Chinese TV Dramas

No ‘Novoland’: This Really Is a Tough Year for Chinese Costume Dramas

After the sudden cancellation of the much-anticipated ‘Novoland’ premiere, Chinese fantasy costume dramas are facing grim prospects.

Published

5 years agoon

First published

With 1,4 billion views on its Weibo page, the Chinese fantasy drama Novoland: Eagle Flag was one of the most-anticipated series of the year. This week, the show was suddenly canceled twenty minutes ahead of its premiere. The incident is indicative of recent tensions within China’s TV drama industry, where some costume dramas have apparently failed to win the support of official regulators.

Just a week ago, What’s on Weibo reported about the Chinese fantasy drama Novoland: Eagle Flag (九州缥缈录, Jiǔzhōu piāomiǎo lù) being one of the most anticipated TV dramas in China this summer. On June 3rd at 21:40 CST, however, just twenty minutes before the drama’s much-awaited premiere on Tencent, Youku, and Zhejiang TV, the show was suddenly canceled.

Novoland: Eagle Flag, which has been called China’s answer to Game of Thrones, is a costume drama that tells a story of war, conspiracy, love, and corruption in a fantasy universe called Novoland. It is based on a popular web fantasy novel series by Jiang Nan (江南), and produced by Linmon Pictures. Production costs reportedly were as high as RMB 500 million ($72 million).

Why was the show’s premiere suddenly canceled? The only reason given for it on June 3rd was that there was a ‘medium problem’ (“介质原因”).

China’s English-language state tabloid Global Times reported on June 4th that their official sources also did not know the reason for the withdrawal, although they did admit to having received an order from “higher level,” which would come from China’s National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA,国家广播电视总局).

In March of 2018, China’s State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT), the former top regulatory body overseeing television productions, was officially abolished and replaced by three different state administrations in the ideological sector.

The NRTA is responsible for media control on radio and TV, and falls directly under the State Council. It is led by Nie Chenxi (聂辰席), who is also the deputy director of the Publicity Department of the Communist Party of China. This appears indicative that the Party now has more direct influence over this industry, as also recently suggested by Global Policy Watch, SupChina, and Variety. Under the NRTA, the regulation and censorship of Chinese TV dramas are as strict, and arguably stricter, than under the SAPPRFT.

Costume dramas: not enough “spiritual guidance”?

The strict control of the NRTA over China’s TV industry is especially visible this year. As reported by CCTV News, China’s regulatory body started to severely crack down on the rising popularity of Chinese costume dramas (古装剧) in March of 2019.

Regulatory rules were supposedly issued for costume dramas with ‘themes’ (题材) such as martial arts, fantasy, history, mythology, or palace, stating that they should not air or were to be taken down from online video homepages. The strictest crackdown would allegedly last until July.

From early on in 2019, it was already rumored that Chinese costume dramas would face a tough year.

