PREMIUM NEWSLETTER | ISSUE #28

Dear Reader,

It’s been a little while since the last Weibo Watch newsletter. Those of you who follow me on X might already know that some personal circumstances have made it difficult for me to get a lot of work done this month following the unfortunate loss of two close family members and all the arrangements surrounding it. When it rains, it sometimes really does pour. However, life goes on, and I’m now ready to return to doing what I love most at What’s on Weibo. Thank you for your understanding as we dive back into the swing of things.

On that note, I am very happy to share some exciting news: my work at What’s on Weibo is the focus of a new study by Prof. Bai Liping (白立平) from the Department of Translation at Lingnan University (Hong Kong). The study, titled “Bloglator in the Era of Social Media: A Case Study of the Reports about the ‘Tragically Ugly’ Math Textbooks on What’s on Weibo,” has been published in Perspectives journal (2024, 1–16). You can find a link to the study here (limited free online copies available).

The study examines the role played by bloggers in the present-day news ecosystem, where social media has become increasingly important in various ways, making both news consumption and news production more multi-dimensional. In doing so, Bai zooms in on What’s on Weibo (WoW) as a prominent example of what he calls a ‘bloglator’: a blend of ‘blog’ and ‘translator’ to refer to someone who “translates, adapts, and recreates content from articles or posts on blogs, or does any translation on blogs” (3).

The research suggests that WoW’s work, reporting on trending topics on Chinese social media since 2013, constitutes a special form of news-related blog translation as well as blog-related news translation, carving out a special niche within journalistic translation and the broader news ecosystem.

