China Insight

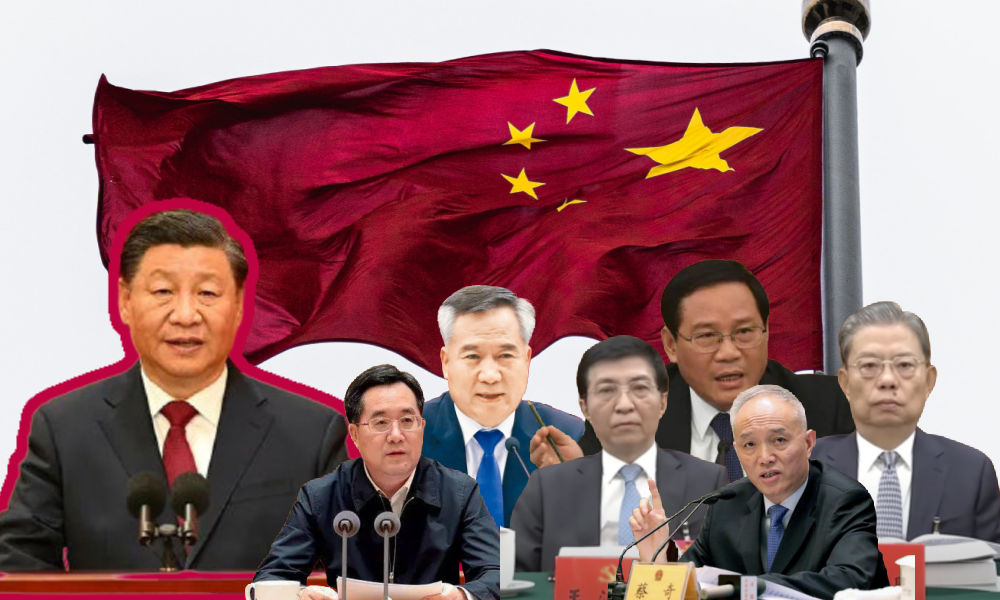

Follow the Leaders: These Are All the Members of China’s 20th Central Committee & Politburo Standing Committee

Full list of names including the members of China’s new 20th Central Committee, the Politburo, and its Standing Committee.

Published

2 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

Which Party members will lead China in the next five years? These are the names you need to know: all the full members of China’s new Central Committee, the Politburo, and its Standing Committee.

The 20th Party Congress has concluded and China’s new leadership for the next five years has been revealed. All of the new full and alternate members of the 20th Central Committee were announced on October 22 and a day later, on October 23rd, the new seven-member Politburo Standing Committee was unveiled.

As was widely expected, Xi Jinping will continue his third five-year term as leader.

The lists with new member names went trending on Chinese social media. On Weibo alone, the hashtag “20th Central Committee Members List” (#二十届中央委员会委员名单#) received a staggering 580 million clicks within two days time. There were also other trending hashtags during the weekend of the closing session of the 20th Party Congress, such as “The Resumes of the New Politburo Standing Committee Members” (#新一届中央政治局常委简历#).

The Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党中央委员会) is, theoretically, the highest authority within the Party pyramid, and its members (generally 170-205 full members) are nominally elected every five years by the National Party Congress. It is the primary authority of the Central Committee to elect the Politburo (中国共产党中央政治局), which actually is the top decision-making body in the Party (21-25 members).

Among the members of the Politburo are those of the Standing Committee (中国共产党中央政治局常务委员会), which basically is the core leadership of the Party (generally 5-11 members, including the Party General Secretary). This is the list of names that everyone has been mostly waiting to see this week.

Here, we will list the member names of China’s new 20th Central Committee, the Politburo, and its Standing Committee. We have put them in alphabetical order, based on the first letter of their written in pinyin, and have included all names in characters.

The 20th Central Committee (Full Members)

Noteworthy:

– The 19th Central Committee was composed of 204 full members (among them only 10 women), this 20th Central Committee list contains 205 full members and 11 of them are women.

– Nine of these members come from a minority ethnic group, including one Uyghur.

– Premier Li Keqiang and the head of the National People’s Congress, Li Zhanshu, the second- and third-highest ranking officials in the party, have not been included, neither have Wang Yang, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference chairman and Vice-Premier Han Zheng.

Abbreviations:

– CMC = Central Military Commission

– CPC = Communist Party of China

– CSSC = China State Shipbuilding Corporation

– PLA = People’s Liberation Army

(The 171 alternate members of the 20th Central Committee, who do not have voting rights, have not been listed here).

1. Bate’er 巴特尔 (Mongolian) (Vice Chairperson of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference)

2. Cai Jianjiang 蔡剑江 (Director of the Office of the Central Air Traffic Management Commission)

3. Cai Qi 蔡奇 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, Party Secretary of Beijing)

4. Chang Dingqiu 常丁求 (PLA General, Commander of PLA Air Force)

5. Chen Gang 陈刚 (Party Secretary of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions)

6. Chen Jining 陈吉宁 (New Politburo member, Deputy Party Secretary, Mayor of Beijing)

7. Chen Min’er 陈敏尔 (18th-20th Politburo member, Party Chief of Chongqing)

8. Chen Wenqing 陈文清 (New Politburo member, Ministry of State Security Minister, Party Secretary)

9. Chen Xiaojiang 陈小江 (Executive Deputy Head of the United Front Work Department of the CPC Central Committee)

10. Chen Xu 陈旭 (female) (Deputy Head of the CPC United Front Work Department, Director of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office)

11. Chen Yixin 陈一新 (Secretary-General of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission)

12. Cheng Lihua 程丽华 (female) (Deputy Secretary of Anhui Provincial Party Committee)

13. Ding Xuedong 丁学东 (Deputy Secretary-General of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China)

14. Ding Xuexiang 丁薛祥 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, a senior aide to Xi Jinping)

15. Dong Jun 董军 (PLA Admiral, Commander of the People’s Liberation Army Navy)

16. Erkin Tuniyaz 艾尔肯·吐尼亚孜 (Uyghur) (Chairman of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region)

17. Feng Fei 冯飞 (Governor of Hainan)

18. Fu Hua 傅华 (President of Xinhua News Agency)

19. Gao Xiang 高翔 (Vice President, Deputy Secretary of the Party core group of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences)