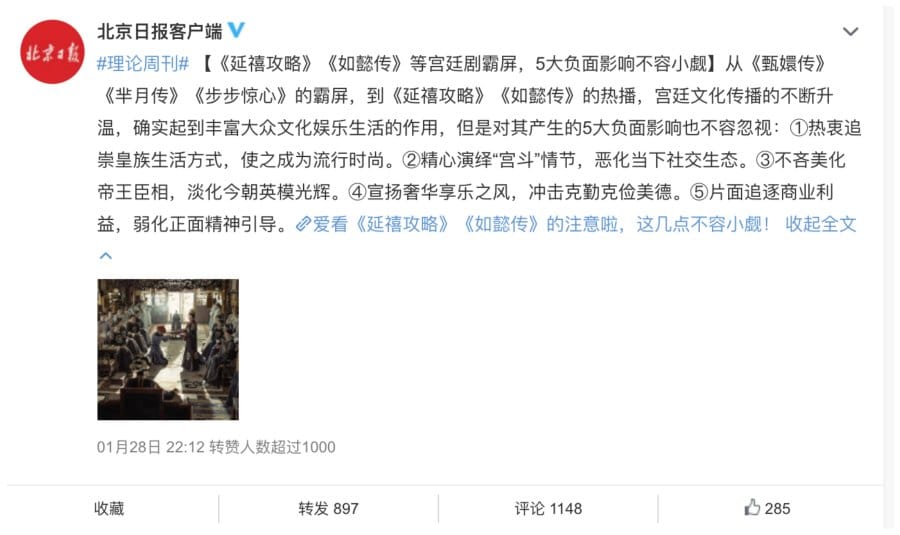

On January 28 of 2019, Beijing Daily, the official newspaper of the CPC Beijing Municipal Committee, published a critical post on its social media account listing negative influences of court-themed TV dramas (宫廷剧).

The critique included arguments such as that the imperial lifestyle was being hyped in these dramas, that the social situation of the dynastic era was being negatively dramatized, and that these productions are just aimed at commercial interests while weakening China’s “positive spiritual guidance.”

In February of this year, two weeks after the Beijing News post, Eduardo Baptista at CNN.com reported on the abrupt cancelation of the planned rebroadcasting of two costume dramas that were also targeted by Beijing News, namely the super TV drama hit Story of Yanxi Palace (延禧攻略) and period drama Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace (如懿传).

Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace

Other costume dramas such as iQiyi’s The Legend of White Snake (新白娘子传奇) or The Longest Day in Chang’an (长安十二时辰) were also withdrawn (or postponed) in March. Investiture of the Gods (封神) was replaced by another drama on Hunan TV this month.

“Historical dramas in many cases twisted the narrative of the country’s past and the image of historical figures,” TV critic Shi Wenxue was quoted by Global Times recently: “[they are] having an adverse effect on teenagers who may regard such fictional stories as real history.”

A state and marketplace collusion

With China being the world’s largest consumer of TV dramas in the world, the drama industry is a powerful channel for spreading Party ideology.

The political and cultural agenda is especially apparent in those TV dramas that are official propaganda productions. But since the TV drama industry has become increasingly commercialized and TV dramas became more market-oriented in the 1990s, their programming is no longer a mirror reflection of ‘Party narratives.’

The number of profit-driven productions has grown over the past 25 years and has skyrocketed with the arrival of video streaming sites such as iQiyi or Tencent Video.

Although non-official productions are ultimately still regulated and overseen by the relevant state departments, they also have to compete for viewer ratings in a highly competitive (online) media environment.

There are many visible trends in China’s TV drama industry. There have been peaks of popularity in those TV dramas depicting rural struggles or urban family life, for example, but historical costume dramas (especially dynasty dramas) have consistently been popular and rising since the mid-90s.

One reason for the growing popularity of these historical or fantasy costume dramas is that official censors initially had different standards for them than for more contemporary storylines, resulting in more creative freedom for scriptwriters (see Zhu et al 2008, 7).

Yongzheng’s Dynasty (1999)

There also have been many popular Chinese dynasty dramas that were commercial successes while also serving as propaganda tools.

As pointed out by Shenshen Cai in her work Television Drama in Contemporary China (2017), for example, TV drama serials such as Yongzheng Dynasty (雍正王朝) or The Great Han Emperor Wu (汉武大帝) promoted the ideal of strong central government, harmonious relations between the fatherly ruler and his devoted people, or the exemplary ruler cracking down on corruption – these narratives contributed to the leadership agenda in “stabilizing and re-energizing the dominant moral order” (Cai 3-4; also see Schneider 2012).

But more recent historical dramas have taken a fantasy route that, apparently, resonates with viewers but does not successfully appropriate the official propaganda apparatus.

The sudden withdrawal of new costume dramas is actually not about costume dramas at all. It just shows that although China’s TV drama industry is no longer the propaganda machine it once used to be, it still needs to adhere to those narratives that are in line with Party ideology.

