China Digital

Hu Angang: Digital is Key in China’s 13th Five-Year Plan

China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) is underway. Renowned Chinese economics professor Hu Angang (胡鞍钢) talks about its main focuses, Chinese women consumers, and why digital is key for China’s future.

Published

8 years agoon

China’s 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) is underway. Renowned Chinese economics professor Hu Angang (胡鞍钢) talks about its main focuses, Chinese women consumers, and why digital is key for China’s future.

The 13th five-year plan is China’s latest policy blueprint for the 2016-2020 period. The influential state theorist and Dean of the School of Contemporary China at Tsinghua University (国情研究院) Professor Hu Angang (胡鞍钢) talks about the future plans of China as laid out in this blueprint during a special lecture in the National Library of China as part of the Visiting Programme for Young Sinologists (青年汉学家研修计划) [attended by author]. Digital innovation and developments play a major role in China’s future, according to Professor Hu. A special note: especially women play an important role in China’s (digital) growth.

China launched its first five-year plan (中国五年计划) in the 1953-57 period, aimed at rapid industrial growth. Its current 13th five-year plan is still fixed on growth, but with different characteristics. According to Professor Hu Angang, there are five different concepts within this period’s five-year plan, on which he also expanded in his recent 2016 work China’s New Theory: 5 Great Developments (中国新理念–五大发展).

The ‘big five’ include ‘innovation’, ‘harmonization’, ‘green’, ‘openness’, and ‘sharing’, Hu says – promoting more interaction between the government and the people, and between theory and concept.

DIFFERENT REVOLUTIONS

“In China, 1% of the population is equivalent to a middle-sized country – not even 1% can be left behind.”

According to Hu, the ‘big five’ development concepts are all about innovation-driven development – focused on people. The idea that ‘people are at the heart of the 13th five-year plan’ is something Hu also emphasized in earlier lectures this year.

China’s bold promise to end the country’s poverty by 2020 is one important part of the plan’s ‘people mission’ (“by the people, for the people, of the people” – as Hu puts it). The plan might be ambitious, but Hu is positive it will succeed: “China will lift all people out of poverty by 2020; 20 years ahead of the UN schedule.”

“How can we show that people are at the heart of the five-year plan?”, Professor Hu asks: “In western countries, they often talk about the majority ‘middle class’. But in China, just 1% of the population is equivalent to a middle-sized country. So our policies should cover and include all people – not even 1% can be left behind.”

Narrowing the rural-urban gap is part of the five-year plan mission, and as poverty-stricken rural areas often suffer from poor transportation, Hu states that improving the infrastructure of China’s more remote regions is a top priority. China already has the world’s longest HSR network with over 19,000 km, but this will have grown into a 50,000 km long HSR network by 2020.

Hu also mentions that high-speed metro rail systems will start operating between megacities, like the high-speed line that was opened in Shenzhen in late 2015. More subways, small-scale airports and long-distance large-capacity trams (as built in Jerusalem) are also part of the plan: “It will be a revolution of the transport system,” Hu says.

It is not the only revolution taking place in China in the coming few years according to Hu Angang – China’s digital revolution is in full force, and will go on for the years to come. Hu emphasizes that digital innovation development will also make an important contribution to ending poverty in China.

SMALL INVESTMENT, HIGH RETURNS

“In the digital age, the strongest countries are those that can master the digital space and manage digital users.”

Hu Angang tells that a recent visit to the mountainous southwestern province of Guizou, known for its rural villages, made him realize how tangible China’s rapid digital developments have become: “Residents used to live together with their pigs. Now they have local restaurants with fast wifi services. Those restaurant owners are very willing to provide these wifi services because it will attract more customers to come. For them, it is a small investment with a high return.”

That digital development has become increasingly important for China’s countryside is also visible through the rise of China’s so-called “Taobao villages” phenomenon – referring to rural villages that profit from local e-commerce businesses.

