China History

“His Name Was Mao Anying”: Renewed Remembrance of Mao Zedong’s Son on Chinese Social Media

There has been a renewed focus on Mao Zedong’s son Mao Anying, who died on the North Korean War battlefield at the age of 28.

Published

2 years agoon

THIS IS A PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

Hundreds of Chinese state media and government channels posted a tribute to Mao Zedong’s oldest son on social media this week, commemorating the anniversary of his 100th birthday. The widespread publicity campaign shows a broader renewed focus on Mao Anying in Chinese online media, where official voices communicate why – and in which way – Mao Anying needs to be remembered by the Chinese people.

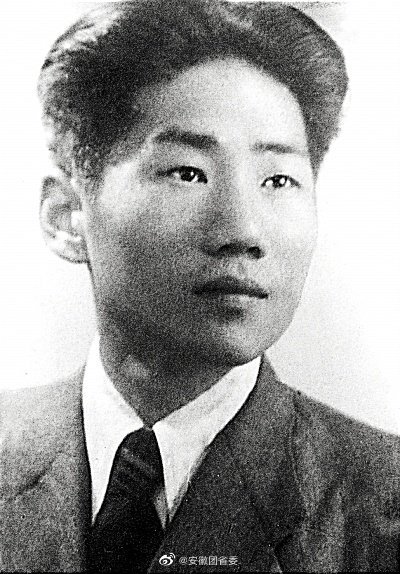

72 years after his death, Mao Anying is trending on Weibo. “Remembering Comrade Mao Anying’s 100th Birthday” became a popular hashtag on Weibo on October 24. Various official Chinese channels, including Global Times and the Communist Youth League, promoted the hashtag in their posts and included videos showing old footage featuring Mao Anying (毛岸英, 1922-1950), the first-born son of Mao Zedong and his second wife, Yang Kaihui.

“Let’s remember! In 1950 on November 25, at just 28 years old, Mao Anying sacrificed his life on the North Korean battlefield, Peng Dehuai called him the number one soldier of the volunteer army,” the Communist Youth League wrote on Weibo.

There has been a renewed focus on Mao Zedong’s son Mao Anying, who died on the Korean War battlefield at the age of 28 in 1950. A widespread online publicity campaign went trending this week, communicating why & how Mao Anying should be remembered. Read: https://t.co/rlRf2YxZWT pic.twitter.com/6SXTJbqc6M

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) October 27, 2022

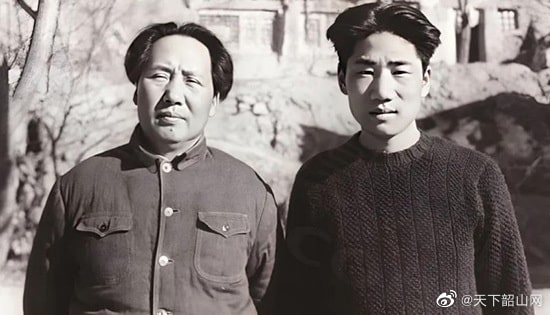

During the Korean War, the Chinese government, led by Mao Zedong, sent troops to fight in the war, and Mao’s son Mao Anying joined the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army.

It is said that Chinese military leader Peng Dehuai did not want Mao Anying to join, thinking it was far too dangerous for him, but Mao allegedly disagreed: “Who will go if my son doesn’t?” (Davin, Ch. 4).

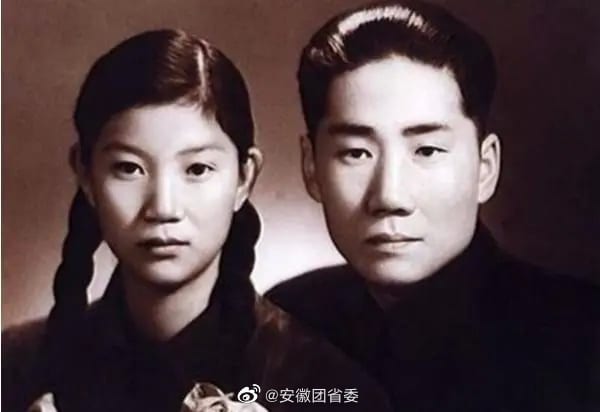

Mao Anying was killed in action by an American air strike a month after the start of this three-year war against US aggression in support of North Korea. He left behind his wife Liu Siqi (刘思齐), whom he had just married the year before his death.

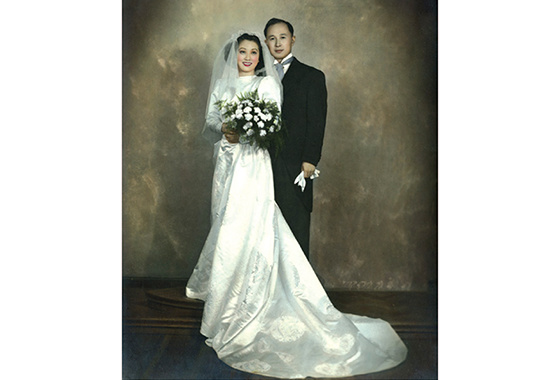

Mao Anying with his wife Liu Siqi, who passed away in January of 2022 at the age of 92. #刘思齐同志逝世##毛岸英妻子刘思齐逝世#

Mao Anying’s short life was definitely not all roses. He was not in contact with his father for most of his younger years as Mao Zedong lost contact with his wife Yang Kaihui when little Anying was just around five years old.

Mao Anying had two brothers.* His younger brother Mao Anlong (毛岸龙, 1927-1931) died due to dysentery when he was still a toddler. A policeman badly beat his other brother Mao Anqing (毛岸青, 1924-2007) in the 1930s which is said to have contributed to him being diagnosed with schizophrenia later on in life.

