Chinese Apps

Top 10 Apps for Studying Chinese (iOS/Android)

Learning Chinese through smartphone or tablet? Here are 10 recommended apps to study Mandarin.

Published

7 years agoon

One of the easiest ways to start learning Chinese or improve language skills is to use apps. What’s on Weibo has listed 10 recommended apps that are helpful to any learner of Mandarin.

One of the most-asked questions by people who want to learn Mandarin is: where do I start? Do you begin by learning characters, do you start out with tones, or just focus on the pinyin? For more advanced learners, there is another challenge. How do you make sure you do not lose the knowledge you already have and to how to keep on improving your language skills?

Although learners should always work with whatever methods are most effective for them, the most productive way of studying Mandarin is to study its different components at the same time. Studying new words on paper without learning their tones is not recommended, neither is focusing on pinyin without learning the characters. Instead, it’s better to get a grasp on all the different aspects of this rich language.

Some of the 10 apps in this list are Chinese apps meant for a Chinese audience, and not necessarily meant for Chinese language learners – but they are nevertheless excellent learning tools.

Here are some What’s on Weibo favorites for Android, iPhone or iPad, from beginners to advanced levels of Mandarin.

1. Pleco Software Dictionary

A confession from the editor: Pleco has been my best friend ever since I started studying Chinese. At the time, I once invested an amount that seemed like a huge sum of money as I was working side jobs as a beginning student to purchase the app’s professional package. I used a hand-me-down Palm handheld (!) at the time, but since then, the Pleco support team has never failed me as I transferred the dictionaries to my first iPhone, my first Samsung, and even my first iPad. The fact that many years had passed since my first investment was never an issue.

Although Pleco’s service is praiseworthy, it is all about the app itself in the end. Pleco calls itself “The #1 Chinese dictionary app for iOS and Android” and it is hard to argue with that. It is suitable for anyone studying Chinese on an elementary, intermediate, or advanced level. What is good about Pleco is that it has a great range of dictionaries and has an easy handwriting recognizer; even if your handwriting in Chinese is not that great, it will still get the character you need.

The major plus for Pleco is that it is much more than a dictionary alone. It has an add-on optical character recognizer that will help you read offline texts, and the “clip reader” function is super handy to copy Chinese texts on smartphone/table – just copy the text and navigate to Pleco to find the text and tap words and characters for their meanings.

Outlier Linguistics has also partnered up with Pleco, adding its excellent Chinese character dictionary to the add-ons. The Essential edition contains all the essential info about each Chinese character, while the Expert Edition is for those who want to dive deep into the history and etymology of Chinese characters.

Another tip: with Pleco, you can train your Chinese vocabulary through flashcards: add any words you do not know to a category (for example: ‘My Chinese Business Vocabulary’, or ‘Dirty Words in Chinese’), and then quiz yourself through Pleco’s ‘test’ function. It will repeat all the words you got wrong until you have a 100% score.

The free version is ok, but for learners who are serious about learning Chinese (especially when you’re dealing with Chinese for your studies) the professional package is recommended and you’ll be able to take it along with you, even when you switch from the ancient Palm to the latest iPhone.

Price: free (elementary), US $29.99 for basic package (bundles through Android), US $99.99 (professional package) + rich selection of optional add-ons.

Compatibility: iPhone/iPad & Android

Where to get:

iPhone: Pleco Chinese Dictionary – Pleco Inc.

iPad: Pleco Chinese Dictionary – Pleco Inc.