20. Gao Zhidan 高志丹 (Director of the State General Administration of Sports)

21. Gong Zheng 龚正 (Mayor and Deputy Communist Party Secretary of Shanghai Municipality)

22. Guo Puzheng 郭普校 (Political Commissar to the PLA Air Force)

23. Han Jun 韩俊 (Governor of Jilin Province)

24. Han Wenxiu 韩文秀 (Deputy Director, Research Office of the State Council)

25. Hao Peng 郝鹏 (Chairman and Party Committee Secretary of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission)

26. He Hongjun 何宏军 (PLA Lieutenant General)

27. He Junke 贺军科 (First Secretary of the Communist Youth League of China)

28. He Lifeng 何立峰 (New Politburo member, head of the National Development and Reform Commission)

29. He Rong (female) 贺荣 (Deputy Chief Justice, Executive Vice president of the Supreme People’s Court of China)

30. He Weidong 何卫东 (New Politburo member, Commander of the CMC’s Joint Command Centre)

31. Hou Jianguo 侯建国 (former President of the University of Science and Technology of China)

32. Hou Kai 侯凯 (Member of Standing Committee of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, Auditor General of the National Audit Office)

33. Hu Changsheng 胡昌升 (Governor of Heilongjiang)

34. Hu Chunhua 胡春华 (former Politburo member, Vice Premier of the People’s Republic of China)

35. Hu Henghua 胡衡华 (Deputy Party Secretary and Mayor of Chongqing)

36. Hu Heping 胡和平 (Party Secretary of Ministry of Culture and Tourism)

37. Hu Yuting 胡玉亭 (Deputy Secretary of the Liaoning Provincial Committee)

38. Hu Zhongming 胡中明 (PLA Vice Admiral, Chief of Staff of the PLA Navy)

39. Huai Jinpeng 怀进鹏 (Party Secretary of the China Association for Science and Technology)

40. Huang Jianfa 黄建发 (Deputy Secretary of the Zhejiang Provincial Party Committee)

41. Huang Kunming 黄坤明 (19th/20th Politburo member, head of the CPC Publicity Department)

42. Huang Ming 黄铭 (PLA Lieutenant General, Chief of Staff of the PLA)

43. Huang Qiang 黄强 (Governor of Sichuan Province)

44. Huang Shouhong 黄守宏 (Director of the State Council Research Office)

45. Huang Xiaowei 黄晓薇 (female) (Party Decretary of the All-China Women’s Federation)

46. Jin Xiangjun 金湘军 (Deputy Mayor of Tianjin)

47. Jin Zhuanglong 金壮龙 (Minister of Industry and Information Technology)

48. Jing Junhai 景俊海 (Governor of Jilin)

49. Ju Qiansheng 巨乾生 (PLA General, Commander of the PLA Strategic Support Force)

50. Lan Fo’an 蓝佛安 (Governor of Shanxi)

51. Lan Tianli 蓝天立 (Zhuang ethnic group) (Chairman, Deputy Party Chief of Guangxi)

52. Lei Fanpei 雷凡培 (former Party Secretary, Chairman of CSSC)

53. Li Bingjun 李炳军 (Governor of Guizhou Province)

54. Li Fengbiao 李凤彪 (PLA General, Political commissar of the Western Theater Command)

55. Li Ganjie 李干杰 (New Politburo member, Party Secretary of Shandong)

56. Li Guoying 李国英 (Governor of Anhui province)

57. Li Hongzhong 李鸿忠 (also 19th/20th Politburo member, Tianjin Party Secretary)

58. Li Lecheng 李乐成 (Governor of Liaoning)

59. Li Qiang 李强 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, 19th/20th Politburo member and Party Secretary of Shanghai)

60. Li Qiaoming 李桥铭 (PLA General, former commander of the Northern Theater Command)

61. Li Shangfu 李尚福 (PLA General, Head of the Equipment Development Department of the Central Military Commission)

62. Li Shulei 李书磊 (New Politburo member, Executive Deputy Head of the Publicity Department)

63. Li Wei 李伟 (former Director of the Development Research Center of the State Council)

64. Li Xi 李希 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, 19th/20th Politburo member and Party Secretary of Guangdong, Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection)