In 1930, their mother was executed in Changsha by nationalist forces after allegedly refusing to denounce Mao and the Communist Party. After living on the streets in Shanghai for some years, Mao Anying and his brother Mao Anqing were located by the Party and sent to the Soviet Union to get an education (Davin 2013, Ch. 2).

Mao Anying became a Russian translator for Peng Dehuai during the Korean War and was placed at the Taeyudong headquarters in North Korea in the fall of 1950. As American bomb attacks started to come dangerously close to the headquarters, Mao Anying was made to go to a cave system that functioned as a bomb shelter but, for some reason, joined two others to a nearby hut the next day, which is where he was bombed.

After Mao Anying was killed, Mao Zedong allegedly said that “it was his misfortune to be Mao Zedong’s son” (Davin 2013, Ch. 4; Forbes 2010, 12).

In 1990, when staff was sorting through Mao Zedong’s belongings, they discovered that he had always kept a small collection of his son’s belongings with him: two neatly folded t-shirts, one pair of socks, a military cap, and a towel. This story was shared on social media by official channels on October 24 of 2021 (#毛泽东默默收藏多年的毛岸英遗物#).

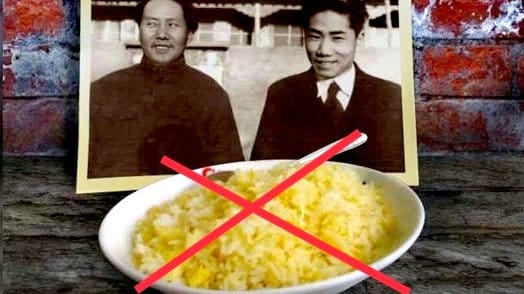

The Forbidden Egg Fried Rice Meme

One part of Mao Anying’s death that has become an ongoing, urban-legend-kind-of online story is that he supposedly disobeyed army rules and cooked egg fried rice at the Chinese headquarters. The smoke of the fire supposedly alerted the enemy and led to the bombing in which he would lose his life.

Although losing his favorite son – and his potential successor – was a tragedy to Mao Zedong, some Chinese are less remorseful about the young Mao never making it home, arguing that he could have continued Mao Zedong’s ruthless reign after his death.

The anniversary of Mao Anying’s death has therefore come to be celebrated by some netizens as “Egg Fried Rice Day” (蛋炒饭节) or “Chinese Thanksgiving” (中国感恩节), since it’s close to the American Thanksgiving. China Digital Times has a ‘digital space’ page dedicated to the online protest and meme in one, writing that eating egg fried rice is one the day’s ‘traditions.’

A few years ago, the sensitive nature of this meme became clear when a Chinese celebrity chef with many social media followers uploaded a video on October 25 on how to prepare Yangzhou-style fried rice. As described by Dennis E. Yi (2020), the chef was accused of “humiliating China” due to the alleged – and probably unintentional – connection to the Mao Anying rumors.

Chef Wang (美食作家王刚) made fried rice on October 24, a sensitive dish for a sensitive day. Read more via The China Project.

In 2021, the social media account of a Jiangsu branch of China Unicom was shut down after it posted an egg fried rice recipe on October 24.

In the same year, China’s Cyberspace released an official list including “rumors and fake information” related to the history of the Communist Party of China, including “key facts on revolutionary leaders, heroes and historical events.”

This list was compiled and published in order to “establish a correct view of the history of the Party and oppose historical nihilism” (Global Times 2021). The claim that Mao Anying died because he exposed himself while he was preparing fried rice with eggs was included on this list and was officially declared a rumor.

When the Korean war-themed movie The Battle at Lake Changjin became a major hit in fall of 2021, one Weibo user wrote that “fried rice was the best thing to come out of the whole Korean War,” after which they were jailed for ten days for “impeaching the reputation of heroes and martyrs.”

“Why Do We Remember Mao Anying?”

The recent widespread state media campaign surrounding Mao Anying’s birthday is noteworthy. One Weibo post by Changjiang Daily (长江日报) says:

“He is Mao Zedong’s son, he is the first soldier of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army, and he sacrificed his life with honor and glory on the North Korean battlefield. He is like his father and put his own flesh and blood into revolutionary work. His name was Mao Anying. Today, let us commemorate our comrade Mao Anying together.”

The same wording was also used in posts by other official channels, including by the Chinese police force, Wuhan City, Guangdong City, Ningxia, Nanchong Public Security, and many, many others.

State media outlet People’s Daily promoted the hashtag “Mao Anying Was the First Volunteer Soldier of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army” (#毛岸英是中国人民志愿军第一个志愿兵#), with other hashtags surrounding the commemoration of his birthday also circulating on Chinese social media, including “Why Do We Remember Mao Anying” (#我们为何纪念毛岸英#) and “Commemorating the 100th Birthday of Mao Anying” (#纪念毛岸英同志诞辰百年#).

The commemoration of Mao Anying’s 100th birthday went trending right after the ending of the 20th Party Congress and comes at a time when there is a renewed focus on remembering the Korean War (1950-1953).

The Korean War, referred to as ‘the War to Resist America and Aid Korea’ (抗美援朝战争), has become an important and recurring theme in multiple Chinese film productions, series, museums, and political events in recent years.

The 2020 movie The Sacrifice (金刚川), starring ‘Wolf Warrior’ actor Wu Jing, depicts the Korean War from different perspectives and focuses on the heroic role of ordinary soldiers. An exhibition at the Chinese Military Museum about the “glorious course and great achievements of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army” opened in 2020 as part of the 70th anniversary of the start of the war. In 2021, the Cemetery for Martyrs of the Chinese People’s Volunteers held a burial ceremony for 109 Chinese soldiers whose remains were returned by South Korea after seven decades (Conrad 2020; GT 2021).

