China Arts & Entertainment

Weibo Night Awards: These Were The Most Influential Weibo Brands, Events & Celebrities

Weibo Night looks back on Sina Weibo’s hottest celebrities and happenings of the last year.

Published

8 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

The evening of January 16 was Weibo Night (#微博之夜#) – the yearly much-anticipated live-broadcasted ceremony that looks back on Sina Weibo’s hottest brands, celebrities, and happenings of the last year.

Weibo Night is an event that many netizens have been looking forward to for weeks. The night has been a recurring event since 2003, when the Sina media company first started the ceremony to look back on the hottest Weibo topics and celebrities of the previous year. The night was initially known as the ‘Sina Grand Ceremony’ (新浪网络盛典) until it turned into the ‘Weibo Night’ (微博之夜) in 2010.

During the ceremony of Weibo Night, that took place on the evening of January 16 (Beijing time) at the China National Convention Center, various prices were awarded in categories such as ‘The Hottest Weibo Person of the Year’, ‘Most Influential Weibo Musician of the Year’, ‘Weibo King & Queen’, ‘The Most Influential Companies’, or the ‘Biggest Topics of the Year.’

The award ceremony was broadcasted live on Weibo and received over 510,000 comments directly below the live broadcast on the Weibo Night account page. The hashtag ‘Weibo Night’ (#微博之夜#) was used over 28 million times.

The Biggest Events of the Year

While What’s on Weibo has compiled its own A-Z of the biggest trends on Weibo of 2016, the official Weibo Night jury picked some very different topics as the top events of the year – all of which focused on the Chinese nation.

The “retrial of Nie Shubin” (#聂树斌案再审#) was chosen as one of the biggest topics of the year. Nie was a young man who was executed in 1995 after being convicted for murder. After his family campaigned to prove his innocence for over two decades, the supreme court ruled in 2016 that there was “insufficient evidence” used in Nie’s trial, and his conviction was overturned. According to many Weibo commenters, the retrial proved that China’s legal system has made a lot of progress since the 1990s.

The topic “green channel for organ transportation” (#器官转运绿色通道#) also made it to the top events of the year according to the Weibo Night jury. The topic addresses the news that China established a “green organ channel” in 2016; a faster-prioritized transport system for human organs that will shorten the time it takes for organs to get to transplant patients, avoiding unnecessary health problems and delays. The topic made headlines in May of 2016, but actually only attracted a few thousand comments on Weibo.

According to the Weibo Night awards, the year’s biggest topic was “China Cannot Get Smaller” (#中国一点都不能少#), a slogan and image posted by state newspaper People’s Daily in July of 2016 around the time of the South China Sea trial that was brought to the tribunal in The Hague by the Philippines, which argued that Chinese activities in the disputed waters of the South China Sea are illegal.

The tribunal ruled that China’s sovereignty claims over the South China Sea indeed violated international law. The verdict angered many netizens and triggered a wave of cyber-nationalism.

The biggest Weibo topic according to the Weibo Night Awards.

The topic and image emphasizes that there is only One China, and that China includes Taiwan, Hong Kong and the disputed islands – and that there is no such thing as a ‘China’ that does not include these areas.

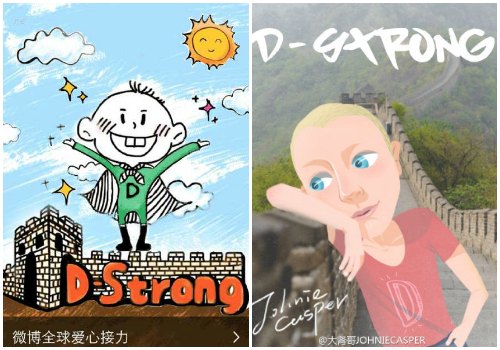

Other topics that were mentioned in the top event list were #D-STRONG, the election of Trump, the G20 summit, and the Beijing Hotel Assault.

DSTRONG became trending this year, as netizens celebrated the life of the terminally ill boy Dorian from the USA.

