China Arts & Entertainment

Top 30 Classic TV Dramas in China: The Best Chinese Series of All Time

This year marks 60 years of Chinese TV drama. These are the best Chinese TV dramas of all time.

Published

6 years agoon

PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

First published

They might have aired 30 years ago, but some TV dramas just never get old. We have listed the greatest classic Chinese TV dramas of all time, that, either because of their high-production value or historic ratings, are still talked about today. A special overview by What’s on Weibo, as China celebrates 60 years of TV drama this year.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Chinese TV drama since the airing of the very first (one-episode) drama A Mouthful of Vegetable Pancakes (一口菜饼子) in 1958 – the same year in which the very first Chinese television station started broadcasting (Bai 2007, 77).

The drama, live broadcasted by Beijing Television, sent out a message of frugality, as one young girl warns her sister not to waste food by remembering her of their difficult past and brave mother, who died of hunger while even refusing to eat the last bit of food, a vegetable pancake.

A Mouthful of Pancakes aired in 1958.

Much has changed within those sixty years. After a time when the production of TV dramas practically came to a standstill during the Cultural Revolution, the late 1970s and early 1980s saw a boom in the popularity of television dramas, along with a spike in households that owned their own TV. From 1980 to 1990, the number of household television sets in China increased from 5 to 160 million (Wang & Singhal 1992, 177).

Since the 1980s, mainland China has gone from a country where most television dramas were imported from outside the country, to one that has the most thriving domestic TV drama industry in the world.

Some TV dramas in this list have become classics through time, some are fairly new but have already become classics within their genre.

This list has been fully compiled by What’s on Weibo, based on popularity charts on Chinese search engine Sogou’s top tv drama listings of all time, together with ranking on Douban, a big Chinese social networking service and influential media review website, and also based on academic sources that note the importance of some of these TV classics.*1 We will list a recommendation list of relevant books at the end of this article.

Most of these series will have links redirecting to available versions on Youtube or elsewhere – unless written otherwise, they do not have English subtitles. Please share English subtitled versions in the comment section if you found them, we’ll add them to the list.

This article is focused on those classics that have been important for the TV drama industry and audiences of mainland China. Although several of them were produced in Hong Kong or Taiwan, the majority is from the PRC. These dramas are listed in chronological order of appearance, not listed based on rankings.

Here we go!

#1 The Bund / The Shanghai Bund (上海滩)

Year: 1980

Episodes: 25

Genre: Action

Produced in Hong Kong

Noteworthy: “The Godfather of the East”

This TV drama became such a sensation across China in 1980, that it also became known as the Chinese equivalent to the classic Godfather series.

Actors Angie Chiu and Chow Yun-Fat star in this Hong Kong drama, that is set in the underworld society of 1920s Shanghai, and revolves around the tumultuous love story between Feng Chengcheng and Xu Wenqiang.

The series has become such a classic that it still plays an important role in popular culture of China today, with newer films and TV dramas also being based on the original series (the 2007 mainland China TV series Shanghai Bund, for example, is a remake of the 1980 original). If you ever go to karaoke, you’re probably already familiar with the shows’ famous theme song ‘Seung Hoi Tan’ (上海滩) by Frances Yip (see here).

#2 Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp (敌营十八年)

Year: 1981

Episodes: 9

Genre: War Drama

Watch the first episode here on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “The first TV drama produced by CCTV”

Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp is somewhat of a cult classic in China. Despite the fact that the TV drama itself was somewhat poorly produced, it still gets high ratings on sites such as QQ Video or Douban today.

At a time when the Chinese TV drama market was still dominated by imported television series (from Hong Kong, US, and other places), Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp was the first drama series made by CCTV (Bai 2007, 80), directed by Wang Fulin (王扶林) and Du Yu (都郁).

The story revolves around the Communist Party member Jiang Bo (江波), who spends 18 years undercover in the “tiger’s den” (虎穴), the enemy’s camp, as a National Army officer, thwarting the Nationalists’ plans until the 1949 victory of the Communists.

Fun fact by Ruoyun Bai (see references): despite the fact that the entire show is about the Nationalists Army, not a single Nationalist Army uniform could be found for the cast. The uniforms that were used, were not up to par: the main character had to leave his coat’s collar unbuttoned because it was too tight, and always has his hat in his hands because it was actually too small to fit his head (2007, 80-81).

#3 Ji Gong (济公)

Year: 1985

Episodes: 12

Genre: Fantasy

Directed by Zhang Ge (张戈)

All episodes can be watched here on YouTube.

Noteworthy: “Influenced by Charlie Chaplin”

This popular TV series is centered around Ji Gong, the folk hero and Chan Buddhist monk who lived in the Southern Song and, according to legend, had supernatural powers and spent his whole life helping the poor.

The main role is played by renowned Chinese artist and mime master You Benchang (游本昌). In an interview with CRI, the actor once said that he was heavily influenced by his idol Charlie Chaplin for this role, sometimes even imitating some of Chaplin’s gestures.

#4 Chronicles of The Shadow Swordsman (萍踪侠影)

Year: 1985

Episodes: 25

Genre: Wuxia/Martial

Directed by: Wang Xinwei (王心慰)

Produced in Hong Kong

Episodes available on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Perfect Chemistry between Leading Actors”

This classic TV drama features actors Damian Lau as Zhang Danfeng and Michelle Yim as Yun Lei, whom are often praised by drama lovers for their perfect chemistry in these series. Of the many adaptations there are of Liang Yusheng’s wuxia novel Chronicles of The Shadow Swordsman, many say this is their favorite.

#5 New Star (新星)

Year: 1986

Episodes: 12

Directed by: Li Xin (李新)

Noteworthy: “A drama anyone over 50 will remember”

This CCTV mini-drama, based on the novel by Ke Yunlu (柯云路), tells the story of a young Party secretary fighting against corruption. Before Heaven Above (later in this list), it is thus one of the very first dramas to focus on corruption as a theme, and it also caused a buzz at the time for doing so – most people over 50 in China today will probably remember this TV series today.

#6 Journey to the West (西游记)

Year: 1986

Episodes: 25 for season one, 16 episodes for season 2

Directed by Yang Jie (杨洁)

Watch on Youtube (with English subtitles!) here.

Noteworthy: “Shot with one camera”

This is an all-time favorite TV series in China that is still rated with a 9.5 on the TV drama database of search engine Sogou. It has been an instant classic from the moment it was first broadcasted by CCTV in October of 1986.

Journey to the West (Xīyóu jì 西游记), published in the 16th century (Ming dynasty), is one of the most important classical works in the history of Chinese literature, and tells the story of the long journey to India of the Tang Monk Xuánzàng, who is on a mission to obtain Buddhist sutras. He is joined by three disciples, the pig demon Zhū Bājiè, the river demon Shā Wùjìng, and Sūn Wùkōng, who is better known as the Monkey King in the West.

The Monkey in the series is played by Zhang Jinlai (章金莱), also known as Liu Xiao Ling Tong, who recently recalled in an CGTN article that: “it was 30 years ago and we’d got only one camera. We walked around China’s picturesque areas and took 17 years to make 41 episodes. 17 years equals Monk Xuanzang’s pilgrimage for the Buddhist scriptures.”

