China Tech

More Details Emerge: Didi Killer Took 9000 RMB from Victim Before Murder

Published

6 years agoon

A day after the brutal killing of a female passenger using one of Didi’s car-hailing services made headlines in China, more details emerge about the circumstances of the homicide.

One of the most shocking details reported in Chinese media today is that the driver, the suspected murderer of the 20-year-old female, made her transfer an amount of 9000 yuan (±$1320) to his account before taking her life.

The driver reportedly had to drive to an area with better phone reception in order for the online transaction to succeed. Once the victim, a woman by the name of Xiao Zhao (小赵), had succeeded in transferring the money to his account via WeChat wallet, he raped her, stabbed her to death, and rolled her body off a cliff.

The incident took place during a so-called ‘Didi Shunfengche‘ (乘顺风车) ride, a car-pooling service from Chinese Uber-like company Didi Kuaidi, which was first introduced in 2015.

Chinese online news outlet The Paper reports that instead of choosing the highway – which would have taken around 40 minutes to her final destination -, the driver had taken a desolate mountainous route during the ride. At some point during this ride, he tied the hands and feet of Xiao Zhao so she couldn’t move, and taped off her mouth.

August 24:

±13:00: The 20-year-old Zhao from Wenzhou arranges a Didi ‘carpool’ ride from Hongqiao Town to Yongjia to attend a birthday party.

14:09: Xiao Zhao sends a WeChat message to a friend, saying. “I’m scared, the driver has taken a mountain road, there’s no one here.”

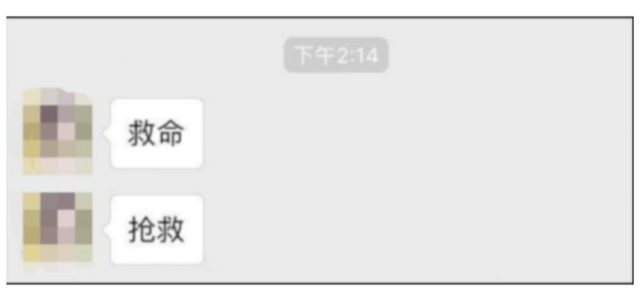

14:14: Xiao Zhao sends her last words to her friends via Wechat, writing “Help” (救命) and “Save me” (抢救).

“Help me,” Xiao Zhao cried for help through message before her phone lost contact.

15:42: After Xiao Zhao’s friend has contacted the Didi help desk seven times within the time frame of an hour, she is told to “please wait patiently.”

16:22: The friend informs Yongjia police of the situation.

17:35: The family members also report the case to the Yueqing police.

17:42: Xiao Zhao’s friend asks Didi customer service for the details of the driver, but is denied this information.

18:13: Didi provides police with the vehicle and driver information.

August 25:

4:00: The criminal suspect, the Didi driver, is arrested by local police, and admits to raping and killing the female passenger.

±6:00: Police and rescue workers find the victim’s body in a mountainous area near the road.

For the past two days, this case has been one of the main trending topics on Chinese social media, with many condemning the company for failing to protect (female) passengers against such dangers.

The inadequate response of customer service has been a major topic of discussion; they did not only fail to respond to this case in time, but earlier this week, another woman claimed she was harassed by the same driver, and customer service also did not take action against him.

It now appears that Didi has been outsourcing its customer service, resulting in service workers not having the authority nor ability to see into more detailed information about Didi’s registered drivers and ride information.

For now, Didi has taken down its entire ‘shunfengche‘ carpooling service nationwide. The service is different from its regular Didi service in that it allows car owners to drive people to their destination while they are going there themselves (much like hitchhiking), making some money by sharing the ride.

Meanwhile, many Chinese news media outlets report more background details on the suspect. The 27-year-old Sichuan native was a high-school dropout and a ‘left-behind child’ (留守儿童) – meaning his parents are migrant workers who had to leave their child in their more rural hometown while going out to work in the city.

This is the second murder of a female passenger using Didi’s services within four months time. For more informarion on this case, please check our report here.

By Manya Koetse, and Miranda Barnes

Follow @whatsonweibo

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Digital

China’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

It’s Gaokao time! For the first time, China’s Gaokao essay topic was about the latest AI developments, triggering discussions on social media.

Published

2 months agoon

June 7, 2024

This week, China’s National College Entrance Exams, better known as the “Gaokao” (高考), became one of the most-discussed topics on Chinese social media. ‘Gaokao,’ ‘AI,’ and ‘Gaokao essay’ were the hottest words on Weibo by the end of the week.

The Gaokao (literally: ‘higher exams’) are a prerequisite for entering China’s higher education institutions and are usually taken by students in their last year of senior high school. June 7th marked the first day of the Gaokao, which will continue until June 9th.

For the over 13.4 million participating students, the Gaokao week is a pivotal moment. Scoring high on this exam can grant access to better colleges, significantly improving their chances of obtaining a good job after graduation. Given the potentially life-changing results, the Gaokao period is a stressful time for both students and their parents.

The Gaokao essay (高考作文) is a significant component of the Chinese language exam, testing students’ writing skills, critical thinking, and ability to express ideas coherently. The essay, which must be completed within a limited time, requires students to discuss given topics.

These topics are generally related to Chinese society and culture, consistently attracting attention on social media. This year, multiple essay questions were related to AI and social media.

Those taking the Beijing exam (北京卷), for example, received a question related to the “like” function on WeChat, suggesting that some people feel strongly about the number of “likes” they receive and give, asking students to reflect on the phenomenon of receiving and giving “likes” on social media.

But the question receiving the most attention on social media was part of the New Curriculum Standard Test I (新课标I卷), which is distributed among different provinces.

Students vs. Chatbots: Letting AI Write an Essay on AI

Students received the following topic prompt for their Gaokao essay, which should be at least 800 characters long:

“With the spread of the internet and AI applications, we can quickly get answers to more and more questions. Will this also lead to us having fewer problems?” (随着互联网的普及、人工智能的应用,越来越多的问题能很快得到答案。那么,我们的问题是否会越来越少?)

The question sparked discussions because it was the first time a Gaokao essay question focused on AI applications designed to interact with users, like ChatGPT.

Although many thought the essay question was easy—unlike this year’s math exam—it still generated some interesting reflections.

Some Weibo users responded that the answer to the question was within the question itself. One Weibo blogger answered: “If there were no AI, we wouldn’t have this question, so problems/questions related to AI will only increase. The emergence of new things will inevitably be accompanied by new problems.”

Others commented on the concerns brought by the emergence of AI applications like ChatGPT. In early 2023, hashtags such as “Ten Professions That Could be Replaced by ChatGPT” (#可能被ChatGPT取代的10大职业#) gained a lot of attention on Chinese social media, where many were concerned that jobs from various industries, including customer service, programming, media, education, market research, finance, etc., would soon be done by AI chatbots instead of humans.

In line with this thought and the AI theme of this year’s Gaokao essay, netizens and some Chinese media outlets decided to let various language models take the exam and see how they would perform: could AI actually do better in writing an essay about AI than Chinese students? (Related hashtags: #让AI写高考作文#, #假如AI写高考语文作文#; #ChatGPT来交卷了#).

Xinhua, for example, asked Open AI’s ChatGPT to answer various questions. Sina Tech (新浪科技) also asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT to answer the AI-related essay question, along with Chinese chatbots, like Baidu’s Erniebot (文心一言), Tencent’s Yuanbao (元宝), iFlytek’s Sparkdesk (星火), and Alibaba’s Tongyi Qianwen (通义千问). Toutiao News did the same, letting three chatbots (ChatGPT, Erniebot, Tongyi Qianwen) compete against each other.

There is no general consensus on how well these AI chatbots can write a Gaokao essay. Although compared to last year, there are now more and better domestic AI models, OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 is generally still seen as the best chatbot out there.

This was its answer (originally in Chinese, translated to English with ChatGPT):

New Issues and Thoughts Brought by Technological Progress

With the popularization of the internet and the application of artificial intelligence, we can quickly obtain a large amount of information, and many questions can be answered in a short time. However, does this mean that we will have fewer questions? I believe the answer is no.

Firstly, although technology provides us with convenience, new technologies also bring new problems. The popularization of the internet has made information dissemination faster, but at the same time, the authenticity and accuracy of information have become new concerns. Fake news, information overload, and privacy breaches are increasingly prominent issues. These new problems need to be identified, understood, and resolved by us.

Secondly, the application of artificial intelligence, although it improves efficiency, also brings ethical and social issues. The transparency of AI decision-making, algorithmic bias, and the impact on the job market are all urgent issues that society needs to address. People need to constantly raise new questions to ensure a balance between technological progress and social welfare.

