China Health & Science

We Want Milk! Australian Baby Formula Sold Out Due to Chinese Demand

A great demand for milk powder in mainland China has lead to baby formula shortages in different countries. Now, the shelves in Australia are empty.

Published

9 years agoon

The great demand for milk powder in mainland China has led to baby formula shortages in different countries. The major milk shopping spree on China’s Singles Day has now left the shelves in Australia empty. The milk shortages lead to heated online discussions, both in Australia and in China.

Unofficial Chinese exporters are busier than ever buying baby formula in Australian supermarkets and pharmacies to ship to China. It is a highly lucrative market for them: the average price for a tin of milk powder is AUD 25 (±18 US$), but Chinese mums are willing to pay up to AUD 80-100 (58-72 US$) per tin.

Due to the high demand of baby powder in China, Australian-based Chinese, especially international students, frantically buy boxes of milk powers to sell to their Chinese contacts. It has left shelves empty in local supermarkets, triggering the anger of Australian mums.

“Some parents have to visit up to 15 different supermarkets and pharmacies before they can buy milk powder for their baby.”

The demand for milk powder recently intensified in the lead-up to Singles Day, China’s biggest shopping day of the year. It has become hard to find baby formula in many of Melbourne supermarkets such as Coles or Woolworths. Popular baby formula brands including Bellamy’s, Karicare or A2 Platinum have become particularly difficult to obtain. According to Australian news reports, some parents have to visit up to 15 different supermarkets and pharmacies before they can buy milk powder for their baby.

One furious parent reportedly was so fed up with the situation, that she snapped pictures of two women buying 50 cans of A2 Platinum baby formula at a Melbourne supermarket, and uploaded them to Facebook. “My blood was boiling for the mothers having problems finding A2 for their babies. I was feeling sensitive because I’ve got a newborn,” the woman told Fairfax Media.

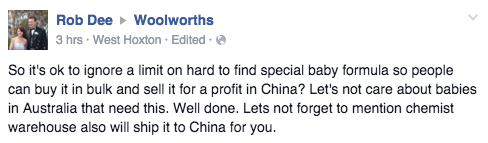

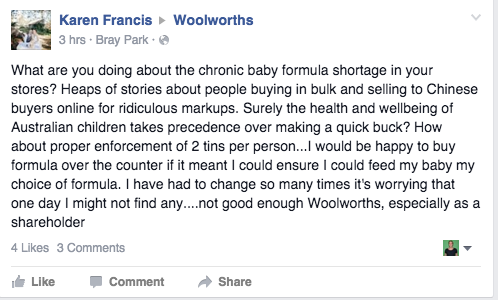

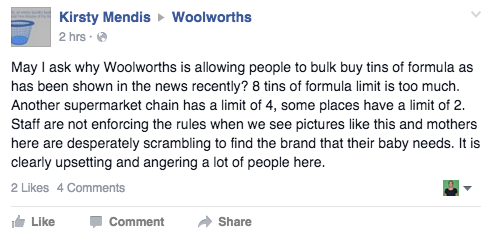

The pictures sparked heated discussions on Facebook (comment screenshots by Esposito & Fu, 2015).

As Chinese media reported on the issue, the shortage of baby formula in Australia also became a much-discussed topic on Sina Weibo under the hashtag of “Australian Milk powder Shortage” (#澳洲奶荒#) and “Australian Mums Hate Singles Day” (#澳洲妈妈最恨双11#).

“20 million babies are born in China every year, and only a quarter of them are breastfed.”

The reason that so many Chinese parents are buying baby formula from overseas dates back to the disastrous melamine poisoning cases that affected 300,000 Chinese babies in 2008. Many Chinese no longer trust Chinese manufactured milk powder. They therefore look to buy “clean and green” baby formula from countries such as Australia, The Netherlands, New Zealand or Hong Kong. Richer parents are willing to pay as much as five times the retail price for a tin of baby formula. For those who do not have the money, however, made-in-China formula is the only option.

With 20 million babies born in China every year, and only a quarter of them being breastfed, the demand for baby formula is growing rapidly.

Supermarkets and pharmacies in The Netherlands have already limited individual sales of baby formula: every customer can now only purchase one pack of baby formula from brands such as Nutrilon. In some Amsterdam pharmacies, an ID registration is required to purchase milk powder in order to avoid the same person buying different packs in different stores across the city. Some stores of supermarket chain Jumbo has set a rule that people can only buy milk powder if they spend at least 25 euro (±26 US$) on other groceries. It keeps unofficial exporters away.