#7 “The Dream of Red Chambers” (红楼梦)

Year: 1987

Episodes: 36

Directed by: Wang Fulin (王扶林)

Watch with English subtitles on YouTube here.

Noteworthy: “The first entry of Chinese tv drama into the global market”

Even today, this CCTV TV series from 1987 is still rated as one of the best Chinese television series of all time on Sogou, where viewers rate it with a 9.6.

Like other series in this list, this is an adaptation from a classic literary work; Dream of the Red Chamber (Hónglóumèng), one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels, which was written by Cao Xueqin in the mid-18th century during the Qing.

In June of 1987, this TV drama became the first Chinese television series to be exported to Malaysia and West-Germany, making it “the first entry of Chinese tv drama into the global market” (Hong, 32).

#8 The Investiture of the Gods (封神榜)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 36

Genre: Fantasy/Costume Drama

Directed by: Guo Xinling (郭信玲)

The first episode is available on YouTube here.

Noteworthy: “Based on the classical novel Fengshen Yanyi“

This TV series is based on the classical novel Fēngshén Yǎnyì (封神演義), also known as Investiture of the Gods or Creation of the Gods), written by Xu Zhonglin and Lu Xixing. Famous Chinese actor and painter Lan Tianye (蓝天野) was praised for his role as Jiang Ziya in this drama.

The (female) director Guo Xinling (1936-2012) was a Party member who worked on many televised works during her career.

Just as many others of the series in this list based on classic novels, there are remakes of these series in recent times.

#9 Yearnings / Kewang (渴望)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 50

Genre: Family drama

Directed by Lu Xiaowei (鲁晓威) and Zhao Baoguang (赵宝刚).

Noteworthy: “China’s first soap opera – a national craze”

Yearnings is also known as China’s real first soap opera, which caused a sensation across the nation – sales of TV sets surged, and streets were empty when it aired.

The story’s time spans from the Cultural Revolution until the 1980s reform period. The series, set in Beijing, tells the story of working-class woman Liu Huifang and her unlikely marriage to the middle-class Wang Husheng, a university graduate who comes from a family of intellectuals. When Huifang finds an abandoned baby, she adopts it against the will of her husband.

As the first TV series that focused on the hopes and dreams of ordinary Chinese people, the success of Yearnings was unprecedented, and it formed the beginning of Chinese television drama as we know it today.

#10 River of Gratitude (江湖恩仇录)

Year: 1989

Episodes: 20

Genre: Wuxia/Martial

Directed by: Mao Yuqin (毛玉勤)

Watch first episode on Youtube here

Noteworthy: “A true classic – it’s nostalgia!”

One of the main stars in this series is actress and producer Wenying Dongfang (东方闻樱), who also starred in A Dream in Red Mansion (1987).

By commenters on Douban, this series is described as a “cult classic.” Although some say the quality of the series, now, looking back, is somewhat substandard or silly, according to many, the nostalgia of seeing it in the early 1990s and being excited about it seems to play a major factor in why people still grade this one as a true classic – it’s nostalgia!

#11 Wan Chun (婉君)

Year: 1990

Episodes: 18

Produced in Taiwan

Noteworthy: “The first Taiwanese TV series filmed in mainland China”

Wan Chun is a 1990 Taiwanese television series about a girl named Wan Chun and her three adoptive brothers, that is based on the 1964 novel “Wan-chun’s Three Loves” (追尋) by Taiwanese writer and producer Chiung Yao, and which is set in Republican era Beijing.

This is the first cross-strait co-production, as a Taiwanese TV series filmed in mainland China. Wan Chun was followed up by the 1990 Taiwanese television drama series Mute Wife based on Chiung Yao’s 1965 novelette of the same name.

#12 The Legend of Qianlong (戏说乾隆)

Year: 1991

Episodes: 41

Genre: Imperial drama

Produced in Taiwan (Taiwan-mainland co-production)

Watch on Youtube here

Noteworthy: “The beginning of a genre”

In today’s TV drama environment of China, dramas that focus on life during the imperial era are ubiquitous, with titles from the Imperial Doctress to Story of Yanxi Palace being everywhere.

But when this drama aired in the early 1990s, it was something quite new. The Legend of Qianlong, also known with the English translation A Fanciful Account of Qianlong, tells the (fictional) stories of the Emperor Qianlong’s Tours of Southern China.

It was the beginning of a drama genre that turned out to be hugely popular, with many new television series focusing on emperors and empresses in their youth or their tumultuous lives during the height of their power (Barme 2012, 33). Perhaps, this 1991 series will always be a classic just because it was one of the first within its genre.

#13 The Legend of the White Snake (新白娘子传奇)

Year: 1992

Episodes: 50

Genre: Fantasy

Produced in Taiwan

Noteworthy: “One of the most replayed TV series”

As many of the classics in this list, this hit TV series is also based on a folk legend, namely that of Madame White Snakee, a mythical snake-like spirit who strives to be human, which is a source for many major Chinese operas, films.

The 1992 TV series stars Angie Chiu and Cecilia Yip. In 2016, it was still one of the most replayed TV series. Even on IMDB, it is rated with an 8.2.

#14 Beijinger in New York (北京人在纽约)

Year: 1993

Episodes: 21

Watch: YouTube

Buy novel (in English): Beijinger in New York

Noteworthy: “The first Chinese-language TV show to be shot in the United States”

The TV series Beijinger in New York, also known as A Native of Beijing in New York, based on the novel by Glen Cao (Cao Guilin), was a hit when it was first broadcasted broadcast nightly on CCTV and watched by millions of Chinese.

The story follows the immigrant life of cello player and Beijinger Wang Qiming (王起明), who arrives in New York in 1980 together with his wife, and begins working as a dishwasher the next day.

The TV series marks a first in several aspects. It was the first Chinese-language TV show to be shot in the United States, but it was also the first time ever for the production of a Chinese TV drama that a bank loan was used in order to make it possible (Bai 2007, 83); in other words, it also marks the start of a more commercialized TV drama environment. FYI: the bank loan that was used was a total of US$1.3 million.

#15 I Love My Family (我爱我家)

Year: 1993

Genre: Comedy

Episodes: 120

Directed by Ying Da (英达) et al

First episodes on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “First Mandarin-language sitcom”

I Love My Family (Wǒ ài wǒjiā) is one of China’s first popular sitcoms, and the first Mandarin-language and multi-camera sitcom, that aired from 1993 to 1994. It has since been rerun on local channels countless of times.

One of the show’s central stars is Wen Xingyu (文兴宇), who was a popular comedian and director in mainland China.

At the time of I Love My Family, sitcoms were mostly characterized by their low production cost; three episodes were made within five working days (Di 2008, 122).

#16 Justice Pao (包青天)

Year: 1993

Episodes: 236

Genre: Historical drama

Produced in Taiwan

Some episodes on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “From 15 to 236 episodes”

This series is themed around Bao Zheng (包拯), a government official who lived during China’s Song Dynasty, from 999 to 1062, and who was known for his extreme honesty and uprightness. Award-winning Taiwanese actor Jin Chao-chun (金超群) plays this role.

The series was originally scheduled for just 15 episodes, but was received so well when it aired on Chinese Television System, that it was eventually expanded to 236 episodes.

The story of Justice Bao is still a recurring topic in the popular culture of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. There was the 2008 Chinese series Justice Bao, and the 2010 New Justice Bao, that also starred Jin Chao-chun.

#17 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义)

Year: 1994

Episodes: 84

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Wang Fulin (王扶林)

Buy original novel here: The Romance of the Three Kingdoms

Some episodes available with English subtitles here.

Noteworthy: “400,000 people involved in the production”

This is another classic TV series produced by the CCTV, and that is also adapted from a classical novel (same title, written by Luo Guanzhong). Its director, Wang Fulin (王扶林), also directed the CCTV’s first TV drama Eighteen Years in the Enemy’s Camp, and A Dream of Red Mansions.

The production of Romance of the Three Kingdoms is especially noteworthy because the productions costs broke all kinds of records at the time; the production of the 84 one-hour episodes took four years, total costs were over 170 million RMB (±US$25 million), and around 400,000 people were involved – the larghest number of people involved in a production in the history of Chinese television. THe show has been watched by some 1,2 billion people around the world (Hongb 2007, 127).

#18 Heaven’s Above (苍天在上)

Year: 1995

Episodes: 17

Genre: Corruption drama (or ‘anti-corruption drama’ 反腐剧)

Directed by: Zhou Huan (周寰)

Noteworthy: “First drama about high-level official corruption”

In late 1995, the CCTV drama Heaven Above (Cāngtiān zài shàng) debuted on Chinese TV as the first TV series about high-level official corruption in the PRC.

It would certainly not be the last, as ‘corruption dramas’ became wildly popular – it is the entire focus of the 2014 book Staging Corruption by scholar Ruoyun Bai.

#19 Foreign Babes in Beijing (洋妞在北京)

Year: 1995

Genre: Urban drama

Episodes: 20

Noteworthy: “Foreign women in Chinese dramas”

Foreign Babes in Beijing (Yáng niū zài Běijīng) was one of the new kinds of dramas that featured foreigners in China. This series focues on two Chinese men and two American women, of which one seduces one of the Chinese (married) men. The show was a big hit in the mid-1990s.

One of the show’s actresses, Rachel Dewoskin, later wrote the recommended book Foreign Babes in Beijing: Behind the Scenes of a New China about her experiences of playing in the show and her life in China at the time.

#20 My Dear Motherland (我亲爱的祖国)

Year: 1999

Episodes: 21

Genre: History/War

Directed by: Liu Yiran (刘毅然)

Watch on Billibilli here, QQ, or on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “Rated with a 9.1”

This 1999 series is still rated with a 9.1 on Douban today. The series tells the experiences and hardships of three generations of Chinese intellectuals during the tumultuous (war)history of China’s 20th century, starting during the May Fourth Movement in 1919.

Chen Jianbin (陈建斌) is one of the famous actors starring in this TV drama as Fang Xuetong.

#21 Yongzheng’s Dynasty (雍正王朝)

Year: 1999

Episodes: 44

Genre: History/Costume

Noteworthy: “Qing drama as export product”

Yongzheng Dynasty is one of many so-called “Qing dramas” – TV dramas that focus on palace life during the 1644-1911 Qing Dynasty. According to scholar Zhu (2008), one of the reasons that dynasty dramas such as these became so enormously popular in mainland China is that (1) certain social and political issues can be discussed in the shape of stories and settings that are very much removed from modern-day China, allowing for more relaxed censorship policies on storylines and dialogues, and (2) that the reconstruction of “history” allows room for artistic interventions (22).

This epic TV drama was loosely based on historical events in the reigns of the Kangxi and Yongzheng Emperors, and became one of the most watched television series in mainland China of the 1990s. Also outside of China the show became very popular, making the so-called ‘Qing dramas’ an export product.

#22 Towards the Republic (走向共和)

Year: 2003

Episodes: 59 (one hour per episode)

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Zhang Li (张黎)

Watch on Youtube , buy on Amazon with English subtitles.

Noteworthy: “59 hours of historical drama”

This is one of the most important TV series in this list. On Sogou ratings, Towards the Republic, which is also known as For the Sake of the Republic (Zǒuxiàng gònghé), is one of netizens’ top all-time favorite series, rated with a 9.7.

The CCTV TV drama tells the story of the historical events in China from 1890 to 1917 – the time during which the Qing Dynasty collapsed, and the Republic of China (1912-1949) was founded. Important historical events such as the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the Hundred Days’ Reform (1898), the Boxer Rebellion (1900) and the Xinhai Revolution (1911) are all featured in this epic drama, that mainly focuses on the lives of Li Hongzhang (Chinese general in late Qing), Empress Dowager Cixi, Sun Yat-Sen, and Yuan Shikai.

The historical drama was not without controversy, and some parts of it have been censored in mainland China. The original series had 60 episodes, which was later brought down to 59. The TV drama has also been a fruitful topic for scholars for its representation of history. In the 2007 book Representing History in Chinese Media: The TV Drama Zou Xiang Gonghe (Towards the Republic) by Gotelind Mueller, the entire series is analyzed in how history is portrayed and narrated.

#23 Crimson Romance (血色浪漫)

Year: 2004

Episodes: 32

Genre Youth drama

Directed by: Teng Wenji (滕文骥)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Romantizing the Cultural Revolution”

There are almost 40,000 netizens ranking this 2004 TV drama on Douban, where it scores a 8.7.

The TV drama, which is also known as Romantic Life in English, dramatizes memories of the Cultural Revolution, focusing on a group of friends, their hopes and dreams, and their romantic life. It is set in Beijing in the late period of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

#24 Fu Gui (福贵)

Year: 2005

Episodes: 33

Genre: Family drama

Directed by Zhu Zheng (朱正)

Original novel: To Live: A Novel

Watch on Youtube.

Noteworthy: “Based on the novel To Live“

Chuang Chen (陈创), Liu Mintao (刘敏涛), and Li Ding (李丁) star in this family drama, which is ranked with a 9.4 on Sogou, and 4,5 stars or a 9,4 on Douban (more than 5500 voters).

The drama is based on the 1993 novel by Yu Hua (余华) To Live (活着), which focuses on the struggles of the son of a wealthy land-owner, Xu Fugui, amidst the tumultuous times of the Chinese Revolution. The story became well-known by the movie of the same title by Zhang Yimou, which became an international success.

#25 Ming Dynasty in 1566 (大明王朝1566)

Year: 2007

Episodes: 46

Genre: Historical drama

Directed by: Zhang Li (张黎)

Available with English subtitles on Youtube

Noteworthy: “Scoring a 9.7 on Douban, rated by 55,000 users”

Ming Dynasty in 1566 (Dàmíng wángcháo), starring Chinese actor Chen Baoguo (陈宝国), is a Chinese television series based on historical events during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor (1507-1567) of the Ming dynasty. It was first broadcast on Hunan TV in China in 2007.

On Douban, more than 55000 people have reviewed this movie at time of writing, coming up with a score of 9.7, one of the highest in this list. The drama was also broadcasted in other countries, such as South Korea.

#26 Dwelling Narrowness (蜗居)

Year: 2009

Episodes: 35

Genre: Urban Drama

Directed by: Teng Huatao (滕华涛)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “Focusing on China’s urban real estate bubble”

Also known as Snail House, this TV drama was all the rage back in 2009 for its focus on the crazy housing market in urban China and the lives of ordinary Chinese who are struggling to survive in the city while living in small spaces. Dwelling Narrowness, based on a novel by the same name, tells the story of two sisters with very different lifestyles who are looking to find a home in Shanghai (or actually, the fictional city of Jiangzhou, that basically represents Shanghai), and improve their quality of life, each in their own way.

The real estate bubble is a major theme throughout these series, and the TV drama was much-discussed within the frame of Chinese urban dwellers becoming “house slaves” (房奴). In the year of its broadcast, Wall Street Journal featured an article dedicated to the series and the discussions it triggered online.

#27 The Red (红色)

Year: 2014

Episodes: 48

Genre: War drama

Directed by Yang Lei (杨磊)

Noteworthy: “Patriotism as its key theme”

War drama The Red (Hóngsè) receives a 9.2 on Sogou, showing its success over the last four years.

Edward Zhang (Zhang Luyi 张鲁一) stars in this drama as an ordinary worker in Shanghai who gets caught up in underground circles at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and unexpectedly becomes part of a decisive moment in Chinese modern history. Perhaps unsurprinsginly, ‘Patriotism’ is a key theme throughout The Red.

#28 Moral Peanuts – Final Season (毛骗 终结篇)

Year: 2015

Episodes: 10 (in this season)

Genre: Crime/Suspense

Directed by: Li Hongchou (李洪绸)

Watch on Youtube here.

Noteworthy: “A gang of friends who con people out of their money”

Rated with a 9.6 on Sogou and a 9.6 by more than 26,000 people on Douban, this TV drama has already become somewhat of a classic in the few years since its airing.

Moral Peanuts is a multiple season series (started in 2010), that follows a gang of five young friends who live together and earn their living in a fraudulent way. The series is characterized by its cliffhanger endings and its ‘grey’ portrayals of its characters.

#29 In the Name of the People (人民的名义)

Year: 2017

Episodes: 55

Genre: Corruption drama

Directed by: Li Lu

Available with English subtitles here.

Noteworthy: “The Chinese ‘House of Cards'”

In the Name of the People is a 2017 highly popular Chinese TV drama series based on the web novel of the same name by Zhou Meisen (周梅森). Its plot revolves around a prosecutor’s efforts to unearth corruption in a present-day fictional Chinese city by the name of Jingzhou.

In 2017, this TV drama became a true craze on Chinese social media and received a lot of coverage in (international) media for being comparable to the American political drama House of Cards. The BBC described it as “the latest piece of propaganda aimed at portraying the government’s victory in its anti-corruption campaign.”

#30 White Deer Plain (白鹿原)

Year: 2017

Genre: Contemporary historical drama

Episodes: 85

Directed by: Liu Jin (刘进)

WAtch with English subs at New Asian TV here.

Noteworthy: “The epic TV drama took nearly 17 years to prepare and produce “

This TV drama has consistently been ranking number one in Baidu’s and Weibo’s popular drama charts last year, and is now ranked with an 8.8 score on sites such as Douban. Although it is somewhat tricky to call such a present-day drama a ‘classic’, we’ll take the chance.

White Deer Plain is based on the award-winning Chinese literary classic by Chen Zhongshi (陈忠实) from 1993. The preparation and production of this series reportedly took a staggering 17 years and a budget of 230 million yuan (US$33.39 million).

The success of the novel this TV drama is based on, has previously been compared to that of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez. White Deer Plain follows the stories of people from several generations living on the ‘White Deer Plain,’ or North China Plain in Shaanxi province, during the first half of the 20th century. This tumultuous period sees the Republican Period, the Japanese invasion, and the early days of the People’s Republic of China. The series is great in providing insights into how people used to live, from dress to daily life matter. The scenery and sets are beautiful.

Some Book Recommendations Based on This List:

* Chinese Television in the Twenty-First Century: Entertaining the Nation (Routledge Contemporary China Series Book 121)

* Staging Corruption: Chinese Television and Politics (Contemporary Chinese Studies)

* Television in Post-Reform China: Serial Dramas, Confucian Leadership and the Global Television Market (Routledge Media, Culture and Social Change in Asia)

* TV Drama in China (TransAsia: Screen Cultures)

* Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis

Want to know more? Check out our various Top 10s of popular Chinese TV Dramas from 2013 to present here.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

*1(We kindly ask not to reproduce this list without permission – please link back if referring to it).

References

Bai, Ruoyun. 2007. “TV Dramas in China – Implications of the Globalization.” In Manfred Kops and Stefan Ollig (eds), Internationalization of the Chinese TV sector, 75-99. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

Bai, Ruoyun. 2014. Staging Corruption: Chinese Television and Politics. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Barmé, Geremie. 2012. “Red Allure and the Crimson Blindfold.” China Perspectives, 2012/2, 29-40.

Di, Miao. 2008. “A Brief History of Chinese Situation Comedies.” In Ruoyun Bai, Ying Zhu, Michael Keane (eds), TV Drama in China, 117-129. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Hong, Junhao. 2007. “The Historical Development of Program Exchange in the TV Sector.” In Manfred Kops and Stefan Ollig (eds), Internationalization of the Chinese TV sector, 25-40. Berlin: LIT Verlag.

–. 2007b. “From Three Kingdoms the Novel to Three Kingdoms the Television Series: Gains, Losses, and Implications.” In Kimberly Besio and Constantine Tung (eds), Three Kingdoms and Chinese Culture, 125-143. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Zhu, Ying. 2008. “Yongzheng Dynasty and Totalitarian Nostalgia.” In Bai R, Keane M, Zhu Y. (eds), TV Drama in China, 21-33. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press; 2008

Wang, Min and Arvind Singhal. 1992. “Kewang, A Chinese Television Soap Opera With A Message.” Gazette 49: 177-192.

Directly support Manya Koetse. By supporting this author you make future articles possible and help the maintenance and independence of this site. Donate directly through Paypal here. Also check out the What’s on Weibo donations page for donations through creditcard & WeChat and for more information.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us.

©2018 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Arts & Entertainment

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

“I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like listening to Alicia Keys.” Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers.

Published

2 months agoon

May 17, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

Besides memes and jokes, Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers on Chinese social media.

In May, while the whole of Europe was gripped by the Eurovision Song Contest frenzy, Chinese audiences were eagerly anticipating the return of their own beloved singing competition, Singer 2024 (@湖南卫视歌手), formerly known as I Am a Singer (我是歌手).

The show, introduced from South Korea’s MBC Television and popular in China since 2013, only features professional singers who have already made a name for themselves.

Rather than watching unknown aspiring singers who are hoping to be discovered in many singing competitions, such as Sing! China, Singer 2024 gives audiences a show filled with professional and often stunning show performances by established names in the entertainment industry.

Since 2013, renowned singers from China and abroad have appeared on the show, including Chinese vocalist Tan Jing (谭晶), British pop singer Jessie J, and the late Hong Kong pop diva Coco Lee. However, no season managed to create as many waves as the 2024 season did, dominating all social media trending topics overnight.