But what has made the most impact on Chinese audiences is the 2021 blockbuster film The Battle at Lake Changjin, which provides a Chinese perspective on the start of the Korean War and the lead-up and unfolding of the battle of Chosin Reservoir, a massive ground attack of the Chinese 9th Army Group against American forces. The Chinese attack at Chosin is remembered as a glorious victory and strategic success for turning around the war situation in Korea and leading to a withdrawal of most of the UN forces by late 1950.

The movie’s narrative and script recurringly underline why this particular historical event should not be forgotten by the Chinese people. In one of the film’s earlier scenes, Mao Zedong talks to military leader Peng Dehuai in the days leading up to China’s decision to send out troops to North Korea, saying:

“[Our] country is newly established and thousands of things are waiting to be done. If it’s for our current situation, I really don’t want to fight this war. But if it’s for the future, and the peaceful development of our country over a few decades or a century, we must fight this war. The foreigners look down on us. Pride can only be earned on the battlefield.”

It is a scene that is telling for the narrative the movie conveys about the Chosin battle and the war at large, during which the Chinese troops were severely underestimated by the well-equipped U.N. forces.

After the ‘Century of Humiliation,’ the time from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s during which China was attacked, weakened, and torn by foreign forces, the Korean War and Chosin battle showed that the military strength of the People’s Republic of China was a new force to be reckoned with. By showing this strength, China did not just save the North Korean regime but also defended its own borders and the nation’s prestige.

The determination and fighting spirit of the Chinese soldiers at Chosin as depicted in the movie – one impressive scene shows dozens of soldiers frozen into “ice sculptures” while still in battle posture – struck a chord with Chinese audiences.

As part of this ‘re-remembrance’ of the Korean War in China, Mao Anying has been placed more prominently in the media spotlight.

The award-winning Battle at Lake Changjing also includes a scene showing how Mao Anying expresses his wish to join the army. After Peng Dehuai shares his disagreement, Mao Zedong comes out and says: “Let him go.” (You can watch the scene including English subtitles here.)

Mao Anying in the Battle at Lake Chanjin, played by actor Huang Xuan.

Although there already was a Chinese 34-episode TV drama dedicated to Mao Anying in 2010, the same year in which a statue of him was revealed by the North Korean border, the series focused more on the “special bond between father and son” and Mao Anying’s marriage to Liu Siqi, as the script was also partly based on Liu’s memoirs (Beijing Entertainment News 2010; CNR 2010).

It was not until more recently that Mao Anying’s legacy was officially and explictly contextualized within the frame of the victorious Korean War, specifically emphasizing the sacrifice Mao Anying made for his country.

In 2020 and in 2021, official Chinese channels began to actively promote stories about Mao Anying and his legacy on social media. The Chinese Historical Research Institute published the hashtag “The 70th Anniversary of Mao Anying Sacrificing His Life” (#毛岸英牺牲70周年#) in 2020, the same year when Chinese media featured posts about the ‘egg fried rice’ stories being “pure fabrications” and the need to “restore historical truth about the sacrifice of the martyr Mao Anying,”

No more egg fried rice rumors surrounding Mao Anying’s legacy – image posted by Guanchazhe on Weibo in 2020.

People’s Daily, for example, launched the hashtag “Mao Anying Was Only 28 Years Old When He Sacrificed His Life” (#毛岸英牺牲时年仅28岁#) in 2021. In the same year, Communist Youth League promoted the hashtag “71 Years Since Mao Anying Sacrificed His Life” (#毛岸英牺牲71周年#) and that the hashtag “Martyr Mao Anying Sacrificed His Life 71 Years Ago” (#毛岸英烈士牺牲71周年#) was launched, along with the slogan “Mao Anying Was the First Soldier of the Chinese Volunteer Army” (#毛岸英是志愿军第一名战士#).