The divorce of Wang Baoqiang, which actually was one of the biggest topics of 2016, was not mentioned in the Weibo Night list. Shortly after the celebrity divorce and love scandal became one of the biggest topics on Weibo of 2016, the Chinese media watchdog announced that it would restrict the hyping of private scandals of the rich and famous.

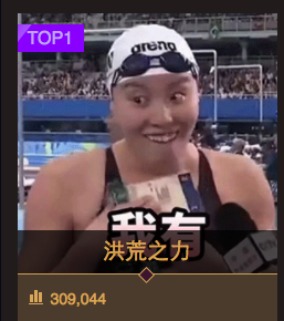

Swimmer Fu Yuanhui with her “mystical powers.”

In the Weibo Night ‘top hashtag list’, the catchphrase “mystical powers” (#洪荒之力#) came in first. The term became trending after Olympic swimmer Fu Yuanhui used it during an interview with the state media in Rio.

Weibo’s Most Popular Artists

This year, many of the Weibo People’s Awards went to celebrities in the music category. The Weibo celebrity that won the award for being most “Internationally Influential” was Hong Kong-born American singer-songwriter Coco Lee (李玟).

Chinese pianist Lang Lang (郎朗) was awarded the price for being Weibo’s Biggest Classical Musician, and Taiwanese pop singer Zhang Xinzhe (张信哲) a.k.a. Jeff Chang was awarded with the ‘model singer’ award. Jason Zhang (张杰) won the award for Best Concert of the Year.

The award for Most Popular Singer of the Year went to Chinese rapper Z.Tao (黄子韬), who also won the Most Influential Male Singer award at the 2016 Miaopai Awards.

Lang Lang, Coco Lee and Zhang Xinzhe on stage with their awards.

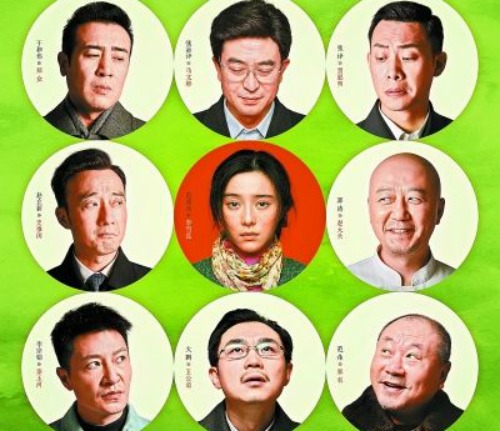

The Director of the Year award went to Feng Xiaogang (冯小刚) who produced the 2016 movie I Am Not Madame Bovary (我不是潘金莲). Feng was actually awarded twice this evening, as his film also became Weibo’s Best Movie of the Year.

I Am Not Madame Bovary by Feng Xiaogang became Weibo’s Best Movie of the Year.

Actresses Zhou Dongyu (周冬雨) and Ma Sichun (马思纯) were selected as winners in the Most Popular Performer category. Both women starred in the 2016 movie Soul Mate (七月与安生).

Most Influential People on Weibo

One of the most influential persons of the year, according to the Weibo Night awards, does not come as a surprise: Papi Jiang (papi酱) is the Weibo vlogger who had her big breakthrough last year with her witty online videos in which she commented on anything from family interactions to dating etiquette. In April 2016, an ad auction showed that companies were willing to pay up to 22 million RMB (3,4 million US$) to get Papi Jiang connected to their brand.

Papi Jiang, the biggest Chinese online celebrity of 2016.

The other ‘most influential’ person was Chinese table tennis player Zhang Jike (张继科), who became the number four player in the world in 2016.

In the sports category, Chinese Olympic swimmer Sun Yang (孙杨) was awarded as Best Sportsman of the Year.

Biggest Brands of the Year

Perhaps the selection of Weibo’s biggest brands of the year during this ceremony was not completely unbiased, as many of the chosen brands were also official sponsors of the show, such as Chinese electronics manufacturer Oppo or Japanese car brand Nissan.

Nissan, official sponsor of Weibo Night.

Other selected brands were e-commerce platform Jumei (聚美优品), Alibaba (阿里), Chinese smartphone and electronic brands Huawei (华为) and Xiaomi (小米), and ride-hailing app Didi (滴滴).

Especially Didi made headlines last year when it merged with its American rival Uber. Recently, the original Uber app has closed down and was replaced by an app specially made for the Chinese market.

Weibo King & Queen

One of the most anticipated awards of the night was that of the absolute ‘King’ and ‘Queen’ of Weibo – a People’s Choice Award that netizens could vote for in the weeks preceding the event.

Chinese actress Fan Bingbing (@范冰冰) was elected Weibo Queen. The actress has been among the top 10 of celebrities with the most Weibo followers for years. The 35-year-old celebrity is one of China’s most famous fashion icons and actresses. She is also the 4th highest-paid actress in the world. She currently has over 55.1 million Weibo fans, and received over 14 million votes for the title of ‘Weibo Queen’ for this year.

The Weibo ‘King’ of the year is pop group ‘TF Boys’, that received nearly 63 million votes for the ‘King’ award. The all-boy pop group has a huge fanbase in China. 2016 marked their first performance during China’s most prestigious live event – the CCTV Chinese New Year Gala, of which the 2017 Gala will be aired later this month.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow on Twitter or Like on Facebook

What’s on Weibo is an independent blog. Want to donate? You can do so here.

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Arts & Entertainment

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

From China’s first soap opera Yearnings to the rise of AI-fueled nostalgia.

Published

1 day agoon

July 2, 2025

The year is 1990, and the streets of Beijing’s Fangshan District are eerily quiet. You can almost hear a pin drop in the petrochemical town, as tens of thousands of workers and their families huddle around their televisions, all tuned to the same channel for something groundbreaking: China’s very first soap opera, Yearnings (渴望 Kěwàng).

Yearnings tells the story of Liu Huifang (刘慧芳), a female factory worker from a traditional working-class family in Beijing, and her unlikely marriage to university graduate Wang Husheng (王沪生), who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Liu finds an abandoned baby girl, she adopts her and raises her as her own, against her husband’s wishes.

The couple is unaware that the foundling is actually the illegitimate child of Wang’s snobbish sister, Yaru. After Liu and Wang have a biological son, the marriage comes under further pressure, eventually leading to divorce. Liu is left as a single mother, raising two children on her own.

Still from Yearnings, via OurChinaStory.

Drawing inspiration from foreign dubbed television shows, Yearnings was produced as China’s first truly domestic, long-form indoor television drama. Spanning 50 episodes, the series traces a timeline from the onset of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s through to the late 1980s—one of the most turbulent periods in modern Chinese history.

Before the series aired nationally on CCTV and achieved record viewership, the first station to air Yearnings in the Beijing region was the Yanshan Petrochemical TV Station (燕山石化电视台), China’s first major factory TV station (厂办电视台) located in Fangshan District.

Here, in this town of over 100,000, Yearnings garnered an astonishing and unprecedented 98% audience share. The series was truly groundbreaking and became a national sensation—not just because it was China’s first long-form television drama, or because it was a locally produced drama that challenged the long-standing monopoly of state broadcaster CCTV, but because Yearnings marked a major shift in television storytelling.

Until then, Chinese TV stories had always revolved around communist propaganda, or featured great heroes of the revolution. Yearnings, on the other hand, was devoid of political content and focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary people and their everyday struggles—love, desire, marital tension, single motherhood—topics that had never before been so openly portrayed on Chinese television.

The show’s creators had perfectly tapped into what was changing: the Communist Party was slowly withdrawing from private life, and people were beginning to see themselves less defined by their work unit and more by their home life—as consumers, as partners and parents, as citizens of a new China filled with aspirations for the future. Yearnings’ storyline was a reflection of that.

Chinese-Style “Nostalgia Core”

Yearnings marked a cultural turning point, coinciding with the rapid spread of TV sets in Chinese households. In 1992, economic reforms triggered a new era in which Chinese media became increasingly commercialized and thriving, before the arrival of the internet, social media, and AI tools once again changed everything.

Today, Yearnings still is a topic that often comes up in Chinese online media. On apps like Douyin, old scenes from Yearnings are reposted and receive thousands of shares.

📌 It’s emblematic of a broader trend in which more netizens are turning to “nostalgia-core.” In Chinese, this trend is known as “中式梦核” (Zhōngshì Mènghé), which literally means “Chinese-style dreamcore.”

Dreamcore is an internet aesthetic and visual style—popular in online communities like Tumblr and Reddit—that blends elements of nostalgia, surrealism, and subconscious imagery. Mixing retro images with fantasy, it evokes a sense of familiarity, yet often feels unsettling and deserted.

The Chinese-style dreamcore (中式梦核), which has become increasingly popular on platforms like Bilibili since 2023-2024, is different from its Western counterpart in how it incorporates distinctly Chinese elements and specifically evokes the childhood experiences of the millennial generation. Content tagged as “Chinese-style dreamcore” on Chinese social media is often also labeled with terms like “nostalgia” (怀旧), “childhood memories” (童年回忆), “when we were little” (小时候), and “Millennial Dream” (千禧梦).

According to the blogging account Yatong Local Life Observer (娅桐本地生活观察), the focus on the millennial childhood can be explained because the formative years of this generation coincided with a decade of rapid social change in China —leaving little in today’s modern cities that still evokes that era.

🌀 Of course, millennials in the West also frequently look back at their childhood and teenage years, particularly the 1980s and 1990s—a trend also embraced by Gen Z, who romanticize these years through media and fashion. In China, however, Gen Z is at the forefront of the “nostalgia-core” trend, reflecting on the 1990s and early 2000s as a distant, almost dreamlike past. This sense of distance is heightened by China’s staggering pace of transformation, modernization, and digitalization over the past decades, which has made even the recent past feel remote and irretrievable.

🌀 Another factor contributing to the trend is that China’s younger generations are caught in a rat race of academic and professional competition, often feeling overwhelmed by the fast pace of life and the weight of societal expectations. In this high-pressure environment—captured by the concept of “involution” (内卷)—young people develop various coping mechanisms, and digital escapism, including nostalgia-core, is one of them. It’s like a cyber-utopia (赛博乌托邦).

🌀 Due to the rise of AI tools available to the general public, Chinese-style nostalgia core has hit the mainstream because it’s now possible for all social media users to create their own nostalgic videos and images—bringing back the 1990s and early 2000s through AI-generated tools, either by making real videos appear more nostalgic or by creating entirely fictional videos or images that recreate scenes from those days.

So what are we seeing? There are images and videos of stickers kids used to love, visuals showing old classrooms, furniture, and children playing outside, accompanied by captions such as “we’re already so far apart from our childhood years” (example).

Images displayed in Chinese Dreamcore.

And notably, there are videos and images showing family and friends gathering around those old big TVs as a cultural, ritualized activity (see some examples here).

Stills from ‘nostalgia core’ videos.

These kinds of AI-generated videos depict a pre-mobile-era family life, where families and communities would gather around the TV—both inside and outside—from classrooms to family homes. The wind blows through the windows, neighbors crack sunflower seeds, and children play on the ground. Ironically, it’s AI that is bringing back the memories of a society that was not yet digitalized.

Nowadays, with dozens of short video apps, streaming platforms, and livestream culture fully mainstream in China—and AI algorithms personalizing feeds to the extreme—it sometimes feels like everyone’s on a different channel, quite literally.

In times like these, people long for an era when life seemed less complicated—when, instead of everyone staring at their own screens, families and neighbors gathered around one screen together.

There’s not just irony in the fact that it took AI for netizens to visualize their longing for a bygone era; there’s also a deeper irony in how Yearnings once represented a time when people were looking forward to the future—only to find that the future is now looking back, yearning for the days of Yearnings.

It seems we’re always looking back, reminiscing about the years behind us with a touch of nostalgia. We’re more digitalized than ever, yet somehow less connected. We yearn for a time when everyone was watching the same screen, at the same time, together, just like in 1990. Perhaps it’s time for another Yearnings.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Sources (other sources included in hyperlinks)

Koetse, Manya. 2016. “From Woman Warrior to Good Wife – Confucian Influences on the Portrayal of Women in China’s Television Drama.” In Stefania Travagnin (ed), Religion and Media in China. New York: Routledge.

Rofel, Lisa B. 1994. Yearnings: Televisual Love and Melodramatic Politics in Contemporary China. American Ethnologist 21(4):700-722.

Wang, Dan (汪丹). 2018. “《渴望》的艺术价值” [The Artistic Value of Yearnings].” Originally published in Beijing Daily (北京日报), October 12, 2018. Reprinted in Digest News (文摘报), October 20, 06 edition. Also see Sohu: 当年红遍大江南北的《渴望》.

Wang Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, a Chinese television soap opera with a message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Zhuge Kanwu. 2021. “重温1990《渴望》:苦得“刘慧芳”希望被导演写“死” [Revisiting 1990’s Yearnings: The Suffering Liu Huifang Hoped to Be Written Off by the Director]. Zhuge Dushu Wu (诸葛读书屋), January 22. https://wapbaike.baidu.com/tashuo/browse/content?id=b699ee532cf79f862bfa14ad.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Celebs

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Published

7 days agoon

June 27, 2025

🔥 Quick Take: Trending in China

This is a brief update from our curated roundup of what’s trending in China this week. A version of this story also appears in the Weibo Watch newsletter. Subscribe to stay in the loop.

Chinese beauty influencer and livestreamer Du Meizhu (都美竹) is facing online backlash this week after a former female fan filed a police report accusing her of scamming her out of nearly 200,000 yuan (approx. US$27,800).

The fan, known online as Sister Bing (Weibo handle @冰点人a冰点), has come forward with detailed allegations, claiming Du began swindling her in 2022.

Du Meizhu rose to national prominence in 2021 when she was 19 years old and became the first person to publicly accuse Chinese-Canadian pop star Kris Wu (吴亦凡) of rape and sexual misconduct. After at least 24 more victims also came forward, Wu was formally arrested on suspicion of rape in mid-August 2021 and was later sentenced to 13 years in prison.

It was around this time that ‘Sister Bing,’ whose real name is Ms. Zhu (朱, born 1979), started following Du Meizhu on social media. As a hard-working single mother of a daughter, she said she sympathized with Du and wanted to show her some support. In a Weibo post published in 2024, she detailed how Du Meizhu began noticing Zhu’s online interactions in early 2022 and added her as a friend on WeChat.

In private conversations, Du shared complaints about her difficult life, and as the two talked more and more, Zhu began transferring small amounts of money to help. Over time, Du said she needed money for various things—from financial support for school to legal disputes and expensive medical treatments for family members. Between 2022 and 2023, Zhu claims she transferred nearly 200,000 yuan in total.

At the end of 2023, Zhu–who works as a taxi driver–urgently needed money due to a family crisis. She reached out to Du to ask if she could repay the money. According to Zhu, she only returned 30,000 yuan (US$4,180) and refused to pay more, even though at the same time, Du was allegedly flaunting luxury brand purchases and had plans to buy a villa.

On June 25, 2025, Zhu posted an update on her Weibo account, saying she had traveled to Ulanhot City in Inner Mongolia – Du’s hometown – to seek justice and report the case to local authorities.

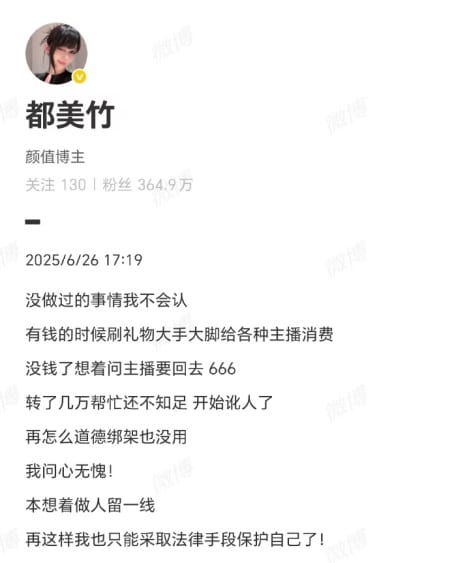

Du Meizhu has responded to the allegations on social media, writing that she “won’t admit to things I haven’t done.” She does not deny that Zhu gave her money.

She writes: “When she had money, she was lavishly spending it on gifts in all kinds of livestreams. Now that she’s broke, she wants it back from the streamers? After I transferred her thousands of yuan, she’s still not satisfied and is now starting to extort me. No amount of moral pressure will work. I have a clear conscience!”

The post by Du Meizhu

The case has blown up online. One post by Ms. Zhu has already received over 133,000 likes and is still gaining traction.

But the developments surrounding the case are puzzling to some. Du Meizhu has long maintained a social media image of wealth, showcasing a lifestyle filled with Dubai travel, horseback riding, luxury food, and fashion. Why would she need to take money from a single mum? Du is being criticized not only for faking her wealth, but also for accepting so much money from a woman who clearly needed the money for her own family.

Du Meizhu social media photos.

Although the story is attracting a lot of attention online because it exposes private conversations between Du and the woman – and, frankly, many netizens just enjoy the drama, – it also says a lot about China’s thriving livestreaming industry and just how close online followers can feel to the influencers they follow. In these kinds of online communities, it is common for fans and followers to send livestreamers money or ‘virtual gifts’.

In the case of Ms. Zhu, some netizens doubt that she can prove in court that she loaned Du the money instead of gifting it to her. People also criticize Zhu: why did she spend so much money on an online influencer instead of on her own daughter?

Either way, many Chinese netizens feel that it was not right of Du Meizhu to take advantage of a single mum like that. Even if she’s not legally wrong, they feel she lacks moral integrity.

Du’s most recent social media post—featuring her in so-called “old money fashion” outfits—has only added fuel to the fire. Dozens of commenters flooded the post with demands that she repay Ms. Zhu. Though Du seemingly tried to delete the negative comments, they kept pouring in. “At this rate, there won’t be any comments left,” one user wrote.

Whether or not Du Meizhu ultimately faces legal consequences, the backlash is already taking a toll. She might escape the courtroom, but won’t be able to escape the court of public opinion.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2025 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Jiehun Huazhai (结婚化债): Getting Married to Pay Off Debts

Yearnings, Dreamcore, and the Rise of AI Nostalgia in China

Beauty Influencer Du Meizhu Accused of Scamming Fan Out of $27K

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

Lured with “Free Trip”: 8 Taiwanese Tourists Trafficked to Myanmar Scam Centers

China Is Not Censoring Its Social Media to Please the West

IShowSpeed in China: Streaming China’s Stories Well

Inside the Labubu Craze and the Globalization of Chinese Designer Toys

China Reacts: 3 Trending Hashtags Shaping the Tariff War Narrative

China Trending Week 15/16: Gu Ming Viral Collab, Maozi & Meigui Fallout, Datong Post-Engagement Rape Case

Chinese New Nickname for Trump Mixes Fairy Tales with Tariff War

Strange Encounter During IShowSpeed’s Chengdu Livestream

No Quiet Qingming: From High-Tech Tomb-Sweeping to IShowSpeed & the Seven China Streams

Understanding the Dr. Xiao Medical Scandal

From Trade Crisis to Patriotic Push: Chinese Online Reactions to Trump’s Tariffs

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Media12 months ago

China Media12 months agoA Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

-

China Society9 months ago

China Society9 months agoDeath of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

-

China Memes & Viral12 months ago

China Memes & Viral12 months agoThe “City bu City” (City不City) Meme Takes Chinese Internet by Storm

-

China World11 months ago

China World11 months agoChina at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media