Due to empty shelves, Nutrilon has now made it possible for Dutch citizens to order milk power online, with a limit of two packs a week.

The sales limits have made it more difficult for unofficial sellers to obtain large amounts of milk powder, making countries such as Australia a more attractive place to buy and sell baby formula.

“The penalty for unlicensed export of milk powder is up to 12 months imprisonment.”

When you search for “Australia buyers” (澳洲代购) on Taobao, Weibo or WeChat, thousands of results pop up. Chinese people living overseas make huge profits in purchasing commodities for their customers in mainland China.

Even Australian souvenir shops operated by Chinese have now turned to the ‘grey market’, with boxes of formula stacked up. While supermarkets are running out of formula, courier companies have so many parcels of formula in stock that they almost reach the roof, ready to be shipped overseas.

Several retailers including Woolworths and some pharmacies have now also introduced purchase limits to 2 tins of baby formula per customer.

In response to the massive import of milkpowder, the Australian Department of Agriculture and Water Resources issued an online statement this month, warning unofficial exporter that the penalty for unlicensed export of milk powder is up to 12 months imprisonment.

[learn_more caption=”Statement by the Australian Department”] “The Department of Agriculture and Water Resources understands that the community may have concerns about shortages of infant formula on Australian supermarket shelves.

The department understands supermarkets are taking measures to make sure adequate stock of infant formula are available and have been talking to their suppliers. These are commercial arrangements between retailers and the manufacturers of infant formula. The role of this department is to ensure goods exported comply with the Export Control Act 1982, meet foreign government requirements, are safe and accurately described. The penalty for failing to comply with the conditions of export orders—including exporting a prescribed dairy product without an export permit and sourcing from an unregistered establishment—is up to 12 months imprisonment. If the exporter also provides false information to an authorised officer the penalty is up to 5 years imprisonment.

Background

Exports of Australian-made infant formula to China that are over 10 kg (or 10 L liquid) must be sourced from registered export establishments and export documentation is only provided where export consignments comply with China’s requirements. that the penalty for failing to comply with the conditions of export orders—including exporting a prescribed dairy product without an export permit and sourcing from an unregistered establishment—is up to 12 months imprisonment. If the exporter also provides false information to an authorised officer the penalty is up to 5 years imprisonment. Exports of Australian-made infant formula to China that are over 10 kg (or 10 L liquid) must be sourced from registered export establishments and export documentation is only provided where export consignments comply with China’s requirements.”[/learn_more]

“The government has to think about why the majority of people have no trust in the milk produced here”

On Sina Weibo, netizen Elynpao urges Chinese to think about the issue of Australian baby formula shortage: “We have enough milk in China to supply our own people. Why should we burden such a big country [as Australia], causing them to scold Chinese businessmen for earning money like that? China should really reflect on itself.”

Another Weibo netizen named MELIFE also says that it is a shame how Chinese buy up all baby formula from Australian supermarkets and sell it to China just to earn money, leaving the local babies without any supplies.

“The government has to think about why the majority of people have no trust in the milk produced here,” another user comments. “It’s a national humilition,” another commenter says: “If a country cannot even safeguard the milk for its babies, making people go abroad for it; it’s really dreadful.”

– by Jennifer Tang

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

featured image: http://news.china.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/640-1059.jpeg

©2015 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

About the author: Jennifer is a freelance writer, translator and teacher from Hong Kong.

China Food & Drinks

Chinese Woman with Heartbreak Passes Away after Drinking Bottle of Baijiu

Three friends are held partially responsible for not intervening when the woman consumed 500ml of baijiu.

Published

7 months agoon

December 15, 2023

An incident that happened on the night of May 21, 2023, has become a trending topic on Chinese social media today after a local court examined the case.

A woman named ‘Xiao Qiu’ (alias), a resident of Jiangxi’s Nanchang, apparently attempted to drink her sorrows away after a heartbreaking breakup.

She spent the night at a friend’s house, where she drank about 50cl of baijiu (白酒), a popular Chinese spirit distilled from fermented sorghum that contains between 35% and 60% alcohol. One entire bottle of baijiu, such as Moutai, is usually 50cl.

She was together with three female friends. One of them also consumed baijiu, although not as much, and the two other friends did not drink at all.

As reported by Jiupai News, the intoxicated Xiao Qu ended up sleeping in her car, while one of her sober friends stayed with her. However, at about 5 AM, her friend discovered that Xiao Qiu was no longer breathing. Just about an hour later, she was declared dead at the local Emergency Center. The cause of death was ruled as cardiac and respiratory failure due to alcohol poisoning.

The court found that Xiao Qu’s friends were partly responsible for her death, citing their failure to prevent her excessive drinking and inadequate assistance following her baijiu binge drink session. Each friend was directed to contribute to the compensation for medical expenses and pain and suffering incurred by Qiu’s family.

The friend who also consumed baijiu was assigned a 6% compensation responsibility, while the other two were assigned 3% each.

On Weibo, many commenters do not agree with the court’s decision, asserting that adult individuals should not be held accountable when a friend goes on a drinking spree. Some commenters wrote: “You can tell someone not to drink, but what if they don’t listen?” “Should we record ourselves telling friends not to drink too much from now on?”

This is not the first time for friends to be held liable for an alcohol-related death in China. In 2018, multiple stories went viral involving people who died after excessive drinking at social gatherings.

One case involved a 30-year-old Chinese man who was found dead in his hotel room bathtub in Yangzhou after a formal dinner with friends where he allegedly drank heavily. The man reportedly died of a heart attack. His friends reached a 1 million yuan (±US$157,000) settlement with his family, with the cost shared among the friends who were present during the night.

Surveillance cameras in Jinhua captured how the man was unable to stand or walk after drinking with his friends.

Another case involved a man who died when he was left by his friends at a hotel in Jinhua, Zhejiang province, after heavily drinking at a banquet. Surveillance cameras captured how the man was unable to stand or walk after drinking with his friends. Those friends also paid a compensation together of 610,000 yuan (US$96,000) to the man’s family.

Organisers of an alcohol drinking contest in Henan province were also ordered to pay a compensation of over US$70,000 after one participant died due to excessive alcohol intake in July of 2017.

These cases also triggered online discussions about how Chinese traditional drinking culture often encourages people at the table to drink as much as they can or to exceed their limits; the goal sometimes is to literally “take someone to the ground by drinking.” When someone proposes a toast, everyone at the table is required to finish their glasses, sometimes at a very high pace.

In light of the latest news, some commenters write on Weibo: “No matter what kind of drinking gathering it is, for someone who is already drunk, others should intervene to prevent them from continuing to drink. Even if they invite, provoke, or insist on drinking themselves, they should not be allowed to continue. Otherwise, it not only harms them, you might end up facing legal responsibility yourself.”

Others remind people that overindulging in alcohol when you’re in a state of distress is never a good idea, and that no heartbreak is worth getting drunk over: “There are plenty of other fish in the sea.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Health & Science

‘Sister Blood Points’ Controversy: Shanghai Woman’s Tibet Blood Donations Ignite Privilege Debate

Dozens of local public officials in Tibet donated blood to rescue a Shanghainese woman. Netizens believe it’s a matter of privilege.

Published

8 months agoon

December 9, 2023

The medical rescue of a critically injured Shanghai woman in Tibet has recently triggered major controversy on Chinese social media after netizens suspected that the woman’s treatment may have been facilitated through the abuse of power.

What was supposed to be a romantic honeymoon getaway turned into a nightmare for newlyweds Yu Yanyan (27, 余言言) and her husband Tao Li (29, 陶立).

On October 14, just two weeks after their wedding, the couple from Shanghai was driving on China’s National Highway 219. Their destination was Ngari Prefecture in Tibet’s far west, where the average elevation is 4500 meters.

As they drove by the famous mountain pass Jieshan Daban (界山達阪), situated at an altitude of 5347 meters, they suddenly realized that the altitude was affecting them. Soon, Tao Li, who was driving the car, lost consciousness and crashed the car. Yu Yanyan, on the passenger side, was badly injured in the crash.

The crashed car, image via Beijing News/Xinjinbao (source).

