Featured

Keeping Peace, Building Power: China & International Peacekeeping (Liveblog)

Recently, the Chinese government has made historical moves involving China’s role in international peacekeeping. Today’s seminar focuses on the China’s role within the international peacekeeping community.

Published

10 years agoon

Seminar: China’s Role in International Peacekeeping

Date & Place: Nov. 25, 2014, The Hague Institute for Global Justice

Organized by: Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Blogged by: Manya Koetse

Recently, the Chinese government has made historical moves involving China’s role in international peacekeeping. In early 2014, the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) send a motorized infantry brigade to Mali. In September this year, a 700-strong infantry troop was send to South-Sudan as part of a UN peacekeeping mission – the first Chinese battalion to participate in such a peacekeeping operation (GT 2014; ECNS 2014). The recent behavior of Chinese leaders in issues of international conflict contrasts with Chinese participation in peacekeeping operations in the 1970s and 1980s. Today’s seminar focuses on China’s role within the international peacekeeping society.

Introduction (14:00 GMT+1)

Peter Potman, Director Asian and Pacific Affairs Department (Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs) is the first speaker on today’s seminar.

China as an actor in the international political arena is gradually gaining significance, Potman says, as its role in global politics is transforming: China is becoming more assertive. China’s position within international conflict situations is profoundly changing. Its role used to be one of non-interference, but is now changing as the political leadership is getting more involved in issues playing in Sudan or Syria.

Today’s seminar has two keynote speakers: Frans-Paul van der Putten from the Clingendael Institute and Dr. Jing Gu from the Institute of Development Studies. But first Christina Jansen shortly addresses the role of China today in international peacekeeping. Jansen recalls how she first arrived in China in 1978, and remembers how she would involuntarily cause a traffic jam because so many people would stare at this foreigner standing next to the road. “How China has changed!” Jansen says. The central question of today is: does the quick transformation of China as a nation also have implications for the international order in security issues, and if, how?

China and International Security (14:20 GMT+1)

Balance is crucial for China as an actor within international security issues, Van der Putten says. He states that China has to find its balance in different areas. First, it has to deal with the growing number of Chinese people and companies outside of China, and has to think about how to protect them without becoming over-involved and making the same ‘mistakes’ as western nations have made in the past. Secondly, it has to find its role in the international system where the national identity of China has to be communicated on an international level in such a way that it preserves the Chinese identity. Lastly, China also has to balance between its role as being one of the global powers and being one of the leaders within the developing world.

How does this translate to security issues? China already is a permanent member of the Security Council but is still looking for ways to strengthen its position. China finding its balance is noticeable in how it acts, Van der Putten states, not only as a member of the International Security Council but also as a leader in regional security organizations, where China increasingly is taking in an assertive position as a regional power.

“There’s a big difference between China’s principles and how it acts in reality.”

China and International Security (14:40 GMT+1)

China’s role within international peacekeeping cannot be compared to that of other nations, according to Jing Gu. China’s international peacekeeping framework should be seen within China’s development at large. What one can now discern, says Gu, is the difference between China’s principles and how it acts in reality. According to principles, the Chinese government strictly respects the sovereignty of other countries and has a non-intervention principle. But in reality, their principles turn out to be much more flexible than they are on paper.

Dr. Gu is convinced that one can never leave out the economic perspective when talking about China’s engagement in peacekeeping operations. Business plays a big role in China’s international development cooperation; the business sector is increasingly important for China in, for example, Africa. Western nations have to take this perspective in account when cooperating with China in international security matters.

“For China, ‘peacekeeping’ truly is about peace keeping, not about peace building.”

There are differences in what Western nations and China consider ‘international peacekeeping’. From the Chinese perspective, it is very much about actual ‘peace keeping’ and not ‘peace building’, Gu says: a major difference with what most western powers consider to be ‘peacekeeping’. Using force is not something Chinese leaders want to do, as non-interference is a high principle for the government. But, Gu stresses again, “principles are just principles; in reality these principles are very flexible, as we’ve seen in Africa.”

