China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese E-Readers: The Best E-book Devices in China

Overview of the top 10 e-readers in China in 2021.

Published

3 years agoon

From Onyx to Xiaomi, these are the top selling e-readers in China right now.

Ereaders have become booming business over recent years. Some people prefer an e-reader because it is easier on their eyes than reading from phone screens, others want a distraction-free digital reading style, and some just like the idea of carrying their own mini-library with them with a battery that lasts much longer than those of tablets or smartphones.

While Amazon’s Kindle is the biggest brand name in the American and European e-book reader market, the Chinese e-reader market also has several domestic brands topping the popularity lists.

Here is an overview of the top 10 brands currently dominating the lists in China. This list is based on the rankings of Zol.com, one of China’s leading IT information and business portals.

The devices mentioned in this list are all devices with E Ink (“electronic ink”) display technology, which gives them that low-power paper-like display. Devices using E Ink technology are usually in grayscale, but color e-paper technologies are now also available.

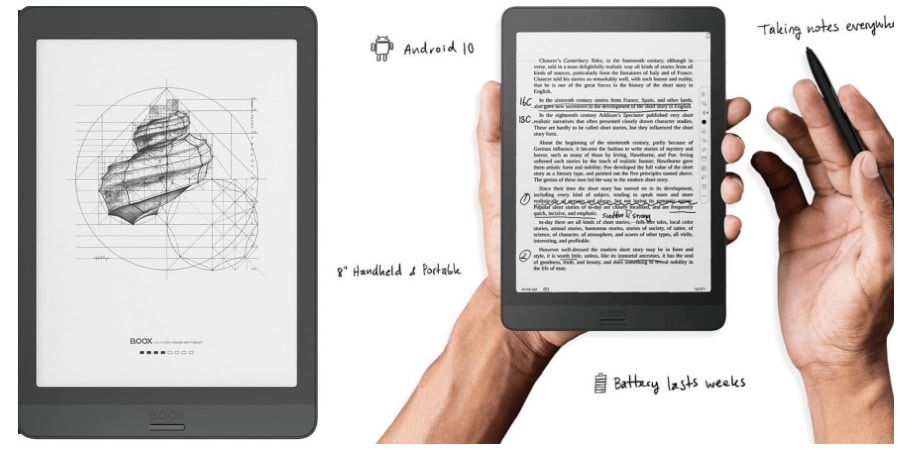

1. ONYX BOOX (CHINESE BRAND)

BOOX, also known as Onyx Boox (文石BOOX), currently is China’s top e-book reader brand, produced by Onyx International Inc., which mostly produces E Ink (ePaper) devices. Onyx Boox was founded in 2008 by a team from IBM, Google, and Microsoft. It is headquartered in Guangzhou.

What sets Onyx apart from many other e-book reader brands is that they offer devices from 7.8 to 13.3 inches that can also function as digital note-taking tablets, equipped with a pen that allows users to pen down their notes as they would in any paper notebook.

The latest Onyx devices such as the Max Lumi (13.3 inch), Onyx Boox Note Air (10.3 inch), the Note 3 (10.3 inch), and the Nova 3 and Nova 3 Color (7.8 inch) all have a wide variety of functions. Besides the common e-reading functions and digital note-taking possibilities, these devices run Android, handle many different file formats, and allow an install of Google Play, Kindle, OneDrive, and more, which really make them “like a tablet unlike any tablet” (which just happens to be their slogan).

Currently, the Boox Nova 3 is the brand’s most popular model in China. Priced at ¥2480 ($377), it is also among the pricier models in the markets due to its multifunctionality. It has 32GB of storage, E Ink Carta Plus (the latest generation of screens made by “electronic paper” technology) and also has a screen front light system, allowing users to keep on reading in the dark.

At ¥2780 ($423), the Onyx Boox Note S, which features a 9.7-inch screen, is also rising in popularity. Then there is also the Nova 3 Color 7.8-inch color E Ink tablet with a new Kaleido (Kaleido Plus) screen.

The Onyx is also sold outside of China, check it out here on Amazon.

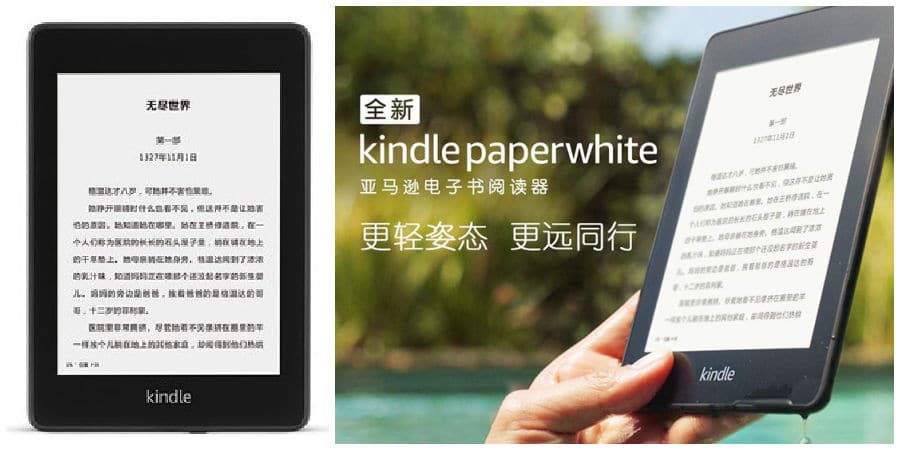

2. AMAZON

The American Amazon brand is also popular in China when it comes to its e-reader devices. While compiling this list, the Onyx and Amazon brands actually competed over the number one spot, so there is not much difference there in terms of ranking.

Along with the entry-level Kindle Migu X, the 4th generation (2018) Kindle Paperwhite (6 inches, 1448x1072px) is among the most popular e-reader models in China, priced at ¥998 ($152). Like the Onyx Nova 3, it is also available with 32GB storage, but keep in mind that the screen is smaller.

The Kindle e-book devices are much more affordable than the Onyx ones, and their functionality is more straightforward as an e-book reader. They are known for their great battery life, and since the first Kindle was introduced in 2007 it has become the world’s most famous dedicated e-reader. Kindles are designed to interface seamlessly with Amazon’s online store, which makes them perfect for Amazon fans and less appealing for those who have no desire to use the Amazon ecosystem.

The Paperwhite model has an extra advantage to it, as it allows to keep on reading while taking a bath or sitting by the pool since it is water-resistant. The Paperwhite is currently the no.2 best-sold e-book reader on Chinese major shopping platform JD. It is sold through Amazon here.

3. iFLYTEK (科大讯飞) (CHINESE BRAND)

iFlytek is a partially state-owned Chinese AI firm established in 1999 that also produces e-book readers. The company made headlines in 2019-2020 when it was blacklisted in the US for allegedly using its technology for surveillance and human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Its iFlytek Smart Office X2 (科大讯飞智能办公本X2) is the e-book reader that is currently in the top 5 list of most popular ink screen devices in China (it even scores no 1 on e-commerce platform JD.com at the time of writing), and it is also among the most expensive (¥4999/$762). The X2 is a 10.3-inch E Ink device.

Similar to the Onyx Boox devices, it is much more than an e-reader alone; it is also a note-taking device (comes with the Wacom stylus) and incorporates fingerprint authentication, Wifi/4G, (offline) voice recognition, and transcription functions; it probably is the smartest e-reader around.

The iFlytek also has a whopping 64GB storage, which can be expanded to 128GB. GizTechReview did a review of the Smart Office X2 here.

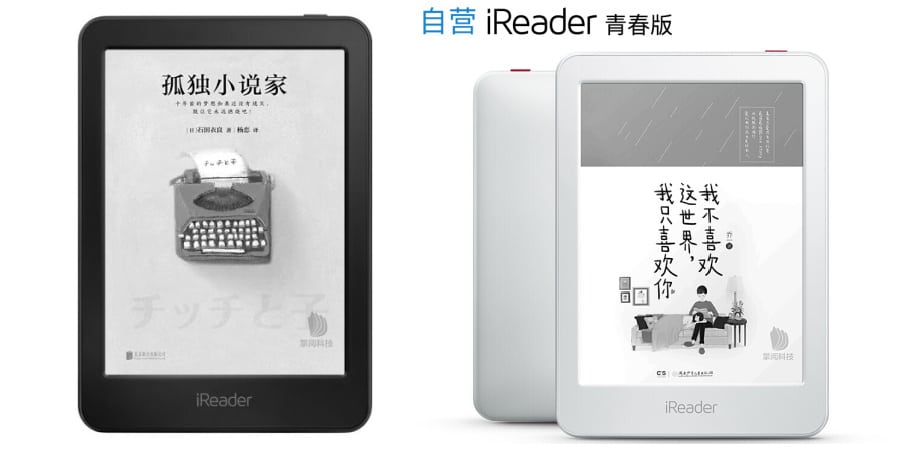

4. IREADER / ZHANGYUE (掌阅) (CHINESE BRAND)

Ebook reader Zhangyue (掌阅) made headlines in late 2020 when it was announced that Tiktok owner Bytedance would invest $170 million in the company.

Zhangyue, founded in 2008 in Beijing, is not just a producer of e-readers, it is also the online literature publisher behind the iReader platform (掌阅书城). Its most popular ebook reader in China at this time is the 6-inch Zhangyue iReader Light (掌阅iReader Light青春版), which is priced at ¥638 ($97) and comes with 8GB storage.

A much pricier model is the Smart X (¥3499/$539), which has 32GB storage and a 10.3 inch 1872×1404 resolution screen, making it just as big as the Onyx Boox Note Air and the iFlytek Smart Office X2. The iReader Smart X also comes with a Wacom pen for note-taking. There’s a review of this device on Gearbest.

The iReader Smart 2 is popular on shopping site JD.com, priced at ¥2299 ($353). It came out in 2020, and also is a note-taking device with 32GB storage and a 10.3 inch screen. The difference with the Smart X device mainly lies in its screen quality.

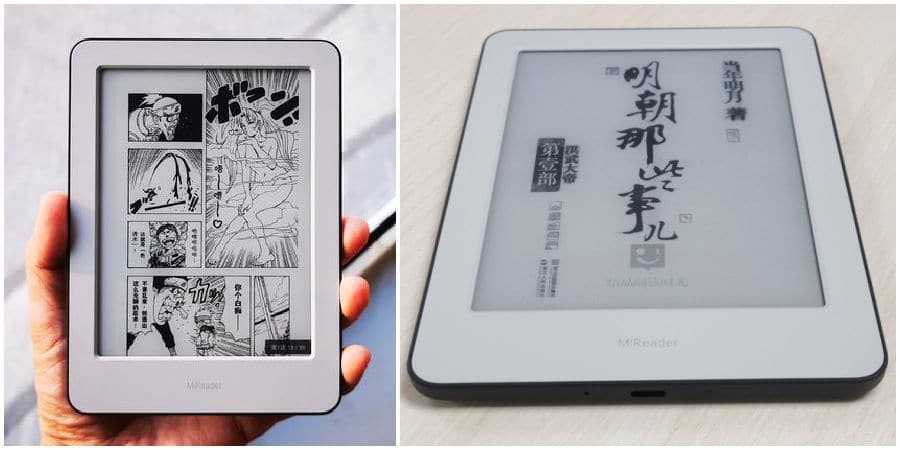

5. XIAOMI (CHINESE BRAND)

Beijing-brand Xiaomi is mostly known for being one of the world’s largest smartphone makers, but the tech company does so much more, from watches to earphones, TVs, scooters, and e-readers.

Priced at ¥599 ($92), the Xiaomi MiReader (小米多看电纸书), released in November 2019, is among the more popular e-reader devices in China at the moment. Mainly marketed for the Chinese market, it is Xiaomi’s first ebook reader which comes with a 6-inch e-Ink screen and 16GB storage. With its 1024×768 pixels at 212 PPI screen, it might not be as crisp and fast as other devices in this list, but its price is also much lower. This review at Goodereader was not positive at all, calling it “super slow and plodding.”

The MiReader also has a Pro device (小米多看电纸书Pro) available in China, which is ¥1299 ($200) and comes with a 7.8-inch 300 PPI screen and 32GB storage. The Xiaomi e-readers allow access to the WeChat Library, which is a great advantage for Chinese consumers (Kindle doesn’t allow access to the WeChat Library).

6. HANVON (汉王) (CHINESE BRAND)

Established in 1998, Hanwang is a pioneering company in character recognition technology and intelligent interactive products.

Although Hanvon is in the top 10 of China’s hottest e-book device brands, its Hanvon Gold House 3 model (汉王黄金屋3), priced at ¥799 ($123), is not nearly as popular as other devices in this list. The Hanvon Gold House comes with a 6-inch 1024×758 resolution screen and 4GB in storage. The device is marketed as being simple, stylish, and ergonomic.

7. TENCENT (CHINESE BRAND)

Chinese tech giant Tencent is mostly known for its social media and gaming products, but it also produces e-book devices.

The Tencent Pocket Reader (腾讯口袋阅) is small and lightweight with its 5.2 inches 1280×720 eInk screen, it comes with 8GB storage and is priced at ¥889 ($136). The device is centered around the Tencent ecosystem and provides access to the Tencent Library and bookstore.

Its small size makes this device different from other e-readers. It is the size of a smartphone, which is great if you really want an e-reader in your pocket, but less ideal if you are looking for a more comfortable reading experience. The Pocket Reader supports a 4G mobile card and can also make calls and do text messaging.

8. BOYUE (博阅) (CHINESE BRAND)

Boyue is a digital reading technology company founded in 2009. Throughout the years the company has released different e-book devices as well as digital note-taking devices.

The Boyue T80 model and its Likebook Mars are its best-sold devices in China. The Boyue T80 is priced at ¥1199 ($184) and has 8GB of storage, features an 8-inches 1024×768 screen, and supports SD.

The Likebook Mars is ¥1380 ($212) and comes with 16GB of storage, a 7.8 inch 1872×1404 screen, and it also has SD card support, which allows you to extend the storage capacity to 128GB.

9. OBOOK (国文) (CHINESE BRAND)

Guowen or OBOOK is an e-reader company established in 2010 as what was meant to be the Chinese answer to Kindle.

Its Dangdang E-reader 8 (当当阅读器8) is currently rising in popularity. It features a 6-inch 300 PPI resolution screen and 16GB of storage and is priced at ¥918 ($141).

10. SONY

Sony is perhaps not a name you’d expect in this list, since Sony seems to have exited the e-reader business some time ago.

There are only a few e-book devices by Sony that are still popular in China right now, and one of them is the 10.3-inch 1404×1872 screen Sony DPT-CP1 model that is priced at ¥4888 ($750). For this price, you get a lightweight, thin device that also serves as a digital note-taking tablet that syncs with PC or Mac.

The DPT-RP1/WC model is even pricier at ¥5299 ($815), for which you get a 13.3 inch 1650×2200 screen, which is comparable to the Onyx Boox Max Lumi.

By Manya Koetse

This is not a sponsored post. This article could contain links to online shops, which might allow us to earn a very small affiliate commission at zero extra cost to you – it helps us in maintaining this site. Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2021 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

Published

2 months agoon

June 8, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

JD.com’s 618 shopping festival is driving down book prices to such an extent that it has prompted a boycott by Chinese publishers, who are concerned about the financial sustainability of their industry.

When June begins, promotional campaigns for China’s 618 Online Shopping Festival suddenly appear everywhere—it’s hard to ignore.

The 618 Festival is a product of China’s booming e-commerce culture. Taking place annually on June 18th, it is China’s largest mid-year shopping carnival. While Alibaba’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival has been taking place on November 11th since 2009, the 618 Festival was launched by another Chinese e-commerce giant, JD.com (京东), to celebrate the company’s anniversary, boost its sales, and increase its brand value.

By now, other e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Pinduoduo have joined the 618 Festival, and it has turned into another major nationwide shopping spree event.

For many book lovers in China, 618 has become the perfect opportunity to stock up on books. In previous years, e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Dangdang (当当) would roll out tempting offers during the festival, such as “300 RMB ($41) off for every 500 RMB ($69) spent” or “50 RMB ($7) off for every 100 RMB ($13.8) spent.”

Starting in May, about a month before 618, the largest bookworm community group on the Douban platform, nicknamed “Buying Like Landsliding, Reading Like Silk Spinning” (买书如山倒,看书如抽丝), would start buzzing with activity, discussing book sales, comparing shopping lists, or sharing views about different issues.

Social media users share lists of which books to buy during the 618 shopping festivities.

This year, however, the mood within the group was different. Many members posted that before the 618 season began, books from various publishers were suddenly taken down from e-commerce platforms, disappearing from their online shopping carts. This unusual occurrence sparked discussions among book lovers, with speculations arising about a potential conflict between Chinese publishers and e-commerce platforms.

A joint statement posted in May provided clarity. According to Chinese media outlet The Paper (@澎湃新闻), eight publishers in Beijing and the Shanghai Publishing and Distribution Association, which represent 46 publishing units in Shanghai, issued a statement indicating they refuse to participate in this year’s 618 promotional campaign as proposed by JD.com.

The collective industry boycott has a clear motivation: during JD’s 618 promotional campaign, which offers all books at steep discounts (e.g., 60-70% off) for eight days, publishers lose money on each book sold. Meanwhile, JD.com continues to profit by forcing publishers to sell books at significantly reduced prices (e.g., 80% off). For many publishers, it is simply not sustainable to sell books at 20% of the original price.

One person who has openly spoken out against JD.com’s practices is Shen Haobo (沈浩波), founder and CEO of Chinese book publisher Motie Group (磨铁集团). Shen shared a post on WeChat Moments on May 31st, stating that Motie has completely stopped shipping to JD.com as it opposes the company’s low-price promotions. Shen said it felt like JD.com is “repeatedly rubbing our faces into the ground.”

Nevertheless, many netizens expressed confusion over the situation. Under the hashtag topic “Multiple Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Book Promotions” (#多家出版社抵制618图书大促#), people complained about the relatively high cost of physical books.

With a single legitimate copy often costing 50-60 RMB ($7-$8.3), and children’s books often costing much more, many Chinese readers can only afford to buy books during big sales. They question the justification for these rising prices, as books used to be much more affordable.

Book blogger TaoLangGe (@陶朗歌) argues that for ordinary readers in China, the removal of discounted books is not good news. As consumers, most people are not concerned with the “life and death of the publishing industry” and naturally prefer cheaper books.

However, industry insiders argue that a “price war” on books may not truly benefit buyers in the end, as it is actually driving up the prices as a forced response to the frequent discount promotions by e-commerce platforms.

China News (@中国新闻网) interviewed publisher San Shi (三石), who noted that people’s expectations of book prices can be easily influenced by promotional activities, leading to a subconscious belief that purchasing books at such low prices is normal. Publishers, therefore, feel compelled to reduce costs and adopt price competition to attract buyers. However, the space for cost reduction in paper and printing is limited.

Eventually, this pressure could affect the quality and layout of books, including their binding, design, and editing. In the long run, if a vicious cycle develops, it would be detrimental to the production and publication of high-quality books, ultimately disappointing book lovers who will struggle to find the books they want, in the format they prefer.

This debate temporarily resolved with JD.com’s compromise. According to The Paper, JD.com has started to abandon its previous strategy of offering extreme discounts across all book categories. Publishers now have a certain degree of autonomy, able to decide the types of books and discount rates for platform promotions.

While most previously delisted books have returned for sale, JD.com’s silence on their official social media channels leaves people worried about the future of China’s publishing industry in an era dominated by e-commerce platforms, especially at a time when online shops and livestreamers keep competing over who has the best book deals, hyping up promotional campaigns like ‘9.9 RMB ($1.4) per book with free shipping’ to ‘1 RMB ($0.15) books.’

This year’s developments surrounding the publishing industry and 618 has led to some discussions that have created more awareness among Chinese consumers about the true price of books. “I was planning to bulk buy books this year,” one commenter wrote: “But then I looked at my bookshelf and saw that some of last year’s books haven’t even been unwrapped yet.”

Another commenter wrote: “Although I’m just an ordinary reader, I still feel very sad about this situation. It’s reasonable to say that lower prices are good for readers, but what I see is an unfavorable outlook for publishers and the book market. If this continues, no one will want to work in this industry, and for readers who do not like e-books and only prefer physical books, this is definitely not a good thing at all!”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Chinese Sun Protection Fashion: Move over Facekini, Here’s the Peek-a-Boo Polo

From facekini to no-face hoodie: China’s anti-tan fashion continues to evolve.

Published

2 months agoon

June 6, 2024

It has been ten years since the Chinese “facekini”—a head garment worn by Chinese ‘aunties’ at the beach or swimming pool to prevent sunburn—went international.

Although the facekini’s debut in French fashion magazines did not lead to an international craze, it did turn the term “facekini” (脸基尼), coined in 2012, into an internationally recognized word.

The facekini went viral in 2014.

In recent years, China has seen a rise in anti-tan, sun-protection garments. More than just preventing sunburn, these garments aim to prevent any tanning at all, helping Chinese women—and some men—maintain as pale a complexion as possible, as fair skin is deemed aesthetically ideal.

As temperatures are soaring across China, online fashion stores on Taobao and other platforms are offering all kinds of fashion solutions to prevent the skin, mainly the face, from being exposed to the sun.

One of these solutions is the reversed no-face sun protection hoodie, or the ‘peek-a-boo polo,’ a dress shirt with a reverse hoodie featuring eye holes and a zipper for the mouth area.

This sun-protective garment is available in various sizes and models, with some inspired by or made by the Japanese NOTHOMME brand. These garments can be worn in two ways—hoodie front or hoodie back. Prices range from 100 to 280 yuan ($13-$38) per shirt/jacket.

The no-face hoodie sun protection shirt is sold in various colors and variations on Chinese e-commerce sites.

Some shops on Taobao joke about the extreme sun-protective fashion, writing: “During the day, you don’t know which one is your wife. At night they’ll return to normal and you’ll see it’s your wife.”

On Xiaohongshu, fashion commenters note how Chinese sun protective clothing has become more extreme over the past few years, with “sunburn protection warriors” (防晒战士) thinking of all kinds of solutions to avoid a tan.

Although there are many jokes surrounding China’s “sun protection warriors,” some people believe they are taking it too far, even comparing them to Muslim women dressed in burqas.

Image shared on Weibo by @TA们叫我董小姐, comparing pretty girls before (left) and nowadays (right), also labeled “sunscreen terrorists.”

Some Xiaohongshu influencers argue that instead of wrapping themselves up like mummies, people should pay more attention to the UV index, suggesting that applying sunscreen and using a parasol or hat usually offers enough protection.

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?