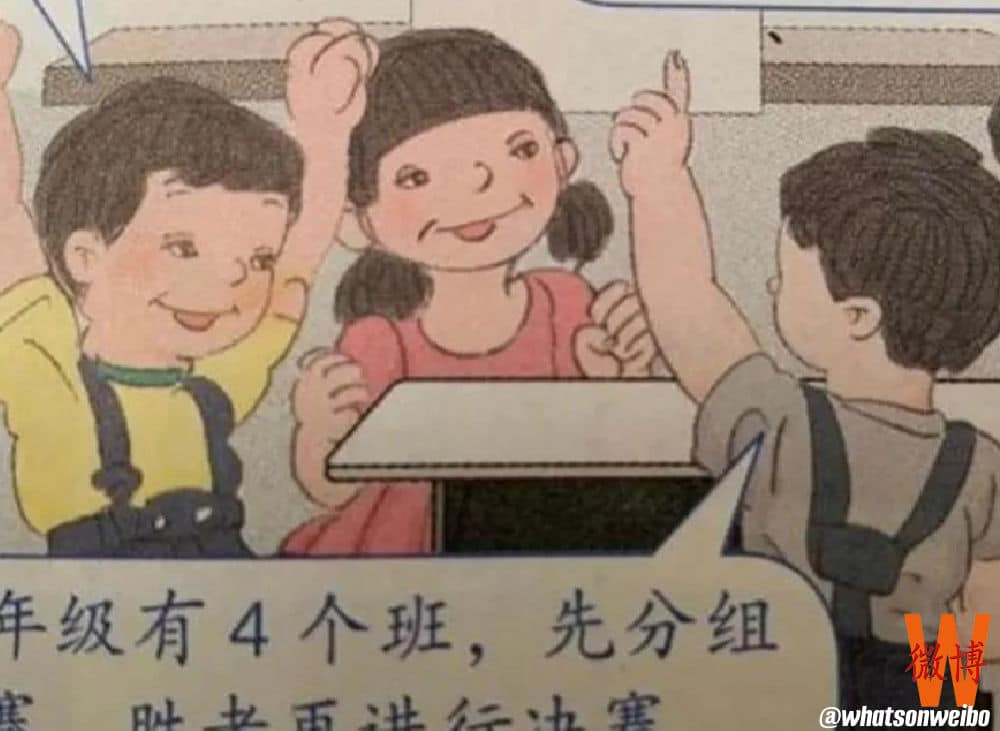

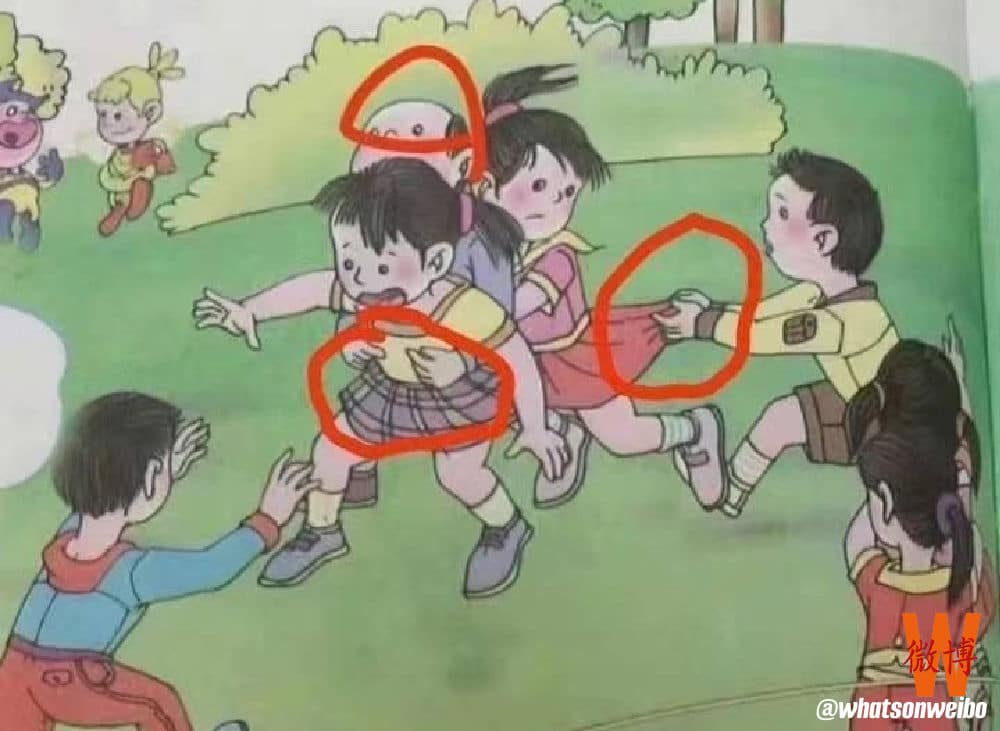

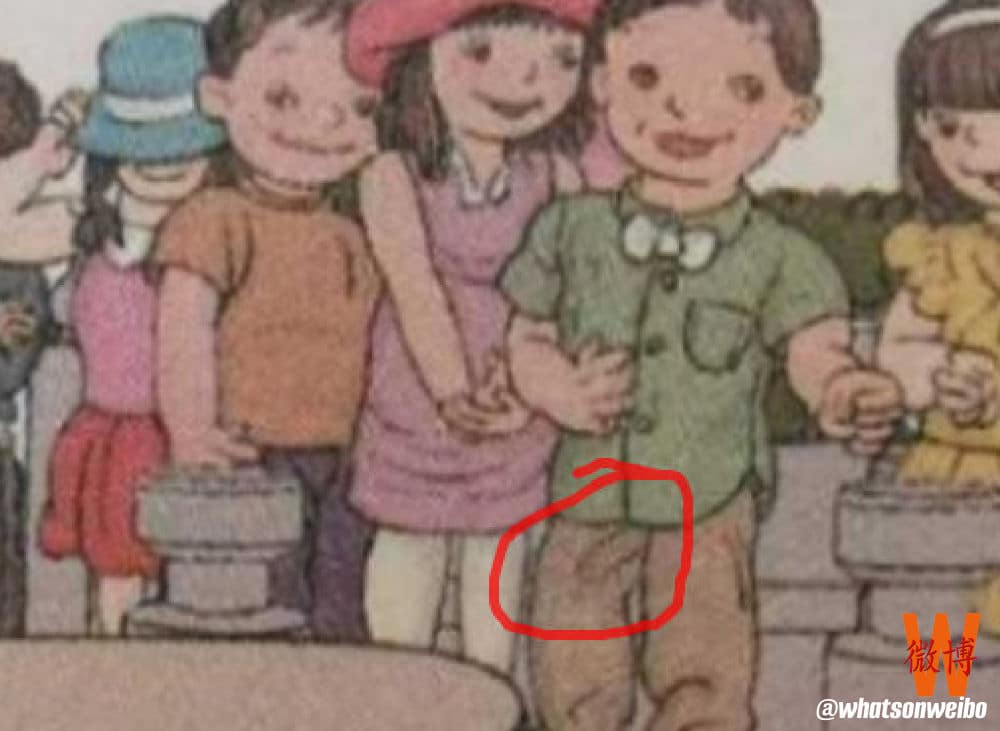

Serving as a case study is an article published on the site in May 2022 about illustrations in a Chinese schoolbook series for children that triggered controversy on Weibo for their peculiar design and for being perceived as ‘aesthetically displeasing.’