So, what exactly happened?

COMPETING WITH FOREIGNERS

“The difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival”

In early May, the pre-show promotion of Singer 2024 was already buzzing on Chinese social media after a list of featured singers appeared on Weibo, including big names such as American singer-songwriter Bruno Mars, Korean-New Zealand singer Rosé from Blackpink, and Japanese diva LiSA.

Although Singer previously had many foreign singers on the show, this international celebrity lineup still caused a stir.

On the day of the first episode, only two foreign singers were announced to appear on the show: young Moroccan-Canadian singer Faouzia and the Grammy-nominated American singer-songwriter Chanté Moore. The other contestants were all Chinese singers who are already well-known among Chinese audiences. Because many people were unfamiliar with the two foreign singers, they joked that the winner of this season was already set in stone; surely it would be the famous Chinese singer Na Ying (那英), known for her beautiful voice.

However, that first episode surprised everyone as the two foreign singers, Faouzia and Chanté Moore, showed outstanding vocal skills. This not only startled many viewers but also made the Chinese contestants uneasy. Several experienced Chinese singers apparently were so unnerved after watching Faouzia and Chanté Moore’s performance that their voices trembled when singing.

Since the show was broadcast live – without post-production editing or autotune – audiences got to hear the actual vocal capabilities and see performers’ genuine reactions. It seemed undeniable that the foreign contestants did much better in terms of vocals and stage presence than the Chinese ones. Some online commenters even said that the gap between Chinese and foreign singers’ levels was like “the difference between the Grammys and the Strawberry Musical Festival” [a local Chinese music festival].

Chinese online influencer Yongkai (@陈咏开165) shared screenshots of Chanté Moore’s backstage reactions during the show. The American celebrity seemed puzzled when hearing the somewhat underwhelming performance by Chinese singer Yang Chenglin (楊丞琳), and she appeared much more positive when Na Ying sang.

This noteworthy scene, coupled with Chanté’s comments during an interview saying that she thought the Chinese production team had invited her on the show to be a judge, turned the entire show into a display of foreign singers outshining the Chinese contestants.

By the end of the first episode, Chanté Moore and Faouzia unsurprisingly ranked first and second, with Na Ying in third place.

After the show, some online commenters jokingly pointed out that Na Ying, being of Manchu descent like the rulers of China during the Qing Dynasty, showed some similarities to Empress Dowager Cixi’s defiance against Western colonizers in the way she “single-handedly took up against on foreigners” on the show.

They humorously turned Na Ying’s expressions into memes resembling Empress Dowager Cixi from an old Chinese TV show, with captions like “I want the foreigners dead” (“我要洋人死”).

Others suggested finding better Chinese singers for the show who could compete with Faouzia and Moore.

“SINGING WELL” CULTURALLY COLONIZED?

“I’m in Zibo eating BBQ, I really don’t want to listen to Alicia Keys.”

Initially, discussions about the show were light-hearted and humorous, until some netizens who couldn’t appreciate the jokes began to dampen the mood and made online discussions more serious.

Zou Xiaoying (@邹小樱), a music critic with nearly two million followers, posted on social media after the show, stating that he would have never voted for Chanté Moore or Faouzia. Not only did Zou question their vocal talent, he also wondered if the aesthetic of Chinese listeners had been influenced by Western music taste to such an extent that it has been “culturally colonized” (“文化殖民”). Meanwhile, he praised the members of Beijing rock band Second Hand Rose as “national heroes” (“民族英雄”).

He wrote:

If I had three votes for the first episode of “Singer 2024,” I’d vote for Second Hand Rose, Na Ying, and Silence Wang [note: Chinese singer-songwriter and record producer Wang Sushuang 汪苏泷]. The reason I wouldn’t vote for Chanté Moore or Faouzia is because — do they actually sing so well?

Has our definition of “singing well” perhaps been colonized? Just as our modern-day use of Chinese has little to do with our classical Chinese poems, with the foundation of modern Chinese actually being translations from the 20th century, is this also a form of ‘cultural colonization’?

You must think I’m talking nonsense again. But when I listen to Chanté Moore singing “If I Ain’t Got You,” I find it too boring. I know her singing is “good,” but this “good” has nothing to do with me. If, for Chinese listeners, Chanté Moore’s “good” is the standard, then is that what we in the music industry should be working towards? Isn’t that funny? When you open QQ Music or NetEase Cloud Music, and it recommends these songs to you every day, won’t you be convinced to practice again?

Of course, I know Chanté Moore is in good shape, very relaxed. Actually all of the Chinese singers tonight were very nervous. Yang Chenglin (杨丞琳) was nervous, Na Ying was also nervous. Even a seemingly carefree band like Second Hand Rose, if you listened to the introduction of their song, [you’ll find] they were so nervous that Yao Lan, supposedly “China’s No.1 Guitarist”, was so nervous that he hit the wrong note. It was not even a fast-paced solo (…), how nervous could he be? When everyone’s so tense, the confidence of Chanté Moore and Faouzia is indeed something that East Asia can’t match. In East-Asian [entertainment] circles, represented by China/Japan/Korea, our different cultural habits, upbringing, and ethnic characteristics have made it so that we don’t possess these kinds of singing abilities, even including our ways of emotional expression. I don’t know from which season it started with ‘Singer’ – and if it’s some kind of Catfish Effect (鲶鱼效应 ) – that they brought international singers with different cultural backgrounds into the competition. But this isn’t the Olympics, it’s not like Liu Xiang [刘翔, Chinese gold medal hurdler] is going to defeat opponents from the United States or Cuba. “I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like Alicia Keys.” (This line is not mine, I stole it from my WeChat friend).

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Because of this, I find Second Hand Rose even more rare and precious. It’s just like I used to love asking: If you could only recommend one Chinese band to your foreign friends, which one would you recommend? Some say it’s New Pants (新裤子), some say it’s Omnipotent Youth Society, but my answer will always be Second Hand Rose. ‘The drama of Monkey King is a national treasure,’ its light will always shine. Facing the gunfire of Western powers, Second Hand Rose is standing on the frontline, they are our national heroes. Indeed, the band itself was nervous, (..), but when Chanté Moore goes off like a singing dolphin, we are fortunate to have Second Hand Rose at the frontline; the Chinese sons and daughters are building the Great Wall of Music of flesh and blood.

Anyway, no matter if they’re strong or not, I would never vote for the foreigner.

The comment about ‘I’m in Zibo eating barbecue, I really don’t feel like [listening to] Alicia Keys’ refers to the craze surrounding China’s ‘BBQ town’ Zibo. In Zibo, Chinese visitors like to sing, drink beer, and enjoy food together; it’s a simple and modest way of appreciating life and music, which contrasts with slick and smooth American or foreign styles of performing and singing.

Whether Zou’s criticism was for attention or genuine sentiment, it shifted the focus of the discussion from music to patriotism.

