cat 黄貔:天降财神猫

Image via Weibo.

- Title: Chinese title: 黄貔:天降财神猫 Huáng Pí: Tiānjiàng cáishén māo; English title: Huang Pi / God of Wealth Cat or God of Money

- Premiere: February 10, 2024

- Genre: Animation/Comedy

- Runtime: 82 minutes

- Directed by: Bai Ding (白丁) and Guan Yang (关杨)

- Starring: Li Meng (李盟), Yan Nan (闫楠), Wang Zi (王梓), Yang Tianxiang (杨天翔), Liu Yike (刘依可).

- About: Inspired by Monkey King Wreaks Havoc in Heaven, this Mandarin-Cantonese bilingual animated movie revolves around Huang Pi, who is transformed into a cat by the Four Heavenly Kings after causing trouble in the Heavenly Palace. In order to repay the kindness of the God of wealth who rescues him, Huang Pi descents to the mortal world with his five incarnations. Here, he faces various challenges, one of which involves being mistaken for a stray cat by a pet hospital owner.

- Trending: The ‘lucky cat’ theme and Chinese artistic influences makes this movie a suitable one for the Spring Festival, with many people and animation fans anticipating its premiere.

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References

Li, Xuefei, Hua Lu, Chengzhong Wu. 2022. “The Destiny of Movies’ Box Office Performance in China: An Expectation–Evaluation Model.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 52(2): 117-135.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

Jia Ling Returns to the Limelight with New “YOLO” Movie and 110-Pound Weight Loss Announcement

After a year away from the spotlight, Chinese actress and director Jia Ling is back, announcing both a new film and slimmer figure.

Published

7 months agoon

January 11, 2024

Chinese actress and director Jia Ling (贾玲) has been trending on Weibo thanks to her upcoming film YOLO (热辣滚烫) and her remarkable weight loss transformation.

Jia Ling is a famous Chinese comedian actress, known for her annual Spring Festival Gala performances. She has been especially successful in the previous years as she made her directorial debut in 2021 with the award-winning box office hit Hi, Mom (Chinese title Hi, Li Huanying 你好,李焕英), in which she also stars as the female protagonist. That same year, audiences saw her as Wu Ge in Embrace Again (穿过寒冬拥抱你).

It has been a while since we’ve heard from Jia Ling, but on January 11, she resurfaced with a Weibo post in which she explained her absence from the limelight.

In her post, Jia wrote that she has spent the entire year working on the YOLO (热辣滚烫) movie, for which she lost a staggering 100 jin (斤) (110 lbs/50 kg). Just as with Hi, Mum, Jia is both the director of YOLO and the lead actress.

According to Jia, it was a tiring and “hungry” year, during which she ended up “looking like a boxer.” She added that the movie, set to premiere during the Spring Festival, is not necessarily about weight loss at all, but about learning to love yourself.

Within a single day, Jia Ling’s post received nearly 60,000 replies and over 855,000 likes.

Jia Ling’s post on Weibo.

The topic became top trending due to various reasons. It is because fans are excited to see Jia Ling back in the limelight and are anticipating the upcoming movie, but also because they are eager to see Jia Ling’s transformation.

From fans on Weibo: Jia Ling fanart and a meme from one of her well-known Spring Festival performances.

A short scene from the movie showed Jia Ling’s slimmer appearance, and a screenshot of it went viral, with Weibo users saying they hardly recognized Jia anymore.

One hashtag related to Jia Ling’s weight loss, about expert views on losing so much weight in such a relatively short time, received over 450 million on Weibo on Thursday (#医生谈贾玲整容式暴瘦#).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, medical experts quoted by Chinese media outlets caution against rapid weight loss methods, recommending a more gradual approach instead.

Nevertheless, there is great interest in the extreme diets of Chinese celebrities. As discussed in an earlier article about China’s celebrity weight craze, the weight loss journey of Chines actors or influencers often capture widespread attention as people are keen to adopt diet plans promoted by celebrities.

YOLO (热辣滚烫), which will hit Chinese theaters on February 10, tells the story of Le Ying (乐莹), who has withdrawn from social life and isolated herself at home ever since graduation. Trying to get her life back on track, Le Ying meets a boxing coach. The meeting proves to be just the beginning of a new journey in life filled with unforeseen challenges.

The Spring Festival holiday typically sees peak box office numbers in China, making this movie highly anticipated, particularly after the success of Hi, Mum three years ago. On Weibo, many view Jia Ling’s weight loss as a testament to her dedication and are eager to see the results of her year-long efforts in the cinema next month.

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Roge Arias

August 5, 2017 at 1:54 am

I have seen some of that too; didnt know it was real , tho … i mean, the phone is that strong – must be at least a little – exagerated: but i have read about the agm x2 tho: i dunno about durabilty yet but the specs are reeeeally good!the Qualcomm Snapdragon 800 alone is quite interesting in that price range

Luis Tejada

August 5, 2017 at 2:30 am

The ruggeds usually ARE more expensive but , dude: they are too good i mean: why should i get a phone that is gonna break for a ridiculous fall if i can have something like the X1 or x2 ( talking about AGM) for waaay less than a sansumg… not even nomu; their phones are not like they look in their annoucements and their Customer services is awful; i honestly prefer Agm most that all for the good english customer service and the specs too.

Luis Tejada

August 5, 2017 at 2:30 am

I love WJLF in this one! He is my fav! By the way, i have seen him promoting this brand before ( Agm phones) , a friend of mine have one and it looks amazing but i am too embarassed to ask him to let me toss his phone like in the movie xD