‘Novoland: Eagle Flag’ (2019)

Even if their scripts and productions were apparently given the green light in earlier stages, the official supervision bodies still have the power to intervene until the last moment before airing – even if that, apparently, means that moment is twenty minutes ahead of the grand premiere.

“Things don’t look too optimistic”

For Chinese drama fans, the recent cancellations have been a real slap in the face. The Novoland: Eagle Flag TV serial was super popular before it even aired: its hashtag page has a staggering 1.4 billion views on Weibo.

“I cried,” one ‘Novoland’ fan comments: “Why such a sudden and abrupt withdrawal?”

“When can we finally see this show?” others wonder.

[Eng Sub] #Novoland: #EagleFlag director's edition – Dir. #ZhangXiaobo talks about his vision for the drama, his understanding of the three main characters (ft. #LiuHaoran, #SongZuer, and #ChenRuoxuan), the harsh conditions during filming, and more

Full – https://t.co/Jqa2z7LMEm pic.twitter.com/2RvsrMcsNW

— NOVOLAND: EAGLE FLAG (@eagleflag_intl) 3 juni 2019

For now, the show’s premiere has officially been “postponed” and is “waiting for specific broadcasting time.” Whether or not the 55-episode series will be allowed to broadcast after June is still to be seen.

On Twitter, the fan account of Liu Haoran (刘昊然), one of the show’s main stars, writes: “You’re going to see rumors of tentative dates flying around this week, but note that it’s more of a deadline to get things sorted, not an air date. As of right now, things don’t look too optimistic. We’ll just have to be patient!

More: For an overview of all of our articles on Chinese TV Dramas, please check this list.

By Manya Koetse

Follow @whatsonweibo

References

Cai, Shenshen. 2017. Television Drama in Contemporary China: Political, social and cultural phenomena. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Schneider, Florian. 2012. Visual Political Communication in Popular Chinese Television Series. Leiden and Boston: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Zhu, Ying, Michael Keane, Ruoyun Bai (eds). 2008. TV Drama in China. Hong Kong University Press.

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2019 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Arts & Entertainment

Going All In on Short Streaming: About China’s Online ‘Micro Drama’ Craze

For viewers, they’re the ultimate guilty pleasure. For producers, micro dramas mean big profit.

Published

4 months agoon

March 26, 2024By

Ruixin Zhang

PREMIUM CONTENT

Closely intertwined with the Chinese social media landscape and the fast-paced online entertainment scene, micro dramas have emerged as an immensely popular way to enjoy dramas in bite-sized portions. With their short-format style, these dramas have become big business, leading Chinese production studios to compete and rush to create the next ‘mini’ hit.

In February of this year, Chinese social media started flooding with various hashtags highlighting the huge commercial success of ‘online micro-short dramas’ (wǎngluò wēiduǎnjù 网络微短剧), also referred to as ‘micro drama’ or ‘short dramas’ (微短剧).

Stories ranged from “Micro drama screenwriters making over 100k yuan [$13.8k] monthly” to “Hengdian building earning 2.8 million yuan [$387.8k] rent from micro dramas within six months” and “Couple earns over 400 million [$55 million] in a month by making short dramas,” all reinforcing the same message: micro dramas mean big profits. (Respectively #短剧爆款编剧月入可超10万元#, #横店一栋楼半年靠短剧租金收入280万元#, #一对夫妇做短剧每月进账4亿多#.)

Micro dramas, taking China by storm and also gaining traction overseas, are basically super short streaming series, with each episode usually lasting no more than two minutes.

From Horizontal to Vertical

Online short dramas are closely tied to Chinese social media and have been around for about a decade, initially appearing on platforms like Youku and Tudou. However, the genre didn’t explode in popularity until 2020.

That year, China’s State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television (SARFT) introduced a “fast registration and filing module for online micro dramas” to their “Key Online Film and Television Drama Information Filing System.” Online dramas or films can only be broadcast after obtaining an “online filing number.”

Chinese streaming giants such as iQiyi, Tencent, and Youku then began releasing 10-15 minute horizontal short dramas in late 2020. Despite their shorter length and faster pace, they actually weren’t much different from regular TV dramas.

Soon after, short video social platforms like Douyin (TikTok) and Kuaishou joined the trend, launching their own short dramas with episodes only lasting around 3 minutes each.

Of course, Douyin wouldn’t miss out on this trend and actively contributed to boosting the genre. To better suit its interface, Douyin converted horizontal-screen dramas into vertical ones (竖屏短剧).

Then, in 2021, the so-called mini-program (小程序) short dramas emerged, condensing each episode to 1-2 minutes, often spanning over 100 episodes.

These short dramas are advertised on platforms like Douyin, and when users click, they are directed to mini-programs where they need to pay for further viewing. Besides direct payment revenue, micro dramas may also bring in revenue from advertising.

‘Losers’ Striking Back

You might wonder what could possibly unfold in a TV drama lasting just two minutes per episode.

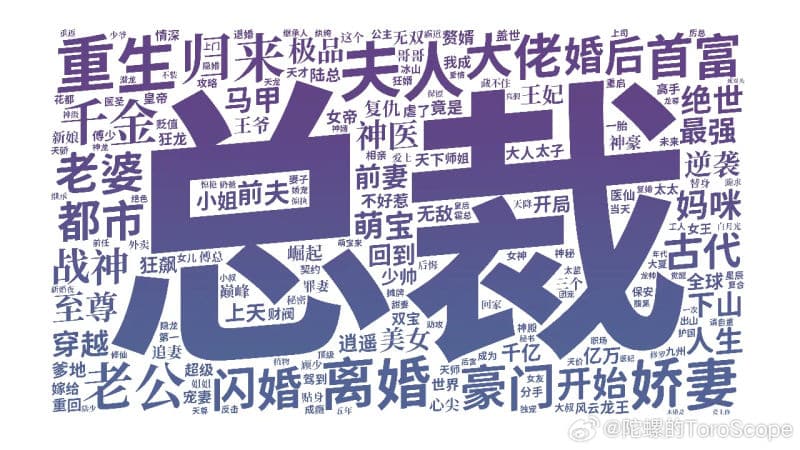

The Chinese cultural media outlet ‘Hedgehog Society’ (刺猬公社) collected data from nearly 6,000 short dramas and generated a word cloud based on their content keywords.

In works targeted at female audiences, the most common words revolve around (romantic) relationships, such as “madam” (夫人) and “CEO” (总裁). Unlike Chinese internet novels from over a decade ago, which often depicted perfect love and luxurious lifestyles, these short dramas offer a different perspective on married life and self-discovery.

According to Hedgehog Society’s data, the frequency of the term “divorce” (离婚) in short dramas is ten times higher than “married” (结婚) or “newlyweds” (新婚). Many of these dramas focus on how the female protagonist builds a better life after divorce and successfully stands up to her ex-husband or to those who once underestimated her — both physically and emotionally.

One of the wordclouds by 刺猬公社.

In male-oriented short dramas, the pursuit of power is a common theme, with phrases like “the strongest in history” (史上最强) and “war god” (战神) frequently mentioned. Another surprising theme is “matrilocal son” (赘婿), the son-in-law who lives with his wife’s family. In China, this term is derogatory, particularly referring to husbands with lower economic income and social status than their wives, which is considered embarrassing in traditional Chinese views. However, in these short dramas, the matrilocal son will employ various methods to earn the respect of his wife’s family and achieve significant success.

Although storylines differ, a recurring theme in these short dramas is protagonists wanting to turn their lives around. This desire for transformation is portrayed from various perspectives, whether it’s from the viewpoint of a wealthy, elite individual or from those with lower social status, such as divorced single women or matrilocal son-in-laws. This “feel-good” sentiment appears to resonate with many Chinese viewers.

Cultural influencer Lu Xuyu (@卢旭宁) quoted from a forum on short dramas, explaining the types of short dramas that are popular: Men seek success and admiration, and want to be pursued by beautiful women. Women seek romantic love or are still hoping the men around them finally wake up. One netizen commented more bluntly: “They are all about the counterattack of the losers (屌丝逆袭).”

The word used here is “diaosi,” a term used by Chinese netizens for many years to describe themselves as losers in a self-deprecating way to cope with the hardships of a competitive life, in which it has become increasingly difficult for Chinese youths to climb the social ladder.

Addicted to Micro Drama

By early 2024, the viewership of China’s micro dramas had soared to 120 million monthly active users, with the genre particularly resonating with lower-income individuals and the elderly in lower-tier markets.

However, short dramas also enjoy widespread popularity among many young people. According to data cited by Bilibili creator Caoxiaoling (@曹小灵比比叨), 64.9% of the audience falls within the 15-29 age group.

For these young viewers, short dramas offer rapid plot twists, meme-worthy dialogues, condensing the content of several episodes of a long drama into just one minute—stripping away everything except the pure “feel-good” sentiment, which seems rare in the contemporary online media environment. Micro dramas have become the ultimate ‘guilty pleasure.’

Various micro dramas, image by Sicomedia.

Even the renowned Chinese actress Ning Jing (@宁静) admitted to being hooked on short dramas. She confessed that while initially feeling “scammed” by the poor production and acting, she became increasingly addicted as she continued watching.

It’s easy to get hooked. Despite criticisms of low quality or shallowness, micro dramas are easy to digest, featuring clear storylines and characters. They don’t demand night-long binge sessions or investment in complex storylines. Instead, people can quickly watch multiple episodes while waiting for their bus or during a short break, satisfying their daily drama fix without investing too much time.

Chasing the gold rush

During the recent Spring Festival holiday, the Chinese box office didn’t witness significant growth compared to previous years. In the meantime, the micro drama “I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother” (我在八零年代当后妈), shot in just 10 days with a post-production cost of 80,000 yuan ($11,000), achieved a single-day revenue exceeding 2 million yuan ($277k). It’s about a college girl who time-travels back to the 1980s, reluctantly getting married to a divorced pig farm owner with kids, but unexpectedly falling in love.

Despite its simple production and clichéd plot, micro dramas like this are drawing in millions of viewers. The producer earned over 100 million yuan ($13 million) from this drama and another short one.

“I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother” (我在八零年代当后妈).

The popularity of short dramas, along with these significant profits, has attracted many people to join the short drama industry. According to some industry insiders, a short drama production team often involves hundreds or even thousands of contributors who help in writing scripts. These contributors include college students, unemployed individuals, and online writers — seemingly anyone can participate.

By now, Hengdian World Studios, the largest film and television shooting base in China, is already packed with crews filming short dramas. With many production teams facing a shortage of extras, reports have surfaced indicating significant increases in salaries, with retired civil workers even being enlisted as actors.

Despite the overwhelming success of some short dramas like “I Went Back to the 80s and Became a Stepmother,” it is not easy to replicate their formula. The screenwriter of the time-travel drama, Mi Meng (@咪蒙的微故事), is a renowned online writer who is very familiar with how to use online strategies to draw in more viewers. For many average creators, their short drama production journey is much more difficult and less fruitful.

But with low costs and potentially high returns, even if only one out of a hundred productions succeeds, it could be sufficient to recover the expenses of the others. This high-stakes, cutthroat competition poses a significant challenge for smaller players in the micro drama industry – although they actually fueled the genre’s growth.

As more scriptwriters and short dramas flood the market, leading to content becoming increasingly similar, the chances of making profits are likely to decrease. Many short drama platforms have yet to start generating net profits.

This situation has sparked concerns among netizens and critics regarding the future of short dramas. Given the genre’s success and intense competition, a transformation seems inevitable: only the shortest dramas that cater to the largest audiences will survive.

In the meantime, however, netizens are enjoying the hugely wide selection of micro dramas still available to them. One Weibo blogger, Renmin University Professor Ma Liang (@学者马亮), writes: “I spent some time researching short videos and watched quite a few. I must admit, once you start, you just can’t stop. ”

By Ruixin Zhang, edited with further input by Manya Koetse

Independently reporting China trends for over a decade. Like what we do? Support us and get the story behind the hashtag by subscribing:

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Brands, Marketing & Consumers

Show-Inspired Journeys: Chinese Netizens Explore Next Travel Destination Through Favorite TV Series

The rising influence of Chinese TV dramas on tourism highlights the synergy between entertainment & social media in China, serving as a powerful tool for travel promotion.

Published

7 months agoon

January 7, 2024

The Chinese TV series Meet Yourself has significantly boosted the popularity of Dali in Yunnan. The series’ success, coupled with the official funding behind it, not only underscores the impactful role of Chinese dramas in tourism but also illustrates how Chinese travel destination promotional strategies are being reshaped in a competitive post-Covid era.

On December 25th, the Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture’s Culture and Tourism Bureau in Yunnan Province, Southwest China, announced a proposed subsidy of 2 million yuan ($282k) for the Chinese TV series Meet Yourself (去有风的地方).

The news soon went trending on Weibo (#去有风的地方获200万元补助#). Many found it noteworthy, especially since the announcement clarified that this funding is part of the prefecture’s special fund for cultural and tourism industry development, and the TV series was the only project under consideration.

There are several reasons why Dali might consider this strategy.

Firstly, Dali plays a pivotal role in Meet Yourself. Launched in January 2023, the TV series quickly became an online sensation, achieving an impressive rating of 8.7 out of 10 on Douban—a platform in China similar to IMDb. Spanning 40 episodes, the series features actress Liu Yifei (刘亦菲), renowned for her role in Disney’s live-action Mulan, and Chinese actor Li Xian (李现).

Promotional image for Meet Yourself (去有风的地方).

The narrative follows a white-collar worker in her mid-30s who, following her best friend’s unexpected cancer diagnosis and subsequent passing, embarks on a quest to understand the true meaning and purpose of life.

The TV series not only captivated audiences because of its soothing narrative about life and interpersonal relationships, but the show was also a hit because most of its scenes were filmed in Dali and showed picturesque rural landscapes and portrayed a slow-paced, idyllic lifestyle.

The show accumulated more than 3 billion views on the streaming platform Mango TV by the time its final episode aired on February 2, 2023. It also sparked numerous trending topics on Weibo during that time. For instance, one snapshot from the drama, “Liu Yifei Holding Flowers” (刘亦菲捧花), also went viral, with many netizens even changing their profile pictures to this image. Captivated by Liu’s beauty and charm, they believed that the image possessed some sort of magical power, like the symbolic significance of koi fish in Chinese culture and how they’re believed to bring good luck.

The ‘lucky’ Liu Yifei holding flowers image.

The lucky Liu Yifei holding flowers meme spread across social media in various ways.

Benefiting directly from the popularity generated by the TV series, Yunnan experienced a surge in visitors during the 2023 Spring Festival holiday. This influx significantly boosted its tourism revenue to an impressive 38.4 billion yuan (approximately US$5.4 billion), surpassing all other provinces and regions in the country.

The primary filming location of the drama, the Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture, welcomed over 4.2 million visitors, marking a significant year-on-year increase. Within the first six days of the holiday, Dali boasted the highest room occupancy rate nationwide, and became the fifth most visited tourist destination across the country.

TV Series Inspiring Real-Life Travel to Featured Destination

Dali is not the only city or travel destination that has become popular because of Chinese dramas or TV shows. The recent Chinese TV series There Will Be Ample Time (故乡,别来无恙), in which Chengdu plays a major role, has also come to be seen as a promotion for the Sichuan Province capital city.

The series revolves around four women who grew up together, chose different paths in life, and then reconnect in Chengdu. The series showcases the city’s laid-back lifestyle, especially in contrast to the fast-paced metropolises like Beijing and Shanghai where the featured women return from.

Scene from There Will be Ample Time (故乡,别来无恙).

Back in 2003, the TV series Lost Time (似水年华), which was filmed in the historic scenic town of Wuzhen, also became popular. Lost Time was written, directed, and starred by the renowned Chinese actor and director Huang Lei (黄磊). The series narrates a poignant love story of a couple in their thirties who meet in Wuzhen, only to be separated by the vast distance between Wuzhen and Taipei.

The TV series successfully showcased the timeless beauty of the Wuzhen water town to a broader Chinese audience and, indirectly, promoted the town’s unique artistic and cultural atmosphere. This later led to the establishment of the Wuzhen Theatre Festival, a celebration of performing arts and a center for cultural exchange. The festival has since become one of the premier events in China and Asia. Each year, as the festival unfolds, there is a significant increase in business, with tourists flocking to the area.

On social media today, Lost Time is still seen as one of the major reasons why Wuzhen became so popular among Chinese travelers.

Wuzhen featured in Lost Time (似水年华).

But it’s not only the television series that portray a slower-paced and romantic lifestyle that motivate viewers to visit the showcased destinations. In 2020, the filming locations of the popular Chinese crime and suspense drama The Bad Kids (隐秘的角落) not only entertained its audience but also boosted tourism in the actual places where it was shot.

Much of the filming for the TV thriller took place in Chikan, an old township located in Zhanjiang in Guangdong. As a result, Zhanjiang’s popularity as a tourist destination skyrocketed by 261 percent in a single week.

Earlier in 2023, Jiangmen in Guangdong Province also gained popularity after it was featured in the popular crime TV drama The Knockout (狂飙). As a result, it became a sought-after destination during the May Day holiday, drawing numerous TV enthusiasts to the city. Jiangmen reportedly received over 765,200 visitors in the first two days of the May Day holiday alone, generating a revenue of approximately 439 million yuan (US$62.2 million).

Jiangmen’s popularity went beyond the May Day holiday. The Knockout caused a steady influx of visitors to the Guangdong city. From January to October of 2023, the city saw a total of 20,278,200 tourists, a reported year-on-year increase of 85.36%. This resulted in a tourism revenue of 19.649 billion yuan, representing an impressive increase of 133.77%.

Beyond the TV Screen: Social Media Creating Travel Hits

Over the past few years, we’ve seen how there are always unpredictable factors that help Chinese destinations suddenly become a hit among travelers. For instance, in late 2021, a song titled “Mohe Ballroom” (漠河舞厅) gained popularity across various social media platforms in China. This song narrates the story of a man who, for thirty years, danced alone in the Mohe Ballroom following the death of his beloved wife.

Prior to the song’s release, many Chinese netizens were familiar with Mohe as it is the northernmost point of China, and it is extremely cold. As the song gained traction on social media, the local government seized the opportunity to promote the city’s ice and snow tourism. Now, Mohe has emerged as a new destination for tourists seeking a unique, chilly experience.

Another example is Zibo, an ancient industrial city, which treated students well during their Covid quarantine period. So, when China lifted all Covid restrictions in the spring of 2023, these students returned to express their gratitude and celebrate the city. Their contagious enthusiasm, coupled with their social media posts about the city, sparked nationwide interest and people soon flocked to Zibo to enjoy the vibe and the local BBQ (read more here).