65. Li Xiaohong 李晓红 (President of the Chinese Academy of Engineering)

66. Li Xiaoxin 李小新 (female) (Vice Minister of the Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee (ODCPC)

67. Li Yi 李屹 (Party branch Secretary, Vice president of China Federation of Literary and Art Circles)

68. Li Yifei 李邑飞 (Deputy Secretary of the Party Committee of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region)

69. Li Yuchao 李玉超 (PLA General, Commander of PLA Rocket Force)

70. Liang Huiling 梁惠玲 (female) (Chair of the All-China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives)

71. Liang Yanshun 梁言顺 (Party Secretary of Ningxia)

72. Lin Wu 林武 (Party Secretary of Shanxi)

73. Lin Xiangyang 林向阳 (PLA General, Commander of Eastern Theater Command)

74. Liu Faqing 刘发庆 (PLA Lieutenant General, Secretary-General of National Defense Mobilization Commission)

75. Liu Guozhong 刘国中 (New Politburo Member, Party Secretary of Shaanxi)

76. Liu Haixing 刘海星 (Deputy Director in the Office of the National Security Commission)

77. Liu Jianchao 刘建超 (Director of the International Liaison Department of the CPC)

78. Liu Jinguo 刘金国 (Deputy Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection)

79. Liu Junchen 刘俊臣 (Deputy Secretary of Party Organs Working Committee)

80. Liu Ning 刘宁 (Party Secretary of Guangxi)

81. Liu Qingsong 刘青松 (PLA Admiral, Political Commissar of the Northern Theater Command)

82. Liu Wei 刘伟 (Chairman of the CPPCC Henan Committee)

83. Liu Xiaoming 刘小明 (former Ambassador of China to the United Kingdom)

84. Liu Zhenli 刘振立 (PLA General, Commander of the PLA Ground Force)

85. Lou Yangsheng 楼阳生 (Party Secretary of Henan Province)

86. Lu Hao 陆昊 (Party Branch Secretary of Development Research Center of the State Council)

87. Lu Zhiyuan 陆治原 (Deputy Secretary of Shandong Provincial Committee, Secretary of Qingdao Municipal Committee)

88. Luo Wen 罗文 (Head of China’s State General Administration for Market Regulation)

89. Ma Xiaowei马晓伟 (National Health Commission Director, Vice President of the Red Cross Society of China)

90. Ma Xingrui 马兴瑞 (New Politburo member, Xinjiang Party Secretary, former Guangdong governor)

91. Mao Weiming 毛伟明 (Governor of Hunan Province)

92. Meng Fanli 孟凡利 (Party Secretary of Shenzhen, Deputy Party Secretary of Guangdong)

93. Meng Xiangfeng 孟祥锋 (Executive Deputy Director of the General Office of CPC)

94. Miao Hua 苗华 (19th/20th CC, Admiral of the Chinese PLA Navy, Director of Political Work Department of Central Military Commission)

95. Ni Hong 倪虹 (Minister of Housing and Urban-Rural Development)

96. Ni Yuefeng 倪岳 峰 (Party Secretary of Hebei)

97. Nurlan Abelmanjen 努尔兰·阿不都满金 (Kazakh) (Chairman of the Xinjiang Regional Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference)

98. Pan Yue 潘岳 (Minister of the State Ethnic Affairs Commission)

99. Pei Jinjia 裴金佳 (Minister of Veterans Affairs)

100. Qi Yu 齐玉 (Secretary of the CPC Committee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

101. Qin Gang 秦刚 (Chinese Ambassador to the United States)

102. Qin Shutong 秦树桐 (PLA General, Political Commissar of the PLA Ground Force)

103. Qu Qingshan 曲青山 (President of the Institute of Party History and Literature of the Central Committee of CPC)

104. Ren Zhenhe 任振鹤 (Tujia ethnic group) (Governor of Gansu Province)

105. Shen Chunyao 沈春耀 (Chairperson of the Legislative Affairs Committee of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress)

106. Shen Haixiong 慎海雄 (Propaganda Chief of Guangdong Province)

107. Shen Xiaoming 沈晓明 (former Governor of Hainan)

108. Shen Yiqing 谌贻琴 (female, Bai ethnic group) (Communist Party Secretary of Guizhou)

109. Shen Yueyue 沈跃跃 (female) (President of the All-China Women’s Federation)

110. Shi Taifeng 石泰峰 (New Politburo member, President of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences)

111. Sun Jinlong 孙金龙 (Party Branch Secretary of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps)

112. Sun Shaocheng 孙绍骋 (Party Secretary of Inner Mongolia)

113. Tang Dengjie 唐登杰 (Minister of Civil Affairs)

114. Tang Renjian 唐仁健 (Governor of Gansu Province)

115. Tie Ning 铁凝 (female) (President of the China Writers Association)

116. Tong Jianming 童建明 (Grand Prosecutor and first Deputy Prosecutor General of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate)

117. Tuo Zhen 庹震 (President of the People’s Daily)

118. Wan Lijun 万立骏 (researcher, former President of the University of Science and Technology of China)

119. Wang Chunning 王春宁 (PLA General, Commander of the People’s Armed Police)

120. Wang Dongming 王东明 (Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee, Chairman of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions)

121. Wang Guanghua 王广华 (Minister of Natural Resources)

122. Wang Haijiang (PLA General, Commander of Western Theater Command)

123. Wang Hao 王浩 (Governor of Zhejiang)

124. Wang Huning 王沪宁 (Politburo Standing Committee since 2017, 19th/20th Politburo member, First Secretary of the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party)

125. Wang Junzheng 王君正 (Communist Party Secretary of Tibet)

126. Wang Kai 王凯 (Governor of Henan Province)

127. Wang Kai 王凯 (Lieutenant General of the PLA)

128. Wang Lixia 王莉霞 (female, Mongolian) (Deputy Party Chief, Party branch Secretary, Chairwoman of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region)

129. Wang Menghui 王蒙徽 (Communist Party Secretary of Hubei)

130. Wang Ning 王宁 (Party Secretary of Yunnan)

131. Wang Peng 王鹏 (Vice President and Chief of Education of the People’s Liberation Army National Defence University)

132. Wang Qiang 王强 (PLA General, Commander of the North Sea Fleet)

133. Wang Qingxian 王清宪 (Governor of Anhui)

134. Wang Renhua 王仁华 (Vice Admiral of the PLA, Secretary of the Political and Legal Affairs Commission of the Central Military Commission)

135. Wang Shouwen 王受文 (China International Trade Representative, Vice Minister of Commerce)

136. Wang Weizhong 王伟中 (Deputy Party Secretary, Governor of Guangdong)

137. Wang Wenquan 王文全 (Political Commissar of the Joint Logistics Support Unit of the Central Military Commission)

138. Wang Wentao 王文涛 (Minister of Commerce)

139. Wang Xiangxi 王祥喜 (Minister of Emergency Management)

140. Wang Xiaohong 王小洪 (Party Secretary, Minister of Public Security)

141. Wang Xiaohui 王晓晖 (Party Secretary of Sichuan)

142. Wang Xiubin 王秀斌 (PLA General, Commander of the Southern Theater Command)

143. Wang Yi 王毅 (New Politburo member, State Councillor and Foreign Minister)

144. Wang Yong 王勇 (Chinese State Councilor)

145. Wang Yubo 王予波 (Governor of Yunnan Province)

146. Wang Zhengpu 王正谱 (Governor of Hebei)

147. Wang Zhijun 王志军 (Vice Minister of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology)

148. Wang Zhonglin 王忠林 (Governor of Hubei)

149. Wu Hansheng 吴汉圣 (Deputy Secretary of Work Committee of Central Government in charge of Daily Work)

150. Wu Xiaojun 吴晓军 (Governor of Qinghai)

151. Wu Yanan 吴亚男 (General of the PLA, Commander of the Central Theater Command)

152. Wu Zhenglong 吴政隆 (Secretary of Jiangsu)

153. Xi Jinping 习近平 (General Secretary of the Party, President PRC, Chairman of the Central Military Commission)

154. Xiao Jie 肖捷 (State Councilor, Secretary General of the State Council)

155. Xiao Pei 肖培 (Deputy Secretary of the CPC Committee for Discipline and Inspection)

156. Xie Chuntao 谢春涛 (Vice President of the Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party)

157. Xin Changxing 信长星 (Party Secretary of Qinghai)

158. Xu Deqing 徐德清 (General of PLA, Political Commissar of the Central Theater Command)

159. Xu Kunlin 许昆林 (Governor of Jiangsu)

160. Xu Lin 徐麟 (Director of the National Radio and Television Administration)

161. Xu Qiling 徐起零 (General of the PLA)

162. Xu Qin 许勤 (Former Governor of Hebei)

163. Xu Xisheng 徐西盛 (Political Commissar of Southern Theater Command Air Force)

164. Xu Xueqiang 许学强 (General of the PLA, President of PLA National Defence University)

165. Xu Zhongbo 徐忠波 (PLA General, Political Commissar of PLA Army Rocket Force)

166. Yan Jinhai (Tibetan) (Chairman of Tibet Autonomous Region)

167. Yang Cheng 杨诚 (Lieutenant General of the PLA, Political Commissar of the Xinjiang Military District)

168. Yang Xuejun 杨学军 (President of the PLA Academy of Military Science)

169. Yang Zhiliang 杨志亮 (Vice Admiral of the PLA Navy, Political Commissar of the South Sea Fleet)

170. Ye Jianchun 叶建春 (Governor of Jiangxi)

171. Yi Huiman 易会满 (Head of the China Securities and Regulatory Commission)

172. Yi Lianhong 易炼红 (Party Secretary of Jiangxi)

173. Yin Hejun 阴和俊 (Deputy Secretary of the Party Committee of the Chinese Academy of Sciences)

174. Yin Hong 尹弘 (former Governor of Henan Province)

175. Yin Li 尹力 (New Politburo member / Communist Party Secretary of Fujian)

176. Yin Yong 殷勇 (Deputy Prosecutor-General of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate)

177. Ying Yong (deputy party chief of the municipality of Beijing and a former deputy governor of the People’s Bank of China)

178. Yu Jianhua 俞建华 (Head of the General Administration of Customs)

179. Yu Qingjiang 俞庆江 (Lieutenant General of the PLA Air Force, Chief of Staff of PLA)

180. Yuan Huazhi 袁华智 (Admiral and Political Commissar of the PLA)

181. Yuan Jiajun 袁家军 (New Politburo member, Zhejiang Party Secretary)

182. Zhang Gong 张工 (Mayor of Tianjin)

183. Zhang Guoqing 张国清 (New Politburo member, Party Secretary of Liaoning)

184. Zhang Hongbing 张红兵 (PLA Political Commissar)

185. Zhang Hongsen 张宏森 (Party Branch Secretary of China Writers Association)

186. Zhang Jun 张军 (Procurator-General of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate)

187. Zhang Lin 张林 (Head of the Logistic Support Department of the Central Military Commission)

188. Zhang Qingwei 张庆伟 (Secretary of Hunan, former Governor of Hebei)

189. Zhang Shengmin 张升民 (Secretary of the Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Central Military Commission of PLA)

190. Zhang Youxia 张又侠 (19th/20th Politburo member, General in the PLA, second-ranked Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission)

191. Zhang Yupu 张雨浦 (Hui) (Chairman of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region)

192. Zhang Yuzhuo 张玉卓 (Party branch secretary of the China Association for Science and Technology)

193. Zhao Gang 赵刚 (Member Standing Committee of Zaozhuang Municipal Committee)

194. Zhao Leji 赵乐际 (Politburo member since 2012, secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, former Head of the CPC Organization Department)

195. Zhao Long 赵龙 (Governor of Fujian)

196. Zhao Xiaozhe 赵晓哲 (Vice Admiral of PLA and Director of Science and Technology Committee of the Central Military Commission)

197. Zhao Yide 赵一德 (Governor of Shaanxi, former Governor/Deputy Secretary of Hebei)

198. Zheng Shanjie 郑栅洁 (Governor/Deputy Party Secretary of Zhejiang and Party Secretary of Ningbo)

199. Zheng Xincong 郑新聪 (Director of Liaison Office in Macau, former Deputy Governor Fujian)

200. Zhong Shaojun 钟绍军 (aide of Xi Jinping, Director of the General Office of the Central Military Commission of People’s Liberation Army)

201. Zhou Naixiang 周乃翔 (Governor of Shandong)

202. Zhou Qiang 周强 (Chief Justice and President of the Supreme People’s Court of China)

203. Zhou Zuyi 周祖翼 (Minister of Human Resources and Social Security)

204. Zhuang Rongwen 庄荣文 (Director of the Cyberspace Administration of China)

205. Zou Jiayi 邹加怡 (female) (Vice Minister of the Ministry of Finance)

20th Politburo Members

Noteworthy:

– For the first time in 25 years, there are no female members in this list.