CHINESE SINGERS WITH MILITARISTIC UNDERTONES

“I volunteer to join the battle”

Amidst all this, some netizens, easily swayed by nationalist sentiments, began to seek help from the “national team” (国家队) of singers — musicians employed by national-level arts troupes — to “bring glory to the nation” and teach the foreigners a lesson. Some even questioned the intentions of the Singer 2024 TV show in inviting foreign singers to participate.

On May 12th, renowned Chinese singer and philanthropist Han Hong (韩红) posted on Weibo, fueling a wave of sentiment and support. In her post, Han Hong declared, “I am Chinese singer Han Hong, and I volunteer to join the battle,” tagging the production team of the TV show. Her invitation to join the battle quickly went viral.

Han Hong meme: “Who called for me?”

Han Hong has significant influence in the Chinese music industry and society as a whole. Her usual serious demeanor and avoidance of internet pop culture made netizens unsure whether she was joking or serious. Nevertheless, regardless of her intentions, a group of well-known singers began to volunteer via Weibo, emphasizing their identity as “Chinese singers” and using phrases with strong militaristic undertones like “fighting for the country” and “answering the call.”

Although many enjoyed this new wave of national pride in Chinese music and performers, some netizens criticized the trend of transforming an entertainment show into a nationalistic competition.

Film critic He Xiaoqin (何小沁) stated, “It’s okay to take the Qing-Dynasty-fighting-foreigners comparison as a joke, but taking it too seriously in today’s context is absurd.”

Others expressed fatigue with how quickly topics on Chinese internet platforms escalate to patriotic sentiments. To bring the focus back to entertainment, they turned “I volunteer to join the battle” (#我请战#) into a new internet catchphrase.

In response, the production team of Singer 2024 released a statement on Weibo, thanking all the singers for their self-recommendations. They emphasized the show’s competitive structure but clarified that “winning” is just one part of a singer’s journey..but that the love of music goes beyond all in connecting people, no matter where they’re from.

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Arts & Entertainment

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

Online reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among Chinese netizens.

Published

3 months agoon

April 18, 2024

The recent marriage announcement of the renowned Chinese calligrapher/painter Fan Zeng and Xu Meng, a Beijing TV presenter 50 years his junior, has sparked online discussions about the life and work of the esteemed Chinese artist. Some netizens think Fan lacks the integrity expected of a Chinese scholar-artist.

Recently, the marriage of a 86-year-old Chinese painter to his bride, who is half a century younger, has stirred conversations on Chinese social media.

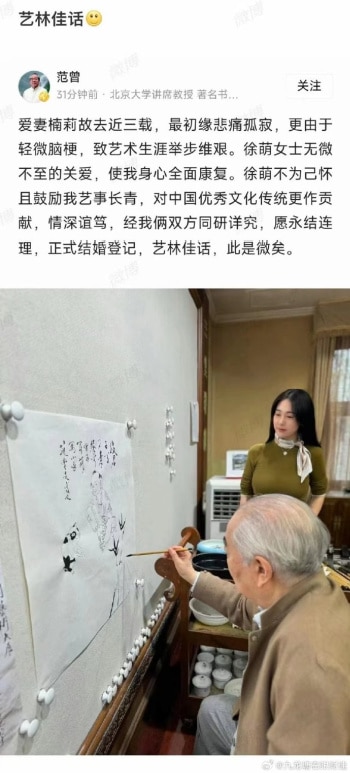

The story revolves around renowned Chinese artist, calligrapher, and scholar Fan Zeng (范曾, 1938) and his new spouse, Xu Meng (徐萌, 1988). On April 10, Fan announced their marriage through an online post accompanied by a picture.

In the picture, Fan is seen working on his announcement in calligraphic form.

Fan Zeng announces his marriage on Chinese social media.

In his writing, Zeng shares that the passing of his late wife, three years ago, left him heartbroken, and a minor stroke also hindered his work. He expresses gratitude for Xu Meng’s care, which he says led to his physical and mental recovery. Zeng concludes by expressing hope for “everlasting harmony” in their marriage.

Fan Zeng is a calligrapher and poet, but he is primarily recognized as a contemporary master of traditional Chinese painting. Growing up in a well-known literary family, his journey in art began at a young age. Fan studied under renowned mentors at the Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, including Wu Zuoren, Li Keran, Jiang Zhaohe, and Li Kuchan.

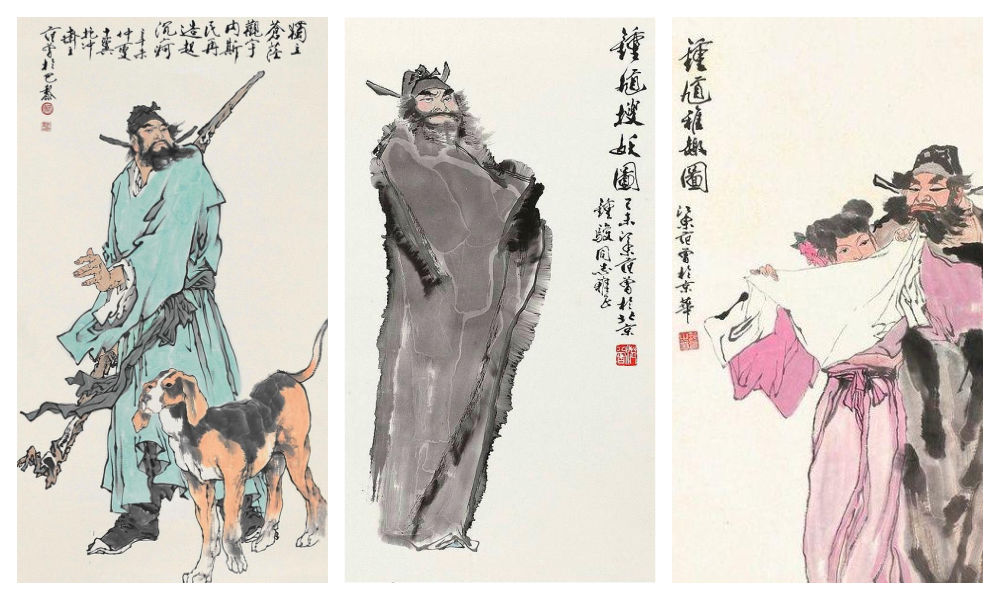

Fan gained global acclaim for his simple yet vibrant painting style. He resided in France, showcased his work in numerous exhibitions worldwide, and his pieces were auctioned at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in the 1980s.[1] One of Fan’s works, depicting spirit guardian Zhong Kui (钟馗), was sold for over 6 million yuan (828,000 USD).

Zhong Kui in works by Fan Zeng.

In his later years, Fan Zeng transitioned to academia, serving as a lecturer at Nankai University in Tianjin. At the age of 63, he assumed the role of head of the Nankai University Museum of Antiquities, as well as holding various other positions from doctoral supervisor to honorary dean.

By now, Fan’s work has already become part of China’s twentieth-century art history. Renowned contemporary scholar Qian Zhongshu once remarked that Fan “excelled all in artistic quality, painting people beyond mere physicality.”

A questionable “role model”

Fan’s third wife passed away in 2021. Later, he got to know Xu Meng, a presenter at China Traffic Broadcasting. Allegedly, shortly after they met, he gifted her a Ferrari, sparking the beginning of their relationship.

