Featured

Weibo Watch: Bad Manners

A string of violent incidents made people wonder what else is brewing at Manner Coffee besides fresh coffee.

Published

4 months agoon

PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #31

This week’s newsletter:

◼︎ 1. Editor’s Note – Bad manners

◼︎ 2. What’s New and Noteworthy – A closer look at the featured stories

◼︎ 3. What’s Trending – Hot highlights

◼︎ 4. What’s Remarkable – AI Against AI

◼︎ 6. What’s Popular – Fu Bao, the Commercial Gem

◼︎ 7. What’s Memorable – Lying Flat

◼︎ 8. Weibo Word of the Week – “Very Tougan”

Dear Reader,

On the morning of June 17, a Shanghai barista lost his temper when an impatient female customer kept nagging him about her coffee at a small coffee shop at Pudong’s Meihua Road. After she had asked him for his name and then held up a phone in his face to record him, he snatched the phone from her hands and started scolding her.

As the woman continued to rant, the situation escalated quickly. The young man stepped out to the other side of the counter to confront her, which soon turned into a physical altercation. After the woman kicked him, the man slapped her in the face and even threw a few punches (video link).

The incident occurred at Manner Coffee, a Chinese chain known for its affordable, high-quality takeout coffee. The altercation, captured on security video and going viral on Chinese social media, was not the only major incident at Manner Coffee that day.

On the same day, a female barista at another Manner Coffee at Shanghai’s Weihai Road also lost her temper while dealing with a complaint about slow service, after which she threw coffee grounds at the customer (video link).

As both incidents quickly went viral, a third incident came to light, in which a barista and a customer got into a fight behind the service counter at a Manner Coffee in Shanghai’s Haimeng Yifang mall (video link). Unsurprisingly, the string of incidents made people wonder what else was brewing at Manner Coffee besides fresh coffee.

A Coffee Company “Filled with Emotion”

If you’re based in Shanghai, you might be familiar with Manner Coffee, but it is not as well-known nationwide as Chinese coffee chains like Luckin or Cotti Coffee.

Manner was established in Shanghai in 2015 by coffee enthusiast Han Yulong (韩玉龙), who had a clear vision for the company. Rather than focusing on novel drinks and quick trends, he wanted to offer classic, affordable coffee to go.

As part of offering this kind of high-quality espresso and other coffee drinks, Han insisted that Manner would not use fully automated machines, like Luckin or Starbucks, but that the baristas would work with traditional semi-automatic machines that would require more input from the staff.

“This should be a business filled with emotion” (“有感情的行业”), Han explained, stressing his aspiration to create a “pure coffee shop” (“做一家纯粹的咖啡店”).

In just six years, Han Yulong expanded the Manner Coffee brand to 194 stores nationwide. Now, Manner has opened its 1,000th store, and Han has been included in the list of the top 1,000 richest people in China.

Although the concept behind Manner Coffee is commendable, the recent incidents have shown that Han Yulong has indeed created a business “filled with emotion,” but in all the wrong ways. What were supposed to be good Manner shops have led to bad manners from burned-out staff and impatient customers.

This article [in Chinese] by Huxiu explains how Manner’s baristas sometimes need half an hour to properly set up the coffee machines before their actual work begins.

In many shops, the baristas are furthermore single-handedly responsible for taking orders, handling payments, printing and sticking labels, making coffee, and cleaning.

Manner’s staffing is based on store sales: stores with daily sales below 5,000 RMB ($688) reportedly have only one employee, while those exceeding 6,000 RMB ($826) have two.

This raises questions on the maximum workload one barista can actually handle in a shift.

If it is true that it would take about six minutes per cup to maintain service and quality, then one barista would already be incredibly busy just making 80-100 cups in one shift. But with coffee prices around 20 RMB ($2.75), a daily sales target of 2,500 RMB would mean preparing approximately 120 cups of coffee.

No wonder that Chinese media interviews with Manner employees revealed significant stress and pressure within the company’s work environment.