What can be done on the long term to involve China in international security collaborations? “It has to be taken case by case,” Gu says. It is not the right time for general talks about future collaborations and shared frameworks- step by step and case by case, China will become more involved in international peacekeeping, Gu predicts, as is happening in Sudan right now.

Discussion (15:20 GMT+1)

“Over the past 500 years there have been many power shifts that have not led to war,” panelist Tim Sweijs of The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies says. However, every transformation in global power systems do have major consequences. States in the international system start harboring different expectations as power relations shift. This is what is also happening as China starts behaving differently within the international arena and takes on a different role in security issues. Different political actors seem worried that China is concerned about protecting its own national interests. These “worries” are “suspicious,” Sweijs says, because: “are western powers not concerned about own national interests?”

In the conclusion of the seminar, Peter Potman stresses that nations in peace operations need to be fully aware of their differences before they can work on collaboration. There are often mutual and shared benefits to participate in a peacekeeping mission. While those shared interests are often clear, it is crucial to also elucidate the different interests in these operations. Who is participating for what reasons? Understanding these underlying motives helps in unraveling the web of international cooperation in global security issues – finally building on peacekeeping missions where all participating nations, including China, are looking in the same direction.

(This liveblog is now closed.)

References

ECNS. 2014. “Peacekeeping forum opens in Beijing.” ECNS, 15 Oct. http://www.ecns.cn/2014/10-15/138449.shtml (Accessed November 25, 2014).

Global Times (GT). 2014. “Peacekeeping can help China stand tall.” Global Times, 19 Nov. http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/892646.shtml (Accessed November 25, 2014).

Images

http://www.uscnpm.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/un.jpeg

Liu Rui/Global Times

Manya is the founder and editor-in-chief of What's on Weibo, offering independent analysis of social trends, online media, and digital culture in China for over a decade. Subscribe to gain access to content, including the Weibo Watch newsletter, which provides deeper insights into the China trends that matter. More about Manya at manyakoetse.com or follow on X.

China Memes & Viral

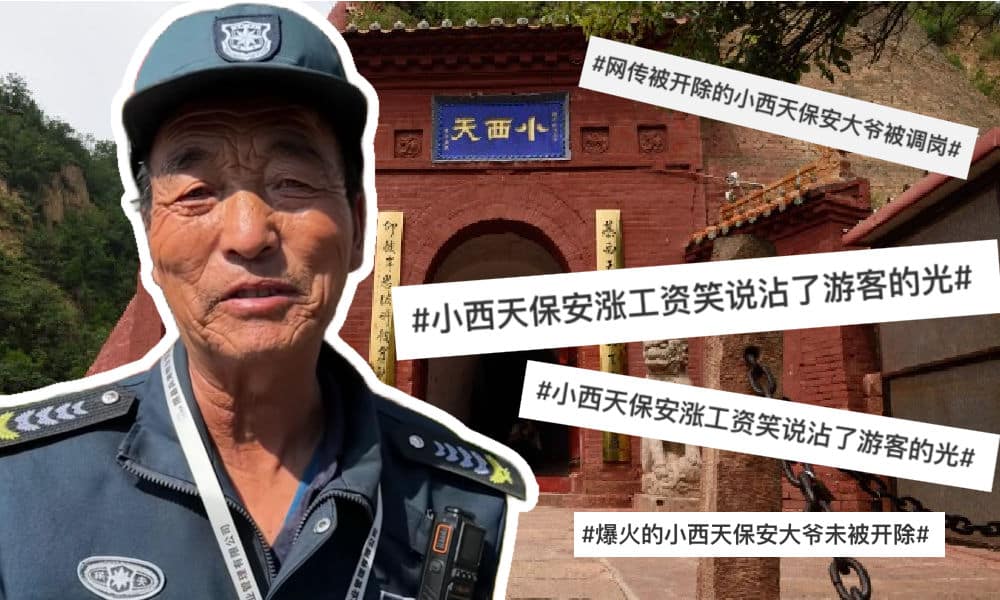

The Viral Bao’an: How a Xiaoxitian Security Guard Became Famous Over a Pay Raise

Most netizens aren’t buying the story about the Xiaoxitian bao’an allegedly “misunderstanding” his dismissal.

Published

1 day agoon

October 23, 2024

An elderly man with a friendly face from Shanxi Province’s Xi County became China’s most famous security guard this week. After first receiving a raise and then seemingly being fired from his job, the situation sparked so much discussion that it became a top trending topic on Weibo.

The man in question is a bǎo’ān (保安, security guard) at the Xiaoxitian (小西天) temple complex area in Xi County in the city of Linfen. That area has recently became a hot destination among domestic travelers because of the wildly popular video game Black Myth: Wukong. The game, inspired by the classic novel Journey to the West, features numerous real-life landmarks from Shanxi province.

As a so-called “Wukong site,” Xiaoxitian, among with dozens of other spots in Shanxi, has seen a surge in visitors, including gaming bloggers, travel vloggers, and online influencers.

One of these influencers is the Douyin vlogger “So Many Times” (@那么多曾经), who has been documenting the success of Xiaoxitian on her channel. The vlogger, who now has 12,000 fans, has been capturing the rising number of visitors to the area, especially during this year’s National Day holiday.

Her videos often focus on the best times to visit without having to queue, traffic updates, and daily visitor counts. In one video, she even captured the first group of foreign tourists visiting the area.

“They gave me a raise”

Recently, the vlogger also featured some of the security guards at Xiaoxitian, chatting with them about their local dialect, their work, and how they manage the crowds.

In the videos by “So Many Times,” the vlogger focused on one particular security guard—an elderly bao’an who was especially friendly to her. In several videos, he shared how much he enjoyed his job and the increasing responsibilities that came with Xiaoxitian’s growing popularity. He soon became affectionately known among visitors as the “Security Guard Uncle” (保安大叔).

The security guard became popular online due to videos posted by a Douyin vlogger.

In a video posted on October 15, the bao’an happily shared how grateful he was for the visitors. Smiling, he said, “I attended a meeting, and they gave me a raise. I used to earn 1,700 yuan (US$240) a month, and they added 500 yuan (US$70), so now it’s 2,100 (he meant 2,200 yuan/US$310). Everyone’s salary went up.”

The security guard suggested the tourists were to be thanked for local bao’an getting a better pay, as it increased their workload.

Uncle Bao’an tells about his 500 yuan raise.

The video quickly went viral—becoming the most-watched on the vlogger’s channel—as some viewers appreciated how ‘influencer tourism’ can benefit local workers. Others, however, were surprised by the 1,700 yuan/month (US$240) salary, considering it far too low. Beyond these discussions, the uncle’s friendly demeanor, humble enthusiasm, and obvious passion for his work touched many hearts.

A news reporter for Jimu News verified with the local citizen hotline that the minimum monthly wage in Xi County is 1,780 yuan ($250), and that the 1,700 yuan salary previously mentioned by the security guard was below this standard.

A few days later, on October 19, the Douyin vlogger whose videos made ‘Uncle Bao’an’ famous posted another short video (which has since been taken down). In this video, the security guard looked tired and said, “They [the superiors] told me not to work anymore. I didn’t say anything wrong, but they don’t want me to continue.”

He explained that his leaders thought it was inappropriate for him to appear in the other videos, though he felt it was spreading positive energy.

“These past few days, I haven’t been feeling well. They don’t want me to work, and I’m very sad.. I will never forget everyone’s support.”

“He didn’t hear it clearly”

News of the popular security guard’s alleged dismissal flooded the internet, becoming one of the hottest topics on Weibo.