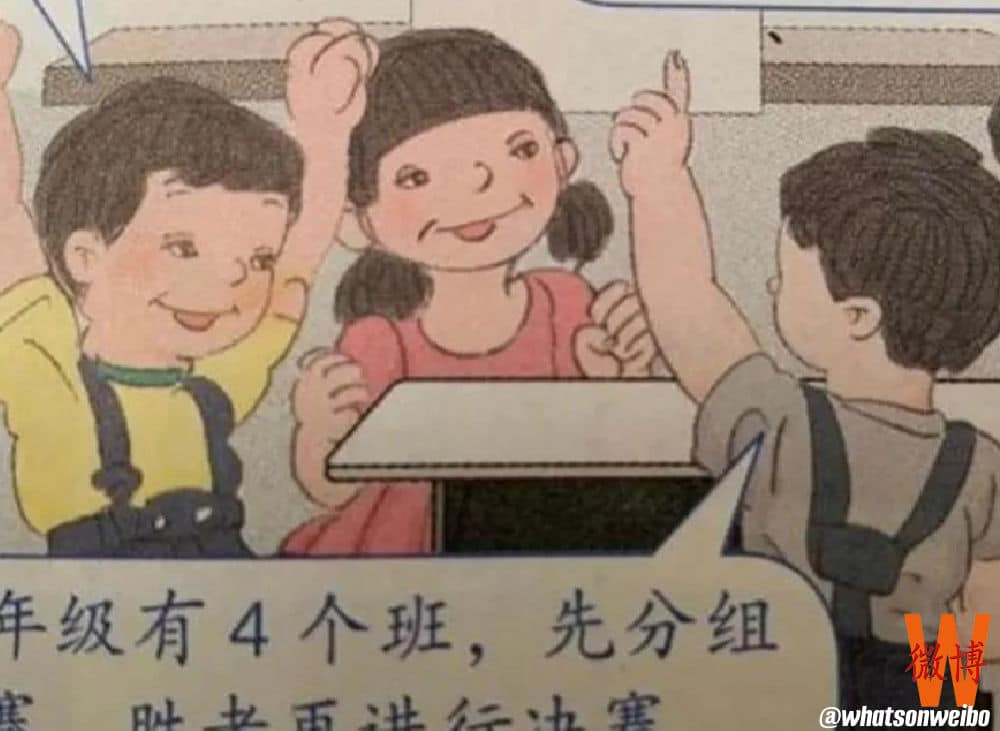

The controversy began when concerned parents noted that the quality of the design in their kids’ math textbooks was ugly, unrefined, and overall weird.

The controversial schoolbook.