What followed was a complicated, time-sensitive, and costly rescue operation. At the Ngari People’s Hospital (阿里地区人民医院), Yu was diagnosed with a ruptured liver, abdominal bleeding, hemorrhagic shock, and thoracic trauma. She was losing a lot of blood in a short time and required surgery, but there was not enough blood available for a blood transfusion at the time in the sparsely populated region, as reported by Beijing News.

Tibetan Civil Servants to the Rescue

While the hospital made efforts to secure donations, specifically requiring an adequate supply of A+ type blood, Yu’s husband was reportedly advised to reach out to the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (上海卫健委) to inquire about potential assistance. One of his aunts, or his ‘auntie’, allegedly helped him to contact them.

These efforts appeared to be fruitful. Between October 16-17, just days following the crash, numerous members of the public and dozens of local civil servants in Tibet, including firefighters, policemen, and military personnel, stepped forward to donate blood, contributing to over 7000 mL of A-type Rh-positive blood that ultimately saved Yu’s life.

Allegedly thanks to the Tibet office of the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government, a medical specialist from Shanghai was even sent to assist in the medical treatment of Yu at the Ngari hospital.

As Yu later required more advanced medical care and surgeries, she was advised to go to a bigger hospital. She was then transferred via a specially arranged chartered plane. The total costs of this medical chartered plane flight from Ngari to Sichuan’s Huaxi hospital (四川华西医院), arranged by Yu’s father, allegedly cost 1,2 million yuan (US$169.230).

After receiving surgery at the Huaxi Hospital, Yu was in stable condition and was transferred to Shanghai.

An Abuse of Power?

Yu’s story began drawing notice, eventually garnering nationwide media coverage, after Yu herself posted a video on her social media account (Douyin) in which she recounted her experiences. Yu, who only had a relatively small group of followers, told about her rescue operation and her recovery. But instead of garnering sympathy, it led to many questions from netizens and went viral. The video was later deleted.

Screenshots from the since deleted Douyin video.

Who was the ‘auntie’ who reached out to the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission? How were Tibet public officials made to donate blood for this Shanghai patient? What power dynamics were in play that facilitated the mobilization of people in this manner by the family?

People became upset, as they suspected Yu’s life had only been saved because of an abuse of power, and that ordinary Chinese patients would never have never received a similar treatment.

They started referring to Yu as ‘Sister Blood Points.’ The Chinese term is xuè cáo jiě 血槽姐, with xuè cáo 血槽 (lit. blood groove) often being used in the world of gaming to refer to the health bar, an image in video games that shows the player how much energy or blood or strength they have left before it’s game over.

Various online AI-generated images featuring a portrayal of “Sister Blood Points.”

There were also various digital (AI-generated) images showing Yu surrounded by bags of donated blood, portraying her as a privileged, blood-sucking Shanghai ‘princess’ in Tibet.

Following the online commotion, the Ngari Propaganda Department issued a statement on November 29 promising to look into the issue. Additionally, in the first week of December, various Chinese media outlets also started to investigate the case.

An Ordinary Patient in Extraordinary Circumstances

On December 6, online newspaper The Paper (澎湃新闻) published an article together with Shangguan News (上观新闻) which answered some of the most pressing questions surrounding the case.

The Paper reported that they found no officially organized mobilization of public officials or members of the public to donate blood. Instead, local workers and individuals donated blood after learning about the woman’s situation through various channels, including from the hospital staff. Yu Yanyan’s husband Tao called the successful blood donation campaign a result of “multi-party mobilization” (“这是我们多方动员的结果,确实不是有组织的。”)

The Shanghai Municipal Health Commission also denied that they had contacted health authorities in Tibet to ask civil servants to donate blood. They claimed their members of staff did not personally know the patient nor any members of her or her husband’s family.

Furthermore, the article says that the woman known as ‘auntie’ is a 60-year-old retired woman who previously worked at a crafts factory. Upon learning about Yu’s predicament, she forwarded the information to her daughter-in-law, who works at a bank and also did all she could to spread the news and ask for help. This eventually led to the Tibet office of the Shanghai Municipal People’s Government being updated on the situation.

The Tibet office has refuted any suggestion that personal relationships influenced the procedures that resulted in the dispatch of a Shanghai medical expert to assist at Ngari People’s Hospital. A Shanghai medical team stationed in Tibet received a request for urgent support at the hospital and, following their ethical work guidelines, dispatched an expert to provide assistance.

The Paper further stated that nor Yu, nor her husband or their family were officials. In order to pay for the medical flight, Yu’s parents used family savings and borrowed money from others.

All of the information that was coming out about the entire ordeal seemed to indicate that Yu was just an ordinary patient in extraordinary circumstances.

A Sign of Distrust

While certain commenters believe that the latest information has put an end to weeks of speculation, others continue to harbor suspicions that there might be more to the story – they are not satisfied with the answers provided on December 6.

As some netizens dug up screenshots of online calls for help from Tao, Yu’s husband, some commenters responded: “This only makes it clearer that there’s no special status (特殊身份) here. Real influential officials wouldn’t go so low as to seek help online. A simple phone call would have quickly resolved their issue.”

In the end, the entire ordeal, now labeled “The Civil Servant Blood Donation Incident” (公务员献血事件) on Chinese social media, reveals more about public distrust in the transparency of China’s healthcare system than it does about Yu, her family, or the situation in Tibet.

While frustrations regarding privilege and power abuse within China’s healthcare system have existed for years, this issue has gained significant public attention this year in light of the launch of a top-down anti-corruption campaign targeting the healthcare industry.

This issue is especially important due to China’s longstanding struggle with public mistrust in the medical care sector. Some studies even suggest that China’s healthcare system has suffered from a “trust crisis among the public” since the 1990s (Chen & Cheng 2022, 2).

Multiple factors contribute to the relatively low trust in the Chinese healthcare system, but access and costs both play major roles. The sentence “Getting medical attention is difficult, getting medical attention is expensive” (Kànbìng nán, kànbìng guì 看病难,看病贵) has become a well-known expression among Chinese patients dissatisfied with the challenges they encounter in both accessibility and affordability when seeking medical treatments.

Most medical providers in China have become increasingly commercialized and profit-driven since the 1980s, leading to problems with crime and corruption within the medical system as medical professionals are expected to balance both a focus on patient well-being and financial gain. With doctors contending with low pay and incentive-based labor, bribery has emerged as a well-known problem, often considered somewhat of an “open secret” (Fun & Yao 2017, 30-31).

The prevalence of such issues has fueled public frustration, making individual cases like Yu Yanyan’s a source of intense controversy. In an environment where “getting medical attention is difficult, getting medical attention is expensive,” and where corruption is a notorious problem, many people simply do not think it is possible for one young woman to receive so much medical assistance from doctors and civil servants without the involvement of connections, power abuse, and bribery in the process.

Now that more details about the ‘blood point sister’ story have come to light, most netizens have started to question the truth behind this story and realize that Yu might just be an ordinary citizen, while some bloggers are still demanding more answers. In the end, most agree that it is not really about Miss Yu at all, but about whether or not they could expect similar medical treatment if they would end up in such a terrible situation.

“Is there currently an emergency response system in place that allows ordinary people to seek help in equally urgent crises?” (“当前是否存在一个紧急响应机制,可以让普通人在遇到同样紧急的危机时,能寻求帮助?”) one Sina blogger wonders.

“It is actually not important to know if they had special privileges or not,” one Weibo commenter writes: “I just hope that if patients need donated blood in the future, they will get the same treatment.”

By Manya Koetse, with contributions by Miranda Barnes

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

References:

Chen, Lu, and Miaoting Cheng. 2022. “Exploring Chinese Elderly’s Trust in the Healthcare System: Empirical Evidence from a Population-Based Survey in China.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (24): 16461-.

Fun, Yujing & Zelin Yao. 2017. “A State of Contradiction: Medical Corruption and Strain in Beijing Public Hospitals. In: Børge Bakken (Ed.), Crime and the Chinese Dream, Hong Kong University Press: 20–39.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?

edwin castelblanco

March 17, 2016 at 2:36 am

looking to start exporting powder milk to china , im in the USA any info would be a great help

steve baekelandt

December 21, 2016 at 12:55 pm

i can provide see link https://1drv.ms/f/s!ApnJpVjUl78thkJpj7GRuo4T-OKS all nestle nan

Oliver

April 24, 2019 at 12:59 pm

New update : 1child policy is stopped… and there is a new increase of demand for Western Baby formula Brand.

the top five infant formula firms in China are all based in the U.S. and Europe, accounting for 40 percent of the market.

max

May 4, 2019 at 4:29 am

It is a Brand Market you are right