China Society

Beijing Introduces New Rules: Employers Can No Longer Ask Female Candidates about Marital or Childbearing Status

It’s supposed to promote equality on the job market, but will it change things?

Published

6 years agoon

First published

Chinese employers are reportedly no longer allowed to ask female job candidates if they are married or have children. But will this help the position of Chinese women on the job market?

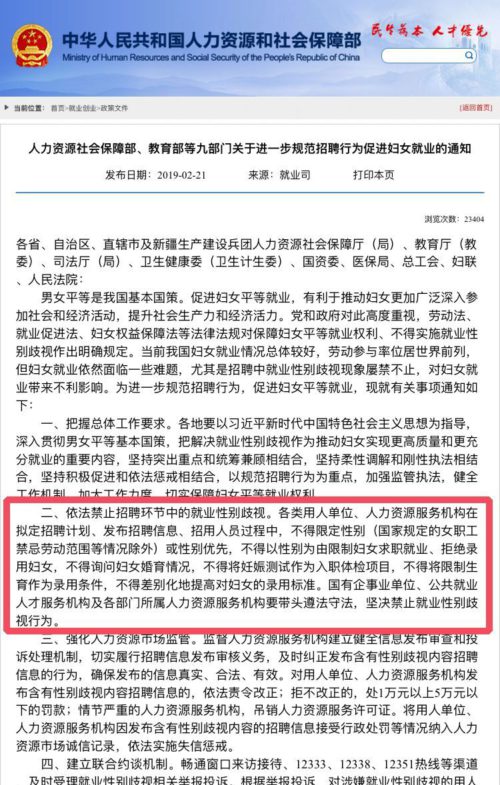

Nine government departments in Beijing have jointly released a document stating that employers are no longer allowed to ask female job candidates about their marital or childbearing status.

Although the issue made headlines in China on June 27, a document issued by the Chinese Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security in February of this year already contained the stipulations. The notice shared by state media today is dated May 20, 2019.

The document is titled “Notice on Further Strengthening Recruitment Management to Promote Women’s Employment” (“关于进一步加强招聘活动管理促进妇女就业工作的通知”) (link), and states that no requirements for gender should be included in any recruitment plans or interviews.

Xinhua News reports that the document prohibits asking about the marital or fertility status of female candidates during interviews, and also eliminates pregnancy testing from pre-employment health examination lists.

The recent move is part of a wider effort led by China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security to ban discrimination against women in the workforce.

Companies violating these rules will reportedly be fined 10,000 yuan ($1452) or more if they refuse to correct their practices.

At time of writing, the topic “Recruiters Cannot Ask about Women’s Marital & Childbearing Status” (#招聘不得询问妇女婚育情况#) received over 340 million views on social media platform Weibo.

Gender discrimination on China’s job market

Gender discrimination in the job-search process has been a hot topic in China for years. A 2015 study found that 87% of female college grads say there is gender discrimination for female job candidates.

The position of women in China’s job market is a complicated one.

On the one hand, education levels for women have greatly improved among Chinese women over recent decades, bringing greater gender equality – not just within the family, but within the society at large.

China boasts one of the higher levels of female labor force participation in the world. In 2018, the female labor force participate rate was 61%.

But at the same time, Chinese women face huge disadvantages in their working lives. Preferences for male candidates are ubiquitous in job advertisements, or may state that women who are married with children are preferred candidates. On average, women also still earn 36% less than men for doing similar work.

Since the end of the One Child Policy, social pressure to have a second child and calls for extended maternity leaves for women are potentially harming the (economic) position of women in China in the long run.

With a 98-day paid maternity leave and paid leave for prenatal checkups, Chinese laws on maternity leave are quite generous. But because this significantly increases the financial costs for (private) companies, many employers would rather hire a man than a woman who has not had children yet.

With the introduction of the “two-child-policy”, a woman could take a total paid leave of almost 200 days if she had two children. Calls to extend maternity leave to three years caused controversy on Weibo in 2014, when women said that nobody would hire a woman that could potentially be gone for six years.