Many netizens were outraged, feeling that the bao’an was unfairly forced to stop doing his job. They suggested he was dismissed because he disclosed information about his pay and the recent raise.

In light of the online controversy, the local tourism authorities responded to clarify the situation on October 20.

A spokesperson from Linfen suggested that the bao’an had not heard it clearly (“他就没听清楚”), and was not dismissed at all. Instead, he was simply given a few days off and “reassigned to a less demanding role” to lighten his workload, considering his age and the fact that he had been working without a break for the past two months.

“We all heard it clearly”

On social media, most netizens aren’t buying the story about the bao’an allegedly “misunderstanding” his dismissal.

“Do they think we’re fools? Do they think we haven’t all seen the video on the 19th?” one commenter wrote.

“Ha ha ha, if this hadn’t blown up online, he would have been fired. But because it went viral, now he’s ‘transferred to another post,’” another Weibo user remarked.

“We all heard it clearly,” another blogger added.

“Okay” / “Sure” – a meme posted by netizens after hearing about the security guard allegedly “misunderstanding” his dismissal.

People suspected that the security guard was initially fired—possibly for speaking about his low income or because he was becoming a tourist attraction himself—but the decision was reversed after it sparked public outrage online. Rather than offering an apology, the authorities then claimed it was all just a misunderstanding.

In light of the controversy and worried over the bao’an’s well-being, other Douyin users visiting Xiaoxitian began searching for the popular security guard and filmed themselves finding him at a different location. In one such video, ‘Uncle Bao’an’ confirmed that his superiors had reassigned him to lighten his workload. Some viewers commented that he didn’t seem as happy as before.

However, in the latest video by “So Many Times” (@那么多曾经), the vlogger once again features her favorite bao’an. (She used a new account for this, as her original account was restricted from posting new videos). In the video, he expresses his gratitude and happiness for the overwhelming support he has received.

“I want to thank all of you online friends for your support and your concern for me. It makes me very happy. Thank you. so many people wanted to take a picture with me today. People from Henan, from Sichuan. So many people wanted to shake my hand.”

Despite the controversy, the bao’an seems quite pleased with his sudden fame. If he does end up losing his job after all, he could always launch a new career as an online influencer.

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Society

Death of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

After the tragic death of young motorcyclist ‘Shigao ProMax,’ netizens criticize influencers for reckless riding in pursuit of followers and likes.

Published

3 weeks agoon

October 2, 2024

A Chinese female motorcyclist from Suzhou, known as “Shigao ProMax” (@石膏ProMax) on Douyin, tragically passed away this week following a motorcycle crash in Suzhou’s Wujiang District.

The incident occurred in the late afternoon of September 29, when the 19-year-old Shigao, whose real name was Yang Huizi (杨惠子), was a passenger on the motorcycle, with her (male) friend driving the vehicle.

As the motorcycle collided with a car emerging from a side intersection, Yang was thrown off the back, propelled several meters through the air before landing on the road. Although she was reportedly wearing a helmet, it cracked during the crash, and she sustained a severe head injury.

A video circulating on social media shows the aftermath of the accident, with the motorcycle driver lying on the road and Yang Huizi a few meters away, initially attempting to crawl before collapsing (warning for graphic content). Despite rescue efforts, she later died in the hospital. The current condition of Yang’s friend, the rider, remains unclear.

Screenshot of the scene of the accident.

Yang had nearly 80,000 fans on Douyin, where she posted her first video in December 2019. By September 2024, she had shared a total of 1,298 videos.

On Weibo, many commenters voiced concern over how the news was headlined, criticizing the emphasis on her gender in the hashtag. The hashtag “Famous Female Rider Shi Gao Dies in Traffic Accident” (#网红女骑士石膏发生车祸身亡#) garnered over 170 million views on Weibo on Tuesday. Many commenters felt the headline made it seem as if the young woman had crashed the motor herself, while she was merely a passenger.