A photo of Xu and her Hermes Birkin 25 bag has also been making the rounds on social media, fueling rumors that she is only in it for the money (the bag costs more than 180,000 yuan / nearly 25,000 USD).

On Weibo, reactions to the news of Fan’s marriage to Xu Meng, his fourth wife, reveal that the renowned artist is not particularly well-liked among netizens. Despite Fan’s reputation as a prominent philanthropist, many perceive his recent marriage as yet another instance of his lack of integrity and shamelessness.

Fan Zeng and Xu Meng. Image via Weibo.

One popular blogger (@好时代见证记录者) sarcastically wrote:

“Warm congratulations to the 86-year-old renowned contemporary erudite scholar and famous calligrapher Fan Zeng, born in 1938, on his marriage to Ms Xu Meng, a 50 years younger 175cm tall woman who is claimed to be China’s number one golden ratio beauty. Mr Fan Zeng really is a role model for us middle-aged greasy men, as it makes us feel much less uncomfortable when we’re pursuing post-90s youngsters as girlfriends and gives us an extra shield! Because if contemporary Confucian scholars [like yourself] are doing this, then we, as the inheritors of Confucian culture, can surely do the same!“

Various people criticize the fact that Xu Meng is essentially just an aide to Fan, as she can often be seen helping him during his work. One commenter wrote: “Couldn’t he have just hired an assistant? There’s no need to turn them into a bed partner.”

Others think it’s strange for a supposedly scholarly man to be so superficial: “He just wants her for her body. And she just wants him for his inheritance.”

“It’s so inappropriate,” others wrote, labeling Fan as “an old bull grazing on young grass” (lǎoniú chī nèncǎo 老牛吃嫩草).

Fan is not the only well-known Chinese scholar to ‘graze on young grass.’ The famous Chinese theoretical physicist Yang Zhenning (杨振宁, 1922), now 101 years old, also shares a 48-year age gap with his wife Weng Fen (翁帆). Fan, who is a friend of Yang’s, previously praised the love between Yang and Weng, suggesting that she kept him youthful.

Older photo posted on social media, showing Fan attending the wedding ceremony of Yang Zhenning and his 48-year-younger partner Weng Fen.

Some speculate that Fan took inspiration from Yang in marrying a significantly younger woman. Others view him as hypocritical, given his expressions of heartbreak over his previous wife’s passing, and how there’s only one true love in his lifetime, only to remarry a few years later.

Many commenters argue that Fan Zeng’s conduct doesn’t align with that of a “true Confucian scholar,” suggesting that he’s undeserving of the praise he receives.

“Mr. Wang from next door”

In online discussions surrounding Fan Zeng’s recent marriage, more reasons emerge as to why people dislike him.

Many netizens perceive him as more of a money-driven businessman rather than an idealistic artist. They label him as arrogant, critique his work, and question why his pieces sell for so much money. Some even allege that the only reason he created a calligraphy painting of his marriage announcement is to profit from it.

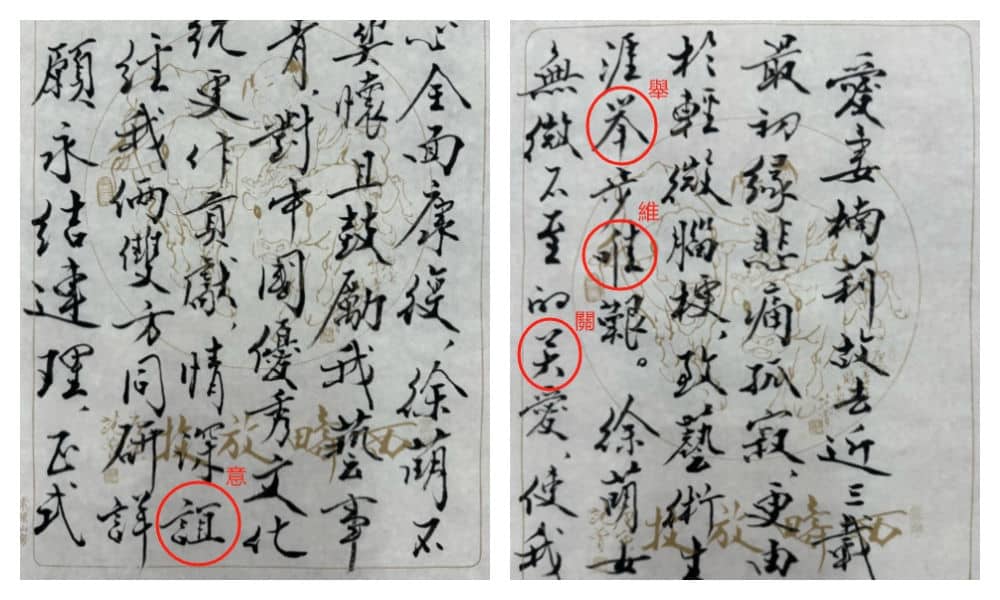

Others cast doubt on his status as a Chinese calligraphy ‘grandmaster,’ noting that his calligraphy style is not particularly impressive and may contain typos or errors. His wedding announcement calligraphy appears to blend traditional and simplified characters.

Netizens have pointed out what looks like errors or typos in Fan’s calligraphy.

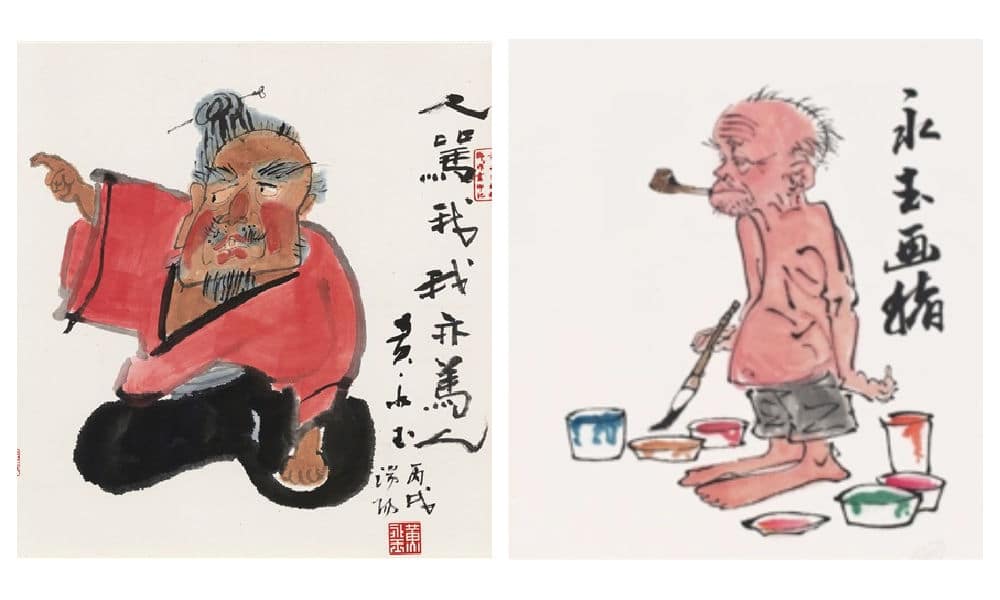

Another source of dislike stems from his history of disloyalty and his feud with another prominent Chinese painter, Huang Yongyu (黄永玉). Huang, who passed away in 2023, targeted Fan Zeng in some of his satirical paintings, including one titled “When Others Curse Me, I Also Curse Others” (“人骂我,我亦骂人”). He also painted a parrot, meant to mock Fan Zeng’s unoriginality.