In 2018, news came out that one school in Zhengzhou, Henan, had a policy of giving ‘time slots’ to female teachers to get pregnant with their (second) child. When one female teacher fell pregnant before her ‘turn’ was up, she was dismissed.

Earlier this year, the case of a woman in Dalian who was let go by the company for falling pregnant within her trial period also ignited discussions online.

When women who are already employed have a baby, they also have a greater chance of being demoted or earning less. A survey by job recruitment site Zhaopin.com found that 33 percent of women had their pay cut after giving birth and 36 percent were demoted (NPR).

When it was announced in 2016 that Anhui province would introduce a paid ‘menstrual leave’ for working women on their period, many female netizens protested the policy, saying that granting women special days off would only “make it even harder for women to be hired.”

Will this really help?

As for the latest announced regulations – many netizens are not too optimistic that they will actually change the position of women on the job market.

“Lazy politics, do they think that a few laws will solve the basic problem? And that companies will listen?”

“How will you implement these regulations?”, others wonder.

“Even if they’re not allowed to ask, they have others way to find out your status,” another person writes.

One Weibo commenter remarks: “I asked my friend who works in human resources if they really ask these questions. He answered: ‘Of course we don’t, that would be very unprofessional.’ ‘But if you filter out the resumes do you take gender into account?’ He answered: ‘Ha ha ha! Of course we do!'”

Some responses on Weibo are even more pessimistic, saying: “This will just make companies deny women of a certain age altogether. If you really want to change things you should give both men and women maternity leave.”

“To be honest,” one commenter named Absolom writes: “The costs that come with women’s childbearing should either be a responsibility taken up by the family (if you think that childbearing is a private affair), or by the state (if you think heightening childbearing rates is of importance to society). The ones least responsible for this are companies. If you put all responsibility on companies, I’m afraid that it’s still the women who suffer in the end. If they’re not allowed to ask, these companies simply won’t hire women of childbearing age at all.”

The majority of comments on Weibo also convey the idea that the policy might lead to companies not hiring women at all anymore; making things worse for them instead of improving their position on the job market.

But not all responses are negative. “I do support this policy,” one person comments: “When I just graduated and was looking for a job, one employer once expressed his concern over my single status, [saying] they were afraid I’d get married. Recently I was also looking for work, and one person straightforwardly asked me if I was okay with quitting my job if I’d get pregnant.”

Even so, the supportive comments are difficult to find among the thousands of reactions. “Are you 30 and single?” one Weibo user writes: “You might as not go to the job interview at all anymore.”

By Manya Koetse, with contributions from Miranda Barnes

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

You may like

China Society

Online Debates About China’s Train Traditions: No More Instant Noodles or Cigarette Breaks?

There’s talk of a ‘de-instant-noodling’ of China’s high-speed trains, but many netizens think smoking on the platform is the stinkier problem.

Published

4 days agoon

August 23, 2025

For many Chinese train travelers, especially those going long distances and spending entire days or nights on the train, an easy instant noodle (pào miàn 泡面) meal and a quick cigarette break on the platform during a short stop are standard — even indispensable — parts of the journey.

But some changes may be on the horizon. Over the past few days, heated discussions on Chinese social media have focused on the future of these train “traditions.”

Instant noodles on long-distance trains have been a common way to eat since the early 1990s. Trains usually provide free boiling water to cook the noodles, making them a convenient way to have a hot meal for lunch or dinner — and much cheaper than the boxed rice meals offered on board.

Image via @人民网评.

This month, Guangzhou East Railway Station, along with Baiyun Railway Station, suddenly stopped selling instant noodles in station shops. The change, implemented in August, triggered the so-called “Railway Instant Noodles Debate” (高铁泡面话题).

According to reports, the decision is tied to nationwide railway efforts to “maintain cleanliness” in stations and on trains, and to provide passengers with “higher-quality service.”

Further adding to the unrest is the fact that the China Railway travel guide also advices passengers to avoid eating strongly odorous foods such as “durian, instant noodles” during their travels. Whereas regular instant noodles can be brought on board, they’re officially not recommended to eat. Durian and stinky tofu are not allowed, along with self-heating hotpots, which can trigger smoke alarms.

The phrase “High-speed railways are de-instant-noodling” (#高铁去泡面化#) trended on Weibo.

Although official railway customer service stated they have not received any notice about an official, nationwide ban on instant noodle sales in high-speed rail stations, the topic still generated major discussion.

At the core of the debate is this contradiction: everyone enjoys eating their own noodles on the train, but many people hate the smell of other people’s noodles. Beyond the strong smell, people walking through the carriage with their hot noodles also pose a safety hazard (not to mention the mess when someone accidentally drops their cup noodles).

Smoking on Train Platforms: The Stinkier Problem?

The noodle debate soon expanded into another topic: smoking on train platforms. Many netizens argue that smoking on platforms is a far more pressing issue than passengers eating noodles (#高铁站台禁烟比禁止吃泡面更紧迫#), as cigarette smoking before/during travel on the outside train platforms causes a real nuisance for people who just want some fresh air.

It’s clearly a hot topic these days, with various related hashtags going trending. One media post about banning smoking on platforms vs. banning noodles on trains received nearly 80,000 likes and thousands of comments.

In China, it’s very common for passengers to take a quick cigarette break on the platform before the train continues.

In the past, people smoked on the trains themselves, especially in the areas between carriages. Since 2014, however, smoking has been banned on all high-speed and regular trains.

Since 2022, the ban has extended to all other passenger trains, waiting halls, and indoor areas of railway stations.

Outdoor platforms remain the last tolerated place to smoke before a long journey or during a short stop.

But for many non-smokers, this practice is bothersome, as the lingering smell leaves them no smoke-free area to wait for boarding.

Lately, anti-smoking influencers have gained traction in China, posting videos of themselves confronting smokers in public. Applauded by some and criticized by others, this trend has further fueled the platform-smoking debate.

As part of this anti-smoking movement, more people are calling out the lack of enforcement of smoking bans in public areas.

Still, opinions remain divided. Many netizens dislike smoke on train platforms, but argue it would be difficult to enforce a ban outdoors. If platforms are banned, they say, then pedestrian streets, shopping districts, and other outdoor public spaces should be too.

In the end, though opinions vary, most people agree on one thing: the smell of noodles on a train can sometimes be unpleasant, but it’s nothing compared to the smell of cigarette smoke. For now, the majority of Chinese netizens seem to favor a smoking ban on train platforms over a “de-noodling” of the trains.

“The only thing I dislike about the smell of noodles is that it makes me regret not buying some myself,” one commenter wrote.

Another worried Xiaohongshu user wrote: “A train ride without the noodles is only half as fun!”

For now, passengers don’t need to worry about losing their much-beloved train noodles just yet. Whether or not station shops sell instant noodles, travelers can still bring their own as long as official regulations still allow it (and they do).

If you really want to play it safe: bring your own noodles but eat them in the train’s dining carriage, which also allows people to eat self-brought food.

And for those who want a quick smoke on the platform—it’s also still possible, though perhaps not for long.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Society

The Rising Online Movement for Smoke-Free Public Spaces in China

From foreign anti-smoking bloggers to the “Modern Lin Zexu,” China is seeing a rise in online anti-smoking activism.

Published

2 weeks agoon

August 14, 2025

Anti-smoking activism, especially by foreigners, has recently drawn attention on Chinese social media. A renewed online push to stop smoking in no-smoking areas highlights broader challenges of enforcing public smoking bans in a country where smoking remains prevalent.

From “smoking is prohibited in public spaces” (#公共场所禁止吸烟#) to “tobacco control” (#控烟#), anti-smoking hashtags have been popping up more frequently on Chinese social media. Many of them accompany videos from influencers who call out or try to stop people smoking where it’s not allowed.

Some of these influencers aren’t even Chinese.

In recent years, Chinese media reports and online discussions have fueled a perception among many netizens that foreigners in China often receive preferential treatment. In certain situations, this perception seems to hold true — perhaps linked to a belief among some officials that incidents involving foreigners are diplomatically sensitive and tied to China’s image. This can lead to extra caution or leniency in handling such cases, sometimes giving foreigners an unspoken advantage in public-facing services and spaces, from dormitories to restaurants.

Now, some netizens are suggesting that foreign residents use this “advantage” to report public smoking violations more actively.

A post on RedNote saying, “I hope every foreigner traveling to China will help complain about the problem of smoking in public spaces in China,” received many likes and thousands of comments.

Others even suggest that foreigners could quickly build their social media followings by posting such encounters, dubbing them “anti-smoking bloggers” or “smoking-dissuasion bloggers” (劝烟博主).

Foreign Influencers’ Anti-Smoking Efforts Go Viral

One of these anti-smoking foreign bloggers is Xiaohongshu blogger “Alibabame” (alibabame 艾伦, real name Malik X.). On July 30, he posted a video in which he asked two Chinese men to stop smoking in a restaurant with a prominent “No Smoking” sign, speaking mostly in English with some Mandarin phrases.

The exchange turned tense and turned into a verbal altercation, but the clip went viral — by 11 PM on August 1, it had attracted over 154,000 likes and 18,000 comments, his highest engagement rate to date according to Newrank data. His other most-viewed posts have also centered on smoking dissuasion.

Many of Alibabame’s videos focus on discouraging smoking in public.

In a follow-up video shared on August 1, Alibabame said local police had given him a surprising interpretation of the rules: if someone smokes in a no-smoking area but extinguishes the cigarette after being asked, they are not breaking the law. Many viewers expressed disbelief, with comment sections filled with criticism and calls for stricter enforcement.

From Online Clashes to Court Cases

These recent viral clips have turned a niche activist effort into a broader discussion about how China’s anti-smoking regulations are interpreted — and whether enforcement can match public expectations.

Shanghai, for instance, has comprehensive smoking control rules Indoor public venues, workplaces, and public transport — including e-cigarettes — are fully smoke-free, with individuals facing fines of 50–200 yuan (US$7-US$28) and establishments up to 30,000 yuan (US$4180) for failing to prevent smoking. Outdoor bans cover spaces for children and teenagers, medical facilities, sports and performance venues, heritage sites, and transit stops.

Violations can be reported via the Public Service Hotline 12345 or other hotlines.

Earlier this year, Shanghai also became the first mainland city to target “wandering smoking (游烟)” control measures, banning smoking while walking in outdoor queues, sidewalks, and at popular spots such as the Bund and Wukang Road. Offenders face fines of up to 200 yuan ($28).

Despite these measures, ensuring smoke-free environments remains a problem in Shanghai and across other mainland cities.

Recent high-profile cases illustrate the difficulties. On July 3, Renwu magazine (人物) published an article titled “The ‘Lin Zexu of Universities’ and the War Against Secondhand Smoke” (“高校“林则徐”与二手烟的战争“), profiling Shang Mengmeng (尚萌萌), a Beijing film school graduate student with extreme nicotine sensitivity. After leaving jobs due to smoke exposure, he hoped campus life would be different, only to encounter smoking indoors, even in elevators and classrooms. Since March, Shang has filed about 120 complaints using cigarette butts and ash as evidence, earning him the nickname “Modern Lin Zexu” — referencing the Qing Dynasty official famed for his anti-opium stance.

Supporters praise his persistence, but Shang has also faced backlash from smokers accusing him of “extremism,” and even some non-smokers questioning his approach. Shang maintains he is not against smoking itself, only against smoking in prohibited areas, framing it as a matter of personal freedom versus public health rights.

On June 28, 2025, the Shenzhen Health Commission published an article titled “Secondhand Smoke Is Actually a Form of Bullying” (Image: Shenzhen Health Commission WeChat account).