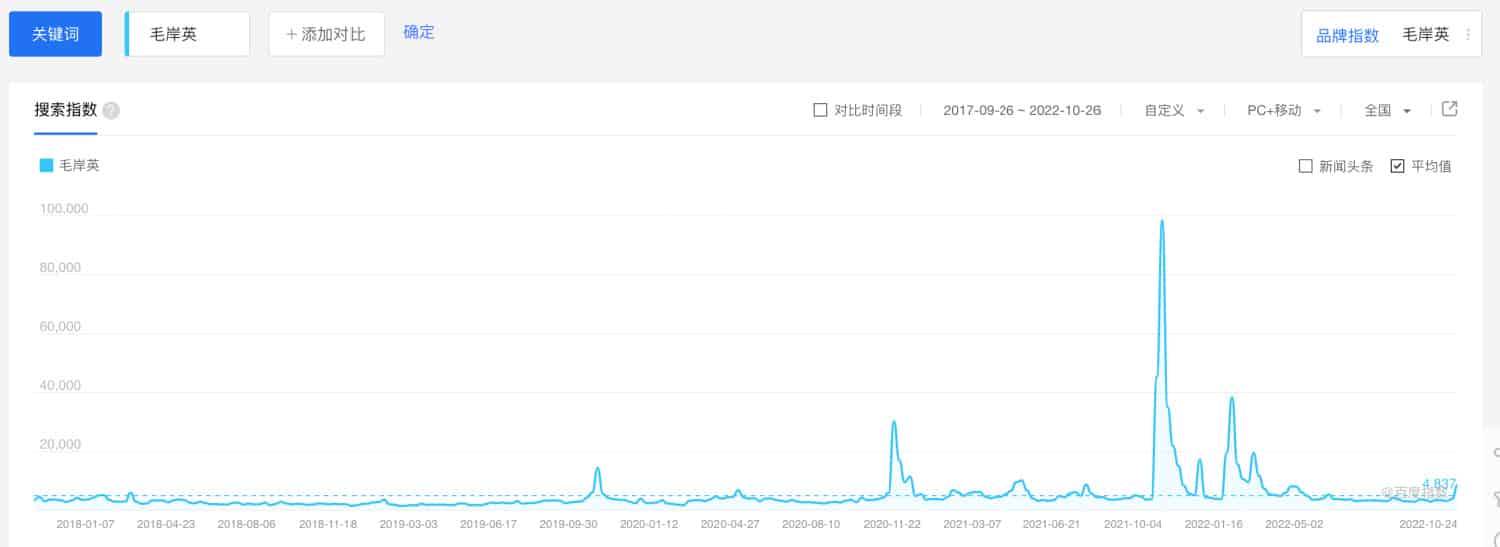

The increased interest in Mao Anying is also visible when looking up search query trends in the Chinese search engine Baidu via their Baidu Index tool. Over the past five years, there has been a gradual increase in people searching for the keyword ‘Mao Anying,’ with the absolute peak in popularity of the search engine coinciding with the release of the Battle at Lake Changjin film.

Screenshot of Baidu trend report, showing the frequence of search quary ‘Mao Anying’ on search engine Baidu from late October 2017 to late October 2022.

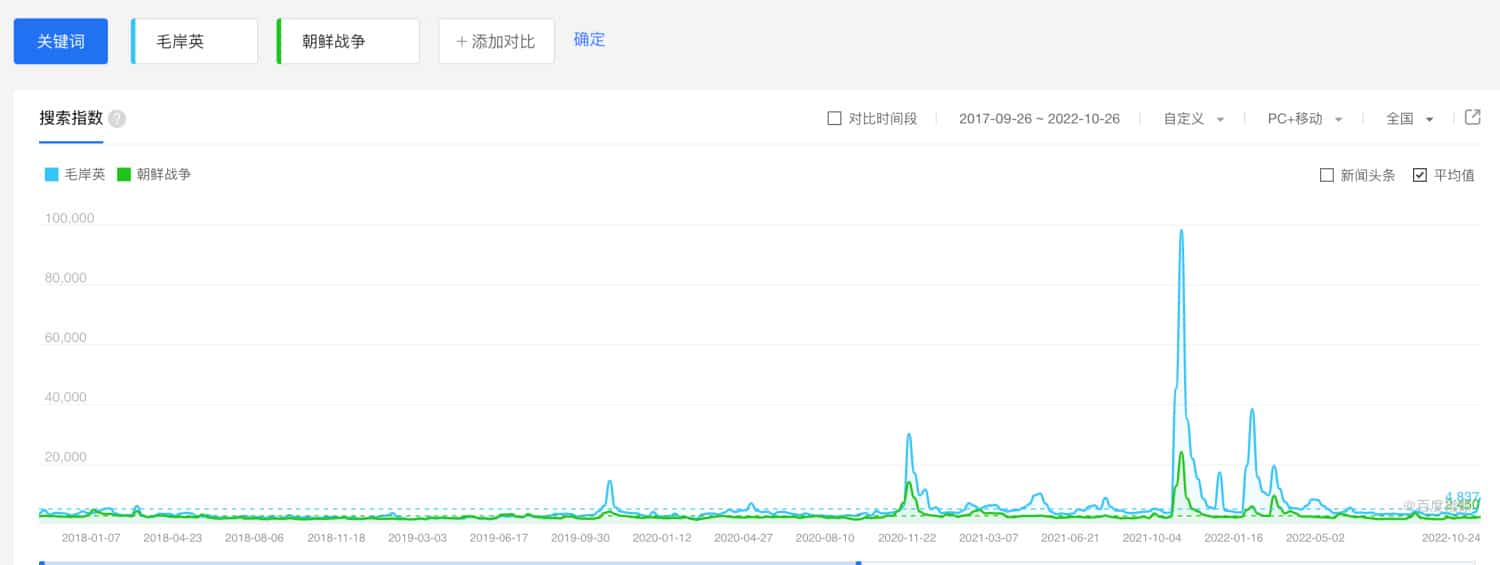

Baidu Index shows there is a correlation between the increased interest in the Korean War and the interest in Mao Anying.

The Baidu search engine tool also shows how there is a correlation between the terms ‘Korean War’ and ‘Mao Anying’, as they both see peaks in popularity at the same time (blue line is Mao, green line is Korean War).

Remembering Mao Anying, The Right Way at the Right Time

In remembering Mao Anying and incorporating his legacy into China’s collective memory in the context of the Korean War, several dynamics come together at the same time.

The ‘War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea’ or China’s overall participation in the Korean War is described as a “great victory” in fighting against the U.S. forces and as a “sound foundation” for China’s development as a newly established country “at a time when it was rather backward and in dire need of a full-scale reconstruction.” As state media outlet Global Times (2021) writes:

“This success ensured a peaceful development environment for China and secured the international prestige of the Chinese military through the war. The spirit of all young men and women who sacrificed for the country during the war was inherited.”

This specific kind of remembrance, in which Mao Anying plays a special role as “the first soldier to sacrifice his life,” comes at a time when Party ideology is strong, and is especially emphasized in the 2020-2022 period during important events such as the 70th anniversary of start of the Korean War, the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party of China, and the 20th Party Congress.

In Xi Jinping’s thoughts on China’s New Era and the journey towards a rejuvenated nation, you see a more assertive China and more focus on the country’s military strength and Party ideology (also see here and here).

Within this context, Mao Anying’s sacrifice for China’s future during the Korean War is more important than even before, especially in light of escalating political tensions between the U.S. and China, accompanied by a rise of Chinese nationalism.

It is therefore perhaps no coincidence that all the aforementioned things, from the launch of the Battle at Lake Changjin film, to the new remembering of Mao Anying on social media and the official listing of Mao Anying-related rumors as fabrications, took place within the last two to three years.