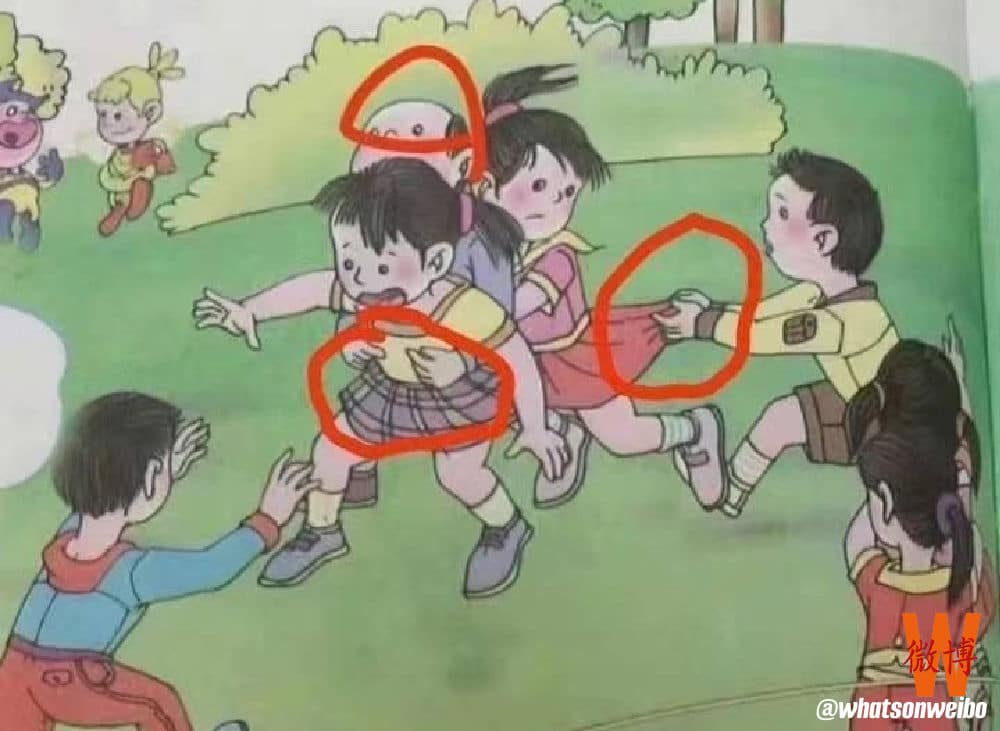

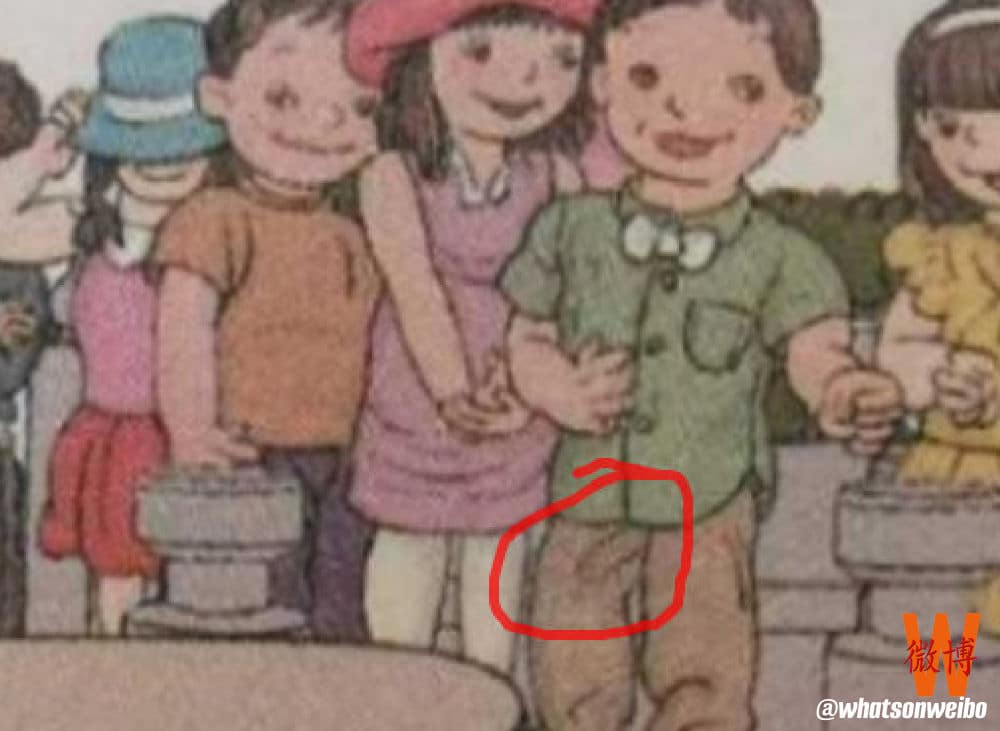

Children depicted in the math book illustrations had small, droopy eyes and big foreheads. Besides the poor design quality, many people found some illustrations inappropriate: a girl sticking out her tongue, recurring depictions of American flag colors, an incorrect depiction of the Chinese flag, a bulge in the pants of depicted boys, and boys grabbing girls. These elements led many to believe the books had “evil intentions,” with parents expressing concern that these “tragically ugly” books could negatively impact children’s aesthetic appreciation.

The explosive online discussions about the textbooks sparked a chain of events, covered in various articles here. Ultimately, it led to an official investigation by China’s Ministry of Education, holding 27 staff members accountable for their poor performance.

