China Digital

WeChat for the Workplace: The Rising Popularity of Enterprise App Ding Ding

A nightmare or handy work tool? Alibaba’s Ding Ding is gaining popularity across China.

Published

8 years agoon

While some call it a wonder tool, others say it’s a nightmare for employees. Ding Ding, Alibaba’s mobile and desktop app for companies, is gaining popularity across China. With its GPS-based features and other nifty functions, companies can now monitor the whereabouts of their employees.

It has been over 2,5 years since Alibaba launched its ‘enterprise app’ Ding Ding (钉钉). In February of 2015, websites such as TechCrunch and TechinAsia described the app as a new mobile and desktop program for businesses that aimed to compete with Tencent’s WeChat – China’s top messaging app.

At the time, Ding Ding (also known as DingTalk) was only available in Chinese. But the app, now updated to the 3.5.3 version, has become readily available in English on Chinese app stores, Google Play, and Apple stores.

Its use by companies across China is picking up. The app has now been downloaded 50.5 million times on the Huawei store, 27 million times on the Tencent app store, 20+ million times on the Oppo app store, 12 million times on the Baidu app store, and 8.5 million times on the 360 Mobile Assistant app store.

Smart mobile office

More companies across China are now using the app as a ‘smart mobile office’: it functions as a messaging app among colleagues, a tool for making conference calls, but more importantly, as a program that makes it easy for employees to clock in and out of work and for employers to check their whereabouts.

“Our company just started implementing it. Nobody gave us any warning,” an employee named Bryan Lee (alias) of a middle-sized Beijing educational company told What’s on Weibo this week: “I’ve spoken to many people of other companies here who also started to use it recently.”

Ding Ding has many functions, and in some ways is meant to replace WeChat as a work tool. The app allows users to create team groups, and also functions as an address book that shows the organizational structure of the company. Users can directly contact the HR group or other colleagues through Ding Ding.

According to Alibaba, ‘DingTalk’ is a “multi-sided platform” that “empowers small and medium-sized business to communicate effectively.” The app’s functions include, amongst others, the following features:

– Ding Ding is a global address book that allows users to view the organization’s structure in a glance and contact everyone, but also shows contacts outside of the company (suppliers, business partners, etc.) and functions as a customer information management system.

– The program is also a calendar for creating tasks and meetings.

– Ding Ding is an instant messaging app designed for office use, supporting both private and group chats and supporting file transfers. To improve communication efficiency, all types of messaging display read/unread statuses.

– The app’s ‘Ding It’ function makes sure recipients never miss a message by alerting them through phone, SMS, or in-app notification. Companies can also send out a voice message or hold a conference call to make sure their message is heard.

– The Secret Chat function works like SnapChat, making messages traceless and self-deleting for ultimate privacy and protection.

– Through its Smart Attendance System companies can keep track of employee’s attendance and overtime records; employees can clock-in and out of work in an instant. The software also automatically generates attendance reports.

– Ding Ding can process approvals by electronically dealing with request for leaves, business trips or reimbursements. Approvals for business trips and leave are automatically linked with attendance records.

– DingTalk is also a high-definition video conferencing system and allows users to also start free individual calls.

– Ding Ding has its own business cloud (or “Ding drive”) feature, making file saving and sharing a quick and easy task, also between PC and mobile.

– DingTalk’s email inbox also makes it possible to receive email notifications in chats.

Despite the myriad of functions, or actually because of them, some employees call the app a ‘catastrophe’ for office staff.

Big boss is watching you

“Since Ding Ding is GPS-activated, I will be signed in when I get to work. And when I leave work, it will clock me out,” Lee says.

The app’s clocking system is one of its most used functions and allows companies to track whether their employees arrive late at work or whether they are working overtime.

“Clock out successful. Got off work 18:04.”

There is a positive side to it for employees since there is much less paperwork to fill out when, for example, asking compensation for overtime work. Lee notes that people can also electronically apply for a leave of absence through Ding Ding.

But the downside is that there is no room for white lies anymore. Because of the app’s geotagging function, the employer can actually check if you really are seeing the doctor (as you said you were going to).

“Through Ding Ding you can report where you are for your company. If you requested a leave of absence to go to the hospital, for example, you can bookmark the location so that your company knows you really are at the location where you are supposed to be. Same goes for business-related appointments – if your company requires it, you tag the location so they can see that you are where you said you were going, so they won’t deduct your salary for that.”

“People have a lot of different views on it,” Lee says: “I am always at work when I need to be and I never cheat the system. So I think it is very convenient that I no longer need to take my phone and scan a QR code every day to log in to work, which used to be mafan [trouble] – this is much easier. But a lot of people think it is somewhat Orwellian. They do not monitor your everyday moves but if you actually go drinking with your friends instead of going to a doctor as you told your boss, then that might get you in trouble.”

Apart from the location-tagging function, which may or may not be required/activated by the company, there are also other functions that many people do not like. Ding Ding, unlike WeChat, automatically shows that your message has been delivered and read. It also allows a company to send out a ‘Ding alert’ (which notifies recipients through phone call/SMS/In-App alerts) to make sure everybody gets the message.

On Q&A platform Zhihu.com, user ‘Aurora’, who works at a HR company, tells how this has made life more troublesome for office staff:

“The rapid growth of Ding Ding lies in the fact that it meets the requirements of its user – the boss. Just imagine: you’re in the midst of finishing a proposal when the boss sends you a message saying you need to come over to bring them a certain file.