Furthermore, the development of technology prompts us to reflect more deeply on humanity itself. We need to rethink the relationship between humans and technology and consider the role and boundaries of technology in our lives. These philosophical issues are more important than ever.

Therefore, technological progress does not reduce our questions but rather prompts more new questions and reflections. It is these constantly emerging questions that drive social progress and human thought. We need to embrace the challenges brought by technology with a more open and critical attitude and actively seek solutions.

Although the domestic chatbots gave somewhat different answers, the overall tone was similar, though some commenters argued that ChatGPT was still the strongest, along with iFlytek’s Sparkdesk.

An online poll asking Weibo users to grade the ChatGPT essay from lower than 20 points up to the full 60 points saw divided responses, though a majority rated it as lower than 20 points.

How well can ChatGPT write an essay about AI? Opinions are divided.

This shows that many commenters think that AI chatbots are still not able to beat humans when it comes to writing Gaokao essays.

Commenters reacted to the various AI-generated essays in various ways, including:

• “Actually, none of them are very good. They are too formulaic and standardized, lacking the natural creativity and originality that humans possess.”

• “They just give soulless standard answers.”

• “It’s all about ‘firstly,’ ‘secondly,’ ‘furthermore.'”

• “There are no examples, no points proven; it should be a low grade.”

• “It’s just too stiff.”

• “This is like reading reports, not essays.”

• “AI places more emphasis on logic, which aligns with the writing style of foreigners.”

• “There’s no feeling in these essays; there’s a certain kind of AI feeling to AI.”

Meanwhile, some bloggers are taking up the challenge and are publishing their own online essays in response to the Gaokao question.

Some of them are not worried that chatbots will take over their critical tasks: “AI will be AI. There’s no connection to the social realities, and it’s as cold as ice.”

“Their words might make sense, but they lack feeling.”

But for some discussing the topic, they have come to realize that they are already depending too much on digital tools and AI applications for their everyday tasks, writing: “I made an attempt to write an essay, but discovered I already forgot how to do it!” For them, the discussion itself is a wake-up call that writing an essay from scratch is a skill that requires practice and cannot be fully replaced by chatbots, making personal creativity essential to score points and avoid the ‘AI-fication’ of texts.

PS:

In his book China’s Millennials, Eric Fish describes the limits on Chinese students’ answers; taboo responses, such as those containing harsh criticisms of the Chinese government or society, could potentially lead to failure. Although the essay is purportedly meant to showcase the student’s creativity, it must adhere to the unwritten rules of what is socially acceptable.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

Key takeaways about the ‘Xi Jinping chatbot’, jokingly referred to as ‘Chat Xi PT’ by foreign media outlets.

Published

2 months agoon

May 23, 2024

This week, various English-language newspapers reported that China is launching its very own Xi Jinping AI chatbot. China’s top internet regulator is reportedly planning to unveil a new chatbot trained on the political philosophy of Xi Jinping. This Large Language Model (LLM) is humorously referred to as ‘Chat Xi PT’ by the Financial Times and in other foreign media reports.

The Times of India website headlined that “China builds AI chatbot trained on Xi Jinping’s thoughts.” News site Asia Financial reported that “China has unveiled a chatbot trained to think like President Xi Jinping.” Various outlets even called it a “ChatGPT chatbot based on Xi Jinping.”

The Financial Times calls the application “China’s latest answer to OpenAI” and notes that “Beijing’s latest attempt to control how artificial intelligence informs Chinese internet users has been rolled out as a chatbot trained on the thoughts of President Xi Jinping.”

Besides the Financial Times article by Ryan McMorrow, media reports were largely based on a piece in the South China Morning Post authored by Sylvie Zhuang, titled “China rolls out large language model AI based on Xi Jinping Thought.”

Zhuang detailed how Xi Jinping’s political philosophy, along with other themes aligned with the official government narrative, form the core content of the chatbot, which is launched at a time when China “tries to use artificial intelligence to drive economic growth while maintaining strict regulatory control over cybersecurity.”