Huang Yongyu made various works targeting Fan Zeng.

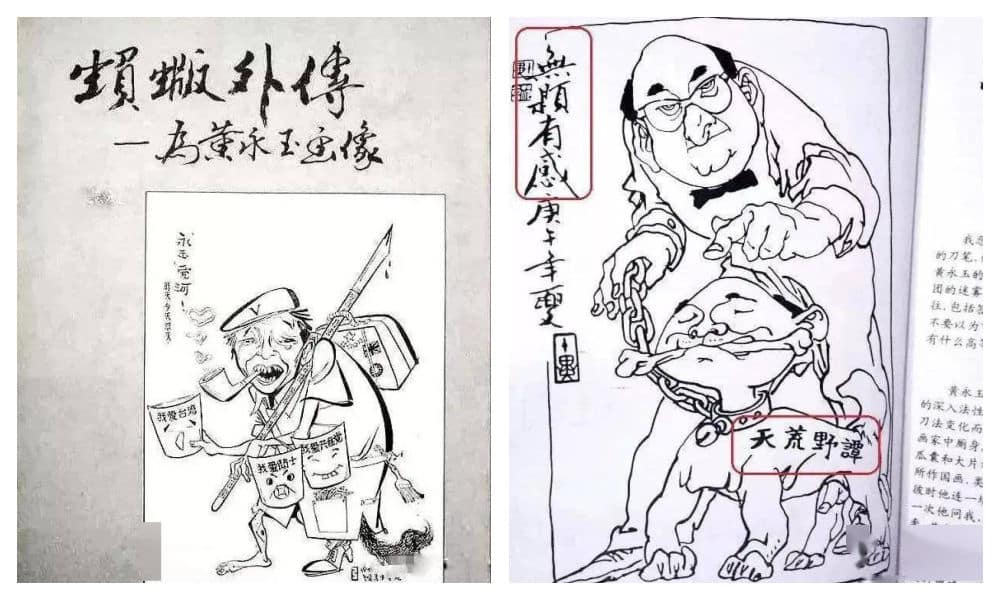

In retaliation, Fan produced his own works mocking Huang, sparking an infamous rivalry in the Chinese art world. The two allegedly almost had a physical fight when they ran into each other at the Beijing Hotel.

Fan Zeng mocked Huang Yongyu in some of his works.

Fan and Huang were once on good terms though, with Fan studying under Huang at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Through Huang, Fan was introduced to the renowned Chinese novelist Shen Congwen (沈从文, 1902-1988), Huang’s first cousin and lifelong friend. As Shen guided Fan in his studies and connected him with influential figures in China’s cultural circles, their relationship flourished.

However, during the Cultural Revolution, when Shen was accused of being a ‘reactionary,’ Fan Zeng turned against him, even going as far as creating big-character posters to criticize his former mentor.[2] This betrayal not only severed the bond between Shen and Fan but also ended Fan’s friendship with Huang, and it is still remembered by people today.

Fan Zeng’s behavior towards another former mentor, the renowned painter Li Kuchan (李苦禪, 1899-1983), was also controversial. Once Fan gained fame, he made it clear that he no longer respected Li as his teacher. Li later referred to Fan as “a wolf in sheep’s clothes,” and apparently never forgave him. Although the exact details of their falling out remain unclear, some blame Fan for exploiting Li to further his own career.

There are also some online commenters who call Fan Zeng a “Mr Wang from next door” (隔壁老王), a term jokingly used to refer to the untrustworthy neighbor who sleeps with one’s wife. This is mostly because of the history of how Fan Zeng met his third wife.

Fan’s first wife was the Chinese female calligrapher Lin Xiu (林岫), who came from a wealthy family. During this marriage, Fan did not have to worry about money and focused on his artistic endeavours. The two had a son, but the marriage ended in divorce after a decade. Fan’s second wife was fellow painter Bian Biaohua (边宝华), with whom he had a daughter. It seems that Bian loved Fan much more than he loved her.

It is how he met his third wife that remains controversial to this day. Nan Li (楠莉), formerly named Zhang Guiyun (张桂云), was married to performer Xu Zunde (须遵德). Xu was a close friend of Fan, and helped him out when Fan was still poor and trying to get by while living in Beijing’s old city center.

Wanting to support Fan’s artistic talent, Xu let Fan Zeng stay over, supported him financially, and would invite him for meals. Little did he know that while Xu was away to work, Fan enjoyed much more than meals alone; Fan and Xu’s wife engaged in a secret decade-long affair.

When the affair was finally exposed, Xu Zunde divorced his wife. Still, they would use his house to meet and often locked him out. Three years later, Nan Li officially married Fan Zeng. Xu not only lost his wife and friend but also ended up finding his house emptied, his two sons now bearing Fan’s surname.

When Nan Li passed away in 2021, Fan Zeng published an obituary that garnered criticism. Some felt that the entire text was actually more about praising himself than focusing on the life and character of his late wife, with whom he had been married for forty years.

Fan Zeng and his four wives

An ‘old pervert’, a ‘traitor’, a ‘disgrace’—there are a lot of opinions circulating about Fan that have come up this week.

Despite the negativity, a handful of individuals maintain a positive outlook. A former colleague of Xu Meng writes: “If they genuinely like each other, age shouldn’t matter. Here’s to wishing them a joyful marriage.”

By Manya Koetse

[1]Song, Yuwu. 2014. Biographical Dictionary of the People’s Republic of China. United Kingdom: McFarland & Company, 76.

[2]Xu, Jilin. 2024. “Xu Jilin: Are Shen Congwen’s Tears Related to Fan Zeng?” 许纪霖:沈从文的泪与范曾有关系吗? The Paper, April 15. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_27011031. Accessed April 17, 2024.

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

Ben

November 16, 2018 at 10:33 am

In the picture for “#18 Heaven’s Above (苍天在上)”, the character seems to be holding a smartphone – possibly an iPhone given what looks to be an apple on the back side. That would be anachronistic for a 1995 series I think?

Admin

November 16, 2018 at 10:41 am

Well spotted, Ben! You’re right! That was an image from a modern remake mini-series of Heaven’s Above (苍天在上), not the 1995 version. We’ve now replaced with an image from the original show. Thanks for the heads up 🙂

autraka

November 22, 2018 at 6:59 am

Wish you included 武林外传、还珠格格 and more TV dramas based on 金庸‘s novels.

Brown

January 2, 2019 at 10:58 am

Chinese TVs set in Qing Dynasty are an amazing series for me. I love the Story of Yanxi Palace especially. I have found the top 10 related Qing Dynasty TVs from here

https://chinausual.com/top-10-chinese-tv-series-set-in-qing-dynasty/

Jason

February 23, 2019 at 9:57 am

Actually “White Deer Plain” 白鹿原 is in Shaanxi(陕西). Not Shanxi(山西)。