During the summer of 2023, the city of Tianjin became online hit due to a group of energetic seniors who transformed a local bridge into a stage for their remarkable water acrobatics. Tianjin’s so-called “diving grandpas” attracted attention for their daring dives into the river from the Stone Lion Forest Bridge (狮子林桥). Videos of their dives quickly went viral on China’s social media, drawing tourists, including many foreign residents in China, to witness the spectacle firsthand. Some people even joined to dive, including He Chong (何冲), the 2008 Olympic Champion in the 3m springboard.

Tianjin’s diving grandpas had to stop their diving activities after rising to internet fame, causing too many people to dive into the river.

In a playful twist, some visitors created their own scorecards, acting as judges and rating the divers’ performances. However, this spontaneous event eventually had to be toned down due to safety concerns. Despite this, the event kept Tianjin in the spotlight for quite a while as a tourist destination.

Social media has become a vital tool for cities and tourist destinations aiming to attract potential visitors. While some destinations organically become online sensations due to a combination of factors, other efforts are more deliberate and strategic. For instance, in spring of 2023, Chinese local government officials went all out to promote their hometowns via online channels, going viral on Weibo, Douyin, and beyond for dressing up in traditional outfits and creating original videos about their hometowns with low to zero budget.

However, when an article by Xinhua News criticized this approach, suggesting that local officials should prioritize improving service quality in their hometowns rather than striving for internet fame, the online trend appeared to wane.

Over the last year, different regions and industries in China made significant efforts to boost their local economies through tourism to recover from the impact of the pandemic. The China Tourism Academy recently published a report that forecasts that the number of China’s domestic tourists in 2023 has hit 5.407 billion, and domestic tourism revenue will amount to 5.2 trillion yuan. This figure allegedly represents a recovery to 90% compared to pre-Covid year 2019.

The upcoming Chinese New Year’s holiday is expected to kick off a promising start for the Chinese tourism industry in 2024. According to Trip.com data, bookings for the 2024 New Year’s holiday have surged by over threefold compared to the corresponding period last year. Furthermore, Tongcheng Travel highlights skiing, hot springs, Northern Lights viewing, music events, outdoor activities, island retreats, cruises, staycations, and firework displays as the top domestic travel preferences during this holiday season.

As China has significantly relaxed several travel and visa policies for both Chinese and international travelers, the number of outbound travel bookings for the New Year’s holiday on Trip.com has also seen a nearly fivefold increase compared to the same period last year while inbound tourism is on the rise.

Meanwhile, the way in which the TV drama Meet Yourself (去有风的地方) has boosted the tourism industry of Dali, which already was a popular tourist destination, is generating ongoing discussions on Chinese social media as it is a good example of how the integration of destination themes can captivate viewers’ attention, inspiring them to visit and discover the real-life locations.

In this way, TV shows serve as powerful platforms for local tourism authorities across China. First, utilizing television series provides them with a higher level of control compared to other methods of online promotion, including more fleeting trends. The show’s narratives, vibe, and filming locations can precisely showcase a destination’s unique features, attractions, and local culture.

Second, featuring destinations in TV series effectively accomplishes two goals at once, as Chinese TV dramas and online communities have become strongly intertwined. This amplifies the influence and reach of such productions, as fans engage, share, discuss, and promote the series and associated destinations across various social media platforms. And so, a featured scene or image, such as the one with Liu Yifei, can transcend the series itself and become an entire trend of its own on Chinese social media channels.

For travelers, visiting a destination featured in a beloved TV drama is not just about exploring a new location—it’s about experiencing a feeling and and immersing oneself in a fantasy. This trend won’t end with Meet Yourself, as new dramas inspire viewers to visit new locations again. As fans are binge watching the TV series Love Me, Love My Voice (很想很想你), Guangxi’s Guilin is the next hotspot attracting attention online for its portrayal in the show. “I finished watching the show,” one viewer wrote, “Now I want to start traveling.”

By Wendy Huang

Follow @whatsonweibo

Edited for clarity by Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. Please note that your comment below will need to be manually approved if you’re a first-time poster here.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?