Others, however, see this trending news as an opportunity to highlight the risky behavior of motorcyclists, who not only endanger their own lives by speeding but also jeopardize the safety of others by showing off in traffic and driving recklessly.

Especially female influencers/motorcyclists are criticized for careless driving while flaunting their looks for social media posts.

Over the past years, the death of multiple motorcycle influencers have made Chinese headlines. In 2022, a popular Douyin influencer and motorcyclist known as “Xiaoyu Loves Eating Fish” (@小鱼爱吃鱼) died in a collision after riding in the wrong lane. She was instantly killed on the spot. Xiaoyu had gained attention for her risky driving behavior, often wearing short skirts, tight leggings, or other revealing outfits instead of proper motorcycle gear.

“Xiaoyu Loves Eating Fish,” images via Tencent News

In 2023, two young girls—one 16 and the other 21—tragically lost their lives after their motorcycle crashed into a pillar. They were speeding and, apart from wearing helmets, were dressed in skirts and stockings with no additional protective gear. Both died instantly. The 16-year-old, known as An’an (安安), was a social media influencer. Her followers had previously warned her about her reckless behavior. She rode a motorcycle without a license.

An’an’s social media profile.

Within one year alone, from October 2022 to September 2023, at least seven motorcycle influencers made headlines in China after losing their lives in traffic accidents. Some bloggers blame the intense competition for online attention for these accidents, as influencers pull dangerous stunts and push the boundaries to gain more likes and followers.

Posting a video of a woman posing for a video while riding a motorcycle, the popular Weibo content creator HuangXiPao (@黄西炮) wrote: “So many female motorcycle influencers have died, yet it doesn’t stop others from still posing on the road for photos! Is this trend really that profitable?”

One commenter expresses frustration over how news about motorcycle influencers consistently reaches the top trending lists, while other serious incidents, such as the big stabbing incident that happened in Shanghai this week, seem to be kept off the hot lists. “Every time a female motorcycle influencer dies, it makes the trending lists. Meanwhile, three people are dead and 18 injured in Shanghai! Yet you’ve completely suppressed the search term (…) What is this about?!”

News about the motorcycle incident is also a reason for official channels to remind netizens about road safety. The official China Police account shared photos of the incident, stating: “Raise safety awareness and take responsibility for your life.”

By Manya Koetse

(follow on X, LinkedIn, or Instagram)

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

The Viral Bao’an: How a Xiaoxitian Security Guard Became Famous Over a Pay Raise

The Hashtagification of Chinese Propaganda

Hidden Hotel Cameras in Shijiazhuang: Controversy and Growing Distrust

Death of Chinese Female Motorcycle Influencer ‘Shigao ProMax’ Sparks Debate on Risky Rides for Online Attention

Why the “人人人人景点人人人人” Hashtag is Trending Again on Chinese Social Media

About Wang Chuqin’s Broken Paddle at Paris 2024

“Land Rover Woman” Sparks Outrage: Qingdao Road Rage Incident Goes Viral in China

Weibo Watch: The Land Rover Woman Controversy Explained

China at Paris 2024 Olympics Trend File: Medals and Moments on Chinese Social Media

Stolen Bodies, Censored Headlines: Shanxi Aorui’s Human Bone Scandal

Fired After Pregnancy Announcement: Court Case Involving Pregnant Employee Sparks Online Debate

Weibo Watch: Going the Wrong Way

Team China’s 10 Most Meme-Worthy Moments at the 2024 Paris Olympics

Weibo Watch: Shaping Olympic Narratives

“No Kimonos Allowed” – Ongoing Debate on Japanese Attire in China

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight6 months ago

China Insight6 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music7 months ago

China Music7 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Insight8 months ago

China Insight8 months agoThe ‘Two Sessions’ Suggestions: Six Proposals Raising Online Discussions

-

China Insight11 months ago

China Insight11 months agoThe Story of Li Jun & Liang Liang: How the Challenges of an Ordinary Chinese Couple Captivated China’s Internet