It is the ‘right’ time to commemmorate Mao Anying for the ‘right’ reasons: not just because he was Mao Zedong’s son or Liu Siqi’s husband, but because he was a Party leader’s son who joined the Chinese Volunteer Army and dedicated his life to “defending the country, serving the people, and strengthening the army” (China Military Online 2021).

“I salute you, hero,” one recurring popular comment on Weibo says. “Remember every hero who worked for the happiness of people in a New China!”

“He was a hero of the people,” others write: “You will never be forgotten.”

If you appreciate the work we do, please subscribe to What’s on Weibo to support us

By Manya Koetse

* Besides having three sons with his second wife Yang Kaihui, Mao Zedong would go on to have three daughters and three sons with He Zizhen, of which most either died young or were separated from their parents, and one daughter with his fourth wife Jiang Qing.

References (other primary sources included in text through hyperlinks)

Beijing Entertainment News 北京娱乐信报. 2010. “TV Series “Mao Anying” comes to CCTV, focusing on the love between father and son [电视剧《毛岸英》登陆央视 聚焦父子情]” (In Chinese). 北京娱乐信报, October 18 https://yule.sohu.com/20101018/n275860939.shtml [Oct 27, 2022].

China Military Online. 2021. “Mao Anying, forging ahead courageously and against all odds.” China Military, June 29 http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/2021special/2021-06/29/content_10056685.htm [Oct 27, 2022].

CNR (China National Radio) 中广网. 2010. “Liu Siqiu: The TV Series ‘Mao Anying’ Is My Gift to Him [刘思齐:电视剧《毛岸英》是我送岸英的礼物]” (In Chinese). 中广网, October 21 http://www.taiwan.cn/plzhx/zht/201010/t20101021_1569029.htm [Oct 27, 2022].

Conrad, Jennifer. 2020. “70 years on, how China sees the Korean War.” The China Project, Oct 14 https://thechinaproject.com/2020/10/14/70-years-on-how-china-sees-the-korean-war/ [Oct 27, 2022].

Davin, Delia. 2013. Mao: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Purchase here).

Forbes, Cameron. 2010. The Korean War – Australia in the Giants’ Playground. Sydney: MacMillan.

Global Times. 2021. “Sacrifices from CPC’s young heroes, past and present, continue to inspire new generations.” Global Times, July 8 https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202107/1228123.shtml [Oct 27, 2022].

Global Times. 2021. “China releases list of rumors on Party history, martyrs to fight historical nihilism.” Global Times, July 16 https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202107/1228819.shtml [Oct 27, 2022].

Global Times. 2021. “Remains of 109 Chinese People’s Volunteers soldiers return from South Korea to China.” Global Times, Sep 2 https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202109/1233202.shtml [Oct 27, 2022].

Yi, Dennis E. 2020. “Fried rice backlash: Why Chinese internet users turned on a celebrity chef.” The China Project, November 11 https://thechinaproject.com/2020/11/11/fried-rice-backlash-why-chinese-internet-users-turned-on-a-celebrity-chef/ [Oct 27, 2022].

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2022 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China History

A Chinese Christmas Message: It’s Not Santa Bringing Peace, but the People’s Liberation Army

On social media, Chinese official channels are not celebrating a Merry Christmas but instead focus on a Military Christmas.

Published

7 months agoon

December 26, 2023

It is not Santa bringing you peace and joy, it is the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Chinese state media and other influential social media accounts have been pushing an alternative Christmas narrative this year, which makes it very clear that this ‘Merry Christmas’ is brought by China’s military forces, not by a Western legendary figure.

On December 24, Party newspaper People’s Daily published a video on Weibo featuring various young PLA soldiers, writing:

“Thank you for your hard work! Thanks to their protection, we have a peaceful Christmas Eve. They come from all over the country, steadfastly guarding the front lines day and night. “With our youth, we defend our prosperous China!” Thank you, and salute!”

People’s Daily post on Weibo, December 24 2023.

The main argument that is propagated, is that this time in China should not be about Christmas and Santa Claus, but about remembering the end of the Korean War and paying tribute to China’s soldiers.

This narrative is not just promoted on social media by Chinese official media channels, it is also propagated in various other ways.

One Weibo user shared a photo of a mall in Binzhou where big banners were hanging reminding people of the 73rd anniversary of the Battle of Chosin Reservoir during the Korean War: “December 24 is not about Christmas Eve, but about the victory at Chosin Reservoir.”

Mall banners reminding Chinese that December 24 is about commemorating the end of the Second Phase Offensive (photo taken at 滨州吾悦广场/posted by 武汉潘唯杰).

Another blogger posted a video showing LED signs on taxis, allegedly in the Hinggan League in Inner Mongolia, with the words: “December 24 is NOT Christmas Eve, it is the military victory of the Battle of Chosin Reservoir” (“12.24不是平安夜,是长津湖战役胜利日”).

Chinese taxis with a message: December 24 is NOT "Christmas Eve" but a day to commemorate the Chinese victory during the Second Phase Offensive of the Korean War in 1950. It's not a Merry Christmas but a military one. Video posted on Weibo, allegedly recorded in Inner Mongolia. pic.twitter.com/XZlRTinmXr

— Manya Koetse (@manyapan) December 26, 2023

One social media video showed a teacher at a middle school in Chongqing also emphasizing to her students that “it’s not Father Christmas who brings us a happy and peaceful life, but our young soldiers!”

In the context of the Korean War (1950-1953), December 24 marks the conclusion of the Second Phase Offensive (1950), which was launched by the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army against the United Nations Command forces–primarily U.S. and South Korean troops.

The Chinese divisions’ surprise attack countered the ‘Home-by-Christmas’ campaign. This name stemmed from the UN forces’ belief that they would soon prevail, end the conflict, and be home well in time to celebrate Christmas. Instead, they were forced into retreat and the Chinese reclaimed most of North Korea by December 24, 1950.

The Battle of the Chosin Reservoir, also known as the the Battle at Lake Changjin, is part of this history. The battle began on November 27 of 1950, five months after the start of the Korean War. The 2021 movie Changjin Lake (长津湖/The Battle at Lake Changjin) provides a Chinese perspective on the lead-up and unfolding of this massive ground attack of the Chinese 9th Army Group, in which thousands of soldiers died.

Especially in recent years and in light of the launch of the blockbuster movie, there is an increased focus on the Chinese attack at Chosin as a glorious victory and strategic success for turning around the war situation in Korea and defending its own borders, underscoring the military strength of the People’s Republic of China as a new force to be reckoned with (read more here).

This Chinese Christmas narrative of honoring the PLA coincides with a series of popular social media posts from bloggers facing criticism for celebrating Christmas in China.

One of them is Liu Xiaoguang (刘晓光 @_恶魔奶爸_, 1.7 million followers), who wrote on December 25:

“Some people are criticizing me for celebrating Christmas Eve, because, by celebrating a foreign festival, I would be unpatriotic and forgetful of our martyrs. What can I say, in our family Christmas must be a big deal, even if I don’t come home it must be celebrated, because my mom is a Christian, and she’s very devout (..) So you see, on one hand I should promote traditional Chinese virtues, and show filial piety, on the other hand I should be patriotic and not celebrate foreign festivals.”

Meanwhile, other popular bloggers stress the importance of remembering China’s military heroes during this time. Influential media blogger Zhang Xiaolei (@晓磊) posted: “It’s not Santa Claus who gives you peace, it’s the Chinese soldiers! #ChristmasEve” (“给你平安的不是圣诞老人,而是中国军人!🙏#平安夜#”). With his post, he added various pictures showing Chinese soldiers frozen in the snow as also depicted in the Battle at Lake Changjin movie.

Throughout the years, Christmas has become more popular in China, but as a predominantly atheist country with a small proportion of Christians, the festival is more about the commercial side of the holiday season including shopping and promotions, decorations, entertainment, etc.

Nevertheless, Christmas in China is generally perceived as “a foreign” or “Western” festival, and there have been consistent concerns that the festivities associated with Christmas clash with traditional Chinese culture.

In the past, these concerns have led to actual bans on Christmas celebrations. For instance, in 2017, officials in Hengyang were instructed not to partake in Christmas festivities and several universities throughout China have previously cautioned students against engaging in Christmas-related activities.

Chinese political and social commentator Hu Xijin (@胡锡进) also weighed in on the issue. In his December 24 social media column, the former Global Times editor-in-chief wrote that there is no problem with Christmas Eve and the Second Phase Offensive victory day both receiving attention on the same day. Even if the younger generations in China view Christmas more as a commercial event rather than a religious one, it’s understandable for businesses to capitalize on this period for additional revenue. He wrote:

“In this era of globalization, holiday cultures inevitably influence each other. The Chinese government does not actively promote the rise of “Western holidays” for its own reasons, but they also have no intention to “suppress foreign holidays.” Some Chinese celebrate “Western holidays” and it is their right to do, they should not face criticism for it.”

Although many Chinese netizens post different viewpoints on this year’s Christmas debate, there are some who just don’t understand what all the fuss is about. “December 24 can be both Christmas Eve, and it can be Victory Day. It’s not like we need to pick one over the other. We are free to choose whatever.”

By Manya Koetse

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Backgrounder

“Oppenheimer” in China: Highlighting the Story of Qian Xuesen

Qian Xuesen is a renowned Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s.

Published

10 months agoon

September 16, 2023By

Zilan Qian

They shared the same campus, lived in the same era, and both played pivotal roles in shaping modern history while navigating the intricate interplay between science and politics. With the release of the “Oppenheimer” movie in China, the renowned Chinese scientist Qian Xuesen is being compared to the American J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In late August, the highly anticipated U.S. movie Oppenheimer finally premiered in China, shedding light on the life of the famous American theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967).

Besides igniting discussions about the life of this prominent scientist, the film has also reignited domestic media and public interest in Chinese scientists connected to Oppenheimer and nuclear physics.

There is one Chinese scientist whose life shares remarkable parallels with Oppenheimer’s. This is aerospace engineer and cyberneticist Qian Xuesen (钱学森, 1911-2009). Like Oppenheimer, he pursued his postgraduate studies overseas, taught at Caltech, and played a pivotal role during World War II for the US.

Qian Xuesen is so widely recognized in China that whenever I introduce myself there, I often clarify my last name by saying, “it’s the same Qian as Qian Xuesen’s,” to ensure that people get my name.

Some Chinese blogs recently compared the academic paths and scholarly contributions of the two scientists, while others highlighted the similarities in their political challenges, including the revocation of their security clearances.

The era of McCarthyism in the United States cast a shadow over Qian’s career, and, similar to Oppenheimer, he was branded as a “communist suspect.” Eventually, these political pressures forced him to return to China.

Although Qian’s return to China made his later life different from Oppenheimer’s, both scientists lived their lives navigating the complex dynamics between science and politics. Here, we provide a brief overview of the life and accomplishments of Qian Xuesen.

Departing: Going to America

Qian Xuesen (钱学森, also written as Hsue-Shen Tsien), often referred to as the “father of China’s missile and space program,” was born in Shanghai in 1911,1 a pivotal year marked by a historic revolution that brought an end to the imperial dynasty and gave rise to the Republic of China.

Much like Oppenheimer, who pursued further studies at Cambridge after completing his undergraduate education, Qian embarked on a journey to the United States following his bachelor’s studies at National Chiao Tung University (now Shanghai Jiao Tong University). He spent a year at Tsinghua University in preparation for his departure.

The year was 1935, during the eighth year of the Chinese Civil War and the fourth year of Japan’s invasion of China, setting the backdrop for his academic pursuits in a turbulent era.

Qian in his office at Caltech (image source).

One year after arriving in the U.S., Qian earned his master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Three years later, in 1939, the 27-year-old Qian Xuesen completed his PhD at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the very institution where Oppenheimer had been welcomed in 1927. In 1943, Qian solidified his position in academia as an associate professor at Caltech. While at Caltech, Qian helped found NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

When World War II began, while Oppenheimer was overseeing the Manhattan Project’s efforts to assist the U.S. in developing the atomic bomb, Qian actively supported the U.S. government. He served on the U.S. government’s Scientific Advisory Board and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel.

The first meeting of the US Department of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board in 1946. The predecessor, the Scientific Advisory Group, was founded in 1944 to evaluate the aeronautical programs and facilities of the Axis powers of World War II. Qian can be seen standing in the back, the second on the left (image source).

After the war, Qian went to teach at MIT and returned to Caltech as a full-time professor in 1949. During that same year, Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Just one year later, the newly-formed nation became involved in the Korean War, and China fought a bloody battle against the United States.

Red Scare: Being Labeled as a Communist

Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen both had an interest in Communism even prior to World War II, attending communist gatherings and showing sympathy towards the Communist cause.

Qian and Oppenheimer may have briefly met each other through their shared involvement in communist activities. During his time at Caltech, Qian secretly attended meetings with Frank Oppenheimer, the brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Monk 2013).

However, it was only after the war that their political leanings became a focal point for the FBI.

Just as the FBI accused Oppenheimer of being an agent of the Soviet Union, they quickly labeled Qian as a subversive communist, largely due to his Chinese heritage. While the government did not succeed in proving that Qian had communist ties with China during that period, they did ultimately succeed in portraying Qian as a communist affiliated with China a decade later.

During the transition from the 1940s to the 1950s, the Cold War was underway, and the anti-communist witch-hunts associated with the McCarthy era started to intensify (BBC 2020).

In 1950, the Korean War erupted, with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) joining North Korea in the conflict against South Korea, which received support from the United States. It was during this tumultuous period that the FBI officially accused Qian of communist sympathies in 1950, leading to the revocation of his security clearance despite objections from Qian’s colleagues. Four years later, in 1954, Robert Oppenheimer went through a similar process.

The 1950’s security hearing of Qian (second left). (Image source).

After losing his security clearance, Qian began to pack up, saying he wanted to visit his aging parents back home. Federal agents seized his luggage, which they claimed contained classified materials, and arrested him on suspicion of subversive activity. Although Qian denied any Communist leanings and rejected the accusation, he was detained by the government in California and spent the next five years under house arrest.

Five years later, in 1955, two years after the end of the Korean War, Qian was sent home to China as part of an apparent exchange for 11 American airmen who had been captured during the war. He told waiting reporters he “would never step foot in America again,” and he kept his promise (BBC 2020).

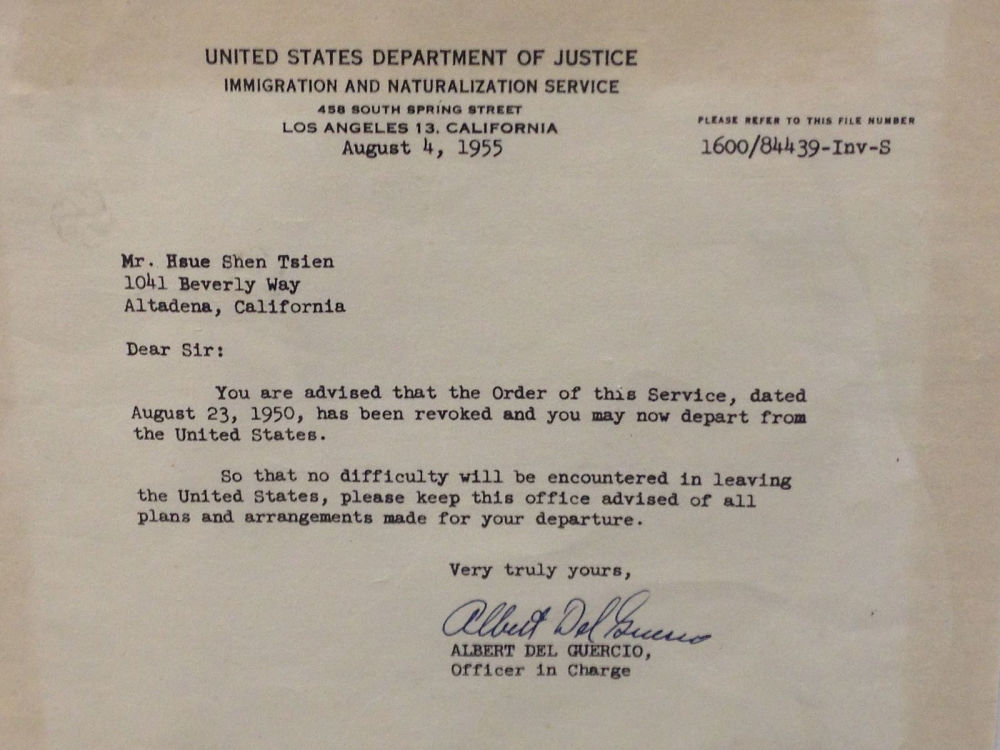

A letter from the US Immigration and Naturalization Service to Qian Xuesen, dated August 4, 1955, in which he was notified he was allowed to leave the US. The original copy is owned by Qian Xuesen Library of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where the photo was taken. (Caption and image via wiki).

Dan Kimball, who was the Secretary of the US Navy at the time, expressed his regret about Qian’s departure, reportedly stating, “I’d rather shoot him dead than let him leave America. Wherever he goes, he equals five divisions.” He also stated: “It was the stupidest thing this country ever did. He was no more a communist than I was, and we forced him to go” (Perrett & Bradley, 2008).

Kimball may have foreseen the unfolding events accurately. After his return to China, Qian did indeed assume a pivotal role in enhancing China’s military capabilities, possibly surpassing the potency of five divisions. The missile programme that Qian helped develop in China resulted in weapons which were then fired back on America, including during the 1991 Gulf War (BBC 2020).

Returning: Becoming a National Hero

The China that Qian Xuesen had left behind was an entirely different China than the one he returned to. China, although having relatively few experts in the field, was embracing new possibilities and technologies related to rocketry and space exploration.

Within less than a month of his arrival, Qian was welcomed by the then Vice Prime Minister Chen Yi, and just four months later, he had the honor of meeting Chairman Mao himself.

Qian and Mao (image source).

In China, Qian began a remarkably successful career in rocket science, with great support from the state. He not only assumed leadership but also earned the distinguished title of the “father” of the Chinese missile program, instrumental in equipping China with Dongfeng ballistic missiles, Silkworm anti-ship missiles, and Long March space rockets.

Additionally, his efforts laid the foundation for China’s contemporary surveillance system.

By now, Qian has become somewhat of a folk hero. His tale of returning to China despite being thwarted by the U.S. government has become like a legendary narrative in China: driven by unwavering patriotism, he willingly abandoned his overseas success, surmounted formidable challenges, and dedicated himself to his motherland.

Throughout his lifetime, Qian received numerous state medals in recognition of his work, establishing him as a nationally celebrated intellectual. From 1989 to 2001, the state-launched public movement “Learn from Qian Xuesen” was promoted throughout the country, and by 2001, when Qian turned 90, the national praise for him was on a similar level as that for Deng Xiaoping in the decade prior (Wang 2011).

Qian Xuesen remains a celebrated figure. On September 3rd of this year, a new “Qian Xuesen School” was established in Wenzhou, Zhejiang Province, becoming the sixth high school bearing the scientist’s name since the founding of the first one only a year ago.

In 2017, the play “Qian Xuesen” was performed at Qian’s alma mater, Shanghai Jiaotong University. (Image source.)

Qian Xuesen’s legacy extends well beyond educational institutions. His name frequently appears in the media, including online articles, books, and other publications. There is the Qian Xuesen Library and a museum in Shanghai, containing over 70,000 artefacts related to him. Qian’s life story has also been the inspiration for a theater production and a 2012 movie titled Hsue-Shen Tsien (钱学森).2

Unanswered Questions

As is often the case when people are turned into heroes, some part of the stories are left behind while others are highlighted. This holds true for both Robert Oppenheimer and Qian Xuesen.

The Communist Party of China hailed Qian as a folk hero, aligning with their vision of a strong, patriotic nation. Many Chinese narratives avoid the debate over whether Qian’s return was linked to problems and accusations in the U.S., rather than genuine loyalty to his homeland.

In contrast, some international media have depicted Qian as a “political opportunist” who returned to China due to disillusionment with the U.S., also highlighting his criticism of “revisionist” colleagues during the Cultural Revolution and his denunciation of the 1989 student demonstrations.

Unlike the image of a resolute loyalist favored by the Chinese public, Qian’s political ideology was, in fact, not consistently aligned, and there were instances where he may have prioritized opportunity over loyalty at different stages of his life.

Qian also did not necessarily aspire to be a “flawless hero.” Upon returning to China, he declined all offers to have his biography written for him and refrained from sharing personal information with the media. Consequently, very little is known about his personal life, leaving many questions about the motivations driving him, and his true political inclinations.

The marriage photo of Qian and Jiang. (Image source).

We do know that Qian’s wife, Jiang Ying (蒋英), had a remarkable background. She was of Chinese-Japanese mixed race and was the daughter of a prominent military strategist associated with Chiang Kai-shek. Jiang Ying was also an accomplished opera singer and later became a professor of music and opera at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing.

Just as with Qian, there remain numerous unanswered questions surrounding Oppenheimer, including the extent of his communist sympathies and whether these sympathies indirectly assisted the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Perhaps both scientists never imagined they would face these questions when they first decided to study physics. After all, they were scientists, not the heroes that some narratives portray them to be.

Also read:

■ Farewell to a Self-Taught Master: Remembering China’s Colorful, Bold, and Iconic Artist Huang Yongyu

■ “His Name Was Mao Anying”: Renewed Remembrance of Mao Zedong’s Son on Chinese Social Media

By Zilan Qian

Follow @whatsonweibo

1 Some sources claim that Qian was born in Hangzhou, while others say he was born in Shanghai with ancestral roots in Hangzhou.

2The Chinese character 钱 is typically romanized as “Qian” in Pinyin. However, “Tsien” is a romanization in Wu Chinese, which corresponds to the dialect spoken in the region where Qian Xuesen and his family have ancestral roots.

This article has been edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

References (other sources hyperlinked in text)

BBC. 2020. “Qian Xuesen: The man the US deported – who then helped China into space.” BBC.com, 27 October https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-54695598 [9.16.23].

Monk, Ray. 2013. Robert Oppenheimer: A Life inside the Center, First American Edition. New York: Doubleday.

Perrett, Bradley, and James R. Asker. 2008. “Person of the Year: Qian Xuesen.” Aviation Week and Space Technology 168 (1): 57-61.

Wang, Ning. 2011. “The Making of an Intellectual Hero: Chinese Narratives of Qian Xuesen.” The China Quarterly, 206, 352-371. doi:10.1017/S0305741011000300

Get the story behind the hashtag. Subscribe to What’s on Weibo here to receive our newsletter and get access to our latest articles:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2023 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?