1. Cai Qi 蔡奇 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, Party Secretary of Beijing)

2. Chen Jining 陈吉宁 (New Politburo member, Deputy Party Secretary and mayor of Beijing)

3. Chen Min’er 陈敏尔 (18th-20th Politburo member and party chief of Chongqing)

4. Chen Wenqing 陈文清 (New Politburo member, Ministry of State Security Minister&Party Secretary)

5. Ding Xuexiang 丁薛祥 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, a senior aide to Xi Jinping)

6. He Lifeng 何立峰 (New Politburo member, head of the National Development and Reform Commission)

7. He Weidong 何卫东 (New Politburo member, Commander of the CMC’s Joint Command Centre)

8. Huang Kunming 黄坤明 (19th/20th Politburo member, head of the CPC Publicity Department)

9. Li Ganjie 李干杰 (New Politburo member, Party Secretary of Shandong)

10. Li Hongzhong 李鸿忠 (also 19th/20th Politburo member, Tianjin Party Secretary)

11. Li Qiang 李强 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, 19th/20th Politburo member and Party Secretary of Shanghai)

12. Li Shulei 李书磊 (New Politburo member, Executive Deputy Head of the Publicity Department)

13. Li Xi 李希 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, 19th/20th Politburo member and Party Secretary of Guangdong, Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection)

14. Liu Guozhong 刘国中 (New Politburo Member, Party Secretary of Shaanxi)

15. Ma Xingrui 马兴瑞 (New Politburo member, Xinjiang Party Secretary, former Guangdong governor)

16. Shi Taifeng 石泰峰 (New Politburo member, President of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences)

17. Wang Huning 王沪宁 (Politburo Standing Committee since 2017, 19th/20th Politburo member, First Secretary of the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party)

18. Wang Yi 王毅 (New Politburo member, State Councillor and Foreign Minister)

19. Xi Jinping 习近平 (General Secretary of the Party, President PRC, Chairman of the Central Military Commission)

20. Yin Li 尹力 (New Politburo member, Party Secretary of Fujian)

21. Yuan Jiajun 袁家军 (New Politburo member, Zhejiang Party Secretary)

22. Zhang Guoqing 张国清 (New Politburo member, Party Secretary of Liaoning)

23. Zhang Youxia 张又侠 (19th/20th Politburo member, General in the PLA, second-ranked Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission)

24. Zhao Leji 赵乐际 (Politburo member since 2012, secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, former Head of the CPC Organization Department)

20th Politburo Standing Committee

Noteworthy:

– Four of the members are new to the Standing Committee.

– Li Keqiang, Wang Yang, Wang Qishan, and Li Zhanshu are gone from the Standing Committee.

– No female members – there never have been in the Standing Committee.

1. Cai Qi 蔡奇 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, Party Secretary of Beijing)

2. Ding Xuexiang 丁薛祥 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, a senior aide to Xi Jinping)

3. Li Qiang 李强 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, 19th/20th Politburo member and Party Secretary of Shanghai)

4. Li Xi 李希 (New Politburo Standing Committee member, 19th/20th Politburo member and Party Secretary of Guangdong, Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection)

5. Xi Jinping 习近平 (General Secretary of the Party, President PRC, Chairman of the Central Military Commission)

6. Wang Huning 王沪宁 (Politburo Standing Committee since 2017, 19th/20th Politburo member, First Secretary of the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party)

7. Zhao Leji 赵乐际 (Politburo member since 2012, secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, former Head of the CPC Organization Department)

For more about the Party Congress, check our other articles here.

If you appreciate the work we do, please subscribe to What’s on Weibo to support us

By Manya Koetse

Sources (other sources linked to inside text)

Reuters. 2022. “Factbox: China’s new elite Communist Party leadership.” Reuters, Oct 23 https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-new-elite-communist-party-leadership-2022-10-23/ [Oct 23 2022].

Sullivan, Lawrence R. 2012. Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Communist Party. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press. See page: 3-43, 208.

Saich, Tony. 2004. Governance and Politics of China. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. See page: 97.

Image of Chinese Flag

Photo by Alejandro Luengo on Unsplash

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Insight

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

The story of ‘Fat Cat’ has become a hot topic in China, sparking widespread sympathy and discussions online.

Published

3 months agoon

May 9, 2024

The tragic story behind the recent suicide of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ has become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media, touching upon broader societal issues from unfair gender dynamics to businesses taking advantage of grieving internet users.

The story of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer from Hunan who committed suicide has gone completely viral on Weibo and beyond this week, generating many discussions.

In late April of this year, the young man nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ (胖猫 Pàng Māo, literally fat or chubby cat), tragically ended his life by jumping into the river near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge (重庆长江大桥) following a breakup with his girlfriend. By now, the incident has come to be known as the “Fat Cat Jumping Into the River Incident” (胖猫跳江事件).

News of his suicide soon made its rounds on the internet, and some bloggers started looking into what was behind the story. The man’s sister also spoke out through online channels, and numerous chat records between the young man and his girlfriend emerged online.

One aspect of his story that gained traction in early May is the revelation that the man had invested all his resources into the relationship. Allegedly, he made significant financial sacrifices, giving his girlfriend over 510,000 RMB (approximately 71,000 USD) throughout their relationship, in a time frame of two years.

When his girlfriend ended the relationship, despite all of his efforts, he was devastated and took his own life.

The story was picked up by various Chinese media outlets, and prominent social and political commentator Hu Xijin also wrote a post about Fat Cat, stating the sad story had made him tear up.

As the news spread, it sparked a multitude of hashtags on Weibo, with thousands of netizens pouring out their thoughts and emotions in response to the story.

Playing Games for Love

The main part of this story that is triggering online discussions is how ‘Fat Cat,’ a young man who possessed virtually nothing, managed to provide his girlfriend, who was six years older, with such a significant amount of money – and why he was willing to sacrifice so much in order to do so.

The young man reportedly was able to make money by playing video games, specifically by being a so-called ‘booster’ by playing with others and helping them get to a higher level in multiplayer online battle games.

According to his sister, he started working as a ‘professional’ video gamer as a means of generating money to satisfy his girlfriend, who allegedly always demanded more.