Because rural areas are now catching up with China’s digital developments, the ‘digital divide’ has become smaller. In 2015, China’s 688 million internet users formed the world’s largest online population. The 859 million mobile phone user group of 2010 has now increased to a staggering 1.3 billion, leading to a high digital penetration rate in the PRC.

These numbers are highly relevant according to Hu: “In the digital age, the strongest countries are those that can master digital space and manage digital users. As the country with the world’s most mobile phone and Internet users, China is now situated at the very center of the international digital era.”

China File recently reported that the state has already introduced a number of policies that specifically favor the development of rural e-markets, that is worth 460 billion RMB (±$70 billion US$) according to analysts – who predict that the next five years will be a “golden era” for rural e-commerce (China File 2016).

PUSHING IT TO THE NEXT LEVEL

“Innovation is the key word.”

In the next five years, Beijing wants to push China’s digital developments to the next level, further closing the urban-rural digital divide, boosting Chinese economy, and improving society efficiency. The promotion of China’s so-called ‘e-government’ is also part of this idea; making it possible for citizens to do much more online.

Last year, Alibaba’s Alipay and Sina Weibo launched a new ‘online city services platform’, where paying traffic fines, handling immigration issues or scheduling marriage registration no longer requires hourlong queuing at the Public Service Hall; instead, netizens can arrange it all from behind their mobile phones or computer screens: “E-government is already changing our lives,” Hu says – and according to him, we can expect China’s ‘e-government’ system to further develop in the coming five years – also suggesting that the ties between companies such as Alibaba, Tencent, Sina Weibo, and the government will deepen.

Professor Hu stresses that ‘innovation’ is the key word of the 13th five-year plan, which means that government spending on research and development will increase (“making China the second largest spender on R&D after the US”), and that the role of technology will also be strengthened through education.

THE FEMALE CONSUMER & ENTERPRENEUR

“Alibaba’s active buyers are totaled at 430 million – most of them being female consumers.”

Education is crucial to China’s further digital developments and (digital) economy in multiple ways, Hu explains, especially stressing the importance of promoting job opportunities, education and entrepreneurship for women.

Hu ties this subject to China’s flourishing e-commerce, mentioning the success of Alibaba, where active buyers are totaled at 430 million – most of them being female consumers. And in terms of sellers, it is also the women who have a major share: “So you can see if women are well-educated and actively employed, we can see the growth of an active new economic sector,” Hu says, connecting China’s female education and entrepreneurship to its booming e-commerce economy.

Emblematic of China’s e-commerce success is so-called “Single’s Day”, November 11, that has been marketed as a shopping spree day by Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba. Last November, Alibaba reported that its single’s day sales had skyrocketed to $14.3 billion.

Professor Hu mentions that creating more education and job opportunities for women is also relevant after they have given childbirth, stressing the importance of continuing education possibilities at different stages in life.

WORK IT OUT

“Each student should at least do one hour of exercise every day.”

The idea of investing in people at different stages throughout their life is a red line throughout Hu’s lecture, dividing it into the dimension of age and the dimension of capability: not only should people continue education at various levels throughout life, maintaining a lifestyle that contains health insurance and regular exercise is also key.

In the promotion of health-building programs, Hu refers to the focus on improving rural health proposed by Mao Zedong in the 1980s. The promotion of exercise is a low-cost measure to improve the overall health of citizens: “Just take a look at Beijing parks in the evenings and you will see that citizens are walking and exercising – this is an important idea for us. Each student should at least do one hour of exercise every day,” Hu says. China’s life expectancy currently is set at 75 years, an 1.5 year increase from previous years. In the new plan, it is expected to increase to 77.

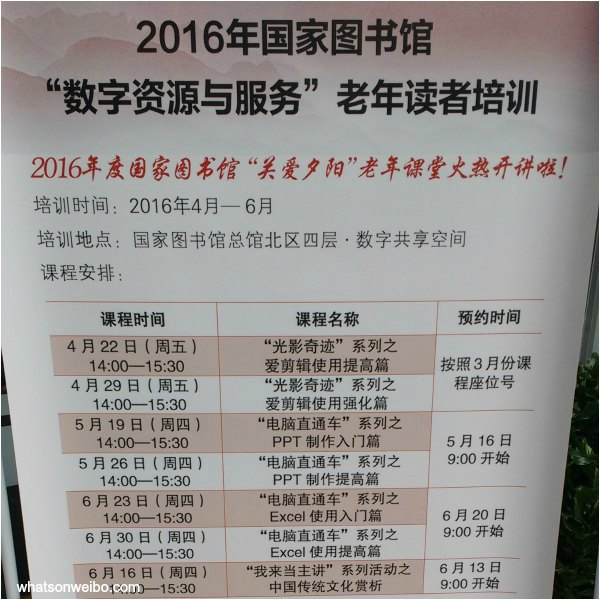

Libraries organize special classes for senior citizens, like this example from the National Library of China (Beijing) that teaches elderly how to work with Excel, amongst other topics.

In light of people’s continued learning, Hu mentions that more Chinese universities now provide post-college education for elderly people. In the weekends, many libraries and public cultural institutions provide courses aimed at senior citizens – the idea that learning does not stop after college is valued in China’s five-year plans.

TOO AMBITIOUS?

“In the past China used to be the country that copied products from other countries. In the future, China will be the inventor.”

Overall, Hu calls the 13th five-year plan a “blueprint of modernization”. By highlighting China’s technological and digital innovations, it does not just aim to benefit China’s economy and society – it also hopes to make China a nation of original inventions. Hu is confident: “In the past China used to be the country that copied products from other countries. In the future, China will be the inventor.”

According to the SIPO, China received 928,000 invention patent applications in the year 2014, accounting for 34% of the total global applications. Increasing public awareness about Intellectual Property was a focus issue in China’s previous five-year plan, and will remain to be one in this one. Earlier in 2016, the 16th nationwide publicity campaign of a “China Intellectual Property Week” helped draw public attention to IP.

With the revolution of China’s transport system and digital environment, and an increasing focus on green development, Hu foresees a reshaping of China’s economic landscape, which will also impact that of the world: “Is it too ambitious? No, it is not,” Hu states: “In the long run, China wants to contribute to bettering the world. It may not have contributed much over the past century – but it will in the next.”

– By Manya Koetse

Follow @WhatsOnWeibo

[rp4wp]

©2016 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

China Books & Literature

Why Chinese Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Shopping Festival

Bookworms love to get a good deal on books, but when the deals are too good, it can actually harm the publishing industry.

Published

2 months agoon

June 8, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

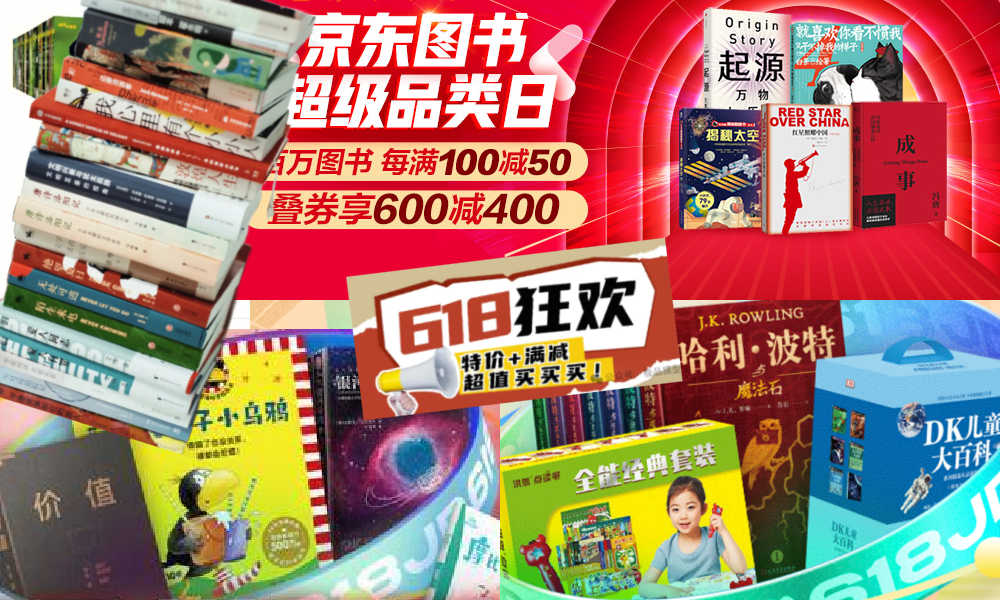

JD.com’s 618 shopping festival is driving down book prices to such an extent that it has prompted a boycott by Chinese publishers, who are concerned about the financial sustainability of their industry.

When June begins, promotional campaigns for China’s 618 Online Shopping Festival suddenly appear everywhere—it’s hard to ignore.

The 618 Festival is a product of China’s booming e-commerce culture. Taking place annually on June 18th, it is China’s largest mid-year shopping carnival. While Alibaba’s “Singles’ Day” shopping festival has been taking place on November 11th since 2009, the 618 Festival was launched by another Chinese e-commerce giant, JD.com (京东), to celebrate the company’s anniversary, boost its sales, and increase its brand value.

By now, other e-commerce platforms such as Taobao and Pinduoduo have joined the 618 Festival, and it has turned into another major nationwide shopping spree event.

For many book lovers in China, 618 has become the perfect opportunity to stock up on books. In previous years, e-commerce platforms like JD.com and Dangdang (当当) would roll out tempting offers during the festival, such as “300 RMB ($41) off for every 500 RMB ($69) spent” or “50 RMB ($7) off for every 100 RMB ($13.8) spent.”

Starting in May, about a month before 618, the largest bookworm community group on the Douban platform, nicknamed “Buying Like Landsliding, Reading Like Silk Spinning” (买书如山倒,看书如抽丝), would start buzzing with activity, discussing book sales, comparing shopping lists, or sharing views about different issues.

Social media users share lists of which books to buy during the 618 shopping festivities.

This year, however, the mood within the group was different. Many members posted that before the 618 season began, books from various publishers were suddenly taken down from e-commerce platforms, disappearing from their online shopping carts. This unusual occurrence sparked discussions among book lovers, with speculations arising about a potential conflict between Chinese publishers and e-commerce platforms.

A joint statement posted in May provided clarity. According to Chinese media outlet The Paper (@澎湃新闻), eight publishers in Beijing and the Shanghai Publishing and Distribution Association, which represent 46 publishing units in Shanghai, issued a statement indicating they refuse to participate in this year’s 618 promotional campaign as proposed by JD.com.

The collective industry boycott has a clear motivation: during JD’s 618 promotional campaign, which offers all books at steep discounts (e.g., 60-70% off) for eight days, publishers lose money on each book sold. Meanwhile, JD.com continues to profit by forcing publishers to sell books at significantly reduced prices (e.g., 80% off). For many publishers, it is simply not sustainable to sell books at 20% of the original price.

One person who has openly spoken out against JD.com’s practices is Shen Haobo (沈浩波), founder and CEO of Chinese book publisher Motie Group (磨铁集团). Shen shared a post on WeChat Moments on May 31st, stating that Motie has completely stopped shipping to JD.com as it opposes the company’s low-price promotions. Shen said it felt like JD.com is “repeatedly rubbing our faces into the ground.”

Nevertheless, many netizens expressed confusion over the situation. Under the hashtag topic “Multiple Publishers Are Boycotting the 618 Book Promotions” (#多家出版社抵制618图书大促#), people complained about the relatively high cost of physical books.

With a single legitimate copy often costing 50-60 RMB ($7-$8.3), and children’s books often costing much more, many Chinese readers can only afford to buy books during big sales. They question the justification for these rising prices, as books used to be much more affordable.

Book blogger TaoLangGe (@陶朗歌) argues that for ordinary readers in China, the removal of discounted books is not good news. As consumers, most people are not concerned with the “life and death of the publishing industry” and naturally prefer cheaper books.

However, industry insiders argue that a “price war” on books may not truly benefit buyers in the end, as it is actually driving up the prices as a forced response to the frequent discount promotions by e-commerce platforms.

China News (@中国新闻网) interviewed publisher San Shi (三石), who noted that people’s expectations of book prices can be easily influenced by promotional activities, leading to a subconscious belief that purchasing books at such low prices is normal. Publishers, therefore, feel compelled to reduce costs and adopt price competition to attract buyers. However, the space for cost reduction in paper and printing is limited.

Eventually, this pressure could affect the quality and layout of books, including their binding, design, and editing. In the long run, if a vicious cycle develops, it would be detrimental to the production and publication of high-quality books, ultimately disappointing book lovers who will struggle to find the books they want, in the format they prefer.

This debate temporarily resolved with JD.com’s compromise. According to The Paper, JD.com has started to abandon its previous strategy of offering extreme discounts across all book categories. Publishers now have a certain degree of autonomy, able to decide the types of books and discount rates for platform promotions.

While most previously delisted books have returned for sale, JD.com’s silence on their official social media channels leaves people worried about the future of China’s publishing industry in an era dominated by e-commerce platforms, especially at a time when online shops and livestreamers keep competing over who has the best book deals, hyping up promotional campaigns like ‘9.9 RMB ($1.4) per book with free shipping’ to ‘1 RMB ($0.15) books.’

This year’s developments surrounding the publishing industry and 618 has led to some discussions that have created more awareness among Chinese consumers about the true price of books. “I was planning to bulk buy books this year,” one commenter wrote: “But then I looked at my bookshelf and saw that some of last year’s books haven’t even been unwrapped yet.”

Another commenter wrote: “Although I’m just an ordinary reader, I still feel very sad about this situation. It’s reasonable to say that lower prices are good for readers, but what I see is an unfavorable outlook for publishers and the book market. If this continues, no one will want to work in this industry, and for readers who do not like e-books and only prefer physical books, this is definitely not a good thing at all!”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Digital

China’s 2024 Gaokao Triggers Online Discussions on AI

It’s Gaokao time! For the first time, China’s Gaokao essay topic was about the latest AI developments, triggering discussions on social media.

Published

2 months agoon

June 7, 2024

This week, China’s National College Entrance Exams, better known as the “Gaokao” (高考), became one of the most-discussed topics on Chinese social media. ‘Gaokao,’ ‘AI,’ and ‘Gaokao essay’ were the hottest words on Weibo by the end of the week.

The Gaokao (literally: ‘higher exams’) are a prerequisite for entering China’s higher education institutions and are usually taken by students in their last year of senior high school. June 7th marked the first day of the Gaokao, which will continue until June 9th.

For the over 13.4 million participating students, the Gaokao week is a pivotal moment. Scoring high on this exam can grant access to better colleges, significantly improving their chances of obtaining a good job after graduation. Given the potentially life-changing results, the Gaokao period is a stressful time for both students and their parents.

The Gaokao essay (高考作文) is a significant component of the Chinese language exam, testing students’ writing skills, critical thinking, and ability to express ideas coherently. The essay, which must be completed within a limited time, requires students to discuss given topics.

These topics are generally related to Chinese society and culture, consistently attracting attention on social media. This year, multiple essay questions were related to AI and social media.

Those taking the Beijing exam (北京卷), for example, received a question related to the “like” function on WeChat, suggesting that some people feel strongly about the number of “likes” they receive and give, asking students to reflect on the phenomenon of receiving and giving “likes” on social media.

But the question receiving the most attention on social media was part of the New Curriculum Standard Test I (新课标I卷), which is distributed among different provinces.

Students vs. Chatbots: Letting AI Write an Essay on AI

Students received the following topic prompt for their Gaokao essay, which should be at least 800 characters long:

“With the spread of the internet and AI applications, we can quickly get answers to more and more questions. Will this also lead to us having fewer problems?” (随着互联网的普及、人工智能的应用,越来越多的问题能很快得到答案。那么,我们的问题是否会越来越少?)

The question sparked discussions because it was the first time a Gaokao essay question focused on AI applications designed to interact with users, like ChatGPT.

Although many thought the essay question was easy—unlike this year’s math exam—it still generated some interesting reflections.

Some Weibo users responded that the answer to the question was within the question itself. One Weibo blogger answered: “If there were no AI, we wouldn’t have this question, so problems/questions related to AI will only increase. The emergence of new things will inevitably be accompanied by new problems.”

Others commented on the concerns brought by the emergence of AI applications like ChatGPT. In early 2023, hashtags such as “Ten Professions That Could be Replaced by ChatGPT” (#可能被ChatGPT取代的10大职业#) gained a lot of attention on Chinese social media, where many were concerned that jobs from various industries, including customer service, programming, media, education, market research, finance, etc., would soon be done by AI chatbots instead of humans.

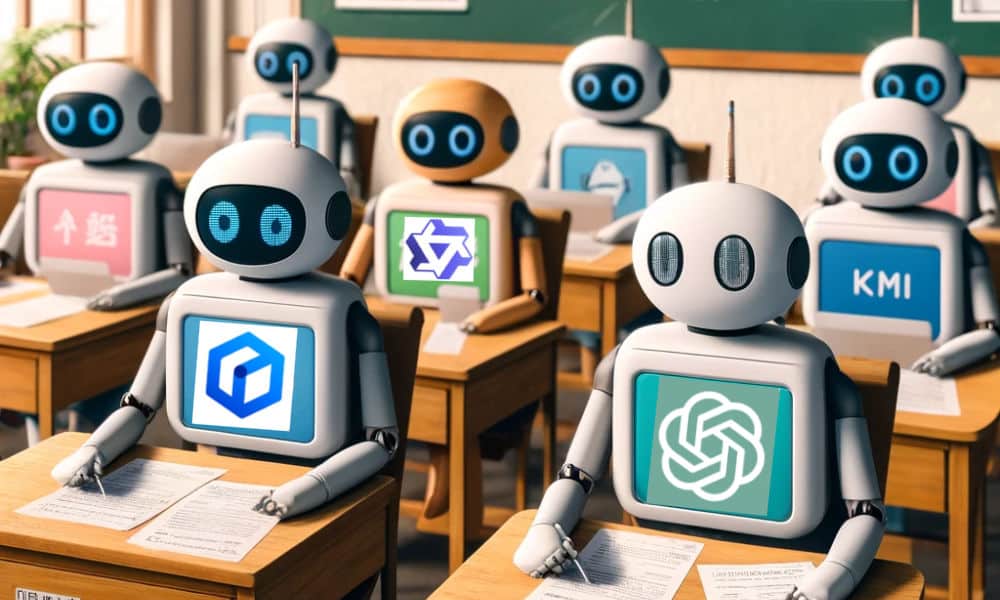

In line with this thought and the AI theme of this year’s Gaokao essay, netizens and some Chinese media outlets decided to let various language models take the exam and see how they would perform: could AI actually do better in writing an essay about AI than Chinese students? (Related hashtags: #让AI写高考作文#, #假如AI写高考语文作文#; #ChatGPT来交卷了#).

Xinhua, for example, asked Open AI’s ChatGPT to answer various questions. Sina Tech (新浪科技) also asked OpenAI’s ChatGPT to answer the AI-related essay question, along with Chinese chatbots, like Baidu’s Erniebot (文心一言), Tencent’s Yuanbao (元宝), iFlytek’s Sparkdesk (星火), and Alibaba’s Tongyi Qianwen (通义千问). Toutiao News did the same, letting three chatbots (ChatGPT, Erniebot, Tongyi Qianwen) compete against each other.

There is no general consensus on how well these AI chatbots can write a Gaokao essay. Although compared to last year, there are now more and better domestic AI models, OpenAI’s ChatGPT-4 is generally still seen as the best chatbot out there.

This was its answer (originally in Chinese, translated to English with ChatGPT):

New Issues and Thoughts Brought by Technological Progress

With the popularization of the internet and the application of artificial intelligence, we can quickly obtain a large amount of information, and many questions can be answered in a short time. However, does this mean that we will have fewer questions? I believe the answer is no.

Firstly, although technology provides us with convenience, new technologies also bring new problems. The popularization of the internet has made information dissemination faster, but at the same time, the authenticity and accuracy of information have become new concerns. Fake news, information overload, and privacy breaches are increasingly prominent issues. These new problems need to be identified, understood, and resolved by us.

Secondly, the application of artificial intelligence, although it improves efficiency, also brings ethical and social issues. The transparency of AI decision-making, algorithmic bias, and the impact on the job market are all urgent issues that society needs to address. People need to constantly raise new questions to ensure a balance between technological progress and social welfare.

Furthermore, the development of technology prompts us to reflect more deeply on humanity itself. We need to rethink the relationship between humans and technology and consider the role and boundaries of technology in our lives. These philosophical issues are more important than ever.

Therefore, technological progress does not reduce our questions but rather prompts more new questions and reflections. It is these constantly emerging questions that drive social progress and human thought. We need to embrace the challenges brought by technology with a more open and critical attitude and actively seek solutions.

Although the domestic chatbots gave somewhat different answers, the overall tone was similar, though some commenters argued that ChatGPT was still the strongest, along with iFlytek’s Sparkdesk.

An online poll asking Weibo users to grade the ChatGPT essay from lower than 20 points up to the full 60 points saw divided responses, though a majority rated it as lower than 20 points.

How well can ChatGPT write an essay about AI? Opinions are divided.

This shows that many commenters think that AI chatbots are still not able to beat humans when it comes to writing Gaokao essays.

Commenters reacted to the various AI-generated essays in various ways, including:

• “Actually, none of them are very good. They are too formulaic and standardized, lacking the natural creativity and originality that humans possess.”

• “They just give soulless standard answers.”

• “It’s all about ‘firstly,’ ‘secondly,’ ‘furthermore.'”

• “There are no examples, no points proven; it should be a low grade.”

• “It’s just too stiff.”

• “This is like reading reports, not essays.”

• “AI places more emphasis on logic, which aligns with the writing style of foreigners.”

• “There’s no feeling in these essays; there’s a certain kind of AI feeling to AI.”

Meanwhile, some bloggers are taking up the challenge and are publishing their own online essays in response to the Gaokao question.

Some of them are not worried that chatbots will take over their critical tasks: “AI will be AI. There’s no connection to the social realities, and it’s as cold as ice.”

“Their words might make sense, but they lack feeling.”

But for some discussing the topic, they have come to realize that they are already depending too much on digital tools and AI applications for their everyday tasks, writing: “I made an attempt to write an essay, but discovered I already forgot how to do it!” For them, the discussion itself is a wake-up call that writing an essay from scratch is a skill that requires practice and cannot be fully replaced by chatbots, making personal creativity essential to score points and avoid the ‘AI-fication’ of texts.

PS:

In his book China’s Millennials, Eric Fish describes the limits on Chinese students’ answers; taboo responses, such as those containing harsh criticisms of the Chinese government or society, could potentially lead to failure. Although the essay is purportedly meant to showcase the student’s creativity, it must adhere to the unwritten rules of what is socially acceptable.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?