Among them were the Party Committee Secretary of the People’s Education Press, President Huang Qiang, who received a “serious warning” from the Party. Chief Editor Guo Ge was removed from office, along with others, including the head of the editorial office for elementary school mathematics textbooks. Illustrator Wu Yong and two other designers involved in the mathbooks reportedly will never work on national school textbooks or related projects again. The entire event was significant in various ways, also drawing increased attention to the quality of illustrations in teaching materials and shedding light on the dynamics behind Chinese schoolbook publications.

Bai’s study notes that WoW was among the first English websites to report on this topic, subsequently picked up by numerous other media outlets. While some sources, such as Australian news site news.com.au and The Guardian, included links or references to WoW, other news sites did not explicitly mention WoW but still used my translations, most notably the “tragically ugly” comment.

This non-literal translation of a Chinese phrase (most probably derived from 惨不忍睹 cǎn bù rěn dǔ “so horrible that one cannot bear to look at it”) exemplifies “translingual quoting,” a process where the original discourse is translated during quoting (6). You could consider it a ‘creative translation’ to convey meaning rather than exact words. As other reports also reproduced these exact words, it was evident what their source was. These two words ultimately became pivotal in the English coverage of the event; even today, a Google search directs you to this textbook controversy.

By examining the influence of the “tragically ugly” schoolbook case, Bai demonstrates that WoW reporting had considerable impact on the overall international media coverage of the event. It was cited by various English media outlets from Australia to the UK, from India to Hong Kong, including in traditional newspapers like The Independent, Sunday Times, and South China Morning Post.

He concludes:

“In the era of social media, just as Weibo has supplemented traditional media in the Chinese news ecosystem, WoW has filled a niche left by traditional media in the English news media ecosystem. Through WoW, readers can stay informed about the trending topics on Weibo, learn the views of the netizens and foster a deeper understanding of Chinese social and cultural life. The case study demonstrates that WoW’s reports about the tragically ugly math textbooks are consistent with its founder’s objectives of explaining the stories behind the hashtag and facilitating a better understanding of contemporary China, and that a ‘bloglator’ may play an important role in the evolving news ecosystem in this era of social media.”

Of course, I’m thrilled to see this finalized study on WoW’s impact in the news ecosystem. Beyond that, I value the term ‘bloglator,’ which aptly describes my role, and is different from the work done by journalists who translate news. It involves various strategies such as translingual quoting, providing explanations and background contexts, omitting irrelevant information, summarizing source texts, and most importantly, complete independence in choosing what to write about & the best way to cover it.

This independence enables WoW to spotlight interesting, noteworthy topics that help you stay connected to the Chinese social media sphere and its dynamics. As a subscriber, your support makes What’s on Weibo’s continuity possible. I look forward to working on many more topics in the future. Even the “tragically ugly” ones can sometimes turn out beautifully.

Best,

– Your ‘bloglator,’

Manya Koetse

(@manyapan)

References:

Bai, Liping. “Bloglator in the Era of Social Media: A Case Study of the Reports about the ‘Tragically Ugly’ Math Textbooks on What’s on Weibo.” Perspectives, (2024), 1–16. doi:10.1080/0907676X.2024.2343047.

What’s Been Trending

A closer look at some featured stories

1: “Fat Cat Jumping Into the River Incident” (胖猫跳江事件) | The tragic story behind the recent suicide of a 21-year-old Chinese gamer nicknamed ‘Fat Cat’ has become a major topic of discussion on Chinese social media, touching upon broader societal issues from unfair gender dynamics to businesses taking advantage of grieving internet users. We explain the trend here👇🏼

Read more

2: TV show Triggers Nationalistic Sentiments | Forget about previous song competitions. Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ is all the talk these days. Besides memes and jokes, the show – which now invited notable foreign talent to compete against Chinese established performers – has set off a new wave of national pride in China’s music and performers on Chinese social media.

Read more

3: Storm over a Smoky Cup of Tea | Chinese tea brand LELECHA faced backlash for using the iconic literary figure Lu Xun to promote their “Smoky Oolong” milk tea, sparking controversy over the exploitation of his legacy. “Such blatant commercialization of Lu Xun, is there no bottom limit anymore?”, one Weibo user wrote. Another person commented: “If Lu Xun were still alive and knew he had become a tool for capitalists to make money, he’d probably scold you.”

Read more

This is an on-site version of the Weibo Watch newsletter by What’s on Weibo. Missed the last edition of our newsletter? Find it here. If you are already subscribed to What’s on Weibo but are not yet receiving this newsletter in your inbox, please contact us directly to let us know.

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months ago

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months ago

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago