Featured

Pressured to get Married: For the Country and For Society

Every year, China’s bachelors and bachelorettes are dreading the return to their hometowns, as parents and family members will inescapably ask them that one question: “Why are you not married yet?”

Published

9 years agoon

WHAT’S ON WEIBO ARCHIVE | PREMIUM CONTENT ARTICLE

A creative protest against social marriage pressure has reignited online discussions about the status quo of China’s unmarried adults. While some support the choice of Chinese younger adults to be in charge of their own happiness, others suggest they are too focused on personal fulfillment.

Chinese New Year and the pressure to get married: it has already become an ‘old’ topic. Every year, China’s bachelors and bachelorettes are dreading the return to their hometowns, as parents and family members will inescapably ask them that one question: “Why are you not married yet?”

This year, a group of Chinese young women protested in Shanghai against their parents pressuring them to marry, holding signs saying: “Mum, please do not force me to get married during New Year, I’m in charge of my own happiness.”

Protest in Shanghai against marriage pressure, February 4, 2015 (Qingdao News).

Protest in Shanghai against marriage pressure, February 4, 2015 (Qingdao News).

The women became a hot topic amongst netizens and authors, reigniting the online discussion about the status quo of China’s unmarried adults. “Coming back to your hometown saying you don’t want to be pressured into marriage is like going to the dog meat festival saying you don’t want to eat dog,” says writer Mao Li.

The Shengnü and Shengnan ‘problem’

The term ‘shengnü’ (剩女 ‘leftover woman’) has been a somewhat derogatory catch phrase in China’s media for years. It refers to women who are still single at the age of 27 or above; usually well-educated ladies who have difficulties in finding a partner that can live up to their expectations.

Their disadvantage in finding a partner relates to existing ideas in Chinese culture about the ‘ideal’ marriage age of women. A recent survey has pointed out that 50% of Chinese men already consider a women ‘left over’ when she is not married at the age of 25.

The male counterpart of the shengnü is the so-called ‘shengnan’ (剩男, ‘leftover man’). Chinese men face great difficulties in finding a bride, as Mainland China has been faced with an unbalanced male-female ratio since the 1980s. At the peak of disparity in 2004, more than 121 boys were born for every 100 girls. One explanation for this imbalance is the traditional preference for boys and sex-selective abortions since the one-child policy was introduced in 1978.

According to estimations, there currently are 20 million more men than women under the age of 30 (Luo & Sun 2014, 5; Chen 2011, 2).

The abundance of both single women and men in present-day China would suggest that there is hardly a problem: why don’t they just get married? Problematically, the majority of China’s unmarried women are twenty-somethings who live in urban areas and are at the ‘high end’ of the societal ladder (relatively high income and education), whereas the majority of the shengnan are based in rural areas and are at the ‘lower end’ (lower income/education).

Since Chinese women traditionally prefer to ‘marry up’ in terms of age, income and education, and the men usually ‘marry down’, the men and women find themselves at the wrong ends of the ladder (Ding & Xu 2015, 114).

China needs a babyboom

“Get married soon and have lots of babies,” says Huang Wenzheng, activist and one-child policy opponent (Qi 2014). China is currently facing a rapid decline in births. At the same time, the population is aging.

It is estimated that over 25% of Chinese people will be 65 years and older in 2050, leaving the burden of care to younger generations (BBC 2012). Getting Chinese bachelors and bachelorettes to marry and produce children has thus gone beyond the wish for a wedding banquet and cute grandchildren – it has become an important matter to society.

According to recent statistics, 80% of China’s bachelors and bachelorettes over the age of 24 experience pressure by their families to get married when they go home for the holiday period. The festival is now even nicknamed the “marriage pressure holiday” (催婚假期).

Parents looking for a suitable partner for their single sons and daughter (Xinhua).

Parents looking for a suitable partner for their single sons and daughter (Xinhua).

After Chinese New Year, there generally is a 40% increase in blind dates. These meetings are often arranged by the parents, who attend ‘blind date events’ for their single sons or daughters. Many parents gather in public parks over the weekend, carrying banners with the picture and details of their unmarried child in the hopes of finding a suitable marriage partner for them.

“Don’t oppose to marriage pressure if you’re a loser”

Well-known scholar Yang Zao (杨早) responds to this topic on Tencent’s Dajia (‘Everybody’, a media platform for authors), with an essay titled “Pressured to Get Married: For the Country, For Society” (为了国家,为了社会,逼你结婚). Yang is the third author to discuss the New Year’s marriage pressure and the Shanghai girls who want to take their love life into their own hands. The other two columns are by female writer Mao Li (毛利), who wrote an essay titled “Prove You’re Not a Loser Before Opposing Marriage Pressure” (想反逼婚,先证明你不是废物), and columnist Zhang Shi (张石), whose piece is called “China’s ‘Pressured-Married’ and Japan’s ‘Non-Married””(中国的“逼婚”和日本的“不婚”). Yang analyses the current debate on marriage, wondering if it is so controversial because society is pressuring it more or because unmarried adults are opposing it more.

Parents put more pressure on their children to get married, and children increasingly oppose it, says Mao Li. According to her, both sides make sense, but it is the children who have to explain their point-of-view; why would their parents understand them?

Those who were born in the 1980s and 1990s come from completely different times than their mothers and fathers, who suffered many hardships to get where they are today. Mao Li compares the way they raised their children to a farmer raising his crops: planting seeds, watering the fields and creating the right environment to grow. Now that the children are grown up and have left the family home, the logical step for them would be to get married – after all, their parents worked hard to build the right conditions for them to do so. They should not be surprised when their parents urge them to get settled.

“Coming back to your hometown saying you oppose to marriage pressure is like coming to the dog meat festival saying you oppose to eating dog,” Mao says: “You can’t expect people to comprehend it.” According to Mao, children can only oppose marriage pressure when they are completely independent. They cannot oppose marriage and still cling to their parents for financial support. “Prove you’re not a loser before opposing marriage pressure,” she says.

Writer Zhang Shi approaches the issue from another perspective; that of society. In Japan, fertility rates have sharply decreased. While society is ageing, the lack of young workers causes economic problems.

In order not to end up with the same problems as Japan, China has to get the marriages coming and birth rates going, argues Zhang. Parents who are forcing their children to get married are actually contributing to society, says Zhang: it is ‘warm advice’, not cold pressure. In an age of declining birthrates, urging people to have babies is a “social responsibility”.

“For the country, for society, for parents, can’t you let go a bit of ‘personal happiness’?”

The pressure to get married is ingrained in social ideology and China’s traditional family ethics, says Yang Zao. The problems that now emerge within society come from a clash between individualist and collectivist values.

Chinese society cannot be a perfect mix of both individualism and collectivism, according to Yang: “It is either one, and both will have downsides.” If China wants a liberal, individual-focused society, then its “evils” will have to be accepted too: some people will marry late, some will not marry at all, some will not have kids, others will go job-hopping, some people move from city to city and never settle down. Such a society will also generate low birth rates and an ageing society.

In a collective, family-focused society, the aging crisis and declining birth rates could be halted. Parents would not have to go to public parks to search for suitable partners for their unmarried kids. “For the country, for society, for parents, can’t you let go a bit of personal happiness’?”, says Yang. After all, isn’t marriage key to solving China’s present-day problems?

Since 1950, marriage officially is a ‘freedom of choice’ in Mainland China. Nevertheless, marriage in China still seems to involve more than two people: it is a get-together of two families with societal backing.

One Weibo user says: “The shengnü do not have an individual problem; they are a problem because society at large believes they have a problem – this is why it is a ‘problem’.”

No matter what the ‘nation’, ‘society’, or parents think, the protesting Shanghai girls are positive about their future: it is in their hands, and in their hands alone.

– by Manya Koetse

References

BBC. 2012. “Ageing China: Changes and Challenges.” BBC News, 19 September http://www.bbc.com/news/world-

Chen, Zhou. 2011. “The Embodiment of Transforming Gender and Class: Shengnü and Their Media Representations in Contemporary China.” Master’s thesis, University of Kansas.

Ding, Min and Jie Xu. 2015. The Chinese Way. Routledge: New York.

Luo, Wei, and Zhen Sun. 2014. “Are You the One? China’s TV Dating Shows and the Sheng Nü’s Predicament.” Feminist Media Studies, October: 1–18.

Mao Li 毛利. “想反逼婚,先证明你不是废物” [Prove You’re Not a Loser Before Opposing Marriage Pressure]. Dajia, 11 February http://dajia.qq.com/blog/466362096792665 [24.2.15].

Qi, 2014. “Baby Boom or Economy Bust.” The Wall Street Journal, 2 September http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2014/09/02/baby-boom-or-economy-bust-stern-warnings-about-chinas-falling-fertility-rate/ [24.2.15].

Yang Zao 杨早. 2015. “为了国家,为了社会,逼你结婚” [Pressured to Get Married: For the Country, For Society]. Dajia, 17 February http://dajia.qq.com/blog/431261063359665 [24.2.15].

Zhang Shi 张石. 2015. “中国的“逼婚”和日本的“不婚” [China’s ‘Pressured-Married’ and Japan’s ‘Non-Married’]. Dajia, 16 February http://dajia.qq.com/blog/462372023502987 [24.2.15].

Image by Tencent Dajia, 2015.

©2014 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Manya Koetse is the founder and editor-in-chief of whatsonweibo.com. She is a writer, public speaker, and researcher (Sinologist, MPhil) on social trends, digital developments, and new media in an ever-changing China, with a focus on Chinese society, pop culture, and gender issues. She shares her love for hotpot on hotpotambassador.com. Contact at manya@whatsonweibo.com, or follow on Twitter.

Also Read

China Memes & Viral

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Throughout the years, Biden has received many nicknames on Chinese social media.

Published

5 days agoon

July 22, 2024

Our Weibo phrase of the week is Bye Bye Biden (bài bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登). As news of Biden dropping out of the presidential race went viral on Weibo early Monday local time, it’s time to reflect on some of the popular nicknames and phrases given to US President Joe Biden on Chinese social media.

🔹 Biden in Chinese: Bàidēng 拜登

Biden in Chinese is generally written pronounced and written as Bàidēng 拜登. Although the character 拜 (bài) means “to pay respect, to worship” and 登 (dēng) means “to ascend, to climb,” they’re used here primarily for their phonetic similarity. The characters chosen are neutral to avoid any negative implications in the official translation of Biden’s name.

Why are non-Chinese names translated into Chinese at all? With English and Chinese being vastly different languages with entirely different phonetics and scripts, most Chinese people find it difficult to pronounce a foreign name written in English. Writing foreign names in Chinese not only standardizes them but also makes pronunciation and memorization easier for Chinese speakers.

🔹 Bye Biden: Bài Bài Bàidēng 拜拜拜登

Because Biden is Bàidēng, and the Chinese for ‘bye bye’ is written as bài bài 拜拜, some netizens quickly created the wordplay “bài bài Bàidēng” 拜拜拜登 (“bye bye Biden”) upon hearing that Biden would not seek reelection. Try saying it out loud—it almost sounds like you’re stammering.

🔹 Old Joe: Lǎo Dēng Dēng 老登登

Another common farewell greeting to Biden seen online is “bài bài lǎo dēng dēng” 拜拜老登登, which sounds cute due to the repetition of sounds.

“Old Biden” or “lǎo dēng dēng” 老登登 is a common online nickname for Biden in Chinese. The reduplication of the 登 (dēng) makes it sound playful and affectionate, while the “old” prefix is commonly used when referring to someone older. It’s similar to calling someone “Old Joe” in English.

🔹 Biden Variations: 拜灯, 白等, 败蹬

Let’s look at some other ways Biden is nicknamed online:

Besides the official way of writing Biden with the 拜登 Bàidēng characters, there are also other variations:

拜灯: bài dēng

白等: bái děng

败蹬: bài dèng

These alternative ways of writing Biden’s name are not neutral. Although the first variation is not necessarily negative (using the formal Biden 拜 bài character but with ‘Light’ 灯 dēng instead of the other 登 ‘dēng’), the other two variations are usually used in more negative contexts.

In 白等 (bái děng), the first character 白 (bái) means “white,” which can evoke associations with old age due to white hair (白发). The character 等 (děng) means “to wait,” and the combination can imply being old and sluggish.

败蹬 (bài dèng) is typically used by netizens to reflect negative sentiments towards the American president. The characters separately mean 败 (bài): “to be defeated,” “to fail,” and 蹬 (dèng): “to step on,” “to kick.” This would never be used by official media and is also often used by netizens to circumvent censorship around a Biden-related topic.

🔹 Revive the Country Biden: Bài Zhènhuá 拜振华

Then there is 拜振华 Bài Zhènhuá: revive the country Biden

In recent years, Biden has come to be referred to with the Chinese nickname “Revive the Country Biden,” also translatable as ‘Thriving China Biden’. This nickname has circulated online since 2020 and matches one previously given to former President Trump, namely “Build the Country Trump” (Chuān Jiànguó 川建国).

The idea behind these humorous monikers is that both Trump and Biden are seen as benefitting China by doing a poor job in running the United States and dealing with China.

🔹 Sleepy King: Shuì wáng 睡王

Shuì wáng 睡王, Sleepy King, is another common nickname, similar to the English “Sleepy Joe.” During and after the 2020 American presidential elections, there were numerous discussions on Chinese social media about ‘Trump versus Biden.’ Many saw it as a contest between the ‘King of Knowing’ (懂王) and the ‘Sleepy King’ (睡王).

These nicknames were attributed to Trump, who frequently boasted about his unparalleled understanding of various matters, and Biden, who gained notoriety for being older and tired. Viral videos, some manipulated, showed him nodding off or seemingly disoriented. The name ‘Sleepy King’ then stuck.

🔹 Grandpa Biden: Bài Yéyé 拜爷爷

Throughout the years, Biden has also been nicknamed Bài yéyé 拜爷爷, “Grandpa Biden.” This is usually more affectionate, though it emphasizes his age—Trump is not much younger than Biden and is not nicknamed ‘Grandpa Trump.’

Another similar nickname is lǎo bái 老白, “Old White,” referring to Biden’s age and white hair. 白 (bái, white) can also be a surname in Chinese. This nickname makes it seem like Biden is an old, familiar friend.

On Weibo, many speculate that American Vice President Kamala Harris will be the new candidate for the Democrats, especially since she’s been endorsed by Biden. Many have little confidence that she can compete against Trump. Her Chinese name is Kǎmǎlā Hālǐsī 卡玛拉·哈里斯, commonly referred to as ‘Harris’ (Hālǐsī).

In light of the latest developments, some netizens jokingly write: “Bye bye Biden, Ha ha ha, Harris.” (Bài bài, Bàidēng. Hā hā hā, Hālǐsī 拜拜,拜登。 哈哈哈,哈里斯). With a new Democratic candidate entering the presidential race, we can expect a fresh batch of creative nicknames to join the mix on Chinese social media.

Want to read more? Also read: Why Trump has Two Different Names in Chinese.

By Manya Koetse

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

China Memes & Viral

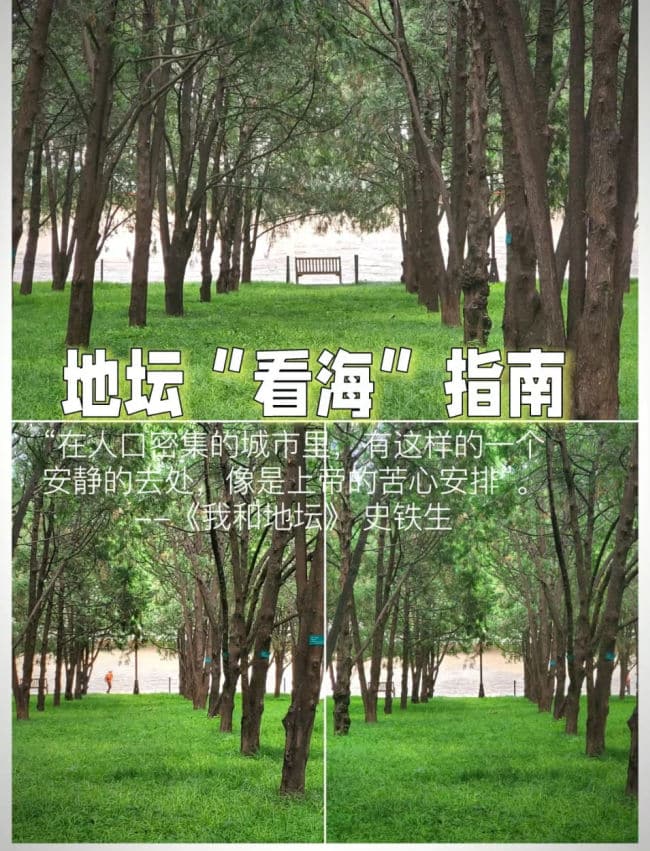

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

This “seaview” spot in Beijing’s Ditan Park has become a new ‘check-in spot’ among Chinese Xiaohongshu users and influencers.

Published

2 weeks agoon

July 15, 2024

“‘The sea in Ditan Park’ is a perfect example of how Xiaohongshu netizens use their imagination to change the world,” a recent viral post on Weibo said (“地坛的海”完全可以入选《红薯人用想象力颠覆世界》的案例合集了”).

The post included screenshots of the Xiaohongshu app where users share their snaps of the supposed seaview in Beijing’s Ditan Park (地坛公园).

Ditan, the Temple of Earth Park, is one of the city’s biggest public parks with tree-lined paths and green gardens in Beijing, not too far from the Lama Temple in Dongcheng District, within the Second Ring Road.

On lifestyle and social media platform Xiaohongshu, users have recently been sharing tips on where and how to get the best seaview in the park, finding a moment of tranquility in the hustle and bustle of Beijing city life.

Post on Xiaohongshu to get the seaview in Ditan Park.

But there is something peculiar about this trend. There is no sea in Ditan Park, nor anywhere else in Beijing, for that matter, as the city is located inland.

The ‘seaview’ trend comes from the view of one of the park’s stone walls. In the late afternoon, somewhere around 16pm, when the sun is not too bright, the light creates an optical illusion from a certain viewpoint in the park, making the wall behind the bench look like water.

You do have to capture the right light at the right moment, or else the effect is non-existent.

Some photos taken at other times of the day clearly show the brick wall, which actually doesn’t look like a sea at all.

Although the ‘seaview in Ditan’ trend is popular among many Xiaohongshu users and influencers who flock to the spot to get that perfect picture, there are also some social media commenters who criticize the trend of netizens always looking for the next “check-in spot” (打卡点).

There are also other spots popular on social media that look like impressive areas but are actually just optical illusions. Here are some examples:

One Weibo user suggested that this trend is actually not about people appreciating the beauty around them, but more about chasing the next social media hype.

The Ditan seaview trend is not entirely new. In May of this year, Beijing government already published a post about the “sea” in Ditan becoming more popular among social media users who especially came to the park for the special spot.

The Beijing Tourism Bureau previously referred to the spot as “the sea at Ditan Park that even Shi Tiesheng didn’t discover” (#在地坛拍到了史铁生都没发现的海#).

Shi Tiesheng (1951–2010) is a famous Chinese author from Beijing whose most well-known work, “Me and Ditan,” reflects on his experiences and contemplations in Ditan Park. At the age of 21, Shi Tiesheng suffered a spinal cord injury that left him paralyzed from the waist down. Ditan Park became a place for him to ponder life, time, and nature. Despite the author’s deep connection with the park, he never described seeing a “sea” in the walls.

Shi Tiesheng in Ditan Park.

If you are visiting Ditan Park and would like to check out the ‘sea’ yourself in the late afternoon, there are guides on Xiaohongshu explaining the route to the viewpoint. But it should not be too difficult to find this summer—just follow the crowds.

By Manya Koetse and Ruixin Zhang

Spotted a mistake or want to add something? Please let us know in comments below or email us. First-time commenters, please be patient – we will have to manually approve your comment before it appears.

©2024 Whatsonweibo. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce our content without permission – you can contact us at info@whatsonweibo.com.

Subscribe

Weibo Watch: The Future is Here

“Bye Bye Biden”: Biden’s Many Nicknames in Chinese

Enjoying the ‘Sea’ in Beijing’s Ditan Park

A Triumph for “Comrade Trump”: Chinese Social Media Reactions to Trump Rally Shooting

Weibo Watch: Get Up, Stand Up

The Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

“Old Bull Eating Young Grass”: 86-Year-Old Chinese Painter Fan Zeng Marries 36-Year-Old Xu Meng

A Brew of Controversy: Lu Xun and LELECHA’s ‘Smoky’ Oolong Tea

Singing Competition or Patriotic Fight? Hunan TV’s ‘Singer 2024’ Stirs Nationalistic Sentiments

Zara Dress Goes Viral in China for Resemblance to Haidilao Apron

Weibo Watch: The Battle for the Bottom Bed

About the “AI Chatbot Based on Xi Jinping” Story

China’s Intensified Social Media Propaganda: “Taiwan Must Return to Motherland”

Weibo Watch: Telling China’s Stories Wrong

Saying Goodbye to “Uncle Wang”: Wang Wenbin Becomes Chinese Ambassador to Cambodia

Get in touch

Would you like to become a contributor, or do you have any tips or suggestions? Get in touch here!

Popular Reads

-

China Insight3 months ago

China Insight3 months agoThe Tragic Story of “Fat Cat”: How a Chinese Gamer’s Suicide Went Viral

-

China Music4 months ago

China Music4 months agoThe Chinese Viral TikTok Song Explained (No, It’s Not About Samsung)

-

China Digital10 months ago

China Digital10 months agoToo Sexy for Weibo? Online Discussions on the Concept of ‘Cābiān’

-

China Arts & Entertainment12 months ago

China Arts & Entertainment12 months agoBehind 8 Billion Streams: Who is Dao Lang Cursing in the Chinese Hit Song ‘Luocha Kingdom’?