Another case, reported by Southern People Weekly (南方人物周刊) on July 27, follows Jin Lanlan (金烂烂), a young woman assaulted in a mall after asking a man to stop smoking. On November 11, 2024, Jin confronted Tang, who responded with verbal abuse and a kick. Police fined Tang 200 yuan ($28), but he refused to apologize or compensate, prompting Jin to sue.

At a July 22 court hearing, Tang’s lawyer rejected all demands. Jin, who experienced secondhand smoke-induced vomiting as a child and left art school due to teachers smoking indoors, sees her actions as defending her legal rights. While some hail her as a “fighter,” others — including her own mother, who speaks of her “making trouble” — question her persistence.

The Road Ahead for Smoking Control in China

These court cases, along with the online discussions around the videos of foreign influencer ‘Alibabame,’ reveal long-standing obstacles to public smoking control on the mainland.

➤ Generational divides play a role: younger people are generally more aware of secondhand smoke risks, while some older smokers see it as a personal choice. Smoking also remains embedded in social customs, such as offering cigarettes at business or family gatherings.

➤ Misunderstandings about “freedom” and “rights” compound the problem, with some smokers prioritizing personal choice over non-smokers’ health rights, and many non-smokers staying silent to avoid further conflict.

➤ Enforcement is another weak point. Responsibility is split among multiple agencies, creating gaps in oversight. In smaller cities and rural areas, limited resources make it harder to police high-risk venues like restaurants and internet cafés. Low fines — as little as 50 yuan (US$7) in some places — do little to deter violations.

Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan provide contrasting examples, with much higher on-the-spot fines — HKD1,500 (US$190), MOP1,500 (US$186), and NTD2,000–10,000 (US$62–310) respectively — and dedicated enforcement bodies such as Hong Kong’s Tobacco and Alcohol Control Office.

As more mainland residents speak out, calls for stricter enforcement are growing. Some netizens have even urged Alibabame to involve international media like The New York Times to pressure authorities, but he has declined, stressing that this is a domestic issue and expressing confidence that Chinese authorities will act.

Whether this wave of public attention will push Shanghai toward tougher enforcement, and whether similar measures could spread to other mainland cities, remains uncertain.

What is certain is that smoking control will be a long-term challenge in China, requiring stronger enforcement, higher penalties, and, perhaps most crucially, a cultural shift that prioritizes clean air for non-smokers as much as the “freedom” of smokers.

Meanwhile, Alibabame’s follower count is climbing — he gained over 79,200 new followers since his viral video. His popularity suggests growing online support for smoking-dissuasion influencers, both foreign and Chinese, who are taking a stand for smoke-free public spaces.

Also Read:

- Zhang Yue, “China’s First Anti-Smoking Campaigner” (“中国第一反烟人”)

- Social Media Blows Up over Chinese Teen Celebrity Roy Wang Smoking in Beijing Restaurant

By Wendy Huang

Edited by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at

info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

What’s on Weibo is a reader-supported publication, run by Manya Koetse (@manyapan), offering independent analysis of social trends in China for over a decade. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

China Trend Watch: Naked Sleeping Woman Claims Depression After Being Seen by Window Cleaners

Online Debates About China’s Train Traditions: No More Instant Noodles or Cigarette Breaks?

China Trend Watch: From Lhasa to Labubu

Dialogues Across Time: Remembering War in a New China

Passing the Torch from ‘Ne Zha’ to ‘Nobody’: China’s Box Office Poster Relay Tradition

Hidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

The Next Labubu: What the Rise of Wakuku Tells Us About China’s Collectible Toy Wave

A Very Short Guide to China’s Most Popular Designer Toys

Popular Reads

-

China Memes & Viral1 month ago

China Memes & Viral1 month agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Books & Literature10 months ago

China Books & Literature10 months agoThe Price of Writing Smut: Inside China’s Crackdown on Erotic Fiction

-

China Society11 months ago

China Society11 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China Insight4 months ago

China Insight4 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal