China Arts & Entertainment

Top 10 of Popular Chinese Podcasts of 2019 (by What’s on Weibo)

What are Chinese podcast app users listening to? An overview.

Published

5 years agoon

By

Jialing Xie

As the podcasting industry only seems to become more thriving around the world, What’s on Weibo tunes into China’s podcast market and selects ten of the most popular Chinese podcasts for you.

Ever since it first made its entrance into the entertainment industry, the podcast – a term coined in 2004 – has kept growing in listenership in most Western countries.

The same holds true for China, where podcasts are mainly concentrated on a couple of bigger online audio streaming platforms.

What are the most ear-catching podcast streaming services in China now? While various podcast apps have been competing with each other to attract users with their trending content, Ximalaya is one of the most popular ones as it offers the widest range of content of all major podcast apps in China. The app was first launched in 2013, and has been a top-scoring app ever since.

In terms of popularity, Ximalaya (喜马拉雅) is closely followed by DragonflyFM (蜻蜓FM), LycheeFM(荔枝FM), and a series of other podcast platforms with each implementing different business models.

How do we know what’s trending on these podcast apps? Based on user clicks and other metrics, Ximalaya has its own ranking lists of popular podcasts for five major categories: classics, audiobooks,crosstalk & storytelling, news, music, and entertainment.

DragonflyFM (蜻蜓FM) and other podcast apps also have their own rankings for even more narrowly defined categories, although these rankings often feature the same ‘most popular’ podcasts as Ximalaya and other apps.

To give you an impression and an overview of the kind of podcasts that are currently most popular in China, we have made a selection of trending podcasts across various audio apps, with some notes that might be useful for those tuning into these podcasts as learners of Mandarin (all of these popular podcasts use Mandarin).

Please note that this is not an ‘official’ top 10 list, but one that is compiled by What’s on Weibo based on various popular ranking lists in different categories. Guo Degang’s crosstalk and storytelling podcast, for instance, is ranked as a number one popular podcast on both Ximalaya and Dragonfly FM, which is why it comes in highest in our list, too.

What’s on Weibo is independent and is not affiliated with any of these audio platforms or podcasts.

#1 Guo Degang: Crosstalk Collection of 21 Years (郭德纲21年相声精选)

Category: Crosstalk & Storytelling

Duration: 20-90 min/episode

About:

Guo Degang (郭德纲, Guō Dégāng) is one of the most successful crosstalk comedians in China. In 1995, he founded his own crosstalk society, Deyun Society (德云社, Dé Yún Shè), which aims to “bring crosstalk back to traditional theaters.” Guo Degang has succeeded in making the general public pay more attention to crosstalk (相声, xiàngsheng), a traditional Chinese art performance that started in the Qing Dynasty. Like many other traditional Chinese arts, crosstalk performers are expected to have had a solid foundation that is often referred to as “kung fu” (功夫, Gōngfū) before they can perform onstage. Among the many collections attempted to gather Guo Degang’s crosstalk and storytelling performance, this podcast is probably the most comprehensive attempt thus far to gather Guo’s crosstalk and storytelling – it lists Guo’s best performances throughout his nearly three-decade career.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

This podcast contains a lot of word jokes, special idioms, and cultural and historical context, making it more suitable for advanced Mandarin learners. But beginners, don’t be discouraged! Get your feet wet with Guo’s sense of humor if you like a challenge. Accent Alert: you will hear the Tianjin accent in Guo’s performance, which is also encouraged by the crosstalk & storytelling art genre.

#2 King Fafa (发发大王)

Category: Talkshow & Entertainment

Duration: 1 – 2 hr/episode

About:

This podcast provides a glimpse into Chinese society through the lens of ordinary people and their own stories. These stories range from a Chinese mother going through struggles to give birth to her child in the UK as an immigrant, to the love-and-hate relationship between Chinese youngsters and marriage brokers. Or how about Huawei employees’ personal anecdotes, or a self-made millionaire’s confession on his sudden realization of the true meaning of life? Looking beneath the surface of people’s lives with a compassionate and sometimes somewhat cynical attitude, the talk show podcast Fafa King has won over Chinese podcast listeners.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

Enrich your vocabulary and phrases bank with this daily-conversation based podcast. Suitable for medium-level Mandarin learners.

Accent Alert: you will hear mostly Beijinger accents from the two hosts.

#3 Chasing Tech, Teasing Arts (追科技撩艺术)

Category: Technology & Art / Business podcas

Duration: 30 min -1 hr/episode

About:

This Doko.com podcast allows listeners to get new perspectives on technology, art, environmental protection, and business through the voice of aspiring Chinese youths from within China and abroad. Doko.com used to be a digital marketing agency but now describes itself as a “group of people passionate about the internet, a diverse, interesting and exciting place.”

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

Doko’s podcast features interviews between the host and guests on topics mainly relating to art and technology in a semi-formal setting. Listen to learn how to discuss these topics in Mandarin. Accent Alert: you will hear the host speaking Mandarin with a slight accent and guest speakers with various accents of their origin.

#4 Let Jenny Tell You (潘吉Jenny告诉你)

Full title: Let Jenny Tell You – Learn English and Talk about America (潘吉Jenny告诉你-学英语聊美国), Link to podcast

Category: Education

Duration: 10 – 20 min/episode

About:

Let Jenny Tell You is one of the most popular podcasts around for Chinese listeners to learn English. Hosted by Jenny and Adam, the podcast offers quite rich and unique content, discussing various topics often relating to Chinese culture and news, and of course, diving deeper into the English language.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

As a language learning podcast, this podcast is actually perfect for intermediate learners of Chinese; it works both ways for Chinese-English learners as well as for English speakers who are interested in learning Mandarin. Because Adam speaks English, you always know what the podcast is about. Accent Alert: Jenny (the host) speaks fairly standard Mandarin with minor accents.

#5 Stories Across the Globe (环球故事会)

Category: Society & Culture

Duration: 20 min/episode (length differs on Podcasts App Store)

About:

A skillful narrator digs into stories behind the news, examining various topics involving cultures, history, politics, international relations. This podcast, by China’s state-owned international radio broadcaster, often comes up as a suggestion on various platforms, and also seems to be really popular because of its news-related stories.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

Well-paced speech with an intimate tone, this podcast is a good source for learning new vocabulary and improving your pronunciation if you are already an advanced learner of Mandarin. Accent Alert: the host speaks fairly standard Mandarin with a Beijing accent.

#6 Watching Dreams Station (看理想电台)

Category: Interviews & Culture

Duration: 20 – 40 min/episode

About:

A fun and informative podcast with varied content coverage, this podcast has a refreshing tone and smooth transitions between narratives and (expert) interview footage. A great source to learn more about what Chinese ‘hipsters,’ often referred to as literary and arty youth (文青, wén qīng) care about with regular mentions of social media stories.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

This podcast has relatively slow-paced speech covering various topics, which helps to make you more familiar with new vocabulary and practice how to explain things in Mandarin. Accent Alert: you will hear hosts speak fairly standard Mandarin with minor accents.

#7 Black Water Park (黑水公园)

Category: TV & Movies, Talkshow

Duration: 1 – 1.5 hr/episode

About:

Learn what’s commonly discussed among Chinese young adults about movies and TV shows through these entertaining conversations between the two good friends Ài Wén and Jīn Huā-er.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

Suitable for medium-to-advanced-level Mandarin learners; highly engaging conversations involving lots of slang and colloquial expressions.

Accent Alert: the hosts speak with recognizable Beijinger accents, so be prepared.

#8 The Sketch is Here (段子来了)

Category: Comedy

Duration: 45 min/episode

About:

With 5.426 billion user clicks on Ximalaya, this podcast featuring funny sketches is super popular and has become a household name in China’s podcast market. It offers a taste of humor appreciated by many Chinese, which is very different from what you’d get from a podcast in the West within the same category.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

Great source to learn colloquial Mandarin and funny ice-breakers, but challenging as humor is intrinsically linked with inside jokes and word play. Accent Alert: the host has what’s considered a soothing voice and speaks fairly standard Mandarin.

#9 Ruixi’s Radio (蕊希电台)

Category: Lifestyle & Bedtime

Duration: 10 min/episode

About:

One way to examine culture is to look at what people generally worry about the most. This podcast, that always starts with the soft voice of Ruixi (the host) asking listeners “Hey, are you ok today?”, focuses on a darker side of society and addresses the social and mental struggles that adults in China are facing. Ruixi’s Radio is one of those podcasts that enjoy equivalent popularity across several podcast platforms, which indicates strong branding. For many people, it’s a soothing podcast to listen just before bedtime.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

The slow-paced monologue using language easy to understand makes a great learning material for beginning learners. Accent Alert: Ruixi (the host) speaks fairly standard Mandarin with insignificant accents.

#10 Stories FM (故事FM)

Category: Stories & Bedtime

Duration: 20 – 30 min/episode

About:

Described by the New York Times as a “rarity in a media landscape full of state propaganda and escapist entertainment,” Gushi FM was launched with the idea “Your story, your voice.” As one of China’s popular audio programs, Gushi FM features stories told by ordinary Chinese of various backgrounds.

Tips if you are a Mandarin learner:

As a collection of monologues that detail stories, describe emotions, and argue ideas, this podcast suits advanced level learners. Accent Alert: in every episode, guests with speaking and telling stories in their own local dialects.

Want to understand more about podcasts in China? We’d recommend this insightful article on the Niemanlab website.

Because there are many more popular Chinese podcasts we would like to share with you, this probably will not be our only list. A follow-up list will also contain other favorites such as Two IT Uncles (两个IT大叔), BBPark (日坛公园), and One Day World ( 一天世界).

Want to recommend another Chinese podcast? Please leave a comment below this article or tweet us at @whatsonweibo, leave a message on Instagram or reach out via Facebook.

By Jialing Xie, with contributions by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Jialing is a Baruch College Business School graduate and a former student at the Beijing University of Technology. She currently works in the US-China business development industry in the San Francisco Bay Area. With a passion for literature and humanity studies, Jialing aims to deepen the general understanding of developments in contemporary China.

China Arts & Entertainment

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

“I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like listening to Alicia Keys.” Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers.

Published

2 months agoon

May 17, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Besides memes and jokes, Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers on Chinese social media.

In May, while the whole of Europe was gripped by the Eurovision Song Contest frenzy, Chinese audiences were eagerly anticipating the return of their own beloved singing competition, Singer 2024 (@湖南卫视歌手), formerly known as I Am a Singer (我是歌手).

The show, introduced from South Korea’s MBC Television and popular in China since 2013, only features professional singers who have already made a name for themselves.

Rather than watching unknown aspiring singers who are hoping to be discovered in many singing competitions, such as Sing! China, Singer 2024 gives audiences a show filled with professional and often stunning show performances by established names in the entertainment industry.

Since 2013, renowned singers from China and abroad have appeared on the show, including Chinese vocalist Tan Jing (谭晶), British pop singer Jessie J, and the late Hong Kong pop diva Coco Lee. However, no season managed to create as many waves as the 2024 season did, dominating all social media trending topics overnight.

So, what exactly happened?

COMPETING WITH FOREIGNERS

“The difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival”

In early May, the pre-show promotion of Singer 2024 was already buzzing on Chinese social media after a list of featured singers appeared on Weibo, including big names such as American singer-songwriter Bruno Mars, Korean-New Zealand singer Rosé from Blackpink, and Japanese diva LiSA.

Although Singer previously had many foreign singers on the show, this international celebrity lineup still caused a stir.

On the day of the first episode, only two foreign singers were announced to appear on the show: young Moroccan-Canadian singer Faouzia and the Grammy-nominated American singer-songwriter Chanté Moore. The other contestants were all Chinese singers who are already well-known among Chinese audiences. Because many people were unfamiliar with the two foreign singers, they joked that the winner of this season was already set in stone; surely it would be the famous Chinese singer Na Ying (那英), known for her beautiful voice.

However, that first episode surprised everyone as the two foreign singers, Faouzia and Chanté Moore, showed outstanding vocal skills. This not only startled many viewers but also made the Chinese contestants uneasy. Several experienced Chinese singers apparently were so unnerved after watching Faouzia and Chanté Moore’s performance that their voices trembled when singing.

Since the show was broadcast live – without post-production editing or autotune – audiences got to hear the actual vocal capabilities and see performers’ genuine reactions. It seemed undeniable that the foreign contestants did much better in terms of vocals and stage presence than the Chinese ones. Some online commenters even said that the gap between Chinese and foreign singers’ levels was like “the difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival” [a local Chinese music festival].

Chinese online influencer Yongkai (@陈咏开165) shared screenshots of Chanté Moore’s backstage reactions during the show. The American celebrity seemed puzzled when hearing the somewhat underwhelming performance by Chinese singer Yang Chenglin (楊丞琳), and she appeared much more positive when Na Ying sang.

This noteworthy scene, coupled with Chanté’s comments during an interview saying that she thought the Chinese production team had invited her on the show to be a judge, turned the entire show into a display of foreign singers outshining the Chinese contestants.

By the end of the first episode, Chanté Moore and Faouzia unsurprisingly ranked first and second, with Na Ying in third place.

After the show, some online commenters jokingly pointed out that Na Ying, being of Manchu descent like the rulers of China during the Qing Dynasty, showed some similarities to Empress Dowager Cixi’s defiance against Western colonizers in the way she “single-handedly took up against on foreigners” on the show.

They humorously turned Na Ying’s expressions into memes resembling Empress Dowager Cixi from an old Chinese TV show, with captions like “I want the foreigners dead” (“我要洋人死”).

Others suggested finding better Chinese singers for the show who could compete with Faouzia and Moore.

“SINGING WELL” CULTURALLY COLONIZED?

“I’m in Zibo eating BBQ, I really don’t want to listen to Alicia Keys.”

Initially, discussions about the show were light-hearted and humorous, until some netizens who couldn’t appreciate the jokes began to dampen the mood and made online discussions more serious.

Zou Xiaoying (@邹小樱), a music critic with nearly two million followers, posted on social media after the show, stating that he would have never voted for Chanté Moore or Faouzia. Not only did Zou question their vocal talent, he also wondered if the aesthetic of Chinese listeners had been influenced by Western music taste to such an extent that it has been “culturally colonized” (“文化殖民”). Meanwhile, he praised the members of Beijing rock band Second Hand Rose as “national heroes” (“民族英雄”).

He wrote:

If I had three votes for the first episode of “Singer 2024,” I’d vote for Second Hand Rose, Na Ying, and Silence Wang [note: Chinese singer-songwriter and record producer Wang Sushuang 汪苏泷]. The reason I wouldn’t vote for Chanté Moore or Faouzia is because — do they actually sing so well?

Has our definition of “singing well” perhaps been colonized? Just as our modern-day use of Chinese has little to do with our classical Chinese poems, with the foundation of modern Chinese actually being translations from the 20th century, is this also a form of ‘cultural colonization’?

You must think I’m talking nonsense again. But when I listen to Chanté Moore singing “If I Ain’t Got You,” I find it too boring. I know her singing is “good,” but this “good” has nothing to do with me. If, for Chinese listeners, Chanté Moore’s “good” is the standard, then is that what we in the music industry should be working towards? Isn’t that funny? When you open QQ Music or NetEase Cloud Music, and it recommends these songs to you every day, won’t you be convinced to practice again?

Of course, I know Chanté Moore is in good shape, very relaxed. Actually all of the Chinese singers tonight were very nervous. Yang Chenglin (杨丞琳) was nervous, Na Ying was also nervous. Even a seemingly carefree band like Second Hand Rose, if you listened to the introduction of their song, [you’ll find] they were so nervous that Yao Lan, supposedly “China’s No.1 Guitarist”, was so nervous that he hit the wrong note. It was not even a fast-paced solo (…), how nervous could he be? When everyone’s so tense, the confidence of Chanté Moore and Faouzia is indeed something that East Asia can’t match. In East-Asian [entertainment] circles, represented by China/Japan/Korea, our different cultural habits, upbringing, and ethnic characteristics have made it so that we don’t possess these kinds of singing abilities, even including our ways of emotional expression. I don’t know from which season it started with ‘Singer’ – and if it’s some kind of Catfish Effect (鲶鱼效应 ) – that they brought international singers with different cultural backgrounds into the competition. But this isn’t the Olympics, it’s not like Liu Xiang [刘翔, Chinese gold medal hurdler] is going to defeat opponents from the United States or Cuba. “I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like Alicia Keys.” (This line is not mine, I stole it from my WeChat friend).

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Anyway, no matter if they’re strong or not, I would never vote for the foreigner.

The comment about ‘I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like [listening to] Alicia Keys’ refers to the craze surrounding China’s ‘BBQ town’ Zibo. In Zibo, Chinese visitors like to sing, drink beer, and enjoy food together; it’s a simple and modest way of appreciating life and music, which contrasts with slick and smooth American or foreign styles of performing and singing.

Whether Zou’s criticism was for attention or genuine sentiment, it shifted the focus of the discussion from music to patriotism.

CHINESE SINGERS WITH MILITARISTIC UNDERTONES

“I volunteer to join the battle”

Amidst all this, some netizens, easily swayed by nationalist sentiments, began to seek help from the “national team” (国家队) of singers — musicians employed by national-level arts troupes — to “bring glory to the nation” and teach the foreigners a lesson. Some even questioned the intentions of the Singer 2024 TV show in inviting foreign singers to participate.

On May 12th, renowned Chinese singer and philanthropist Han Hong (韩红) posted on Weibo, fueling a wave of sentiment and support. In her post, Han Hong declared, “I am Chinese singer Han Hong, and I volunteer to join the battle,” tagging the production team of the TV show. Her invitation to join the battle quickly went viral.

Han Hong meme: “Who called for me?”

Han Hong has significant influence in the Chinese music industry and society as a whole. Her usual serious demeanor and avoidance of internet pop culture made netizens unsure whether she was joking or serious. Nevertheless, regardless of her intentions, a group of well-known singers began to volunteer via Weibo, emphasizing their identity as “Chinese singers” and using phrases with strong militaristic undertones like “fighting for the country” and “answering the call.”

Although many enjoyed this new wave of national pride in Chinese music and performers, some netizens criticized the trend of transforming an entertainment show into a nationalistic competition.

Film critic He Xiaoqin (何小沁) stated, “It’s okay to take the Qing-Dynasty-fighting-foreigners comparison as a joke, but taking it too seriously in today’s context is absurd.”

Others expressed fatigue with how quickly topics on Chinese internet platforms escalate to patriotic sentiments. To bring the focus back to entertainment, they turned “I volunteer to join the battle” (#我请战#) into a new internet catchphrase.

In response, the production team of Singer 2024 released a statement on Weibo, thanking all the singers for their self-recommendations. They emphasized the show’s competitive structure but clarified that “winning” is just one part of a singer’s journey..but that the love of music goes beyond all in connecting people, no matter where they’re from.

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Online reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among Chinese netizens.

Published

3 months agoon

April 18, 2024

The recent marriage announcement of the renowned Chinese calligrapher/painter Fan Zeng and Xu Meng, a Beijing TV presenter 50 years his junior, has sparked online discussions about the life and work of the esteemed Chinese artist. Some netizens think Fan lacks the integrity expected of a Chinese scholar-artist.

Recently, the marriage of a 86-year-old Chinese painter to his bride, who is half a century younger, has stirred conversations on Chinese social media.

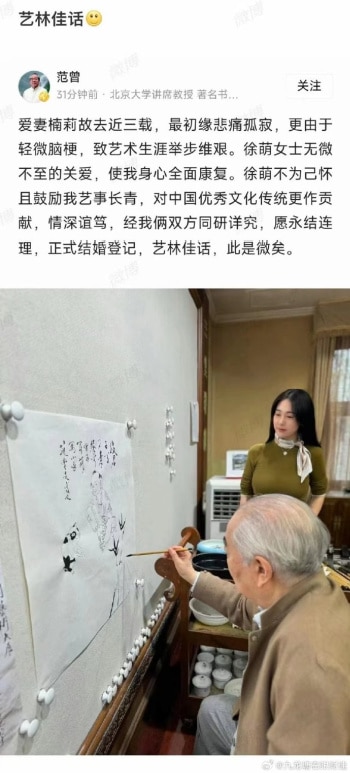

The story revolves around renowned Chinese artist, calligrapher, and scholar Fan Zeng (范曾, 1938) and his new spouse, Xu Meng (徐萌, 1988). On April 10, Fan announced their marriage through an online post accompanied by a picture.

In the picture, Fan is seen working on his announcement in calligraphic form.

Fan Zeng announces his marriage on Chinese social media.

In his writing, Zeng shares that the passing of his late wife, three years ago, left him heartbroken, and a minor stroke also hindered his work. He expresses gratitude for Xu Meng’s care, which he says led to his physical and mental recovery. Zeng concludes by expressing hope for “everlasting harmony” in their marriage.

Fan Zeng is a calligrapher and poet, but he is primarily recognized as a contemporary master of traditional Chinese painting. Growing up in a well-known literary family, his journey in art began at a young age. Fan studied under renowned mentors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, including Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Jiang Zhaohe, and Li Kuchan.

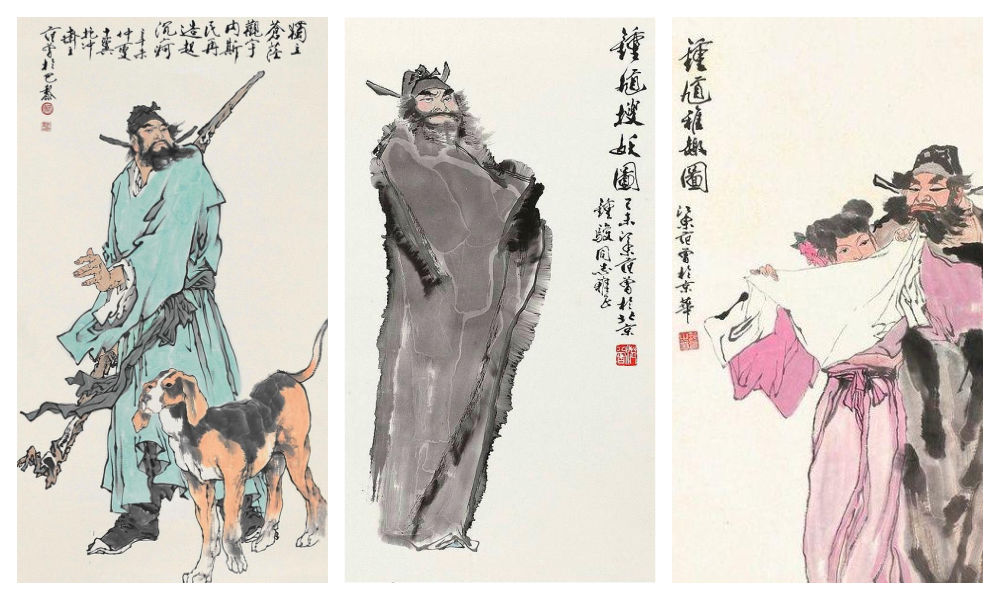

Fan gained global acclaim for his simple yet vibrant painting style. He resided in France, showcased his work in numerous exhibitions worldwide, and his pieces were auctioned at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the 1980s.[1] One of Fan’s works, depicting spirit guardian Zhong Kui (钟馗), was sold for over 6 million yuan (828,000 USD).

Zhong Kui in works by Fan Zeng.

In his later years, Fan Zeng transitioned to academia, serving as a lecturer at Nankai University in Tianjin. At the age of 63, he assumed the role of head of the Nankai University Museum of Antiquities, as well as holding various other positions from doctoral supervisor to honorary dean.

By now, Fan’s work has already become part of China’s twentieth-century art history. Renowned contemporary scholar Qian Zhongshu once remarked that Fan “excelled all in artistic quality, painting people beyond mere physicality.”

A questionable “role model”

Fan’s third wife passed away in 2021. Later, he got to know Xu Meng, a presenter at China Traffic Broadcasting. Allegedly, shortly after they met, he gifted her a Ferrari, sparking the beginning of their relationship.

A photo of Xu and her Hermes Birkin 25 bag has also been making the rounds on social media, fueling rumors that she is only in it for the money (the bag costs more than 180,000 yuan / nearly 25,000 USD).

On Weibo, reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among netizens. Despite Fan’s reputation as a prominent philanthropist, many perceive his recent marriage as yet another instance of his lack of integrity and shamelessness.

Fan Zeng and Xu Meng. Image via Weibo.

One popular blogger (@好时代见证记录者) sarcastically wrote:

“Warm congratulations to the 86-year-old renowned contemporary erudite scholar and famous calligrapher Fan Zeng, born in 1938, on his marriage to Ms Xu Meng, a 50 years younger 175cm tall woman who is claimed to be China’s number one golden ratio beauty. Mr Fan Zeng really is a role model for us middle-aged greasy men, as it makes us feel much less uncomfortable when we’re pursuing post-90s youngsters as girlfriends and gives us an extra shield! Because if contemporary Confucian scholars [like yourself] are doing this, then we, as the inheritors of Confucian culture, can surely do the same!“

Various people criticize the fact that Xu Meng is essentially just an aide to Fan, as she can often be seen helping him during his work. One commenter wrote: “Couldn’t he have just hired an assistant? There’s no need to turn them into a bed partner.”

Others think it’s strange for a supposedly scholarly man to be so superficial: “He just wants her for her body. And she just wants him for his inheritance.”

“It’s so inappropriate,” others wrote, labeling Fan as “an old bull grazing on young grass” (lǎoniú chī nèncǎo 老牛吃嫩草).

Fan is not the only well-known Chinese scholar to ‘graze on young grass.’ The famous Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), now 101 years old, also shares a 48-year age gap with his wife Weng Fen (翁帆). Fan, who is a friend of Yang’s, previously praised the love between Yang and Weng, suggesting that she kept him youthful.

Older photo posted on social media, showing Fan attending the wedding ceremony of Yang Zhenning and his 48-year-younger partner Weng Fen.

Some speculate that Fan took inspiration from Yang in marrying a significantly younger woman. Others view him as hypocritical, given his expressions of heartbreak over his previous wife’s passing, and how there’s only one true love in his lifetime, only to remarry a few years later.

Many commenters argue that Fan Zeng’s conduct doesn’t align with that of a “true Confucian scholar,” suggesting that he’s undeserving of the praise he receives.

“Mr. Wang from next door”

In online discussions surrounding Fan Zeng’s recent marriage, more reasons emerge as to why people dislike him.

Many netizens perceive him as more of a money-driven businessman rather than an idealistic artist. They label him as arrogant, critique his work, and question why his pieces sell for so much money. Some even allege that the only reason he created a calligraphy painting of his marriage announcement is to profit from it.

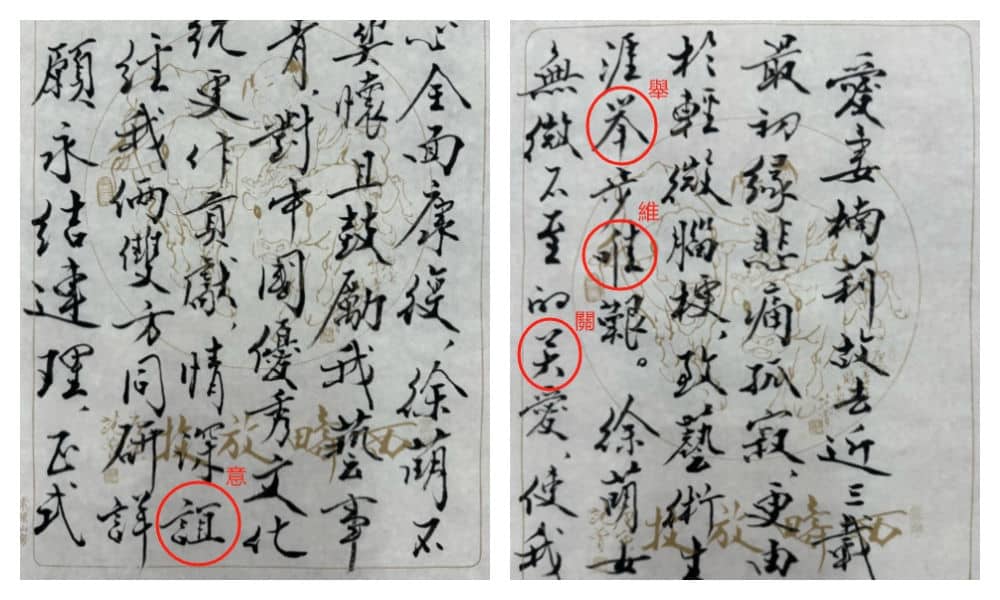

Others cast doubt on his status as a Chinese calligraphy ‘grandmaster,’ noting that his calligraphy style is not particularly impressive and may contain typos or errors. His wedding announcement calligraphy appears to blend traditional and simplified characters.

Netizens have pointed out what looks like errors or typos in Fan’s calligraphy.

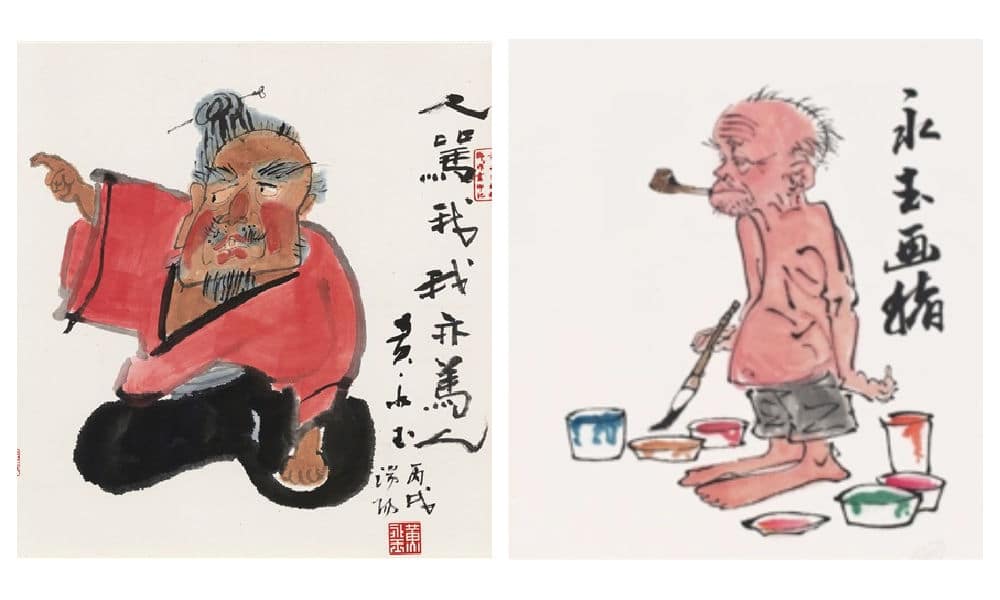

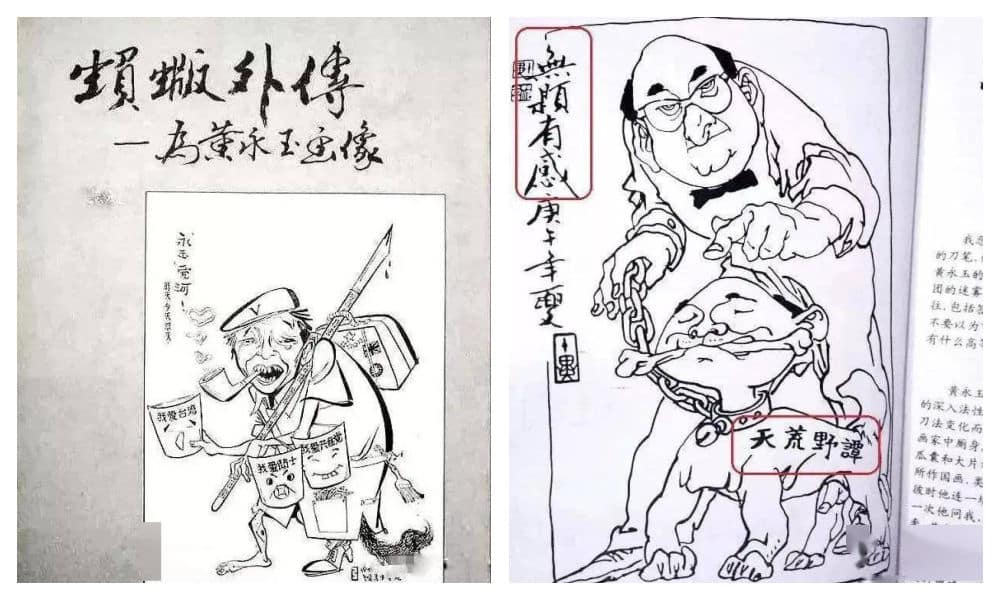

Another source of dislike stems from his history of disloyalty and his feud with another prominent Chinese painter, Huang Yongyu (黄永玉). Huang, who passed away in 2023, targeted Fan Zeng in some of his satirical paintings, including one titled “When Others Curse Me, I Also Curse Others” (“人骂我,我亦骂人”). He also painted a parrot, meant to mock Fan Zeng’s unoriginality.

Huang Yongyu made various works targeting Fan Zeng.

In retaliation, Fan produced his own works mocking Huang, sparking an infamous rivalry in the Chinese art world. The two allegedly almost had a physical fight when they ran into each other at the Beijing Hotel.

Fan Zeng mocked Huang Yongyu in some of his works.

Fan and Huang were once on good terms though, with Fan studying under Huang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Through Huang, Fan was introduced to the renowned Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文, 1902-1988), Huang’s first cousin and lifelong friend. As Shen guided Fan in his studies and connected him with influential figures in China’s cultural circles, their relationship flourished.

However, during the Cultural Revolution, when Shen was accused of being a ‘reactionary,’ Fan Zeng turned against him, even going as far as creating big-character posters to criticize his former mentor.[2] This betrayal not only severed the bond between Shen and Fan but also ended Fan’s friendship with Huang, and it is still remembered by people today.

Fan Zeng’s behavior towards another former mentor, the renowned painter Li Kuchan (李苦禪, 1899-1983), was also controversial. Once Fan gained fame, he made it clear that he no longer respected Li as his teacher. Li later referred to Fan as “a wolf in sheep’s clothes,” and apparently never forgave him. Although the exact details of their falling out remain unclear, some blame Fan for exploiting Li to further his own career.

There are also some online commenters who call Fan Zeng a “Mr Wang from next door” (隔壁老王), a term jokingly used to refer to the untrustworthy neighbor who sleeps with one’s wife. This is mostly because of the history of how Fan Zeng met his third wife.

Fan’s first wife was the Chinese female calligrapher Lin Xiu (林岫), who came from a wealthy family. During this marriage, Fan did not have to worry about money and focused on his artistic endeavours. The two had a son, but the marriage ended in divorce after a decade. Fan’s second wife was fellow painter Bian Biaohua (边宝华), with whom he had a daughter. It seems that Bian loved Fan much more than he loved her.

It is how he met his third wife that remains controversial to this day. Nan Li (楠莉), formerly named Zhang Guiyun (张桂云), was married to performer Xu Zunde (须遵德). Xu was a close friend of Fan, and helped him out when Fan was still poor and trying to get by while living in Beijing’s old city center.

Wanting to support Fan’s artistic talent, Xu let Fan Zeng stay over, supported him financially, and would invite him for meals. Little did he know that while Xu was away to work, Fan enjoyed much more than meals alone; Fan and Xu’s wife engaged in a secret decade-long affair.

When the affair was finally exposed, Xu Zunde divorced his wife. Still, they would use his house to meet and often locked him out. Three years later, Nan Li officially married Fan Zeng. Xu not only lost his wife and friend but also ended up finding his house emptied, his two sons now bearing Fan’s surname.

When Nan Li passed away in 2021, Fan Zeng published an obituary that garnered criticism. Some felt that the entire text was actually more about praising himself than focusing on the life and character of his late wife, with whom he had been married for forty years.

Fan Zeng and his four wives

An ‘old pervert’, a ‘traitor’, a ‘disgrace’—there are a lot of opinions circulating about Fan that have come up this week.

Despite the negativity, a handful of individuals maintain a positive outlook. A former colleague of Xu Meng writes: “If they genuinely like each other, age shouldn’t matter. Here’s to wishing them a joyful marriage.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Song, Yuwu. 2014. Biographical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China. United Kingdom: McFarland & Company, 76.

[2]Xu, Jilin. 2024. “Xu Jilin: Are Shen Congwen’s Tears Related to Fan Zeng?” 许纪霖:沈从文的泪与范曾有关系吗? The Paper, April 15. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_27011031. Accessed April 17, 2024.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

mamahuhu

October 30, 2019 at 6:25 pm

Just might be useful for the readers to know that Gushi FM has a wechat account that gives a scripted version of the podcast, really useful for mandarin learners.

Zhang Li

October 31, 2019 at 11:45 pm

“Story” in the Story is a podcast on the People’s Daily News app. It is very popular.

https://peoplesdaily.pdnews.cn/web/content/detail/newsf894f5268f6a468ca65638b1307ab1ad.html

Zhang Li

October 31, 2019 at 11:46 pm

https://peoplesdaily.pdnews.cn/web/content/detail/newsf894f5268f6a468ca65638b1307ab1ad.html

Adam

April 19, 2020 at 2:56 pm

Thanks for sharing, very useful for Chinese listening practice 🙂