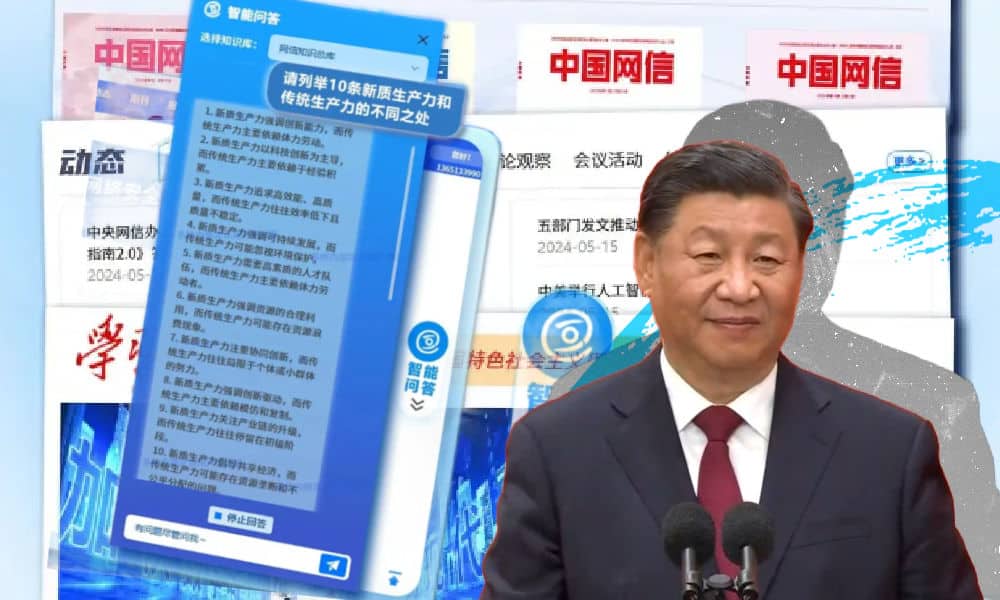

News about the supposed “Xi Jinping chatbot” is based on a post published on the WeChat account of the Cyberspace Administration magazine.

The magazine in question is China Cyberspace (中国网信), overseen by the Cyberspace Administration of China (国家互联网信息办公室) and published by the China Cyberspace Research Institute (中国网络空间研究院).

“Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application”

On May 20, China Cyberspace (中国网信杂志) posted the following text on WeChat, which was viewed less than 6000 times within two days (translation by What’s on Weibo):

“Recently, the Cyberspace Information Research Large [Language] Model Application developed by the China Cyberspace Research Institute has been officially launched and is being tried out internally.” [1]

“As an authoritative and high-end think tank in the Cybersecurity and Informatization field, the China Cyberspace Research Institute relied on the data of the “Internet Information Research Database” and organized a special tech team to independently develop the Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application, to take the lead in demonstrating the innovative development and application of generative AI technology in the field of Cybersecurity and Informatization.”

“The corpus of this Large Model [LLM] is sourced from seven major speciality knowledge bases within the “Internet Information Research Database,” including the “Comprehensive Database of Cyber Information Knowledge”, the “Knowledge Base of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” “Dynamic Cyber Knowledge Base,” “Internet Information Journal Knowledge Base,” “Internet Information Report Knowledge Base,” and more. Users can independently select different categories of knowledge bases for smart question-and-answering. The specialization and authority of the corpus ensures the professionalism of the content that’s generated.”

“Do you want to quickly make a summarized report on the current status of AI development? Are you curious about the differences between ‘new quality productive forces’ and ‘traditional productivity’? This Large Model application can quickly produce it for you!”

“The Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application is based on domestically registered open-source and commercially available pre-trained language models. By combining Information Retrieval technology with specialized Cyberspace Information knowledge, it can do smart question-and-answering [Q&A chatbot], it can generate articles, give summaries, do Chinese-English translations, and many other kinds of tasks in the field of Cybersecurity and Informatization to meet the various demands of users.”

“The system used for the Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application is deployed on a dedicated local server of the China Cyberspace Research Institute. Data is processed from this local server, ensuring high security. This application will become one of the embedded functions of the “Internet Information Research Database” and authorized users invited for targeted testing can access and use it.”

“The Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application will also support users to customize and build new knowledge bases. Users uploading public data and personal documents can analyze and infer, further expanding the scope of personalised use by users.”

Although some Chinese media sources reported on the launch of the application, it barely received traction on Chinese social media.

At the time of writing, the only official accounts posting about the application on Chinese social media are those related to research institutions or the Cyberspace Administration of China.

Key Takeaways on the “Chat Xi PT” Application:

So what are the key takeaways about the so-called, supposed ‘Chat Xi PT’ application that various foreign media have been writing about?