He registered a total of 36 accounts to receive orders to play online games, making 20 yuan per game (about $2.80). Because this consumed all of his time, he barely went out anymore and his social life was dead.

In order to save more money, he tried to keep his own expenses as low as possible, and would only get takeout food for himself for no more than 10 yuan ($1,4). His online avatar was an image of a cat saying “I don’t want to eat vegetables, I want to eat McDonald’s.”

The woman in question who he made so many sacrifices for is named Tan Zhu (谭竹), and she soon became the topic of public scrutiny. In one screenshot of a chat conversation between Tan and her boyfriend that leaked online, she claimed she needed money for various things. The two had agreed to get married later in this year.

Despite of this, she still broke up with him, driving him to jump off the bridge after transferring his remaining 66,000 RMB (9135 USD) to Tan Zhu.

As the story fermented online, Tan Zhu also shared her side of the story. She claimed that she had met ‘Fat Cat’ over two years ago through online gaming and had started a long distance relationship with him. They had actually only met up twice before he moved to Chongqing. She emphasized that financial gain was never a motivating factor in their relationship.

Tan additionally asserted that she had previously repaid 130,000 RMB (18,000 USD) to him and that they had reached a settlement agreement shortly before his tragic death.

Ordering Take-Out to Mourn Fat Cat

– “I hope you rest in peace.”

– “Little fat cat, I hope you’ll be less foolish in your next life.”

– “In your next life, love yourself first.”

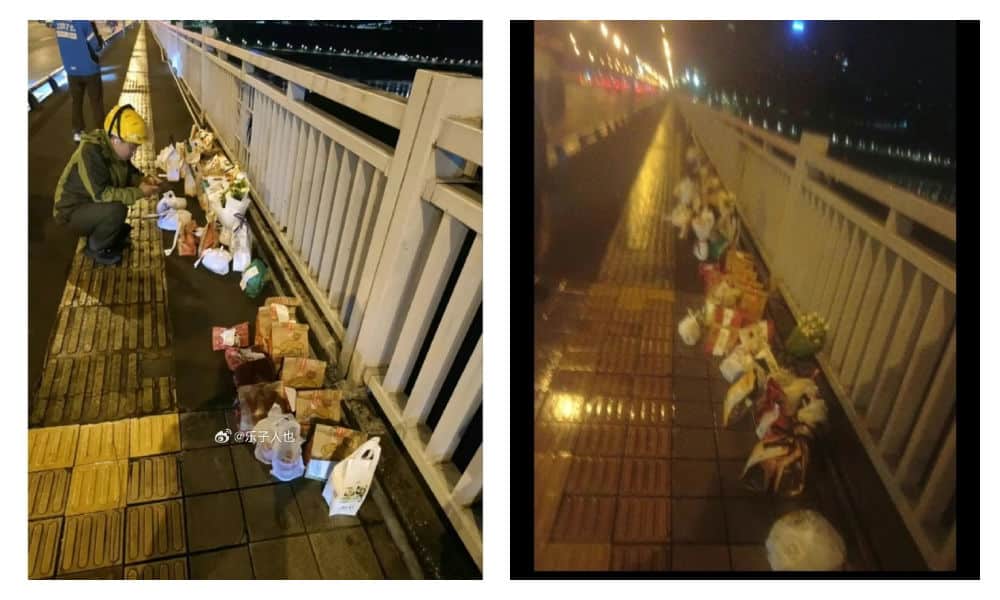

These are just a few of the messages left by netizens on notes attached to takeout food deliveries near the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge.

AI-generated image spread on Chinese social media in connection to the event.

As Fat Cat’s story stirred up significant online discussion, with many expressing sympathy for the young man who rarely indulged in spending on food and drinks, some internet users took the step of ordering McDonalds and other food delivery services to the bridge, where he tragically jumped from, in his honor.

This soon snowballed into more people ordering food and drinks to the bridge, resulting in a constant flow of delivery staff and a pile-up of take-out bags.

Delivery food on the bridge, photo via Weibo.

However, as the food delivery efforts picked up pace, it came to light that some of the deliveries ordered and paid for were either empty or contained something different; certain restaurants, aware of the collective effort to honor the young man, deliberately left the food boxes empty or substituted sodas or tea with tap water.

At least five restaurants were caught not delivering the actual orders. Chinese bubble tea shop ChaPanda was exposed for substituting water for milk tea in their cups. On May 3rd, ChaPanda responded that they had fired the responsible employee.

Another store, the Zhu Xiaoxiao Luosifen (朱小小螺蛳粉), responded on that they had temporarily closed the shop in question to deal with the issue. Chinese fast food chain NewYobo (牛约堡) also acknowledged that at least twenty orders they received were incomplete.

Fast food company Wallace (华莱士) responded to the controversy by stating they had dismissed the employees involved. Mixue Ice Cream & Tea (蜜雪冰城) issued an apology and temporarily closed one of their stores implicated in delivering empty orders.

In the midst of all the controversy, Fat Cat’s sister asked internet users to refrain from ordering take-out food as a means of mourning and honoring her brother.

Nevertheless, take-out food and flowers continued to accumulate near the bridge, prompting local authorities to think of ways of how to deal with this unique method of honoring the deceased gamer.

Gamer Boy Meets Girl

On Chinese social media, this story has also become a topic of debate in the context of gender dynamics and social inequality.

There are some male bloggers who are angry with Tan Zhu, suggesting her behaviour is an example of everything that’s supposedly “wrong” with Chinese women in this day and age.

Others place blame on Fat Cat for believing that he could buy love and maintain a relationship through financial means. This irked some feminist bloggers, who see it as a chauvinistic attitude towards women.

A main, recurring idea in these discussions is that young Chinese men such as Fat Cat, who are at the low end of the social ladder, are actually particularly vulnerable in a fiercely competitive society. Here, a gender imbalance and surplus of unmarried men make it easier for women to potentially exploit those desperate for companionship.

The story of Fat Cat brings back memories of ‘Mo Cha Official,’ a not-so-famous blogger who gained posthumous fame in 2021 when details of his unhappy life surfaced online.