Android: Pleco Chinese Dictionary

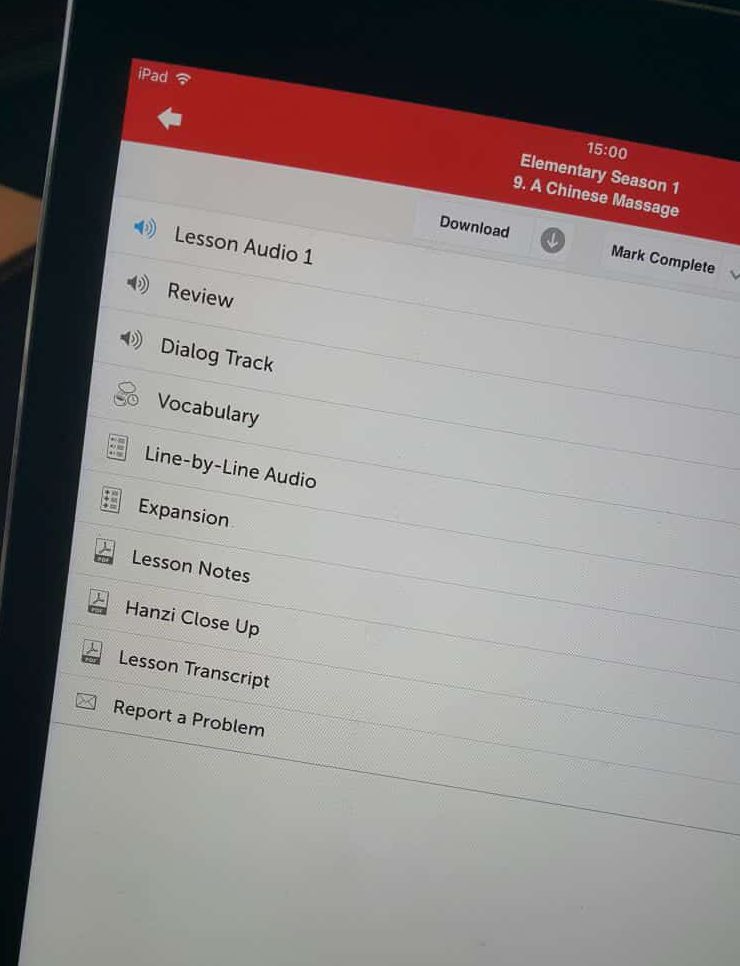

2. Chinese Class 101 (by Innovative Language)

Whether you are on the road or at home, online or offline, Chinese Class 101 offers Mandarin comprehensive learning courses that you can easily integrate into your everyday life. The lesson-per-lesson audio system makes it easy to listen and practice to bite-sized conversations and fragments (which can all be downloaded) while you’re driving to work or cooking dinner.

The app offers lessons from the absolute beginner’s level to the very advanced level. Every lesson consists of an audio class of ±10 minutes that usually features a conversation, an audio review of vocabulary, a line-by-line display of the conversation (in English, pinyin, simplified & traditional Chinese), and lesson notes. Note: the overviews and transcripts only come with the premium subscription – if you only want to do audio, you’ll be fine with basic, but to get a complete overview of the texts and words you’d have to go for the premium one ($10/month).

Chinese Class 101 also provides the option to have 1-on-1 interaction with a personal teacher through the app, which only comes with the more expensive premium plus subscription.

If you are not learning Chinese through a school or university, this program is a very effective way of learning Mandarin. One of the key things of this course is the way it repeats the things you’ve learned to really make it stick in your head. (Also, their Korean programme is very good if you’re considering to take on an extra language…).

Price: This app works with a subscription system. It is free to try for a week, US $5/month for the basic package (access to all audio archives), US $10/month for the premium package (includes wordlists and transcripts) and $23/month for the premium plus (includes option for 1-on-1 teaching).

Compatibility: iPhone/iPad & Android and desktop

Where to get:

www.chineseclass101.com

3. Pera Pera Pop Up Dictionary

Ok, ok, this is not technically an app – it is a plugin. But it needs to be high up in this list for anyone learning Chinese. Pera Pera is a pop-up dictionary add-on for Chrome or Firefox. It gives the English definition for Chinese texts, making it infinitely easier for those struggling with characters to read Chinese online. Pro’s: easy to install, easy to use, and translations for many modern names or slang words. Downside: if you use Pera Pera too often, you will get lazy and won’t actually learn the characters. Try to only activate this add-on when you really do not know the character.

A major plus of Perapera is that it often gives the translation for relatively new ‘internet slang’ words or typically online words, making it an effective tool for the modern-day learner of Chinese who scrolls through Chinese texts.

If you are looking for a similar feature for your Android smartphone, Pleco (number 1 in this list) has a ‘screen reader’ feature for that.

We’ve been told that in the lastest Firefox version, Pera Pera does not work – in that case we recommend the Zhongwen Popup Dictionary add-on for Firefox.

Price: free

Compatibility: Firefox and Chrome

Where to get:

Chrome Web Store

Firefox Addons

4. Yuntu TV (云图直播)

Immersing yourself in the language is the best way to learn Chinese. If you’re not in an environment where you are naturally surrounded by the language on a daily basis, you’ll have to create that environment for yourself. Luckily, there are many live TV & radio apps that stream countless channels for you to enjoy.

Yuntu TV is a Chinese live streaming app where you can see all the CCTV channels and many other Chinese channels such as Zhejiang TV, Hunan TV, or Shenzhen TV.

If you would like to listen to Chinese language through TV dramas, Viki Rakuten has a great selection (free, availability depends on region).

Price: free

Compatibility: Android, iPhone, iPad

Where to get:

iPhone: 云图手机电视NEW-在线高清电视综艺体育直播

iPad: 云图手机电视NEW-高清电视直播视频播放器

Official Site: http://www.yuntutv.net/

5. Baobei Ting Ting (宝贝听听)Bedtime Stories

If you think Chinese news programmes are still too difficult, and you prefer to something that is a bit easier to digest, why not practice your Mandarin listening skills by checking out the stories Chinese kids like to listen to? ‘Baby Ting’ or ‘Baobei Ting Ting’ (宝贝听听)is a popular storytelling app by Tencent QQ that has thousands of stories to choose from in different categories; starting from the 0-3 age group, 4-6 age group, 7+ age group, to the national classics, modern fairy tales, etc.

The variety of stories that this app provides makes it a perfect tool for non-native speakers who study Chinese. Those at the intermediate level can start with the stories for the young kids and try to train their way up.

Mind you; like the Yuntu TV app, this is an app that is Chinese and has no English. It is, therefore, better if you already can read some Chinese characters when using this app. This app can be linked to your WeChat account, and offers in-app purchases.

Price: free

Compatibility: Android, iPhone, iPad

Where to get:

iPhone:宝贝听听-睡前儿童故事儿歌大全 – 北京企鹅童话科技有限公司

iPad: 宝贝听听-睡前儿童故事儿歌大全 – 北京企鹅童话科技有限公司 or 宝贝童话 – 北京企鹅童话科技有限公司

Android: 宝贝听听-睡前儿童故事儿歌大全 – 北京企鹅童话科技有限公司 (not on Google play store).

6. ChinesePod

Chinesepod is a well-known educational platform providing audiovisual lessons for people learning Chinese – from newbie to advanced level. It promotes an “alternative way of learning Chinese” and focuses on teaching spoken Chinese through video lessons.

All the material on the Chinesepod platforms can be somewhat overwhelming, but don’t worry, you do not actually need to do all the lessons one by one; just pick whatever lessons you find interesting within your level of proficiency and start from there.

Price: Chinesepod has various subscription options. The basic option ($14/month) offers access to the complete lesson library and offers the printable lesson notes, whereas the premium ($29/month) option also offers grammatical explanations, custom vocabulary lists, and the full Android + iOS apps.

Where to get:

chinesepod.com

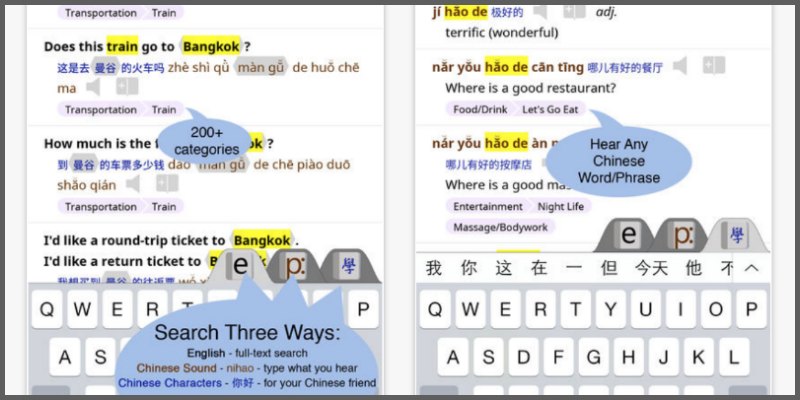

7. Talking Chinese–English–Chinese Phrasebook

Many apps promoting ‘Mandarin phrases’ are often disappointing because of their limited range of topics and phrases. This app by Paiboon and Word in the Hand, however, is worth your time – although it is somewhat pricey. It is suitable for travelers to China who want to be able to communicate their basic needs, as well as for those studying Chinese to grasp basic sentences and practice tones.

The phrasebook offers more than 15,000 words and ready-to-use phrases in over 250 practical categories, from all the basics to situations relating to, for example, legal cases, superstitions, or romance (the ‘swearing’ category is quite amusing, providing different ways to insult someone.) All sentences and words are displayed together with audio, characters, and pinyin.

Price: $14.99

Compatibility: iPhone/iPad

Where to get:

iPad/iPhone: Talking Chinese–English–Chinese Phrasebook

8. Feed Me (Mandarin)! by Pencilbot

What?! Are we seriously recommending a purple dragon that eats trains and mice as a Chinese learning language tool? Yes, we are. Because if it works for kids, it works for you. This purple dragon needs to be fed. A very clear voiceover will give you instructions in Chinese on what to feed him. You’ll find out soon enough if you’ve fed him the wrong stuff: he’ll be displeased and will show it.

This is an app designed by Pencilbot, which also provides the “Feed Me!” app in Korean, Japanese, Arabic, and many other languages. Although the app is targeted at kids around the age of 5-6, it is also useful for adults to feed the dragon the red apples, blue birds, or yellow squares. Not just because the the Mandarin is beautifully pronounced, but also because the little dragon cheers you on in the cutest way when you get it right. If you tickle his belly he will start giggling. After playing this, you will know how to pronounce colors, shapes, numbers, animals, fruits, and more in Mandarin. If you don’t like it, your kid will.