Coffee Involution

There are various ways to interpret the recent outbursts at different Manner Coffee shops. In the first incident, where a young male barista slapped a female customer, one might expect widespread condemnation of such male-to-female violence, support for the customer, and discussions about gender-based violence. However, most social media users appear to be siding with the baristas, largely due to how the situation is being contextualized in online discussions. These incidents have opened the floodgates to stories about the immense pressure faced by Manner baristas and the unfair working conditions they endure.

After Manner Coffee issued a public apology for the incidents and promised to do everything possible to prevent such events in the future, the public turned against the company. Critics accused Manner of exploiting its employees, who work tirelessly to earn around 5,000 RMB ($688) per month, while founder Han Yulong has ascended to become one of the wealthiest people in China.

The word that keeps popping up in this context is “involution”, nèijuǎn 内卷. This term, which has become a Chinese buzzword over the past four years, is used to describe the ‘abnormal normal state’ of an ongoing rat-race in the Chinese education and employment market, leaving young people feeling overworked and run down as they try to keep up with the standards set by their peers who appear to be even more hardworking.

As I’ve previously described in my article here, the term ‘involution’ and how it is used today comes from a work by American anthropologist Clifford Geertz titled Agricultural Involution – The Processes of Ecological Change in Indonesia (1963). In this work, Geertz explores the agricultural dynamics in Indonesia during the colonial period’s Cultivation System, where a radical economic dualism existed within the country: a foreign, Dutch economy and a native, Indonesian economy (p. 61-62).

The term ‘involution’ comes from this book by Geertz, published in 1963.

Geertz describes how the Javanese faced a deepening demographic dilemma as they saw a rapidly growing population but a static economy, while the Dutch, who organized Javanese land and labor, were only growing in wealth (69-70). Agricultural involution is the “ultimately self-defeating process” that emerged in Indonesia when the ever-growing population was absorbed in high labor-intensive wet-rice cultivation without any changing patterns and without any progress (80-81).

But how do we make the jump from Geertz to Manner?

The term ‘involution’ often comes up together with criticism of China’s ‘996’ work system (working from 9am-9pm, 6 days a week). Although Alibaba founder Jack Ma once called the 12-hour working day a “blessing,” the system is controversial, with many condemning how Chinese (tech) companies are exploiting their employees, who are caught in a conundrum; they might lose their sanity working such long hours, and might lose their job and future career prospects if they refuse to do so.

The term is also used to describe the complexities that come with the extreme pursuit of high-quality and low prices that is ubiquitous in the Chinese market.

‘Involution’ is happening at Manner Coffee in two ways. Top-down, you see how China’s coffee market has become increasingly competitive while operating costs are rising. Facing financial pressures, coffee chains such as Manner are saving on staff and store size but at the same time are driving up sales while keeping their coffee prices low to compete with Starbucks, Luckin, and other big chains. It’s what this 36kr article calls “suicidal pricing” (“自杀式”定价).

Bottom-up, this results in overwhelmed employees who are working hard to keep their jobs by maintaining an unrealistic standard of making hundreds of cups of coffee during their shifts – after all, their colleagues do it, so they must keep up with a standard set too high without anyone really profiting from it, leading to mental breakdowns and conflicts with impatient customers.

Instead of condemning Manner workers who lash out against customers, many people empathize with them as a way to voice their own concerns about work environments and employee welfare.

Rather than punishing its employees, many argue that Manner should radically change its management practices.

Others say that while Manner’s original concept of aiming for high-quality coffee is admirable, good coffee is not just in the coffee beans but also in how employees are treated. Chinese economist blogger and author Yu Fenghui (余丰慧) calls the turmoil surrounding Manner Coffee a “wake-up call for the entire industry,” arguing that a company’s true quality goes beyond its product but is reflected in social responsibility. Only in this way, he says, can a brand in this competitive market “not only run fast but also go the distance” (“不仅跑得快,而且走得远”). I guess we all like our coffee better knowing it was not made in bitterness.

Best,

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

Miranda Barnes & Ruixin Zhang contributed to this newsletter

References:

Geertz, Clifford. 1963. Agricultural Involution: The Processes of Ecological Change in Indonesia. Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.

What’s New

Americans Stabbed in China | The recent stabbing incident at Beishan Park in Jilin city, involving four American teachers, has made headlines worldwide. However, on the Chinese internet, the story was initially kept under wraps. This is a brief overview of how the incident was reported, censored, and discussed on Weibo.

What’s Trending

JUNE 13-14

Jiang Ping | The story of 17-year-old fashion design student Jiang Ping (姜萍) has become the center of online discussions. Jiang, from Jiangsu, unexpectedly placed twelfth in the preliminary round of the Alibaba Global Mathematics Competition, outperforming students from prestigious universities despite attending a vocational school often seen as inferior in China. Her talent was nurtured by her supportive teacher, Wang Runqiu (王闰秋), who helped her excel in the competition, where she was the only girl in the top 30. While many cheer Jiang on, her success has also triggered waves of criticism online, with some netizens accusing her and her tutor of cheating. The final round took place on June 22, and the results will be announced in August.

JUNE 15-17

G7 | Unsurprisingly, the G7, often accused of holding an anti-China bias, faced a wave of negative reactions on Weibo and other social media platforms in China. One viral image mocked the G7 leaders, highlighting their unpopularity in their own countries, where they are either losing votes or facing significant pressure. The image labeled the leaders as follows:

• [European Union Charles Michel]: Unelected EU official

• [German Chancellor Olaf Scholz]: Just lost elections

• [Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau]: 50-year-low poll numbers

• [French President Emmanuel Macron]: Just lost elections

• [US President Joe Biden]: Too old to stand trial

• [Japan Prime Minister Fumio Kishida]: 26% approval rating

• [UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak]: About to lose elections

• [EU Ursula von der Leyen]: Unelected EU official

The only leader not being criticized was Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

JUNE 18

618 | There have been mixed reports on this year’s June 18 “618 Shopping Festival.” Some reports claimed that sales dropped during the major shopping event, which has become nearly as well-known and hyped as the November 11 “Single’s Day” shopping extravaganza. JD.com, the company behind the 618 festival, asserted that this year’s transaction volume and orders broke records.

Chinese e-commerce and finance bloggers have discussed the matter, suggesting that the festival did not actually experience a decline. They noted that some data did not account for the different sales times across various platforms and that various measuring methods are not entirely accurate. Meanwhile, in an online shopping environment that features constant promotions, online commenters observed that there seemed to be less hype surrounding the shopping festival this year.

JUNE 19-20

Putin in North Korea | On Chinese social media, many netizens watched with interest as Putin was warmly received in North Korea. Some remarked, “Two international outcasts huddling together for warmth,” while others suggested, “Perhaps we might as well not learn English, but learn Russian and Korean instead.” Despite the unique nature of the visit, coverage of Putin’s time in Pyongyang was minimal in Chinese official media. Some bloggers noted the significance of the trip’s sequence, emphasizing that Putin prioritized his visit to China in May before traveling to North Korea.

Others focused on a small detail: when Kim Jong-un and Putin went on a ride in a luxury limo, the phone holder was holding something that was apparently deemed more important: cigarettes.

JUNE 23-24

Gaokao | The results of China’s Gaokao (National College Entrance Exams) were released and quickly became a hot topic on Chinese social media. These results are extremely important to students, as they determine which university they will be able to attend. With this crucial milestone, students now face another significant challenge: filling out college applications.

During a livestream on Sunday, renowned Chinese educational advisor Zhang Xuefeng (张雪峰) suggested that students should look beyond rankings when choosing a college. He advised that young people should also consider other aspects of the college’s location, such as the feasibility of buying a house, promising job prospects after graduation, and overall good quality of life. “Is there such a place?” one top commenter wondered.

What’s Noteworthy

A new technology to detect AI scams recently went trending on Weibo. This “AI against AI” application promises to instantly recognize whether or not a face has been ‘swapped’ through AI tech (0步破解AI换脸诈骗). This application comes at a time of intensified concerns over scams facilitated by AI.

Earlier this year, a massive AI deepfake fraud case in Hong Kong attracted widespread attention. Fraudsters tricked a worker at a multinational firm into paying them a staggering 200 million HKD ($25 million) by using deepfake technology to pose as the company’s chief financial officer in a video conference call. Last year, a similar fraud case made headlines in China after a legal representative of a technology company in Fuzhou was fooled into transferring 4.3 million yuan (about $612,000) after having a video chat with someone pretending to be his friend through AI-powered face-swapping technology.

To combat such fraud practices, this new technology can now easily analyze real-time videos on mobile, detecting flaws in the video that are invisible to the human eye to determine whether or not the person you’re talking to is real or AI-generated.

What’s Popular

Since the young panda Fu Bao (福宝) made her debut at the Sichuan panda reserve in mid-June, she has become a major topic on Chinese social media. Born and raised in a South Korean zoo, Fu Bao has captivated audiences with her charm.

Fu Bao, who has thousands of fans in South Korea, returned to China in April under panda loan agreements. Born in 2020 at South Korea’s Everland Zoo, Fu Bao is the offspring of Ai Bao (爱宝) and Le Bao (乐宝), who were sent from China in 2016 as part of the country’s “panda diplomacy.”

Under the current panda loan agreements, all cubs born abroad belong to China and must be sent back to China by around the age of four. However, Fu Bao’s return sparked controversy among South Korean fans, who started a petition to bring Fu Bao back “home” after rumors surfaced about her mistreatment in China. These rumors were refuted by Chinese authorities, who dismissed them as attempts to politicize the situation rather than genuine concern for Fu Bao’s welfare.

While fans in South Korea mourn Fu Bao’s departure, Chinese enthusiasts are happy they can finally see her, both online and offline. Whether it’s Fu Bao being livestreamed, staring through a window, or eating bamboo, the young panda is a social media sensation. Fu Bao’s success extends beyond panda diplomacy; she’s a commercial gem. From Fu Bao stickers to books, soft toys, power banks, keychains, and magnets, Taobao sellers are also thrilled that Fu Bao has come home to China.

What’s Memorable

For this pick from the archive, we revisit an article from 2022 about the phenomenon of ‘lying flat’, tǎng píng, which became a hot social trend in China in 2021 and has garnered much attention since. Supporters of China’s ‘lying flat’ movement say it is a form of collective emotional catharsis, but state media suggest it goes against the Chinese Dream.

Weibo Word of the Week

“Strong Stealth Vibe” | Our Weibo phrase of the week is tōugǎn hěn zhòng (偷感很重), translated as “strong stealth vibe.”

It’s that moment when you see someone you know and pretend to be busy on your phone to avoid social interaction. Or when someone takes a group picture and you’re unsure how to pose. Or when all eyes are on you and you wish for an invisible cloak.

Recently, the term “tōugǎn” (偷感) has emerged on Chinese social media. Tōugǎn (偷感) literally translates to “stealth sense” or “secret feeling,” but we can interpret it as an overall vibe of being “under-the-radar.” The phrase “tōugǎn hěn zhòng” (偷感很重) means “the stealth sense is strong,” and can be used to describe someone as being “very under-the-radar” or having “a strong stealth vibe.”

The exact origin of this term is unclear, but it likely first appeared on Xiaohongshu in response to a videoclip by the South Korean girl group Le Sserafim for their single “Easy,” where they sing and dance effortlessly with some low-key dance moves.

Tōugǎn (偷感) is used by young people to express a common feeling in their daily lives, where they prefer to go about things quietly and low-key, avoiding too much attention. They can still be smooth and effortless, but out of fear of embarrassment or judgment, they do so in a subtle and low-profile manner. They won’t flaunt their achievements, but wait for others to notice them.

Unlike earlier internet buzzwords where young people mock themselves, tōugǎn is not negative – it’s a bit tongue-in-cheek and a way for people to connect over their inner worlds that aren’t visible to others.

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed last week’s newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

Featured image: Part of the image is based on photo taken by photographer Liu Xiangcheng, depicting dozens of students sitting down at Tiananmen Square.

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

Also Read

China Memes & Viral

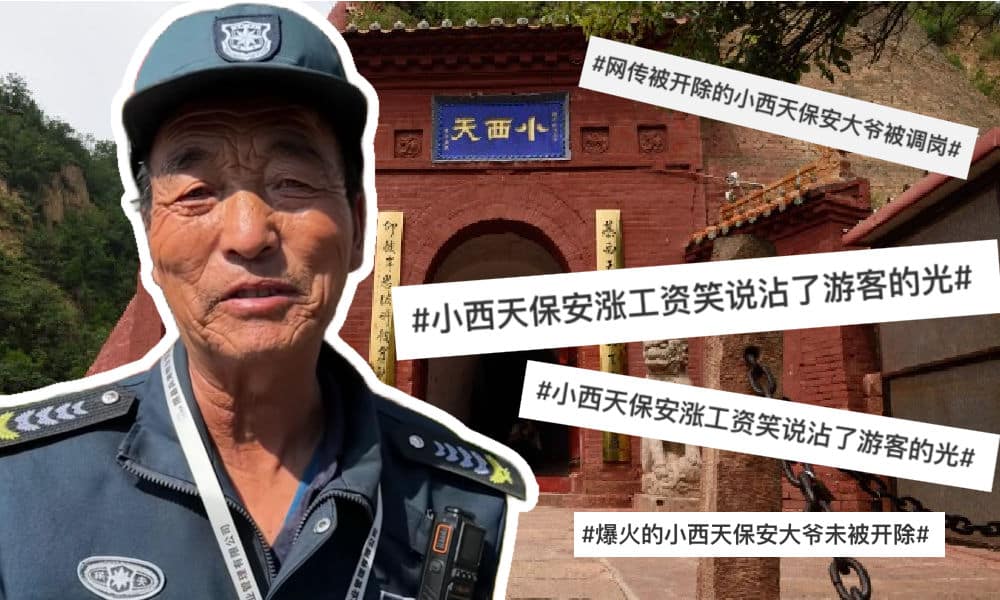

The Viral Bao’an: How a Xiaoxitian Security Guard Became Famous Over a Pay Raise

Most netizens aren’t buying the story about the Xiaoxitian bao’an allegedly “misunderstanding” his dismissal.

Published

3 days agoon

October 23, 2024

An elderly man with a friendly face from Shanxi Province’s Xi County became China’s most famous security guard this week. After first receiving a raise and then seemingly being fired from his job, the situation sparked so much discussion that it became a top trending topic on Weibo.

The man in question is a bǎo’ān (保安, security guard) at the Xiaoxitian (小西天) temple complex area in Xi County in the city of Linfen. That area has recently became a hot destination among domestic travelers because of the wildly popular video game Black Myth: Wukong. The game, inspired by the classic novel Journey to the West, features numerous real-life landmarks from Shanxi province.

As a so-called “Wukong site,” Xiaoxitian, among with dozens of other spots in Shanxi, has seen a surge in visitors, including gaming bloggers, travel vloggers, and online influencers.

One of these influencers is the Douyin vlogger “So Many Times” (@那么多曾经), who has been documenting the success of Xiaoxitian on her channel. The vlogger, who now has 12,000 fans, has been capturing the rising number of visitors to the area, especially during this year’s National Day holiday.

Her videos often focus on the best times to visit without having to queue, traffic updates, and daily visitor counts. In one video, she even captured the first group of foreign tourists visiting the area.

“They gave me a raise”

Recently, the vlogger also featured some of the security guards at Xiaoxitian, chatting with them about their local dialect, their work, and how they manage the crowds.

In the videos by “So Many Times,” the vlogger focused on one particular security guard—an elderly bao’an who was especially friendly to her. In several videos, he shared how much he enjoyed his job and the increasing responsibilities that came with Xiaoxitian’s growing popularity. He soon became affectionately known among visitors as the “Security Guard Uncle” (保安大叔).

The security guard became popular online due to videos posted by a Douyin vlogger.

In a video posted on October 15, the bao’an happily shared how grateful he was for the visitors. Smiling, he said, “I attended a meeting, and they gave me a raise. I used to earn 1,700 yuan (US$240) a month, and they added 500 yuan (US$70), so now it’s 2,100 (he meant 2,200 yuan/US$310). Everyone’s salary went up.”

The security guard suggested the tourists were to be thanked for local bao’an getting a better pay, as it increased their workload.

Uncle Bao’an tells about his 500 yuan raise.

The video quickly went viral—becoming the most-watched on the vlogger’s channel—as some viewers appreciated how ‘influencer tourism’ can benefit local workers. Others, however, were surprised by the 1,700 yuan/month (US$240) salary, considering it far too low. Beyond these discussions, the uncle’s friendly demeanor, humble enthusiasm, and obvious passion for his work touched many hearts.

A news reporter for Jimu News verified with the local citizen hotline that the minimum monthly wage in Xi County is 1,780 yuan ($250), and that the 1,700 yuan salary previously mentioned by the security guard was below this standard.

A few days later, on October 19, the Douyin vlogger whose videos made ‘Uncle Bao’an’ famous posted another short video (which has since been taken down). In this video, the security guard looked tired and said, “They [the superiors] told me not to work anymore. I didn’t say anything wrong, but they don’t want me to continue.”

He explained that his leaders thought it was inappropriate for him to appear in the other videos, though he felt it was spreading positive energy.

“These past few days, I haven’t been feeling well. They don’t want me to work, and I’m very sad.. I will never forget everyone’s support.”

“He didn’t hear it clearly”

News of the popular security guard’s alleged dismissal flooded the internet, becoming one of the hottest topics on Weibo.

Many netizens were outraged, feeling that the bao’an was unfairly forced to stop doing his job. They suggested he was dismissed because he disclosed information about his pay and the recent raise.

In light of the online controversy, the local tourism authorities responded to clarify the situation on October 20.

A spokesperson from Linfen suggested that the bao’an had not heard it clearly (“他就没听清楚”), and was not dismissed at all. Instead, he was simply given a few days off and “reassigned to a less demanding role” to lighten his workload, considering his age and the fact that he had been working without a break for the past two months.

“We all heard it clearly”

On social media, most netizens aren’t buying the story about the bao’an allegedly “misunderstanding” his dismissal.

“Do they think we’re fools? Do they think we haven’t all seen the video on the 19th?” one commenter wrote.

“Ha ha ha, if this hadn’t blown up online, he would have been fired. But because it went viral, now he’s ‘transferred to another post,’” another Weibo user remarked.

“We all heard it clearly,” another blogger added.

“Okay” / “Sure” – a meme posted by netizens after hearing about the security guard allegedly “misunderstanding” his dismissal.

People suspected that the security guard was initially fired—possibly for speaking about his low income or because he was becoming a tourist attraction himself—but the decision was reversed after it sparked public outrage online. Rather than offering an apology, the authorities then claimed it was all just a misunderstanding.

In light of the controversy and worried over the bao’an’s well-being, other Douyin users visiting Xiaoxitian began searching for the popular security guard and filmed themselves finding him at a different location. In one such video, ‘Uncle Bao’an’ confirmed that his superiors had reassigned him to lighten his workload. Some viewers commented that he didn’t seem as happy as before.

However, in the latest video by “So Many Times” (@那么多曾经), the vlogger once again features her favorite bao’an. (She used a new account for this, as her original account was restricted from posting new videos). In the video, he expresses his gratitude and happiness for the overwhelming support he has received.

“I want to thank all of you online friends for your support and your concern for me. It makes me very happy. Thank you. so many people wanted to take a picture with me today. People from Henan, from Sichuan. So many people wanted to shake my hand.”

Despite the controversy, the bao’an seems quite pleased with his sudden fame. If he does end up losing his job after all, he could always launch a new career as an online influencer.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Society

Death of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

After the tragic death of young motorcyclist ‘Shigao ProMax,’ netizens criticize influencers for reckless riding in pursuit of followers and likes.

Published

3 weeks agoon

October 2, 2024

A Chinese female motorcyclist from Suzhou, known as “Shigao ProMax” (@石膏ProMax) on Douyin, tragically passed away this week following a motorcycle crash in Suzhou’s Wujiang District.

The incident occurred in the late afternoon of September 29, when the 19-year-old Shigao, whose real name was Yang Huizi (杨惠子), was a passenger on the motorcycle, with her (male) friend driving the vehicle.

As the motorcycle collided with a car emerging from a side intersection, Yang was thrown off the back, propelled several meters through the air before landing on the road. Although she was reportedly wearing a helmet, it cracked during the crash, and she sustained a severe head injury.

A video circulating on social media shows the aftermath of the accident, with the motorcycle driver lying on the road and Yang Huizi a few meters away, initially attempting to crawl before collapsing (warning for graphic content). Despite rescue efforts, she later died in the hospital. The current condition of Yang’s friend, the rider, remains unclear.

Screenshot of the scene of the accident.

Yang had nearly 80,000 fans on Douyin, where she posted her first video in December 2019. By September 2024, she had shared a total of 1,298 videos.

On Weibo, many commenters voiced concern over how the news was headlined, criticizing the emphasis on her gender in the hashtag. The hashtag “Famous Female Rider Shi Gao Dies in Traffic Accident” (#网红女骑士石膏发生车祸身亡#) garnered over 170 million views on Weibo on Tuesday. Many commenters felt the headline made it seem as if the young woman had crashed the motor herself, while she was merely a passenger.

Others, however, see this trending news as an opportunity to highlight the risky behavior of motorcyclists, who not only endanger their own lives by speeding but also jeopardize the safety of others by showing off in traffic and driving recklessly.

Especially female influencers/motorcyclists are criticized for careless driving while flaunting their looks for social media posts.

Over the past years, the death of multiple motorcycle influencers have made Chinese headlines. In 2022, a popular Douyin influencer and motorcyclist known as “Xiaoyu Loves Eating Fish” (@小鱼爱吃鱼) died in a collision after riding in the wrong lane. She was instantly killed on the spot. Xiaoyu had gained attention for her risky driving behavior, often wearing short skirts, tight leggings, or other revealing outfits instead of proper motorcycle gear.

“Xiaoyu Loves Eating Fish,” images via Tencent News

In 2023, two young girls—one 16 and the other 21—tragically lost their lives after their motorcycle crashed into a pillar. They were speeding and, apart from wearing helmets, were dressed in skirts and stockings with no additional protective gear. Both died instantly. The 16-year-old, known as An’an (安安), was a social media influencer. Her followers had previously warned her about her reckless behavior. She rode a motorcycle without a license.

An’an’s social media profile.

Within one year alone, from October 2022 to September 2023, at least seven motorcycle influencers made headlines in China after losing their lives in traffic accidents. Some bloggers blame the intense competition for online attention for these accidents, as influencers pull dangerous stunts and push the boundaries to gain more likes and followers.

Posting a video of a woman posing for a video while riding a motorcycle, the popular Weibo content creator HuangXiPao (@黄西炮) wrote: “So many female motorcycle influencers have died, yet it doesn’t stop others from still posing on the road for photos! Is this trend really that profitable?”

One commenter expresses frustration over how news about motorcycle influencers consistently reaches the top trending lists, while other serious incidents, such as the big stabbing incident that happened in Shanghai this week, seem to be kept off the hot lists. “Every time a female motorcycle influencer dies, it makes the trending lists. Meanwhile, three people are dead and 18 injured in Shanghai! Yet you’ve completely suppressed the search term (…) What is this about?!”

News about the motorcycle incident is also a reason for official channels to remind netizens about road safety. The official China Police account shared photos of the incident, stating: “Raise safety awareness and take responsibility for your life.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

The Viral Bao’an: How a Xiaoxitian Security Guard Became Famous Over a Pay Raise

The Hashtagification of Chinese Propaganda

Hidden Hotel Cameras in Shijiazhuang: Controversy and Growing Distrust

Death of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

Why the “人人人人景点人人人人” Hashtag is Trending Again on Chinese Social Media

About Wang Chuqin’s Broken Paddle at Paris 2024

“Land Rover Woman” Sparks Outrage: Qingdao Road Rage Incident Goes Viral in China

China at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media

Weibo Watch: The Land Rover Woman Controversy Explained

Stolen Bodies, Censored Headlines: Shanxi Aorui’s Human Bone Scandal

Fired After Pregnancy Announcement: Court Case Involving Pregnant Employee Sparks Online Debate

Weibo Watch: Going the Wrong Way

Team China’s 10 Most Meme-Worthy Moments at the 2024 Paris Olympics

Weibo Watch: Shaping Olympic Narratives

“No Kimonos Allowed” – Ongoing Debate on Japanese Attire in China

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music7 months ago

China Music7 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Story of Li Jun & Liang Liang: How the Challenges of an Ordinary Chinese Couple Captivated China’s Internet