China Memes & Viral

China’s Trending Terminology: Top 25 Buzzwords and Catchphrases of 2023

Which words and phrases made it to Weibo’s top trending lists in 2023? We’ve compiled a top 25 of the most popular and noteworthy buzzwords.

Published

7 months agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT

Here are 25 Chinese buzzwords and catchphrases, listed by What’s on Weibo, that reflect social trends and changing times in China in 2023.

At the end of every year, Chinese media outlets usually compile a list of the most noteworthy buzzwords or the words that made the most impact during the year.

The most popular new words and expressions are generally listed by the Chinese linguistics magazine Yǎowén Jiáozì (咬文嚼字), which selects ten noteworthy buzzwords (十大流行语). On social media, Chinese online (state) media always promote the magazine’s selection of the top words and terms of the past year, but there are also other outlets selecting their top words of 2023, which have become a relatively big topic on Weibo over the past month.

In previous years, we’ve also published several articles in which we have listed the most important buzzwords.

◼︎ In 2018: China’s Top Ten Buzz Words & Phrases of 2018

◼︎ In 2019: Top 10 Buzzwords in Chinese Online Media 2019

◼︎ And in 2020: The Top 10 Buzzwords in Chinese Online Media in 2020 (咬文嚼字)

◼︎ And for 2020-2023, we also compiled this big Covid-19 vocabulary list.

If you want to know more about the buzzwords that made it to Chinese (official) media’s lists this year, check out this post by Andrew Methven at Slow Chinese which is a top ten compilation of Chinese buzzwords of 2023 based on these lists.

Top 10 Buzzwords by Yǎowén Jiáozì

The top 10 by Yǎowén Jiáozì consists of the following words:

1. 新质生产力 (Xīn zhì shēngchǎnlì)

This refers to “new quality productivity,” a term introduced by Xi Jinping this year focusing on a form of production driven by technological innovation as a new engine for China’s economic developmentin the new era. It covers technological innovation, new forms of energy, emerging industries and their interaction and integration, especially progress in digitalization, intelligence and green development.

2. 双向奔赴 (Shuāngxiàng bēnfù)

This means “running towards each other” or “devote efforts from both directions.” The phrase has become frequently used by Chinese netizens in the context of romantic love, meaning both sides are equally involved and putting in all effort to keep the love alive (双向奔赴的爱情).

3. 人工智能大模型 (Réngōng zhìnéng dàmóxíng)

“Large Scale Artificial Intelligence Models,” refering to the series of AI applications that we saw rising this year, including ChatGPT and Ernie Bot.

4. 村超 (Cūn chāo)

This term means “Village Super League,” a soccer event in Rongjiang County, Guizhou Province, organized by local villagers. It gained significant attention this year, drawing passionate new fans and showcasing China’s vibrant rural sports scene.

5. 特种兵式旅游 (Tèzhǒng bīngshì lǚyóu)

It means “special forces-style tourism”: special forces travelers have been flooding popular tourist spots across China. Their mission is clear: covering as many places as possible at the lowest cost and within a limited time. While the travel trend has become a social media hype, there are also those criticizing the trend for being superficial and troublesome (read here).

6. 显眼包 (Xiǎnyǎn bāo)

A goof, the life of the party, the class clown; the term “显眼包” in Chinese refers to someone or something that stands out from the crowd or grabs attention. While it previously had a negative meaning, standing out from the group is now also seen as having a goofy, bubbly and enjoyable personality that brings happiness.

7. 搭子 (Dāzǐ)

Dāzǐ translates to “companion,” “buddy,” “mate,” or “partner,” typically referring to someone you hang out with for particular activities who is not your significant other. You can have a “coffee buddy” (咖啡搭子), drinking buddy (酒搭子), or a “travel buddy” (旅游搭子). Chinese media have described the word as reflecting a new social trend among young people who might be single but still find various ways to have a satisfying social life that suits their needs.

8. 多巴胺×× (Duōbā’àn ××)

Dopamine is associated with happy hormones – pleasure and reward in the brain, and “××” indicates it’s being used in various contexts or activities related to pleasure or enjoyment. The term popped up this year in the context of ‘happy hormone fashion’ or ‘dopamine dressing’ (duōbā’àn chuāndā 多巴胺穿搭) the art of wearing colorful clothes to foster a good mood and positive vibes. Now, the use of ‘dopamine xxx’ is also used in other contexts.

9. 情绪价值 (Qíngxù jiàzhí)

This refers to “emotional value,” and is originally used within marketing to refer to the impact of consumers’ emotions on the products and services they purchase. This year, the word became more important as Chinese (young) consumers are shifting from merely ‘buying to use’ to actively participating and immersing themselves in experiences, such as the ‘special forces tourism’ (also in this list), city walks, enjoying Zibo barbecue, or purchasing virtual products that bring some kind of emotional value to them.

10. 质疑××,理解××,成为×× (Zhìyí ××, lǐjiě ××, chéngwéi ××)

This phrase means “question, understand, and become,” popularized because of the Chinese TV series iPartment (爱情公寓, ài qíng gōng yù). Initially, viewers questioned the female lead’s decision to prioritize her career over marriage. However, with time, they began to understand her perspective and realized that romantic love isn’t the sole priority. This pattern can also apply to various other scenarios and settings where initial doubts give way to comprehension and acceptance.

Top 25 Buzzwords/Catchphrases by What’s on Weibo

Here, we have made a special What’s on Weibo top 25 of top buzzwords and catchphrases of 2023. Most of these words have previously been featured in our premium Weibo Watch newsletter, where we select a word of the week for each issue.

These words are not in order of popularity, but rather in order of appearance throughout the year.

#1: FINAL-ROUND PLAYERS

Juésàiquān Xuǎnshǒu (决赛圈选手)

Over three years after the Covid-19 outbreak in China, it became increasingly uncommon to find people who hadn’t tested positive for the virus. After China eased its strict ‘Zero Covid’ measures in December 2022, infections surged across the nation, peaking in January 2023. By late January, over 80% of China’s population had contracted Covid. During the 2023 Spring Festival travel period, individuals wearing full protective gear stood out and attracted attention. During this time, Chinese media and netizens began calling those who remained Covid-free since 2020 the “final-round players” (决赛圈选手), suggesting that they were like finalists in the last round of the ‘avoid getting Covid’ game (read more).

#2: WANDERING BALLOON

Liúlàng qìqiú (流浪气球)

The ‘Wandering Balloon’ – liúlàng qìqiú 流浪气球 – emerged as a notable buzzword in February 2023 among Chinese netizens as the so-called ‘balloon incident‘ sparked an international dispute. The incident revolved around the U.S. military shooting down a Chinese balloon off the Carolina coast. While the U.S. labeled it a spy balloon, China contended it was a civilian “airship” (“飞艇”) for weather monitoring that drifted off course due to wind. On Chinese social platforms, this incident linked the balloon to the box-office hit The Wandering Earth II, leading to humorous online discussions. After reports of the balloon being shot down surfaced, some Weibo users playfully mourned the “poor baby balloon,” suggesting it was abruptly brought down without its chance to roam freely. The connection between the balloon incident and the sci-fi film’s popularity wasn’t surprising, given the movie’s enormous popularity and considering its narrative is all about catastrophic events and the future of international society. Read more about the incident and the words used here.

#3: BLIND WORSHIP OF FOREIGN GOODS/IDEAS

Chóng Yáng Mèi Wài (崇洋媚外)

This word/expression has come up a lot this year and specifically was used a lot when one incident went absolutely viral. In February of 2023, a Chinese associate professor named Chen Hongyou (陈宏友) stirred major controversy for remarks made during a speech at a school in Hefei, Anhui. According to various blogs and social media posts, Chen basically talked about how mixing races – ‘the further apart partners live, the better’ – would provide better genes for the next generation. He is also said to have suggested that his son, now living in the US with an American wife, would have children with better genes. In the middle of his speech, a student in the audience stormed to the stage and accused the professor of “worshipping foreign things and bowing to foreign powers [崇洋媚外].” This phrase, chóngyáng mèiwài, the popped up in hundreds of online discussions following the incident. Read more about that here.

#4: TOXIC TEXTBOOKS

Dú Jiàocái (毒教材)

Over the past few years, school textbooks that are deemed harmful or contain content that is perceived as offensive, unpatriotic, vulgar, or unsightly have received a lot of attention in China. Remember the ugly textbook scandal of 2022? Or the sexual education textbook of 2017? This year, the term ‘toxic textbook’ or ‘poisonous textbook’ – dú jiàocái 毒教材 – went trending on Weibo after famous commentator/writer Sima Nan made a video in which he warned about the return of the toxic textbooks. Issues highlighted include a geography textbook featuring Japan’s Mount Fuji instead of Chinese landmarks, illustrations depicting Japanese families over Chinese ones, maps omitting Taiwan from Chinese territories, and even primary school books with QR codes leading to inappropriate content. Concerned parents are urging authorities to take decisive actions to ensure the quality and appropriateness of school materials.

#5: RECOVER FROM COVID

Yángkāng (阳康)

As the worst peak of China’s 2023 Covid outbreak had ended by March of 2023, the word used to say ‘recover from Covid’ became a popular online phrase. This novel word is a combination of 阳 yáng, meaning [to test] ‘positive,’ and the word 康 kāng meaning ‘healthy.’ The word is also a pun based on a character in Jin Yong’s martial novel The Legend of the Condor Heroes, namely 杨康 Yáng Kāng. New language travels fast, and by now, the word has already become ingrained in everyday life. Some hospitals even opened their own “Covid Yangkang Clinics” (新冠阳康门诊) to help patients who are still suffering from symptoms after testing negative.

#6: DISCOURSE TRAP

Huàyǔ Xiànjiǎng (话语陷阱)

The “discourse trap” (话语陷阱) came up in relation to the speech made by China’s Foreign Affairs Minister Qin Gang (秦刚) in March of 2023. During his address at the Two Sessions, Qin highlighted how foreign media commonly use the term ‘wolf warrior diplomacy’ to describe Chinese foreign relations. Qin argued that this term has become a “discourse trap.” By this, he meant that the phrase has been so deeply embedded in Western discussions about China’s foreign policy that it hinders genuine understanding of the actual dynamics. Qin implied that, contrary to perceptions, Chinese diplomats are the ones who are actually ‘dancing with wolves’ while navigating complex international relations. Interestingly, later in 2023, Qin Gang was suddenly replaced in his role by Wang Yi, the CCP’s most senior foreign affairs official. No official explanation was provided for this unexpected change.

#7: CAO CAO FLIPS THE RICE BOWL

Cáo Cāo Gài Fàn (曹操盖饭)

A viral meme originating from the Chinese TV series Three Kingdoms (三国) gained significant traction on Chinese social media in 2023. In a memorable scene from the 2010 series, Cao Cao, a prominent warlord in Chinese history played by actor Chen Jianbin (陈建斌), angrily flips his rice bowl upon receiving news of a surprise attack, only to gather the spilled rice back into the bowl later. This scene featuring an enraged Cao Cao has resurfaced and struck a chord with individuals reluctantly facing reality. Turning into a popular meme, ‘Cao Cao flipping the rice bowl’ (曹操盖饭) became widely employed to convey sentiments of self-inflicted humiliation or the hesitation to undertake certain actions. Read more here.

#8: REVIVE CHINA BIDEN

Bài Zhèn Huá (拜振华) – “Revive China Biden”

While delivering a speech to the Canadian parliament in March of 2023, U.S. President Biden accidentally said he “applauded China for stepping up.” He then quickly corrected himself and saying he meant to say ‘Canada’ instead of ‘China.’ Because of this slip of the tongue, many Chinese netizens joked that Biden secretly supports China. They referred to him by the nickname “Revive the Country Biden” (Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华), also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname already circulated online since 2020 and matches with one that was previously given to former President Trump, namely that of “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国). The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and saying things that actually make China stronger (read more).

#9: CYBER YINAO

Sàibó Yīnào (赛博医闹)

Yinao (医闹) refers to the social problem of patient-doctor violence and other outbursts of anger against medical staff. A video showing a woman attacking a service robot in a local hospital went viral on Chinese social media and beyond in April of 2023. The incident reportedly took place at a Xuzhou Medical University hospital in Jiangsu, where an angry woman got so frustrated that she started swinging at the robot with a bat. Some netizens called this a form of ‘Cyber Yinao’ (Sàibó Yīnào 赛博医闹). With smart robots becoming a more important part of China’s service industry, from banks to hospitals, we might come across this term more often in the future when patients and their families lash out against the robotic staff members in the medical field.

#10: FULL TIME SONS AND DAUGHTERS

Quán Zhí Ér Nǚ (全职儿女)

In 2023, Chinese media outlet Toutiao News (头条新闻) featured the story of Nian An, a young woman who quit her job without securing a new one (also called “naked resignation” luǒcí 裸辞), and who made the decision to temporarily rely on her parents for support. She spent every weekend at her parents’ house, assisting her mother with dinner preparations and providing companionship. In return for her presence, her parents offer her a monthly allowance of 4000 yuan ($570), with the option to request additional funds if needed. Nian An viewed being a “full-time daughter” as a “freelance job full of love” (“充满爱的自由职业”). Nian An’s story led to online discussions about being a “full-time child” (全职儿女), which is different from “living off parents” (啃老). Being a “full-time child” is a transitional stage that allows young people to prepare for graduate school or switching jobs while exchanging their caretaking efforts for financial support from their parents.

#11: SECOND POSITIVE

Èr Yáng (二阳)

This buzzword directly translates as “second positive” and was at the top of China’s social media trending lists over the last summer or late spring, when the country was facing a second major Covid wave. The character 二 èr means two or second. The character 阳 yáng means [to test] positive, and is used in the context of testing positive for Covid-19. The meaning of the phrase is “to get COVID for a second time” as many people in China got infected for the second time in the summer of 2023, after most people got their first infection in late 2022.

#12: WHITE PEOPLE FOOD

Báirén Fàn (白人饭)

This year, the topic of “white people food” went viral on China’s Little Red Book (Xiaohongshu) app and beyond. The phenomenon stems from Chinese observations of typical white foreigners’ lunches, often comprising raw veggies, boiled eggs, chicken breast, processed meats, and fruits or juices. In contrast, traditional Chinese meals emphasize warm dishes paired with rice or noodles. “White people food” is commonly characterized by its simple ingredients, straightforward preparation methods, and perceived lack of flavor. Some Chinese netizens try out “white people food” out of curiosity, considering eating raw celery or baby carrots as a novel “challenge.” Others choose it because they are willing to trade the taste of food for the convenience of buying ingredients and preparing meals quickly. One user on Xiaohongshu shared, “After reaching the stage where I eat only for survival, I’ve started to appreciate ‘white people food’ because I can prepare it very quickly” (read more here).

#13: RESIGNATION CEREMONY

Lízhí Shèngdiǎn (离职盛典)

Hooray, I quit my job! The phenomenon of the “Resignation Ceremony” (lízhí shèngdiǎn 离职盛典 ) emerged as a trend in 2023 where young individuals go to great lengths to celebrate their departure from a job with banners and hotpot dinners. With job security declining, quitting one’s job has become more common in today’s China. This increased frequency has made something that was previously considered somewhat embarrassing more acceptable and natural. Moreover, the prevalence of China’s intense ‘996 work culture’ has fueled the desire among young people to quit their jobs. As a result, the process of resignation has transformed from a secretive and silent departure into a joyous occasion comparable to receiving a promotion.

#14: SMALL TOWN UPPER CLASS LADIES

Xiǎozhèn Guìfù (小镇贵妇)

The phenomenon of the “small-town elites” has been popping up more frequently in Chinese online media and on lifestyle app Xiaohongshu throughout 2023. The term “small town upper class ladies” (小镇贵妇) refers to women who reside in small towns and are leading comfortable lives close to their hometowns. They do not need to rush to work early in the morning, don’t struggle with hard jobs, and earn a comfortable living, seemingly without the stresses of urban life. They are envied by urban dwellers, not only because of their financial stability – often thanks to their affluent families – but also because of the free time they have to engage in various activities, such as decorating their homes or doing yoga.

#15: PURE IDOLS

Nèiyú Chúnyuán (内娱纯元)

They are the ones who are staying “pure” in times of scandal. The “Chunyuan of the entertainment industry” refers to idols in Mainland China who are regarded as flawless and worthy of admiration. The term “内娱” (nèiyú) is a shortened form of “内地娱乐圈” (nèidì yúlèquān), which means the Mainland entertainment industry. Meanwhile, “纯元” (chúnyuán), meaning ‘pure essence,’ symbolizes individuals seen as pure and perfect. In light of the numerous scandals involving idols in mainland China in recent years, including prominent stars like Fan Bingbing (范冰冰), Kris Wu (吴亦凡), or Cai Xukun (蔡徐坤), discussions have emerged around identifying figures who remain untainted by controversy and are still deserving of being cherished as flawless role models.

#16: CALLING A RAT A DUCK

Zhǐ Shǔ Wéi Yā (指鼠为鸭)

There is a famous Chinese idiom, zhǐ lù wéi mǎ 指鹿为马, that translates to “calling a deer a horse” (or “calling a stag a horse”), meaning to misrepresent something. The phrase comes from a story about the corrupt eunuch and minister Zhao Gao (赵高) during the Qin Dynasty who brought a deer to the second emperor, presenting it as a “horse.” Fearful to disagree with him, many people followed him and also identified the animal as a horse. In June of 2023, a student found a rat head – teeth and all – inside his school canteen meal and posted about it on social media. As the incident blew up, the school refused to admit any wrongdoing and argued that the student was mistaken, insisting that it was actually duck he found. Reflecting on this peculiar incident (read), the idiom has evolved, with people coining the phrase “calling a rat a duck” (zhǐ shǔ wéi yā 指鼠为鸭) to capture the absurdity of the situation.

#17: THE UNKILLABLE SHIJIAZHUANG GUY

Shābùsǐ de Shíjiāzhuāngrén (杀不死的石家庄人)

Shijiazhuang is the capital and most populous city of China’s Hebei Province which has been attempting to rebrand itself as China’s rock ‘n’ roll capital to boost tourism and its local economy. As part of this revamping, the phrase “The Unkillable One from Shijiazhuang” (杀不死的石家庄人) has become a popular term on Chinese social media. Shijiazhuang used “The Unkillable Shijiazhuang” as its slogan to spread positivity, but netizens primarily used it sarcastically. It comes from a song released by the Hebei Communist Youth League in 2022, which serves as a ‘harmonious’ reinterpretation of the renowned 2010 Chinese song “Kill the One from Shijiazhuang” (杀死那个石家庄人) by the Chinese rock band Omnipotent Youth Society. The original song, which delved into the turbulence stemming from widespread job losses, deeply resonated with Chinese youth. The reworked song title and its association with Shijiazhuang’s rebranding as a “Rock N Roll center” led to humorous adaptations online, partly poking fun at the Communist Youth League’s attempt to revise a song that once conveyed hardship into one echoing state propaganda, and showcasing a form of self-deprecating expression among netizens.

#18: ANTI RADIATION

Fáng Fúshè (防辐射)

Since Japan began releasing treated radioactive water from the damaged Fukushima power plant into the ocean, various related discussions surged across Chinese social media platforms, making it one of the biggest trending topics of the year. In light of worries over contaminated water, concerned netizens started to actively seeking ways to safeguard themselves against potential radiation risks. The term “anti-radiation” therefore gained significant popularity online and some businesses attempted to profit from these radiation concerns. One Japanese-style restaurant in Shanghai even offered an “anti-radiation” set meal (“防辐射”套餐).

#19: HUAXI COINS

Huāxī bì (花西币)

It was one of the biggest controversies in 2023: China’s most famous beauty influencer Li Jiaqi (Lipstick King) suddenly lashed out against a viewer who questioned the price of an eyeliner he was selling during a livestream. Li was promoting Chinese make-up brand Florasis, which is known as Huāxīzǐ (花西子) in China, and some viewers thought 79 yuan ($11) was a bit expensive for a pencil, after which Li rolled his eyes and snapped that viewers should instead ask themselves if they had worked hard enough to deserve a raise. Him saying “what do you mean, expensive?” (“哪里贵了”) instantly became a meme-worthy phrase. The incident sparked a series of memes and discussions, and among them the question of what one can buy with 79 yuan in China today was a big one. While some suggested they could feed an entire family for one day with that money, others said that it would buy their office lunches for a week. This humorous situation gave rise to the term ‘Huaxi Coins’ or ‘Floracash’ (花西币), with netizens playfully using the eyebrow pencil’s price as a new currency unit, where one Huaxi Coin equals 79 yuan. People even started jokingly expressing their earnings in Huaxi Coins, and some proudly mentioned the cost of snacks or meals, saying things like ‘it only cost me a quarter in Floracash for three’ or ‘tonight’s dinner was just half a Huaxi Coin!'”

#20: FAR AHEAD

Yáo Yáo Lǐng Xiān (遥遥领先)

During the much-anticipated Huawei launch event in September of 2023, consumer chief Richard Yu unveiled an impressive array of Huawei’s latest products and innovations, such as the latest version of its MatePad Pro (the world’s lightest and thinnest tablet of its kind), a new smart TV, wireless earphones, and he also announced Huawei’s first sedan, the Luxeed S7, promising it would be “superior” to Tesla’s Model S “in every specification.” During his speech, Yu recurringly used the phrase “far ahead”, “遥遥领先” (yáo yáo lǐng xiān), to indicate that Huawei is fully future-proof and far ahead of other companies. As a result, the phrase became popular among Chinese netizens, who started using it for all kinds of things. It did not take long for the phrase to get registered as a trademark by some business owners in Shenzhen who hope it might bring them some profit.

#21: SPECIAL FORCES TRAVEL

Tèzhǒngbīngshì Lǚyóu (特种兵式旅游)

Fun, fast, frugal travel was all the rage in this ‘post-lockdown’ year. As people could go out to travel again, so-called ‘special forces travelers’ flooded popular tourist spots across China. Their mission: covering as many places as possible at the lowest cost and within a limited time frame. On social media, young travelers shared their strict schedules of arriving in a certain place and then climbing mountains in the morning, doing city tours during the day, and participating in a local cuisine cooking class at night before taking off again and save on hotel money by taking a night bus to the next destination. While the travel trend became a social media hype, there were also those criticizing the trend for being superficial.

#22: REVERSE CONSUMPTION

Fǎnxiàng Xiāofèi (反向消费)

This year, especially during the online shopping festival season, the concept of Chinese consumers engaging in ‘reverse spending’ or ‘reverse consumption’ – also known as ‘rational consumption,’ – became a hot topic. ‘Reverse consumption’ is a recent trend that is especially popular among Chinese young people, and that is all about pursuing sustainable and cost-effective products instead of focusing on consuming for the sake of buying brands or spending money. The trend does not necessarily suggest a focus on cheap products, but rather a refusal to celebrate consumerism and overpay for products that lack value for the price. Some Weibo users view this trend as a reaction to the constant shopping festivals and the pressure on young people to keep buying more in the thriving Chinese e-commerce market, leading to increased luxury consumption. As consumer attitudes gradually begin to change, young people no longer simply believe that “expensive means good,” and are now being more rational in their shopping behavior that is more about ‘value for money.’

#23: TOXIC FANGIRLING

Rǔmàshì Zhuīxīng (辱骂式追星)

In China’s ever-evolving fan culture, the phenomenon of ‘rǔmà shì zhuīxīng‘ (辱骂式追星, lit: ‘abusive-style celebrity admiration’) or ‘toxically fangirling’ has become a trend this year. This term refers to a rather extreme way for fans to engage with their their idols. When pleased, they express intense love and support for their idols, but they can turn into abusive trolls targeting their idols when dissatisfied. This shift from love to aggression can be triggered by small things, like an unflattering photo or an unsatisfactory performance. Initially viewed as a departure from blind loyalty, this fan behavior has now turned somewhat toxic. Netizens interpret this ‘toxic fangirling’ phenomenon half ironically, half seriously, suggesting its origin may be rooted in the collective childhood trauma of Chinese fangirls.

#24: SUBJECT THREE DANCE

Kēmù Sān Tiàowǔ (科目三跳舞)

‘Subject Three’ has become a buzzword on Chinese social media in 2023 in connection with a viral dance, the Subject Three Dance (科目三舞蹈). From Douyin to Bilibili, the dance is super popular online and is performed by various people, from online influencers to virtual vloggers. The dance has become especially big since the renowned Chinese hotpot chain Haidilao allowed its staff to perform this viral dance for diners upon request, leading to amusing and occasionally awkward situations. The term ‘Subject Three’ allegedly first gained traction in 2022 or early 2023 following a video showcasing the jubilant atmosphere of a Guangxi wedding. Subsequently, ‘Guangxi Subject Three’ (广西科目三) became a popular joke. Although traditionally associated with the third part of a driver’s license exam, people playfully suggested that Guangxi locals undergo three significant “exams” in their lifetime: one for singing folk songs, one for mastering the art of slurping rice noodles, and the third for dancing (“广西人一生中会经历三场考试,科目一唱山歌,科目二嗦米粉,科目三跳舞”). By now, the dance has transcended its original context of Guangxi weddings and Haidilao staff dances, as it’s turned into a true social media hype where people create and share videos of themselves and others performing the Subject Three Dance, which is characterized by playful and exaggerated movements accompanied by the background music of “江湖一笑” (Jianghu Smile), making it entertaining, humorous, and, most of all, meme-worthy. .

#25: RAT-LIKE HANDSOME

Shǔxì Shuàigē (鼠系帅哥)

The term “Rat-Type Handsome Guy” (鼠系帅哥) has actually been around for some time, but attracted more attention on Chinese social media recently. The word is part of a group of other terms to describe popular aesthetics of famous men with features resembling animals. In 2022, for example, the “Monkey-Type Handsomes” (猴系帅哥) were especially popular. The term was used to describe the kind of Chinese celebrities who were undeniably handsome and also showed some resemblance to monkeys due to their strong brow ridges, narrow and long face, thin upper lip, and prominent T-zone. When categorizing handsome men in China’s entertainment industry into animal-types, from monkeys to snakes, from dogs to birds, it is not always only about facial features but also about a certain air or vibe (氛围感) that surrounds an idol. A loyal and cute dog-like vibe, a calm and strong ox-like feeling, or a sharp and sexy cat-like character. This year, the ‘rat-like’ handsome men have been more in vogue. They have small eyes, a pointed jaw and a small mouth. Although not all actors who are rat-like are deemed handsome, those that are handsome are all the more rare – and popular.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Ruixin Zhang, Zilan Qian, and Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Memes & Viral

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Throughout the years, Biden has received many nicknames on Chinese social media.

Published

4 days agoon

July 22, 2024

Our Weibo phrase of the week is Bye Bye Biden (bài bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登). As news of Biden dropping out of the presidential race went viral on Weibo early Monday local time, it’s time to reflect on some of the popular nicknames and phrases given to US President Joe Biden on Chinese social media.

🔹 Biden in Chinese: Bàidēng 拜登

Biden in Chinese is generally written pronounced and written as Bàidēng 拜登. Although the character 拜 (bài) means “to pay respect, to worship” and 登 (dēng) means “to ascend, to climb,” they’re used here primarily for their phonetic similarity. The characters chosen are neutral to avoid any negative implications in the official translation of Biden’s name.

Why are non-Chinese names translated into Chinese at all? With English and Chinese being vastly different languages with entirely different phonetics and scripts, most Chinese people find it difficult to pronounce a foreign name written in English. Writing foreign names in Chinese not only standardizes them but also makes pronunciation and memorization easier for Chinese speakers.

🔹 Bye Biden: Bài Bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登

Because Biden is Bàidēng, and the Chinese for ‘bye bye’ is written as bài bài 拜拜, some netizens quickly created the wordplay “bài bài Bàidēng” 拜拜拜登 (“bye bye Biden”) upon hearing that Biden would not seek reelection. Try saying it out loud—it almost sounds like you’re stammering.

🔹 Old Joe: Lǎo Dēng Dēng 老登登

Another common farewell greeting to Biden seen online is “bài bài lǎo dēng dēng” 拜拜老登登, which sounds cute due to the repetition of sounds.

“Old Biden” or “lǎo dēng dēng” 老登登 is a common online nickname for Biden in Chinese. The reduplication of the 登 (dēng) makes it sound playful and affectionate, while the “old” prefix is commonly used when referring to someone older. It’s similar to calling someone “Old Joe” in English.

🔹 Biden Variations: 拜灯, 白等, 败蹬

Let’s look at some other ways Biden is nicknamed online:

Besides the official way of writing Biden with the 拜登 Bàidēng characters, there are also other variations:

拜灯: bài dēng

白等: bái děng

败蹬: bài dèng

These alternative ways of writing Biden’s name are not neutral. Although the first variation is not necessarily negative (using the formal Biden 拜 bài character but with ‘Light’ 灯 dēng instead of the other 登 ‘dēng’), the other two variations are usually used in more negative contexts.

In 白等 (bái děng), the first character 白 (bái) means “white,” which can evoke associations with old age due to white hair (白发). The character 等 (děng) means “to wait,” and the combination can imply being old and sluggish.

败蹬 (bài dèng) is typically used by netizens to reflect negative sentiments towards the American president. The characters separately mean 败 (bài): “to be defeated,” “to fail,” and 蹬 (dèng): “to step on,” “to kick.” This would never be used by official media and is also often used by netizens to circumvent censorship around a Biden-related topic.

🔹 Revive the Country Biden: Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华

Then there is 拜振华 Bài Zhènhuá: revive the country Biden

In recent years, Biden has come to be referred to with the Chinese nickname “Revive the Country Biden,” also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname has circulated online since 2020 and matches one previously given to former President Trump, namely “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国).

The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are seen as benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and dealing with China.

🔹 Sleepy King: Shuì wáng 睡王

Shuì wáng 睡王, Sleepy King, is another common nickname, similar to the English “Sleepy Joe.” During and after the 2020 American presidential elections, there were numerous discussions on Chinese social media about ‘Trump versus Biden.’ Many saw it as a contest between the ‘King of Knowing’ (懂王) and the ‘Sleepy King’ (睡王).

These nicknames were attributed to Trump, who frequently boasted about his unparalleled understanding of various matters, and Biden, who gained notoriety for being older and tired. Viral videos, some manipulated, showed him nodding off or seemingly disoriented. The name ‘Sleepy King’ then stuck.

🔹 Grandpa Biden: Bài Yéyé 拜爷爷

Throughout the years, Biden has also been nicknamed Bài yéyé 拜爷爷, “Grandpa Biden.” This is usually more affectionate, though it emphasizes his age—Trump is not much younger than Biden and is not nicknamed ‘Grandpa Trump.’

Another similar nickname is lǎo bái 老白, “Old White,” referring to Biden’s age and white hair. 白 (bái, white) can also be a surname in Chinese. This nickname makes it seem like Biden is an old, familiar friend.

On Weibo, many speculate that American Vice President Kamala Harris will be the new candidate for the Democrats, especially since she’s been endorsed by Biden. Many have little confidence that she can compete against Trump. Her Chinese name is Kǎmǎlā Hālǐsī 卡玛拉·哈里斯, commonly referred to as ‘Harris’ (Hālǐsī).

In light of the latest developments, some netizens jokingly write: “Bye bye Biden, Ha ha ha, Harris.” (Bài bài, Bàidēng. Hā hā hā, Hālǐsī 拜拜,拜登。 哈哈哈,哈里斯). With a new Democratic candidate entering the presidential race, we can expect a fresh batch of creative nicknames to join the mix on Chinese social media.

Want to read more? Also read: Why Trump has Two Different Names in Chinese.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

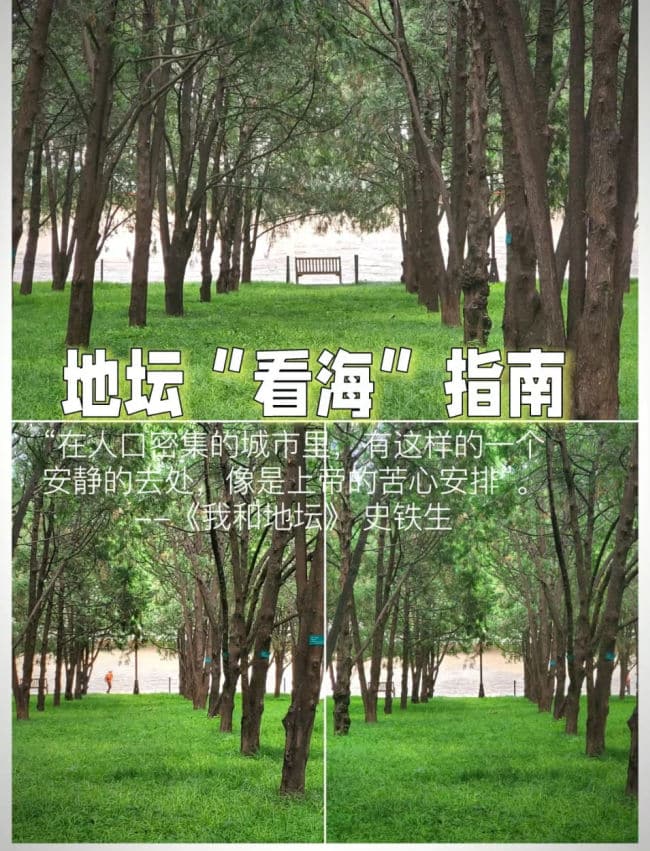

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

This “seaview” spot in Beijing’s Ditan Park has become a new ‘check-in spot’ among Chinese Xiaohongshu users and influencers.

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 15, 2024

“‘The sea in Ditan Park’ is a perfect example of how Xiaohongshu netizens use their imagination to change the world,” a recent viral post on Weibo said (“地坛的海”完全可以入选《红薯人用想象力颠覆世界》的案例合集了”).

The post included screenshots of the Xiaohongshu app where users share their snaps of the supposed seaview in Beijing’s Ditan Park (地坛公园).

Ditan, the Temple of Earth Park, is one of the city’s biggest public parks with tree-lined paths and green gardens in Beijing, not too far from the Lama Temple in Dongcheng District, within the Second Ring Road.

On lifestyle and social media platform Xiaohongshu, users have recently been sharing tips on where and how to get the best seaview in the park, finding a moment of tranquility in the hustle and bustle of Beijing city life.

Post on Xiaohongshu to get the seaview in Ditan Park.

But there is something peculiar about this trend. There is no sea in Ditan Park, nor anywhere else in Beijing, for that matter, as the city is located inland.

The ‘seaview’ trend comes from the view of one of the park’s stone walls. In the late afternoon, somewhere around 16pm, when the sun is not too bright, the light creates an optical illusion from a certain viewpoint in the park, making the wall behind the bench look like water.

You do have to capture the right light at the right moment, or else the effect is non-existent.

Some photos taken at other times of the day clearly show the brick wall, which actually doesn’t look like a sea at all.

Although the ‘seaview in Ditan’ trend is popular among many Xiaohongshu users and influencers who flock to the spot to get that perfect picture, there are also some social media commenters who criticize the trend of netizens always looking for the next “check-in spot” (打卡点).

There are also other spots popular on social media that look like impressive areas but are actually just optical illusions. Here are some examples:

One Weibo user suggested that this trend is actually not about people appreciating the beauty around them, but more about chasing the next social media hype.

The Ditan seaview trend is not entirely new. In May of this year, Beijing government already published a post about the “sea” in Ditan becoming more popular among social media users who especially came to the park for the special spot.

The Beijing Tourism Bureau previously referred to the spot as “the sea at Ditan Park that even Shi Tiesheng didn’t discover” (#在地坛拍到了史铁生都没发现的海#).

Shi Tiesheng (1951–2010) is a famous Chinese author from Beijing whose most well-known work, “Me and Ditan,” reflects on his experiences and contemplations in Ditan Park. At the age of 21, Shi Tiesheng suffered a spinal cord injury that left him paralyzed from the waist down. Ditan Park became a place for him to ponder life, time, and nature. Despite the author’s deep connection with the park, he never described seeing a “sea” in the walls.

Shi Tiesheng in Ditan Park.

If you are visiting Ditan Park and would like to check out the ‘sea’ yourself in the late afternoon, there are guides on Xiaohongshu explaining the route to the viewpoint. But it should not be too difficult to find this summer—just follow the crowds.

By Manya Koetse and Ruixin Zhang

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?