■ Focus on Cyberspace Administration and Digital Governance:

Contrary to some English-language media reports, the application is not primarily centered around Xi Jinping Thought but rather emphasizes Cyberspace Administration and digital governance. Its official name, the “Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application” (网信研究大模型应用), does not even mention Xi Jinping.

■ Not a Rival to OpenAI’s ChatGPT:

Unlike what has been suggested in the media reports, this particular application should not be seen in the light of China “creating rivals to the likes of Open AI’s ChatGPT” (FT). Instead, it caters to a specific group of users engaged in specialized research or operating within certain knowledge fields. There are many others (commercial) chatbots in China that could be seen as Chinese alternatives to OpenAI’s ChatGPT. This is not one of them.

■ Modernization of Cyberspace Authorities:

Rather than solely meeting user demand, the application underscores China’s Cyberspace authorities’ modernization efforts by integrating generative AI technology into their own platforms.

■ Clarifying “Xi Jinping Thought”:

Various English-language media reports conflate “Xi Jinping Thought” with “thoughts of Xi Jinping.” “Xi Jinping Thought” specifically refers to “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” the theories, body of ideas that were incorporated into the Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party in 2017.

■ Nothing “New” about the Application:

The ‘Cyberspace Information Research Large Model Application’ is based on existing LLMs and functions as a tool for navigating databases and information in the AI era, rather than representing a groundbreaking innovation or an actual ‘Xi Jinping chatbot.’ While it may have been written as a tongue-in-cheek headline, let’s be clear: there is no such thing as a ‘Chat Xi PT.’

By Manya Koetse

[1]About the translation of the term “网信” (wǎngxìn): in this text, I’ve used different translations for the term “网信” (wǎngxìn) depending on the context of its use. The term can be translated into English as “cyberspace” or “internet information,” but since it is mostly used in relation to China’s Cyberspace Administration and digital governance, it is sometimes more appropriate to refer to it as Cyberspace Security and Information,like the term “国家网信部门” which translates to “national cybersecurity and informatization department” (Also see translations by DigiChina).

🌟 Attention!

For 11 years, What’s on Weibo has remained a 100% independent blog, fueled by my passion to write about China’s digital culture and online trends. Over a year ago, we introduced a soft paywall to ensure the sustainability of this platform. I’m grateful to all our loyal readers who’ve subscribed since 2022. Your support has been invaluable. But we need more subscribers to continue our work. If you appreciate our content and want to support independent China reporting, please consider becoming a subscriber. Your support keeps What’s on Weibo going strong!

Full Text by China Cyberspace:

“近日,由中国网络空间研究院开发的网信研究大模型应用已正式上线并内部试用。

垂直专业:聚焦网信领域

作为网信领域权威高端智库,中国网络空间研究院依托“网信研究数据库”数据,组织专门技术团队,自主开发了网信研究大模型应用,率先示范生成式人工智能技术在网信研究领域的创新发展和落地应用。

该大模型语料库来源于“网信研究数据库”的七大网信专业知识库,包括“网信知识总库”“习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想知识库”“网信动态知识库”“网信期刊知识库”“网信报告知识库”等。用户可自主选择不同类别的知识库进行智能问答。语料库的专业性、权威性保证了生成内容的专业性。

便捷高效:实现多种功能

想快速列出关于人工智能发展现状的报告提纲?想知道新质生产力和传统生产力的不同之处?网信研究大模型应用能够迅速生成!

网信研究大模型应用基于已备案的国内开源可商用预训练语言模型,通过将检索增强生成技术和网信专业知识相结合,实现了网信领域的智能问答、文稿生成、概括总结、中英互译等多种功能,可满足用户的多种需求。

安全可靠:数据本地处理

网信研究大模型应用系统部署在中国网络空间研究院的专属本地服务器,数据由本地服务器进行处理,具有较高的安全性。该大模型应用将成为“网信研究数据库”的嵌入功能之一,获得授权的定点测试用户可以应邀使用该应用。

网信研究大模型应用还将支持用户自定义新建知识库,可通过加载用户自己上传的公开数据、个人文档进行分析推理,进一步拓展用户的个性化使用范围。”

Featured image by What’s on Weibo, image of Xi Jinping under Wikimedia Commons.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Alex

August 27, 2018 at 12:58 pm

Great summary as usual. Would it be possible for you to also include the pinyin when writing the Chinese characters? It’d make it much easier to learn the pronunciation any characters I don’t recognize. Some articles have it already (快狗 article for instance).