-

Before using Ding Ding:

1. You see the message. You finish the last part of your proposal before bringing over the file to your boss a bit later.

2. You don’t see the message. You finish your task and take a break. You then see the message and take care of it.

3. No matter if you see did or did not see the message, the boss notices you did not respond and gives you a call.

-

Since using Ding Ding:

1. You see the message. Your boss gets a ‘message read’ (已读) confirmation and you have no other option than to break off your work and immediately take care of it.

2. You haven’t seen it. So your boss sends you a ‘ding alert’ and you have no other option but to read it, break off your work, and immediately take care of it.”

Aurora also writes that Ding Ding is completely made to comply with the demands of the company’s managers rather than their staff. For office staff, it is not convenient to have to respond to the boss’s wishes immediately – it can disturb their everyday tasks and adds stress to their job. For the manager, on the other hand, it has become very easy to reach the staff: they do not even need to pick up the phone anymore, and can reach whoever they want right away.

Unhappy Dingers

On Weibo, many people share Aurora’s views and are not too happy with Ding Ding. “I’ve had enough with this app! It reminds me every single morning to clock in to work!”

“You have to be at work in 12 minutes, don’t forget to clock in!”

Others also complain that the app only adds to the time they spend looking at their phone: “If it’s not my QQ group, then it’s my WeChat group or my Ding Ding group – it seems I am looking at my phone screen all day,” one Weibo user says.

There are also people who note that they are hardly ever really free from work anymore. As one Xiamen worker writes: “I had the morning off. But I had hundreds of WeChat messages, dozens of Ding Ding messages, and three missed phone calls. This is ruining me.”

“With this Ding Ding app it seems like no matter what time it is or where you are, you’re just always at work,” another complaint said.

“It looks like they are going to implement Ding Ding at my office. I just want to punch the person who invented this app.”

But despite all the backlash and complaints, Ding Ding’s popularity as an office solution for immediate workplace communication and registering employee’s working hours is on the rise.

On the app’s review page on the Huawei store, some call it “the best office application.” Others also note that the app is not just convenient, but also free: “It is very practical, and it has saved me the costs for other office management software.”

Other reviewers also seem much more enthusiastic than the complaining netizens on Weibo: “In our office, it’s become an essential tool – and its functions just keep getting better and better.”

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Digital

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

A virtual Viagra for a pressured generation? The real story behind China’s latest viral app.

Published

3 weeks agoon

January 14, 2026

From censored joke to state-friendly app, ‘Are You Dead Yet?’ has traveled a long road before reaching the top of China’s paid app charts this week. While marketed as a tool for those living alone to check in with emergency contacts, the app’s viral success actually isn’t all about its features.

It is undoubtedly the most unexpected app to go viral in 2026, and the year has only just started. “Are You Dead?” or “Dead Yet?” (死了么, Sǐleme) is the name of the daily check-in app that surged to the No. 1 spot on Apple’s paid app chart in China on January 10–11, quickly becoming a widely discussed topic on Chinese social media. It has since become a top-searched topic on the Q&A platform Zhihu and beyond, and by now, you may even have noticed it appearing on your local news website.

For many Chinese who first encountered the app, its name caused unease. In China, casually invoking words associated with death is generally considered taboo, seen as causing bad luck. It was therefore especially noteworthy to see state media outlets covering the trend. The fact that the name plays on China’s popular food delivery platform Ele.me (饿了么, “Hungry Yet?”), a household name, may also have softened the linguistic sensitivity.

Beyond the name, attention soon shifted to the broader social undercurrents and collective anxieties reflected in the app’s sudden popularity.

🔹 “A More Reassuring Solo Living Experience”

Are You Dead Yet? is a basic app designed as a safety tool for people living alone, allowing them to “check in” with loved ones. The Chinese app has been available on Apple’s App Store since 2025 and currently costs 8 yuan (US$1.15) to download.

The app is very straightforward and does not require registration or login. Users simply enter their name and an emergency contact’s email address. Each day, they tap a button to virtually “check in.”

If a user fails to check in for two consecutive days, the system automatically sends an email notification to the designated emergency contact the following day, prompting them to check on the user’s safety.

The app was created by Guo Mengchu (郭孟初) and two of his Gen Z friends from Zhengzhou, all born after 1995. Together, they founded the company Moonlight Technology (月境技术服务有限公司) in March 2025, with a registered capital of 100,000 yuan (US$14,300). The app was reportedly developed in just a few weeks at a cost of approximately 1,000 yuan (around US$143).

In the text introducing the Dead Yet? app, the makers write that the app is specifically intended to “build seamless security protection for a more reassuring solo living experience” (“构建无感化安全防护,让独处生活更安心”).

🔹 The Rise of China’s Solo-Living Households

The number of solo households in China has skyrocketed over the past three decades. In the mid-1990s, only 5.9% of households in China were one-person households. By 2011, that number had nearly tripled from 19 million to 59 million, accounting for nearly 15% of China’s households.1,2 By now, the number is bigger than ever: single-person households account for over 25% of all family households.3

These roughly 125 million single-person households are partly the result of China’s rapidly aging society, along with its one-child policy. With longer life expectancies and record-low birth rates, more elderly people, especially widowed women, are living alone without their (grand)children.

China’s massive urban-rural migration, along with housing reforms that have adapted to solo-living preferences, has also contributed to the fact that China is now seeing more one-person households than ever before. By 2030, the number may exceed 150 million.

But other demographic shifts play an increasingly important role: Chinese adults are postponing marriage or not getting married at all, while divorce rates are rising. Over the past few years, Chinese authorities have introduced various measures to encourage marriage and childbirth, from relaxed registration rules to offering benefits, yet a definitive solution to combat China’s declining birth rates remains elusive.

🔹 A “Lonely Death”: Kodokushi in China

Especially for China’s post-90s generation, remaining unmarried and childless is often a personal choice. On apps like Xiaohongshu, you’ll find hundreds of posts about single lifestyles, embracing solitude (享受孤独感), and “anti-marriage ideology” (不婚主义). (A few years back, feminist online movements promoting such lifestyles actually saw a major crackdown.)

Although there are clear advantages to solo living—for both younger people and the elderly—there are also definite downsides. Chinese adults who live alone are more likely to feel lonely and less satisfied with their lives 4, especially in a social context that strongly prioritizes family.

Closely tied to this loneliness are concerns about dying alone.

In Japan, where this issue has drawn attention since the 1990s, there is a term for it: kodokushi (孤独死), pronounced in Chinese as gūdúsǐ. Over the years, several cases of people dying alone in their apartments have triggered broader social anxiety around this idea of a “lonely death.”

One case that received major attention in 2024 involved a 33-year-old woman from a small village in Ningxia who died alone in her studio apartment in Xianyang. She had been studying for civil service exams and relied on family support for rent and food. Her body was not discovered for a long time, and by the time it was found, it had decomposed to the point of being unrecognizable.

Another case occurred in Shanghai in 2025. When a 46-year-old woman who lived alone passed away, the neighborhood committee was unable to locate any heirs or anyone to handle her posthumous affairs. The story prompted media coverage on how such situations are dealt with, but it drew particular attention because cases like this had previously been rare, stirring a sense of broader social unease.

🔹 The Sensitive Origins of “Dead Yet?”

Knowing all this, is there actually a practical need for an app like Dead Yet? in China? Not really.

China has a thriving online environment, and its most popular social media apps are used daily by people of all ages and backgrounds, across urban and rural areas alike. There are already countless ways to stay in touch. WeChat alone has 1.37 billion monthly active users. In theory (even for seniors) sending a simple thumbs-up emoji to an emergency contact would be just as easy as clocking in to the Dead Yet? app.

The app’s viral success, then, is not really about its functionality. Nor is it primarily about elderly people fearing a lonesome death. Instead, it speaks to the dark humor of younger adults who feel overwhelmed by pressure, social anxiety, and a pervasive sense of being unseen—so much so that they half-jokingly wonder whether anyone would even notice if they collapsed amid demanding work cultures and family expectations.

And this idea is not new.

After some online digging, I found that the app’s name had already gone viral more than two years earlier.

That earlier viral moment began with a Zhihu post titled “If you don’t get married and don’t have children, what happens if you die at home in old age?” (“不结婚不生孩子,老后死在家中怎么办”). Among the 1,595 replies, the top commenter, Xue Wen Feng Luo (雪吻枫落), whose response received 8,007 likes, wrote:

💬 “You could develop an app called “Dead Yet?” (死了么). One click to have someone come collect the body and handle the funeral arrangements.”

The original post that started it all. That humorous comment was the initial play on words linked to food delivery app Eleme (饿了么).

Two days later, on October 8, 2023, comedy creator Li Songyu (李松宇, @摆货小天才), also part of the post-90s generation, released a video responding to the comment.

In it, he presented a mock version of the app on his phone: its logo a small ghost vaguely resembling the Ele.me icon, and its interface showing some similarities to ride-hailing apps like Uber or Didi.

In the video, Li says:

🗯️ “Are You Dead Yet?’ I’ve already designed the app for you. (…) The app is linked to your smart bracelet. Once it fails to detect the user’s pulse, someone will immediately come to collect the body. Humanized service. You can choose your preferred helper for your final crossing, personalize the background music for cremation and burial, and even set the furnace temperature so you can enter the oven with peace of mind. Big-data matching is used to connect people who might have known each other in life, followed by AI-assisted cemetery matching for the afterlife traffic ecosystem—you’ll never feel alone again. After burial, all content on your phone is automatically formatted to protect user privacy and eliminate worries about what comes after. There’s a seven-day no-reason refund, almost zero negative reviews, and even an ‘Afterlife Package’ with installment payments. Invite friends to visit the grave and have them help repay the debt. And if not everything turns to ashes properly, or if you’re dissatisfied with the shape of the remains, you can invite friends to burn them again and get the second headstone at half price! How about that? Tempted?”

The original “Sileme” or “Dead Yet” app idea, October 2023.

The video went viral, drew media coverage (one report called the concept and design of the “Are You Dead?” app “unprecedented”), and sparked widespread discussion. Although viewers clearly understood that the idea—one click and someone arrives to collect the body and arrange the funeral—was a joke, it nevertheless struck a chord.

Many saw the video as a glimpse into China’s future, arguing that with extremely low birth rates and a rapidly aging society, such business ideas might one day become feasible. Some people pointed to Japan’s growing problem of elderly people dying alone, suggesting that China may come to face similar challenges. At the same time, it also sparked concerns about increasing social isolation.

Despite its popularity, both the video and the trending hashtag “Dead Yet App” (#死了么APP#) were taken offline. A comedy podcast episode discussing the concept—“Did Someone Really Create the ‘Dead Yet’ App?” (真的有人做出了“死了么”APP?), released on October 10, 2023 by host Liuliu (主播六六)—was also removed.

According to Li Songyu himself, the video went offline within 48 hours “for reasons beyond one’s control” (“出于不可抗因素”), a phrase often used to avoid explicitly referring to top-down decisions or censorship.

It is not hard to guess why the darkly humorous Dead Yet? concept disappeared. And it wasn’t only because of crude jokes or the sensitivities surrounding death.

The video appeared less than a year after the end of China’s stringent zero-Covid policies, which had been preceded by protests. In both early and late 2023, Covid infections were widespread and hospitals were overcrowded. It was therefore a particularly sensitive moment to joke about bodies, afterlife logistics, and people being “taken away.”

Moreover, 2023 was a year in which state media strongly emphasized “positive energy,” promoting stories of heroism, self-sacrifice, and resilience in the face of hardship. It was not a time to dwell on death, and certainly not through humor.

🔹 Why a Censored Idea Became a ‘State-Friendly’ App

In 2025, things looked very different. Just weeks after the current Dead Yet? app was developed, it was released on the App Store on June 10, 2025. Not only was its name identical to the app “introduced” by Li in 2023, but its logo was also a clear lookalike.

The 2023 logo and 2025 “Dead Yet?” logo’s.

Although Li Songyu published a video this week explaining that he and his team were the original creators of the Dead Yet? concept and that they had planned to develop a real app before the idea was censored (without ever registering the trademark), app creator Guo Mengchu has simply stated that the inspiration for their app came “from the internet.”

In the same interview, Guo also emphasized that the app’s sudden rise was entirely organic, with the whole process of “going viral,” from ordinary users to content creators to mainstream media, taking about a day and a half.5

However, the app’s actual track record suggests a much bumpier journey.6 Since its launch, it has been taken down once and was reportedly removed from the App Store rankings three times. Such removals commonly occur due to suspected artificial download inflation, ranking manipulation, or other compliance-related issues.

After the most recent delisting on December 15, 2025, the app returned to the App Store on December 25—and only then did it finally have its breakthrough moment.

📌 Looking at how online discussions unfolded around the app, it becomes clear that, just as in 2023, the idea of relying on technology to ensure someone will notice if you die strongly resonates with people. Many users also seem to have downloaded it simply as a quirky app to try out. Once curiosity set in, the snowball quickly started rolling.

📌 But Chinese state media have also played a significant role in amplifying the story. Outlets ranging from Xinhua (新华) and China Daily (中国日报) to Global Times (环球时报) have all reported on the app’s rise and subsequent developments.

🔎 Why was Li Songyu’s Dead Yet? app idea not allowed to remain online, while Guo’s version has been able to thrive? The difference lies not only in timing, but also in tone. Li’s original concept leaned more clearly toward implicit social critique & satire. Guo’s app, by contrast, has been framed — and received — with far less overt sarcasm. While many netizens may still interpret it as dark humor, within official narratives it aligns more neatly with the family-focused social discourse, and perhaps even functions as an implicit warning: if you end up alone, you may literally need an app to ensure you do not die unnoticed.

In this way, the young creators of the new app are, perhaps inadvertently, contributing to an ongoing official effort in media discourse and local initiatives to encourage Chinese single adults to settle down and start a family. For them, however, it is a business opportunity: more than sixty investors have already expressed interest in the app.

Funnily enough, many single men and women actually hope to use the app to support their lifestyle. When, during the upcoming Chinese New Year, parents start nagging about when they will settle down, and warn that they might otherwise die alone, they can now reply that they’ve already got an app for that.

🔹 What’s in a Name?

Over the past few days, much of the discussion has centered on the app’s name, which is what drew attention to it in the first place. As interest in the app surged, fueled by international media coverage, criticism of the name also grew. Some found it too blunt, while public commentators such as Hu Xijin openly suggested that it be changed.

Considering that the mention of death itself carries online sensitivities in China, it’s possible that there’s been some criticism from internet regulators, and the Ele.me platform also might not be too pleased with the name’s resemblance.

Whatever the exact reasons, the app’s creators announced on January 13 that they would abandon the original name and rebrand the app as its international name ‘Demumu’ (De derived from death, the rest intentionally sounds like ‘Labubu’).

This marked a notable shift in stance: just two days earlier, one of the app’s creators had stated that they had not received any formal requests from authorities to change the name and had shown no apparent intention of doing so.

Most commenters felt that without the original name, the app doesn’t make sense. “As young people, we don’t care so much about taboo words,” one commenter wrote: “Without this name, the app’s hype will be over.”

On January 14, the creators then made another U-turn and invited app users to think of a new name themselves, rewarding the first user who proposes the chosen name with a 666 yuan reward ($95).

The naming hurdles suggest the makers are quite overwhelmed by all the attention. At the same time, dozens of competing apps have already appeared. One of them, launched just a day after Are You Dead Yet? went viral, is “Are You Still Alive?” (活了么), which offers similar basic functions but is free.

This new wave of similar apps has also led more people to wonder how effective these tools really are once the quirkiness wears off. One Weibo blogger wrote:

💬 “I really don’t understand why this app went viral. You can only check in daily, and you need to miss two consecutive check-in days for the emergency contact to be alerted. That means, if something actually happens, someone will only come after three days!! You’ll be rotting away in your home!!”

Others also suggested that it is clear the app was designed by younger people—the elderly users who might need it most would likely forget to check in on a daily basis.

🔹 Why “Dead Yet?” Is Like Viagra for a Pressured Generation

Amid the flood of Chinese media coverage, one commentary by the Chinese media platform Yicai7 stands out for pinpointing what truly lies behind the app’s popularity.

The author of the piece “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Dead Yet’ App” (in Chinese) argues that the app did not win users over because of its practical utility. Its main users are young people for whom premature death is an extremely low-probability event. They are clearly not downloading the app because they genuinely fear that “no one would know if they died,” nor are they likely to check in daily for such a tiny risk.

Since the app is clearly being embraced by users that do not belong to the actual target group, it must be providing some unexpected value.

💊 The author compares this unplanned function of the app to how Viagra was originally developed to treat heart disease. In this case, app users say that interacting with Dead Yet? feels like a lighthearted joke shared between close friends, offering a sense of social empathy and emotional release in a way that does not feel pressured.

Because the pressure—that’s the problem. Yicai describes just how multidimensional the pressures facing many young adults in China today can be: there is the economic challenge of the never-ending rat race dubbed “involution” along with uncertainty in the job market; there’s the “996” extreme work culture across various industries, leaving little room for private life; traditional family expectations that clash with housing and childcare costs that many find unattainable; and the world of WeChat and other social media, which can further intensify peer pressure and anxiety.

Of course, a lot has been written about these issues through the years. But do people really get it?

According to Yicai, there’s not enough understanding or support for the kinds of challenges young people face in China today. Even worse, older generations’ own past experiences often impose additional burdens on younger people, who keep running up against traditional notions while receiving inadequate support in areas such as education, employment, housing, marriage, family life, and even healthcare.

The author describes the unexpected viral success of Dead Yet? as a mirror with a message:

💬 “The viral popularity of ‘Are You Dead?’ seems like a darkly humorous social metaphor, reminding us to pay attention to the living conditions and inner worlds of today’s youth. For the young people downloading the app, what they need clearly isn’t a functional safety application, it’s a signal that what they really need is to be seen and to be understood—a warm embrace from society.”

Will the Dead Yet? app survive its name change? Is there a future for Demumu, or whatever it will end up being called? As it is now—the basic app with check-in and email or SMS functions—it might not keep thriving beyond the hype. If it doesn’t, it has at least already fulfilled an important function: showing us that in a highly digitalized, stressful, and often isolating society where AI and social media play an increasingly major role, many people yearn for the simple reassurance of being noticed, mixed with a shared delight in dark humor. Just a little light to shine on us, to remind us that we’re not dead yet.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Thanks to Ruixin Zhang & Miranda Barnes for additional research

1 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2013. “Living Alone in China: Historical Trends, Spatial Distribution, and Determinants.”

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Living-Alone-in-China-%3A-Historical-trend-%2C-Spatial-Yeung-Cheung/8df22ddeb54258d893ad4702124066b241bbdf8d.

2 Wei-Jun Jean Yeung and Adam Ka-Lok Cheung. 2015. “Temporal-Spatial Patterns of One-Person Households in China, 1982–2005.” Demographic Research 32: 1103–1134.

3 Li Jinlei (李金磊). 2022. “China’s One-Person Households Exceed 125 Million: Why Are More People Living Alone?”[中国新观察|中国一人户数量超1.25亿!独居者为何越来越多?]. China News Service (中国新闻网), January 14, 2022. https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cj/2022/01-14/9652147.shtml (accessed January 13, 2026).

4 Danan Gu, Qiushi Feng, and Wei-Jun Jean Yeung. 2019. “Reciprocal Dynamics of Solo Living and Health Among Older Adults in Contemporary China.”

The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 74 (8): 1441–1452. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby140.

5 Wang Fang (王方). 2026. “‘How We Went Viral: The Founder of the ‘Dead Yet?’ App Speaks Out’” [‘死了么’创始人亲述:我们是如何爆红的]. Pencil Way (铅笔道), interview with Guo (郭先生), published via 36Kr (36氪), January 13, 2026. https://www.36kr.com/p/3637294130922754 (accessed January 13, 2026).

6 Lü Qian (吕倩). 2026. “‘Am I Dead?’ App Price Raised from 1 Yuan to 8 Yuan, Previously Removed from Apple App Store Rankings Multiple Times”

[‘死了么从一元涨至八元,曾被苹果AppStore多次清榜’]. Diyi Caijing (第一财经), January 11, 2026. https://www.yicai.com/news/102997938.html (accessed January 14, 2026).

7 First Financial/Yicai (第一财经). 2026. “Behind the Viral Rise of the ‘Am I Dead?’ App: Young People Need a Hug” [‘死了么爆火背后,年轻人需要一个拥抱’]. Official account article, January 12, 2026. https://www.toutiao.com/article/7594671238464569899/ (accessed January 14, 2026).

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2026 Eye on Digital China/Powered by Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

From Hong Kong’s Wang Fuk Court fire and China’s new “family member” rule to Japanese concerts halted, the Nantong viral remark, childcare subsidy payouts, 6G trials, and top social media debates.

Published

2 months agoon

December 2, 2025

🔥 China Trend Watch — Week 48–49 (2025)

Part of Eye on Digital China. This edition was sent to our subscribers — subscribe to receive the next issue in your inbox.

Welcome to another edition of the China Trend Watch Eye on Digital China newsletter. I have been typing this newsletter from my phone and a tiny tablet on the trains from Chongqing to Wuhan and Wuhan to Nanjing, unfortunately tucked in the middle seat (that place where elbows suddenly become such inconvenient body parts), so please bear with me if spotting any inconsistensies or if the images don’t line up.

Chongqing has been a unique experience — a city in China that has been on my to-visit list for years. Its “cyberpunk” reputation doesn’t really do it justice. There’s this beautiful tension between its old history (century-old stairs, wartime tunnels) and the full speed of the future (neon lights, incredible skyscrapers), with the streets actually smelling like hotpot – such a special mix (or is that, perhaps, just what cyberpunk actually is?!).

Photos by me: View over Chongqing’s Shibati area, and toymachines in a wartime bomb shelter near Libazi.

This time, it was the city’s WWII history that finally pushed me to visit, as I’m on a research trip through several major cities that played important roles in China during the Second Sino-Japanese War — a topic that has become increasingly relevant over the past few months. I’ve already visited some fascinating places, from the former residence of General Stilwell to Chiang Kai-shek’s air-raid shelters and wartime military headquarters. Today I’ll be heading to some war-related museums in Nanjing. More on that later.

I will get back into my normal routine next week when I return from travels.

Let’s dive in.

- 🇨🇳 The 2025 Mnet Asian Music Awards (MAMA), one of the biggest K-pop award shows, sparked online backlash this week after netizens discovered that the event’s voting interface listed Hong Kong and Taiwan as separate countries in its selection menu. Seen as violating the ‘One China’ principle, netizens criticized MAMA for being disrespectful to China (meanwhile, the event was actually held in Hong Kong).

- 💰 As part of a national childcare subsidy plan announced earlier this year (initiated to boost China’s dropping birth rates and support low-income families), parents across the country are now receiving their initial 3,600 yuan ($508) payouts (per child aged 0–3 per year), creating an online buzz and reminding other parents to apply if they haven’t yet.

- 👀 Move over 5G…the 6G era is nearing! China has completed its first real-world testing trial of 6G applications. Being 100x faster than 5G, it’s the future mobile standard. Commercial use is planned for 2030.

- 🎬 Zootopia 2 is everywhere right now and has broken records in China with a US$267 million box office in 5 days. But despite its success there’s also been some backlash over the decision to cast celebrity actors for the main characters in the Chinese version instead of professional voice actors. Fans of the movie felt the performances were subpar, leading fans of the celebrities to defend them.

- 🚹 The 57-year-old Chinese actor and singer Sun Hao (孙浩) made headlines this week, and not for his latest work — but for getting caught urinating in public after a dinner with friends. The incident has triggered discussions about how (un)acceptable it is to pee on the street, and how celebrities should set the right example.

- 🛸 Blending classic Chinese humor with sci-fi elements, the new Chinese urban comedy Sarcastic Family (毒舌舌家) has become an online hit. The comedy is about a mother and daughter from another galaxy who become an unconventional family on planet Earth when the daughter marries a Chinese man, joined in a household by his father and her own outer-space mom.

1. The Hong Kong Wang Fuk Court Fire

The catastrophic residential fire at Hong Kong’s Wang Fuk Court in the city’s Tai Po district (香港大埔) has become the deadliest blaze in Hong Kong in 80 years.

The fire, which broke out on Wednesday at 14:51 local time, spread so quickly that it soon covered a total of seven residential towers. Initially, news came out that the fire had killed at least 13 and injured 28, but the figures soon kept rising. At the time of writing, the official death toll is 151, with 30 people still missing. A total of eleven people have now been arrested in relation to the fire, including two directors of the consultancy firm in charge of the renovation project that was taking place at Wang Fuk Court.

On Chinese social media, the fire has been top-trending news for days. One major point of discussion has been how the fire could have spread so rapidly; what started as a smaller blaze turned into an inferno within minutes. As part of exterior maintenance work, the buildings were covered in bamboo scaffolding and protective netting. Dry weather and strong winds contributed to the rapid spread. Residents said they had repeatedly seen construction workers smoking at the site.

Online conversations initially focused on the bamboo scaffolding, which is traditionally used in construction in Hong Kong for its flexibility and fire resistance. Soon, conversations shifted, blaming the flammable material used in the netting, as well as the styrofoam insulation used to seal windows. Although there are voices speaking out against misinformation regarding the flammability of bamboo, some commenters still point to the bamboo for intensifying the fire and making rescue operations more difficult.

Another issue is the fire system. A former security supervisor alleged the estate’s fire systems were frequently switched off. The claim, reported by local media, has intensified scrutiny and public concern over estate safety management.

What stands out in these discussions on the fire is that people are also tying it to deeper-rooted issues in Hong Kong. Since it’s Hong Kong, there’s arguably some more online room for discussion on such a topic. One Weibo blogger named ‘Jinshu Sister’ wrote: “The blaze exposed two very different worlds within ‘glamorous’ (光鲜) Hong Kong: one world is the fast-moving international metropolis, a playground for capital and elites. The other world consists of citizens living in decades-old buildings. Their hopes of improving their housing have been repeatedly delayed due to practical difficulties, such as costly maintenance fees and the complicated procedures of owners’ corporations. A truly great city is not defined by how many world-class skyscrapers it has, but by whether it can protect the life and safety of every ordinary person living in it.”

2. Living Together Now Counts as “Family Members”

Image by state media outlet CNR: “Living together before marriage is also belongs to [the category of] family members.”

The move is meant to protect victims of domestic abuse and help prosecute abusers within the context of the Anti-Domestic Violence Law. Forms of abuse beyond physical injury (e.g. mental abuse) will also be recognized as domestic violence.

The announcement has sparked heated debates as people began worrying about their current relationships being legally defined as a de facto marriage, with various implications regarding spousal obligations, property rights, and financial issues — including concerns that partners might suddenly be treated as legally responsible for each other’s debts. In recent years, there have been increasing discussions about women marrying to shift their personal debts onto their husbands (there’s even a word for it).

But legal experts on social media say there’s no need to panic: people still need to be legally married to be designated as an official married couple, with all marital obligations and benefits. They emphasize that the current revision is mainly meant to standardize the handling of domestic violence cases nationwide — especially at a time when more young Chinese are delaying marriage and choosing to live together. In the past, there have been cases of men severely abusing their live-in girlfriends, but because they were not legally married, such incidents were treated merely as “ordinary disputes among citizens.”

In light of the many trending stories over the past years concerning domestic violence, you might expect more support for this legal revision. However, people have doubts about how cohabitation will actually be defined in court. One commenter on Weibo wrote: “How should it be defined? If you have sex once a week, is that considered cohabitation? If you stay together for one week every month, is that considered cohabitation? If you have long-term sexual relations but leave after it’s over and don’t sleep together at night, is that cohabitation? There is only one answer: discretionary power (自由裁量权). If the judge says it is cohabitation, then it is cohabitation. Since cohabitation makes you ‘family members,’ can the other party then take half of the house?”

3. Japanese Concerts in China Hit by Sino-Japanese Tensions

Over the past weekend, video footage showing how a concert by Japanese artist Maki Otsuki was suddenly and quite dramatically stopped while she was singing on stage — the lights were turned off, her mic was taken away, and she was escorted off — popped up all over WeChat and beyond (see video on X), followed by various write-ups on the incident, which were soon taken offline.

Ayumi Hamasaki, another famous Japanese artist, also saw her Shanghai concert — 14,000 tickets sold — canceled just a day before the show. Although there was not a single audience member, she performed anyway, leaving her performing alone in an empty venue. She posted about it herself (see photos), expressing sadness over the elaborate stage setup prepared by 200 staff members over several days that now had to be dismantled without the concert ever taking place.

The “lights out” moment for Otsuki, Hamasaki, and many other Japanese artists and musicians in China was attributed to “force majeure” (因不可抗力) in venue statements coming from Beijing, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, and beyond. It comes amid heightened tensions between Japan and China following Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi’s November 7 remarks suggesting that Chinese actions regarding Taiwan could prompt a military defense response from Tokyo, which infuriated China for “intervening in China’s sovereignty” and has been an ongoing major topic ever since.

On December 1, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian responded to questions about the cancellations during a regular press briefing by saying that reporters should inquire with the Chinese organizers of these events instead — providing no comments on the official reasons behind the wave of abrupt cancellations, which appear to have stemmed from a sweeping directive from Chinese authorities to halt Japanese cultural events.

It’s not only the music and event industry that’s been affected by recent escalations. Chinese airlines have sharply reduced flights to Japan in December, and Japanese movie releases in China have been postponed as well.

There have been mixed reactions following the wave of cancellations. Despite anti-Japanese sentiments online, many people also feel this move unfairly impacts Chinese companies and consumers. Political commentator Hu Xijin addressed the issue, writing: “First, this demonstrates China’s resolve to strengthen sanctions against Japan by cancelling performances by Japanese artists coming to China, and that certainly generates a positive effect. But at the same time, Chinese performance companies will face costs from breaching contracts and from the upfront investments already made; the city of Shanghai and its transportation sector lose a piece of consumption; some audience members who had already traveled from other places to Shanghai are left with nothing; and many ticket holders, especially those who planned to travel from other cities, had their weekend plans disrupted. Taken together, all of these are losses on China’s side.”

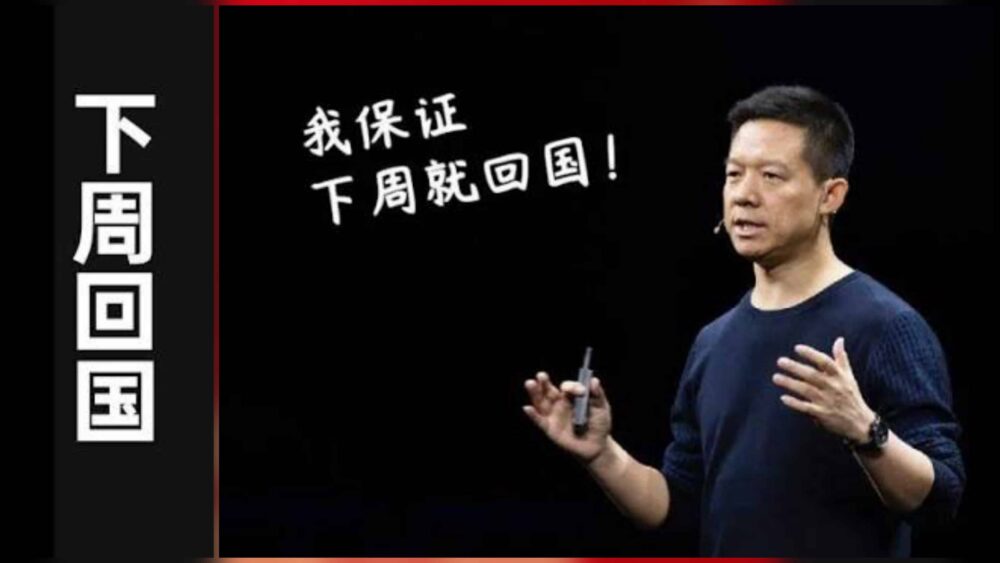

Returning to China next week [下周回国] (xià zhōu huíguó)

“Returning to China next week” has been a popular phrase for years in relation to tech entrepreneur Jia Yueting (贾跃亭), who departed China during the 2017 collapse of his LeEco tech company, leaving behind billions in debt.

While going on to found and lead EV startup Faraday Future (FF) in California, Jia repeatedly told Chinese audiences that he would return “next week.” When next week became next month, next year, and eventually never, “returning to China next week” became a running joke on social media, representing big promises with zero follow-up.

Now, Jia has again made headlines after announcing ambitious new plans for the future of FF and autonomous driving. Not only does Jia intend to cooperate with Tesla, he also said that FF and FX (the company’s second brand targeted at the mass market) have a five-year sales target of 500,000 cars. FF’s technology partner AIXC is the newly listed AI x Crypto company that is supposed to shake up the market. Jia’s business strategy has apparently pivoted to trying to create a tech + AI + crypto ecosystem in which each business strengthens the other.

Jia’s latest plans add to the series of grandiose promises that have made him a recurring character in Chinese online discussions. Although often mocked, there is also fascination in how Jia continues to stay in the headlines and attract new investments, seemingly without end.

Of course, after all this, netizens still wonder: “But will he still return to China next week?”

A screenshot showing a cheeky comment from an unexpected account has gone mega viral this week. The comment was made on Douyin by an official local government account in relation to a new law on sealing minor-offence records.

The revised section of the Public Security Administration Law, taking effect on January 1, 2026, adds the possibility of sealing certain administrative violations. Online, people mostly connected this to drug-related offences, wondering whether it would allow people whose names are tied to drug-related penalties to now have their records sealed.

Under a social media post about this issue, the official account of Nantong’s Culture & Tourism Bureau replied: “Which young master was caught using [drugs]?”(“哪位少爷吸了”), jokingly suggesting that the law has been introduced to protect certain individuals from powerful families.

The edgy remark sent the Nantong Tourism Bureau account’s followers up by nearly 1.5 million overnight, eventually adding a total of around 4 million new fans. And although the comment was soon deleted, it has boosted the visibility of Nantong, with some supporters suggesting that if its cultural bureau dares to make such bold remarks, the city itself might be worth a visit.

The moment shows that it only takes a tiny comment to go viral, and that, perhaps, Nantong now has a job opening for a new social media manager to entertain their millions of new followers with content that’s a bit less edgy.😅

Thanks for reading this Eye on Digital China China Trend Watch. For slower-moving trends and deeper structural analysis, keep an eye on the upcoming newsletters.

If you happen to be reading this without a paid subscription and appreciate my work, consider joining to receive future issues straight in your inbox.

Household notice: if you are receiving duplicate issues of this newsletter in your inbox, you are probably subscribed on both the main site and the Substack platform. For your own convenience, you can unsubscribe from one of them (let me know if you need help with that).

Many thanks and credits to Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang for helping curate the topics in this edition.

— Manya

Spotted an error or want to add something? Comment below or

email me. First-time commenters require manual approval.

©2025 Eye on Digital China / What’s on Weibo. Do not reproduce without permission —

contact info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Eye on Digital China is a reader-supported publication by

Manya Koetse (@manyapan) and powered by What’s on Weibo.

It offers independent analysis of China’s online culture, media, and social trends.

To receive the newsletter and support this work, consider

becoming a paid subscriber.

Get in touch

Have a tip, story lead, or book recommendation? Interested in contributing? For ideas, suggestions, or just a quick hello, reach out here.

China Trend Watch: From a Hospital in Crisis to Chaotic Pig Feasts

The “Are You Dead Yet?” Phenomenon: How a Dark Satire Became China’s #1 Paid App

Trump, Taiwan & The Three-Body Problem: How Chinese Social Media Frames the US Strike on Venezuela

China’s 2025 Year in Review in 12 Phrases

China’s 10 Biggest Social Media Stories of 2025

China Trend Watch: Japan Tensions, Nexperia Fallout, Yunnan’s ‘Wild Child,’ & “Modern Opium”

Eye on Digital China: How Chinese Social Media Evolved from the Blog Era to the AI-driven Age

Signals: Hasan Piker’s China Trip & the Unexpected Journey of a Chinese School Uniform to Angola

China Trend Watch: Hong Kong Fire Updates, Nantong’s Viral Moment & Japanese Concert Cancellations

About Eye on Digital China — Powered by What’s on Weibo

Popular Reads

-

China Arts & Entertainment7 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment7 months agoHidden Cameras and Taboo Topics: The Many Layers of the “Nanjing Sister Hong” Scandal

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoUnderstanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months ago“Jiangyou Bullying Incident”: From Online Outrage to Offline Protest

-

China Insight9 months ago

China Insight9 months agoChina Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West