Likewise, the tragic tale of WePhone founder Su Xiangmao (苏享茂) resurfaces. In 2017, the 37-year-old IT entrepreneur from Beijing took his own life, leaving behind a note alleging blackmail by his 29-year-old ex-wife, who demanded 10 million RMB (±1.5 million USD) (read story).

Another aspect of this viral story that is mentioned by netizens is how it gained so much attention during the Chinese May holidays, coinciding with the tragic news of the southern China highway collapse in Guangdong. That major incident resulted in the deaths of at least 48 people, and triggered questions over road safety and flawed construction designs. Some speculate that the prominence given to the Fat Cat story on trending topic lists may have been a deliberate attempt to divert attention away from this incident.

‘Fat Cat’ was cremated. His family stated their intention to take necessary legal steps to recover the money from his former girlfriend, but Tan Zhu reportedly already reached an agreement with the father and settled the case. Nevertheless, the case continues to generate discussions online, with some people wondering: “Is it over yet? Can we talk about something different now?”

Fat Cat images projected in Times Square

However, given that images of the ‘Fat Cat’ avatar have even appeared in Times Square in New York by now (Chinese internet users projected it on one of the big LED screens), it’s likely that this story will be remembered and talked about for some time to come.

UPDATE MAY 25

On May 20, local authorities issued a lengthy report to clarify the timeline of events and details surrounding the death of “Fat Cat,” which had attracted significant attention across China.

The report concluded that there was no fraud involved and that “Fat Cat” and his girlfriend were in a genuine relationship. Tan did not deceive “Fat Cat” for money; the transfers were voluntary. Furthermore, Tan returned most of the money to his parents.

The gamer’s sister is reportedly still being investigated for potentially infringing on Tan’s privacy by disclosing numerous private details to the public.

In the end, one thing is clear in this gamer’s tragic story, which is that there are no winners.

By Manya Koetse

– With contributions by Miranda Barnes and Ruixin Zhang

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy.

Published

3 months agoon

May 3, 2024

It seemed like such a good idea. For this year’s World Book Day, Chinese tea brand LELECHA (乐乐茶) put a spotlight on Lu Xun (鲁迅, 1881-1936), one of the most celebrated Chinese authors the 20th century and turned him into the the ‘brand ambassador’ of their special new “Smoky Oolong” (烟腔乌龙) milk tea.

LELECHA is a Chinese chain specializing in new-style tea beverages, including bubble tea and fruit tea. It debuted in Shanghai in 2016, and since then, it has expanded rapidly, opening dozens of new stores not only in Shanghai but also in other major cities across China.

Starting on April 23, not only did the LELECHA ‘Smoky Oolong” paper cups feature Lu Xun’s portrait, but also other promotional materials by LELECHA, such as menus and paper bags, accompanied by the slogan: “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” (“老烟腔,新青年”). The marketing campaign was a joint collaboration between LELECHA and publishing house Yilin Press.

Lu Xun featured on LELECHA products, image via Netease.

The slogan “Old Smoky Oolong, New Youth” is a play on the Chinese magazine ‘New Youth’ or ‘La Jeunesse’ (新青年), the influential literary magazine in which Lu’s famous short story, “Diary of a Madman,” was published in 1918.

The design of the tea featuring Lu Xun’s image, its colors, and painting style also pay homage to the era in which Lu Xun rose to prominence.

Lu Xun (pen name of Zhou Shuren) was a leading figure within China’s May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement (1915-24) is also referred to as the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance. It was the cultural revolution brought about by the political demonstrations on the fourth of May 1919 when citizens and students in Beijing paraded the streets to protest decisions made at the post-World War I Versailles Conference and called for the destruction of traditional culture[1].

In this historical context, Lu Xun emerged as a significant cultural figure, renowned for his critical and enlightened perspectives on Chinese society.

To this day, Lu Xun remains a highly respected figure. In the post-Mao era, some critics felt that Lu Xun was actually revered a bit too much, and called for efforts to ‘demystify’ him. In 1979, for example, writer Mao Dun called for a halt to the movement to turn Lu Xun into “a god-like figure”[2].

Perhaps LELECHA’s marketing team figured they could not go wrong by creating a milk tea product around China’s beloved Lu Xun. But for various reasons, the marketing campaign backfired, landing LELECHA in hot water. The topic went trending on Chinese social media, where many criticized the tea company.

Commodification of ‘Marxist’ Lu Xun

The first issue with LELECHA’s Lu Xun campaign is a legal one. It seems the tea chain used Lu Xun’s portrait without permission. Zhou Lingfei, Lu Xun’s great-grandson and president of the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation, quickly demanded an end to the unauthorized use of Lu Xun’s image on tea cups and other merchandise. He even hired a law firm to take legal action against the campaign.

Others noted that the image of Lu Xun that was used by LELECHA resembled a famous painting of Lu Xun by Yang Zhiguang (杨之光), potentially also infringing on Yang’s copyright.

But there are more reasons why people online are upset about the Lu Xun x LELECHA marketing campaign. One is how the use of the word “smoky” is seen as disrespectful towards Lu Xun. Lu Xun was known for his heavy smoking, which ultimately contributed to his early death.

It’s also ironic that Lu Xun, widely seen as a Marxist, is being used as a ‘brand ambassador’ for a commercial tea brand. This exploits Lu Xun’s image for profit, turning his legacy into a commodity with the ‘smoky oolong’ tea and related merchandise.

“Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you in an article. ”

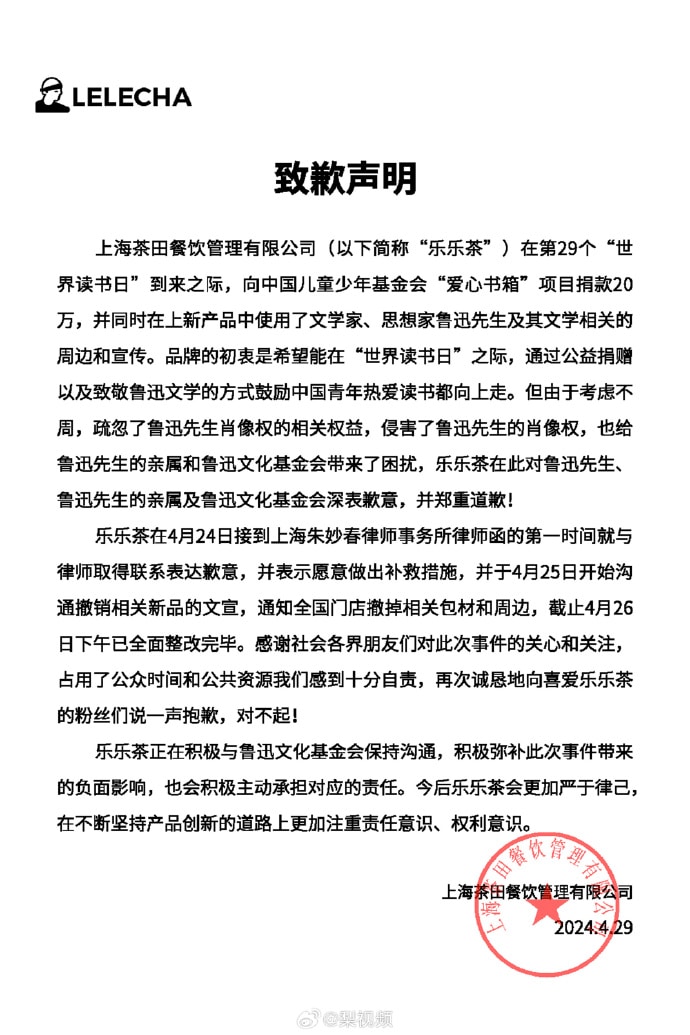

On April 29, LELECHA finally issued an apology to Lu Xun’s relatives and the Lu Xun Cultural Foundation for neglecting the legal aspects of their marketing campaign. They claimed it was meant to promote reading among China’s youth. All Lu Xun materials have now been removed from LELECHA’s stores.

Statement by LELECHA.

On Chinese social media, where the hot tea became a hot potato, opinions on the issue are divided. While many netizens think it is unacceptable to infringe on Lu Xun’s portrait rights like that, there are others who appreciate the merchandise.

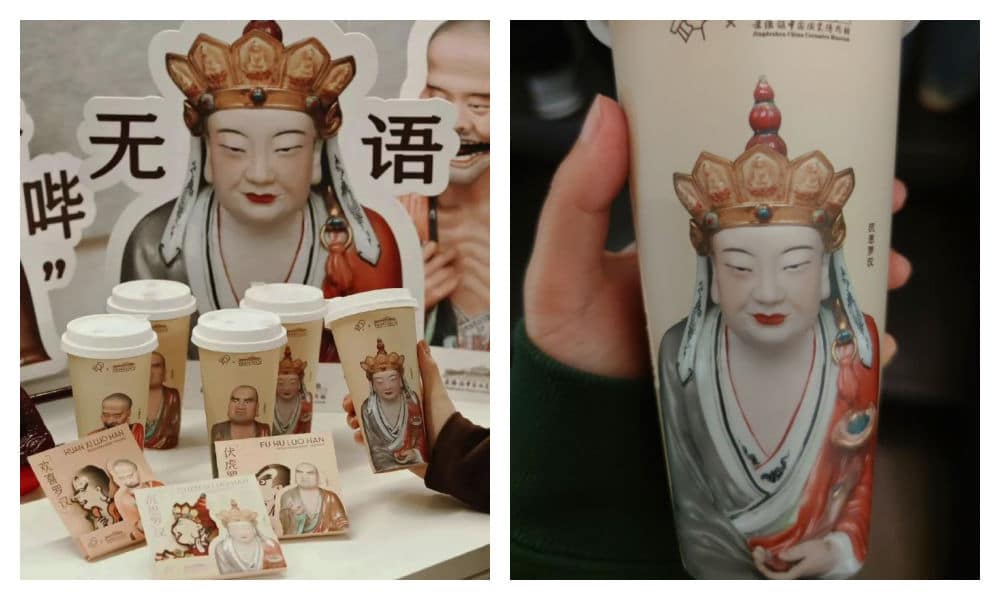

The LELECHA controversy is similar to another issue that went trending in late 2023, when the well-known Chinese tea chain HeyTea (喜茶) collaborated with the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum to release a special ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ (佛喜) latte tea series adorned with Buddha images on the cups, along with other merchandise such as stickers and magnets. The series featured three customized “Buddha’s Happiness” cups modeled on the “Speechless Bodhisattva” (无语菩萨), which soon became popular among netizens.

The HeyTea Buddha latte series, including merchandise, was pulled from shelves just three days after its launch.

However, the ‘Buddha’s Happiness’ success came to an abrupt halt when the Ethnic and Religious Affairs Bureau of Shenzhen intervened, citing regulations that prohibit commercial promotion of religion. HeyTea wasted no time challenging the objections made by the Bureau and promptly removed the tea series and all related merchandise from its stores, just three days after its initial launch.

Following the Happy Buddha and Lu Xun milk tea controversies, Chinese tea brands are bound to be more careful in the future when it comes to their collaborative marketing campaigns and whether or not they’re crossing any boundaries.

Some people couldn’t care less if they don’t launch another campaign at all. One Weibo user wrote: “Every day there’s a new collaboration here, another one there, but I’d just prefer a simple cup of tea.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Schoppa, Keith. 2000. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. New York: Columbia UP, 159.

[2]Zhong, Xueping. 2010. “Who Is Afraid Of Lu Xun? The Politics Of ‘Debates About Lu Xun’ (鲁迅论争lu Xun Lun Zheng) And The Question Of His Legacy In Post-Revolution China.” In Culture and Social Transformations in Reform Era China, 257–284, 262.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?