Price: $1.99

Compatibility: iPhone/iPod/iPad and Android

Where to get:

iPhone: Feed Me! Chinese – Edutainment Resources, Inc.

iPad: Feed Me! Chinese – Edutainment Resources, Inc.

Android: Feed Me! Chinese – Edutainment Resources, Inc.

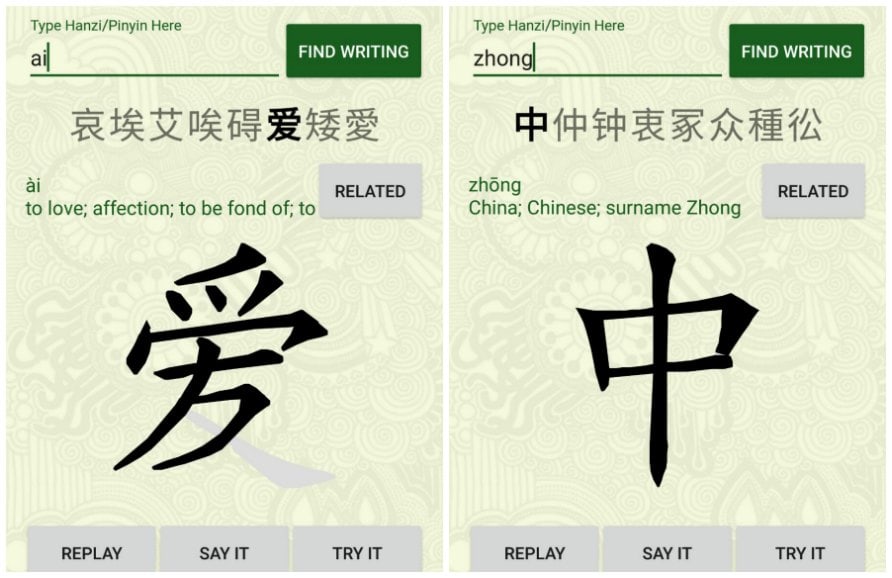

9. Hanzi Writer

Because learning Chinese means learning to listen, speak, read and write, this list wouldn’t be complete without an app that focuses on teaching how to properly write characters. This is what Hanzi Writer does very well.

Users can type in the pinyin of a character (for example, ‘ai’ for love), and select the character they want to see. Hanzi Writer shows the stroke order and how to write, and then gives you the opportunity to try for yourself. Learning to properly write characters is all about repeating repeating repeating, and this app is perfect for that.

Price: free version for Android with ads and $5.99 for iOs

Where to get:

iPhone – Hanzi Writer – Ali Lim

iPad – Hanzi Writer – Ali Lim

Android – Hanzi Writer – Ali Lim

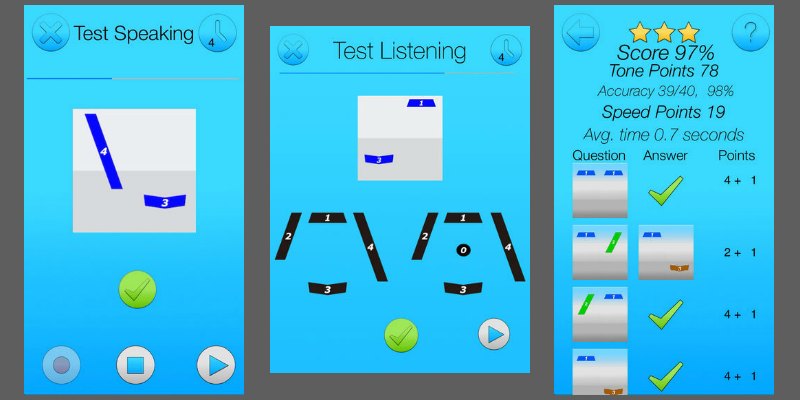

10. Laokang Tone Test

Recognizing and pronouncing tones the right way is essential for your everyday use of Mandarin. Understanding or saying the wrong tones can lead to awkward situations. That is why this Laokang Tone Test is a must-have app if you are in the early stages of learning Chinese. The app is very simple and basic: it will train both your hearing of tones and your pronunciation. The layout of the app is not very pretty, but it works like a charm.

Price: free

Compatibility: iPhone/iPad

Where to get:

iTunes store

This list can still change and does not include all of the apps mentioned by our readers on Twitter or Facebook. Some of you enjoy Memrise to study Chinese, while others dislike its latest changes (what do you think?). If you want to add your favorite app, please let us know in the comments below.

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2017 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Digital

China’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

It’s Gaokao time! For the first time, China’s Gaokao essay topic was about the latest AI developments, triggering discussions on social media.

Published

2 months agoon

June 7, 2024

This week, China’s National College Entrance Exams, better known as the “Gaokao” (高考), became one of the most-discussed topics on Chinese social media. ‘Gaokao,’ ‘AI,’ and ‘Gaokao essay’ were the hottest words on Weibo by the end of the week.

The Gaokao (literally: ‘higher exams’) are a prerequisite for entering China’s higher education institutions and are usually taken by students in their last year of senior high school. June 7th marked the first day of the Gaokao, which will continue until June 9th.

For the over 13.4 million participating students, the Gaokao week is a pivotal moment. Scoring high on this exam can grant access to better colleges, significantly improving their chances of obtaining a good job after graduation. Given the potentially life-changing results, the Gaokao period is a stressful time for both students and their parents.

The Gaokao essay (高考作文) is a significant component of the Chinese language exam, testing students’ writing skills, critical thinking, and ability to express ideas coherently. The essay, which must be completed within a limited time, requires students to discuss given topics.

These topics are generally related to Chinese society and culture, consistently attracting attention on social media. This year, multiple essay questions were related to AI and social media.

Those taking the Beijing exam (北京卷), for example, received a question related to the “like” function on WeChat, suggesting that some people feel strongly about the number of “likes” they receive and give, asking students to reflect on the phenomenon of receiving and giving “likes” on social media.

But the question receiving the most attention on social media was part of the New Curriculum Standard Test I (新课标I卷), which is distributed among different provinces.

Students vs. Chatbots: Letting AI Write an Essay on AI

Students received the following topic prompt for their Gaokao essay, which should be at least 800 characters long:

“With the spread of the internet and AI applications, we can quickly get answers to more and more questions. Will this also lead to us having fewer problems?” (随着互联网的普及、人工智能的应用,越来越多的问题能很快得到答案。那么,我们的问题是否会越来越少?)

The question sparked discussions because it was the first time a Gaokao essay question focused on AI applications designed to interact with users, like ChatGPT.

Although many thought the essay question was easy—unlike this year’s math exam—it still generated some interesting reflections.

Some Weibo users responded that the answer to the question was within the question itself. One Weibo blogger answered: “If there were no AI, we wouldn’t have this question, so problems/questions related to AI will only increase. The emergence of new things will inevitably be accompanied by new problems.”

Others commented on the concerns brought by the emergence of AI applications like ChatGPT. In early 2023, hashtags such as “Ten Professions That Could be Replaced by ChatGPT” (#可能被ChatGPT取代的10大职业#) gained a lot of attention on Chinese social media, where many were concerned that jobs from various industries, including customer service, programming, media, education, market research, finance, etc., would soon be done by AI chatbots instead of humans.

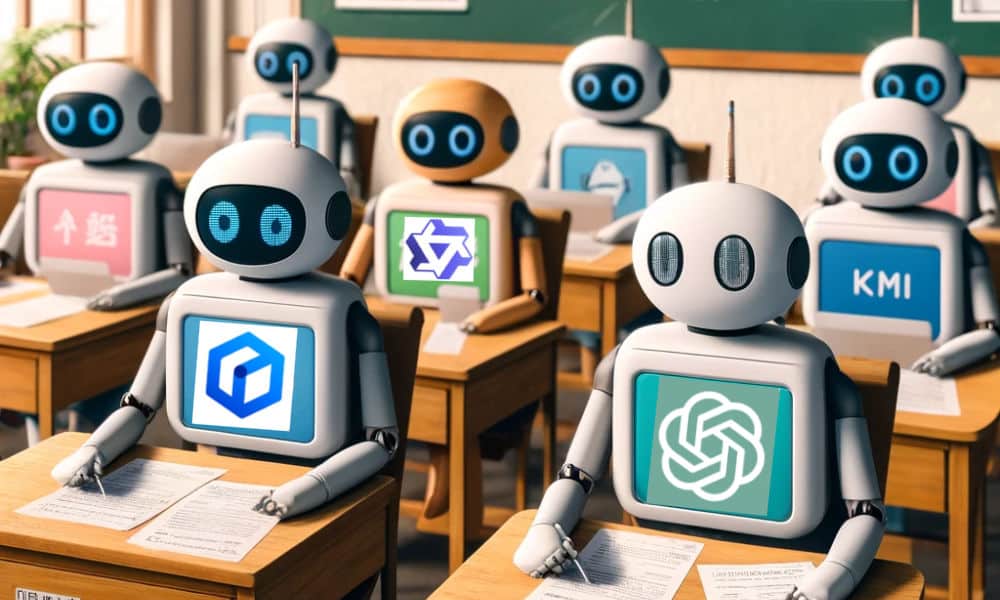

In line with this thought and the AI theme of this year’s Gaokao essay, netizens and some Chinese media outlets decided to let various language models take the exam and see how they would perform: could AI actually do better in writing an essay about AI than Chinese students? (Related hashtags: #让AI写高考作文#, #假如AI写高考语文作文#; #ChatGPT来交卷了#).

Xinhua, for example, asked Open AI’s ChatGPT to answer various questions. Sina Tech (新浪科技) also asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT to answer the AI-related essay question, along with Chinese chatbots, like Baidu’s Erniebot (文心一言), Tencent’s Yuanbao (元宝), iFlytek’s Sparkdesk (星火), and Alibaba’s Tongyi Qianwen (通义千问). Toutiao News did the same, letting three chatbots (ChatGPT, Erniebot, Tongyi Qianwen) compete against each other.

There is no general consensus on how well these AI chatbots can write a Gaokao essay. Although compared to last year, there are now more and better domestic AI models, OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 is generally still seen as the best chatbot out there.

This was its answer (originally in Chinese, translated to English with ChatGPT):

New Issues and Thoughts Brought by Technological Progress

With the popularization of the internet and the application of artificial intelligence, we can quickly obtain a large amount of information, and many questions can be answered in a short time. However, does this mean that we will have fewer questions? I believe the answer is no.

Firstly, although technology provides us with convenience, new technologies also bring new problems. The popularization of the internet has made information dissemination faster, but at the same time, the authenticity and accuracy of information have become new concerns. Fake news, information overload, and privacy breaches are increasingly prominent issues. These new problems need to be identified, understood, and resolved by us.

Secondly, the application of artificial intelligence, although it improves efficiency, also brings ethical and social issues. The transparency of AI decision-making, algorithmic bias, and the impact on the job market are all urgent issues that society needs to address. People need to constantly raise new questions to ensure a balance between technological progress and social welfare.

Furthermore, the development of technology prompts us to reflect more deeply on humanity itself. We need to rethink the relationship between humans and technology and consider the role and boundaries of technology in our lives. These philosophical issues are more important than ever.

Therefore, technological progress does not reduce our questions but rather prompts more new questions and reflections. It is these constantly emerging questions that drive social progress and human thought. We need to embrace the challenges brought by technology with a more open and critical attitude and actively seek solutions.

Although the domestic chatbots gave somewhat different answers, the overall tone was similar, though some commenters argued that ChatGPT was still the strongest, along with iFlytek’s Sparkdesk.

An online poll asking Weibo users to grade the ChatGPT essay from lower than 20 points up to the full 60 points saw divided responses, though a majority rated it as lower than 20 points.

How well can ChatGPT write an essay about AI? Opinions are divided.

This shows that many commenters think that AI chatbots are still not able to beat humans when it comes to writing Gaokao essays.

Commenters reacted to the various AI-generated essays in various ways, including:

• “Actually, none of them are very good. They are too formulaic and standardized, lacking the natural creativity and originality that humans possess.”

• “They just give soulless standard answers.”

• “It’s all about ‘firstly,’ ‘secondly,’ ‘furthermore.'”

• “There are no examples, no points proven; it should be a low grade.”

• “It’s just too stiff.”

• “This is like reading reports, not essays.”

• “AI places more emphasis on logic, which aligns with the writing style of foreigners.”

• “There’s no feeling in these essays; there’s a certain kind of AI feeling to AI.”

Meanwhile, some bloggers are taking up the challenge and are publishing their own online essays in response to the Gaokao question.

Some of them are not worried that chatbots will take over their critical tasks: “AI will be AI. There’s no connection to the social realities, and it’s as cold as ice.”

“Their words might make sense, but they lack feeling.”

But for some discussing the topic, they have come to realize that they are already depending too much on digital tools and AI applications for their everyday tasks, writing: “I made an attempt to write an essay, but discovered I already forgot how to do it!” For them, the discussion itself is a wake-up call that writing an essay from scratch is a skill that requires practice and cannot be fully replaced by chatbots, making personal creativity essential to score points and avoid the ‘AI-fication’ of texts.

PS:

In his book China’s Millennials, Eric Fish describes the limits on Chinese students’ answers; taboo responses, such as those containing harsh criticisms of the Chinese government or society, could potentially lead to failure. Although the essay is purportedly meant to showcase the student’s creativity, it must adhere to the unwritten rules of what is socially acceptable.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

Going All In on Short Streaming: About China’s Online ‘Micro Drama’ Craze

For viewers, they’re the ultimate guilty pleasure. For producers, micro dramas mean big profit.

Published

4 months agoon

March 26, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

PREMIUM CONTENT

Closely intertwined with the Chinese social media landscape and the fast-paced online entertainment scene, micro dramas have emerged as an immensely popular way to enjoy dramas in bite-sized portions. With their short-format style, these dramas have become big business, leading Chinese production studios to compete and rush to create the next ‘mini’ hit.

In February of this year, Chinese social media started flooding with various hashtags highlighting the huge commercial success of ‘online micro-short dramas’ (wǎngluò wēiduǎnjù 网络微短剧), also referred to as ‘micro drama’ or ‘short dramas’ (微短剧).

Stories ranged from “Micro drama screenwriters making over 100k yuan [$13.8k] monthly” to “Hengdian building earning 2.8 million yuan [$387.8k] rent from micro dramas within six months” and “Couple earns over 400 million [$55 million] in a month by making short dramas,” all reinforcing the same message: micro dramas mean big profits. (Respectively #短剧爆款编剧月入可超10万元#, #横店一栋楼半年靠短剧租金收入280万元#, #一对夫妇做短剧每月进账4亿多#.)

Micro dramas, taking China by storm and also gaining traction overseas, are basically super short streaming series, with each episode usually lasting no more than two minutes.

From Horizontal to Vertical

Online short dramas are closely tied to Chinese social media and have been around for about a decade, initially appearing on platforms like Youku and Tudou. However, the genre didn’t explode in popularity until 2020.

That year, China’s State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT) introduced a “fast registration and filing module for online micro dramas” to their “Key Online Film and Television Drama Information Filing System.” Online dramas or films can only be broadcast after obtaining an “online filing number.”

Chinese streaming giants such as iQiyi, Tencent, and Youku then began releasing 10-15 minute horizontal short dramas in late 2020. Despite their shorter length and faster pace, they actually weren’t much different from regular TV dramas.

Soon after, short video social platforms like Douyin (TikTok) and Kuaishou joined the trend, launching their own short dramas with episodes only lasting around 3 minutes each.

Of course, Douyin wouldn’t miss out on this trend and actively contributed to boosting the genre. To better suit its interface, Douyin converted horizontal-screen dramas into vertical ones (竖屏短剧).

Then, in 2021, the so-called mini-program (小程序) short dramas emerged, condensing each episode to 1-2 minutes, often spanning over 100 episodes.

These short dramas are advertised on platforms like Douyin, and when users click, they are directed to mini-programs where they need to pay for further viewing. Besides direct payment revenue, micro dramas may also bring in revenue from advertising.

‘Losers’ Striking Back

You might wonder what could possibly unfold in a TV drama lasting just two minutes per episode.

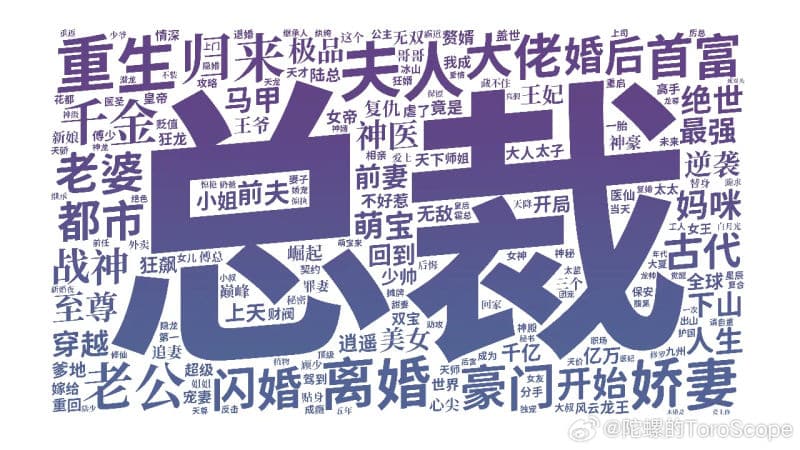

The Chinese cultural media outlet ‘Hedgehog Society’ (刺猬公社) collected data from nearly 6,000 short dramas and generated a word cloud based on their content keywords.

In works targeted at female audiences, the most common words revolve around (romantic) relationships, such as “madam” (夫人) and “CEO” (总裁). Unlike Chinese internet novels from over a decade ago, which often depicted perfect love and luxurious lifestyles, these short dramas offer a different perspective on married life and self-discovery.

According to Hedgehog Society’s data, the frequency of the term “divorce” (离婚) in short dramas is ten times higher than “married” (结婚) or “newlyweds” (新婚). Many of these dramas focus on how the female protagonist builds a better life after divorce and successfully stands up to her ex-husband or to those who once underestimated her — both physically and emotionally.

One of the wordclouds by 刺猬公社.

In male-oriented short dramas, the pursuit of power is a common theme, with phrases like “the strongest in history” (史上最强) and “war god” (战神) frequently mentioned. Another surprising theme is “matrilocal son” (赘婿), the son-in-law who lives with his wife’s family. In China, this term is derogatory, particularly referring to husbands with lower economic income and social status than their wives, which is considered embarrassing in traditional Chinese views. However, in these short dramas, the matrilocal son will employ various methods to earn the respect of his wife’s family and achieve significant success.

Although storylines differ, a recurring theme in these short dramas is protagonists wanting to turn their lives around. This desire for transformation is portrayed from various perspectives, whether it’s from the viewpoint of a wealthy, elite individual or from those with lower social status, such as divorced single women or matrilocal son-in-laws. This “feel-good” sentiment appears to resonate with many Chinese viewers.

Cultural influencer Lu Xuyu (@卢旭宁) quoted from a forum on short dramas, explaining the types of short dramas that are popular: Men seek success and admiration, and want to be pursued by beautiful women. Women seek romantic love or are still hoping the men around them finally wake up. One netizen commented more bluntly: “They are all about the counterattack of the losers (屌丝逆袭).”

The word used here is “diaosi,” a term used by Chinese netizens for many years to describe themselves as losers in a self-deprecating way to cope with the hardships of a competitive life, in which it has become increasingly difficult for Chinese youths to climb the social ladder.

Addicted to Micro Drama

By early 2024, the viewership of China’s micro dramas had soared to 120 million monthly active users, with the genre particularly resonating with lower-income individuals and the elderly in lower-tier markets.

However, short dramas also enjoy widespread popularity among many young people. According to data cited by Bilibili creator Caoxiaoling (@曹小灵比比叨), 64.9% of the audience falls within the 15-29 age group.

For these young viewers, short dramas offer rapid plot twists, meme-worthy dialogues, condensing the content of several episodes of a long drama into just one minute—stripping away everything except the pure “feel-good” sentiment, which seems rare in the contemporary online media environment. Micro dramas have become the ultimate ‘guilty pleasure.’

Various micro dramas, image by Sicomedia.

Even the renowned Chinese actress Ning Jing (@宁静) admitted to being hooked on short dramas. She confessed that while initially feeling “scammed” by the poor production and acting, she became increasingly addicted as she continued watching.

It’s easy to get hooked. Despite criticisms of low quality or shallowness, micro dramas are easy to digest, featuring clear storylines and characters. They don’t demand night-long binge sessions or investment in complex storylines. Instead, people can quickly watch multiple episodes while waiting for their bus or during a short break, satisfying their daily drama fix without investing too much time.

Chasing the gold rush

During the recent Spring Festival holiday, the Chinese box office didn’t witness significant growth compared to previous years. In the meantime, the micro drama “I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother” (我在八零年代当后妈), shot in just 10 days with a post-production cost of 80,000 yuan ($11,000), achieved a single-day revenue exceeding 2 million yuan ($277k). It’s about a college girl who time-travels back to the 1980s, reluctantly getting married to a divorced pig farm owner with kids, but unexpectedly falling in love.

Despite its simple production and clichéd plot, micro dramas like this are drawing in millions of viewers. The producer earned over 100 million yuan ($13 million) from this drama and another short one.

“I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother” (我在八零年代当后妈).

The popularity of short dramas, along with these significant profits, has attracted many people to join the short drama industry. According to some industry insiders, a short drama production team often involves hundreds or even thousands of contributors who help in writing scripts. These contributors include college students, unemployed individuals, and online writers — seemingly anyone can participate.

By now, Hengdian World Studios, the largest film and television shooting base in China, is already packed with crews filming short dramas. With many production teams facing a shortage of extras, reports have surfaced indicating significant increases in salaries, with retired civil workers even being enlisted as actors.

Despite the overwhelming success of some short dramas like “I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother,” it is not easy to replicate their formula. The screenwriter of the time-travel drama, Mi Meng (@咪蒙的微故事), is a renowned online writer who is very familiar with how to use online strategies to draw in more viewers. For many average creators, their short drama production journey is much more difficult and less fruitful.

But with low costs and potentially high returns, even if only one out of a hundred productions succeeds, it could be sufficient to recover the expenses of the others. This high-stakes, cutthroat competition poses a significant challenge for smaller players in the micro drama industry – although they actually fueled the genre’s growth.

As more scriptwriters and short dramas flood the market, leading to content becoming increasingly similar, the chances of making profits are likely to decrease. Many short drama platforms have yet to start generating net profits.

This situation has sparked concerns among netizens and critics regarding the future of short dramas. Given the genre’s success and intense competition, a transformation seems inevitable: only the shortest dramas that cater to the largest audiences will survive.

In the meantime, however, netizens are enjoying the hugely wide selection of micro dramas still available to them. One Weibo blogger, Renmin University Professor Ma Liang (@学者马亮), writes: “I spent some time researching short videos and watched quite a few. I must admit, once you start, you just can’t stop. ”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?